Abstract

Objectives

To compare the clinical outcomes of anterior controllable antedisplacement fusion (ACAF), a new surgical technique, with laminoplasty for the treatment of multilevel severe cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) based on a 2‐year follow‐up.

Methods

Clinical data of 53 patients (21 by ACAF and 32 by laminoplasty) who have accepted surgery for treatment of cervical myelopathy caused by multilevel severe OPLL (occupying rate ≥ 50%) from March 2015 to March 2017 were retrospectively reviewed and compared between ACAF group and laminoplasty group. Operative time, blood loss, and complications of the two groups were recorded. Radiographic parameters were evaluated pre‐ and postoperatively: cervical lordosis on X‐ray, space available for the cord (SAC) and the occupying ratio (OR) on computed tomography (CT), and the anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the spinal cord at the narrowest level and the spinal cord curvature on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scoring was used to evaluate neurologic recovery. Statistical analysis was conducted to analyze the differences between two groups. The Mann–Whitney U test and chi square test were used to compare categorical variables. unpaired t test was used to compare continuous data.

Results

All patients were followed up for at least 24 months. The operative time was longer in ACAF group (286.5 vs 178.2 min, P < 0.05). The blood loss showed no significant difference (291.6 vs 318.3 mL, P > 0.05). Less complications were observed in ACAF group than in laminoplasty group (one case [4.7%] of C5 palsy and one case [4.7%] of cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] leakage in ACAF group; four cases [12.5%] of C5 palsy, two cases [6.3%] of CSF leakage, and four cases [12.5%] of axial symptoms in laminoplasty group). The mean JOA score at last follow‐up (14.6 vs 12.8, P < 0.05) and the improvement rate (IR) (63.8% vs 47.8%, P < 0.05) in ACAF group were superior to those in laminoplasty group significantly. The postoperative OR (16.7% vs 40.9%, P < 0.05), SAC (150.8 vs 110.5 mm2, P < 0.05), AP spinal cord diameter (5.5 vs 4.2 mm, P < 0.05), and cervical lordosis (12.7° vs 4.7°, P < 0.05) were improved more considerably in ACAF group, with significant differences between two groups. Notably, the spinal cord on MRI showed a better curvature in ACAF group.

Conclusions

This study showed that ACAF is considered superior to laminoplasty for the treatment of multilevel severe OPLL as anterior direct decompression and better curvature of the spinal cord led to satisfactory neurologic outcomes and low complication rate.

Keywords: Anterior controllable antedisplacement and fusion (ACAF), Complication, Laminoplasty, Myelopathy, Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL)

The study aimed to compare the clinical outcomes of anterior controllable antedisplacement fusion (ACAF), a new surgical technique, with laminoplasty for the treatment of multilevel severe cervical OPLL based on a 2‐year follow‐up. By achieving anterior direct decompression and better curvature of the spinal cord, satisfactory neurologic outcomes, and low complication rate. ACAF is considered superior to laminoplasty for the treatment of multilevel severe OPLL.

Introduction

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) is a hyperostotic condition that results in ectopic calcification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and commonly occurs in the Asian population 1 , 2 . Patients with OPLL usually develop into various degrees of neurological symptoms, and surgical treatment is recommended for those with severe neurological dysfunction and intolerable symptoms. The primary surgical strategies include anterior and posterior approaches; however, some controversies still remain about the optimal surgical method, especially when dealing with multilevel severe OPLL.

Anterior approach surgery mainly refers to anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) or anterior decompression and fusion (ADF) with floating method, which can directly decompress the spinal cord and achieve satisfied outcomes. However, this procedure is technically demanding and associated with many complications such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, hardware failure and neural injury. Especially, when it comes to multilevel or severe OPLL, anterior procedure becomes riskier, and the use of long titanium mesh can significantly increase the risk of internal fixation failure. In this situation, the posterior procedure becomes an alternative. 3 , 4 Laminoplasty, one of the widely used posterior procedure, has been reported effective and safe when dealing with multilevel OPLL. However, the clinical outcomes of laminoplasty are not satisfactory for cases with K‐line negative or occupying ratio (OR) more than 60% 5 . For severe multilevel OPLL, the posterior approach has the problems of insufficient decompression and limited neural functional recovery, and the anterior approach also confronts the risky operation during decompression and the difficulties of cervical reconstruction. Therefore, sometimes it is necessary to resort to the complex, traumatic, and expensive anterior–posterior procedure. Driven by the increasing demand for curative effect, the operation method is constantly developing and innovating.

Previously, we reported a novel technique named anterior controllable antedisplacement and fusion (ACAF) surgery that can achieve anterior direct decompression without resecting ossification. By inheriting the advantages of classical anterior approach and under the support of the developing internal fixation techniques and surgical instruments, ACAF has been reported effective for multilevel severe OPLL 6 . Theoretically, the decompression process of ACAF does not involve the operation of surgical instruments inside the spinal canal, which avoids the mechanical pressure on spinal cord caused by the space‐occupying effect of surgical instruments, so as to achieve a safe decompression. The purpose of this study was: (i) to further evaluate and compare the clinical outcomes and complications of ACAF and laminoplasty for the treatment of severe multilevel OPLL based on a 2‐year follow‐up; (ii) to discuss the technical details of ACAF about how to avoid CSF leakage and C5 palsy; and (iii) to provide references for operational option for the treatment of severe multilevel OPLL.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion

Inclusion criteria: (i) diagnosed with OPLL by X‐ray and computed tomography (CT) and accepted surgery of ACAF or laminoplasty; (ii) ossified mass extended three or more levels; and (iii) ossified mass occupied more than 50% diameter of the spinal canal. Exclusion criteria: (i) patients with myelopathy caused by other diseases such as disc herniation or ossification of the ligamentum flavum; (ii) history of injury; (iii) history of previous cervical spine surgery; and (iv) patients with cervical kyphosis.

Clinical data of 53 patients treated for cervical myelopathy caused by multilevel severe OPLL from March 2015 to March 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. Among them, 21 patients (13 males, eight females; mean age 60.7 ± 7.2 years [range, 45–78 years]) underwent ACAF surgery. Laminoplasty was performed on 32 patients (17 males, 15 females; mean age 57.6 ± 6.3 years [range, 42–73 years]). The best indications of ACAF and laminoplasty still require more argumentations. After surgical details, expected benefits, potential risks and complications of ACAF and laminoplasty were clearly explained to each patient, the operational method was determined based on experience of surgeons and wishes of patients. The patients' physical condition, condition of cervical stability, and severity of disc herniation are all taken into consideration. Considering the seemingly adverse effects of poor cervical curvature on posterior surgery, patients with preoperative cervical kyphosis were excluded from this study. In practical work, for OPLL patients with cervical kyphosis, we used ACAF technology for treatment. The ethical review board of Shanghai Second Military Medical University granted approval to conduct our study. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines of the ethical review board of our institution. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Operative Procedures

In the ACAF group, procedures were performed as described by Sun et al. 6 (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram for ACAF surgery. (A) the ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament at C4–C6; (B) resection of C3/4, C4/5, C5/6, and C6/7 intervertebral discs and remove the anterior bone of C4–C6 vertebrae; (C) grooving at the operator's opposite side, partially grooving at the operator's side; (D) installing cages, screws, and titanium plate and complete grooving at the operator's side; (E) sagittal view after installing internal fixation; (F) hoisting C4–C6 vertebrae.

Fig. 2.

ACAF surgery. (A, G) Preoperative CT and MRI sagittal scan demonstrated spinal stenosis from C3 to C5, and severe OPLL from C4 to C5. The red dash line square showed the vertebral‐OPLL complex (VOC) levels. (B) The red dash line square showed the cut part of the anterior bone with the thickness according to ossified ligament. (C) Postoperative CT coronal reconstruction demonstrated the bilateral osteotomies conducted at the inner border of uncovertebral joints. (D) The red dash line square showed the cut part of the anterior bone with the thickness according to ossified ligament. And the red line indicated the position of grooves on both sides. (E) The red arrows showed the position of grooves on both sides. After tightening the screw in the middle vertebrae in a hoisting manner, the VOC moved forward. Then the space available for the cord were restored. (F‐H) Postoperative CT and MRI sagittal scan demonstrated satisfactory antedisplacement of VOC from C4 to C5. Cervical lordosis and space available for the cord were restored.

Anesthesia and exposure

After general anesthesia, supine position was taken, cervical oblique incision was made at the anterior right side to expose deep structures.

Fabrication of vertebral‐OPLL complex (VOC)

Discectomies were performed in involved levels. Then anterior parts of the vertebrae were cut according to the thickness of ossified ligament. According to the expected decompression width, a groove was created by a high‐speed drill on the anterior surface of vertebra at the left side.

Placement of cages, screws, and plate

Suitable cages were placed into intervertebral spaces, and a pre‐curved plated was fixed by screws to the caudal and cephalad vertebrae. Screws was inserted halfway for the temporary fixation on the middle vertebrae.

Isolation of VOC

Grooving was performed on the right side of the vertebrae to isolate the vertebrae and ossified ligament.

Hoist of VOC

The middle vertebrae and ossified mass were hoisted forward by tightening the screws mounted on the middle vertebrae. Finally, the incision was flushed, hemostasis and drainage were performed, and suture was finished layer by layer.

Postoperative management

The patients were ambulated after 2 postoperative days and fixed externally using a halo vest for 3 months.

Before operation, the thickness of ossification should be measured according to CT images, and the thickness of the bone to be removed in front of the vertebrae should be determined accordingly. At the same time, the width of ossification is of guiding significance for the width of grooving. Only when the width of grooving is larger than the width of ossification can the hoist be completed successfully.

In the laminoplasty group, surgery was performed as described by Hirabayashi et al. 7 . After determining surgical level, bony gutters with thin bottoms were drilled bilaterally at the border of the exposed laminae with a high‐speed drill. After the excision on dominant side was completed, the spinous processes and laminae are pushed laterally towards the other side. The lateral mass and lamina of the dominant side were fixed with mini plate. The patients were ambulated after two postoperative days and fixed externally using a collar for 3 months.

Clinical Evaluation

All patients were followed up for at least 24 months.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score. According to JOA score, the function of cervical spinal cord was scored from three aspects of motor, sensory, and bladder dysfunction. The highest score was 17 points, which was regarded as normal. JOA was used to evaluated neurologic status before and after the surgery.

Improvement rate (IR). IR was calculated as IR = (postoperative JOA score – preoperative JOA score/17‐preoperative JOA score)/100%. IR can reflect the improvement of the function of cervical spinal cord before and after treatment. IR can also correspond to efficacy: IR of 100% is considered as complete cure, more than 60% indicates marked effect, 25%–60% means effective treatment, and less than 25% is regarded as invalid treatment.

Complications were also recorded for the two groups.

Radiological Evaluation

Pre‐ and postoperative plain radiographs, CT scans, and magnetic resonance images (MRIs) were obtained in all patients. All radiologic images were reviewed on a single day and again 2 weeks later, in a different sequence, by two independent spine surgeons who were blinded to the patients, using a single picture archiving and communications system viewer and imaging software. To obtain reliable data and reduce errors, the average of at least three measurements was taken for each result.

Parameters were evaluated as follows (Fig. 3):

Fig. 3.

Radiological measurements for both groups. (A) the occupation rate (OR), (a) proper anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal, (b) thickness of the ossification at the level of the greatest canal narrowing. The OR is defined as (b) divided by (a). (B) space available for the cord (SAC). (C) anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the spinal cord. (D) cervical lordosis. Left, ACAF group (A1, B1, C1, and D1, respectively); right, Laminoplasty group (A2, B2, C2, and D2, respectively).

Occupying ratio (OR)

OR was defined as the thickness of OPLL divided by the anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the bony spinal canal on an axial CT image.

Cervical lordosis

Cervical lordosis was measured as the angle between lines parallel to the posterior aspect of the C2 and C7 vertebral body on lateral X‐ray.

Space available for the cord (SAC)

SAC was calculated on cross‐sectional MRI images in the midline.

Anteroposterior diameter of the spinal cord

AP diameter of the spinal cord was also calculated on cross‐sectional MRI images in the midline.

Spinal cord curvature

Spinal cord curvature was obtained via connecting midpoints of the spinal cord at each level from C2 to C7 on the sagittal MRI after operation 8 .

Extent and type of OPLL was also investigated on an axial CT image. Fusion was determined by CT at 1‐year follow‐up. CT criteria for fusion includes bridging bone inside or outside the graft and no lucency extending >50% of the graft‐host interface. Flexion and extension views of lateral plain X‐ray were performed to ensure no pseudoarthrosis exists.

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Mann–Whitney U test and chi square test were used to compare categorical variables including gender, extent levels of OPLL, classification of OPLL, complication, spinal cord curvature. Unpaired t test was used to compare continuous data including age, symptom duration, follow‐up duration, operative time, blood loss, JOA score, IR, OR, SAC, AP diameter of spinal cord, cervical lordosis. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

General Results

There were no significant differences in comparison of sex (13 males and eight females vs 17 males and 15 females), age (60.7 ± 7.2 years vs 57.6 ± 6.3 years), duration of symptoms (38.2 ± 10.4 months vs 35.7 ± 9.5 months), and type and extent of OPLL between ACAF and laminoplasty groups (Table 1). Operative time was higher in ACAF group (286.5 ± 25.3 min vs 178.2 ± 41.1 min, P < 0.05), but no significant difference was found between groups in terms of blood loss (291.6 ± 41.1 mL vs 318.3 ± 30.5 mL, P > 0.05). The clinical and radiologic results of ACAF and laminoplasty were compared as follows.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics in ACAF and laminoplasty groups

| ACAF | Laminoplasty | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.7 ± 7.2 | 57.6 ± 6.3 | >0.05 |

| Gender | >0.05 | ||

| Male | 13 | 17 | |

| Female | 8 | 15 | |

| Symptom duration, months | 38.2 ± 10.4 | 35.7 ± 9.5 | >0.05 |

| Follow‐up, months | 26.7 ± 1.6 | 28.5 ± 2.3 | >0.05 |

| Extent levels of OPLL | >0.05 | ||

| C3‐C5 | 6 | 5 | |

| C3‐C6 | 8 | 11 | |

| C4‐C6 | 5 | 7 | |

| C4‐C7 | 2 | 9 | |

| Classification of OPLL | >0.05 | ||

| Continuous type | 8 | 13 | |

| Segmental type | 3 | 3 | |

| Mixed type | 10 | 16 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. ACAF refers to anterior controllable antedisplacement and fusion.

P < 0.05, statistically significant.

Clinical Outcomes

JOA score and IR Preoperative JOA score was comparable (8.5 ± 1.6 vs 9.1 ± 2.5, P > 0.05). At the final follow‐up, mean JOA scores improved significantly in both groups (8.5 ± 1.6 vs 14.6 ± 2.1 in ACAF group, 9.1 ± 2.5 vs 12.8 ± 2.7 in laminoplasty group, P < 0.05both). Furthermore, the postoperative JOA scores (14.6 ± 2.1 vs 12.8 ± 2.7, P < 0.05) and IR (63.8 ± 12.1 vs 47.8 ± 26.4, P < 0.05) in ACAF group were greater than those in laminoplasty group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical outcomes in ACAF and laminoplasty groups

| ACAF | Laminoplasty | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time, min | 286.5 ± 25.3 | 178.2 ± 41.1 | <0.05* |

| Blood loss, mL | 291.6 ± 41.1 | 318.3 ± 30.5 | >0.05 |

| JOA score | |||

| Preoperative | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 9.1 ± 2.5 | >0.05 |

| Last Follow‐up | 14.6 ± 2.1 | 12.8 ± 2.7 | <0.05* |

| IR (%) | 63.8 ± 12.1 | 47.8 ± 26.4 | <0.05* |

| Complication | 2 (9.5%) | 10 (31.3%) | <0.05* |

| C5 palsy | 1 (4.7%) | 4 (12.5%) | <0.05* |

| Postoperative hematoma | 0 | 0 | |

| CSF leakage | 1 (4.7%) | 2 (6.3%) | >0.05 |

| Axial symptoms | 0 | 4 (12.5%) | <0.05* |

| Pseudarthrosis | 0 | 0 | |

| Spinal cord injury | 0 | 0 | |

| Implant complications | 0 | 0 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (range). JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association, IR improvement rate, CSF cerebrospinal fluid. ACAF refers to anterior controllable antedisplacement and fusion.

P < 0.05, statistically significant.

Radiographic Outcomes

OR and SAC. Postoperatively, mean OR (68.7 ± 4.9 vs 16.7 ± 5.9 in ACAF group, 62.9 ± 6.2 vs 40.9 ± 6.2 in laminoplasty group, P < 0.05 both) and SAC (73.3 ± 12.5 mm2 vs 150.8 ± 20.9 mm2 in ACAF group, 77.6 ± 10.5 mm2 vs 110.5 ± 23.2 mm2 in laminoplasty group, P < 0.05 both) improved significantly in both groups. However, postoperative OR (16.7 ± 5.9 vs 40.9 ± 6.2, P < 0.05) and SAC (150.8 ± 20.9 mm2 vs 110.5 ± 23.2 mm2, P < 0.05) were both significantly better in ACAF group than those in laminoplasty group (P < 0.05).

AP diameter of the spinal cord. The postoperative AP diameter of the spinal cord on cross‐sectional MRI was significantly greater in ACAF group than that in laminoplasty group (5.5 ± 1.1 mm vs 4.2 ± 1.1 mm, P < 0.05).

Cervical lordosis. At the final follow‐up, the cervical lordosis significantly decreased in the laminoplasty group (8.2° ± 2.1° vs 4.7° ± 3.2°, P < 0.05) and increased in the ACAF group (6.9° ± 4.2° vs 12.7° ± 2.7°, P < 0.05). Furthermore, the cervical lordosis in ACAF group was significantly greater than that in laminoplasty group (12.7° ± 2.7° vs 4.7° ± 3.2°, P < 0.05).

Spinal cord curvature. On sagittal MRI, the postoperative spinal cord curvature was classified into five types: type I, lordosis; type II, straight with no shifting; type III, straight with shifting; type IV, sigmoid; and type V, kyphosis 8 (Fig. 4). The spinal cord curvature was significantly better in ACAF group than that in laminoplasty group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Five types of spinal cord curvature after operation. (A) Type I, lordosis. (B) Type II, straight with no shifting. (C) Type III, straight with shifting. (D) Type IV, sigmoid. (E) Type V, kyphosis.

TABLE 3.

Radiographic outcomes in ACAF and laminoplasty groups

| ACAF | Laminoplasty | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR, % | |||

| Preoperative | 68.7 ± 4.9 | 62.9 ± 6.2 | >0.05 |

| Last Follow‐up | 16.7 ± 5.9 | 40.9 ± 6.2 | <0.05* |

| SAC, mm2 | |||

| Preoperative | 73.3 ± 12.5 | 77.6 ± 10.5 | >0.05 |

| Last Follow‐up | 150.8 ± 20.9 | 110.5 ± 23.2 | <0.05* |

| Diameter of spinal cord, mm | |||

| Preoperative | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 2.0 | >0.05 |

| Last Follow‐up | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | <0.05* |

| Cervical lordosis, ° | |||

| Preoperative | 6.9 ± 4.2 | 8.2 ± 2.1 | >0.05 |

| Last Follow‐up | 12.7 ± 2.7 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | <0.05* |

| Spinal cord curvature** | <0.05** | ||

| Lordosis (type I) | 10 | 9 | |

| Straight with no shifting (type II) | 11 | 8 | |

| Straight with shifting (type III) | 0 | 8 | |

| Sigmoid (type IV) | 0 | 4 | |

| Kyphosis (type V) | 0 | 3 |

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (range). OR occupying ratio, SAC space available for the cord, OPLL ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. ACAF refers to anterior controllable antedisplacement and fusion.

P < 0.05, (ACAF vs Laminoplasty).

P < 0.05, (good [lordosis, straight with no shifting] vs bad [straight with shifting, sigmoid, kyphosis] spinal cord curvature).

Complication

The overall complication rate was significantly lower in the ACAF group (P < 0.05). Complications after laminoplasty included C5 palsy in four cases, axial symptoms in four cases, and CSF leakage in one case, whereas complication after ACAF included C5 palsy in one case, and CSF leakage in one case. C5 palsy developed at 6 to 48 h postoperatively, and all recovered with conservative treatment. Administration of antibiotics and local compression of incision were performed for patients with CSF leakage, and the leakage stopped within 1 week in all patients. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs were used for the treatment of axial pain, and all patients were relieved of pain during follow‐up. All the patients achieved solid fusion without pseudarthrosis at the final follow‐up. No patients developed postoperative hematoma, spinal cord injury, or implant complications (Table 2).

Case Report

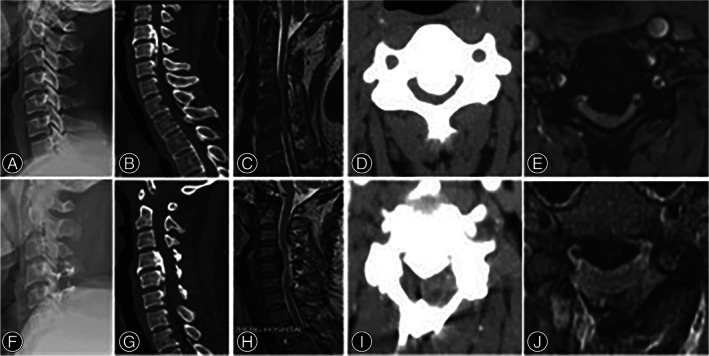

Classical cases were presented as follows.

As shown in Fig. 5, ACAF was performed from C3 to C6 in this female patient. Her OR decreased from 73.2% preoperatively to 4.5% postoperatively. The cervical lordosis was corrected from 5° preoperatively to 15° postoperatively. The spinal cord curvature was good (type I, lordosis) at the final follow‐up. Her JOA scores was 7 preoperatively and 15 postoperatively, with an IR of 80.0%.

Fig. 5.

A 55‐year‐old woman undergoing ACAF. (A) Lateral X‐ray showing the cervical lordosis was 5°. (B) sagittal CT of the cervical spine showing spinal stenosis from C3 to C5, and severe OPLL from C4 to C5. (C) Sagittal MRI showing spinal cord compression from C3 to C5, especially from C4 to C5. (D) Cross‐sectional CT showing the occupying rate of 73.2%. (E) The morphology of the spinal cord on cross‐sectional MRI was crescent and diameter of spinal cord was 2.5 mm. (F) Lateral X‐ray showing a surgery of ACAF from C3 to C6 and the cervical lordosis was 15°. (G) Sagittal CT and (H) MRI demonstrating the spinal canal returning to normal volume and sufficient decompression and the type of spinal cord curvature was Type I lordosis. (I) Cross‐sectional CT showing the occupying rate of 4.5%. (J) The morphology of the spinal cord on cross‐sectional MRI was cylinder and diameter of spinal cord was 5.8 mm.

Comparatively, laminoplasty was performed from C4 to C6 in this male patient (Fig. 6). His OR decreased from 70.5% preoperatively to 44.0% postoperatively. The cervical lordosis was 5° preoperatively and 6° postoperatively. The spinal cord curvature was unsatisfying (type IV, sigmoid) at the final follow‐up. His JOA scores increased from nine preoperatively and 11 postoperatively, with an IR of 25.0%.

Fig. 6.

A 57‐year‐old man undergoing laminoplasty. (A) Lateral X‐ray showing the cervical lordosis was 5°. (B) sagittal CT of the cervical spine showing spinal stenosis from C4 to C6, and severe OPLL from C4 to C5. (C) Sagittal MRI showing spinal cord compression from C4 to C6, especially from C4 to C5. (D) Cross‐sectional CT showing the occupying rate of 70.5%. (E) The morphology of the spinal cord on cross‐sectional MRI was boomerang and diameter of spinal cord was 2.3 mm. (F) Lateral X‐ray showing a surgery of laminoplasty from C4 to C6 and the cervical lordosis was 6°. (G) Sagittal CT and (H) MRI demonstrating partial recovery of spinal canal and the type of spinal cord curvature was Type IV sigmoid. (I) Cross‐sectional CT showing the occupying rate of 44.0%. (J) The morphology of the spinal cord on cross‐sectional MRI was crescent and diameter of spinal cord was 3.6 mm.

Discussion

The optimal approach for the treatment of OPLL remains controversial. Theoretically, anterior approach surgery is radical to decompress the spinal cord by directly removing all of the anterior pathogenic structures such as protruded discs, osteophyte or ossification lesion 9 . Actually, thorough resection of ossified mater requires repeated explorations by surgical instruments at the OPLL–dura interface, causing disturbances to dura and spinal cord. The procedure is complex and is associated with a high risk of complications, such as dural tear, graft extrusion, spinal cord injury. Especially for patients with multilevel and severe OPLL, anterior approach surgery remains a technical challenge 10 , 11 , 12 . Therefore, posterior approach obtained a more widespread application. Liu et al. suggested that laminoplasty may be a safer method of treatment for multilevel cervical myelopathy when the involved surgical segments were equal to three or more, for the sake of lower complications and reoperation rates, and less surgical trauma 13 , 14 . However, the posterior strategy only achieves indirect decompression by limited dorsal shift of spinal cord. As reported, posterior decompression tends to be unsatisfactory in OPLL patients with a large OR or kyphotic changes. Tani reported the neurological recovery rate of anterior approach was 58% ± 24% compared with 13% ± 39% of posterior approach for severe OPLL 15 . Iwasaki et al. reported that anterior decompression outperformed laminoplasty for the treatment of OPLL with OR more than 60% 16 . To combine the advantages and avoid the shortcomings of both approaches, ACAF has been introduced and utilized previously to achieve anterior direct decompression without removing the OPLL 6 , and our results indicated that ACAF achieved better clinical outcomes and lower complication rates than laminoplasty.

In the present study, mean JOA scores improved significantly in both groups. Furthermore, higher JOA score and greater IR were observed at the final follow‐up in ACAF group, suggesting that the direct decompression may achieve a better neurological recovery. The clinical outcomes were parallel to the radiographic evaluation. In ACAF, a wider symmetrical decompression was achieved to ensure enough space for dural sac and spinal cord, which contributes to higher AP diameter of the spinal cord and higher area of SAC.

Laminoplasty does not carry out intervertebral fusion, and thus retains the mobility of the cervical spine, but at the same time it cannot correct the unsatisfactory curvature of the cervical spine. It has been reported that the straight or kyphotic cervical curvature will lead to a poor effect of decompression in posterior approach because of insufficient back drift of spinal cord, and the risk of progressive ossification and kyphotic deformity cannot be ignored in long‐term follow‐up 17 , 18 . K‐line has been used to determine the surgical approach. A series of studies have demonstrated poor clinical outcomes after laminoplasty in OPLL patients with K‐line (−) and OR > 60% 19 , 20 , 21 . Like other anterior approaches, in spite of poor cervical curvature, ACAF can achieve direct decompression and effectively restore the cervical lordosis: the cervical lordosis increased to 12.7 ± 2.7 in this study. Several surgical techniques were used to correct cervical lordosis in patients accepting ACAF, including pre‐bending of titanium plate, intervertebral distraction and fusion, and hoisting of vertebrae. On the contrary, loss of the cervical lordosis has been observed in patients undergoing laminoplasty in our research. (cervical lordosis decreased from 8.2 ± 2.1to 4.7 ± 3.2), which is consistent with previous studies 22 , 23 .

C5 palsy has been reported in both anterior and posterior decompression, though it is more common in posterior procedures 24 . The incidences range from 14% to 18.4% after posterior decompression 25 . Nerve root traction caused by dorsal drift of the spinal cord after posterior decompression is one of the most widely accepted mechanisms, which is so called “tethering effect” 26 , 27 . Gu analyzed the significant risk factors of C5 palsy following posterior cervical decompression, which were: OPLL, narrowed intervertebral foramen, laminectomy, excessive spinal drift 25 . Therefore, the complication of C5 palsy is of great concern for multilevel OPLL with posterior decompression 28 , 29 , 30 . In this study, four patients (12.5%) developed C5 palsy and four patients (12.5%) had axial symptoms in the laminoplasty group. In contrast, the incidence in the ACAF group was significantly lower. During ACAF procedure, hoisting the VOC under control could avoid excessive drifting and restore natural position of spinal cord, which achieved “in situ” decompression 8 . Meanwhile, remaining integrality of ossified ligament without resection could further reduce the risk of nerve root injury during cutting process. This study shows that there is no significant difference in the incidence of CSF leakage between the two groups, indicating that ACAF can achieve similar safety as posterior surgery in the aspect of dural injury. The OPLL‐dura interface was not directly interfered by either ACAF or laminoplasty, which could refrain from the possible dural tear during resection of ossification. For patients existing adhesion between dura and ossification, dura will move forward together with VOC. At this time, it is necessary to prevent excessive hoist of the vertebra, otherwise it will increase the risk of dural tear.

Dynamic factor can also affect clinical outcomes. Nishida found that intraspinal stress increased when fusion had not been performed in the treatment of OPLL, which may result in deterioration of myelopathy 5 . Geol reported only fixation without decompression can be a simple, safe, rational method in the treatment of OPLL 31 . Therefore, when treating OPLL, fusion was thought to be a vital factor that can conquer the postoperative kyphotic change and dynamic factor 10 , 31 . Some reports have indicated that pseudarthrosis rates were lower following posterior procedures compared with anterior procedures 32 , 33 . As Leven reported, the risk factors of pseudarthrosis following cervical operation include: patient factors, multilevel fusions, type of bone graft, operative approach, and type of instrumentation 34 . In ACAF procedure, bilateral osteotomies may decline the blood supplying for fusion. However, the main blood supply is reserved by reserving the lateral posterior longitudinal ligament. In addition, a shape‐matched bone graft is implanted in the groove, which greatly increases the contact area between the implant and the vertebrae. Postoperatively, halo vest is applied to provide stable fixation in order to minimize the effects of dynamic factors. As a result, all the patients had solid fusion, with no pseudarthrosis in ACAF group.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this is a retrospective study without randomization. Therefore, there was a bias in selection of surgical procedure. Second, as a novel technique, learning curve of surgeons who perform ACAF may influence postoperative parameters, such as blood loss and operative time. Third, neurologic status was evaluated based on the JOA scoring system, which lacks a patient‐based evaluation. Forth, the present study is limited by a relatively small sample size. Despite these limitations, our study remains an inspiration, providing evidence that ACAF can be an alternative surgical procedure for cervical OPLL.

The patients included in this study were cases suffering from severe ossification (occupying rate ≥ 50%). The strategy of anterior direct decompression may be more suitable for such patients. This partly accounts for why the postoperative JOA score and IR of ACAF were better than that of laminoplasty in this study. However, as a classic cervical operation, laminoplasty has the advantages of high safety and short operative time, which is the first consideration for patients with good cervical curvature and K‐line positive ossification. How to standardize the selection criteria of operative method for OPLL is an important research direction in the future.

Our current study has shown that ACAF is more effective in treatment of multilevel severe OPLL compared with laminoplasty. It could provide sufficient decompression, better neurological recovery, lower complication rates, and better postoperative cervical lordosis and spinal cord curvature. Based on these results, ACAF is a very promising surgery strategy for multilevel severe OPLL.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81801226). Shandong Government Sponsored Study Abroad Program: 201903057.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Changzheng Hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Authors' Contributions

QK analyzed and interpreted the patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. XL and YT performed the examination of the data, and substantively revised the manuscript. JCS and YW conducted the acquisition of data. XL helped draft the work. YW and JCS proposed the idea of study design. JGS finished the final assessment of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Abiola R, Rubery P, Mesfin A. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: etiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of nonoperative and operative management. Global Spine J, 2016, 6: 195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Y, Yang L, Liu Y, Yang H, Wang X, Chen D. Surgical results and prognostic factors of anterior cervical Corpectomy and fusion for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e102008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edwards CC, Heller JG, Murakami H. Corpectomy versus Laminoplasty for multilevel cervical myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2002, 27: 1168–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fujimori T, Iwasaki M, Okuda S, et al. Long‐term results of cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament with an occupying ratio of 60% or more. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2014, 39: 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nishida N, Kanchiku T, Kato Y, Imajo Y, Taguchi T. Cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: factors affecting the effect of posterior decompression. J Am Paraplegia Soc, 2016, 40: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun J, Shi J, Xu X, et al. Anterior controllable antidisplacement and fusion surgery for the treatment of multilevel severe ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament with myelopathy: preliminary clinical results of a novel technique. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27: 1469–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirabayashi K, Watanabe K, Wakano K, Suzuki N, Satomi K, Ishii Y. Expansive open‐door laminoplasty for cervical spinal stenotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1983, 8: 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang H, Sun J, Shi J, et al. In situ decompression to spinal cord during anterior controllable Antedisplacement fusion treating degenerative kyphosis with stenosis: surgical outcomes and analysis of C5 nerve palsy based on 49 patients. World Neurosurg, 2018, 115: e501–e508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2015, 40: E675–E693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. An HS, Al‐Shihabi L, Kurd M. Surgical treatment for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2014, 22: 420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu W, Hu L, Chou PH, Liu M, Wang J. Comparison of anterior decompression and fusion versus laminoplasty in the treatment of multilevel cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2016, 12: 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epstein N. The surgical management of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in 51 patients. J Spinal Disord, 1993, 6: 432–454 discussion 54‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu X, Min S, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Wang H, Jin A. Anterior corpectomy versus posterior laminoplasty for multilevel cervical myelopathy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur Spine J, 2014, 23: 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu X, Wang H, Zhou Z, Jin A. Anterior decompression and fusion versus posterior laminoplasty for multilevel cervical compressive myelopathy. Orthopedics, 2014, 37: e117–e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tani T, Ushida T, Ishida K, Iai H, Noguchi T, Yamamoto H. Relative safety of anterior microsurgical decompression versus laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy with a massive ossified posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2002, 27: 2491–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwasaki M, Okuda SY, Miyauchi A, et al. Surgical strategy for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: part 2: advantages of anterior decompression and fusion over Laminoplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2007, 32: 654–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suda K, Abumi K, Ito M, Shono Y, Kaneda K, Fujiya M. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open‐door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2003, 28: 1258–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu G, Buchowski JM, Bunmaprasert T, Yeom JS, Shen H, Riew KD. Revision surgery following cervical laminoplasty: etiology and treatment strategies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2009, 34: 2760–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fujiyoshi T, Yamazaki M, Kawabe J, Endo T, Konishi H. A new concept for making decisions regarding the surgical approach for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2008, 33: E990–E993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koda M, Mochizuki M, Konishi H, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior decompression with instrumented fusion, and anterior decompression with fusion for K‐line (−) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Eur Spine J, 2016, 25: 2294–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim B, Yoon DH, Shin HC, et al. Surgical outcome and prognostic factors of anterior decompression and fusion for cervical compressive myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine J, 2015, 15: 875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu X, Chen Y, Yang H, Li T, Xu B, Chen D. Expansive open‐door laminoplasty versus laminectomy and instrumented fusion for cases with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and straight lordosis. Eur Spine J, 2017, 26: 1173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee C‐H, Jahng T‐A, Hyun S‐J, Kim K‐J, Kim H‐J. Expansive Laminoplasty versus laminectomy alone versus laminectomy and fusion for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: is there a difference in the clinical outcome and sagittal alignment? Clin Spine Surg, 2016, 29: E9–E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nassr A, Eck JC, Ponnappan RK, Zanoun RR, Donaldson WF III, Kang JD. The incidence of C5 palsy after multilevel cervical decompression procedures: a review of 750 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012, 37: 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gu Y, Cao P, Gao R, et al. Incidence and risk factors of C5 palsy following posterior cervical decompression: a systematic review. PLoS One, 2014, 9: e101933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sakaura H, Hosono N, Mukai Y, Ishii T, Yoshikawa H. C5 palsy after decompression surgery for cervical myelopathy: review of the literature. Spine (Phila pa 1976), 2003, 28: 2447–2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsuzuki N, Abe R, Saiki K, Zhongshi L. Extradural tethering effect as one mechanism of radiculopathy complicating posterior decompression of the cervical spinal cord. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1996, 21: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaneyama S, Sumi M, Kanatani T, et al. Prospective study and multivariate analysis of the incidence of C5 palsy after cervical laminoplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2010, 35: E1553–E1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Imagama S, Matsuyama Y, Yukawa Y, et al. C5 palsy after cervical laminoplasty: a multicentre study. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2010, 92: 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Minoda Y, Nakamura H, Konishi S, et al. Palsy of the C5 nerve root after midsagittal‐splitting laminoplasty of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2003, 28: 1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goel A, Nadkarni T, Shah A, Rai S, Rangarajan V, Kulkarni A. Is only stabilization the ideal treatment for ossified posterior longitudinal ligament? Report of early results with a preliminary experience in 14 patients. World Neurosurg, 2015, 84: 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fernyhough JC, White JI, LaRocca H. Fusion rates in multilevel cervical spondylosis comparing allograft fibula with autograft fibula in 126 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1991, 16: S561–S564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yonenobu K, Fuji T, Ono K, Okada K, Yamamoto T, Harada N. Choice of surgical treatment for multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1985, 10: 710–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leven D, Cho SK. Pseudarthrosis of the cervical spine: risk factors, diagnosis and management. Asian Spine J, 2016, 10: 776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]