Abstract

We evaluated the nationwide trends in paediatric hospitalisations including non-emergency hospitalisations during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Using inpatient data from 272 acute-care hospitals covering 12.4% of total hospitalisations of all ages, we analysed the number of hospitalisations of children (aged 1–17 years) for weeks 9–21 of 2020 (during the outbreak) versus 2017–2019. Hospitalisation decreased during the outbreak by 38.4% (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.69). There were reductions in communicable diseases and trauma, possibly through non-pharmaceutical interventions, but not in appendicitis. This study highlights the potential importance of reallocating paediatric care resources during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, health services research, epidemiology

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected children’s social environments and access to healthcare services worldwide. Studies have reported substantial decreases in paediatric emergency department visits and subsequent hospitalisations.1–3 However, little is known about the nationwide overall trends including non-emergency hospitalisations during the pandemic. We investigated the nationwide changes in the number of paediatric hospitalisations for major conditions during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan.

We used a deidentified inpatient claims database, collected under Diagnosis Procedure Combination/Per-Diem Payment System, built by Medical Data Vision Co. (Tokyo, Japan).4 Briefly, this payment system is part of public health insurance reimbursement system in Japan,5 and therefore, the database consists of demographic/clinical information of all the hospitalisations for each hospital. The database included 272 Japanese acute-care hospitals that consented to data utilisation (covering 12.4% of all admissions into acute-care hospitals in Japan in January 2019). We aggregated the weekly number of hospitalisations of children aged 1–17 years during the calendar weeks 1–21 of 2020 (January 1 to May 26) and the same periods in 2017–2019. We included only patients admitted for ≤30 days (accounting for 99% of the paediatric hospitalisations in our dataset) because our dataset could not observe patients who were hospitalised for more than 30 days from week 21 of 2020.

We described weekly trends in total paediatric hospitalisations and those with a primary diagnosis of one of nine selected conditions, based on the date of admission. We used nine common conditions (determined based on International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision code), including food allergy, acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) except COVID-19, Kawasaki disease (KD), intestinal infectious diseases (IID), febrile convulsions, asthma, appendicitis, inguinal hernia and trauma. We also examined hospitalisations with a primary diagnosis of COVID-19 to illustrate the epidemic in Japan.

We employed a ‘difference in differences’ model using Poisson regression to estimate the changes in the number of hospitalisations during the COVID-19 outbreak. It included a variable for each week, the year indicator (2017–2020) and an interaction variable between the outbreak status (week 9–21; the government requested nationwide cancellation of large-scale events and school closures in week 9 of 2020) and the year indicator for 2020.

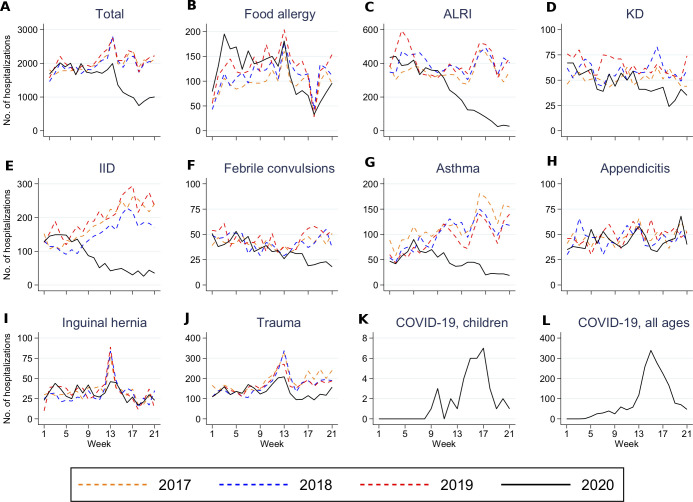

The weekly mean number of paediatric hospitalisations during weeks 9–21 decreased from 2132 in 2017–2019 to 1314 in 2020, a reduction of 38.4% (adjusted incidence rate ratios, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.69) (figure 1 and table 1). The weekly mean number of hospitalisations during weeks 9–21 decreased in 2020 compared with 2017–2019 for food allergy (0.61; 0.52–0.70), for ALRI (0.39; 0.26–0.58), for KD (0.77; 0.67–0.89), for IID (0.22; 0.17–0.29), for febrile convulsions (0.69; 0.57–0.84), for asthma (0.37; 0.29–0.47), for inguinal hernia (0.80; 0.67–0.95) and for trauma (0.68, 0.61–0.75). We found no evidence that the number of hospitalisations for appendicitis decreased (0.96; 0.82–1.12).

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of hospitalisations of children across 272 acute-care hospitals in Japan, overall and by condition during weeks 1–21 in 2017–2020. We illustrated weekly paediatric hospitalisations, overall, and for each common condition across the 272 acute-care hospitals in Japan (A–J). We also showed trends in hospitalisations for COVID-19 among children (K) and all ages (L), using International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision code U071 and B342. B342 was used for reimbursement for COVID-19 hospitalisations before April 2020. ALRI, acute lower respiratory infections; IID, intestinal infectious diseases; KD, Kawasaki disease.

Table 1.

Change in the number of paediatric hospitalisations during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan

| Condition* | No. of hospitalisations per week† | Difference between 2017–2019 and 2020 | Adjusted incidence rate ratio‡ | ||||

| Weeks 9–21 of 2017–2019 | Weeks 9–21 of 2020 | Count | % change | Estimate | 95% CI | P value | |

| Acute lower respiratory infections | 379 | 145 | −235 | −61.9 | 0.39 | 0.26 to 0.58 | <0.001 |

| Intestinal infectious disease | 209 | 49 | −160 | −76.5 | 0.22 | 0.17 to 0.29 | <0.001 |

| Trauma | 199 | 136 | −63 | −31.9 | 0.68 | 0.61 to 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 120 | 36 | −84 | −69.7 | 0.37 | 0.29 to 0.47 | <0.001 |

| Food allergy | 119 | 103 | −16 | −13.1 | 0.61 | 0.52 to 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Kawasaki disease | 58 | 42 | −16 | −27.4 | 0.77 | 0.67 to 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Appendicitis | 49 | 45 | -4 | −8.9 | 0.96 | 0.82 to 1.12 | 0.59 |

| Febrile convulsions | 42 | 28 | −14 | −33.2 | 0.69 | 0.57 to 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Inguinal hernia | 34 | 30 | -4 | −12.2 | 0.80 | 0.67 to 0.95 | 0.01 |

| Total | 2132 | 1314 | −818 | −38.4 | 0.60 | 0.53 to 0.69 | <0.001 |

*International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision codes for the conditions were: A37, B012, B052, B59, B371, J9–J18 and J20–J22 (acute lower respiratory infections), A00–A09 (intestinal infectious diseases), S00–S99 and T00–T14 (trauma), J45 and J46 (asthma), T780 and T781 (food allergy), M303 (Kawasaki disease), K35–K37 (appendicitis), R560 (febrile convulsions) and K40 (inguinal hernia).

†The numbers of hospitalisations were shown as a weekly mean over the corresponding weeks.

‡A Poisson regression was applied to estimate adjusted incidence rate ratio with the weekly and the yearly trends adjusted. Huber-White SEs were used for inference. P<0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant (Stata V.16.1).

There were considerable decreases in paediatric hospitalisations across Japanese acute-care hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak, especially concerning conditions related to communicable diseases and trauma, but not for appendicitis. Our findings may encourage policy-makers to reallocate paediatric care resources during the pandemic. There are several possible explanations for these reductions. First, non-pharmaceutical interventions (physical distancing and individual hygiene measures) probably reduced infections. School closures and stay-at-home requests presumably decreased accidents. Second, deferred/cancelled treatments or examinations may explain the modest decrease in inguinal hernia hospitalisations, especially in week 13 (corresponding to the spring break) of 2020 compared with previous years.

Limitations of this study include the patient population, which did not cover all the Japanese hospitals although our dataset covered 272 acute-care hospitals. Second, the detailed mechanisms through which the paediatric hospitalisations decreased remain unknown.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KS and AM: had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the data and its analyses, drafted the manuscript and did statistical analyses. All authors: study concept and design, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and administrative, technical or material support. AM: study supervision.

Funding: This study was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants (grant number 20K18956 to AM). Medical Data Vision (Tokyo, Japan) provided the dataset used in this study in the form of labour service. AM was supported by the Social Science Research Council Abe Fellowship.

Competing interests: MN is one of the board of directors in Medical Data Vision and received a personal salary from it outside of this study. HN supported Medical Data Vision in algorithm construction and received personal fee outside this study.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics Board of the University of Tokyo approved this study (approval no: 2020105NI).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Due to the contractual restrictions between the authors and the Medical Data Vision, the data are available on request.

References

- 1.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e10–11. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Black BS, et al. Characterizing pediatric emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med 2021;41:201–4. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams TC, MacRae C, Swann O. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe K, Miyawaki A, Nakamura M, et al. Trends in hospitalizations for asthma during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:494–6. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashida K, Murakami G, Matsuda S, et al. History and profile of diagnosis procedure combination (DPC): development of a real data collection system for acute inpatient care in Japan. J Epidemiol 2021;31:1–11. 10.2188/jea.JE20200288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.