Abstract

Objective

To define the association between oral and systemic manifestations of Sjӧgren’s syndrome (SS) and quality of life.

Methods

We analyzed a cross-sectional survey conducted by the Sjӧgren’s Foundation in 2016, with 2961 eligible responses. We defined oral symptom and sign exposures as parotid gland swelling, dry mouth, mouth ulcers/sores, oral candidiasis, trouble speaking, choking or dysphagia, sialolithiasis or gland infection, and dental caries. Systemic exposures included interstitial lung disease, purpura/petechiae/cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis, neuropathy, leukopenia, interstitial nephritis, renal tubular acidosis, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, or lymphoma. Outcomes included SS-specific quality of life questions generated by SS experts and patients.

Results

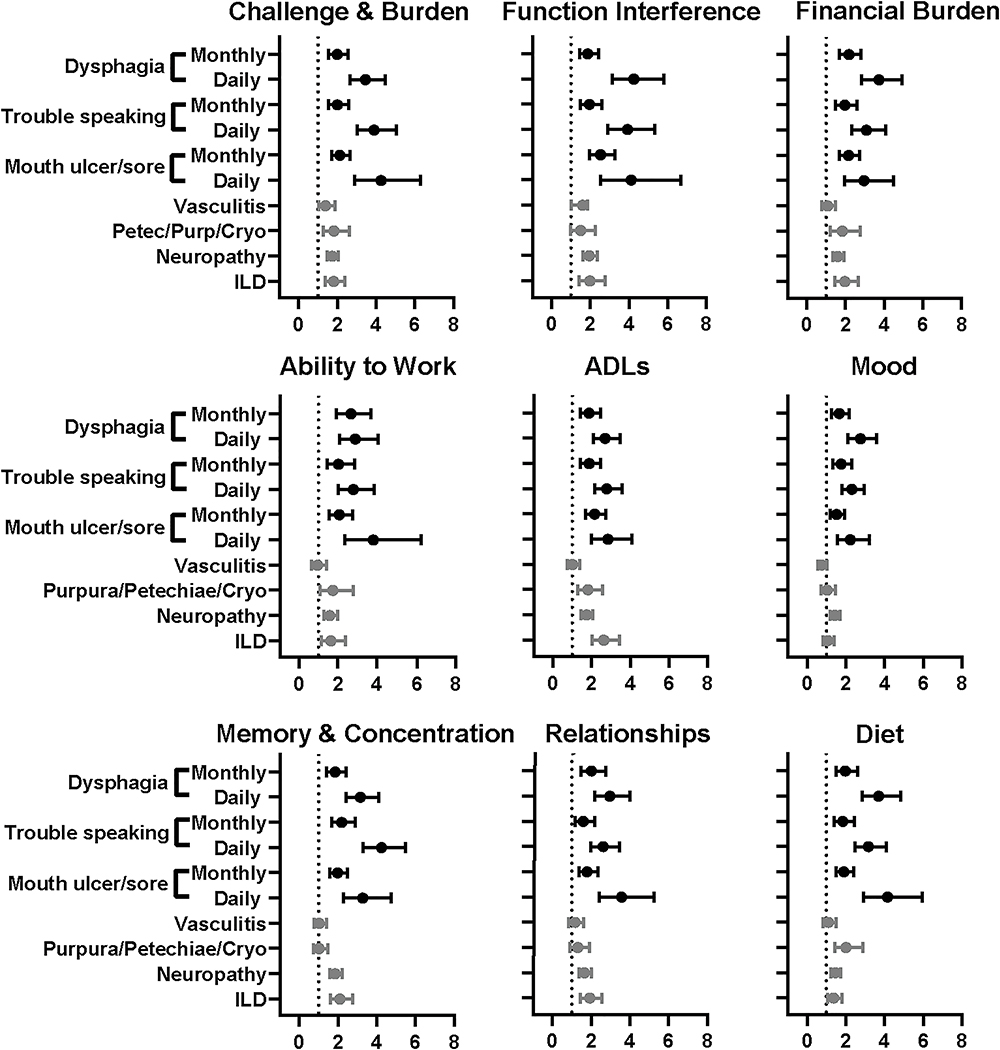

Using multivariable regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, and employment, we observed that mouth ulcers or sores, trouble speaking, and dysphagia were associated with poor quality of life. The following oral aspects had the greatest impact on these following quality of life areas: i) mouth ulcers/sores on the challenge and burden of living with SS (odds ratio [OR] 4.26, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.89–5.48), ii) trouble speaking on memory and concentration (OR 4.24, 95% CI 3.28–5.48), and iii) dysphagia on functional interference (OR 4.25, 95% CI 3.13–5.79). In contrast, systemic manifestations were associated with quality of life to a lesser extent or not at all.

Conclusions

Oral manifestations of SS, particularly mouth ulcers or sores, trouble speaking, and dysphagia, were strongly associated with worse quality of life. Further study and targeted treatment of these oral manifestations provides the opportunity to improve quality of life in patients with SS.

Keywords: Sjӧgren’s syndrome, Quality of life, Oral health

Introduction

Sjӧgren’s syndrome (SS) characteristically presents with ocular and oral dryness, but can affect many organ systems. SS-related morbidity includes impaired quality of life (QoL) stemming largely from pain, dryness, fatigue, and depression.(1–4) SS is associated with increased unemployment and health care costs, both to the patient and the healthcare system.(1–4)

Oral dryness, a hallmark of SS, is associated with poorer oral health-related QoL (OHRQoL) and health-related QOL (HRQoL).(5–11) Previous studies evaluating OHRQoL in patients with SS used quality metrics, such as the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) or Xerostomia-Related Quality of Life Scale (XeQoLS), derived from dental and radiotherapy patients, respectively.(5, 8, 10, 12, 13) However, oral health metrics might have lower sensitivity to detect impaired OHRQoL in SS compared with etiologies of oral dryness such as radiotherapy.(14) Furthermore, OHRQoL metrics are designed to evaluate general oral conditions and QoL, not specific manifestations that are common in SS, such as oral ulcers, glandular swelling, and oral candidiasis, which might point to specific high yield interventions. Thereby, in collaboration with patients and clinicians, the Sjӧgren’s Foundation created a survey of 25 items to assess SS-specific symptom impact and severity.

The objective of this study was to determine the impact of oral dryness, other specific oral manifestations, and systemic involvement on QoL among patients with SS, using a self-reported survey designed by patients with SS as well as SS experts. To our knowledge, this survey and the study presented herein are the largest to date examining a broad range of SS-specific oral manifestations and QoL among respondents with SS.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional survey evaluated the association between symptoms, signs, and systemic disease involvement of SS and patient QoL. Harris Poll® (a social science market research company with public health research experience), the Sjӧgren’s Foundation, and SS patient and provider committees designed the survey.(15) The SS patient and provider committee responsible for development of the questionnaire was composed of 10 volunteers, including physicians with expertise in SS. The survey (included as supplemental information) included seven sections (patient profile, severity, emotional and physical well-being, QoL, treatment, cost of the disease, and demographic information). The Sjӧgren’s Foundation disseminated the survey in 2016 through postal mail. The Foundation’s database was used to identify adult (≥18 year old) patients in the United States who reported receiving a diagnosis of SS by a medical professional. Patients were excluded if they did not report age or biologic sex. The survey was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (IRB) (WIRB 20160808 #14329711). All participants provided written informed consent to analyze and publish the material.

Exposures (Oral symptoms and signs and systemic involvement)

We considered eight of the survey symptoms or signs to be oral manifestations: parotid gland swelling, dry mouth, mouth ulcers/sores, oral candidiasis, trouble speaking, choking or dysphagia, sialolithiasis or gland infection, and dental caries. Response options for each oral manifestation were reported using a frequency scale: never, few times per year, monthly, weekly, and daily. We classified a given symptom or sign as being present if the respondent indicated that it occurred at least monthly.

Participants were asked to select whether they had been diagnosed with systemic manifestations by a healthcare provider. We defined systemic involvement as the patient’s report of the following health conditions diagnosed by a health care provider: lung disease (e.g. interstitial lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, etc)(ILD), purpura/petechiae/cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis, neuropathy, low white blood cells/leukopenia, interstitial nephritis, renal tubular acidosis (RTA), chronic active autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis/primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), or lymphoma.

Outcomes (Quality of life)

A total of 25 items pertaining to QoL was included in the survey. For the purpose of this study, we excluded QoL items that were clearly not related to oral symptoms (four items), had opposite directionality and meaning to other items (three items), or with too few responses to support meaningful analysis (<80% of respondents; four items). We created composites of items a priori by adding individual items that had similar content and a correlation coefficient >0.6 (See Appendix 1 correlation matrix). We reduced our analysis to the following nine outcomes and reported each alone or as a composite of items from the survey.

Challenge and burden – a composite of i) “Living with Sjӧgren’s makes every day a challenge”, ii) “I struggle to cope with my Sjӧgren’s”, and iii) “Living with Sjӧgren’s adds a significant emotional burden to my life”;

Functional interference (“My Sjӧgren’s gets in the way of things I need to do each day”);

Financial burden (“Living with Sjӧgren’s adds a significant financial burden to my life”);

Ability to work (“Job/career or ability to work”);

Activities of daily living (ADLs) (“Performing activities of daily living [e.g., dressing, cooking, cleaning]”);

Mood (“Overall mood”);

Memory & concentration – a composite of i) “Remembering details at home or work”, ii) “Concentrating on a task”, iii) “Concentrating on more than one task at a time” and iv) “Finding the correct word during conversations”;

Relationships (“Relationships with friends and family”); and

Diet (“Making adjustments to diet”).

We defined QoL items (outcomes) as present if respondents selected “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” or if they indicated experiencing “a lot of negative impact” or “a great deal of negative impact.” For questions combined into a composite score, outcome variables were considered present based on the median count distribution. For example, within the composite of challenge and burden, the median score was 10 (527 respondents had a score ≥10). Thus, a score ≥10 was defined as present.

Statistical Analysis

We performed multivariable logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between oral symptoms or signs and systemic involvement (exposures) and QoL (outcome). Because the survey determined SS diagnosis based on respondent self-report, we performed a sensitivity analysis that analyzed only the respondents reporting treatment with hydroxychloroquine, a disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD), or biologic therapy. We calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients comparing each QoL item. Analyses were performed using JMP Pro statistical software version 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

In total, 9,252 surveys were distributed by postal mail and 3,072 (33%) completed surveys were received. We excluded 111 respondents: 41 had reported ages <18 years, 68 did not specify receiving a diagnosis of SS from a health care professional, and two returned incomplete surveys without response to key items of interest. The 2,961 included survey respondents averaged 65.1 years of age and were predominantly white (93%) and female (96%) (Table 1). Among the eight oral manifestations, most respondents had (defined as at least monthly) dry mouth (95%), followed by dysphagia (56%), and many reported trouble speaking (46%) and mouth ulcers/sores (39%) (Table 2). Fewer reported episodic signs such as tooth decay, parotid swelling, yeast infection, and salivary gland stones/infection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the SSF survey cohort (n=2961)

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 65.1 (±11.7) | |

| Age (group) | 18–39 | 79 (3) |

| 40–59 | 783 (26) | |

| 60–79 | 1800 (61) | |

| 80+ | 299 (10) | |

| Sex | Female | 2831 (96) |

| Caucasian Race | 2735 (93) | |

| Employment | Full-time | 569 (20) |

| Part-time | 178 (6) | |

| Self-employed | 128 (5) | |

| Not employed | 407 (14) | |

| Retired | 1398 (50) | |

| Student | 11(0.4) | |

| Stay-at-home | 111 (4) | |

| Missing | 159 (5) | |

| Other Diagnosis | RA | 611 (21) |

| MCTD | 378 (13) | |

| SLE | 291 (10) | |

| SSc | 81 (3) | |

RA=Rheumatoid Arthritis, MCTD=Mixed Connective Tissue Disease,

SLE=Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, SSc=Systemic Sclerosis

Table 2.

Frequency of Oral Manifestations (n=2961)

| Oral Manifestation | Never | Few per Year | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Dry mouth | 46 (2) | 56 (2) | 85 (3) | 234 (8) | 2500 (84) | 40 (1) |

| Dysphagia | 721 (24) | 544 (18) | 502 (17) | 611 (21) | 532 (18) | 81 (3) |

| Trouble speaking | 1072 (36) | 455 (15) | 348 (12) | 527 (18) | 478 (16) | 81 (3) |

| Mouth ulcers/sores | 913 (31) | 811 (27) | 617 (21) | 344 (12) | 189 (6) | 87 (3) |

| Tooth decay | 1100 (37) | 1110 (38) | 210 (7) | 87 (3) | 340 (12) | 114 (4) |

| Parotid swelling | 1723 (58) | 559 (19) | 238 (8) | 146 (5) | 140 (5) | 155 (3) |

| Yeast infection | 2122 (72) | 502 (17) | 137 (5) | 45 (2) | 72 (2) | 83 (3) |

| Salivary gland stones/infection | 2427 (82) | 326 (11) | 58 (2) | 20(1) | 30(1) | 100 (3) |

Eighty-four percent of respondents had at least once (“ever”) used oral comfort agents (e.g., gels, rinses, sprays), 67% prescription or over-the-counter fluoride dental products, 61% saliva substitutes, and 59% secretagogues (Table 3). Fewer than half currently used saliva substitutes, fluoride, or prescription secretagogue treatments. Of the total respondents, 71% had at least once used hydroxychloroquine, 68% DMARDs (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, leflunomide, or sulfasalazine), and 20% biologic therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of Medication Use (n=2961)

| Medication Use | Ever | Prevalence | Current | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Oral Comfort Agents | 2475 | 84 | 1875 | 63 |

| Fluoride Dental Product | 1995 | 67 | 1462 | 50 |

| Saliva Substitutes | 1811 | 61 | 1032 | 35 |

| Secretagogues | 1757 | 59 | 1059 | 36 |

| Chlorhexidine/Non-Fluoride Remineralizing | 1172 | 40 | 556 | 20 |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) alone | 2095 | 71 | 1262 | 43 |

| DMARDs* | 1998 | 68 | 1312 | 44 |

| Biologic tderapy | 590 | 20 | 172 | 6 |

DMARDs=hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, etc.

Oral Symptoms

Of the eight oral symptoms evaluated, mouth ulcers or sores, trouble speaking, and dysphagia were generally associated with worse QoL in all domains in a significant, dose-dependent manner (Figure 1). In terms of magnitude, mouth ulcers or sores were most strongly associated with the challenge and burden outcome (OR 4.26, 95% CI 2.89 to 6.28); trouble speaking with memory and concentration (OR 4.24, 95% CI 3.28 to 5.48); and dysphagia with functional interference (OR 4.25, 95% CI 3.13 to 5.79).

Figure 1.

Respondents with parotid swelling, oral candidiasis, and tooth decay reported considerable impairment across QoL domains when compared with respondents without these oral manifestations (Table 4). These episodic events did not show a correlation between frequency of symptom and degree of impaired QoL. In contrast, dry mouth was only associated with poor QoL when symptoms were experienced daily, potentially reflecting the distribution of respondents showing predominantly daily symptoms.

Table 4.

Impact of oral manifestation by frequency on SS-related quality of life (n=2961)

| Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Mouth (n=2875) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Challenge & Burden* | 1.17 (0.52–2.65) | 1.27 (0.61–2.62) | 2.25 (1.15–4.44) |

| Function Interference | 1.65 (0.75–3.65) | 1.62 (0.81–3.25) | 2.36 (1.24–4.51) |

| Financial Burden | 2.22 (0.99–4.97) | 1.97 (0.96–4.04) | 4.10 (2.10–8.03) |

| Ability to Work | 1.17 (0.42–3.22) | 1.41 (0.56–3.53) | 1.76 (0.75–4.16) |

| Mood | 1.42 (0.59–3.44) | 1.64 (0.74–3.63) | 1.75 (0.83–3.68) |

| ADLs | 1.94 (0.72–5.23) | 2.40 (0.97–5.90) | 2.55 (1.08–6.01) |

| Memory & Concentration* | 2.13 (0.86–5.28) | 2.55 (1.12–5.83) | 2.82 (1.29–6.18) |

| Relationships | 2.14 (0.76–6.08) | 1.83 (0.70–4.81) | 2.06 (0.83–5.14) |

| Diet | 2.46 (0.84–7.21) | 2.71 (1.00–7.37) | 4.28 (1.64–11.2) |

| Parotid Swelling (n=1083) | |||

| Challenge & Burden* | 1.52 (1.12–2.06) | 1.93 (1.30–2.87) | 1.98 (1.35–2.91) |

| Function Interference | 1.98 (1.38–2.85) | 2.66 (1.60–4.42) | 2.53 (1.56–4.12) |

| Financial Burden | 2.09 (1.46–3.00) | 1.58 (1.02–2.43) | 2.45 (1.55–3.86) |

| Ability to Work | 1.60 (1.10–2.33) | 1.95 (1.15–3.28) | 1.84 (1.11–3.06) |

| Mood | 1.25 (0.92–1.70) | 1.34 (0.91–1.98) | 1.37 (0.93–2.02) |

| ADLs | 1.46 (1.07–1.99) | 1.52 (1.03–2.24) | 1.66 (1.13–2.43) |

| Memory & Concentration* | 1.51 (1.11–2.05) | 1.70 (1.15–2.51) | 1.77 (1.21–2.59) |

| Relationships | 1.83 (1.32–2.54) | 1.79 (1.18–2.70) | 2.15 (1.43–3.22) |

| Diet | 1.56 (1.16–2.11) | 2.41 (1.65–3.53) | 1.70 (1.17–2.47) |

| Oral Candidiasis (n=756) | |||

| Challenge & Burden* | 4.27 (2.68–6.80) | 3.25 (1.51–7.01) | 2.24 (1.30–3.86) |

| Function Interference | 1.80 (1.12–2.90) | 1.86 (0.80–4.31) | 2.26 (1.16–4.39) |

| Financial Burden | 2.97 (1.79–4.94) | 9.58 (2.28–40.3) | 2.07 (1.14–3.77) |

| Ability to Work | 1.83 (1.11–3.02) | 2.51 (0.99–6.34) | 4.25 (1.97–9.16) |

| Mood | 1.37 (0.93–2.04) | 1.91 (0.97–3.76) | 1.71 (1.01–2.90) |

| ADLs | 1.88 (1.27–2.78) | 2.66 (1.34–5.24) | 1.71 (1.02–2.87) |

| Memory & Concentration* | 1.41 (0.95–2.09) | 2.66 (1.31–5.40) | 2.54 (1.49–4.31) |

| Relationships | 1.70 (1.12–2.58) | 3.15 (1.58–6.29) | 2.54 (1.49–4.34) |

| Diet | 3.49 (2.36–5.15) | 4.18 (2.07–8.44) | 2.09 (1.25–3.51) |

| Sialolithiasis/Infection (n=434) | |||

| Challenge & Burden* | 2.05 (1.11–3.77) | 6.85 (1.54–30.6) | 10.8 (2.52–46.6) |

| Function Interference | 2.62 (1.16–5.92) | 2.82 (0.63–12.6) | 10.2 (1.36–76.1) |

| Financial Burden | 3.10 (1.37–7.02) | 3.92 (0.87–17.6) | 2.53 (0.85–7.57) |

| Ability to Work | 2.12 (1.04–4.35) | 2.73 (0.64–11.7) | 6.18 (1.66–23.0) |

| Mood | 1.89 (1.07–3.32) | 4.92 (1.65–14.7) | 1.89 (0.81–4.40) |

| ADLs | 2.45 (1.38–4.35) | 6.39 (2.01–20.3) | 2.39 (1.03–5.52) |

| Memory & Concentration* | 1.90 (1.06–3.43) | 9.83 (2.16–44.7) | 1.68 (0.72–3.92) |

| Relationships | 1.54 (0.83–2.85) | 12.3 (3.84–39.4) | 3.58 (1.53–8.36) |

| Diet | 1.61 (0.92–2.80) | 5.62 (1.79–17.7) | 3.70 (1.55–8.82) |

| Tooth Decay (n=1747) | |||

| Challenge & Burden* | 1.31 (0.95–1.80) | 3.35 (1.96–5.74) | 2.48 (1.87–3.29) |

| Function Interference | 1.09 (0.78–1.52) | 3.05 (1.58–5.90) | 2.02 (1.47–2.76) |

| Financial Burden | 2.28 (1.60–3.25) | 3.62 (1.97–6.64) | 3.35 (2.43–4.62) |

| Ability to Work | 1.59 (1.05–2.39) | 1.55 (0.82–2.91) | 1.52 (1.06–2.18) |

| Mood | 1.36 (0.96–1.91) | 2.56 (1.57–4.20) | 1.89 (1.42–2.50) |

| ADLs | 1.93 (1.38–2.70) | 2.74 (1.67–4.48) | 2.41 (1.83–3.18) |

| Memory & Concentration* | 1.92 (1.39–2.67) | 2.14 (1.30–3.53) | 2.57 (1.94–3.39) |

| Relationships | 1.97 (1.37–2.84) | 3.33 (1.98–5.58) | 2.42 (1.79–3.28) |

| Diet | 2.04 (1.47–2.83) | 2.55 (1.57–4.13) | 2.61 (1.98–3.44) |

All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, and employment status.

Composite score. Bolded confidence interval (CI) =p<0.05. Referent value = never.

Systemic Manifestations

Figure 1 also shows the impact of SS systemic manifestations on QoL. ILD was associated with a moderate increase in impairment in eight of nine QoL domains. The greatest impact of ILD was on ADLs (OR 2.63, 95% CI 2.01 to 3.44). Neuropathy was associated with impaired QoL in all domains, with the greatest impact on functional interference (OR 1.94, 95%CI 1.60 to 2.35). Petechiae/purpura/cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis, and interstitial nephritis also impacted several QoL domains, but to a lesser extent than ILD or neuropathy (Table 5). Systemic manifestations of leukopenia, PBC, RTA, autoimmune hepatitis, and lymphoma did not significantly impact QoL, and were less frequent overall (data not shown).

Table 5.

Impact of systemic SS manifestations on quality of life (n=2961)

| Lung Disease (n=305) | Adjusted OR (95% Cl) |

|---|---|

| Challenge & Burden | 1.81 (1.37–2.37) |

| Function Interference | 1.97 (1.41–2.75) |

| Financial Burden | 1.96 (1.44–2.67) |

| Ability to Work | 1.64(1.13–2.39) |

| Mood | 1.05 (0.80–1.39) |

| ADLs | 2.63 (2.01–3.44) |

| Memory & Concentration | 2.10 (1.60–2.75) |

| Relationship | 1.93 (1.45–2.56) |

| Diet | 1.37 (1.05–1.78) |

| Purpura/Petechiae/Cryoglobulinemia (n=162) | |

| Challenge & Burden | 1.82 (1.27–2.63) |

| Function Interference | 1.50 (0.99–2.27) |

| Financial Burden | 1.83 (1.21–2.76) |

| Ability to Work | 1.74(1.08–2.81) |

| Mood | 1.02 (0.71–1.47) |

| ADLs | 1.81 (1.28–2.57) |

| Memory & Concentration | 1.02 (0.72–1.46) |

| Relationship | 1.31 (0.89–1.91) |

| Diet | 2.02 (1.44–2.86) |

| Vasculitis (n=238) | |

| Challenge & Burden | 1.38 (1.02–1.86) |

| Function Interference | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) |

| Financial Burden | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) |

| Ability to Work | 0.94 (0.63–1.40) |

| Mood | 0.74 (0.54–1.01) |

| ADLs | 1.01 (0.74–1.37) |

| Memory & Concentration | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) |

| Relationship | 1.16 (0.83–1.61) |

| Diet | 1.10 (0.82–1.48) |

| Neuropathy (n=1120) | |

| Challenge & Burden | 1.74 (1.47–2.05) |

| Function Interference | 1.94 (1.60–2.35) |

| Financial Burden | 1.59 (1.33–1.91) |

| Ability to Work | 1.58 (1.27–1.97) |

| Mood | 1.43 (1.20–1.70) |

| ADLs | 1.74 (1.46–2.07) |

| Memory & Concentration | 1.85 (1.56–2.20) |

| Relationship | 1.65 (1.36–2.00) |

| Diet | 1.46 (1.23–1.73) |

| Interstitial Nephritis (n=30) | |

| Challenge & Burden | 3.06 (1.21–7.76) |

| Function Interference | 9.60 (1.29–71.47) |

| Financial Burden | 2.03 (0.75–5.50) |

| Ability to Work | 5.25 (1.08–25.4) |

| Mood | 2.64 (1.18–5.88) |

| ADLs | 2.50 (1.10–5.66) |

| Memory & Concentration | 2.49 (1.06–5.83) |

| Relationship | 1.85 (0.79–4.32) |

| Diet | 1.67 (0.76–3.67) |

All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, and employment status. Bolded confidence interval (CI) =p<0.05. Referent value = never.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to respondents who reported treatment with hydroxychloroquine, DMARDs, or biologic therapy. Of 2,961 respondents, 2,228 (75%) reported receiving therapy with hydroxychloroquine, DMARDs, or biologic agents. We performed a repeat analysis on 20% of the oral symptom predictors and QoL outcomes. The findings in this restricted cohort were consistent with the findings of the full sample of 2,961 respondents (data not shown). We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, systemic lupus erythematous, and systemic sclerosis. After exclusion, 1,888 respondents (64%) were included in a sensitivity analysis on 20% of the oral symptom and systemic manifestations and QoL outcomes. We found similar results in this more defined cohort. For example, mouth ulcers/sores showed a dose response with severity of functional interference [monthly (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.7–3.1), weekly (, OR 2.4 95% CI 1.6–3.5), daily (, OR 3.4 1.9–6.3)]. A similar dose-response relationship was seen for dysphagia [monthly (OR 1.8, (95% CI 1.3–2.5), weekly (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.9–3.7), and daily (OR 3.8, (95% CI 2.6–5.5)].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the largest to date evaluating the associations between SS-specific oral manifestations and QoL. The results of this survey, designed by patients with SS as well as experts, demonstrate that oral manifestations have a considerable negative association with QoL and the financial well-being of patients with this disease. The most consistent and notable associations with QoL were for the oral symptoms such as mouth ulcers or sores, dysphagia, and trouble speaking. Even at lower frequencies, episodic symptoms, such as tooth decay, were strongly associated with QoL, indicating that self-limited oral symptoms cause a sustained impact on QoL.

Our findings of strong associations between dysphagia and trouble speaking and worse QoL are consistent with other studies.(16–18) In particular, a previous study of 101 patients with primary or secondary SS found dysphagia to be significantly associated with reduced HRQoL, as measured by the Short Form (SF)-36 instrument.(18) In the same cohort of 101 SS patients, voice disorders such as throat clearing, throat soreness, discomfort with use, and difficulty with vocal projection were associated with reduced QoL.(19) Voice discomfort was most strongly associated with the mental QoL component of the SF-36. Interestingly, despite most patients reporting voice disorders, only 16% sought professional help for their vocal symptoms in that study.(19) In the current study, we similarly found that trouble speaking is commonly associated with worse QoL.

Previous examinations of OHRQoL in SS used global metrics such as OHIP and XeQoLS.(5–7, 9, 14) These studies demonstrated that patients with SS have worse overall OHRQoL than controls,(7) and most have shown worse OHRQoL to be correlated with global HRQoL.(5, 6) Stewart et al. studied 39 patients with SS and identified significant associations between OHIP-14 and SF-36 impairment.(5) In a similar larger study (n=246), Enger et al. found a significant correlation between OHIP-14 and SF-36.(6) In contrast, Cho et al. studied 104 patients with SS and found no correlation between xerostomia and SF-36.(20)

Despite high variability of oral symptoms experienced in SS, few studies have evaluated the association between SS-specific oral symptoms and QoL to inform interventions to improve QoL.(21) Previous qualitative studies identified SS-specific symptoms and SS-specific social, career, financial, and emotional and psychological challenges, but did not study the relationship between individual SS-specific symptoms and QoL (22, 23) Aside from classic dry mouth, reduction in OHRQoL has been associated with dysgeusia, burning tongue sensation, halitosis, andoral candidiasis.(9, 10, 24) In a study of 31 patients with SS, OHIP-14 scores were associated with dysgeusia, burning tongue sensation, and halitosis.(9) Another study of 60 patients with SS also found oral candidiasis to be correlated with OHIP-14.(10) Each of these studies had fewer than 100 patients. Our findings add to these previous smaller studies by quantifying the relative burden of multiple discrete SS oral symptoms on HRQoL to prioritize treatment interventions.

Interestingly, systemic manifestations of SS, such as ILD and neuropathy, appear to impact reported QoL to a lesser extent than oral manifestations. Both neuropathy and ILD have been reported to influence HRQoL, but without relative comparison with other systemic manifestations.(25, 26) We found that many systemic manifestations of SS had little to no impact on QoL. This may reflect that such patients already receive adequate attention and medical care. Although the data are conflicting, the lack of an association between systemic SS and HRQoL has previously been reported in the literature, supporting the conclusion that symptoms such as dryness and fatigue may influence QoL more than systemic manifestations.(20, 27) In a separate paper using the same participant sample as the current study, we recently demonstrated that SS-related ocular dryness was also associated with QoL to a greater extent than systemic manifestations.(28) However, other studies have found that systemic disease may correlate with HRQoL, which suggests the need for future research on this subject.(29)

Given the focus of most clinicians on the diagnosis and management of systemic manifestations of SS, the findings presented here suggest that treatment of oral manifestations should receive greater attention. For example, patients with SS experiencing dysphagia could be referred to a swallowing therapist. Patients with trouble speaking could be referred to a speech therapist or treated with nebulized saline.(30) Interestingly, dysphagia, trouble speaking, and mouth ulcers can all be attributed to reduced salivary flow and are often treated with topical moisturizers or secretagogues. We found a low percentage of patients treated with secretagogues, a primary symptomatic treatment for dysphagia (36% current use), suggesting underprescribing, lack of efficacy, and/or significant adverse effects of this therapy. This low number may reflect known side effects of secretagogues (e.g., diaphoresis in up to 25% of patients and lack of efficacy in up to 47% of patients).(31) Also, the low number of current users in the current study likely emphasizes the paucity of effective treatment for oral symptoms in SS.

The current study has a number of strengths, such as the large sample size, broad survey content developed with SS experts and patients with SS, and respondent demographics that are typical of patients with SS. For example, older age, female sex, majority non-Hispanic white population, and history of prescribed SS-related medications, such as hydroxychloroquine and secretagogues, increase the representativeness of the current study population.

We acknowledge a number of limitations. First, the ascertainment of SS diagnosis was through self-report (i.e., without independent verification through established criteria, such as the 2016 ACR/EULAR criteria).(32) However, sensitivity analysis in patients who reported receiving prescription therapy, indicating likely diagnosis, rendered similar results. Second, systemic manifestations were self-reported and not externally validated. Further, the survey did not collect data needed for calculating EULAR Sjӧgren’s syndrome disease activity indices (ESSDAI), limiting comparisons to available data and future research in the field is needed. Third, we are unable to rule out response and recall biases. For example, bias might be present if a large proportion of younger individuals did not respond to the survey in part due to a preference for electronic modes of survey administration. However, as discussed previously, the respondent demographics reflect the known epidemiology of SS suggesting that this is unlikely. Similarly, patients with more severe disease or overlap might have been more likely to respond to this survey, and this might explain the relatively high number of respondents reporting a history of biologic therapy. Fourth, we are unable to generalize our results to populations of patients with SS that are not older, female, and majority non-Hispanic white. Fifth, low response rates for some outcomes precluded full analysis. Sixth, the current study reports data on a cross-section of patients in 2016. Future studies should prospectively follow-up with patients with incident SS to more robustly estimate the impact of oral symptoms on trajectories of QoL. Lastly, although patients with SS and expert providers developed this survey, it did not utilize validated questionnaires. Nevertheless, the findings of this initial Sjӧgren’s Foundation survey provide important information for the development and validation of an SS-specific OHRQoL questionnaire.

In summary, the results presented in this study suggest that targeted treatment of specific oral symptoms and signs might offer the greatest improvements in SS-related QoL. In particular, during SS visits, we recommend screening for dysphagia and trouble speaking and developing targeted treatment plans, such as for speech and swallow therapy. Further, we recommend evaluation and appropriate targeted treatment of mouth ulcers to reduce their severity and recurrence. By detecting and treating key oral symptoms or signs, clinicians have the opportunity to improve the QoL of patients with SS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 1KL2TR002374. Dr. Baer is supported by NIH/NIDCR contract 75N92019P00427. Dr. Bunya is supported by NIH/NEI R01 EY026972. Mr. Makara’s time was paid for by the Sjögren’s Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors of this paper have no current financial support or other benefits from commercial sources for the reported work, or any other financial interests that could create a potential conflict of interest or appearance of a conflict of interest with regard to the work.

SS McCoy MD MS, CM Bartels MD MS, IJ Saldanha MBBS MPH PhD, VY Bunya MD MSCE, EK Akpek MD, MA Makara MPH, AN Baer MD

References

- 1.Kocer B, Tezcan ME, Batur HZ, Haznedaroglu S, Goker B, Irkec C, et al. Cognition, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: correlations. Brain Behav 2016;6:e00586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lackner A, Ficjan A, Stradner MH, Hermann J, Unger J, Stamm T, et al. It’s more than dryness and fatigue: The patient perspective on health-related quality of life in Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome - A qualitative study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Huddleston Slater JJ, Spijkervet FK, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A, et al. Health-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1077–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lendrem D, Mitchell S, McMeekin P, Bowman S, Price E, Pease CT, et al. Health-related utility values of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome and its predictors. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1362–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart CM, Berg KM, Cha S, Reeves WH. Salivary dysfunction and quality of life in Sjogren syndrome: a critical oral-systemic connection. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:291–9; quiz 358–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Enger TB, Palm O, Garen T, Sandvik L, Jensen JL. Oral distress in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: implications for health-related quality of life. Eur J Oral Sci 2011;119:474–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F. Quality of life in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and sicca complex. J Oral Rehabil 2008;35:875–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Martinez G, Zamora-Legoff V, Hernandez Molina G. Oral health-related quality of life in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Reumatol Clin 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusthen S, Young A, Herlofson BB, Aqrawi LA, Rykke M, Hove LH, et al. Oral disorders, saliva secretion, and oral health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Eur J Oral Sci 2017;125:265–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tashbayev B, Garen T, Palm Ø, Chen X, Herlofson BB, Young A, et al. Patients with non-Sjögren’s sicca report poorer general and oral health-related quality of life than patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 2020;10:2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billings M, Dye BA, Iafolla T, Baer AN, Grisius M, Alevizos I. Significance and Implications of Patient-reported Xerostomia in Sjogren’s Syndrome: Findings From the National Institutes of Health Cohort. EBioMedicine 2016;12:270–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health 1994;11:3–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henson BS, Inglehart MR, Eisbruch A, Ship JA. Preserved salivary output and xerostomia-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients receiving parotid-sparing radiotherapy. Oral Oncol 2001;37:84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMillan AS, Leung KC, Leung WK, Wong MC, Lau CS, Mok TM. Impact of Sjogren’s syndrome on oral health-related quality of life in southern Chinese. J Oral Rehabil 2004;31:653–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Najera C, Taylor S, Crawford S, Narasimhan P, Shao X, Li J. Characteristics and Treatments of Patients With Sjӧgren’s Syndrome in a Real-World Setting. Paper presented at: EULAR Annual European Congress of Rheumatology; 2019 June 12–15; Madrid, Spain [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierce JL, Tanner K, Merrill RM, Miller KL, Kendall KA, Roy N. Swallowing Disorders in Sjogren’s Syndrome: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Effects on Quality of Life. Dysphagia 2016;31:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eyigör S, Sezgin B, Karabulut G, Öztürk K, Göde S, Kirazlı T. Evaluation of Swallowing Functions in Patients with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Dysphagia 2017;32:271–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce JL, Tanner K, Merrill RM, Miller KL, Kendall KA, Roy N. Swallowing Disorders in Sjögren’s Syndrome: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Effects on Quality of Life. Dysphagia 2016;31:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner K, Pierce JL, Merrill RM, Miller KL, Kendall KA, Roy N. The Quality of Life Burden Associated With Voice Disorders in Sjogren’s Syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015;124:721–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho HJ, Yoo JJ, Yun CY, Kang EH, Lee HJ, Hyon JY, et al. The EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome patient reported index as an independent determinant of health-related quality of life in primary Sjogren’s syndrome patients: in comparison with non-Sjogren’s sicca patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:2208–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox PC, Bowman SJ, Segal B, Vivino FB, Murukutla N, Choueiri K, et al. Oral involvement in primary Sjögren syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:1592–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lackner A, Ficjan A, Stradner MH, Hermann J, Unger J, Stamm T, et al. It’s more than dryness and fatigue: The patient perspective on health-related quality of life in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome - A qualitative study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0172056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gairy K, Ruark K, Sinclair SM, Brandwood H, Nelsen L. An Innovative Online Qualitative Study to Explore the Symptom Experience of Patients with Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome. Rheumatol Ther 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamel UF, Maddison P, Whitaker R. Impact of primary Sjogren’s syndrome on smell and taste: effect on quality of life. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1512–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao R, Wang Y, Zhou W, Guo J, He M, Li P, et al. Associated factors with interstitial lung disease and health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:483–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaskólska M, Chylińska M, Masiak A, Nowicka-Sauer K, Siemiński M, Ziętkiewicz M, et al. Peripheral neuropathy and health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a preliminary report. Rheumatol Int 2020;40:1267–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milin M, Cornec D, Chastaing M, Griner V, Berrouiguet S, Nowak E, et al. Sicca symptoms are associated with similar fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality-of-life impairments in patients with and without primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Joint Bone Spine 2016;83:681–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saldanha IJ, Bunya VY, McCoy SS, Makara M, Baer AN, Akpek EK. Ocular Manifestations and Burden Related To Sjögren’s Syndrome: Results of a Patient Survey. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;S0002–9394:30285–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omma A, Tecer D, Kucuksahin O, Sandikci SC, Yildiz F, Erten S. Do the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Sjögren’s syndrome outcome measures correlate with impaired quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression in primary Sjögren’s syndrome? Arch Med Sci 2018;14:830–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanner K, Roy N, Merrill RM, Kendall K, Miller KL, Clegg DO, et al. Comparing nebulized water versus saline after laryngeal desiccation challenge in Sjogren’s Syndrome. Laryngoscope 2013;123:2787–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noaiseh G, Baker JF, Vivino FB. Comparison of the discontinuation rates and side-effect profiles of pilocarpine and cevimeline for xerostomia in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:575–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, Criswell LA, Labetoulle M, Lietman TM, et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:35–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.