Abstract

Objective:

Current racial mental health disparities among African American women have been attributed to chronic experiences of race-related stressors. Increased exposure to racism in predominately White spaces may increase reliance on culturally normative coping mechanisms. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between psychological distress, perceived racial microaggressions, and an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions among educated, middle-class African American women.

Design:

A sample of 243 African American women aged 19–72 years (M = 39.49 years) participated in an online study. Participants completed self-report measures of psychological distress (PHQ-8 and GAD-7), racial microaggressions (IMABI), and modified items from the Stereotypical Roles for Black Women (SRBWS) to assess an obligation to display strength/suppress emotions. Factor analyses were conducted to assess the reliability of the obligation to show strength/suppress emotions subscale in our sample. Descriptive statistics, multiple linear regression, and mediation analyses were also conducted to examine variable associations.

Results:

Statistical analyses revealed educated, middle-class African American women who endorse an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions with perceived racial microaggressions experienced increased psychological distress.

Conclusion:

Obligation to show strength/suppress emotion may increase risk for psychological distress among African American women who perceive racial microaggressions. Future research and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: African American women, middle-class, Superwoman Schema, racial microaggressions, psychological distress

1.0. Introduction

Recent research provides mixed findings regarding the prevalence and rates of mental health symptoms among African American women. For example, scholars suggest African American women have lower odds of every mental health disorder except posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to White women (Erving, Thomas, & Frazier, 2019). On the contrary, other scholars suggest African American women experience poorer psychological outcomes than their White counterparts (Allen et al., 2019). For example, population-based statistics indicate African American women disproportionately report psychological distress such as sadness (5.3% vs. 3.3%), hopelessness (7.1% vs. 5.5%), and worthlessness (4.6% vs. 4.7%) when compared to women of other racial/ethnic groups (CDC, 2019). These conflicting numbers have been attributed to underreporting among African American women due to stigma of appearing weak (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2016).

In addition to race and gender, socioeconomic class can influence African American women’s reports of mental health problems. Higher percentages of mental health concerns are present among women with postsecondary degrees (SAMHSA, 2018). Educational and financial resources do not always absolve mental health concerns among African American women as they encounter societal, career, and cultural pressures to achieve success, which can lead to psychological distress (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Scholars purport one of the reasons African American women report higher psychological distress is their increased exposure to racism in predominantly White spaces (Ashley, 2014; Walton & Boone, 2019; Woods-Giscombé & Lobel, 2008). Yet, middle-class African American women who frequently encounter race-related stressors, such as racial microaggressions, stereotype threat, and tokenism are overlooked in existing research (Allen et al., 2019; Walton & Boone, 2019).

Among middle-class African American women, their intersectional identities of race, gender, and class influences their lived experiences. The Superwoman Schema has been presented as a cultural norm for mitigating stressors associated with their multiple marginalized identities (Abrams, Maxwell, Pope, & Belgrave, 2014; Liao, Wei, & Yin, 2019; Watson-Singleton, 2017; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). However, a recent study suggests endorsement of the Superwoman Schema can produce negative psychological outcomes (Liao, Wei, & Yin, 2019). Limited research has examined the influence of Superwoman Schema on the mental health of African American women when responding to chronic racial microaggressions. Using a culturally specific framework, the purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between perceived racial microaggressions, an obligation to show strength/suppress emotion, and symptoms of psychological distress among a sample of middle-class African American women. Findings from this study will inform recommendations for clinical interventions with this understudied group.

1.1. Racial microaggressions and African American women

Racism continues to plague African Americans despite proclamations of a post-racial society (Bonilla-Silva, 2015). An ideology of presumed superiority of the White race is often perpetuated through individual and institutional-level practices (Golash-Boza, 2016). Microaggressions are examples of individual-level racism and are broadly defined as unintentional, yet derogatory slights directed towards African Americans (Sue, 2010). Racial microaggressions are based upon underlying stereotypes about African Americans such as differences in cultural norms, intelligence, work ethic, and criminality (Lewis, Mendenhall, Harwood, & Huntt, 2016). Gender differences influence how African Americans experience and contend with racial microaggressions. The added burden of racism produces consequences for African American women such that they report disproportionate rates of psychological distress compared to African American men (Donovan, Galban, Grace, Bennett, & Felicie, 2013).

Existing research indicates African American women with higher levels of education and incomes may be particularly at risk for encountering racial microaggressions (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015). African American women are the racial minority in predominantly White professional spaces due to social stratification based on education and SES (West, 2019). Further, given African American women’s continued quest to earn higher education (U.S. Department of Education, 2019) and achieve workplace mobility (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017), it is likely many will continue to encounter predominantly White and racially invalidating spaces. Frequent encounters of racial microaggressions exhaust cognitive resources (Sue, 2010) and often result in psychological distress (Nadal, Griffin, Wong, Hamit, & Rasmus, 2014). However, the unique ways in which middle-class African American women cope with the psychological impact of racial microaggressions may be overshadowed in studies sampling their lower-SES counterparts.

1.2. Racial microaggressions and mental health among African American women

African American women encounter biased racial and gender stereotypes, and subsequent unfair treatment as a function of their intersecting race and gender identities (Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2004). Internalization of such stereotypes can be harmful to one’s mental health (Waldron, 2019). Hence, exposure to racial microaggressions fueled by racism has been positively associated with psychological distress among African American women (Donovan, Galban, Grace, Bennett, & Felicie, 2013; Williams, Kanter & Ching, 2018; Williams & Lewis, 2019). For example, a study examining stressors among African American women found experiencing racial micro- and macroaggressions significantly predicted their depressive and anxiety symptoms (Donovan et al., 2013). Although depression and anxiety tend to be parsed for appropriate diagnosis and treatment planning, they are often indicators of psychological distress that together have a major impact on one’s health (Assari, Dejman, & Neighbors, 2016).

To understand how middle-class African American women combat the effects of racial microaggressions, extant literature has explored coping and resilience strategies among this population (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015; Williams & Lewis, 2019). For example, a sample of educated African American women qualitatively described being “superwoman” as a self-protective strategy against racial microaggressions (Lewis, Mendenhall, Harwood, & Huntt, 2013). Further, African American women who worked in corporate settings noted a need to develop an “armor” of protection to deal with racial microaggressions (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015). Since racism elicits strong emotional reactions, this self-protective shield likely entailed portraying strength and suppressing emotions in response to microaggressions in the workplace. Displaying strength and suppressing emotions are common responses among African American women because they are culturally learned ways to organize, understand, and react to racism in a predominantly White society (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003).

1.3. Superwoman Schema: Cultural framework for coping with racial microaggressions

The conceptualization of African American women’s behavioral and affective responses to perceived racial microaggressions warrants exploration of Beauboeuf-LaFontant’s (2003) research on the culturally defined construct of strength. Historically, the concept of strength was derived in part due to the fortitude exhibited by African American women to withstand the emotional, psychological, and physical atrocities committed against them during slavery (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003). During the post-slavery era, African American women were praised for their strength and ability to assume multiple roles, be the backbone of their respective communities, breadwinner in the household, provide for their families, and ensure family survival (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003).

The construct of strength is interwoven into a culturally valued norm, known as the Superwoman schema (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). The Superwoman schema is operationally defined as an African American woman who constantly suppresses emotion in response to personal stressors to attend to the emotional needs of others and effectively manage multiple roles (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Natural emotional responses such as sadness and worry are perceived as ‘weaknesses’ and threats to individual strength (Collins, 2005). Subsequently, African American women may be more likely to exude strength even during times of extraordinary stress. Incidents of racial microaggressions may be endured with significant poise and pride in an effort to conceal distressing emotions and/or perceived weaknesses.

The ability to show strength and suppress emotions are two commonly endorsed ways African American women manage daily race-related stressors. For instance, Woods-Giscombé (2010) engaged a community-based sample of 48 African American women to assess attitudes about stress, coping strategies, and the concept of strength. The women revealed displaying strength and suppression of emotion were culturally valued ways of concealing strong emotions or signs of ‘weakness.’ Despite these attempts, however, many of the participants endorsed symptoms of depression and anxiety, including: “nervous breakdowns,” feeling overwhelmed, racing thoughts, difficulty concentrating, and hopelessness (Woods-Giscombé, 2010; p. 15). These findings suggest obligations to show strength and suppress emotion may overlap in many ways and may not represent separate constructs. Instead, both constructs are likely to capture an intertwined culturally valued norm associated with ways in which African American women manage multiple roles while simultaneously managing race-related stressors.

The findings from the study also revealed even as a widely endorsed coping strategy, an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions may be psychologically maladaptive for African American women. Scholars have separately examined the deleterious impact of racial microaggressions on the mental health of African American women (Moody & Lewis, 2019; Williams & Lewis, 2019) and poor mental health outcomes resulting from endorsing Superwoman Schema among African American women (Liao, Wei, & Yin, 2019). Our study seeks to bridge this discussion by investigating an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions as a potential mediator between racial microaggressions and psychological distress among highly educated African American women. Although Allen and colleagues (2019) posit displaying strength and suppressing emotions in response to racial discrimination is generally protective for African American women’s physical health, encounters with race-related stressors, particularly in the workplace, have a stronger impact on one’s mental health (Erving, Satcher, & Chen, 2020). We argue endorsing Superwoman Schema while facing pervasive racial microaggressions may explain the high prevalence of psychological distress among this population. Addressing this norm as a mediating variable can provide implications for coping with microaggressions that occur in predominantly White spaces of work, school, and social settings.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Study sample

The sample in the current study consisted of 243 African American women who volunteered to participate in an online study examining health-related outcomes from March to May 2013. Study recruitment procedures included posting advertisements to professional email listings, social media websites, email solicitations to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), and dissemination of fliers on colleges and universities in a southern state. A snowball sampling procedure was also used to encourage participants to refer friends and relatives to participate in the study. Interested participants were asked to complete a 15-minute survey via QuestionPro.com. Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age and self-identified as Black or African American. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and participants were offered an opportunity to enter a drawing to receive one of three $50 Amazon gift cards. Overall, the African American women reported an average age of 39.49 years, a mean of 17.16 years of education (12 years equals a high school diploma or equivalent), no current partner (57%), full-time employment (75%), and a median annual income of approximately $63,000. The women in the sample were considered highly educated because on average, participants had acquired post-baccalaureate/graduate level training or its equivalent. Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Descriptive Sample Characteristics of African American Women (N = 243)

| M | SD | Range | α | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distress | 3.98 | 2.10 | 0.00 – 9.27 | 0.86 | |

| Age (years) | 39.46 | 12.59 | 19.00–72.00 | ||

| Education (years) | 17.14 | 2.92 | 10.00–28.00 | ||

| Partner Status | |||||

| Current Partner (= 1) | 43.3 | ||||

| No Partner (= 0) | |||||

| Employment Status | |||||

| Full-Time | 75.3 | ||||

| Part- Time | 9.9 | ||||

| Unemployed | 6.6 | ||||

| Income (median) | 63,000 | ||||

| Racial Microaggressions | 29.49 | 11.76 | 4.00–64.00 | 0.89 | |

| Obligation to Show Strength/Suppress Emotions | 26.67 | 5.74 | 10.00–40.00 | 0.88 |

2.2. Measures

Control Variables.

The control variables in this study were age, years of education, partner status, and employment status (see Table 5). Participants were asked “How old are you?” to assess age. Years of education were calculated using the following question: “How many years of education have you completed?” The participants were asked, “What is your marital status?” to determine partner status. Partner status was re-coded from 1 = single/never married, 2 = married/cohabitating, and 3 = divorced/separated/widowed to 1 = current partner or 0 = no current partner. The women were prompted to “check one (or more) that apply to you?” and select from the following options: 1 = employed full-time, 2 = employed part-time, or 3 = unemployed/don’t work. Employment was dummy coded whereas full-time employment was the reference category comparing it to part-time and unemployment. Independent variables were perceived racial microaggressions and an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions.

Psychological Distress.

Symptoms of psychological distress were analyzed using items from the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item (PHQ-8; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001; see Table 1) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006; see Table 2). Depressive symptoms were measured with the research version of the PHQ-8 (Kroenke et al., 2001). The questions are based on criteria for major depressive disorder derived from the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000). Participants were asked how often in the last two weeks they were bothered by depressive symptoms. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day. Anxiety symptoms were measured with the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al. 2006). The items are derived from criteria outlined in the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) and used to screen or assess generalized anxiety. Participants were asked how often in the last two weeks they were bothered by anxiety symptoms. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day.

Table 1.

Patient Health Questionnaire, 8-item (PHQ-8; Kroenke, Spitzer & Williams, 2001)

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? |

|---|

| 1. Little interest in doing things. |

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. |

| 3. Trouble falling asleep, staying sleep, or sleeping too much. |

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy. |

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating. |

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself-or that you’re failure or have let yourself or your family down. |

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television. |

| 8. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people have noticed. Or the opposite- being so fidgety or restless you have been moving around a lot more than usual. |

Table 2.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams & Lowe, 2006)

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? |

|---|

| 1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge. |

| 2. Not being able to sleep or control worrying. |

| 3. Worrying too much about different things. |

| 4. Trouble relaxing. |

| 5. Being so restless it is hard to sit still. |

| 6. Becoming easily annoyed or irritable. |

| 7. Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen. |

Items on the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 were moderately positively skewed and transformed to the square root for data analyses (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The results also revealed depressive and anxiety symptoms were correlated (r = .753, p < .001). Thus, depression and anxiety symptoms were combined to create the psychological distress scale. Higher scores of psychological distress suggests comorbid symptoms and impairment associated with major depression and generalized anxiety. The total score ranges from 0 to 9.27 (M = 3.98; SD = 2.10) (see Table 5). The Cronbach’s alpha for the psychological distress scale was 0.86.

Racial Microaggressions.

The Inventory of Microaggressions against Black Individuals (IMABI; Mercer, Zeiger-Hill, Wallace, & Hayes, 2011; see Table 3) consisted of a 14-item instrument to measure the independent variable of experiences of racial microaggressions. Participants were asked in the last year, how often they experienced incidents of racial microaggressions and how much they were upset by the experiences. Sample items include: “I was made to feel that my achievements were primarily due to preferential treatment based on my racial/ethnic background”, “Someone reacted negatively to the way I dress because of my racial/ethnic background”, and “When successful, I felt like people were surprised that someone of my racial/ethnic background could succeed.” Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = this has never happened to me to 4 = this event happened to me and I was extremely upset. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, and summed item responses ranged from 0.00 to 49.00 (M = 15.48, SD = 11.33). Higher scores are indicative of greater distress related to perceived racial microaggressions (see Table 5). The IMABI has been validated through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and item response theory analysis in previous research (Mercer, Zeiger-Hill, Wallace, & Hayes, 2011).

Table 3.

Inventory of Microaggressions against Black Individuals (IMABI; Mercer, Zeiger-Hill, Wallace, & Hayes, 2011)

| 1. I was made to feel that my achievements were primarily due to preferential treatment based on my racial/ethnic background. |

| 2. I was treated like I was of inferior status because of my racial/ethnic background. |

| 3. I was treated as if I was a potential criminal because of my racial/ethnic background. |

| 4. I was made to feel as if the cultural values of another race/ethnic group were better than my own. |

| 5. Someone told me that I am not like other people of my racial/ethnic background. |

| 6. Someone made a statement to me that they are not racist or prejudiced because they have friends from different racial/ethnic backgrounds. |

| 7. I was made to feel like I was talking too much about my racial/ethnic background. |

| 8. When successful, I felt like people were surprised that someone of my racial/ethnic background could succeed. |

| 9. Someone assumed I was a service worker or laborer because of my race/ethnicity. |

| 10. I was followed in a store due to my race/ethnicity. |

| 11. Someone reacted negatively to the way I dress because of my racial/ethnic background. |

| 12. Someone asked my opinion as a representative of my race/ethnicity. |

| 13. Someone told me that they are not racist or prejudiced even though their behavior suggests that they might be. |

| 14. Someone told me that everyone can get ahead if they work hard when I described a difficulty related to my racial/ethnic background. |

Obligation to Show Strength/Suppress Emotions.

Participants were administered items from the Stereotypic Roles for Black Women Scale (SRBWS; Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2004) that were modified based on the Superwoman Schema conceptual framework (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). For example, an item from the SRBWS, “I tell others that I am fine when I am depressed or down” was modified to “I tell others that I am fine when I am depressed or anxious” (see Table 4). A principal component analysis (PCA) and varimax rotation (DeVellis, 2012) were conducted to determine latent variables associated with Superwoman schema and identify clusters of items consistent with the hypothesized construct, obligation to show strength and suppress emotions.

Table 4.

Obligation to Show Strength/Suppress Emotion Subscale, 10-item Questionnaire.

| Factor Loadings | |

|---|---|

| 1. I find it difficult to ask others for help. | .633 |

| 2. It is difficult for me to tell other people my problems. | .607 |

| 3. I do not want others to know if I experience a problem. | .564 |

| 4. I do not expect nurturing from others. | .601 |

| 5. I feel that I need to push my emotions down. | .586 |

| 6. I tell others that I am fine when I am depressed or anxious. | .593 |

| 7. It is difficult for me to share problems with others. | .608 |

| 8. I cannot let others see me cry. | .640 |

| 9. It is difficult for me to turn to others when I need help. | .706 |

| 10. When I have limited resources (ex. Money, friends, food), I am willing to ask others for help.* | .648 |

reverse coded.

A recent study examining the psychometrics of the SWS revealed the questionnaire contained five subscales. Obligation to show strength (α=.70) and suppress emotions (α=.85) loaded onto separate constructs (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2019). In the current study, a factor analyses revealed 10 items theoretically consistent with obligation to show strength and suppress emotions overlap among our sample of higher educated African American women (Table 4). A subscale hereinafter referenced as obligation to show strength/suppress emotions was created. Participants were asked to rate agreement with attitudes African American women hold about themselves and their environment. Other sample items include: “I find it difficult to ask others for help,” “I feel that I need to push my emotions down”, and “I cannot let others see me cry.” Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly agree to 4 = strongly disagree. Internal consistency of the items was assessed using reliability analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88, and summed item responses ranged 10.00 to 40.00 (M = 26.67, SD = 5.74). Negatively worded items were reverse scored. Higher scores indicate greater identification with an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the associations between continuous variables. Point-biserial correlation coefficients were calculated to examine associations between dichotomous and continuous variables. The control and independent variables significantly correlated with the dependent variables at the bivariate level were retained for further analyses. Linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the proportion of variance racial microaggressions and obligation to show strength/suppress emotions accounted for while measuring psychological distress. Control variables significant at the bivariate level were entered first, perceived racial microaggressions were entered second, and obligation to show strength/suppress emotions were entered third. Variables significant at the p level of ≤ .05 were displayed at each step and interpreted in the final model. Tolerance and variance inflation statistics did not indicate multicollinearity among the study variables. List-wise deletion was used to account for missing data, resulting in a final sample of 227 participants.

To analyze potential mediation effects, the bootstrap method (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) was utilized to estimate indirect effects of an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions as a mediator between racial microaggressions and psychological distress. The bootstrapping method has been deemed more powerful than the three-step multiple regression approach (Baron & Kenny, 1986) and Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). Mediation analyses with bootstrap estimates based on the recommended 5,000 resamples were performed using PROCESS macro v3.3 (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013) in SPSS 26.0.

3.0. Results

The principal component and varimax rotation analyses revealed 10 modified items from the SRBWS loaded onto a single construct. The items theoretically represent obligation to show strength and suppress emotions as qualitatively discussed in prior research (e.g. Woods-Giscombé, 2010). The subscale descriptives (M = 2.66, range: 2.52 – 2.86). Initial bivariate correlations (see Table 6) revealed the hypothesized independent variables of racial microaggressions and an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions were positively and significantly correlated with psychological distress. Age was negatively and significantly associated with psychological distress. Neither years of education, partner status, nor employment status were significantly associated with psychological distress. Subsequently, these variables were not included in further analyses.

Table 6.

Correlates of Psychological Distress among African American Women (n = 231)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Psychological Distress | - | ||||||

| 2) Age | −.24** | - | |||||

| 3) Education | −.11 | −.02 | - | ||||

| 4) Partner Statusa | −.12 | −.25** | .03 | - | |||

| 5) Employment | −.09 | −.18** | .01 | −.01 | - | ||

| 6) Obligation to Strength/Suppress Emotions | .50** | −.19** | −.11 | −.10 | −.04 | −.03 | - |

| 7) Racial Microaggressions | .24** | −.10 | −.06 | −.18** | .05 | .14* | −.23** |

The multivariate analyses examining the relationship between demographic factors, independent variables, and psychological distress are displayed in Table 7. The final model was significant, F (3, 227) = 33.09, p < .001, and accounted for 30.7% of the total variance in symptoms of psychological distress. Age was a significant negative correlate of psychological distress in the first model (β = −0.24, p = .000). Older women in the sample endorsed fewer symptoms of psychological distress. In the second model, age remained a significant negative correlate and perceived racial microaggressions (β = 0.24, p = .000) emerged as a significant positive correlate of psychological distress. Participants who perceived more racial microaggressions endorsed greater symptoms of psychological distress. In the third model, age remained a significant negative correlate (p < .01) and perceived racial microaggressions remained a significant positive correlate (p < .05). Obligation to show strength/suppress emotion (β = 0.45, p = .000) was a significant positive correlate of psychological distress and accounted for 17% of the total variance. African American women who endorsed a greater obligation to show strength/suppress emotion endorsed more psychological distress (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Summary of Hierarchical Linear Regression Examining Correlates of Psychological Distress among African American women (n = 227)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Age | − 0.04 (0.01)*** | −.24 | − 0.03(.01)*** | − 0.22 | −0.02 (.01)** | − 0.16 |

| Racial Microaggressions | 0.04 (.01)*** | 0.24 | 0.02 (.00)* | 0.13 | ||

| Obligation to show Strength and Suppress Emotions | 0.16 (.02)*** | 0.45 | ||||

| R2 | .05*** | .11*** | .29*** | |||

| ΔR2 | .12*** | .30*** | ||||

p <.05;

p < .01;

p ≤ .001

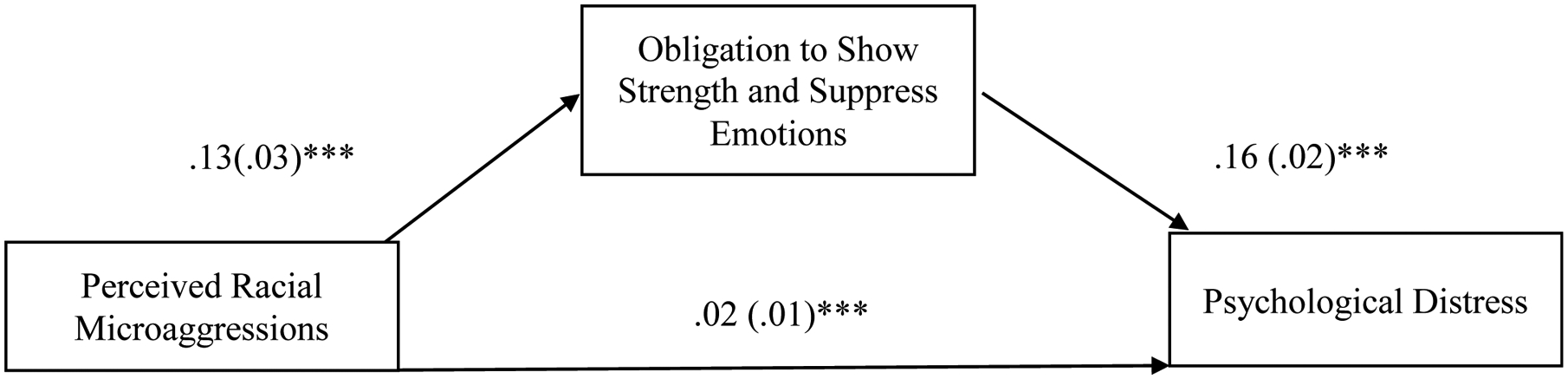

In the mediation model (see Figure 1), age was treated as a covariate to control for its influence on the estimates of the direct and indirect effects. First, there was a positive association between racial microaggressions and psychological distress (B = .02, SE = .01, 95% CI [.0013, .0470]). Second, there was a positive association between an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions and racial microaggressions (B = .13, SE = .03, 95% CI [.0641, .1919]). Third, there was a positive significant association between an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions and psychological distress (B = .16, SE = .02, 95% CI [.1138, .1978]). Last, an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions emerged as a significant mediator between racial microaggressions and psychological distress. The demonstrated bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect did not contain zero (c’ = .02, SE = .0053, 95% CI [.0103, .0309], see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mediation Model: Obligation to Show Strength Suppress Emotions

* p <.05; ** p < .01; *** p ≤ .001

4.0. Discussion

The current study examined how an obligation to show strength/suppress emotion, a norm associated with the Superwoman Schema, contributes to negative mental health outcomes among middle-class African American women who experience racial microaggressions. This group of women remain an underrepresented and understudied population in existing literature because research has focused primarily on less educated and lower income African American women (Woods-Giscombé, Robinson, Carthon, Devane-Johnson, & Corbie-Smith, 2016). The results demonstrated racial microaggressions and an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions were positively significant correlates of psychological distress. Age was a negatively significant correlate of psychological distress. Mediation analyses further indicated middle-class African American women who endorse an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions when encountering racial microaggressions experience more psychological distress. This finding extends prior scholarship by positing a culturally-endorsed coping strategy of showing strength/suppressing emotion may be an initial protective asset that becomes a psychological liability when overused (Watson & Hunter, 2016).

Our findings revealed older African American women in our sample reported less psychological distress. Further, older women reported less endorsement of an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions. Older middle-class African American women may be less likely to be involved in the workforce due to retirement, thereby buffering them from a significant source of racial microaggressions (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015). However, younger African American women often encounter racial microaggressions in addition to experiencing daily intimidation and sexual harassment in the workplace (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015). Those who experience racial microaggressions and endorse the Superwoman schema are at an especially high risk for mental health problems (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2018). Psychological distress is consequently associated with poor work productivity, physical health problems, and decreased lifespan (Greenberg, Fournier, Sisitsky, Pike, & Kessler, 2015).

The results of this study align with previous research which argued endorsement of the Superwoman schema results in high rates of psychological distress (Abrams, Hill, & Maxwell, 2019; Watson & Hunter, 2016). Abrams and colleagues (2019) suggest self-silencing behaviors such as presenting an image of strength and emotional suppression are associated with depressive symptoms among African American women. African American women may engage in these behaviors to fulfill expectations of taking care of others and managing multiple responsibilities simultaneously. Interestingly, many African American women take pride in showing strength and suppressing distressful emotions. This tendency can be temporarily adaptive and is often culturally rewarded (Abrams, Maxwell, Pope, & Belgrave, 2014).

Long-standing cultural norms of strength and emotional suppression may be an impediment towards help-seeking among African American women (Watson & Hunter, 2016). Research suggests African American women who feel an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions are more likely to report less perceived emotional support from others (Watson-Singleton, 2017). Further, an obligation to help others and deprioritize one’s own health is another cultural script for African American women who endorse Superwoman Schema (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2019). Untreated mental health concerns further widen health disparities and increases the likelihood of suicidal ideation among African Americans due to feeling burdensome (Hollingsworth et al., 2017). The number of suicides among younger African Americans has increased significantly in the past decade (Price & Khubchandani, 2019), which raises concern for African American women who suppress emotions and avoid seeking support when experiencing distress (Oh, Waldman, Koyanagi, Anderson, & DeVylder, 2020).

Of interest, the association between perceived racial microaggressions and psychological distress was mediated by an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions. In other words, the absence of active coping strategies, through an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions, results in psychological distress (Williams, Kanter, & Ching, 2018). Recent literature suggests disengagement coping increases depressive symptoms among African American women who report gendered racial microaggressions (Williams & Lewis, 2019). Our study confirms this finding and demonstrates showing strength/suppressing emotions may be a way in which middle-class African American women experience race-related psychological distress. Active coping strategies including social support, assertiveness, physical activity, and seeking professional counseling may be beneficial in managing chronic and often unavoidable experiences of racial microaggressions (Holder, Jackson, & Ponterotto, 2015). The development of active coping strategies may alter the deleterious impact of racial microaggressions and reduce psychological distress among middle-class African American women.

4.1. Implications

Given their increased socioeconomic mobility (Department of Education, 2019), it is vital to discuss implications specific to middle-class African American women who encounter racial microaggressions and subsequently experience psychological distress. African American women who endorse an obligation to show strength/suppress emotions may be less likely to seek help from others, due to belief it would undermine perceptions of strength, survival, and self-esteem (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2016). This population may not seek professional help until their mental health concerns have reached a crisis such as an emotional breakdown or manifestation of physical health problems. Therefore, informal resources that have been shown to mitigate psychological distress such as faith-based services and sister circles can assist African American women in practicing vulnerability and receiving emotional support in the face of race-related stressors (Abrams, Hill, & Maxwell, 2019).

Some African American women with greater education and high incomes may also be less likely to seek professional help despite increased access to mental health care services and resources (Alang, 2019). There is concern about the availability of culturally competent mental health practitioners (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2016) as many African American women encounter racial microaggressions within therapy (Owen, Tao, Imel, Wampold, & Rodolfa, 2014). To reduce the occurrence of racial microaggressions perpetuated in clinical practice, developing trainings tailored for addressing racial microaggressions within the therapeutic context with African American women is imperative. Our findings can inform culturally tailored clinical interventions with this group (Woods-Giscombé et al., 2016).

An important feature of culturally-competent mental health care is to validate the experiences of racially marginalized populations, who face obstacles of invisibility and ostracization (Ahmed, Wilson, Henriksen Jr., & Jones, 2011). An obligation to show strength/suppress emotions may manifest in therapy as African American women embody caregiver and fixer roles (Watson-Singleton, 2017). Thus, it is important to acknowledge when African American women show strength/suppress emotions as a function of Superwoman Schema in treatment. Utilizing terminology that appropriately labels and normalizes one’s experience has the potential to decrease psychological distress (Nadal et al., 2014). Further, acknowledging the experiences of African American women can cultivate space to express emotions such as anger, hurt, and sadness without reinforcing stereotypes such as the Angry Black Woman (Ashley, 2014). Additionally, fostering self-esteem and self-efficacy through empowerment can be protective of the mental health consequences of racism (Erving, Satcher, & Chen, 2020). Mental health practitioners working with this population have a unique opportunity to discuss how cultural norms such as the Superwoman Schema is one, but not the only, coping strategy African American women can utilize when responding to racial microaggressions.

5.0. Limitations

The current study has limitations. First, data was collected via an online survey, which may hinder the generalizability of our results to all African American women. Second, given the timing of data collection in 2013, the IMABI was available to measure perceived racial microaggressions. In 2015, the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale (GRMS) was developed and validated to assess gendered racial microaggressions among African American women. This measure should be utilized in future research with this population to better capture their gendered-racial experiences. Third, geographic location is an important consideration in examining SES. However, participants were not asked about their geographic locations. Future studies may benefit from inquiring about geographic location when studying demographic correlates of mental health among middle-class African American women.

Employment status was assessed using a forced choice item and may have posed limited options for students and self-employed women. Additionally, partner status was calculated using a single item. As operationalized, the question may not adequately capture a range of partner statuses (e.g. unmarried but dating). Identification with the Superwoman ideology is associated with caretaking roles (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). However, neither parental status nor responsibilities were assessed in the current study. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest middle-class African American women rely on culturally specific coping strategies to respond to racial microaggressions but often at the expense of their mental health. To avoid presenting all middle-class African American women as monolithic, exploring within-group differences of mental health symptoms among this group based on education level, income, and occupation can also inform future research.

6.0. Conclusion

In summary, the current investigation provides insight into the mechanisms through which middle-class African American women experience psychological distress when encountering racial microaggressions in predominately White settings. The culturally relevant coping strategy of displaying strength/suppressing emotions produces only temporary benefits that eventually leads to adverse effects on mental health. Prevention and intervention efforts such as increasing access to culturally competent mental health care and encouraging use of active coping strategies can buffer the effects of racial microaggressions. Despite the pervasiveness of racism, middle-class African American women can benefit from utilizing a variety of tools to manage and reduce their race-related psychological distress.

References

- Abrams JA, Hill A, & Maxwell M (2019). Underneath the mask of the Strong Black Woman Schema: Disentangling influences of strength and self-silencing on depressive symptoms among US Black women. Sex Roles, 80(9–10), 517–526. doi: 10.1007/s11199-018-0956-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, & Belgrave FZ (2014). Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the “Strong Black Woman” schema. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(4), 503–518. doi: 10.1177/0361684314541418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Wilson KB, Henrikson RC Jr, & Jones JW (2011). What does it mean to be a culturally-competent counselor?. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 3(1), 17–28. Retrieved from https://openjournals.bsu.edu/jsacp/article/view/329 [Google Scholar]

- Alang SM (2019). Mental health care among Blacks in America: Confronting racism and constructing solutions. Health Services Research, 54(2), 346–355. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM, Wang Y, Chae DH, Price MM, Powell W, Steed TC, … & Woods-Giscombé CL (2019). Racial discrimination, the superwoman schema, and allostatic load: exploring an integrative stress-coping model among African American women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1457(1), 104–127. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley W (2014). The angry Black woman: The impact of pejorative stereotypes on psychotherapy with Black women. Social Work in Public Health, 29(1), 27–34. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2011.619449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Lapeyrouse L, & Neighbors H (2018). Income and self-rated mental health: Diminished returns for high income Black Americans. Behavioral Sciences, 8(5), 50. doi: 10.3390/bs8050050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Dejman M, & Neighbors HW (2016). Ethnic differences in separate and additive effects of anxiety and depression on self-rated mental health among Blacks. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3(3), 423–430. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0154-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T (2003). Strong and large Black women? Exploring relationships between deviant womanhood and weight. Gender & Society, 17(1), 111–121. doi: 10.1177/0891243202238981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(11), 1358–1376. doi: 10.1177/0002764215586826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2017/home.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey: 2018. Tables A-7 and A-8. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm

- Collins PH (2005). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York, NY: Routledge. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, Galban DJ, Grace RK, Bennett JK, & Felicié SZ (2013). Impact of racial macro-and microaggressions in Black women’s lives: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Black Psychology, 39(2), 185–196. doi: 10.1177/0095798412443259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erving CL, Satcher LA, & Chen Y (2020). Psychologically resilient, but physically vulnerable? Exploring the psychosocial determinants of African American women’s mental and physical health. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2332649219900284. doi: 10.1177/2332649219900284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erving CL, Thomas CS, & Frazier C (2019). Is the black-White mental health paradox consistent across gender and psychiatric disorders? American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(2), 314–322. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza T (2016). A critical and comprehensive sociological theory of race and racism. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2(2), 129–141. doi: 10.1177/2332649216632242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, & Kessler RC (2015). The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(2), 155–162. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Scharkow M (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder AMB, Jackson MA, & Ponterotto JG (2015). Racial microaggression experiences and coping strategies of Black women in corporate leadership. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2), 164–180. doi: 10.1037/qup0000024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth DW, Cole AB, O’Keefe VM, Tucker RP, Story CR, & Wingate LR (2017). Experiencing racial microaggressions influences suicide ideation through perceived burdensomeness in African Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 104–111. doi: 10.1037/cou0000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.15251497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Mendenhall R, Harwood SA, & Browne Huntt M (2016). “Ain’t I a woman?” Perceived gendered racial microaggressions experienced by Black women. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 758–780. doi: 10.1177/0011000016641193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, & Neville HA (2015). Construction and initial validation of the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Black women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 289–302. doi: 10.1037/cou0000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KYH, Wei M, & Yin M (2019). The misunderstood schema of the strong Black woman: Exploring its mental health consequences and coping responses among African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 0361684319883198. doi: 10.1177/0361684319883198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SH, Zeigler-Hill V, Wallace M, & Hayes DM (2011). Development and initial validation of the Inventory of Microaggressions Against Black Individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 457–469. doi: 10.1037/a0024937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody AT, & Lewis JA (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and traumatic stress symptoms among Black women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(2), 201–214. doi: 10.1177/0361684319828288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, & Rasmus M (2014). The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 57–66. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00130.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter AM, Michaels EK, Thomas MD, Reeves AN, Thorpe RJ Jr, & LaVeist TA (2018). Relative roles of race versus socioeconomic position in studies of health inequalities: A matter of interpretation. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 169–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Waldman K, Koyanagi A, Anderson R, & DeVylder J (2020). Major discriminatory events and suicidal thoughts and behaviors amongst Black Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Tao KW, Imel ZE, Wampold BE, & Rodolfa E (2014). Addressing racial and ethnic microaggressions in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 283–290. doi: 10.1037/a0037420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JH, & Khubchandani J (2019). The changing characteristics of African-American adolescent suicides, 2001–2017. Journal of Community Health, 44(4), 756–763. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00678-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural models. In Leinhardt S (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, & Löwe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18–5068, NSDUH Series H-53). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, & Ullman JB (2007). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5). Boston, MA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, & Speight SL (2004). Toward the development of the stereotypic roles for Black women scale. Journal of Black Psychology, 30(3), 426–442. doi: 10.1177/0095798404266061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2019). The Condition of Education 2019. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594978.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Waldron IRG (2019) Archetypes of Black womanhood: Implications for mental health, coping, and help-seeking. In Zangeneh M, Al-Krenawi A (Eds.) Culture, Diversity and Mental Health - Enhancing Clinical Practice. Advances in Mental Health and Addiction. Springer, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-26437-6_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton QL, & Boone C (2019). Voices unheard: An intersectional approach to understanding depression among middle-class Black women. Women & Therapy, 42(3–4), 301–319. doi: 10.1080/02703149.2019.1622910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson-Singleton NN (2017). Strong Black woman schema and psychological distress: The mediating role of perceived emotional support. Journal of Black Psychology, 43(8), 778–788. doi: 10.1177/0095798417732414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NN, & Hunter CD (2016). “I had to be strong”: Tensions in the strong black woman schema. Journal of Black Psychology, 42(5), 424–452. doi: 10.1177/0095798415597093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West NM (2019). By us, for us: The impact of a professional counterspace on African American women in student affairs. The Journal of Negro Education, 88(2), 159–180. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.88.2.0159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MG, & Lewis JA (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and depressive symptoms among Black women: A moderated mediation model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), 368–380. doi: 10.1177/0361684319832511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Kanter JW, & Ching TH (2018). Anxiety, stress, and trauma symptoms in African Americans: Negative affectivity does not explain the relationship between microaggressions and psychopathology. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(5), 919–927. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0440-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL, Allen AM, Black AR, Steed TC, Li Y, & Lackey C (2019). The Giscombé superwoman schema questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associations with mental health and health behaviors in African American women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(8), 1–10. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2019.1584654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé C, Robinson MN, Cathon D, Devane-Johnson S, & Corbie-Smith G (2016). Superwoman schema, stigma, spirituality, and culturally sensitive providers: Factors influencing African American women’s use of mental health services. Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions Diversity: Education, Research, & Policy, 9(1), 1124–1144. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26554242 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research, 20(5), 668–683. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]