Abstract

Background

The pathophysiological understanding of the inflammatory response in necrotizing soft‐tissue infection (NSTI) and its impact on clinical progression and outcomes are not resolved. Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO2) treatment serves as an adjunctive treatment; however, its immunomodulatory effects in the treatment of NSTI remains unknown. Accordingly, we evaluated fluctuations in inflammatory markers during courses of HBO2 treatment and assessed the overall inflammatory response during the first 3 days after admission.

Methods

In 242 patients with NSTI, we measured plasma TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐10, and granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (G‐CSF) upon admission and daily for three days, and before/after HBO2 in the 209 patients recieving HBO2. We assessed the severity of disease by Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, SOFA score, and blood lactate.

Results

In paired analyses, HBO2 treatment was associated with a decrease in IL‐6 in patients with Group A‐Streptococcus NSTI (first HBO2 treatment, median difference −29.5 pg/ml; second HBO2 treatment, median difference −7.6 pg/ml), and overall a decrease in G‐CSF (first HBO2 treatment, median difference −22.5 pg/ml; 2− HBO2 treatment, median difference −20.4 pg/ml). Patients presenting with shock had significantly higher baseline cytokines values compared to non‐shock patients (TNF‐α: 51.9 vs. 23.6, IL‐1β: 1.39 vs 0.61, IL‐6: 542.9 vs. 57.5, IL‐10: 21.7 vs. 3.3 and G‐CSF: 246.3 vs. 11.8 pg/ml; all p < 0.001). Longitudinal analyses demonstrated higher concentrations in septic shock patients and those receiving renal‐replacement therapy. All cytokines were significantly correlated to SAPS II, SOFA score, and blood lactate. In adjusted analysis, high baseline G‐CSF was associated with 30‐day mortality (OR 2.83, 95% CI: 1.01–8.00, p = 0.047).

Conclusion

In patients with NSTI, HBO2 treatment may induce immunomodulatory effects by decreasing plasma G‐CSF and IL‐6. High levels of inflammatory markers were associated with disease severity, whereas high baseline G‐CSF was associated with increased 30‐day mortality.

Keywords: cytokine, group A‐Streptococcus, anaerobic infection, hyperbaric oxygen treatment, necrotizing soft‐tissue infection, outcome, survival

In necrotizing soft‐tissue infections, the inflammatory response at admission is immense with a rapid decline during the first 3 days. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment may induce immunomodulatory effects by decreasing IL‐6 and G‐CSF potentially limiting the risk of collateral damage.

1. INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing soft‐tissue infection (NSTI) is a serious and life‐threatening disease. NSTI is characterized by rapidly progressing soft‐tissue inflammation and necrosis (Stevens & Bryant, 2017). NSTI is rare, with an estimated annual incidence of 4.5 cases per 100,000 in the United States (Soltani et al., 2014) and 1.99 in Denmark (Hedetoft et al., 2020). Prompt and repeated surgical debridement; antibiotic therapy and supportive intensive care are the mainstays in NSTI treatment. Despite rigorous treatment, patients with NSTI have high mortality rates, risk of amputation and often protracted rehabilitation stays (Hakkarainen et al., 2014).

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO2) treatment might serve as an adjunctive to the multidisciplinary course of treatment (Anderson & Jacoby, 2019; Mathieu et al., 2017). Retrospective observational studies have shown improved survival in patients with NSTI when HBO2 treatment is given as an adjunct to regular treatment (Devaney et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2014), and register‐based studies have demonstrated lower mortality in patients who received HBO2 treatment (Hedetoft et al., 2020; Soh et al., 2012). Although patients with NSTI might benefit from HBO2 treatment, no prospective controlled studies exist (Levett et al., 2015). This could be due to the rarity of the disease, ethical concerns, limited access to HBO2 treatment, and a lack of pharmaceutical interest in the funding of such studies using a non‐patented drug.

The antimicrobial mechanisms of action of HBO2 treatment is diverse and includes many specific actions. HBO2 treatment induces several different physiological and biochemical responses. Three main antimicrobial mechanisms have been described including direct antimicrobial effects in the result of HBO2‐derived formation of reactive oxygen species, synergistic effects with antibiotics, and immune‐modulatory effects (Memar et al., 2019; Thom, 2009). First, the formation of reactive oxygen species generates oxidative stress which is fundamental to HBO2 treatment (Thom, 2009). Oxidative stress by the formation of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species is in general believed to be destructive to bacterial DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids (Memar et al., 2018). Second, HBO2 treatment induces aerobic metabolism of the bacteria while reoxygenating the O2‐depleted tissue (Jensen et al., 2019; Lerche et al., 2017). This factor has shown to be critical since some antibiotics (β‐lactams, aminoglycosides, and quinolones) are dependent on aerobic metabolism for an optimal effect (Memar et al., 2019). In that respect, HBO2 treatment has been shown to enhance the efficacy of tobramycin in Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis (Lerche et al., 2017) and ciprofloxacin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infected tissue (Kolpen et al., 2016). Both tissue hypoxia and biofilm formation are pathologies present in NSTI patients (Korhonen et al., 2000; Siemens et al., 2016; Wang & Hung, 2004) and a target for correction by employing HBO2 treatment (Camporesi & Bosco, 2014; Jensen et al., 2019). Third, HBO2 treatment has shown to induce substantial effects on the expression of immune‐modulatory cytokines by decreasing proinflammatory cytokines such as IL‐1, IL‐6, and TNF‐α (Weisz et al., 1997) and elevating the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10 (Pan et al., 2013).

NSTI may arise either through a defined portal of entry or be cryptogenic without any breach of the skin, and either evolutions give rise to an excessive inflammatory response and promote platelet–leukocyte aggregation consequently causing endothelial damage, vascular occlusion, and widespread necrosis in the deep tissue (Stevens & Bryant, 2017). Particularly, the toxin‐induced inflammatory response may have a central role in both tissue pathology and systemic toxicity (Johansson et al., 2010; Morgan, 2010). Plasma levels of proinflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokines are elevated in sepsis non‐survivors (Pierrakos & Vincent, 2010). However, only a few prospective studies have investigated cytokine levels in NSTI patients (Hansen et al., 2017; Lungstras‐Bufler et al., 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2006) demonstrating IL‐1β and IL‐10 to be associated with 30‐day mortality and IL‐6 to be associated with disease severity in NSTI (Hansen et al., 2017). In this respect, it is important to note that HBO2 treatment has been proposed to have regulatory effects on the expression of IL‐1β during infections (Lerche et al., 2017). Likewise, in experimental sepsis in rats HBO2 treatment has shown to stimulate immune‐modulatory activities including IL‐10 modulation resulting in improved survival (Bærnthsen et al., 2017; Buras et al., 2006), but timing and dosage are essential factors for the overall outcome (Bærnthsen et al., 2017; Buras et al., 2006; Lerche et al., 2017).

The lack of clinical studies, the inconsistency in the use of HBO2 treatment and the uncertainties surrounding the mechanisms of action all highlight the need for studies describing the potential effects of HBO2 treatment in NSTI treatment. Of particular relevance is the question if HBO2 treatment can induce immune‐modulatory effects in patients with NSTI as experimental studies have suggested (Bærnthsen et al., 2017; Buras et al., 2006; Lerche et al., 2017). Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with NSTI during the first 3 days after admission. We focused primarily on variations in IL‐6 before and after HBO2 treatment. We hypothesized that HBO2 treatment reduces plasma levels of IL‐6 and that high levels of IL‐6 at admission are associated with disease severity and 30‐day mortality. Secondarily, we focused on the possible HBO2‐mediated fluctuations in TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐10, and granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor (G‐CSF) and their association with disease severity and mortality.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

The present study was a sub‐study of the Danish cohort from the international, prospective, observational cohort‐study (INFECT, ClinicalTrials.gov number; NCT01790698) including patients with NSTI admitted to Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark between February 2013 and March 2017 in which some data have been reported elsewhere (Madsen et al., 2019). We included patients aged 18 years or older after diagnosis of NSTI was confirmed by a surgeon at either the primary operation or at revision. We excluded patients in whom the surgery revealed no NSTI.

2.2. Patient management

Patients were treated according to a standardized multidisciplinary course including frequent surgical debridement (three revisions during first 24 h. Thereafter repeated as necessary), initial broad‐spectrum antibiotics (meropenem, ciprofloxacin, and clindamycin), supportive intensive care, immunoglobulin therapy if indicated (considered in patients with septic shock and Group A‐Streptococcus infection, 25 g/day for 3 days), and HBO2 treatment (at least three sessions of 90 min at 284 kPa, preferably two sessions within 24 h from admission and minimum three sessions within 72 h; Madsen et al., 2019).

2.3. Data collection

Patients had blood sampled from either an arterial or central venous line into an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid sample tube upon admission (baseline) and at each of the following 3 days (all between 08:00 and 12:00 hours). Moreover, blood was sampled immediately before and after each session of HBO2 treatment. Samples were put on ice and centrifugated within 40 min. Plasma was collected and stored at −80°C until analysis. Predefined clinical data, including patients’ characteristics, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS)‐II, microbiological findings, and supportive modalities were registered into an electronic clinical database by dedicated personnel (Madsen et al., 2018).

2.4. Multiplex bead array assays

All samples were studied by magnetic bead suspension array using a premixed 5‐plex panel (Bio‐Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions except that the samples were diluted in 1:3. The premixed 5‐plex panel contained tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), interleukin 1β (IL‐1β), interleukin 6 (IL‐6), interleukin 10 (IL‐10), and G‐CSF. Nine‐point standard curves were generated for each cytokine. All samples were analyzed using Bio‐Plex 100 System, and the concentrations were calculated using the Bio‐Plex Manager 6.0 (Bio‐Rad Laboratories). Extrapolated concentrations were used if the values fell outside the 9‐point standard curve. However, if values could not be extrapolated, values below limit were set to lowest extrapolated value on the specific panel. No values were above the detection limit. All samples from each patient were analyzed on the same panel.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome was difference in IL‐6 before and after HBO2 treatment. Secondary analyses included differences in TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐10, and G‐CSF before and after HBO2 treatment assessed in the entire cohort and in subgroups of patients with the presence of Group A‐Streptococcus or anaerobic species. Furthermore, the association of baseline cytokine concentration with SAPS II, SOFA score at admission, serum lactate, use of renal replacement therapy (RRT) (any use within first 7 days of ICU admission), amputation (in patients with infection of an extremity), and 30‐day all‐cause mortality were evaluated.

2.6. Statistics

Continuous data are presented as medians (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical data as absolute numbers (%). Testing for normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilks test. As data were not normally distributed, continuous data were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test for non‐paired data and Wilcoxon signed‐rank test for paired data (before/after HBO2 treatment) with adjusted P values using Benjamini–Hochberg do to multiple comparisons. Longitudinal cytokine concentrations (admission, days 1, 2, and 3) were presented as the area under the curve (AUC) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. We assessed correlations by Spearman's rank correlation test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were analyzed and ROC‐AUC, sensitivity, specificity, positive‐predictive value, and negative‐predictive value were reported for baseline cytokines level on 30‐day mortality. Logistic regression analyses with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were performed to evaluate the association between baseline cytokine levels and 30‐day mortality and adjusted for differences in age, sex, comorbidities, and SOFA score at admission. We used the Youden Index optimal cutoff point to categorize low and high cytokine levels in logistic analyses. Patients who were lost to follow‐up were excluded from entering survival analyses. p‐values were reported as exact unless <0.001. p‐values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R v.3.3.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing Platform) with additional RStudio v.1.0.136 (Rstudio, Inc.) software attached. Figures were created using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Inc.).

2.7. Ethics

The study abided the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of Capital Region (H‐19016085) and The Danish Data Protection Agency (VD‐2019‐179). Written informed content was obtained from all patients or their legal surrogates. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed in the drafting of this manuscript (Elm et al., 2007).

3. RESULTS

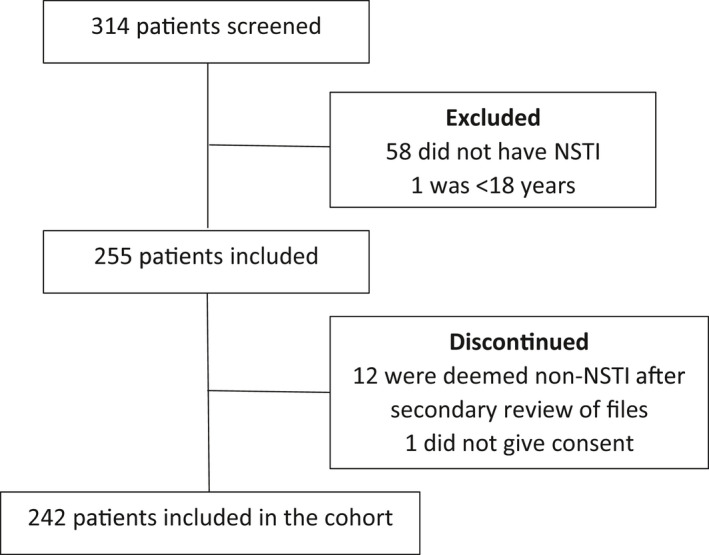

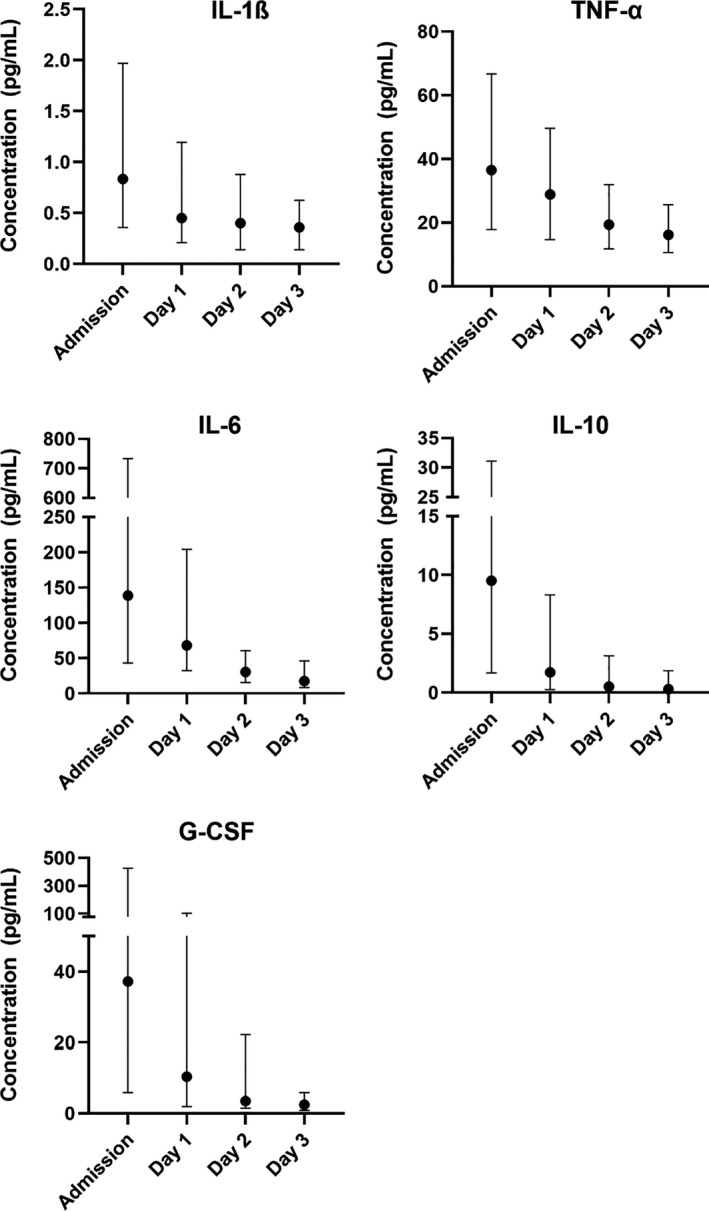

We included 242 patients with confirmed NSTI between February 2013 and March 2017 (Figure 1). Patients’ characteristics, including baseline cytokine levels, laboratory values, microbial findings, clinical severity scores, and outcomes, are presented in Table 1. In total, 209 (86%) patients received at least one session of HBO2 treatment with a median number of three sessions (3–3). Three patients were lost to follow‐up at day 30 (98.8% follow‐up). All cytokines demonstrated highest levels at admission with a moderate decrease toward days 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of patients included in the study. Patients with suspected NSTI were screened for eligibility. Patients were excluded if they did not meet the criteria of inclusion. After inclusion, patients’ files were reviewed and 12 were deemed non‐NSTI due to no intraoperative signs of necrotizing soft tissue infection. One patient was discontinued as informed consent was not obtainable

TABLE 1.

Patients characteristics

| NSTI (n = 242) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 62 (51–61) |

| Sex, male | 144 (60) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 (24–31) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 110 (45) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 17 (7) |

| COPD | 30 (12) |

| Diabetes (type I and II) | 68 (28) |

| Immune deficiency | 12 (5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 14 (6) |

| Malignancy | 19 (8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 31 (13) |

| Rheumatoid disease | 16 (7) |

| No comorbidities | 68 (28) |

| Microbiological findings | |

| Monomicrobial infections (n = 96, 40%) | |

| Group A‐Streptococcus | 50 (52) |

| Group B‐Streptococcus | 1 (1) |

| Group C/G‐Streptococcus | 9 (9) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (11) |

| Aerobic gram‐negative species | 15 (16) |

| Clostridium species | 5 (5) |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 3 (3) |

| Other streptococci | 2 (2) |

| Polymicrobial infections (n = 126, 52%) | |

| With presence of Group A‐Streptococcus | 8 (6) |

| With presence of Group B‐Streptococcus | 10 (8) |

| With presence of Group C/G‐Streptococcus | 8 (6) |

| With presence of S. aureus | 9 (7) |

| With presence of Clostridium sp. | 2 (2) |

| Other polymicrobial infections | 89 (71) |

| Negative findings | 20 (8) |

| Cytokines (pg/ml) | |

| IL‐6 | 138.6 (43.3–733.1) |

| IL‐1β | 0.8 (0.4–2.0) |

| TNF‐α | 36.5 (17.8–66.7) |

| IL‐10 | 9.5 (1.7–31.1) |

| G‐CSF | 37.2 (5.9–426.0) |

| Biochemistry | |

| Leukocyte count (109/L) | 16.6 (11.1–23.4) |

| C‐reactive protein (mg/L) | 226 (154–309) |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 109 (74–192) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.2 (1.3–3.9) |

| Other | |

| SOFA score a | 8 (6–10) |

| SAPS II b | 44 (35–55) |

| Septic shock upon admission c | 114 (47) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 230 (95) |

| Amputation within 7 days d | 33 (14) |

| RRT within 7 days | 42 (17) |

| HBOT, at any time | 209 (86) |

| HBOT, number of sessions | 3 (3–3) |

| 30‐day mortality, % (95% CI) | 17 (13–23) |

| 90‐day mortality, % (95% CI) e | 23 (17–28) |

Continuous data are presented as medians (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical data as absolute numbers (%). Blood samples were obtained at arrival to specialized hospital.

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HBOT, Hyperbaric oxygen therapy; RRT. Renal‐replacement therapy.

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (Day 1); data were missing for 9 (4%) patients.

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II); data were missing for 9 (4%) patients.

Septic shock is defined as lactate >2 mmol/L and use of vasopressor or inotrope; data were missing for 1 patient (>0.01%).

One hundred twelve patients with infection located to the extremities.

Three patients were lost to follow‐up at day 90.

FIGURE 2.

Cytokine concentrations at admission (n = 242), day 1, day 2 and day 3. Data are plotted as medians with interquartile range. Note the two‐segmented y‐axis for IL‐6, IL‐10 and G‐CSF

3.1. HBO2 treatment and cytokine response

In paired‐analyses, a statistically significant increase in IL‐6 was observed after the first HBO2 treatment compared to samples taken before the first HBO2 treatment (median 7.5 pg/ml, 95% CI 2.4–15.1, p = 0.008), and after the second HBO2 treatment a decrease in IL‐6 was observed compared to samples taken before the second HBO2 treatment (median −3.2 pg/ml, 95% CI −5.9 to −1.1, p = 0.01). No differences were found in IL‐6 before/after the third HBO2 treatment. G‐CSF showed a consistent decrease before and after all HBO2 treatments (Table 2). No difference in plasma levels was observed for the remaining cytokines (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Plasma cytokine concentrations before and after first, second, and third HBOT

| First HBO2 | Second HBO2 | Third HBO2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pg/ml | Before | After | MD | p (Adj.) | Before | After | MD | p (Adj.) | Before | After | MD | p (Adj.) | |

| All patients (n = 209) | IL‐1β | 0.66 (0.23–1.23) | 0.68 (0.24–1.45) | −0.05 (−0.19 to 0.07) | .55 | 0.37 (0.14–0.91) | 0.39 (0.14–0.93) | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.14) | .78 | 0.39 (0.17–0.85) | 0.41 (0.19–1.01) | 0.05 (−0.08 to 0.19) | .53 |

| TNF‐α | 31.8 (18.2–55.8) | 30.4 (18.4–50.2) | −1.0 (−2.6 to 0.5) | .46 | 22.3 (14.8–40.5) | 23.1 (13.9–40.5) | −0.2 (−1.4 to 1.0) | .77 | 19.2 (10.8–30.9) | 17.5 (12.6–30.0) | 0.5 (−0.5 to 1.7) | .47 | |

| IL‐6 | 84.4 (37.1–237.6) | 87.1 (39.2–216.7) | 7.5 (2.4–15.1) | .008 | 47.1 (25.2–113.3) | 45.0 (22.0–119.1) | −3.2 (−5.9 to −1.1) | .01 | 27.8 (13.4–53.2) | 25.4 (13.1–53.3) | −0.8 (−2.0 to 0.5) | .46 | |

| IL‐10 | 3.7 (0.3–11.7) | 3.0 (0.5–11.4) | −0.8 (−1.7 to −0.2) | .12 | 0.8 (0.3–4.3) | 1.2 (0.3–4.5) | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.8) | .68 | 0.3 (0.2–2.7) | 0.3 (0.2–2.4) | 0.3 (−0.3 to 1.1) | .47 | |

| G‐CSF | 21.2 (2.9–179.8) | 19.2 (3.0–118.9) | −22.5 (−46.6 to −10.5) | <.001 | 5.9 (1.3–51.8) | 5.7 (1.3–36.3) | −20.4 (−37.5 to −8.6) | <.001 | 2.7 (0.9–6.2) | 2.7 (1.0–6.7) | −2.6 (−10.1 to 1.7) | .47 | |

| Streptococcus Group A (n = 51) | IL‐1β | 0.81 (0.40–1.69) | 0.78 (0.19–1.79) | −0.36 (−0.70 to −0.05) | .049 | 0.31 (0.12–0.80) | 0.55 (0.16–0.83) | 0.06 (−0.23 to 0.39) | .67 | 0.28 (0.12–0.77) | 0.40 (0.12–0.83) | 0.08 (−0.16 to 0.35) | .51 |

| TNF‐α | 39.3 (26.2–64.1) | 36.6 (24.6–64.5) | −1.3 (−4.3 to 1.5) | .48 | 29.7 (17.4–50.7) | 29.0 (17.3–51.7) | 1.5 (−2.5 to 4.7) | .49 | 19.7 (14.7–34.1) | 23.7 (14.8–35.7) | 1.6 (−2.0 to 5.8) | .50 | |

| IL‐6 | 184.3 (60.6–595.7) | 172.6 (45.2–454.9) | −29.5 (−79.9 to −8.0) | .01 | 49.7 (25.2–162.0) | 45.7 (22.1–136.5) | −7.6 (−26.0 to −2.4) | .01 | 19.9 (12.1–35.9) | 18.2 (10.8–21.3) | −2.1 (−4.2 to −0.5) | .03 | |

| IL‐10 | 5.5 (1.5–17.8) | 5.8 (1.3–18.6) | −1.0 (−3.3 to 0.3) | .22 | 1.3 (0.3–4.6) | 2.3 (0.7–4.7) | 0.3 (−1.5 to 1.7) | .79 | 0.3 (0.2–1.6) | 1.3 (0.3–2.6) | 1.4 (−0.3 to 3.3) | .18 | |

| G‐CSF | 261.7 (38.7–1778.5) | 127.3 (26.3–1771.0) | −106.9 (−346.7 to −35.6) | .003 | 79.0 (12.8–185.9) | 45.3 (8.7–159.6) | −51.4 (−101.1 to −25.6) | .002 | 4.7 (2.0–62.0) | 4.7 (1.8–33.4) | −10.9 (−25.8 to −1.9) | .04 | |

| Anaerobic (n = 78) | IL‐1β | 0.68 (0.23–1.31) | 0.78 (0.32–1.60) | 0.03 (−0.17 to 0.25) | .68 | 0.55 (0.21–1.18) | 0.40 (0.21–0.97) | −0.12 (−0.33 to 0.06) | .61 | 0.51 (0.16–1.08) | 0.44 (0.22–1.16) | 0.10 (−0.2 to 0.38) | .58 |

| TNF‐α | 34.3 (20.6–54.4) | 29.3 (18.5–55.8) | −3.0 (−6.0 to −0.4) | .13 | 21.03 (15.7–37.4) | 23.8 (15.0–39.3) | −0.67 (−2.8 to 1.4) | .78 | 17.9 (9.5–30.7) | 17.5 (10.4–27.8) | 0.91 (−0.8 to 4.8) | .46 | |

| IL‐6 | 84.0 (37.1–202.4) | 75.2 (35.6–174.4) | −6.8 (−18.7 to 0.1) | .18 | 43.0 (26.1–81.6) | 49.5 (23.3–73.6) | −2.0 (−5.3 to 1.0) | .39 | 26.7 (13.4–40.1) | 23.7 (15.7–44.1) | 1.0 (−1.2 to 3.9) | .56 | |

| IL‐10 | 3.9 (0.3–18.5) | 3.2 (0.3–13.5) | −1.8 (−4.6 to −0.3) | .13 | 0.52 (0.2–3.7) | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 0.57 (−0.3 to 1.6) | .39 | 0.3 (0.2–2.4) | 0.3 (0.2–2.4) | 0.4 (−0.7 to 2.9) | .61 | |

| G‐CSF | 22.6 (2.5–79.3) | 16.3 (3.1–69.5) | −10.6 (−24.5 to 0.4) | .18 | 4.9 (1.2–24.5) | 4.3 (1.3–21.1) | −4.7 (−14.1 to 1.3) | .25 | 2.5 (0.9–4.9) | 2.5 (1.0–5.9) | 6.9 (0.2–20.2) | .12 | |

Concentrations shown in pg/ml. Values presented for all HBO2‐treated patients (1 treatment: n = 209; 2 treatments: n = 190 and 3 treatments: n = 164 patients) sub‐groups of patients with presence of either Group A‐Streptococcus (1 treatment; n = 51. 2 treatments; n = 45 and 3 treatments; n = 36) or anaerobic species (1 treatment; n = 78. 2 treatments; n = 70 and 3 treatments; n = 61), in tissue and/or blood. Data are presented as group medians and interquartile range. Paired analyses (before/after HBO2) with median differences (95% CI) evaluated by Wilcoxon Signed‐Rank Test with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p‐values due to multiple comparisons.

Abbreviation: MD, Median difference.

Subgroup analyses of patients with Group A‐Streptococcus revealed a significant and consistent decrease in IL‐6 both after the first, second, and third HBO2 treatment compared to the level before the, respectively, treatment (Table 2). Furthermore, significant differences in IL‐1β after the first HBO2 treatment and G‐CSF at both first, second, and third HBO2 treatment were observed (Table 2). In analyses of patients with anaerobic species, no significant changes were observed (Table 2).

3.2. Cytokines and NSTI severity

Patients with NSTI and septic shock at admission (n = 114, 47%) had significantly higher baseline cytokine levels compared to non‐shock patients (Table 3). Likewise, patients receiving RRT within the first 7 days from admission had significantly higher baseline values compared to non‐RRT patients (Table 3). However, no significant differences were found between patients receiving amputation compared to non‐amputated NSTI patients (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Cytokine concentrations at admission (top) and longitudinal concentrations (AUC) during first 3 days from admission (bottom)

| IL‐1β | TNF‐α | IL‐6 | IL‐10 | G‐CSF | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | ||||||||||

| Shock | 1.39 (0.64–3.89) | p < .001 | 51.9 (31.6–89.1) | p < .001 | 542.9 (143.0–3,809.1) | p < .001 | 21.7 (9.7–63.7) | p < .001 | 246.3 (33.2–5,171.0) | p < .001 |

| Non‐shock | 0.61 (0.22–1.35) | 23.6 (14.2–47.9) | 57.5 (30.0–169.6) | 3.3 (0.3–10.0) | 11.8 (3.3–51.1) | |||||

| RRT | 1.57 (0.76–3.68) | p = .009 | 64.1 (39.8–137.0) | p < .001 | 1145.0 (193.1–7,495.2) | p < .001 | 28.0 (9.7–113.3) | p = .002 | 709.4 (37.4–5,456.1) | p < .001 |

| Non‐RRT | 0.82 (0.31–1.90) | 36.5 (16.6–69.6) | 140.5 (54.5–462.6) | 9.5 (2.3–26.9) | 34.7 (3.7–245.7) | |||||

| Amputated | 0.83 (0.26–1.9) | p = .99 | 39.9 (16.7–97.4) | p = .49 | 353.6 (49.3–2,361.9) | p = .09 | 21.5 (5.6–36.7) | p = .12 | 102.8 (7.3–5,641.4) | p = .25 |

| Non‐amputated | 0.84 (0.36–2.0) | 36.3 (18.1–60.8) | 113.4 (42.8–517.2) | 8.6 (1.4–24.7) | 34.6 (5.5–271.9) | |||||

| Longitudinal AUC | ||||||||||

| Shock | 2.04 (0.97–3.72) | p = .007 | 95.5 (51.5–160.4) | p < .001 | 543.9 (131.2–2,794.2 | p < .001 | 18.3 (8.0–42.2) | p < .001 | 175.5 (24.1–4,220.2) | p < .001 |

| Non‐shock | 1.33 (0.75–2.47 | 53.7 (34.6–89.2) | 138.7 (67.7–291.2) | 4.1 (1.4–12.7) | 15.5 (7.3–58.0) | |||||

| RRT | 2.80 (1.47–5.79) | p = .007 | 160.9 (107.0–210.4) | p < .001 | 1214.5 (280.9–6,884.5) | p = .001 | 40.1 (12.0–146.1) | p < .001 | 780.5 (64.2–13,254.5) | p < .001 |

| Non‐RRT | 1.71 (0.72–3.19) | 71.0 (43.2–272.7) | 247.8 (130.9–545.6) | 10.3 (3.0–28.5) | 34.0 (8.8–234.5) | |||||

| Amputated | 2.04 (0.66–3.19) | p = 0.56 | 83.0 (36.3–159.3) | p = .45 | 364.0 (117.3–2016.0) | p = .08 | 19.2 (3.9–41.1) | p = .10 | 87.8 (8.1–3,471.0) | p = .27 |

| Non‐amputated | 1.59 (0.77–3.03) | 68.6 (38.9–114.1) | 206.6 (80.1–644.3) | 8.0 (1.8–24.8) | 33.6 (8.9–244.4)s | |||||

Concentrations in pg/ml. Results presented according to patients presenting with shock at admission (114 shock vs 128 non‐shock), receiving RRT within first 7 days (42 RRT vs. 200 non‐RRT) and receiving amputations within first 7 days (33 amputated vs. 79 non‐amputated; only patients with NSTI located to the extremities (n = 112) were included). Septic shock defined as lactate >2 mmol/L and use of vasopressor or inotrope. Data are presented as medians (interquartile range, IQR). Statistical comparisons evaluated by Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; RRT, renal‐replacement therapy.

All baseline cytokines concentration showed a significant correlation with lactate, SAPS II, and SOFA score (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Spearman rank correlation between severity of disease and baseline biomarker level

| SAPS II | SOFA | Lactate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rho | p | Rho | p | Rho | p | |

| IL‐1β | 0.23 | .001 | 0.25 | <.001 | 0.41 | <.001 |

| TNF‐α | 0.38 | <.001 | 0.46 | <.001 | 0.50 | <.001 |

| IL‐6 | 0.32 | <.001 | 0.52 | <.001 | 0.64 | <.001 |

| IL‐10 | 0.32 | <.001 | 0.46 | <.001 | 0.55 | <.001 |

| G‐CSF | 0.24 | .001 | 0.40 | <.001 | 0.54 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Examining longitudinal concentrations by AUC; IL‐1β, TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐10, and G‐CSF showed a median AUC of 1.72 (0.77–3.10), 69.0 (38.8–124.3), 224.8 (81.9–786.2), 9.5 (2.0–29.1), and 35.5 (8.7–310.3), respectively. In longitudinal analyses, patients presenting with shock at admission had significantly higher AUC in all cytokines compared to non‐shock patients (Table 3). This was also found in patients receiving RRT compared to non‐RRT patients (Table 3). No differences were found in longitudinal AUC between patients receiving amputation and non‐amputated patients (Table 3).

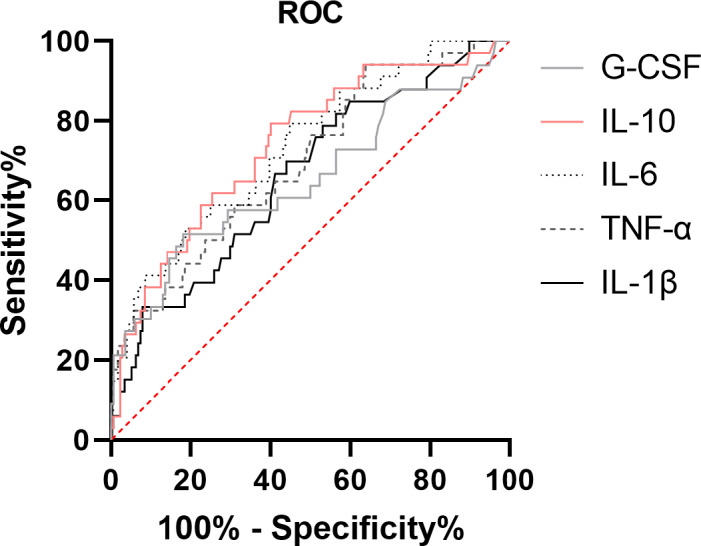

3.3. Cytokines and 30‐day mortality

All cytokines showed good moderate ROC‐AUC (Figure 3) with IL‐10 demonstrating the highest AUC of 0.74 (95% CI 0.64–0.84) (Table 5). The optimal cut‐off point (Youden Index) for IL‐1β, TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐10, and G‐CSF were found to be 0.86, 20.86, 133.5, 10.1, and 446.9, respectively. In unadjusted logistic regression models, both IL‐1β, TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐10, and G‐CSF showed to be associated with 30‐day mortality (Table 6). These results were unaltered when adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidity, however, only G‐CSF was statistically significantly associated with 30‐day mortality when additionally adjusted for SOFA score (Table 6). Accuracy for prediction of 30‐day mortality according to high versus low baseline cytokine levels are presented in Table 5.

FIGURE 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of 30‐day mortality in patients with necrotizing soft‐tissue infections for the pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines

TABLE 5.

Accuracy of high baseline biomarker (defined by being above the optimal cut‐off point) level in predicting 30‐day mortality

| IL‐1β | TNF‐α | IL‐6 | IL‐10 | G‐CSF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.71 (0.51–0.85) | 0.94 (0.80–0.99) | 0.79 (0.62–0.91) | 0.79 (0.62–0.91) | 0.52 (0.34–0.69) |

| Specificity | 0.56 (0.45–0.63) | 0.34 (0.27–0.42) | 0.55 (0.47–0.62) | 0.60 (0.52–0.67) | 0.81 (0.74–0.87) |

| PPV | 0.24 (0.16–0.33) | 0.22 (0.15–0.29) | 0.25 (0.17–0.35) | 0.28 (0.19–0.37) | 0.35 (0.22–0.50) |

| NPV | 0.91 (0.84–0.96) | 0.97 (0.89–1.00) | 0.93 (0.86–0.97) | 0.94 (0.88–0.97) | 0.90 (0.84–0.94) |

| AUC‐ROC | 0.67 (0.56–0.77) | 0.70 (0.59–0.80) | 0.73 (0.63–0.83) | 0.74 (0.64–0.84) | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) |

Data are presented as fractions (95% confidence interval).

Abbreviations: AUC‐ROC, area under the receiver operating characteristics curve; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

TABLE 6.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of 30‐day mortality based on low versus high baseline cytokine levels according to the optimal cut‐off values

| pg/ml | Unadjusted | Adjusted analysis: age, sex and comorbidities | Adjusted analysis: age, sex, comorbidities and SOFA score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| IL‐1β | |||||||||

| Low ≤0.86 | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | ||||||

| High >0.86 | 3.05 | 1.41–7.03 | .006 | 3.54 | 1.56–8.64 | .004 | 2.60 | 0.99–7.35 | .059 |

| TNF‐α | |||||||||

| Low ≤20.86 | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | ||||||

| High >20.86 | 8.41 | 2.44–53.01 | .004 | 7.20 | 2.03–45.97 | .009 | 3.42 | 0.77–2.52 | .15 |

| IL‐6 | |||||||||

| Low ≤133.5 | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | ||||||

| High >133.5 | 4.63 | 2.01–12.05 | <.001 | 4.42 | 1.87–11.82 | .001 | 1.32 | 0.45–4.05 | .61 |

| IL‐10 | |||||||||

| Low ≤10.1 | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | ||||||

| High >10.1 | 5.76 | 2.50–15.01 | <.001 | 5.80 | 2.43–15.63 | <.001 | 2.39 | 0.85–7.22 | .11 |

| G‐CSF | |||||||||

| Low ≤446.9 | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | 1 Ref. | ||||||

| High >446.9 | 4.58 | 2.09–10.13 | <.001 | 6.16 | 2.58–15.32 | <.001 | 2.83 | 1.01–8.00 | .047 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment.

Longitudinal AUC analyses showed significant differences between survivors and non‐survivors according to IL‐6 (206.6 [74.7–544.8] vs. 547.6 [114.0–4,370.3], p = 0.007) and IL‐10 (7.09 [1.68–23.09] vs. 20.96 [5.32–142.20], p = 0.001). However, no differences were found according to IL‐1β (1.65 [0.76–2.87] vs. 1.81 [0.78–3.41], p = 0.63), TNF‐α (68.8 [40.7–120.3] vs. 71.9 [29.9–138.9], p = 0.95) or G‐CSF (35.5 [8.9–233.6] vs. 87.8 [8.7–9,853.7], p = 0.17).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study evaluating several pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines in patients with NSTI, IL‐6 levels were decreased after adjunctive HBO2 treatment in patients with Group A‐Streptococcus, and decreased G‐CSF levels in general. Moreover, we found high levels of IL‐1β, TNF‐α, IL‐6, IL‐10, and G‐CSF to be associated with severity of disease as represented by higher cytokine levels among patients with septic shock and positive correlations with SAPS II, SOFA score, and lactate. High baseline G‐CSF demonstrated to be an independent risk factor of 30‐day mortality.

Cytokine assessment may be a valuable tool for the treating clinician and may be useful for prognosis prediction and clinical decision‐making (Bozza et al., 2005; Pierrakos et al., 2020). In patients with severe sepsis and septic shock; IL‐1β, IL‐6, and G‐CSF have demonstrated good accuracy for predicting early mortality while IL‐6 and G‐CSF showed to be predictive of worsening of organ dysfunction (Bozza et al., 2007). In addition, both IL‐1β, IL‐6, and G‐CSF have shown to be elevated in septic non‐survivors compared to survivors during the first 3 days upon admission (Mera et al., 2011). Interestingly, cytokine network analyses have revealed a network formed by IL‐1β, IL‐6, and IL‐10 during the first day of sepsis, suggesting that these cytokines may take a crucial role in the acute phase of sepsis (Matsumoto et al., 2018). The present results demonstrated that G‐CSF was significantly associated with 30‐day mortality in patients with NSTI and is in accordance with the present literature in septic patients. However, of ample notice, G‐CSF and IL‐1β ROC‐AUC values in predicting 30‐day mortality did not reach an acceptable level of above 0.7, indicating that the accuracy of prediction should be cautiously interpreted (Mandrekar, 2010). Of interests, IL‐1β has previously demonstrated to be a predictor of 30‐day mortality in a smaller part of the present cohort (n = 159; Hansen et al., 2017), but in the present study including the entire Danish cohort (n = 242); IL‐1β did not reach a statistically significant level in predicting 30‐day mortality.

Cytokines have been profoundly studied in septic patients (Pierrakos et al., 2020). However, only a few studies exist on cytokine profiles in patients with NSTI indicating that particular IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐10, and IL‐18 may take a crucial part in NSTI pathophysiology (Hansen et al., 2017; Lungstras‐Bufler et al., 2004; Rodriguez et al., 2006). In sepsis, an excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines may cause collateral damage to the endothelium layer and progress into systemic inflammatory response syndrome, multiple organ failure with a substantially high risk of morbidity and mortality (Levi & Poll, 2017; Levi & Van Der Poll, 2013). In that context, the rapid and severe cause of disease among patients with NSTI may reflect a disproportional and excessive proinflammatory response caused by toxin production and cytokine activation (Bonne & Kadri, 2017; Johansson et al., 2010; Norrby‐Teglund et al., 2001). However, the concept of an initial uncontrolled proinflammatory response followed by an anti‐inflammatory phase seems to be a simplified model, and increasing evidence indicates that the host response is dependent on numerous complex, dynamic, and concomitant pathogen and host‐immune defense mechanisms such as the bacterial virulence and microbial load (Schulte et al., 2013; Van Der & Opal, 2008).

Sepsis‐mediated endothelial damage increases IL‐6 proliferation that causes soluble IL‐6 to bind to its receptor (IL‐6R), forming the IL‐6/IL‐6R complex (Tanaka et al., 2016). The IL‐6/IL‐6R complex activates glycoprotein 130 (Jones et al., 2011)—a signal‐transducing component placed on various tissues and cells including the endothelium—consequently triggering various of downstream effects including the production of acute‐phase proteins (Heinrich et al., 1990), inducement of complement C3 and C5a receptor (Tanaka et al., 2016), initiation of coagulation through tissue factor activation (Neumann et al., 1997) and activates the endothelium to produce IL‐6 and enhance intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1) expression resulting in increased leukocyte recruitment (Romano et al., 1997; Tanaka et al., 2016). IL‐1β, a powerful proinflammatory cytokine primarily created by activated macrophages and monocytes, acts on a variety of immune cells including the endothelium, amplifying the inflammatory process by release of proinflammatory cytokines—such as IL‐6—and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (Schulte et al., 2013). In this context, it may be of importance to note, that both ICAM‐1 and IL‐6 are modified by HBO2 treatment in experimental sepsis (Bærnthsen et al., 2017; Buras et al., ,2000, 2006; Halbach et al., 2019). Some evidence indicates that G‐CSF—a hematopoietic‐cell growth factor—is involved in sepsis pathogenesis and has crucial functions on mature myeloid cells and the innate immune system during inflammation (Hamilton, 2008; Roberts & Roberts, 2005). G‐CSF is markedly increased during severe infections (Roberts & Roberts, 2005), and a linkage between colony‐stimulating factors and expression of IL‐1β and TNF‐α has earlier been suggested. The present result demonstrating high baseline G‐CSF as an independent risk factor of 30‐day mortality, suggests G‐CSF may help guide the treating physician in risk stratification as high G‐CSF at admission indicates an increased risk of dying within day 30.

It has become well‐accepted that sepsis is not a linear process (Bozza et al., 2005). Consequently, studies only assessing cytokines at admission may lack important information on pathophysiological understanding and its impact on clinical progression and outcomes. Therefore, in an effort of evaluating the overall inflammatory status, we addressed the cytokine level from admission throughout the following 3 days as AUC. To our knowledge, no studies have—to date—examined the kinetics of cytokines in NSTI, and only a few studies with septic patients have evaluated the progress of cytokines during the first days from admission (Matsumoto et al., 2018; Mera et al., 2011). In general, these studies agree with the present results demonstrating markedly highest cytokine concentrations at admission with a substantial decrease the following days. Yet, an inverse development has been observed in sepsis non‐survivors according to IL‐1β and G‐CSF demonstrating gradually increased values during the first 3 days from admission compared to sepsis survivors (Mera et al., 2011). However, in patients with NSTI we were unable to detect any differences between NSTI survivors and non‐survivors according to longitudinal AUC analyses of IL‐1β and G‐CSF.

In a large multicenter observational study including 583 patients with severe sepsis, it was demonstrated that patients with high levels of IL‐6 and IL‐10 had markedly increased risk of dying (hazard ratio of 20.52) (Kellum et al., 2007). Interestingly, these findings seem in accordance with the present longitudinal results of patients with NSTI; indicating that mortality is highest when both pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines are high.

HBO2 treatment induces several immunomodulatory effects that may well explain the observed cytokine fluctuations before and after HBO2 treatment. Studies of experimental sepsis have indicated that HBO2 treatment exerts its antimicrobial effect by enhancement of IL‐10, which lowers IL‐6 and thereby reduces the overall mortality in HBO2‐treated animals (Bærnthsen et al., 2017; Buras et al., 2006). However, we were unable to detect any fluctuations of IL‐10 after HBO2 treatment, but this discrepancy may well be explained by our time of blood sampling immediately after treatment which does not respect the less rapid kinetics of IL‐10 (Khatri & Caligiuri, 1998). Of notice, patients with Group A‐Streptococcus NSTI have higher rates of septic shock (Madsen et al., 2019), and HBO2 treatment has shown its greatest effect in the most severely ill NSTI patients (Devaney et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2014); therefore, the present observed attenuation of IL‐6 subsequently after HBO2 treatment in patients with Group A‐Streptococcus may well reflect this clinical effect with a more pronounced immunomodulatory effect in the most severely ill patients. Furthermore, in patients with Crohn's disease HBO2 treatment has shown to modulate the proinflammatory response by an initial elevation of IL‐1 but during courses of HBO2 decreasing IL‐1; indicating that prolonged HBO2 treatment may initially exhaust monocytes of stored IL‐1 subsequently leading to an inhibition of cytokine production and/or secretion (Weisz et al., 1997). Interestingly, this HBO2‐mediated immunosuppressive effect does not seem to reduce the phagocytic activity of the macrophages and their bacterial defense mechanisms remain intact (Inamoto et al., 1991). G‐CSF has sparsely been investigated in relation to HBO2 treatment, but in patients with carbon monoxide poisoning courses of HBO2 treatment has shown to initial increase G‐CSF subsequent decreasing G‐CSF afterward (Schnittger et al., 2004). We found a significant reduction in G‐CSF immediately after first and second HBO2 treatment compared to samples before treatment which may be central in the suggested HBO2‐mediated immunomodulatory effect by G‐CSF’s inhibition on IL‐1β expression and the innate immune response. In that context, we demonstrated a reduction of IL‐1β after first HBO2 treatment in patients with Group A‐Streptococcus.

Of great notice, the present study does not include a matched control group of patients not receiving HBO2 treatment, thus we cannot definitely ascertain that the observed fluctuations are due to the treatment itself or could represent a general improvement in the clinical condition. However, the relatively short time period between HBO2 treatment and blood sampling increases the confidence that the observed effects are mediated by the treatment and not the natural cause of declination caused by gradual improvement of the patient's condition.

A series of strengths to the present study exists. First, the substantial‐high follow‐up rate of >98% increases the validity of the present results. Second, the broad inclusion and limited exclusion criteria strengthen the study's generalizability. Third, we measured cytokine concentrations in a longitudinal design thus increasing the information of the overall inflammatory response over time. Last, we analyzed a limited number of cytokines and thereby reduced the risk of chance findings. Limitations of the study include the absence of a matched control group of patients not receiving HBO2 treatment, and that the laboratory analysts were not blinded for patient outcome.

In conclusion, our study suggests an immune‐modulating effect of HBO2 treatment in NSTI patients as indicated by decreasing IL‐6 in patients with Group A‐Streptococcus and decreasing G‐CSF in general. Secondly, that high baseline levels of proinflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokines are associated with severity of disease and high G‐CSF at admission is associated with 30‐day mortality. Future research on the possible derived effects on the immune response during HBO2 treatments in general and in NSTI patients specifically are much warranted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interests, financial, or otherwise declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study planning (MH, PG, OH), laboratory analysis (MH and Biotechnician Bettina Eide Holm), data analyses (MH, OH), results interpretation (MH, PG, MM, OH), manuscript drafting (MH, OH), revision and approval of the final version of the manuscript (MH, PG, MM, OH).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Biotechnician Bettina Eide Holm, Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Department of Clinical Immunology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, for valuable help with the laboratory analyses. The authors thank project nurse Martin Forchammer for biobank assistance and coordination.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet) Research Grant (grant number R167‐A7352‐B3897), which included a research fellowship for MH. Moreover, the study was supported by Wedellsborgs Fund and the projects of PERMIT (grant number 8113‐00009B) funded by Innovation Fund Denmark and EU Horizon 2020 under the frame of ERA PerMed (project 2018‐151) and PERAID (grant number 8114‐00005B) funded by Innovation Fund Denmark and Nordforsk (project no. 90456). The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme: (FP7/2007‐2013) under the grant agreement 305340 (INFECT project).

REFERENCES

- Anderson, C. A. , & Jacoby, I. (2019). Necrotizing soft tissue infections. In Moon R. E. (Ed.), Hyperbaric oxygen therapy indications (pp. 239–263). Best Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bærnthsen, N. F. , Hansen, M. B. , Wahl, A. M. , Simonsen, U. , & Hyldegaard, O. (2017). Treatment with 24 h‐delayed normo‐ and hyperbaric oxygenation in severe sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture in rats. Journal of Inflammation (United Kingdom), 14, 1–9. 10.1186/s12950-017-0173-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonne, S. , & Kadri, S. (2017). Evaluation and management of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 31, 497–511. 10.1016/j.idc.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza, F. A. , Bozza, P. T. , Castro Faria Neto, H. C. (2005). Beyond sepsis pathophysiology with cytokines: What is their value as biomarkers for disease severity? Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 100, 217–221. 10.1590/S0074-02762005000900037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza, F. A. , Salluh, J. I. , Japiassu, A. M. , Soares, M. , Assis, E. F. , Gomes, R. N. , Bozza, M. T. , Castro‐Faria‐Neto, H. C. , & Bozza, P. T. (2007). Cytokine profiles as markers of disease severity in sepsis: A multiplex analysis. Critical Care, 11, 1–8. 10.1186/cc5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buras, J. A. , Holt, D. , Orlow, D. , Belikoff, B. , Pavlides, S. , & Reenstra, W. R. (2006). Hyperbaric oxygen protects from sepsis mortality via an interleukin‐10‐dependent mechanism. Critical Care Medicine, 34, 2624–2629. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239438.22758.E0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buras, J. A. , Stahl, G. L. , Svoboda, K. K. H. , & Reenstra, W. R. (2000). Hyperbaric oxygen downregulates ICAM‐1 expression induced by hypoxia and hypoglycemia: The role of NOS. American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology, 278, 292–302. 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.c292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camporesi, E. M. , & Bosco, G. (2014). Mechanisms of action of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine, 41, 247–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, B. , Frawley, G. , Frawley, L. , & Pilcher, D. (2015). Necrotising soft tissue infections: The effect of hyperbaric oxygen on mortality. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 43, 685–692. 10.1177/0310057X1504300604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elm, E. , Altman, D. , Egger, M. , Stuart, J. , Gøtzsche, P. , & Vandenbroucke, J. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet, 370, 1453–1457. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen, T. W. , Kopari, N. M. , Pham, T. N. , & Evans, H. L. (2014). Necrotizing soft tissue infections: Review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes. Current Problems in Surgery, 51, 344–362. 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach, J. L. , Prieto, J. M. , Wang, A. W. , Hawisher, D. , Cauvi, D. M. , Reyes, T. , Okerblom, J. , Ramirez‐Sanchez, I. , Villarreal, F. , Patel, H. H. , Bickler, S. W. , Perdrizet, G. A. , & De Maio, A. (2019). Early hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves survival in a model of severe sepsis. American Journal of Physiology‐Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 317, R160–R168. 10.1152/ajpregu.00083.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. A. (2008). Colony‐stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nature Reviews Immunology, 8, 533–544. 10.1038/nri2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M. B. , Rasmussen, L. S. , Svensson, M. , Chakrakodi, B. , Bruun, T. , Madsen, M. B. , Perner, A. , Garred, P. , Hyldegaard, O. , Norrby‐Teglund, A. , Nekludov, M. , Arnell, P. , Rosén, A. , Oscarsson, N. , Karlsson, Y. , Oppegaard, O. , Skrede, S. , Itzek, A. , Wahl, A. M. , … Nedrebø, T. (2017). Association between cytokine response, the LRINEC score and outcome in patients with necrotising soft tissue infection: A multicentre, prospective study. Scientific Reports 7. 10.1038/srep42179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedetoft, M. , Madsen, M. , Madsen, L. , & Hyldegaard, O. (2020). Incidence, comorbidity and mortality in patients with necrotising soft‐tissue infections, 2005–2018: A Danish nationwide register‐based cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 10, e041302. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, P. C. , Castell, J. V. , & Andus, T. (1990). Interleukin‐6 and the acute phase response. The Biochemical Journal, 265, 621–636. 10.1042/bj2650621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamoto, Y. , Okuno, F. , Saito, K. , Tanaka, Y. , Watanabe, K. , Morimoto, I. , Yamashita, U. , & Eto, S. (1991). Effect of hyperbaric oxygenation on macrophage function in mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 179, 886–891. 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91901-n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P. Ø. , Møller, S. A. , Lerche, C. J. , Moser, C. , Bjarnsholt, T. , Ciofu, O. , Faurholt‐Jepsen, D. , Høiby, N. , & Kolpena, M. (2019). Improving antibiotic treatment of bacterial biofilm by hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Biofilm, 1, 1–4. 10.1016/j.bioflm.2019.100008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, L. , Thulin, P. , Low, D. E. , & Norrby‐Teglund, A. (2010). Getting under the skin: The immunopathogenesis of Streptococcus pyogenes deep tissue infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 51, 58–65. 10.1086/653116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. A. , Scheller, J. , & Rose‐John, S. (2011). Therapeutic strategies for the clinical blockade of IL‐6/gp130 signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 121, 3375–3383. 10.1172/JCI57158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum, J. A. , Kong, L. , Fing, M. P. , Weissfeld, L. A. , Yealy, D. M. , Pinsky, M. R. , Fine, J. , Krichevsky, A. , Delude, R. L. , & Angus, D. (2007). Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167, 1655–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri, V. , & Caligiuri, M. (1998). Interleukin 10 and its Receptor. Encyclopedia of Immunology, 1475–1478. [Google Scholar]

- Kolpen, M. , Mousavi, N. , Sams, T. , Bjarnsholt, T. , Ciofu, O. , Moser, C. , Kuhl, M. , Hoiby, N. , & Jensen, P. O. (2016). Reinforcement of the bactericidal effect of ciprofloxacin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm by hyperbaric oxygen treatment. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 47, 163–167. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, K. , Kuttila, K. , & Niinikoski, J. (2000). Tissue gas tensions in patients with necrotising fasciitis healthy controls during treatment with hyperbaric oxygen: A clinical study. European Journal of Surgery, 166, 530–534. 10.1080/110241500750008583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerche, C. J. , Christophersen, L. J. , Kolpen, M. , Nielsen, P. R. , Trøstrup, H. , Thomsen, K. , Hyldegaard, O. , Bundgaard, H. , Jensen, P. , Høiby, N. , & Moser, C. (2017). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy augments tobramycin efficacy in experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 50, 406–412. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett, D. , Bennett, M. H. , & Millar, I. (2015). Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for necrotizing fasciitis. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 1, CD007937. 10.1002/14651858.CD007937.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi, M. , & Van Der Poll, T. (2013). Endothelial injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Medicine, 39, 1839–1842. 10.1007/s00134-013-3054-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi, M. , & van der Poll, T. (2017). Coagulation and sepsis. Thrombosis Research, 149, 38–44. 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lungstras‐Bufler, K. , Bufler, P. , Abdullah, R. , Rutherford, C. , Endres, S. , Abraham, E. , Dinarello, C. A. , & Rodriguez, R. M. (2004). High cytokine levels at admission are associated with fatal outcome in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. European Cytokine Network, 15, 135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M. B. , Skrede, S. , Bruun, T. , Arnell, P. , Rosén, A. , Nekludov, M. , Karlsson, Y. , Bergey, F. , Saccenti, E. , Martins dos Santos, V. A. P. , Perner, A. , Norrby‐Teglund, A. , & Hyldegaard, O. (2018). Necrotizing soft tissue infections – A multicentre, prospective observational study (INFECT): protocol and statistical analysis plan. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 62(2), 272–279. 10.1111/aas.13024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, M. B. , Skrede, S. , Perner, A. , Arnell, P. , Nekludov, M. , Bruun, T. , Karlsson, Y. , Hansen, M. B. , Polzik, P. , Hedetoft, M. , Rosén, A. , Saccenti, E. , Bergey, F. , Sontos, V. A. P. , INFECT Study Group , Norrby‐Teglund, A. , & Hyldegaard, O. (2019). Patient’s characteristics and outcomes in necrotising soft‐tissue infections: Results from a Scandinavian, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine, 45, 1241–1251. 10.1007/s00134-019-05730-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar, J. N. (2010). Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 5, 1315–1316. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, D. , Marroni, A. , & Kot, J. (2017). Tenth European Consensus Conference on Hyperbaric Medicine: Recommendations for accepted and non‐accepted clinical indications and practice of hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine 47, 24–32. 10.28920/dhm47.1.24-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, H. , Ogura, H. , Shimizu, K. , Ikeda, M. , Hirose, T. , Matsuura, H. , Kang, S. , Takahashi, K. , Tanaka, T. , & Shimazu, T. (2018). The clinical importance of a cytokine network in the acute phase of sepsis. Scientific Reports, 8, 1–4. 10.1038/s41598-018-32275-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memar, M. Y. , Ghotaslou, R. , Samiei, M. , & Adibkia, K. (2018). Antimicrobial use of reactive oxygen therapy: Current insights. Infection and Drug Resistance, 11, 567–576. 10.2147/IDR.S142397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memar, M. Y. , Yekani, M. , Alizadeh, N. , & Baghi, H. B. (2019). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: Antimicrobial mechanisms and clinical application for infections. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 109, 440–447. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mera, S. , Tatulescu, D. , Cismaru, C. , Bondor, C. , Slavcovici, A. , Zanc, V. , Carstina, D. , & Oltean, M. (2011). Multiplex cytokine profiling in patients with sepsis. APMIS, 119, 155–163. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M. S. (2010). Diagnosis and management of necrotising fasciitis: A multiparametric approach. Journal of Hospital Infection, 75, 249–257. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, F. J. , Ott, I. , Marx, N. , Luther, T. , Kenngott, S. , Gawaz, M. , Kotzsch, M. , & Schömig, A. (1997). Effect of human recombinant interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐8 on monocyte procoagulant activity. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 17, 3399–3405. 10.1161/01.atv.17.12.3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrby‐Teglund, A. , Thulin, P. , Gan, B. S. , Kotb, M. , McGeer, A. , Andersson, J. , & Low, D. E. (2001). Evidence for superantigen involvement in severe group a streptococcal tissue infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 184, 853–860. 10.1086/323443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S. , Bai, X. , Wang, F. , Jiang, M. , Wang, G. , Sun, B. , Kong, R. , Guo, Z. , Zhou, Y. , & Song, Z. (2013). The apoptosis of peripheral blood lymphocytes promoted by hyperbaric oxygen treatment contributes to attenuate the severity of early stage acute pancreatitis in rats. Apoptosis, 19, 58–75. 10.1007/s10495-013-0911-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakos, C. , Velissaris, D. , Bisdorff, M. , Marshall, J. C. , & Vincent, J. (2020). Biomarkers of sepsis: Time for a reappraisal. Critical Care, 24, 287. 10.1186/s13054-020-02993-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrakos, C. , & Vincent, J. L. (2010). Sepsis biomarkers: A review. Critical Care, 14, 1–18. 10.1186/cc8872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A. W. , & Roberts, A. W. (2005). G‐CSF: A key regulator of neutrophil production, but that’s not all! Growth Factors, 23, 33–41. 10.1080/08977190500055836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R. M. , Abdullah, R. , Miller, R. , Barry, L. , Lungstras‐Bufler, K. , Bufler, P. , Dinarello, C. A. , & Abraham, E. (2006). A pilot study of cytokine levels and white blood cell counts in the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24, 58–61. 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano, M. , Sironi, M. , Toniatti, C. , Polentarutti, N. , Fruscella, P. , Ghezzi, P. , Faggioni, R. , Luini, W. , van Hinsbergh, V. , Sozzani, S. , Bussolino, F. , Poli, V. , Ciliberto, G. , & Mantovani, A. (1997). Role of IL‐6 and its soluble receptor in induction of chemokines and leukocyte recruitment. Immunity, 6, 315–325. 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80334-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger, V. , Rosendahl, K. , Lind, F. , & Palmblad, J. (2004). Effects of carbon monoxide poisoning on neutrophil responses in patients treated with hyperbaric oxygen. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 52, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, W. , Bernhagen, J. , & Bucala, R. (2013). Cytokines in sepsis: Potent immunoregulators and potential therapeutic targets — An updated view. Meditators of Inflammation, 165974, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J. J. , Psoinos, C. , Emhoff, T. A. , Shah, S. A. , & Santry, H. P. (2014). Not just full of hot air: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy increases survival in cases of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Surgical Infections (Larchmt), 15, 328–335. 10.1089/sur.2012.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens, N. , Chakrakodi, B. , Shambat, S. M. , Morgan, M. , Bergsten, H. , Hyldegaard, O. , Skrede, S. , Arnell, P. , Madsen, M. B. , Johansson, L. , Juarez, J. , Bosnjak, L. , Morgelin, M. , Svensson, M. , & Norrby‐Teglund, A. (2016). Biofilm in group A streptococcal necrotizing soft tissue infections. JCI Insight, 1, 1–13. 10.1172/jci.insight.87882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh, C. R. , Pietrobon, R. , Freiberger, J. J. , Chew, S. T. , Rajgor, D. , Gandhi, M. , Shah, J. , & Moon, R. E. (2012). Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in necrotising soft tissue infections: A study of patients in the United States Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Intensive Care Medicine, 38, 1143–1151. 10.1007/s00134-012-2558-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A. M. , Best, M. J. , Francis, C. S. , Allan, B. J. , Askari, M. , & Panthaki, Z. J. (2014). Trends in the incidence and treatment of necrotizing soft tissue infections: An analysis of the national hospital discharge survey. Journal of Burn Care & Research, 35, 449–454. 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, D. L. , & Bryant, A. E. (2017). Necrotizing soft‐tissue infections. New England Journal of Medicine, 377, 2253–2265. 10.1056/NEJMra1600673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T. , Narazaki, M. , & Kishimoto, T. (2016). Immunotherapeutic implications of IL‐6 blockade for cytokine storm. Immunotherapy, 8, 959–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom, S. R. (2009). Oxidative stress is fundamental to hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Journal of Applied Physiology, 106, 988–995. 10.1152/japplphysiol.91004.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der, P. T. , & Opal, S. M. (2008). Host–pathogen interactions in sepsis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 8, 32–43. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70265-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.‐L. , & Hung, C.‐R. (2004). Role of tissue oxygen saturation monitoring in diagnosing necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 44, 222–228. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, G. , Lavy, A. , Adir, Y. , Melamed, Y. , Rubin, D. , Eidelman, S. , & Pollack, S. (1997). Modification of in vivo and in vitro TNF‐α, IL‐1, and IL‐6 secretion by circulating monocytes during hyperbaric oxygen treatment in patients with perianal Crohn’s disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 17, 154–159. 10.1023/A:1027378532003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]