Abstract

Purpose: To examine whether adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with breastfeeding behaviors.

Methods: Women in three Kaiser Permanente Northern California medical centers were screened for ACEs during standard prenatal care (N = 926). Multivariable binary and multinomial logistic regression was used to test whether ACEs (count and type) were associated with early breastfeeding at the 2-week newborn pediatric visit and continued breastfeeding at the 2-month pediatric visit, adjusting for covariates.

Results: Overall, 58.2% of women reported 0 ACEs, 19.2% reported 1 ACE, and 22.6% reported 2+ ACEs. Two weeks postpartum, 92.2% reported any breastfeeding (62.9% exclusive, 29.4% mixed breastfeeding/formula). Compared with women with 0 ACEs, those with 2+ ACEs had increased odds of any breastfeeding (odds ratio [OR] = 2.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.3–5.6) and exclusive breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum (OR = 3.0, 95% CI = 1.4–6.3). Among those who breastfed 2 weeks postpartum, 86.4% reported continued breastfeeding (57.5% exclusive, 28.9% mixed breastfeeding/formula) 2 months postpartum. ACE count was not associated with continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum. Individual ACEs were not related to breastfeeding outcomes, with the exception that living with someone who went to jail or prison was associated with lower odds of continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum.

Conclusions: ACE count was associated with greater early breastfeeding, but not continued breastfeeding, among women screened for ACEs as part of standard prenatal care. Results reiterate the need to educate and assist all women to meet their breastfeeding goals, regardless of ACE score.

Keywords: pregnancy, adverse childhood experiences, ACEs, prenatal, breastfeeding, formula, health care, screening

Introduction

Breastfeeding is associated with significant health benefits for women and their infants. Women who breastfeed have lower rates of postpartum depression, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and breast and ovarian cancer.1 Children who are breastfed are less likely to have respiratory tract infections, gastrointestinal tract infections, sudden infant death syndrome and infant mortality, allergic disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, childhood leukemia and lymphoma, and neurodevelopmental problems. Exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant's life and longer breastfeeding duration are associated with greater health benefits for mothers and their babies.1 Given the significant public health impacts, national and international guidelines recommend that mothers exclusively breastfeed their infants for the first 6 months of life with continued breastfeeding alongside food until at least 1–2 years of age.1,2

Despite the clear health benefits, not all women initiate breastfeeding, and nearly two-thirds of women stop sooner than intended.3 While breastfeeding rates have risen over the past decade, national data indicate that in 2016, only 84% of U.S. infants were breastfed at birth; 80% and 59% were breastfed or exclusively breastfed (i.e., did not use any formula) at 28 days, respectively, and only 71% and 48% were breastfed or exclusively breastfed by 3 months,4 respectively. By 6 months, rates of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding among U.S. women drop to 57% and 25%, respectively.4 Commonly reported reasons for not breastfeeding or early breastfeeding discontinuation include difficulty with lactation or latching, painful nipples or breasts, concerns about infant weight gain, unsupportive hospital policies, and lack of social or family support.3,5–7

Identifying factors associated with lower breastfeeding rates and early breastfeeding termination is critical to better identify and support mothers who may need additional help or resources to meet their initial breastfeeding goals. While it is well established that breastfeeding rates vary by sociodemographic factors, with lower rates of breastfeeding among non-Hispanic Black women, those with lower income, and younger women,1 more recent research has shown that psychosocial factors, including maternal prenatal and postpartum depression, may also contribute to lower breastfeeding rates.8–13

Another important but understudied potential risk factor for low rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration is maternal exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, neglect, parental loss, and exposure to household dysfunction. ACEs are common, with nearly two-thirds of adults having one or more ACEs.14 ACEs increase risk for mental and physical health problems during pregnancy15–18 and postpartum,19,20 which could lower the likelihood of breastfeeding initiation and continuation. Furthermore, breastfeeding may trigger memories of childhood sexual abuse21 and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder,22 which could lead to early discontinuation of breastfeeding. Conversely, women with ACEs may be more likely to breastfeed, due to potential mental health benefits of breastfeeding (e.g., less anxiety, lower depression),23 increased motivation to breastfeed,24 or as a way to heal from early childhood abuse.24

ACEs have only recently been recognized for their potential impact on breastfeeding behaviors and initial findings are mixed, with some studies indicating increased likelihood of breastfeeding initiation,25 others indicating increased likelihood of early termination of breastfeeding,26–29 and others indicating no association with breastfeeding initiation and/or duration.21,23,26,30–32 To date, most studies have focused exclusively on childhood sexual abuse, and few have examined the impact of other types of ACEs or ACE count on breastfeeding outcomes. Addressing this critical gap in the literature, the current study aimed to examine whether ACEs (count and type) are associated with rates of early breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum, and continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum, among women screened for ACEs as part of standard prenatal care. Examining how ACEs relate to breastfeeding behaviors is critical to better understand how psychosocial factors impact breastfeeding and to identify women who may need extra breastfeeding resources and support.

Methods

Study site

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a nonprofit, multispecialty health care delivery system that provides care for more than 4.3 million members in the Northern California region, with more than 40,000 live births annually across 21 hospitals.33,34 This study received approval from the KPNC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

This study combines data from two KPNC pilot studies in three medical centers that screened English-speaking pregnant women aged ≥18 years for ACEs as part of standard prenatal care at their second or third prenatal visit (typically between 14 and 23 weeks of gestation) from March 1, 2016, to June 30, 2016 (Study 1, medical centers A and B) and from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019 (Study 2, medical centers A and C). Patients were given the ACEs screening questionnaire to complete by the medical assistant in the examination room while waiting for their physician. Physicians then reviewed the questionnaires with patients and provided referrals for behavioral health services, as needed, along with an educational handout with relevant community and educational resources. Additional information about study methods and resources has been previously published.35

Participants

The study sample comprised the 1139 English-speaking pregnant women who completed the ACEs questionnaire during standard prenatal care in either Study 1 (N = 355) or Study 2 (N = 784). Sixty women who did not complete the ACEs questionnaire were excluded; they did not differ significantly from those who completed the questionnaire on age or race/ethnicity but were more likely to have a neighborhood household income below the median (69% vs. 47%, p < 0.01). Furthermore, 213 women with data on ACEs who were missing data on breastfeeding behaviors because they did not have a standard pediatric visit for their newborn between 0 and 28 days (2-week visit) and between 29 days and 12 weeks (2-month visit) were excluded. Compared with women with breastfeeding data, those excluded for missing breastfeeding data did not differ significantly on ACEs or race/ethnicity, but they were somewhat younger (23% vs. 14% were aged 18–25 years, p < 0.01) and more likely to have a neighborhood household income below the median (60% vs. 47%, p < 0.01).

Measures

We assessed ACEs before age 18 using a modified version of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire36 adapted to be appropriate for prenatal patients and easy to self-administer in a health care setting.35 Prenatal patients are brought to a private examination room alone for the initial portion of the prenatal visit. This allows discussion about sensitive topics (including weight, sexually transmitted infections, and intimate partner violence) to take place in a safe and confidential setting. The ACEs and Resilience questionnaires are completed in this confidential environment as well. In Study 1, patients responded yes (1) or no (0) to eight ACEs before age 18 (loss of parent; sexual abuse; physical abuse; emotional abuse; living with someone with a substance use problem; living with someone who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide; living with someone who went to jail or prison; and living with someone who hit, punched, beat, or threatened to harm another adult in the home) and total possible scores ranged from 0 to 8.35 Study 2 included two additional questions about exposure to neglect before age 18 (possible scores ranged from 0 to 10); however, to combine the two samples and maximize sample size for detecting associations between ACEs and breastfeeding outcomes, these additional questions were not included as they were only available for a subset of the sample. ACEs were categorized by total ACE score (0, 1, and 2+) and by individual ACE question.

Early and continued breastfeeding were defined using maternal self-reported breastfeeding (exclusive breastfeeding, mixed breastfeeding/formula, formula only) from the well-check questionnaires given at the infant's 2-week (mean [standard deviation, SD] = 15 days [2.9 days], median = 15 days, range = 2–28 days) and 2-month (mean [SD] = 62 days [5.3 days], median = 62 days, range = 35–84 days) newborn pediatric visits.

Parity at the time of the 2-week breastfeeding screening was determined from the patient's obstetric history. Self-reported living situation (categorized as living with vs. not with partner/baby's father) was based on a pregnancy circumstances questionnaire given at the first prenatal visit as part of standard prenatal care.

Depression symptoms were based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),37 which is given to pregnant patients as part of standard prenatal care. Scores range from 0 to 27 and were dichotomized into no depression (<5) versus mild, moderate, or severe depression (>5) to include subclinical levels of depression symptoms as performed in our prior studies.38

Preterm birth and mode of delivery were extracted from the obstetric electronic health record (EHR). Infants born before 37 weeks were considered to be preterm. Mode of delivery was classified as either vaginal (assisted or unassisted) or cesarean section.

Demographic characteristics were obtained from the EHR and included women's age at ACEs screening, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, Other/unknown), and neighborhood median household income based on census data.

Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages are used to describe sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, neighborhood median household income, lives with baby's father), clinical characteristics (prenatal depression, parity, mode of birth, preterm birth), and ACE count (0, 1, and 2+) and type. Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare categorical sociodemographic covariates and clinical characteristics, ACE count, and ACE type by breastfeeding outcomes.

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to compare the odds of breastfeeding at each time point by ACE count and by individual ACE type. Binary logistic regression modeled odds of any breastfeeding versus formula feeding only. Multinomial logistic regression modeled a three-category breastfeeding outcome—exclusive breastfeeding, mixed breastfeeding/formula, or formula only (reference group). All regression analyses were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, median neighborhood income, living situation, prenatal depression, parity, mode of birth, and preterm birth. These models included the “missing” option, which allowed us to keep women in the model with missing data on categorical covariates (median neighborhood household income [n = 3], living situation [n = 19], mode of birth [n = 3], gestational age [n = 20]). Very few women who did not breastfeed 2 weeks postpartum reported breastfeeding 2 months postpartum (n = 3), and analyses of continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum were limited to the subset of women who self-reported breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum. We also performed Cochran–Armitage tests to examine the linear trend between ACE score and our two main breastfeeding outcomes: any breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum and continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4.

Results

Our study population (N = 926) was 42.4% non-Hispanic White, 22.8% Hispanic, 10.9% Black, 19.3% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 4.5% other/unknown race/ethnicity; 13.5% were aged 18–24 years, 68.6% were aged 25–34 years, and 17.9% were aged 35+ years. Two weeks postpartum, 92.2% of women reported any breastfeeding, 62.9% reported exclusive breastfeeding, and 29.4% reported mixed breastfeeding/formula. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of women by breastfeeding status at 2 weeks are shown in Table 1. White, Asian, and other/unknown race/ethnicity, higher neighborhood household income, being primiparious, and having a greater number of ACEs were associated with higher prevalence of breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum.

Table 1.

Unadjusted Prevalence of Sociodemographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Adverse Childhood Experiences by Early Breastfeeding Status 2 Weeks Postpartum (N = 926)

| Characteristic | Overall, N (%) | Any breastfeeding, N = 854 (92.2%), N (%) | pa | Exclusive breastfeeding, N = 582 (62.9%), N (%) | Mixed breastfeeding/formula, N = 272 (29.4%), N (%) | Formula only, N = 72 (7.8%), N (%) | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||||||

| 18–25 | 125 (13.5) | 109 (87.2) | 0.07 | 75 (60.0) | 34 (27.2) | 16 (12.8) | 0.07 |

| 26–35 | 635 (68.6) | 589 (92.8) | 410 (64.6) | 179 (28.2) | 46 (7.2) | ||

| 36+ | 166 (17.9) | 156 (94.0) | 97 (58.4) | 59 (35.5) | 10 (6.0) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 393 (42.4) | 367 (93.4) | <0.01 | 282 (71.8) | 85 (21.6) | 26 (6.6) | <0.01 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 179 (19.3) | 174 (97.2) | 105 (58.7) | 69 (38.6) | 5 (2.8) | ||

| Black | 101 (10.9) | 86 (85.2) | 54 (53.5) | 32 (31.7) | 15 (14.9) | ||

| Hispanic | 211 (22.8) | 187 (88.6) | 115 (54.5) | 72 (34.1) | 24 (11.4) | ||

| Other/unknown | 42 (4.5) | 40 (95.2) | 26 (61.9) | 14 (33.3) | 2 (4.8) | ||

| Neighborhood median household income | |||||||

| <$97,000 | 432 (46.8) | 381 (88.2) | <0.01 | 269 (62.3) | 112 (25.9) | 51 (11.8) | <0.01 |

| >$97,000 | 491 (53.2) | 470 (95.7) | 311 (63.3) | 159 (32.4) | 21 (4.3) | ||

| Lives with partner/baby's father | |||||||

| Yes | 838 (92.4) | 774 (92.4) | 0.46 | 529 (63.1) | 245 (29.2) | 64 (7.6) | 0.75 |

| No | 69 (7.6) | 62 (89.9) | 43 (62.3) | 19 (27.5) | 7 (10.1) | ||

| Prenatal depression symptoms | |||||||

| None | 734 (79.3) | 674 (91.8) | 0.38 | 471 (64.2) | 203 (27.7) | 60 (8.2) | 0.07 |

| Any | 192 (20.7) | 180 (93.8) | 111 (57.8) | 69 (35.9) | 12 (6.3) | ||

| Parity | |||||||

| 1 | 362 (39.1) | 345 (95.3) | <0.01 | 226 (62.4) | 119 (32.9) | 17 (4.7) | <0.01 |

| 2+ | 564 (60.9) | 509 (90.3) | 356 (63.1) | 153 (27.1) | 55 (9.8) | ||

| Mode of birth | |||||||

| Cesarean section | 225 (24.4) | 206 (91.6) | 0.68 | 126 (56.0) | 80 (35.6) | 19 (8.4) | 0.04 |

| Vaginal | 698 (75.6) | 645 (92.4) | 454 (65.0) | 191 (27.4) | 53 (7.6) | ||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks)c | |||||||

| Yes | 37 (4.1) | 35 (94.6) | 0.76 | 17 (46.0) | 18 (48.7) | 2 (5.4) | 0.04 |

| No | 869 (95.9) | 800 (92.1) | 549 (63.2) | 251 (28.9) | 69 (7.9) | ||

| ACEs | |||||||

| Loss of parent | 208 (22.5) | 195 (93.8) | 0.35 | 133 (63.9) | 62 (29.8) | 13 (6.3) | 0.65 |

| Emotional abuse | 144 (15.6) | 137 (95.1) | 0.16 | 98 (68.1) | 39 (27.1) | 7 (4.9) | 0.23 |

| Physical abuse | 60 (6.5) | 57 (95.0) | 0.41c | 38 (63.3) | 19 (31.7) | 3 (5.0) | 0.69 |

| Sexual abuse | 70 (7.6) | 67 (95.7) | 0.26 | 54 (77.1) | 13 (18.6) | 3 (4.3) | 0.04 |

| Lived with someone | |||||||

| With a substance use problem | 136 (14.7) | 129 (94.9) | 0.22 | 96 (70.6) | 33 (24.3) | 7 (9.7) | 0.11 |

| Who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide | 133 (14.4) | 127 (95.5) | 0.13 | 94 (70.7) | 33 (24.8) | 6 (4.5) | 0.09 |

| Who went to jail or prison | 73 (7.9) | 68 (93.2) | 0.76 | 46 (63.0) | 22 (30.1) | 5 (6.9) | 0.95 |

| Who hit, punched, beat, or threatened to harm another adult in home | 72 (7.8) | 68 (94.4) | 0.46 | 45 (62.5) | 23 (31.9) | 4 (5.6) | 0.71 |

| No. of ACEs | |||||||

| 0 | 539 (58.2) | 487 (90.4) | 0.04 | 323 (59.9) | 164 (30.4) | 52 (9.7) | 0.04 |

| 1 | 178 (19.2) | 168 (94.4) | 113 (63.5) | 55 (30.9) | 10 (5.6) | ||

| 2+ | 209 (22.6) | 199 (94.2) | 146 (69.9) | 53 (25.4) | 10 (4.8) | ||

All p-values calculated using chi-square test unless indicated otherwise. Percentages in Overall column reflect column percentages, while all other percentages reflect row percentages.

Comparison between any breastfeeding and formula only.

Comparison between exclusive breastfeeding, mixed breastfeeding/formula, and formula only.

p-Value calculated using Fisher's exact test.

ACEs, adverse childhood experiences.

Among those breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum, 86.4% reported any breastfeeding 2 months postpartrum (57.5% exclusive and 28.9% mixed breastfeeding/formula). White and Asian race/ethnicity, living with partner/baby's father, being multiparous, and having a vaginal birth were associated with higher prevalence of continued breastfeeding at 2 months, whereas younger age (18–25 years) was associated with a lower prevalence of continued breastfeeding at 2 months (Table 2). Furthermore, childhood loss of parent, living with someone during childhood who went to jail or prison, or with someone who hit, punched, beat, or threatened to harm another adult in home were associated with lower prevalence of continued breastfeeding.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Prevalence of Sociodemographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Adverse Childhood Experiences by Continued Breastfeeding Status 2 Months Postpartum, Among Those Who Breastfed at 2 Weeks (N = 854)

| Characteristic | Overall, N (%) | Any breastfeeding, N = 735 (86.4%), N (%) | pa | Exclusive breastfeeding, N = 491 (57.5%), N (%) | Mixed breastfeeding/Formula, N = 247 (28.9%), N (%) | Formula only, N = 116 (13.6%), N (%) | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||||||

| 18–25 | 109 (12.8) | 82 (75.2) | <0.01 | 56 (51.4) | 26 (23.9) | 27 (24.8) | <0.01 |

| 26–35 | 589 (69.0) | 524 (89.0) | 355 (60.3) | 169 (28.7) | 65 (11.0) | ||

| 36+ | 156 (18.3) | 132 (84.6) | 80 (51.3) | 52 (33.3) | 24 (15.4) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 367 (43.0) | 324 (88.3) | <0.01 | 242 (65.9) | 82 (22.3) | 43 (11.7) | <0.01 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 174 (20.4) | 164 (94.3) | 99 (56.9) | 65 (37.4) | 10 (5.8) | ||

| Black | 86 (10.1) | 63 (73.3) | 34 (39.5) | 29 (33.7) | 23 (26.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 187 (21.9) | 153 (81.8) | 95 (50.8) | 58 (31.0) | 34 (18.2) | ||

| Other/unknown | 40 (4.7) | 34 (85.0) | 21 (52.5) | 13 (32.5) | 6 (15.0) | ||

| Neighborhood median household income | |||||||

| <$97,000 | 381 (44.8) | 324 (85.0) | 0.31 | 222 (58.3) | 102 (26.8) | 57 (15.0) | 0.33 |

| >$97,000 | 470 (55.2) | 411 (87.5) | 266 (56.6) | 145 (30.9) | 59 (12.6) | ||

| Lives with partner/baby's father | |||||||

| Yes | 774 (92.6) | 678 (87.6) | <0.01 | 460 (59.4) | 218 (28.2) | 96 (12.4) | <0.01 |

| No | 62 (7.4) | 47 (75.8) | 23 (37.1) | 24 (38.7) | 15 (24.2) | ||

| Prenatal depression symptoms | |||||||

| None | 674 (78.9) | 585 (86.8) | 0.53 | 396 (58.8) | 189 (28.0) | 89 (13.2) | 0.35 |

| Any | 180 (21.1) | 153 (85.0) | 95 (52.8) | 58 (32.3) | 27 (15.0) | ||

| Parity | |||||||

| 1 | 345 (40.4) | 284 (82.3) | <0.01 | 179 (51.9) | 105 (30.4) | 61 (17.7) | <0.01 |

| 2+ | 509 (59.6) | 454 (89.2) | 312 (61.3) | 142 (27.9) | 55 (10.8) | ||

| Mode of birth | |||||||

| Cesarean section | 206 (24.2) | 164 (79.6) | <0.01 | 95 (46.1) | 69 (33.5) | 42 (20.4) | <0.01 |

| Vaginal | 645 (75.8) | 571 (88.5) | 394 (61.1) | 177 (27.4) | 74 (11.5) | ||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks)c | |||||||

| Yes | 35 (4.2) | 29 (82.9) | 0.61 | 12 (34.3) | 17 (48.6) | 6 (17.1) | 0.01 |

| No | 800 (95.8) | 691 (86.4) | 464 (58.0) | 227 (28.4) | 109 (13.6) | ||

| ACEs | |||||||

| Loss of parent | 195 (22.8) | 159 (81.6) | 0.02 | 106 (54.4) | 53 (27.2) | 36 (18.5) | 0.08 |

| Emotional abuse | 137 (16.0) | 116 (84.7) | 0.51 | 79 (57.7) | 37 (27.0) | 21 (15.3) | 0.75 |

| Physical abuse | 57 (6.7) | 49 (86.0) | 0.92 | 35 (61.4) | 14 (24.6) | 8 (14.0) | 0.75 |

| Sexual abuse | 67 (7.9) | 59 (88.1) | 0.68 | 40 (59.7) | 19 (28.4) | 8 (11.9) | 0.90 |

| Lived with someone | |||||||

| With a substance use problem | 129 (15.1) | 108 (83.7) | 0.33 | 76 (58.9) | 32 (24.8) | 21 (16.3) | 0.42 |

| Who was depressed, mentally ill or attempted suicide | 127 (14.9) | 107 (84.3) | 0.44 | 75 (59.1) | 32 (25.2) | 20 (15.8) | 0.52 |

| Who went to jail or prison | 68 (8.0) | 51 (75.0) | <0.01 | 37 (54.4) | 14 (20.6) | 17 (25.0) | 0.01 |

| Who hit, punched, beat, or threatened to harm another adult in home | 68 (8.0) | 53 (77.9) | 0.03 | 33 (48.5) | 20 (29.4) | 15 (22.1) | 0.08 |

| No. of ACEs | |||||||

| 0 | 487 (57.0) | 429 (88.1) | 0.19 | 281 (57.7) | 148 (30.4) | 58 (11.9) | 0.33 |

| 1 | 168 (19.7) | 144 (85.7) | 94 (56.0) | 50 (29.8) | 24 (14.3) | ||

| 2+ | 199 (23.3) | 165 (82.9) | 116 (58.3) | 49 (24.6) | 34 (17.1) | ||

All p-values calculated using chi-square test unless indicated otherwise. Percentages in Overall column reflect column percentages, while all other percentages reflect row percentages.

Comparison between any breastfeeding and formula only.

Comparison between exclusive breastfeeding, mixed breastfeeding/formula, and formula only.

p-Value calculated using Fisher's exact test.

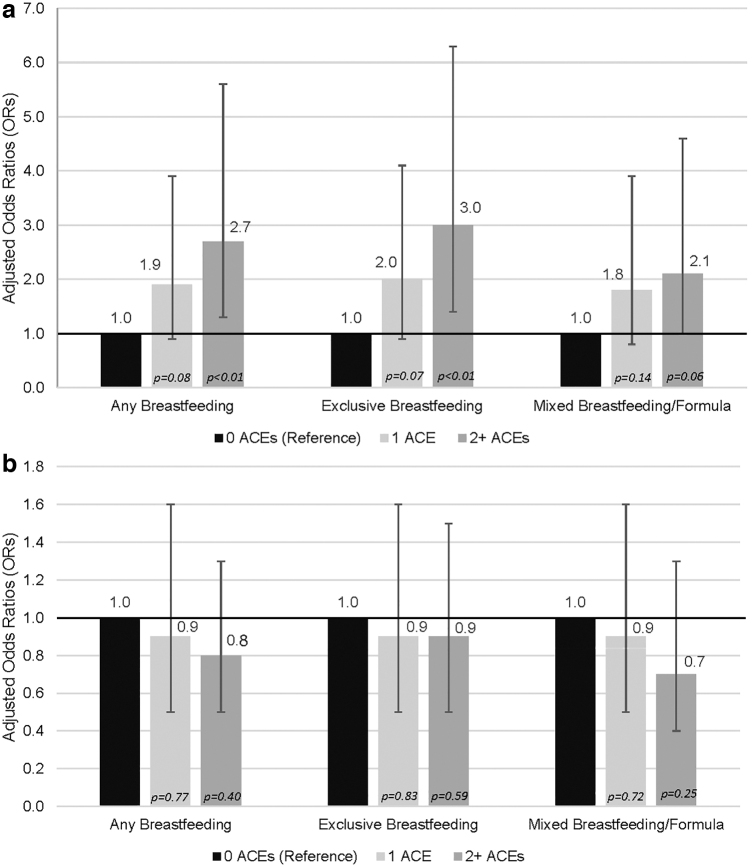

In multivariable models that adjusted for sociodemographic factors, having a greater number of ACEs was associated with significantly greater odds of early breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum (Fig. 1a). Compared with women with 0 ACEs, women who had 1 ACE did not have significantly increased odds of any breastfeeding (odds ratio [OR] = 1.9; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.9–3.9), exclusive breastfeeding (OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 0.9–4.1), or mixed breastfeeding/formula (OR = 1.8, 95% CI: 0.8–3.9). However, compared with women with 0 ACEs, women with 2+ ACEs had significantly increased odds of any breastfeeding (OR = 2.7, 95% CI = 1.3, 5.6) and exclusive breastfeeding (OR = 3.0, 95% CI: 1.4–6.3), but not mixed breastfeeding/formula (OR = 2.1, 95% CI: 1.0–4.6). Black race/ethnicity (compared with non-Hispanic White; OR = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.2–0.9) and being multiparous (compared with primiparous; OR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7) were associated with significantly lower odds of any breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum, whereas having a neighborhood household income above the median (OR = 2.7, 95% CI: 1.6–4.7) was associated with significantly higher odds of any breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum (Table 3). Individual ACEs were not significantly associated with breastfeeding outcomes 2 weeks postpartum. The Cochran–Armitage test for trend was statistically significant for breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum (p = 0.02), indicating that the percentage of women breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum increases as ACE count increases.

FIG. 1.

(a) Odds of early breastfeeding versus formula only 2 weeks postpartum by ACEs (N = 926). (b) Odds of continued breastfeeding versus formula only, 2 months postpartum, by ACEs, among early breastfeeders (N = 854). ACEs, adverse childhood experiences.

Table 3.

Multivariable Models of Early Breastfeeding Versus Formula Only 2 Weeks Postpartum

| Any early breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | Exclusive early breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | Mixed early breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18–25 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 26–35 | 1.9 (1.0–3.7) | 0.07 | 1.9 (0.9–3.7) | 0.07 | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) | 0.09 |

| 36+ | 2.3 (0.9–5.6) | 0.08 | 2.0 (0.8–5.2) | 0.13 | 2.8 (1.0–7.6) | 0.04 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.4 (0.9–6.5) | 0.08 | 2.0 (0.7–5.4) | 0.17 | 3.8 (1.4–10.7) | 0.01 |

| Black | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 0.04 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | 0.01 | 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | 0.57 |

| Hispanic | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.17 | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) | 0.04 | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 0.71 |

| Other/unknown | 1.6 (0.3–7.2) | 0.55 | 1.4 (0.3–6.4) | 0.68 | 2.3 (0.5–11.0) | 0.32 |

| Neighborhood median household income | ||||||

| <$97,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| >$97,000 | 2.7 (1.6–4.7) | <0.01 | 2.5 (1.4–4.4) | <0.01 | 3.2 (1.8–5.7) | <0.01 |

| Lives with partner/baby's father | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| No | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 0.80 | 1.0 (0.4–2.5) | 0.95 | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 0.57 |

| Prenatal depression symptoms | ||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Any | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | 0.76 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 0.99 | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 0.36 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2+ | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | <0.01 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | <0.01 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | <0.01 |

| Mode of birth | ||||||

| Vaginal | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Cesarean section | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | 0.49 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.32 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 0.99 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.8 (0.4–8.2) | 0.45 | 1.3 (0.3–6.2) | 0.72 | 2.6 (0.6–12.2) | 0.22 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| No. of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1 | 1.9 (0.9–3.9) | 0.08 | 2.0 (0.9–4.1) | 0.07 | 1.8 (0.8–3.9) | 0.14 |

| 2+ | 2.7 (1.3–5.6) | <0.01 | 3.0 (1.4–6.3) | <0.01 | 2.1 (1.0–4.6) | 0.06 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Among those who initially breastfed at 2 weeks, the number of ACEs was not significantly associated with continued breastfeeding outcomes 2 months postpartum (Fig. 1b). Black race/ethnicity (compared with non-Hispanic White; OR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7) and cesarean delivery (compared with vaginal; OR = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.8) were associated with significantly lower odds of any continued breastfeeding at 2 months. Asian race/ethnicity (compared with non-Hispanic White; OR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.1–4.7), older age (age 26–35 vs. <25 years; OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.1–3.3), and being primiparous (compared with multiparous; OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.1–2.7) were associated with significantly higher odds of any continued breastfeeding at 2 months (Table 4). The Cochran–Armitage test for trend was not statistically significant for continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum (p = 1.0), indicating that the percentage of women with continued breastfeeding 2 months postpartum does not increase as ACE count increases.

Table 4.

Multivariable Models of Continued Breastfeeding Versus Formula Only 2 Months Postpartum Among Those Who Breastfed at Two Weeks

| Any continuedbreastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | Exclusive continued breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | Mixed continued breastfeeding, OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||||

| 18–25 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 26–35 | 1.9 (1.1–3.3) | 0.03 | 1.7 (0.9–3.1) | 0.08 | 2.3 (1.2–4.4) | 0.02 |

| 36+ | 1.1 (0.5–2.2) | 0.81 | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.74 | 1.6 (0.7–3.7) | 0.26 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.3 (1.1–4.7) | 0.03 | 1.9 (0.9–4.0) | 0.09 | 3.2 (1.5–7.0) | <0.01 |

| Black | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | <0.01 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | <0.01 | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | 0.29 |

| Hispanic | 0.6 (0.4–1.1) | 0.08 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.02 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.80 |

| Other/unknown | 0.9 (0.3–2.3) | 0.77 | 0.7 (0.3–2.0) | 0.52 | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | 0.72 |

| Neighborhood median household income | ||||||

| <$97,000 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| >$97,000 | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) | 0.89 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.64 | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.67 |

| Lives with partner/baby's father | ||||||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| No | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.63 | 0.6 (0.3–1.4) | 0.25 | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | 0.64 |

| Prenatal depression symptoms | ||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Any | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.98 | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 0.82 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 0.76 |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2+ | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 0.01 | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | <0.01 | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 0.16 |

| Mode of birth | ||||||

| Vaginal | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Cesarean section | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | <0.01 | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | <0.01 | 0.6 (0.4–1.0) | 0.04 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 0.82 | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) | 0.47 | 1.9 (0.7–5.2) | 0.24 |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| No. of ACEs | ||||||

| 0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.77 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.83 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.72 |

| 2+ | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.40 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.59 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.25 |

Individual ACEs were not significantly associated with continued breastfeeding outcomes 2 months postpartum, with the exception that women who, as a child, lived with someone who went to jail or prison had significantly lower odds of any continued breastfeeding (OR = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9) and mixed breastfeeding/formula (OR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.9) relative to formula only.

Discussion

ACEs have recently been recognized for their potential influence on breastfeeding behaviors, but prior studies have primarily focused on childhood sexual abuse, and results have been mixed.23,25–28,30–32 Results from this large study of pregnant women universally screened for ACEs during standard prenatal care indicated that women with two or more ACEs had elevated odds of early breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum compared with those without ACEs, but these early gains were not sustained 2 months postpartum. The association between ACEs and early breastfeeding appeared to be graded; although the associations for 1 ACE were not statistically significant, the trend test indicated that the percentage of women breastfeeding 2 weeks postpartum increases significantly as ACE count increases. These findings support prior work indicating that women exposed to childhood adversity may make more of an effort to breastfeed and develop strong attachment with their child initially.25 However, there are a number of other possible explanations. For example, women with ACEs may attempt to correct or compensate for their personal past traumas by doing what is best for their baby, and they may be more concerned about parenting practices than those without ACEs.25 Additional research is needed to better understand the mechanisms that contribute to increased rates of early breastfeeding among women with ACEs, to inform efforts to help them overcome breastfeeding challenges and maintain their early breastfeeding success.

While all pregnant women were provided with a list of KPNC and external resources (e.g., support groups, parenting classes, health education) as part of the ACEs screening, those who screened positive for ACEs were also educated about the impact of ACEs on health and referred to behavioral health or psychiatry, as needed. Thus, it is also possible that the ACEs screening and discussion during prenatal care, while not focused specifically on breastfeeding, may have led to greater appreciation among women of the impact of ACEs on perinatal health, contributing to increased attachement and initial motivation to succeed with early breastfeeding among women with ACEs. Future studies are needed to understand whether patient–provider discussions about the health impacts of ACEs during prenatal care might lead to enhanced breastfeeding motivation and to evaluate how that motivation can be sustained over time.

It is noteworthy that ACE type was not significantly associated with breastfeeding outcomes at either time point, with the exception that women who had lived with someone who went to jail or prison had significantly lower odds of any continued breastfeeding. Future quantitative and qualitative research is needed to examine whether this finding is robust and replicable and to better understand the mechanisms that may contribute to lower rates of continued breastfeeding among women who (as children) lived with someone who went to jail or prison. The lack of significant associations with other ACEs may be due to the small number of women who were only using formula 2 weeks and 2 months postpartum when broken down by individual ACEs. In addition, there was a notable pattern of lower odds of continued breastfeeding associated with a greater number of ACEs, consistent with several prior studies26–28; however, these results were not significant in our sample. Additional research with larger samples is needed to better understand how ACEs and specific types of childhood trauma contribute to early and continued breastfeeding behaviors.

Health care organizations are uniquely positioned to empower women to overcome barriers to breastfeeding. Results indicate that ACEs are not associated with lower rates of breastfeeding and in fact suggest that ACEs are related to greater early success with breastfeeding. The initiation and continuation of breastfeeding is complex, and future qualitative studies that examine reasons for greater initial breastfeeding success among women with ACEs are needed to better understand how we can support these mothers to meet their breastfeeding goals. Conversely, consistent with prior research,1 our study found lower rates of any early breastfeeding among non-Hispanic Black women and those with lower neighborhood household incomes. Appropriate and targeted interventions in the early postpartum period (e.g., outreach by health educators, psychologists or other mental health providers, parental education, family support, and proactive telephone calls with lactation experts), for all women, and especially those who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health, hold promise to support sustained breastfeeding to reduce health disparities and improve maternal and pediatric outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine the association between number and type of ACE and both early and continued breastfeeding among a large sample of women screened for ACEs as part of standard prenatal care. KPNCs integrated health care delivery system allowed us to link data from women's EHRs to pediatric records of their child to examine these important questions in a diverse and representative sample of pregnant women after adjusting for a range of covariates. Our study also had several limitations. The study took place in three KPNC medical centers and was limited to English-speaking adult women screened for ACEs at their second or third prenatal visit and results may not generalize to non-English speaking, adolescent, or uninsured populations. However, early and continued breastfeeding rates and differences in breastfeeding by race/ethnicity, income, and age were consistent with prior studies.1,4,39 In addition, women who chose not to complete the questionnaire (5%) and those without a 2-week and 2-month pediatric appointment (17%) were excluded, which may have impacted findings. Data on ACEs and breastfeeding outcomes were based on self-report and are subjected to self-report biases; however, ACEs were assessed confidentially in a private examination room, and prior research shows good test–retest reliability for ACEs.40 Furthermore, women were asked about their current breastfeeding behaviors postpartum, limiting the likelihood of recall bias.

To maximize our sample size by combining data from two pilot studies, the current study was limited to an 8- versus 10-item ACEs screening questionnaire, as two questions about neglect were only available for a subset of women. In addition, our screening questionnaire did not measure ACE severity, duration, or age at exposure. The sample size of women with certain individual types of ACEs was sometimes small when broken down by breastfeeding outcome, limiting statistical power to detect differences in breastfeeding outcomes by ACE type. Furthermore, few women had 3+ (14%) or 4+ (8%) ACEs, and we categorized ACEs into 0, 1, and 2+ to ensure adequate sample sizes in analyses of ACEs and breastfeeding outcomes. Future studies with larger samples and more detailed assessment of ACE exposure (including childhood exposure to neglect), alternative categorization of ACEs (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3, 4+), and investigation of whether ACE score is moderated by other factors (e.g., sociodemographics, prenatal depression) will be important for improving our understanding of the role of exposure to early adversity and maternal breastfeeding behaviors.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Information

This study was supported by two grants from the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefits Program and the National Institute on Drug Abuse K01 Award (DA043604).

References

- 1. Eidelman AI. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk: An analysis of the American Academy of Pediatrics 2012 Breastfeeding Policy Statement. Breastfeed Med 2012;7:323–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding infographics. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/infographics/en Accessed July1, 2020

- 3. Odom EC, Li R, Scanlon KS, Perrine CG, Grummer-Strawn L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2013;131:e726–e732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Results: Breastfeeding rates. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/results.html Accessed July1, 2020

- 5. Sriraman NK, Kellams A. Breastfeeding: What are the barriers? Why women struggle to achieve their goals. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25:714–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perrine CG, Galuska DA, Dohack JL, et al. . Vital signs: Improvements in maternity care policies and practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1112–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McAndrew F, Thompson J, Fellows L, Large A, Speed M, Renfrew MJ. Infant Feeding Survey 2010. Health and Social Care Information Centre 2012. Available at: https://sp.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/7281/mrdoc/pdf/7281_ifs-uk-2010_report.pdf Accessed July1, 2020

- 8. Borra C, Iacovou M, Sevilla A. New evidence on breastfeeding and postpartum depression: The importance of understanding women's intentions. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dias CC, Figueiredo B. Breastfeeding and depression: A systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2015;171:142–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamdan A, Tamim H. The relationship between postpartum depression and breastfeeding. Int J Psychiatry Med 2012;43:243–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Islam MJ, Baird K, Mazerolle P, Broidy L. Exploring the influence of psychosocial factors on exclusive breastfeeding in Bangladesh. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:173–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wallenborn JT, Cha S, Masho SW. Association between intimate partner violence and breastfeeding duration: Results from the 2004–2014 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. J Hum Lact 2018;34:233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller-Graff LE, Ahmed AH, Paulson JL. Intimate partner violence and breastfeeding outcomes in a sample of low-income women. J Hum Lact 2018;34:494–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults—Five states, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59:1609–1613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leeners B, Richter-Appelt H, Imthurn B, Rath W. Influence of childhood sexual abuse on pregnancy, delivery, and the early postpartum period in adult women. J Psychosom Res 2006;61:139–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leeners B, Rath W, Block E, Gorres G, Tschudin S. Risk factors for unfavorable pregnancy outcome in women with adverse childhood experiences. J Perinat Med 2014;42:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seng JS, Sperlich M, Low LK. Mental health, demographic, and risk behavior profiles of pregnant survivors of childhood and adult abuse. J Midwifery Womens Health 2008;53:511–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grimstad H, Schei B. Pregnancy and delivery for women with a history of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1999;23:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McDonnell CG, Valentino K. Intergenerational effects of childhood trauma: Evaluating pathways among maternal ACEs, perinatal depressive symptoms, and infant outcomes. Child Maltreatment 2016;21:317–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berthelot N, Ensink K, Bernazzani O, Normandin L, Luyten P, Fonagy P. Intergenerational transmission of attachment in abused and neglected mothers: The role of trauma-specific reflective functioning. Infant Ment Health J 2015;36:200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elfgen C, Hagenbuch N, Gorres G, Block E, Leeners B. Breastfeeding in women having experienced childhood sexual abuse. J Hum Lact 2017;33:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kendall-Tackett K. Breastfeeding and the sexual abuse survivor. J Hum Lact 1998;14:125–130; quiz 131–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kendall-Tackett K, Cong Z, Hale TW. Depression, sleep quality, and maternal well-being in postpartum women with a history of sexual assault: A comparison of breastfeeding, mixed-feeding, and formula-feeding mothers. Breastfeed Med 2013;8:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coles J. Qualitative study of breastfeeding after childhood sexual assault. J Hum Lact 2009;25:317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prentice JC, Lu MC, Lange L, Halfon N. The association between reported childhood sexual abuse and breastfeeding initiation. J Hum Lact 2002;18:219–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ukah UV, Adu PA, De Silva DA, von Dadelszen P. The impact of a history of Adverse Childhood Experiences on breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity: Findings from a National Population Health Survey. Breastfeed Med 2016;11:544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sorbo MF, Lukasse M, Brantsaeter AL, Grimstad H. Past and recent abuse is associated with early cessation of breast feeding: Results from a large prospective cohort in Norway. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Watkins S, Meltzer-Brody S, Zolnoun D, Stuebe A. Early breastfeeding experiences and postpartum depression. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:214–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Islam MJ, Mazerolle P, Broidy L, Baird K. Does the type of maltreatment matter? Assessing the individual and combined effects of multiple forms of childhood maltreatment on exclusive breastfeeding behavior. Child Abuse Negl 2018;86:290–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Coles J, Anderson A, Loxton D. Breastfeeding duration after childhood sexual abuse: An Australian cohort study. J Hum Lact 2016;32:NP28–NP35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bowman KG, Ryberg JW, Becker H. Examining the relationship between a childhood history of sexual abuse and later dissociation, breast-feeding practices, and parenting anxiety. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:1304–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bullock LF, Libbus MK, Sable MR. Battering and breastfeeding in a WIC population. Can J Nurs Res 2001;32:43–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selby JV, Smith DH, Johnson ES, Raebel MA, Friedman GD, McFarland BH. Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. In: Strom BL, ed. Pharmacoepidemiology. New York: Wiley, 2005:241–259 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terhune C. Report: Kaiser tops state health insurance market with 40% share. Los Angeles Times, 2013. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2013/jan/29/business/la-fi-mo-health-insure-market-20130129 Accessed July1, 2020

- 35. Flanagan T, Alabaster A, McCaw B, Stoller N, Watson C, Young-Wolff KC. Feasibility and acceptability of screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in prenatal care. J Women's Health 2018;27:903–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey ACE data, 2009–2014. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/ace_brfss.html Accessed July1, 2020

- 37. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Young-Wolff KC, Alabaster A, McCaw B, et al. . Adverse childhood experiences and mental and behavioral health conditions during pregnancy: The role of resilience. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:452–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Heck KE, Braveman P, Cubbin C, Chavez GF, Kiely JL. Socioeconomic status and breastfeeding initiation among California mothers. Public Health Rep 2006;121:51–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences study. Pediatrics 2003;111:564–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]