Medicaid is the largest health care coverage program in the United States and serves as a core institution that shapes—and is shaped by—public health crises, racial injustice, and electoral politics. As such, Medicaid played a central role in 2020—a monumental year in American history—when COVID, extraordinary uprisings against racial violence, and a historic presidential election all strikingly converged. Examining Medicaid’s pivotal positioning at this nexus of politics, pandemic, and racial justice highlights fundamental constraints and possibilities in US health policy and underscores potentially fruitful directions for change under the incoming Biden administration.

MEDICAID AND COVID-19

Medicaid has played a vital role in responding to COVID-19. As the pandemic spread, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued emergency directives that made it easier for states to adapt Medicaid to emerging needs. As a result, every state in the nation altered its Medicaid program.1 States’ strategies for leveraging Medicaid to secure public health during the pandemic included adjusting eligibility requirements, streamlining enrollment procedures, expanding telehealth, increasing fee-for-service rates, and other steps to improve program accessibility, cost, and safety.2

Beyond these changes directly related to health care, Medicaid also functioned as a work support, making health coverage available to millions of low-wage essential workers who were at increased risk for exposure to the coronavirus. Even further, Medicaid offered critical countercyclical risk protection for people who experienced job loss during a floundering pandemic economy. Altogether, COVID-19 made Medicaid even more imperative for both the physical and economic health of the country.

MEDICAID AND RACIAL JUSTICE

COVID-19 also rendered Medicaid a more salient component of racial justice in the United States. This interrelationship has been amplified by the co-occurrence of a deeply unequal pandemic and a historic mass movement against racial violence. Heightened emphasis on racism in the context of COVID-19 magnified Medicaid’s standing as a racialized institution.3 Racialization involves “the extension of racial meaning to a previously racially unclassified relationship.”4(p13) Medicaid is racialized, despite being facially color-blind, because race has been a central factor shaping policies, discourse, design, implementation, and perceptions of it. So, even though racially neutral on paper, Medicaid is imbued with racial meaning and repercussions in practice.

Beneficiary disproportionality (i.e., racial imbalances in the composition of the populations that benefit from a policy) is one basic indicator of racialization. Disproportionality implies an “extension of racial meaning” because it can affect how policy is constructed by political elites, understood in the public imagination, implemented by bureaucrats, experienced by beneficiaries, and portrayed by media.5

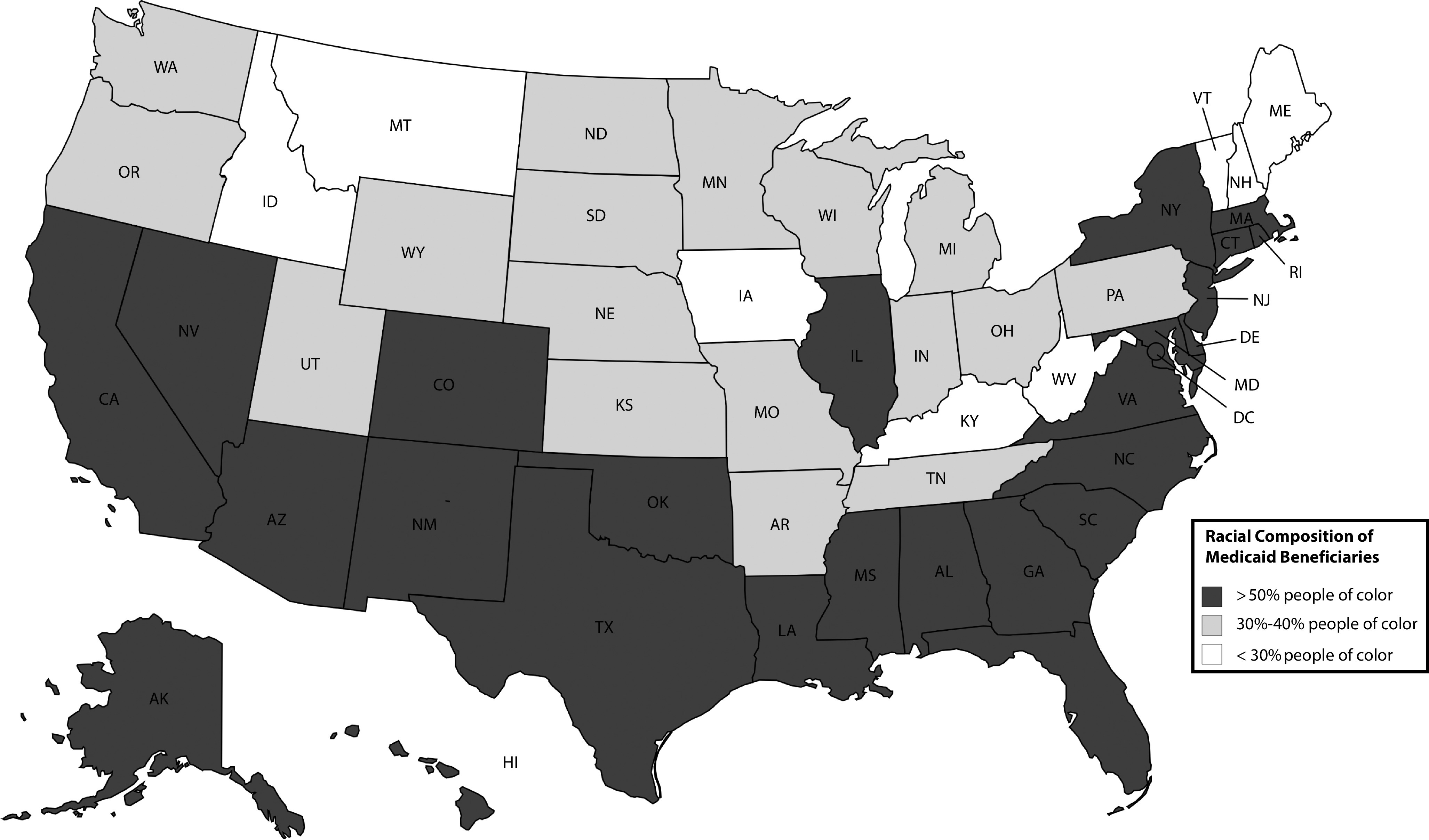

Consider Medicaid’s striking disproportionality. Nationwide, 20% of (nonelderly) Medicaid beneficiaries are Black, nearly 30% are Latinx, and almost 10% make up additional non-White racial and ethnic groups (4.3% Asian/Native Hawaiian, 1.1% American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.2% multiracial).6 As shown in Figure 1, Black, Latinx, Asian, Native, and multiracial Americans (comprehensively labeled as “people of color”) represent the majority of Medicaid beneficiaries in 25 states and sizeable portions of the beneficiary population in most of the remaining states. Only eight states have Medicaid populations with less than 30% people of color.

FIGURE 1—

The Racial Composition of Medicaid Beneficiaries: 2019

The racial disproportionality of Medicaid gives an important context for understanding its political limits. Medicaid has faced consistent political resistance via refusals to expand, calls for retrenchment, and attempts to implement punitive practices within the program. This resistance reflects a fraught politics that is also racialized—infused with racial meanings that shape its trajectory and contours.7 State opposition to Medicaid expansion is a foremost example. Existing evidence demonstrates that the Medicaid expansion prompted by the Affordable Care Act has narrowed racial disparities in access to care, health insurance coverage, and health care utilization (https://tinyurl.com/y62sxgzz). Yet, 12 states have not adopted the expansion. Seven of those states have Medicaid populations composed of more than 50% Black and Latinx beneficiaries (Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Florida). Even in the five remaining nonexpansion states (Wyoming, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Tennessee), Medicaid populations are substantially composed of people of color, ranging from 36% in Wyoming to 47% in South Dakota. In such places, expanding Medicaid is a decision akin to giving more resources to communities of color. Notwithstanding a pandemic that has saliently devastated those communities, states have steadfastly refused to commit such resources.

Even if facially neutral, such decisions reflect processes of racialization because they are influenced by racial attitudes, preferences, and demographics. Numerous studies confirm this. Racial divides in health care opinions widened dramatically as a result of President Obama being associated with the Affordable Care Act.8 Medicaid expansion decisions are correlated with state-level racial attitudes—lower racial sympathy and higher racial resentment are associated with stronger resistance to expansion.9 Medicaid also has variable public support on the basis of race, with Whites much less likely to support expansion and actual expansion outcomes positively correlated with White opinion, while uncorrelated with non-White attitudes.10 Governors who expand Medicaid are more likely to be rewarded politically when state Medicaid populations are more heavily composed of White beneficiaries.11 All of these patterns point to ways that racialized Medicaid politics has proven a consistent barrier to advancing and expanding Medicaid policy.

MEDICAID, VOTING, AND ELECTIONS

Even more broadly, Medicaid has crucial consequences for democracy. Medicaid expansion is associated with short-term boosts in voter turnout,12 whereas Medicaid retrenchment is associated with significant declines in rates of voting.13 More generally, Medicaid beneficiaries’ experiences with the program affect whether and how they participate in politics.14

The repercussions of the relationships between Medicaid, race, and politics were on prominent display during the 2020 election. Survey data show strong support for Medicaid expansion in swing states that have not yet expanded such as Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin (https://tinyurl.com/y5dxfdaw). However, that support is strikingly divided along partisan lines, with Republicans much more likely to oppose expansion. Significant racial chasms underlie these partisan divides. People of color make up roughly 40% of Democratic voters but only 19% of Republican voters (https://tinyurl.com/yy35wbf5). Overwhelmingly, White Republican constituents drive opposition to Medicaid expansion.

Recognizing this dynamic creates opportunities for anticipating potential policy windows. Take Georgia, for instance. Though Georgia is typically considered a “red” state, Stacy Abrams—a Black woman and Democrat—only narrowly lost the state’s gubernatorial election in 2018. Then, in 2020 and early 2021, Georgia voters made history by selecting a Democratic presidential candidate (Joe Biden) and two Democratic senators, one of whom (Raphael Warnock) is now the South’s first Black Democratic senator. While these wins are not likely the harbinger of a new progressive majority, they do signal the possibility of a shift in Medicaid politics and indicate prospects for political coalitions that move the needle on Medicaid expansion. Georgia is just one example. The larger point is that Medicaid politics are inextricably linked to electoral politics and democracy—and those linkages are racialized.

POLITICS, PANDEMIC, AND RACIAL JUSTICE

The nexus of politics, pandemic, and racial (in)justice points to the importance of viewing Medicaid capaciously—not only as a policy mechanism for improving health outcomes among vulnerable populations but also as a constrained product of racialized politics and as an often-overlooked producer of such politics. Only by understanding all of these facets of Medicaid can we adequately grapple with how to improve health policy and advance racial justice.

As a new presidential administration takes hold, making progress on health policy will require attentiveness to Medicaid politics and its racialized contours. In this vein, a first-order priority for the incoming administration should be to reverse the suite of punitive Medicaid waivers that have emerged in the last four years. The most salient waivers include work reporting requirements, lockout penalties that prevent beneficiaries from accessing care, delays to the start of coverage until after premiums are paid, elimination of retroactive coverage, and loss of presumptive eligibility. These provisions undermine both political participation and health equity.

Punitive waivers lead to disenrollment, which is associated with decreased rates of voting. Political demobilization can also occur as a consequence of the negative experiences engendered by burdensome and stigmatizing administrative processes. Even further, waivers have racially disparate outcomes. Work requirements, for example, affect Black policy beneficiaries more negatively.15 Federal intervention to eliminate onerous and racially unequal work reporting requirements is especially crucial because Black women—those most affected—are among the most engaged voting population in a number of the states that are implementing work requirements.

Beyond waivers, the larger takeaway is that attentiveness to both racial justice and politics will be critical for expanding and enhancing Medicaid. This is especially true in the context of COVID-19. In the coming months, the Biden administration will face essential decisions about how to distribute health resources (like vaccines), how to strengthen health infrastructure (like the public health workforce), and how to best leverage executive agencies (like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). These and many other health policy decisions will directly and indirectly affect Medicaid. The dynamics highlighted in this essay underscore the imperative to remain attuned to racialized political realities and to intentionally prioritize racial equity.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author does not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Schubel J. States are leveraging Medicaid to respond to COVID-19. Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. May 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-are-leveraging-medicaid-to-respond-to-covid-19. Accessed November 18, 2020.

- 2.Gifford K, Lashbrook A, Barth S . S. tate Medicaid programs respond to meet COVID-19 challenges: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2020 and 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation. October 14, 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/state-medicaid-programs-respond-to-meet-covid-19-challenges. Accessed November 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michener J. The politics of Medicaid policy and racial justice. Data for Progress Blog. November 16, 2019. Available at: https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2019/11/16/the-politics-of-medicaid-policy-and-racial-justice. Accessed November 19, 2020.

- 4.Omi M, Winant H. Racial Formation in the United States. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michener J. Policy feedback in a racialized polity. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(2):423–450. doi: 10.1111/psj.12328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. Distribution of the nonelderly with Medicaid by race/ethnicity. October 23, 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-distribution-nonelderly-by-raceethnicity/view/print/?currentTimeframe=0&print=true&sortModel=%7B%22colId%2 2:%22Multiple%20Races%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D. Accessed November 19, 2020.

- 7.Michener J. Race, politics, and the Affordable Care Act. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(4):547–566. doi: 10.1215/03616878-8255481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tesler M. The spillover of racialization into health care: how president Obama polarized public opinion by racial attitudes and race. Am J Pol Sci. 2012;56(3):690–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00577.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanford D, Quadagno J. Implementing ObamaCare: the politics of Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act of 2010. Sociol Perspect. 2016;59(3):619–639. doi: 10.1177/0731121415587605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grogan CM, Park SE. The racial divide in state Medicaid expansions. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(3):539–572. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3802977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fording RC, Patton DJ. Medicaid expansion and the political fate of the governors who support it. Policy Stud J. 2019;47(2):274–299. doi: 10.1111/psj.12311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haselswerdt J. Expanding Medicaid, expanding the electorate: the Affordable Care Act’s short-term impact on political participation. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(4):667–695. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3856107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haselswerdt J, Michener J. Disenrolled: retrenchment and voting in health policy. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2019;44(3):423–454. doi: 10.1215/03616878-7367012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michener J. Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brantley E, Pillai D, Ku L. Association of work requirements with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation by race/ethnicity and disability status, 2013–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205824. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]