Introduction

In a similar vein to cardiology or radiology, the term interventional psychiatry has been proposed to describe treatments that are more procedural and invasive than general medical care within that specialty.1 Descriptions of approaches that fall within interventional psychiatry have emphasized anatomically-guided direct-to-brain treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD) such as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). There has been a veritable explosion of interest in interventional psychiatry in the last decade, but the rate of competency of trainees to deliver these treatments is understudied.

This study aims to assess the self-reported experience, knowledge, and efficacy of a representative national sample of physicians who have completed or are nearing completion of their psychiatry residency programs and to administer evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for MDD including ECT and rTMS. The overarching goals of this study are to create a snapshot of the emerging psychiatric workforce’s ability to perform deliver EBTs for MDD, including ECT and rTMS, and to serve as a needs assessment of training in interventional psychiatry, informing curriculum development in this area from the trainee perspective.

Method

Participants were 5th-year residents of psychiatry programs from across Canada and international medical graduates preparing for their licensing examinations to practice psychiatry in Canada who attended the 2019 P. Chandarana London Psychiatry Review Course at Western University in London, Ontario. Participants were asked about their self-efficacy, satisfaction, and degree of exposure to recommendations from the 2016 MDD CANMAT (www.canmat.org) guidelines that received 1st-line recommendations. Demographic and training characteristics were collected to characterize the sample. Multiple logistic regression was used to model levels of experience administering ECT with odds of self-reported competence. Participants received a $20 gift certificate to compensate for their time. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Results

In this study, 162 participants completed the survey (73.3% of all attendees; 162/221), including 57.5% (119/207) of the PGY-5 psychiatry residents in the country (https://www.carms.ca/match/r-1-main-residency-match/program-descriptions/). The majority of people completing the survey were female (61.5%), graduated from a Canadian medical school (66.7%), attended a Canadian psychiatry residency program (90.1%), and anticipated working in a hospital setting (53.7%).

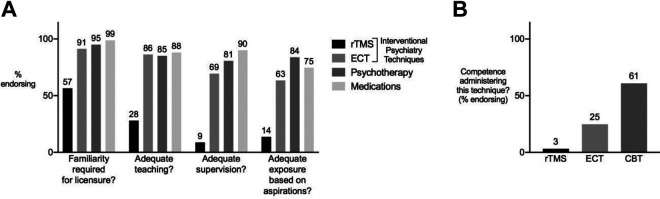

The majority of participants felt that familiarity with ECT (91.3%) and rTMS (56.5%) should be required for licensure in psychiatry (Figure 1A); however, only a small percentage were able to achieve competency during their training (ECT: 24.3%; rTMS 3.1%; Figure 1B). Greater percentages of participants felt that exposure to ECT or rTMS was inadequate compared to psychotherapy and medications, with gaps identified in teaching and especially in receiving supervision in application of the Interventional psychiatry approaches. Administering ECT more than 10 times in residency was significantly associated with perceived ECT competence compared administering it 0 to 10 times (OR = 17.6; 95 CI, 5.8 to 52.7; P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

(A) Percentage of participants agreeing with statements regarding their training in recommended 1st-line treatment options for MDD during their residency. (B) Percentage of participants endorsing competence in administering rTMS, ECT, or CBT at the end of their residency. CBT = cognitive behavioural therapy; ECT = electroconvulsive therapy; MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Discussion

This study represents the largest known survey in the literature of residents’ competence and training experiences in Interventional Psychiatry. The results support that the emerging psychiatric workforce in this country is eager and receptive to receive further clinical experiences in their residency training to gain proficiency in ECT and rTMS for the treatment of MDD.

The rates of competency in ECT have been stagnant over the past 3 decades.2,3 Given the established efficacy of ECT as the gold-standard approach in treating acute depression, perceived ECT competency in just under a quarter of the emerging psychiatric workforce is particularly concerning. The results of this study suggest a way forward from the learners’ perspective, with more opportunities to receive supervision being especially valued. Additionally, this survey indicates that directly administering ECT at least 10 times may be considered a minimum benchmark to achieve self-perceived competency in this technique.

The results of this survey also provide evidence for the first time for large unmet needs when it comes to rTMS training in this country. Although the majority endorsed that familiarity with rTMS should be required for licensure, only 3.1% reported achieving this at the end of their training. The rapid advances in evidence for rTMS in the past decade may be outpacing the ability of residency training to provide sufficient teaching, supervision, and exposure to this treatment, resulting in a shortage of psychiatrists who are adequately trained in providing rTMS. These results can inform curricular design during the period of shift toward competency-based education.4

Conclusion

In summary, the emerging psychiatric workforce in this country appears eager for further didactic teaching, supervision, and experiential learning in interventional psychiatry treatments for MDD, in keeping with the general sentiment by trainees for inclusion of more neuroscience-based education.5 During a time of rapid growth in the evidence-base for interventional psychiatry, shifts in postgraduate medical education are needed to equip the next generation of psychiatrists with experiences in ECT and rTMS to ensure the translatability of these findings to the population level.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, questionnaire for Interventional Psychiatry: An Idea Whose Time Has Come? by Peter Giacobbe, Enoch Ng, Daniel M. Blumberger, Zafiris J. Daskalakis, Jonathan Downar, Carla Garcia, Clement Hamani, Nir Lipsman, Fidel Vila-Rodriguez and Mark Watling in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of the P. Chandarana London Psychiatry Review Course for their help in the distribution and collection of the surveys and Dr. Annie Zhu for her help in inputting data.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Giacobbe has received research support from the CIHR, NIH and Veteran’s Affairs Canada. He has been an unpaid consultant for St. Jude Medical and has served on an advisory board for Janssen and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Ng reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Blumberger has received research support from CIHR, NIH, Brain Canada, and the Temerty Family through the CAMH Foundation and the Campbell Family Research Institute. He received research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. He is the site principal investigator for three sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He also receives in-kind equipment support from Magventure for two investigator-initiated research. He received medication supplies for an investigator-initiated trial from Indivior. Dr. Daskalakis has received research support from CIHR, NIH, Brain Canada, and the Temerty Family through the CAMH Foundation and the Campbell Family Research Institute. He received research support and in-kind equipment support for an investigator-initiated study from Brainsway Ltd. He is the site principal investigator for sponsor-initiated studies for Brainsway Ltd. He also receives in-kind equipment support from Magventure for investigator-initiated research. Dr. Downar has received research support from CIHR, NIMH, Brain Canada, the Canadian Biomarker Integration Network in Depression, the Ontario Brain Institute, the Klarman Family Foundation, the Arrell Family Foundation, the Edgestone Foundation, a travel stipend from Lundbeck and from ANT Neuro, an advisor to BrainCheck and in-kind equipment support for this investigator-initiated trial from MagVenture. Dr. Garcia reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Hamani was part of an advisory board for Medtronic unrelated to this work. Dr. Lipsman reports no financial relationships with commercial interests. Dr. Vila-Rodriguez receives research support from CIHR, Brain Canada, Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, and in-kind equipment support for this investigator-initiated trial from MagVenture. He has participated in an advisory board for Janssen. Dr. Watling has received an honorarium from Lundbeck in the past 2 years.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

ORCID iD: Peter Giacobbe, MD, MSc, FRCPC  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6642-6221

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6642-6221

Daniel M. Blumberger, MD, MSc, FRCPC  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8422-5818

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8422-5818

Supplemental Material: The supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Williams NR, Taylor JJ, Snipes JM, Short EB, Kantor EM, George MS. Interventional psychiatry: how should psychiatric educators incorporate neuromodulation into training. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(2):168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yuzda E, Parker K, Parker V, Geagea J, Goldbloom D. Electroconvulsive therapy training in Canada: a call for greater regulation. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(10):938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patry S, Graf P, Delva NJ, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy teaching in Canada: cause for concern. J ECT. 2013;29(2):109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Danilewitz M, Ainsworth NJ, Liu C, Vila-Rodriguez F. Towards competency-based medical education in neurostimulation. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44(6):775–778. doi:10.1007/s40596-020-01195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hassan T, Prasad B, Meek BP, Modirrousta M. Attitudes of psychiatry residents in Canadian universities toward neuroscience and its implication in psychiatric practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(3):174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, questionnaire for Interventional Psychiatry: An Idea Whose Time Has Come? by Peter Giacobbe, Enoch Ng, Daniel M. Blumberger, Zafiris J. Daskalakis, Jonathan Downar, Carla Garcia, Clement Hamani, Nir Lipsman, Fidel Vila-Rodriguez and Mark Watling in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry