Abstract

The human soluble Guanylate Cyclase (hsGC) is a heterodimeric heme-containing enzyme which regulates many important physiological processes. In eukaryotes, hsGC is the only known receptor for nitric oxide (NO) signaling. Improper NO signaling results in various disease conditions such as neurodegeneration, hypertension, stroke and erectile dysfunction. To understand the mechanisms of these diseases, structure determination of the hsGC dimer complex is crucial. However, so far all the attempts for the experimental structure determination of the protein were unsuccessful. The current study explores the possibility to model the quaternary structure of hsGC using a hybrid approach that combines state-of-the-art protein structure prediction tools with cryo-EM experimental data. The resultant 3D model shows close consistency with structural and functional insights extracted from biochemistry experiment data. Overall, the atomic-level complex structure determination of hsGC helps to unveil the inter-domain communication upon NO binding, which should be of important usefulness for elucidating the biological function of this important enzyme and for developing new treatments against the hsGC associated human diseases.

Keywords: Homology modeling, Single/Multiple-chain threading, Protein-protein docking, Multi-domain assembly, Cryo-EM density map fitting

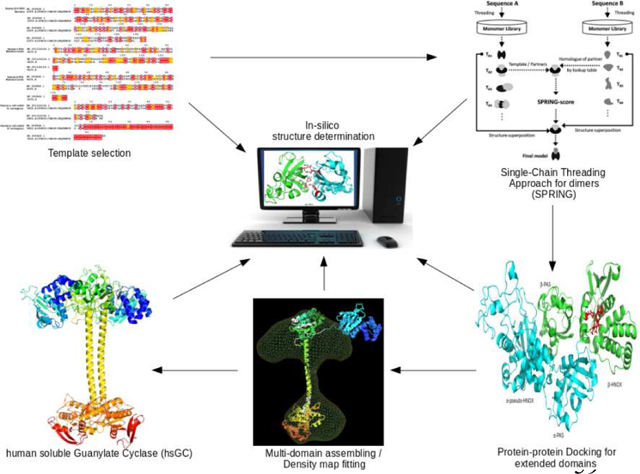

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The human soluble guanylate cyclase (hsGC) regulates multiple physiological processes such as neurotransmission, platelet aggregation, erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases [1][2]. In 1980s, NO was identified as the primary signaling molecule in NO signaling pathway that binds with the heme component of hsGC to generate 3’, 5’cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) from guanosine triphosphate (GTP). Subsequently, cGMP elicits the activation of multiple downstream proteins such as ion-gated channels, cGMP dependent protein kinases, and phosphodiesterase (PDE) [3][4][5].

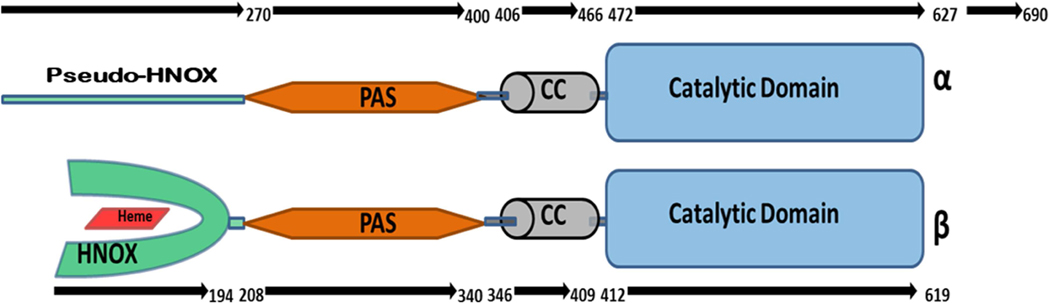

The sGC is a heterodimer of two subunits named α and β (Fig. 1). Each subunit is composed of four significant modular domains. The β subunit is able to bind NO and oxygen molecules through interactions established with a conserved structural motif found at the N-terminal and known as the heme-NO binding (HNOX) domain. The corresponding domain of the α subunit, the so called pseudo-HNOX domain, is deficit of heme and its role in the body is still elusive [6]. In both subunits the HNOX domain is followed by the PAS (Per/Arnt/Sim) and coiled-coil helical domains. These two domains have significant roles in NO induced hetero-dimerization and signal transduction to make a functional sGC [7][8]. The C-terminal of each subunit is composed of a cyclase domain which is responsible for production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) [9].

Fig. 1:

Domain architecture of Soluble Guanylate Cyclase (sGC) heterodimer. It consists of two subunits, α and β. Both subunits contains a PAS domain, a coiled-coil domain CC and a C-terminal cyclase (catalytic domain). The N-terminal of the α subunit has pseudo-HNOX domain while β subunit contains a heme-binding domain called HNOX. Length of each subunit and domain boundaries are also mentioned on the upper and lower arrows.

The structural information which is available for the, multi-domain organization of hsGC is limited because it is difficult to express and purify this protein target in prokaryotic or eukaryotic expression systems [10]. Crystal structure of inactive cyclase domain is the only known structure of hsGC.

Although little is known for the structure of human sGC, individual sGC domains from other species have determined structures. For example, structures of Nostoc punctiforme HNOX domain (PDB ID: 2O09) [11], Manduca sexta PAS domain (PDB ID: 4GJ4) [12] and Rattus norvegicus coil coiled domain (PDB id: 3HLS) [13] are available in Protein Data Bank (PDB). Data from biochemical and biophysical studies i.e. hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), chemical cross-linking and single-particle EM have revealed various structural aspects pertaining to multi-domain assembly of bacterial and R. norvegicus sGC [14][15]. Moreover, an intact cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) map of R. norvegicus sGC is also available which provides significant structural information about the putative domain orientation and quaternary structural packing of the sGC complex [16]. Based on structural organization of available homolog proteins and R. norvegicus sGC cryo-EM map information, we assume here that hsGC will attain similar structural organization of multiple domains in its quaternary structure.

Protein structures determined in high resolution by X-ray crystallography and NMR techniques provide wealth of structural information on intra-domain and inter-domain protein interactions of small sized proteins. In addition,, cryo-EM often provides low resolution structures of multi-component protein complexes which lack the intricate details of protein interactions involved in the cross talk of adjacent domains [18]. Despite the great advances in experimental methods of protein structure determination, the characterization of multi-domain protein complexes remains a challenging and often unreachable task [17].

Unavailability of a comprehensive sGC holoenzyme structure makes it difficult to elucidate the domain interactions and activation mechanism of the protein. The current study aims to determine the entire structure of hsGCαβ complex using computational protein structure modelling approaches. We applied knowledge based integrative protein structure modelling approach in which we utilized already reported experimental information that is available through X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM studies of hsGC homologs to predict full length multi-domain hsGCαβ heterodimer. Conserved orientations of adjacent domain partners in our query structure were predicted through template based (single or multiple chain threading) and template free (docking) methods. Biochemical constraints such as interaction residues at interface of neighboring domains were used as a benchmark to confirm their best possible relative orientations whereas cryo-EM fitting techniques (rigid and flexible map fitting) were applied on R. norvegicus sGC cryo-EM reconstruction to achieve quaternary structure organization of multi-domain hsGCαβ complex.

1. Methodology

In the current study we have integrated comparative modelling, ab-initio protein modelling, protein-protein docking and electron density map fitting techniques to determine the three dimensional (3D) domain organization of the hsGC quaternary structure.

2.1. Comparative Modelling

Each subunit of hsGC is comprised of four domains as shown in fig. 1. However, a 3D structure is available only for the cyclase domain. Homology models for the other three domains were built for both α and β subunits. Amino acid sequences of hsGCα (Q02108) and hsGCβ (Q02153) were retrieved from UniProt [19] and were aligned using CLC workbench [20] (Supplementary fig. 1). Domain boundaries of individual domains of hsGCα (pseudo-HNOX, PAS & coiled-coil region) and β (HNOX, PAS & coiled-coil region) subunits are shown in fig 1. PSI-BLAST [21] was performed against all the known structures in the Protein Databank (PDB) [22] to select the most closely related template structures for our query sequences. For pseudo-HNOX domain, template identity was less than 20% so we used the I-TASSER algorithm (Iterative Threading ASSEmbly Refinement) [23] to build its protein model. I-TASSER uses threading approach to screen all possible folds in a known PDB structure library by applying four profile-profile alignment approaches which includes Needleman-Wunsch [24], Smith-Waterman alignment algorithms [25], PSI-BLAST profiles and the hidden Markov model [26]. Ιt applies comparative modeling for well-aligned sequence threads, and ab-initio modeling for unaligned sequence threads. Prediction of the final atomic model occurs after a process of iterative template-based fragment assembly simulations. The structures of the other domains were predicted by Modeller 9.17 [27].Modeller applies comparative modelling approach to generate 3D structures of query proteins by recognizing the conserved structural characteristics of homologous proteins [28]. To model the hsGCβ HNOX domain, the crystal structure of Nostoc sp. PCC 7120 HNOX domain (PDB ID: 2O09) [11] was used as template. Furthermore, to model PAS & coiled-coil domains of both hsGCα and β subunits, Manduca sexta PAS domain (PDB ID: 4GJ4) [12] and R. norvegicus coil coiled domain (PDB ID: 3HLS) [13] were used as templates, respectively. Sequence alignments of hsGCαβ PAS and coil-coiled domains with selected templates are given in figure 2. Sequence to structure alignment is helpful in locating conserved sequence regions between the query sequence and selected template. Model building parameters are presented in Table 1. Best models were selected based on the following four parameters; DOPE score [29] GA341 values [30], TM align sore [31] and root means square deviations (RMSD) from their respective template structure. Energy minimization of initial models was done using ModeRefiner [32]. Quality assessments of initial and refined hsGCαβ individual domains models were done using Molprobity [33]. For model visualization and figure illustrations Pymol was used [34].

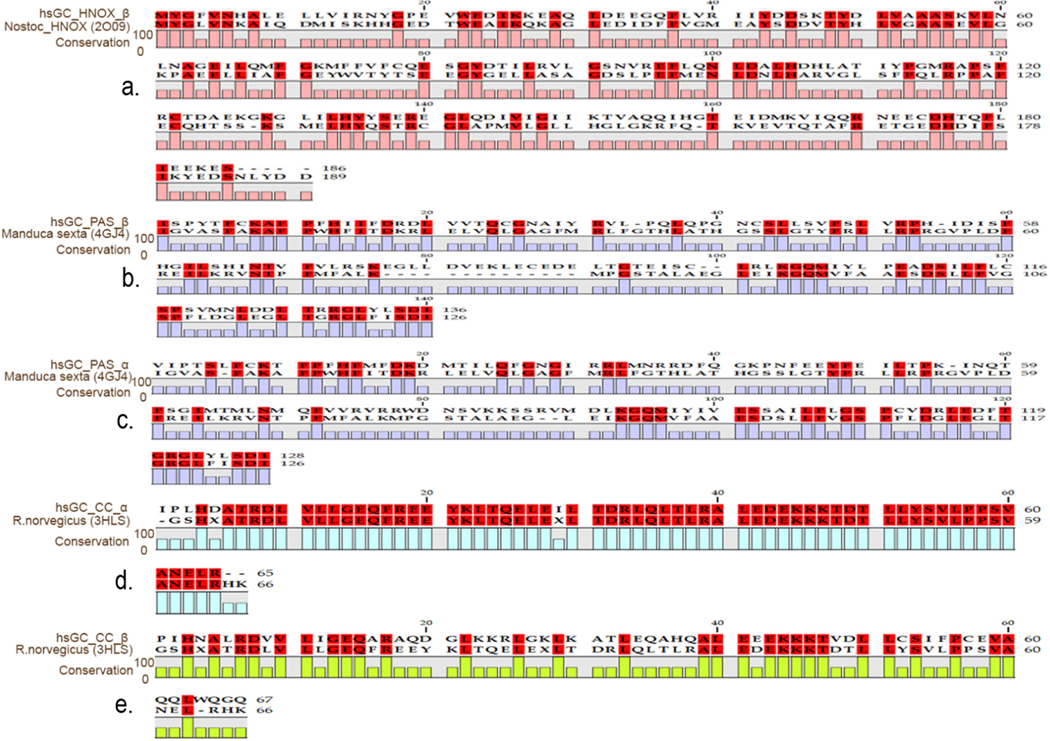

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignments between the hsGC β subunit domains and their homology modeling templates; HNOX (a), PAS (b), coiled-coil (c) and α subunit PAS (d), coiled-coil domain (e) with their respective homologous PDB templates. Red color boxes represent sequence identity whereas conservation bar plots, below sequence alignments, represent percentage identity at a specific residue position.

Table 1.

Homology modelling and I-TASSER related parameters of protein structure prediction for hsGC individual domains.

| Model | Template | Query coverage | Sequence identity | Favored region | Allowed region | GA341 >.7 | DOPE | TM score >.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Models (Modeller) | ||||||||

| β HNOX | 2O09 | 100% | 34% | 95.6% | 98.5% | 1.00000 | −22533.5957 | 0.83 |

| α PAS | 4GJ4 | 99% | 33% | 95.2% | 97.6% | 1.00000 | −14406.33691 | 0.71 |

| β PAS | 4GJ4 | 100% | 36% | 96.1% | 97.9% | 1.00000 | −14001.22650 | 0.73 |

| α Coiled-coil | 3HLS | 92% | 48% | 100% | 100% | 1.00000 | −5539.41762 | 0.52 |

| β Coiled-coil | 3HLS | 100% | 92% | 100% | 100% | 1.00000 | −5033.71436 | 0.75 |

| I-TASSER Model | ||||||||

| αHNOX | Not available | Not Annotated | Not Annotated | 95.3% | 99.2% | N/A | N/A | 0.65 |

2.2. Protein-protein complex modelling

To elucidate the domain order and the relative orientation of multiple domains of α and β subunits, we used template based protein-protein complex prediction approaches. Initially we obtained the relative orientations of neighboring domain pairs such as αHNOX-αPAS, βHNOX-βPAS, αβ-cyclase, αβ-coiled-coil and αβ-PAS through SPRING [35] and COTH [36]. SPRING predicts protein-protein complexes based on the domain order of homologous templates as domain architecture in homologous proteins is generally thought to be conserved [37]. This approach relies on the sequence identity between the target and template sequence of its homologous binding partner to predict protein-protein complex structures. It threads each chain of the query protein complex to extract the conserved two-domain architectures from the known oligomeric structures of a PDB library. By employing a pre-calculated look-up table, multiple combinations of two chain or oligomeric protein-protein complex models against query protein are then generated. These multiple combinations are due to varying template binding partner associations in PDB library. From those combination, a well- oriented complex is then selected by taking SPRING-score as criteria. SPRING score combines threading Z-score, interface contacts and TM-align match score between monomer-to-dimer templates. First, the structural templates were searched against all the neighboring domain pairs (αHNOX (pseudo)-αPAS, βHNOX-βPAS, βHNOX-αPAS, αβ cyclase, αβ-coiled-coil and αβ-PAS) and those known protein structures were selected which have high percentage sequence identity with our query sequences. We observed that only three of our domain pairs that have role in dimerization of hsGC i.e. αβ-cyclase, αβ-coiled-coil, αβ-PAS were giving >30% sequence identity with the known PDB template while continuous domain lying on the same subunit i.e. αHNOX (pseudo)-αPAS, βHNOX-βPAS were giving very low sequence identities with the PDB templates. For low-identity domain pairs we preferred COTH. SPRING and COTH generate thread like map of protein binding partners (see Supplementary fig. 2). Later individual homology models of αβ-cyclase, αβ-coiled-coil and αβ-PAS were superposed over SPRING and COTH predicted outputs to get relatively oriented two-domain protein-protein complexes.

The hsGC protein belongs to the same class III cyclase family as the mammalian adenylate cyclase (AC). In eukaryotes, members of this family use their nucleotide cyclase domains to bind guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) [39]. Moreover, it has been shown that AC binds ATP to its dimeric interface. A sequence alignment shows that AC and sGC share a highly conserved nucleotide binding cyclase domain as well as several catalytic and ligand-binding residues. Since the available crystal structure of hsGCα cyclase domain is in its apoform and given the above mentioned similarities we used the ATP bound crystal structure of AC to identify the catalytic pocket and critical catalytic residues of hsGC cyclase domain. For this purpose, hsGC cyclase domain was superimposed on the corresponding AC domain. The AC catalytic residues, responsible for the nucleotide triphosphate (NTP) binding i.e. D441, N1025, R1029 and K1065 [9] were found conserved at positions D487, D532, N548, R552 and K593 in sGC [40] [41]. Next, and given the experimental evidence that hsGC binds to GTP to convert it into cGMP during NO signaling [9] [38], we built chemical structure of GTP by pymol builder and docked it within the binding pocket of sGC cyclase domain.

2.3. Protein-Protein Docking of N-terminal Domains of hsGCαβ

Various studies reported that the first two N-terminal domains from each subunit are clustered together to make a unique four lobed structure at the N-terminal region of hsGCαβ heterodimer. To model this N-terminal region of hsGCαβ, our next step was to use template free protein-protein complex prediction approach using ClusPro [42]. Current computational structure prediction methods usually give reliable results for no more than two domain protein structures. So protein-protein docking was preferred in ClusPro. We assembled all the domains of hsGCαβ dimer in two steps. From the N-terminal, we first docked pseudo-HNOX to its neighboring, SPRING predicted, αβ PAS domain pair using ClusPro to get a single model. In the second step, we extended the above produced three-domain complex by docking it to β-HNOX domain. Thus we built a four-domain model for the N-terminal of hsGC.

From all possible docked poses we selected those that aligned well with both the SPRING and COTH predicted relative orientations and therefore the chance of predicting wrong interactions and/or conformations of adjacent domains were minimized.

2.4. hsGC dimer Modelling through Cryo-Electron Microscopy Map fitting

2.4.1. Rigid Density Cryo-EM Map fitting

After predicting the relative orientations of adjacent binding partners individually in hsGCα and β subunits as well as the orientation of neighboring domains at the N-terminus of hsGCαβ complex, we built the full length model of hsGC heterodimer by using the cryo-electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) 3D reconstruction of R. norvegicus sGC as a template [16].

During rigid fitting the predicted homology models of different domain assemblies were taken as a rigid bodies and moved inside the 3D reconstruction envelope to achieve the best fit. For this purpose UCSF Chimera Volume viewer and ‘fit in map’ function were used [43]. Moreover, because the input models are big domain assemblies instead of individual domains, the fitting is performed with fewer degrees of freedom, and thus it is a quite challenging task to achieve. This cryo-EM map is used to gain insight into the rearrangement of multiple domains in an active dimeric state. It is a state of the art technique in which the predicted homology model are taken as rigid body objects to move inside the envelope defined by 3D reconstruction. UCSF Chimera Volume viewer module and ‘fit in map’ function was used in rigid density cryo-EM map fitting [43]. During rigid fitting, it is crucial to continuously rotate the view to validate the manual map fitting from several angles. As we are taking dimeric structures as input models instead of individual domains. These two-domain structures allow less degree of freedom while structure’s rotation and adjustment in cryo-EM. So it is extremely difficult to adjust these protein complexe within the narrow space of map with minimum steric clashes. Because of that we used the UCSF Chimera ‘fit in map’ function and transformed the predicted model into a map [44]. Then a cross-correlation was applied to fit the model generated map inside the cryo-EM reconstruction and the map fitting was ranked according to the corresponding cross-correlation coefficient.

The resolution of the cryo-EM model used as a template was 30Å, while the contour level of the density map was set at 0.731.The sGC R. norvegicus cryo-EM model is comprised of two modules; the upper and the lower one. The upper module is further composed of four lobes while the lower module has only two lobes. Between the upper and lower modules, there are two long juxtaposed α-helices which connect the N-terminal domains with the C-terminal cyclase domain [16].

First, the predicted N-terminal heterodimeric model, which is comprised of pseudo-HNOX, αβ-PAS and β-HNOX, was docked into the four lobes of the upper module by rigid fitting. Second, manual adjustments of the proteins’ positions performed to best fit into the electron density Third, biochemical constraints such as chemical cross-linking and solvent accessibility data was considered during map fitting. Fourth, the αβ-coiled-coils and the cyclase dimer were put into the central thin stalk region and the lower module, respectively.

2.4.2. Subunit Modelling

So far, a protein assembly composed of all the domains, properly oriented but without connections linking them has been generated. Given that no entire structure of any homologous protein was available, connections between the domains were generated by AIDA (ab initio Domain Assembly) server. AIDA takes homology models of individual domains together with the amino acid sequences of query proteins, assembles all the consecutive domains based on domain-domain interactions and connects them with flexible linkers [45]. The final model of α and β subunits were the one found at the lower energy state through the built-in energy minimization protocol of AIDA.

2.4.3. Flexible Density Cryo-EM Map fitting

For us it was of exceptional significance to achieve the correct relative orientation of the subunits since it is known from numerous studies that the only way of signal transduction from N-terminus to C-terminus of hsGC is the interface regions between neighboring domains [47–49]. Therefore, an accurate model would be especially helpful in understanding the signal transduction mechanism.

Final structural arrangements and domain orientation in the complete heterodimeric model generated by AIDA was done by Flexible Density cryo-EM Map fitting. For this purpose, the Macromolecular Visualization and Processing MVP-fit [46] tool was used and loop regions were considered to be flexible points allowing the movement of individual domains. During the fitting, local flexible adjustment and rigid-body arrangements to adjust the structure inside the density map [30] were allowed and prior experimental knowledge was taken into account to adjust αβ subunits. It has been reported in various studies that the only way of signal transduction from N-terminus to C-terminus of hsGC is the interface regions between neighboring domains [47–49]. So their correct relative orientation will be helpful in understanding the signal transduction mechanism. Fine tuning of domains inside the cryo-EM map depends on the spatial constraints of their corresponding lobes.

Final predicted model of hsGCαβ heterodimer was refined through energy minimization in AMBER14 [50]. For standard amino acids we used ff14SB force field [51] while NO-Heme-H105 group of hHNOX domain was parameterized through quantum calculation in mcpb.py module of AMBER14 [52]. Afterwards, system was subjected to energy minimization (20000 steps) in AMBER14 to remove all the steric clashes. For structure quality assessment final predicted model was submitted for analysis to RAMPAGE [53].

3. Results

3.1. Homology Models of Individual hsGCαβ Domains

Sequence comparison of hsGC α and β subunits revealed 33% sequence identity and 47% sequence similarity (Supplementary fig. 1). Pairwise sequence alignments of individual hsGC domains with respect to their corresponding template sequences are shown in fig 2 while predicted individual models are given in supplementary fig 3. Homology modeling parameters are presented in Table 1. For model selection the criteria of lowest discrete optimization protein energy (DOPE) potential value and of GA341 score equal to 1 were applied. Pseudo-HNOX domain is functionally and structurally unannotated region, therefore we built its model using threading approach in I-TASSER. Pseudo-HNOX domain share similar structural fold like β-HNOX which is composed of a small α helical subdomain and a larger mixed α/β subdomain at C-terminal but it lacks the heme-binding YxSxR (Tyr-x-Ser-x-Arg) motif at the binding pocket. Root- mean-square deviations (RMSD) between the predicted models and their respective templates were from 0.2 to 0.6Å. The models’ global structure quality was assessed by TM align score to be >0.5 which indicates a reliable model. Molprobity analysis of final models revealed that more than 95% of residues are in favorable and allowed regions of Ramachandran (see Table 1).

3.2. Modeling of adjacent domains

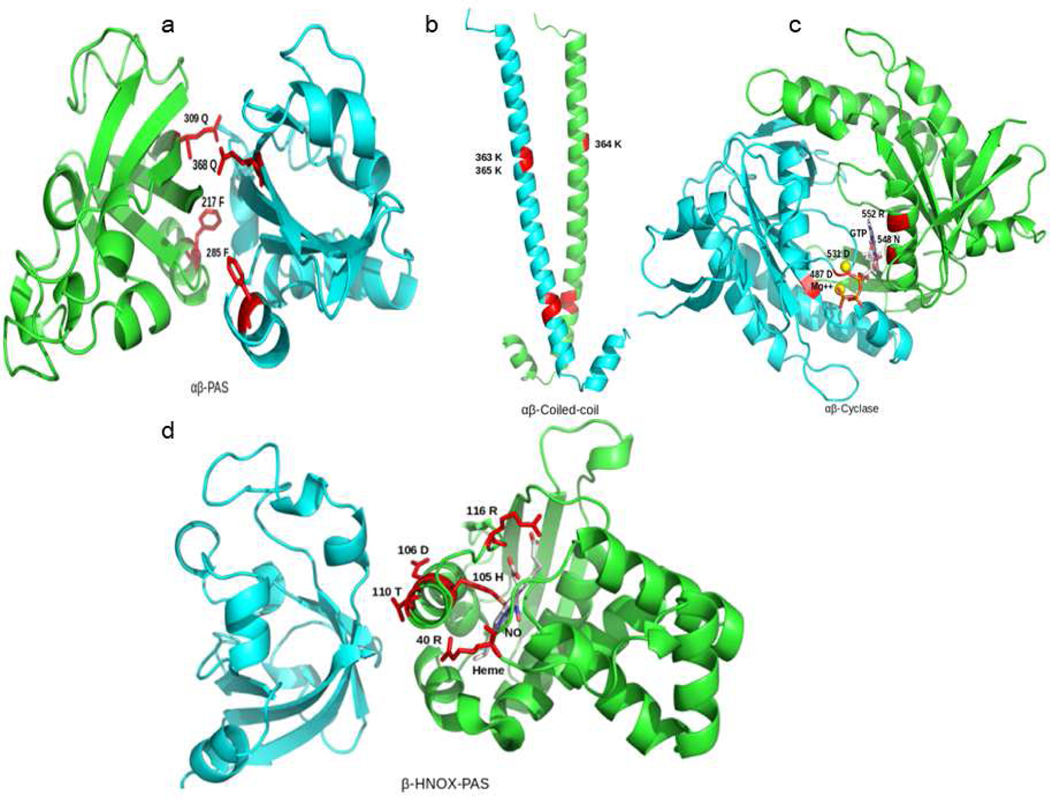

Domain order and the relative orientation of adjacent domains of α and β subunits were predicted using SPRING and COTH. Selection of the SPRING predicted complexes of αβ PAS, αβ coiled-coil and αβ cyclase were based on their maximum sequence identity in maximum query coverage of the homologous template as well as normalized probability percentage. The hsGC αβ-PAS predicted dimer has 31% identity in 86% template’s sequence coverage and showed 100% normalized probability percentage which indicates that the relative orientation of the two αβ PAS domains in the complex is conserved between template and model. Likewise, αβ coiled-coil and αβ cyclase complexes showed 99.9% and 100% probability values, respectively, which indicate conserved patterns of domain orientations between templates and predicted models. As mentioned above, SPRING and COTH just depicts the relative orientations of adjacent domains in the form of a thread like map where the helices are placed without further details of secondary structure to be evident. Therefore the next step was to superpose the homology models on the SPRING predicted thread-like maps (see Supplementary fig. 3) and to predict protein-protein complexes of neighboring domain in best possible conserved conformation (shown in Figure 3). Root mean square deviations (RMSD) were less than 2.5 Å for all superimposed structures.

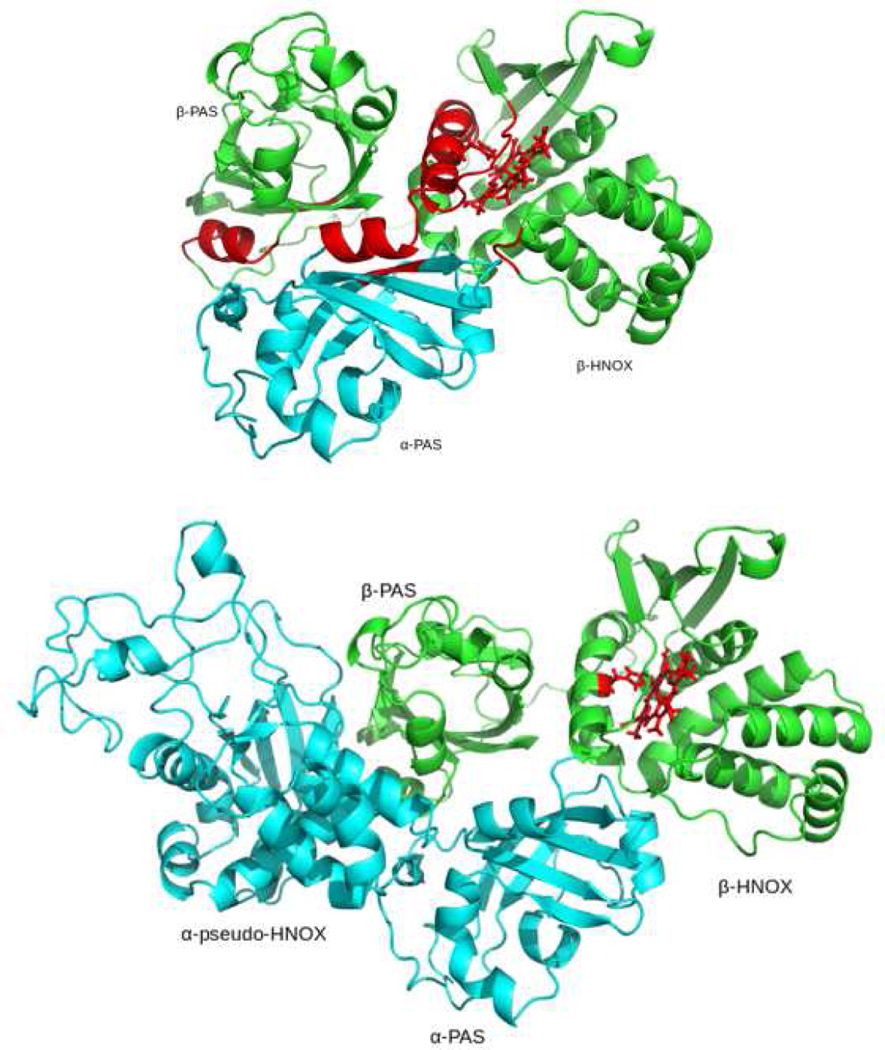

Fig. 3.

Dimeric domains orientations of αβ PAS (a), αβ coiled-coil (b), αβ cyclase (c) and βHNOX-βPAS (d) predicted through template based single chain threading approach (SPRING & COTH). In dimeric model of αβ PAS (a), αβ coiled-coil (b), αβ cyclase (c), individual domain models of hsGCα subunits are shown in cyan color while domain models of hsGCβ chains are shown in green color The while neighboring domains of same subunit βHNOX-PAS dimeric model, individual models of βHNOX and βPAS are shown in green and cyan respectively. Residues lying at the interface of dimeric domains are labelled and highlighted as sticks (red).

To validate the predicted relative orientation of human αβ-PAS, αβ-coiled-coil, αβ-cyclase and βHNOX-βPAS complexes with experimental data of their homologs, we analyzed the interface residues of these two-domain models (see Supplementary fig. 4). In αβ-PAS complex, Q368, F285 residues from αPAS (cyan) and Q309, F217 of β PAS (Figure 3a) were observed at dimeric interface. In αβ-coiled-coil complex, residues (K363, K365) in α-coiled-coil and K-364 in β coiled-coil domain were seen at dimeric interface (Fig. 3b). These residues are also reported to be involved in dimerization of sGC through SAXS experiments. In αβ-cyclase, we obtained the dimeric orientation through SPRING by using adenylate cyclase dimer as template while retaining the binding mode of GTP ligand at its dimeric interface (Supplementary fig. 4c). Conserved dimeric interface residues D487 and 532D (α-cyclase) N548, R552 and K938 (β-cyclase) were also observed to have interaction with GTP and Mg2+. αβ-cyclase dimeric domains in complex with GTP bound complex is given in figure 3c. In COTH predicted βHNOX-βPAS protein-protein complexes, we selected βHNOX-βPAS dimer based on the orientation of helix-F. In our selected βHNOX-βPAS dimeric complex, helix-F is facing the neighboring PAS domain and found that 105H,106D and 116R that are present at the periphery of the β-HNOX are interacting with the NO and heme meioty. Out of these residues 106D and 110T that are part of Helix-F (figure 3d) might interact with the neighboring β-PAS domain.

Relative orientations of our SPRING and COTH predicted dimeric domains complemented the experimentally protein-protein interactions of prokaryotic and eukaryotic sGC dimeric domains.

3.3. N-terminal domain cluster Prediction using Protein-Protein Docking

To predict the N-terminal region of hsGCαβ heterodimer, we clustered four domains together through protein-protein docking in ClusPro server. To that aim, we took αβ-PAS dimer model as single initial input structure and docked it with β-HNOX model. It predicted multiple poses of three domain model using all the coefficients. From all predicted poses, we selected best pose by superposing our COTH predicted βHNOX-βPAS dimer to retain the approximate relative orientation of neighboring domains (figure 3d). Energy value of our selected ClusPro predicted three-domain protein complex (αPAS- βPAS- βHNOX) was −801.6 kcal/ mol. Three domain complex of αPAS- βPAS- βHNOX is shown in fig. 4a. Helix and residues highlighted in red depicts the common pattern of helix-F and dimeric interface residues of βHNOX-βPAS dimer (see figure3d) with our three domain complex. Then we extended this three-domain cluster and used it as a receptor to dock with pseudo α-HNOX domain. Experimental data lacks structural annotation which defines the orientation of pseudo α-HNOX domain with respect to it adjacent α-PAS domain. So the best conformation of four domain complex was selected only on lowest energy value of −865.1 kcal/mol among all predicted conformers. Predicted cluster of four N-terminal domains is given in fig. 4b.

Fig. 4a:

Three domain model of αβ-PAS dimer with the βHNOX domain. 4b: N-terminal four domain cluster (α-pseudo-HNOX- αPAS- βPAS- βHNOX) of hsGCαβ dimer. All α subunit domains are showed in green color and β subunit domains are shown in cyan color. Experimentally known functionally critical hotspots areas on the interface are highlighted in red. Prosthetic group of β HNOX is also rendered in red.

3.4. Density Map Fitting Dimeric Models

We first docked SPRING and COTH predicted thread like dimeric domain’s framework inside the density map. Left side of upper lobe of cryo-EM map is bit bulkier than the right side (see fig.5). Studies reported that pseudo-HNOX region present at N-terminal region of hsGCα subunit is composed of 270 amino acid (aa) while N-terminal β-HNOX domain is composed of 186 residues. Eighty four amino acid difference between both these domains suggested the fitting of pseudo-HNOX of hsGCα subunit at the bulkier region of cryo-EM while β-HNOX-βPAS dimer opposite to it (fig.5). Orientation of SPRING and COTH predicted binding partners at the upper lobe of cryo-EM map was adjusted by superposing it to our N-terminal four domain model predicted through protein-protein docking.

Fig. 5.

SPRING and COTH predicted dimeric models docked into the electron density map of R. norvegicus sGC. Cyan and green color represents the dimeric structures of α and β H-NOX-PAS respectively. While blue and red describes the relative conformation of αβ coiled-coil and αβ cyclase dimers

3.5. Flexible Density Map Fitting of Subunit Models

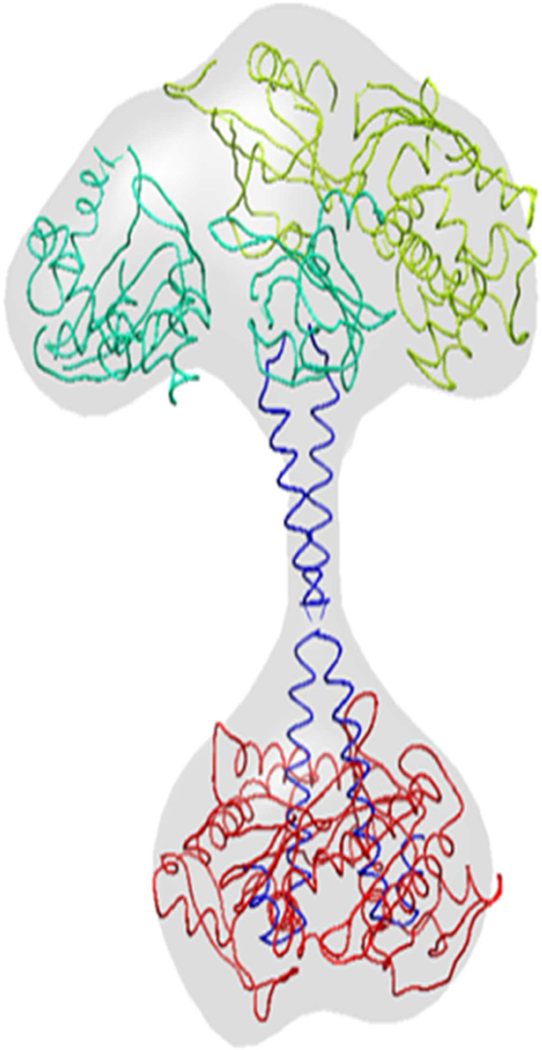

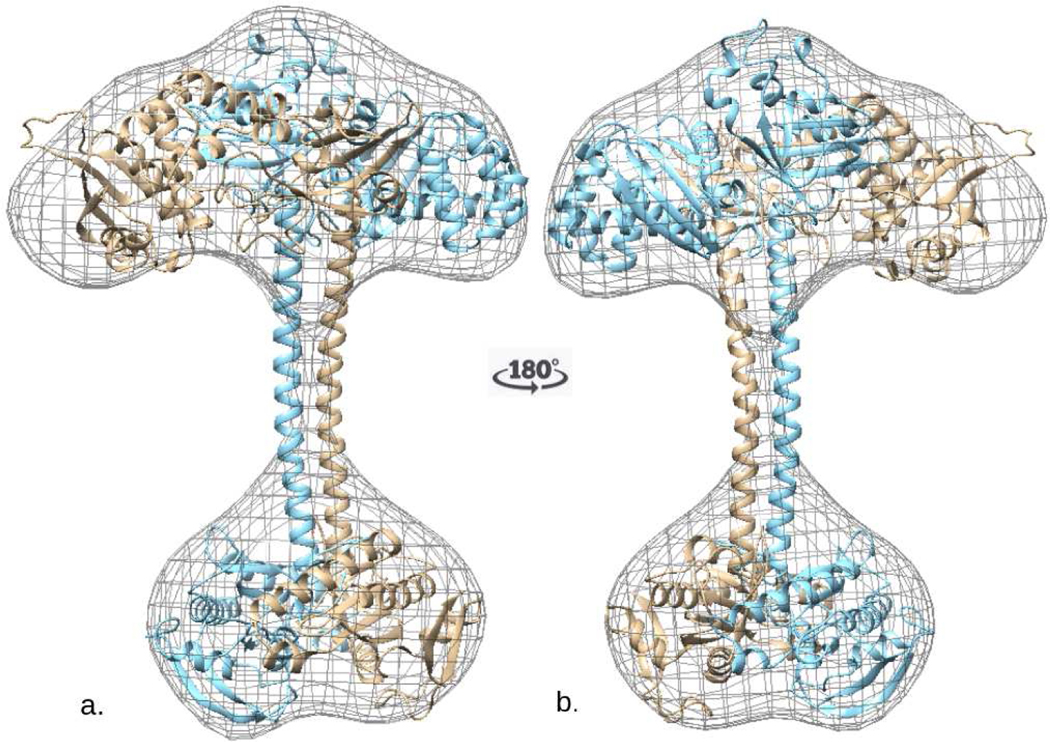

Rigid body map fitting resulted in a well oriented full length hsGCαβ heterodimer in which continuous domains of individual subunit are not attached with each other. In order to link all the domains from N-terminal to C-terminal, we used individually assembled α and β chains as inputs. In AIDA assembled chain, we ensured the correct orientations of partner domains by aligning the subunits with our SPRING, COTH and protein-protein docking models. Correctly orientated assembled chains were accounted for flexible fitting in MVP fit tool. Figure 6a and 6b represents the hsGC α and hsGC β chains in laid on the cryo-EM density map of hsGC α and β respectively. In the upper module of reconstruction map, four domains are clustered, out of which αβ-PAS are contributing in the dimer formation. Molecular organization of full length hsGCαβ heterodimer shows a parallel arrangement of both the subunits which is attributed by mediated two thin juxtaposed coiled-coil α-helices. These long stalk like helices are connecting regulatory domains of N-terminal with the C-terminal cyclase domains and also makeup the dimeric interface of the predicted hsGCαβ model. β-HNOX domain is in complex with heme group and NO molecule while GTP and Mg2+ is present at the dimeric interface of the αβ cyclase domains of our final model (fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

a). Flexible cryo-EM map fitting of atomic models inside the cryo-EM density Map with 180 degree rotation are shown (b). The alpha and beta subunits of hsGC are represented by wheat and cyan colors respectively.

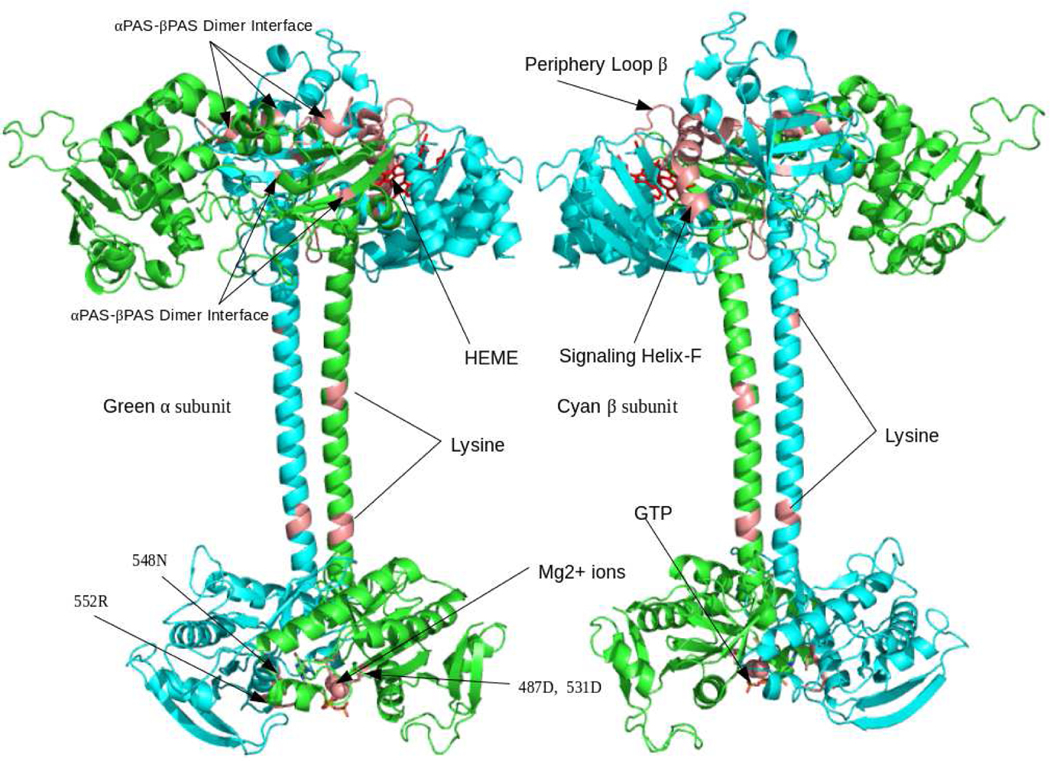

Fig. 7.

Homology model of entire hsG heterodimer in complex with NO-HEME moiety at regulatory (βHNOX) domain while GTP and Mg 2+ ion at catalytic region (cyclase dimer). In the predicted hsGC heterodimer, α chain is highlighted in green and hsGCβ is shown in cyan color. Salmon color regions throughout the structure illustrated the dimeric interface critical regions such as signaling Helix-F, Loop β, H105, D106, T110 (βHNOX-βPAS), F285, Q368 (α-PAS), F217, Q309 (β-PAS), K363,K365 (α-coiled-coil), K364 (β-coiled-coil), D487,D531 (α-cyclase) and N548,R552 (β-cyclase).

Quality assessment of hsGCαβ heterodimer in Molprobity analysis revealed 85.2% (1018/1195) of all residues were in favored regions while 92.7% (1108/1195) residues were in allowed regions. We reasonably retained the multi-domain architecture of eukaryotic sGC in our in silico predicted model by using the structural information available through biochemical studies and cryo-EM 3D reconstruction of R. norvegicus sGC.

4. Discussion

Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) is the primary receptor of cGMP signaling pathway involved in Nitric-oxide mediated production of cGMP molecules and activate a repertoire of downstream signaling pathways that induces smooth muscles relaxation and vasodilation as well as regulates proliferation of smooth muscle cells and platelet aggregation [1–2]. From 30 years of research, significant information has been reported on individual sGC domain structures but little has been known on the domain architecture in an active hsGC structure. Along with this, structural events involved in NO signal perception, regulation and propagation by sGC molecule in higher organism are still elusive. It has been reported in various studies that NO diffuse through the cell membrane and binds to a ferrous heme-iron meioty of hsGCβ-HNOX domain to form a transient 6 coordinate heme-NO complex [54]. This intermediate complex is highly unstable and immediately breaks the proximal histidine bond with ferrous ion (Fe2+) to produce a 5-coordinate heme complex state [55]. This bond breakage triggers slight movement of helix-F in βHNOX domain which brings about conformational change that is transmitted to the C-terminal cyclase domains [56]. This bond breakage between histidine and heme iron is thought to activate N-terminal cyclase domains but how this N-terminal to C terminal domains crosstalk/communication takes place and how this heme (iron)-histidine bond breakage signal propagates from βHNOX domain and directs the activation and folding of entire structure is still unclear [6].

The molecular architecture of full length hsGCαβ heterodimer predicted in the current study is strengthened by validating it through experimental studies. Structural similarities can be present even in proteins that share little sequence similarity, as structure is more strongly conserved than sequence. Relative position of the multiple domain decides the inter domain communication as well as the folding behavior of the proteins. Complex topology of hsGCαβ heterodimer was achieved by borrowing the conserved key residues at adjacent domain interfaces of homologs that influence their correct orientation during hsGCαβ folding mechanism (fig.7). Use of dimeric domain pairs as rigid bodies during density map fitting in cryo-EM actually narrow down the degree of freedom during manual adjustment. To propose the complete structure of hsGC, we tried to link the biological information with different structural and functional aspects of multi-domain protein.

It is extremely difficult to predict a plausible conformer of hsGCαβ heterodimer with right orientation of multiple domains. Even though the template identities in case of dimeric domains were not high enough but still we modelled the entire heterodimeric structure of hsGCαβ with a reasonable and justifiable multi-domain organization of eukaryotic sGC.

It is an established concept that conserved domains interact with more or less similar inter-domain geometry [37]. Keeping in view the relationship between the protein sequence and conservation of geometry among neighboring domains, we predicted the organization of the interaction surfaces in adjacent domain of same subunit as well as dimeric subunits from already known PDB structures and their related literature.

Solvent accessibility of βHNOX-PAS (1–385 a.a) in contrast with an individual β-HNOX domain (1–194); results reported that solvent accessibility of signaling helix-F reduces probably due to the burial of signaling helix-F at the interface of β-HNOX-PAS domains [47]. This experimental data were used in this work to find the relative orientation inside the density map. Furthermore, mutagenesis study of specific periphery residues variants of signaling helix-F (D106K, T110R) and adjacent loop R116E drastically decreases the NO simulated cyclase activity. Mutation of single residue from signaling helix (D106K) mutation causes more than 500 fold inhibition of catalytic activity which is involved in cGMPs production. This aspartic acid residue lies between H-NOX and PAS domains [15].

Histidine Kinase Signal Transduction (HKST) H-NOXA domain has structural similarity with PAS domain. PAS domain fold is commonly found in sensory proteins which are essential to sense the redox potential. PAS sensory domain detects small molecules (oxygen & light) and play a vital role in signal transduction. In sGC, PAS domain maintains the conserved dimeric pattern and it is postulated that they may anchor a secondary allosteric regulatory region in sGC. Being an evolutionary remnant, PAS domain may have role in sensing the Helix-F detachment signal from its preceding βHNOX domain. Dimer conformation of sGC is critical for signal transduction. It is known that seven residues from N-terminal residues of β-PAS domain interface are essential for dimerization with α PAS domain. A study validated the presence of similar NpSTHK-type dimer interface region in sGC by substituting alanines to eight putative PAS domain dimer interface residues. Out of those eight mutations two residues i.e. (F285, Q368) from α subunit two residues i.e. F217, Q309 from β subunit were found conserved [7] (see fig.7). Mutations of these residues significantly decrease the dimerization and NO-dependent signaling activity of sGC. Moreover, activity inhibition of sGC may be due to the fact that the overall dimer conformation is disturbed which is a prerequisite to sense the signaling helix [57] [7]. Our predicted hsGC αβ-PAS model folds similarly as HKST H-NOXA domain dimerizes with its counterpart. Therefore we subjected the predicted αβ-PAS dimeric model to extend the multi-domain assembly of entire hsGC using protein- protein docking and cryo-EM map fitting.

Chemical cross-linking studies confirm a parallel arrangement of coiled-coil domains. Dimer structure has lysine residues, lying parallel to each other and reported to be involved in the dimerization of this region. Alpha coiled-coil has K363, and K365 parallel to corresponding domain K364 these residues were under optimal distance for chemical cross-linking [14]. Furthermore, C-terminal region of coiled-coil domain which is essential for hetero-dimerization is also required for hsGC simulating activity.

Adenylate cyclase (AC) domain is structurally homologous to sGC [58–59]. Therefore, activation mechanism of AC might be able to give insight in understanding the catalytic activity of sGC. sGC cyclase domains have conserved homologous motifs with AC. The residues which are required for cyclase catalytic activity are also conserved. For instance, α subunit cyclase D487 and D531 have electrostatic interaction with two Mg2+ ions, which further cyclize the nucleotide ligands (GTP, ATP) by releasing pyrophosphate. These residues are critical for the catalytic activity of cyclase. Moreover, the β subunit cyclase N548 has been proposed to attract the ribose ring. There are some more residues such as E473 and C541 which are thought to be necessary for purine base recognition. In addition, in both α, β subunits R573 and R552 are thought to have robust electrostatic interactions with GTP triphosphate group. The binding pocket residues convert the GTP to cyclic GMP (cGMP )[20]·, which may act as a secondary message to stimulate various downstream pathways with a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological implications.

To solve the atomic structures of several individual domains and a complete molecular architecture of sGC, tangible experimental research work has been done which resulted in a cryo-electron density map of R. norvegicus. However, the full structure of the human sGC remains to be determined. In the present study, we employed comparative modelling approaches to build individual models for the individual protein domains and then assembled them into their correct relative orientation using the single chain threading approaches. As hsGC is a multi-domain protein complex, after getting the plausible orientation of adjacent domains, we used protein-protein docking to figure out the orientation of successive domains in a folded state. To validate the aforementioned multi-domain assembly approach, we also performed sequence based ab inito multi-domain assembly of hsGC and generated a model of α and β subunits. Assembled structures of both subunits were then used for flexible fitting by MVP fit tool [29] in which COTH and SPRING [24] generated orientations of two adjacent domain structures (αβ-PAS, αβ-coiled-coil, αβ-cyclase), as well as protein-protein docking based conformation of multiple domains (α-HNOX/β-HNOX, αβ-PAS & αβ-PAS/-β-HNOX) was retained. We predicted a model of the hsGC heterodimer by fulfilling the spatial restraints reported in already available cross-linking studies, crystal structures and cryo-EM density maps of homologous proteins. The proposed model is consistent with the biochemical structure to function data because of the incorporation of physical and biochemical constraints of sGC. This model will become the starting point for understanding the dynamic characterization of sGC, to disclose the signal transduction mechanism between domains.

Thus we provided the structural insight into the molecular architecture of sGC in its active folded state which could help in understanding the catalytic and regulatory mechanism of sGC heterodimer.

5. Conclusion

The structure of the enzyme is important to understanding its role in performing vital functions it plays in controlling blood pressure and smooth muscle relaxation. Current study is primarily focused on understanding the structural organization of the human soluble Guanylate Cyclase (hsGC). Modeling of hsGC is a very non-trivial study mainly because it involves the assembly of multiple domain structures.

We introduced a new protocol to build a high-resolution complex structural model of hsGC by the combination of the state-art-the-art tertiary and quaternary protein structure prediction algorithms (using I-TASSER and SPRING), followed by the cryo-EM density map fitting (using MVP-fit). The detailed model analyses unveil close consistency of the overall topology and domain orientation of the predicted model with the experimental data of ligand binding and peptide docking, which demonstrate the reliability and robustness of the hybrid structural model. This study would help to unveil the inter-domain communication upon nitrogen oxide binding, which is believed to play a significant role in the hsGC associated human diseases.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Sequence identity (%), query coverage (%) and Normalized Probability (%) of SPRING predicted αβ-PAS, αβ-coiled-coil and αβ-cyclase dimeric domain models of hsGC while Z-score value is given for COTH predicted βHNOX-βPAS model.

| Dimer Models | Identity (%) | Coverage (%) | Normalized. Probability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPRING predicted Complexes | |||

| αβ-PAS | 31.3 | 86.0 | 100 % |

| αβ-Coiled-coil | 67.1 | 93.2 | 99.93 % |

| αβ-Cyclase | 88.2 | 87.6 | 100 % |

| COTH predicted consecutive complex | |||

| βHNOX-βPAS | 25 | 75 | Z-score (>2.5) |

| 3.29 | |||

Highlights.

Modeling of sGC domains using state-of-the-art methods

Chain orientation of complex structure modeled by dimeric threading

Biological constraints are used for further domain and chain orientation refinement

sGC subunits rigid and flexible cryo-EM density map fitting.

Acknowledgments:

Support by the High Performance Computing facility of “Zhang Lab” University of Michigan is acknowledged.

Funding: The authors would also like to thank the International Research Support Initiative Program (IRSIP), National Research Program for Universities (NRPU-4050) by Higher Education Commission (HEC) Pakistan and 2216 Research Fellowship Program for International Researchers by TUBITAK. This research was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences [GM083107, GM116960], National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [AI134678], and National Science Foundation [DBI1564756].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Loscalzo J, Welch G, Nitric oxide and its role in the cardiovascular system, Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. (1995). doi: 10.1016/S0033-0620(05)80001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Warner TD, Mitchell JA, Sheng H, Murad F, Effects of cyclic GMP on smooth muscle relaxation, Adv. Pharmacol. 26 (1994) 171–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koesling D, Russwurm M, Mergia E, Mullershausen F, Friebe A, Nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase: Structure and regulation, in: Neurochem. Int, 2004: pp. 813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Friebe A, Mergia E, Dangel O, Lange A, Koesling D, Fatal gastrointestinal obstruction and hypertension in mice lacking nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 (2007) 7699–704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bredt DS, Endogenous nitric oxide synthesis: biological functions and pathophysiology., Free Radic. Res. 31 (1999) 577–596. doi: 10.1080/10715769900301161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pan J, Yuan H, Zhang X, Zhang H, Xu Q, Zhou Y, Tan L, Nagawa S, Huang ZX, Tan X, Probing the Molecular Mechanism of Human Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Activation by NO in vitro and in vivo, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017). doi: 10.1038/srep43112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ma X, Sayed N, Baskaran P, Beuve A, Van Den Akker F, PAS-mediated dimerization of soluble guanylyl cyclase revealed by signal transduction histidine kinase domain crystal structure, J. Biol. Chem. 283 (2008) 1167–1178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706218200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zhou Z, Gross S, Roussos C, Meurer S, Müller-Esterl W, Papapetropoulos A, Structural and functional characterization of the dimerization region of soluble guanylyl cyclase., J. Biol. Chem. 279 (2004) 24935–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Allerston CK, von Delft F, Gileadi O, Crystal Structures of the Catalytic Domain of Human Soluble Guanylate Cyclase, PLoS One. 8 (2013). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA, Structure and regulation of soluble guanylate cyclase, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81 (2012) 533–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-050410-100030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ma X, Sayed N, Beuve A, Van Den Akker F, NO and CO differentially activate soluble guanylyl cyclase via a heme pivot-bend mechanism, EMBO J. 26 (2007) 578–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Purohit R, Weichsel A, Montfort WR, Crystal structure of the Alpha subunit PAS domain from soluble guanylyl cyclase, Protein Sci. 22 (2013) 1439–1444. doi: 10.1002/pro.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ma X, Beuve A, van den Akker F, Crystal structure of the signaling helix coiled-coil domain of the beta1 subunit of the soluble guanylyl cyclase., BMC Struct. Biol. 10 (2010) 2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fritz B, Roberts S, Ahmed a, Breci L, Li W, Weichsel a, Brailey J, Wysocki V, Tama F, Montfort W, Molecular model of a Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Fragment Determined by Small-Angle X-ray Scattering and Chemical Cross-Linking., Biochemistry. 52 (2013) 1568–1582. doi: 10.1021/bi301570m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Underbakke ES, Iavarone AT, Marletta MA, Higher-order interactions bridge the nitric oxide receptor and catalytic domains of soluble guanylate cyclase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110 (2013) 6777–6782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301934110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Campbell MG, Underbakke ES, Potter CS, Carragher B, Marletta MA, Single-particle EM reveals the higher-order domain architecture of soluble guanylate cyclase, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (2014) 2960–2965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400711111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ryabov Y, Fushman D, Structural assembly of multidomain proteins and protein complexes guided by the overall rotational diffusion tensor, J. Am. Chem. Soc. (2007). doi: 10.1021/ja071185d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jolley CC, Wells S, Fromme P, Thorpe MF, Fitting low-resolution cryo-EM maps of proteins using constrained geometric simulations, Biophys. J. (2008). doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge, Nucleic Acids Res. (2019). doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sequencing H, CLC Genomics Workbench-2016, Workbench. (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [21].Altschul SF, Madden TL, a Schaffer A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ, Blast and Psi-Blast: Protein Database Search Programs, Nucleid Acid Res. (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].ProteinDataBank, RCSB Protein Data Bank - RCSB PDB RCSB Protein Data Bank - RCSB PDB, Hum. Serum Albumin. (2013). doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang Y, I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction, BMC Bioinformatics. 9 (2008). doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Needleman SB, Wunsch CD, A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins, J. Mol. Biol. (1970). doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Smith TF, Waterman MS, Identification of common molecular subsequences, J. Mol. Biol. (1981). doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Karplus K, Barrett C, Hughey R, Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies, Bioinformatics. (1998). doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.10.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen M-Y, Pieper U, Sali A, Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER., Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 2 (2007) Unit 2.9. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0209s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Burke DF, Deane CM, Nagarajaram HA, Campillo N, Martin-Martinez M, Mendes J, Molina F, Perry J, Reddy BVB, Soares CM, Steward RE, Williams M, Carrondo MA, Blundell TL, Mizuguchi K, An iterative structure-assisted approach to sequence alignment and comparative modeling, Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. (1999). doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shen M, Sali A, Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures, Protein Sci. (2006). doi: 10.1110/ps.062416606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Eswar N, Y.S M. and S. A, Eramian David, Webb Ben, Protein structure modeling with MODELLER., Methods Mol. Biol. (2008). doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang Y, Skolnick J, Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality, Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 57 (2004) 702–710. doi: 10.1002/prot.20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Xu D, Zhang Y, Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization, Biophys. J. 101 (2011) 2525–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography, Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66 (2010) 12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].DeLano WL, The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger LLC Wwwpymolorg. Version 1. (2002) http://www.pymol.org. doi:citeulike-article-id:240061. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Guerler A, Govindarajoo B, Zhang Y, Mapping monomeric threading to protein-protein structure prediction, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53 (2013) 717–725. doi: 10.1021/ci300579r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mukherjee S, Zhang Y, Protein-protein complex structure predictions by multimeric threading and template recombination, Structure. 19 (2011) 955–966. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gao M, Skolnick J, Structural space of protein-protein interfaces is degenerate, close to complete, and highly connected, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (2010) 22517–22522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012820107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Poulos TL, Soluble guanylate cyclase, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. (2006). doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Denninger JW, Marletta MA, Guanylate cyclase and the.NO/cGMP signaling pathway, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 1411 (1999) 334–350. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Childers KC, Garcin ED, Structure/function of the soluble guanylyl cyclase catalytic domain, (2018) 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2018.04.008.Structure/function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dessauer CW, Scully TT, Gilman AG, Interactions of forskolin and ATP with the cytosolic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase, J. Biol. Chem. (1997). doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kozakov D, Hall DR, Xia B, Porter KA, Padhorny D, Yueh C, Beglov D, Vajda S, The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking, Nat. Protoc. 12 (2017) 255–278. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Goddard TD, Huang CC, Ferrin TE, Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera, J. Struct. Biol. 157 (2007) 281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chen JE, Huang CC, Ferrin TE, RRDistMaps: A UCSF Chimera tool for viewing and comparing protein distance maps, Bioinformatics. 31 (2015) 1484–1486. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu D, Jaroszewski L, Li Z, Godzik A, AIDA: Ab initio domain assembly server, Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014). doi: 10.1093/nar/gku369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Xu Dong and Zhang Yang*, MVP-Fit: A Convenient Tool for Flexible Fitting of Protein Domain Structures with Cryo-Electron Microscopy Density Map, (2010). https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/MVP-Fit/manuscript.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Underbakke ES, Iavarone AT, Chalmers MJ, Pascal BD, Novick S, Griffin PR, a Marletta M, Nitric Oxide-Induced Conformational Changes in Soluble Guanylate Cyclase, Struct. Des. 22 (2014) 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yoo BK, Lamarre I, Martin JL, Negrerie M, Quaternary structure controls ligand dynamics in soluble guanylate cyclase, J. Biol. Chem. (2012). doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Haase T, Haase N, Kraehling JR, Behrends S, Fluorescent fusion proteins of soluble guanylyl cyclase indicate proximity of the heme nitric oxide domain and catalytic domain, PLoS One. 5 (2010). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Case DA and Betz RM and Botello-Smith W. and Cerutti DS and Cheatham TE III and Darden TA and Duke RE and Giese TJ and Gohlke H. and Goetz AW and Homeyer N. and Izadi S. and Janowski P. and Kaus J. and Kovalenko A. and Lee TS and S., AMBER 2016, Univ. California, San Fr. (2016). doi: 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C, ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11 (2015) 3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Maryam A, Siddiqi A, Mylonas E, Khalid R, Kokkinidis M, Dynamic Characterization of the Human Heme Nitric Oxide/Oxygen (HNOX) Domain under the Influence of Diatomic Gaseous Ligands, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (2019) 698. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, de Bakker PIW, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation., Proteins. 50 (2003) 437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ballou DP, Zhao Y, Brandish PE, Marletta MA, Revisiting the kinetics of nitric oxide (NO) binding to soluble guanylate cyclase: The simple NO-binding model is incorrect, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99 (2002) 12097–12101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192209799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Karow DS, Pan D, Tran R, Pellicena P, Presley A, Mathies RA, Marletta MA, Spectroscopic characterization of the soluble guanylate cyclase-like heme domains from Vibrio cholerae and Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis, Biochemistry. 43 (2004) 10203–10211. doi: 10.1021/bi049374l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zhou Z, Gross S, Roussos C, Meurer S, Müller-Esterl W, Papapetropoulos A, Structural and functional characterization of the dimerization region of soluble guanylyl cyclase, J. Biol. Chem. (2004). doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Rothkegel C, Schmidt PM, Atkins D-J, Hoffmann LS, Schmidt HHHW, Schröder H, Stasch J-P, Dimerization region of soluble guanylate cyclase characterized by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in vivo., Mol. Pharmacol. 72 (2007) 1181–1190. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.036368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].John SRS Tesmer1 JG, Roger K. Sunahara2, Roger A. Johnson3, Gilles Gosselin4, Alfred G. Gilman2, Two-metal-Ion catalysis in adenylyl cyclase., Science (80-. ). 756–60 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sürmeli NB, Müskens FM, Marletta MA, The influence of nitric oxide on soluble guanylate cyclase regulation by nucleotides: Role of the pseudosymmetric site, J. Biol. Chem. 290 (2015) 15570–15580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.641431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.