Abstract

The globalization of medical research and global health’s increasing popularity worldwide have resulted in greater geographic, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity of studies published in the scientific literature. Yet the geographic distribution, authorship representation, and subject trends among Low-/Low-Middle-Income Country (LIC/LMIC)-based scientific publications remain largely unknown. This analysis assesses these gaps in knowledge. We performed a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of all scientific articles published between January 2014 and June 2016 in the four most prominent general medicine and five most prominent general global health journals based on impact factor. The African region, containing 24% of the global LIC/LMIC population, accounted for 49.9% of all publications. Corresponding authors with either exclusive or joint appointment to a LIC/LMIC institution were present in 26.2% of all included articles. Over one-quarter (28.8%) of all publications did not list a local author. Nearly two-thirds (62.1%) of articles published in global health journals and roughly half (52.4%) in general medicine journals involved infectious diseases. Non-HIV infectious disease studies were by far the most frequent subject areas across all journals. The trends identified in this study may help to inform the evolution and prioritization of future research efforts, thereby allowing global health to remain truly global.

Keywords: Global health, publication, geographic, low income, low-middle income, journal, impact factor, equity

1. INTRODUCTION

Global health is a rapidly expanding, cross-disciplinary area of medicine that generally focuses on poor and vulnerable populations across diverse geographic regions with a particular emphasis on low- and middle-income countries [1]. Recognizing the disproportionate burden of treatable and preventable diseases in such settings [2], the globalization of medical research and global health’s increasing popularity worldwide have resulted in greater geographic, ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of studies published in the scientific literature [3]. Despite this trend, the overwhelming majority of scientific publications still stem from High-Income and Upper-Middle-Income Countries (HICs and UMICs, respectively) with sparse representation from Low- and Low-Middle-Income Countries (LICs and LMICs, respectively) [4–6]. Consequently, conditions relevant to HICs and UMICs are overrepresented and those affecting LICs and LMICs are underrepresented in the medical literature [7]. Similarly, numerous studies have outlined the low rates of LIC and LMIC authorship on scientific publications, particularly in high-impact journals and even for studies performed in LIC and LMIC settings [8,9].

In light of these gaps, there is increased recognition within the scientific community of the need to conduct and publish more high-quality research in traditionally underrepresented geographic locations. In recent years, there has been a steady increase in the number of global health-specific scientific journals, global health-oriented interest groups within professional societies, and academic partnerships between HIC and LIC/LMIC institutions. Yet the geographic distribution, authorship representation, and subject trends among LMIC-based scientific publications remain largely unknown. This analysis assesses these limitations in knowledge by asking a simple question: where do LIC/LMIC publications and authors come from? Elucidating patterns in the literature can highlight discrepancies that may inform the diversification efforts of the scientific community.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We divided the 5-year period between January 2014 and December 2018 into “early” (first 30 months) and “late” (latter 30 months) periods. The year 2014 was chosen as the analysis start date as it was the first full year of publication of the preeminent global health journal, Lancet Global Health. We performed a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of all scientific articles published in the early period (between January 2014 and June 2016) in the four most prominent general medicine and five most prominent general global health journals based on the Journal Citation Report impact factor (Table 1). General medicine journals were chosen because of their wide readership and broad influence on medical practice and health policy. Global health journals were chosen because they were more likely to publish studies from LIC/LMIC locations. When impact factor was unavailable, it was extrapolated from the parent journal. All articles originating in or pertaining to LICs or LMICs were screened and recorded in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Redmond, USA). LICs and LMICs were categorized according to 2014 World Bank country and lending group data [10]. Each country was then grouped by geographic region using World Health Organization (WHO) designation [11]. For each article, the study’s location, topic, and author institutional affiliations were noted. Only original research studies involving a LIC/LMIC were included for final analysis. Studies involving multiple WHO regions were included if at least one LIC/LMIC was listed as participating. Reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries, non-human studies, and those performed exclusively in UMICs and HICs were excluded. Original research studies related to Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) were also excluded to minimize bias because of the public prominence of the 2014 West African EVD epidemic, which likely prompted research that otherwise would not have been performed.

Table 1.

Description of journals and impact factorsa

| General medicine journals | Impact factor | Global health journals | Impact factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | |||

| New England Journal of Medicine | 55.873 | Lancet Global Health | 10.042 |

| The Lancet | 45.217 | Bulletin of the World Health Organization | 5.089 |

| Journal of the American Medical Association | 35.289 | PLOS One Global Healthb | 3.234 |

| British Medical Journal | 17.445 | American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene | 2.699 |

| Tropical Medicine and International Health | 2.329 | ||

| 2015 | |||

| New England Journal of Medicine | 59.558 | Lancet Global Health | 14.722 |

| The Lancet | 44.002 | BMC Medicine for Global Healthc | 8.005 |

| Journal of the American Medical Association | 37.684 | Bulletin of the World Health Organization | 5.296 |

| Annals of Internal Medicine | 16.593 | PLOS One Global Healthb | 3.057 |

| American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene | 2.453 | ||

| 2016 | |||

| New England Journal of Medicine | 72.406 | Lancet Global Health | 17.686 |

| The Lancet | 47.831 | Bulletin of the World Health Organization | 4.939 |

| Journal of the American Medical Association | 44.405 | Tropical Medicine and International Health | 2.850 |

| British Medical Journal | 20.785 | PLOS One Global Health | 2.806 |

| Journal of Global Health | 2.707 | ||

Impact factors for each calendar year are determined the following year.

Impact factor extrapolated from parent journal, PLOS One.

Impact factor extrapolated from parent journal, BMC Medicine.

3. RESULTS

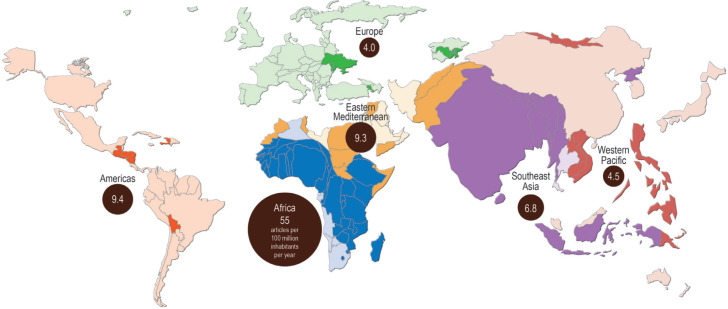

Of 1592 articles reviewed in four general medical and five global health journals, 878 articles were included in the final analysis. Table 2 and Figure 1 summarize the distribution of articles based on WHO geographic region. The African region, which contained 46% of the world’s LICs/LMICs and 24% of the global LIC/LMIC population in 2014, accounted for 49.9% of all publications. Of the publications from the African region, 416 (26.2%) were performed in the six East African Community countries: Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda (Figure 2). In contrast, the Southeast Asian region, which contained 11% of the world’s LICs/LMICs and 53% of the global LIC/LMIC population in 2014, constituted 13.6% of all publications, while the Eastern Mediterranean region, which contained 11% of the world’s LICs/LMICs and 12% of the world’s LIC/LMIC population in 2014, represented 2.2% of all publications. General medicine journals were more apt to publish large, transnational studies involving four or more WHO geographic regions.

Table 2.

Single-region publications compared with 2014 regional population distributions

| WHO region | % World countries | % World LICs/LMICs | Population, total (% world population) | Population, LIC/LMIC (% world LIC/LMIC population) | Publications, all journals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 24 | 46 | 927,619,905 (13.1) | 80,819,422 (23.7) | 433 (49.5) |

| Americas | 18 | 10 | 962,480,761 (13.6) | 65,577,392 (1.9) | 41 (4.7) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 11 | 11 | 611,900,462 (8.6) | 424,344,548 (12.5) | 19 (2.2) |

| Europe | 27 | 9 | 905,148,302 (12.8) | 100,625,500 (2.9) | 4 (0.5) |

| Southeast Asia | 6 | 11 | 1,854,322,868 (26.2) | 1,786,967,343 (52.5) | 120 (13.7) |

| Western Pacific | 14 | 13 | 1,819,337,057 (25.7) | 221,377,971 (6.5) | 54 (6.2) |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 7,080,809,355 | 3,403,712,196 | 671 (76.6)a |

Total does not add up to 100% due to exclusions noted above. Studies (N = 204; 23.4%) involving two or more regions are not reported.

LIC, Low-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country.

Figure 1.

Distribution of global health publications per 100 million inhabitants by World Health Organization geographic region. Each region is scaled by 2014 World Bank population. Dark colors within each region represent LICs and LMICs, light colors represent UMICs and HICs. Credit: Hugo Ahlenius, https://nordpil.com

Figure 2.

Averaged annual distribution of global health publications by LIC/LMIC. Credit: Hugo Ahlenius, https://nordpil.com

Table 3 summarizes authorship trends. Corresponding authors with either exclusive or joint appointment to a LIC/LMIC institution were present in 26.2% of all included articles. Global health journals more frequently had LIC/LMIC corresponding authors compared with general medicine journals. At least one author with an affiliation to a LIC/LMIC institution was listed in 71.2% of all studies with roughly equivalent frequencies between global health and general medicine journals. Stated another way, 28.8% of all publications did not list a local author.

Table 3.

Author institutional affiliation by year and type of publication

| Affiliation | All journals/years | General medical journals | Global health journals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016a | 2014 | 2015 | 2016a | ||

| N = 876 | N = 39 | N = 55 | N = 45 | N = 341 | N = 284 | N = 112 | |

| Corresponding author exclusively LIC/LMIC (%) | 176 (20.0) | 5 (12.8) | 9 (16.4) | 6 (13.3) | 66 (19.4) | 64 (22.5) | 26 (23.2) |

| Corresponding author joint LIC/LMIC + HIC (%) | 54 (6.2) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | 31 (9.1) | 7 (2.5) | 9 (8.0) |

| Other author from LIC/LMIC (%) | 624 (71.2) | 36 (92.3) | 36 (65.5) | 22 (48.9) | 263 (77.1) | 213 (75.0) | 54 (48.2) |

January through June.

LIC, low-income country; LMIC, low-middle-income country; HIC, high-income country.

Article subject trends are summarized in Table 4. Studies enrolling adults were most popular across all journals. Nearly two-thirds (62.1%) of articles published in global health journals and roughly half (52.4%) of general medicine journals pertained to infectious diseases, including HIV. Non-HIV infectious disease studies were by far the most frequent subject areas across all journals, followed by public health/epidemiology and maternal/reproductive health. This trend was similar for global health journals. General medicine journals more often published studies on noncommunicable diseases, whereas global health journals were more likely to publish articles related to neglected tropical diseases. The least frequent subject areas across all journals were acute care, health policy, and mental health. There were no original research studies on biomedical ethics in any journal.

Table 4.

Study populations and subject areas of included articles

| All journals/years | General medicine journals | Global health journals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016a | 2014 | 2015 | 2016a | ||

| N = 878 | N = 42 | N = 55 | N = 45 | N = 341 | N = 284 | N = 112 | |

| Study populationb | |||||||

| Adult (%) | 536 (61.0) | 31 (73.8) | 22 (40.0) | 33 (73.3) | 236 (69.2) | 159 (56.0) | 56 (50.0) |

| Pediatric (%) | 272 (31.0) | 11 (26.2) | 23 (41.8) | 8 (17.8) | 90 (26.4) | 119 (41.9) | 21 (18.8) |

| Neonatalc (%) | 86 (9.8) | 4 (9.5) | 15 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (4.7) | 26 (9.2) | 25 (22.3) |

| Subject | |||||||

| Maternal and reproductive health (%) | 129 (14.7) | 7 (16.5) | 13 (23.6) | 5 (11.1) | 35 (10.8) | 38 (13.4) | 31 (27.7) |

| Non-HIV infectious diseases (%) | 348 (39.6) | 26 (61.9) | 17 (30.9) | 10 (22.2) | 191 (56.0) | 87 (30.6) | 17 (15.2) |

| HIV (%) | 80 (9.1) | 9 (21.4) | 5 (9.1) | 3 (6.7) | 34 (10.0) | 21 (7.4) | 9 (8.0) |

| Neglected tropical diseases (%) | 104 (11.8) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (5.5) | 1 (2.2) | 50 (14.7) | 42 (14.8) | 7 (6.3) |

| Acute cared (%) | 19 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (8.9) | 6 (1.8) | 4 (1.4) | 3 (2.7) |

| Noncommunicable diseases (%) | 109 (12.4) | 7 (16.7) | 24 (43.6) | 17 (37.8) | 26 (1.8) | 24 (8.5) | 11 (9.8) |

| Mental health (%) | 17 (1.9) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.8) | 6 (2.1) | 2 (1.8) |

| Health systems (%) | 111 (12.6) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (8.9) | 55 (16.1) | 32 (11.3) | 15 (13.4) |

| Health policy (%) | 19 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.6) | 6 (2.1) | 4 (3.6) |

| Public health and epidemiology (%) | 231 (26.3) | 11 (26.2) | 8 (14.5) | 7 (15.6) | 105 (30.8) | 70 (24.6) | 30 (26.8) |

| Ethics (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

January through June.

Values may not add to 100% because of overlap of study populations within included articles.

Defined as ≤30 days after delivery.

Defined as trauma, emergency, and intensive care.

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

4. DISCUSSION

This study has several important findings. First, half of all scientific studies were conducted in the African region during the study period. African representation is proportional when adjusted for percent of the world’s LICs/LMICs, but is overrepresented when adjusted for the global LIC/LMIC population. Conversely, other regions, particularly Southeast Asia, are underrepresented when adjusted for global LIC/LMIC population. A surprisingly large percentage of publications involved multiple geographic regions. Second, LIC/LMIC corresponding authorship remains limited, whereas a sizable percentage of LIC/LMIC studies contain no LIC/LMIC co-authors. Third, there remains a strong emphasis on infectious disease topics across all journals, whereas general medicine journals publish more often on noncommunicable diseases.

There are potential linguistic and historical explanations for the preponderance of studies from the African region. Linguistically, a large proportion of contemporary academic global health stems from English-speaking HICs [12], a circumstance that may create a natural research affinity toward Anglophone regions in sub-Saharan Africa. Historically, much of modern global health’s roots developed over the past three decades from the HIV epidemic, which has had the greatest impact in sub-Saharan Africa. As research beyond HIV expands to other diseases and conditions in LICs/LMICs, present-day studies naturally may continue to use established African research infrastructure and funding mechanisms. The heavy emphasis on certain African regions, however, risks reducing the generalizability of study results and overlooking the incredible environmental, nutritional, cultural, genetic, and microbial diversity of the African continent itself. Moreover, sub-Saharan Africa is not necessarily representative of all LIC/LMIC environments. Consequently, the global health movement must make a concerted effort to balance geographic representation within and between geographic regions.

Limited LIC/LMIC authorship has been well-documented in the literature [8], so our finding that nearly 30% of studies lacked any local author was not surprising. Similar trends have been detailed in the global surgical literature [13]. The reasons for this trend remain unclear, but possibilities include: (1) reduced awareness of authorship criteria among LIC/LMIC partners [14]; (2) authors with multiple affiliations who may choose to list only their non-LIC/LMIC institution [15]; (3) authors who live and work in the LIC/LMIC environments being studied but who hold only non-LIC/LMIC academic affiliations [9]; and (4) no local collaborator. The first and fourth possibilities remain likely, even though non-LIC/LMIC investigators typically must establish partnerships with LIC/LMIC clinicians, administrators, and Ministries of Health to launch and maintain their research. A survey of surgical and anesthesia trainees at a major teaching hospital in Uganda, for example, revealed no listed co-authorship on academic publications, despite 28% of survey respondents participating in research overseen by international partners [16]. Although HIC–LMIC partnerships may open doors for some LIC/LMIC researchers, many other related factors may stifle the academic advancement of LIC/LMIC-based scientists. Traditional “North–South” institutional collaborations may have unbalanced and inequitable power dynamics that marginalize local scientists for myriad reasons [17]. Similarly, medical journals can hinder the progress of these collaborations by, for example, limiting LIC/LMIC editorial board representation, which may lead to inadequate understanding of LIC/LMIC-based research in the context of the material and human resource limitations that often exists in these environments [17]. Substantial publication costs may serve as another barrier [18]. Efforts to improve LIC/LMIC first-author and senior-author representation is important as a marker of scientific research equity. Perhaps most critical is ensuring that these efforts promote retention of local scientists, accept the realities of local contexts, and avoid “trickle down science” that disproportionately benefits non-LIC/LMIC investigators [8,19].

We were encouraged to see that noncommunicable disease articles were particularly prevalent among general medicine journals. Addressing noncommunicable diseases has been emphasized by the United Nations and other international health bodies given their very high burden in LICs and LMICs [20]. The very low prevalence of acute care studies, despite their relevance to LICs/LMICs, likely reflects the traditionally low global prioritization of this subject area due to what many consider to be expensive and extraordinary care [21]. This situation is compounded by a dearth of information regarding the clinical effectiveness, cost effectiveness, return on investment, and impact on outcomes of various acute care components. Recently, high-level international collaborations have started to develop an acute care research framework that promises to address these gaps [22].

This study has several limitations. First, “global health journal” is poorly defined. We selected journals with particularly wide recognition among global health practitioners. Our findings may have been different had we included more topic-specific journals, such as those that deal primarily with malaria or neglected tropical diseases. Second, two global health journals included in this study lacked impact factors, reflecting the relative youth of academic global health as a distinct entity. Given the prominence of their parent journals, however, we felt that inclusion of these two journals was justified. Third, we used impact factor, which has been criticized as a marker of journal influence [23], due to its widespread recognition in academic medicine. It is possible that journals with lower impact factors not included in the study may have exhibited different trends. Fourth, results from this study included only the first 30 months of a 60-month period. A second analysis will be necessary to compare trends between these “early” and “late” publications. Lastly, we only included studies performed in LICs and LMICs, which may have biased our findings and excluded worthwhile studies of underrepresented populations in UMICs and HICs.

5. CONCLUSION

As the global scientific community makes concerted efforts to increase high-quality research in LIC and LMIC settings, it is essential to understand the subject areas of this research, where it is being conducted, and who is receiving the credit for conducting it. Without this knowledge, the global health movement runs the risk of inadvertently promoting the same type of overgeneralization and disproportional representation that researchers in this field aim to address. The trends identified in this study may help to inform the evolution and prioritization of future research efforts, thereby allowing global health to remain truly global.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Hugo Ahlenius of Nordpil (https://nordpil.com) for creating the cartograms.

Footnotes

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ACP (Alfred C. Papali), upon any request.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AP conceived the study idea and wrote the initial draft. MG and RH performed the literature review and data collection. ACV and MTM reviewed and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final draft.

FUNDING

This article received no external funding. Intramural funding from the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Maryland was provided for cartography.

REFERENCES

- [1].Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373:1993–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, Cairns CB, Harrington RA, Califf RM, et al. Ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:816–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0803929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Falagas ME, Alexiou VG. An analysis of trends in globalisation of origin of research published in major general medical journals. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:71–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Halpenny D, Burke J, McNeill G, Snow A, Torreggiani WC. Geographic origin of publications in radiological journals as a function of GDP and percentage of GDP spent on research. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:768–71. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hohmann E, Glatt V, Tetsworth K. Worldwide orthopaedic research activity 2010-2014: publication rates in the top 15 orthopaedic journals related to population size and gross domestic product. World J Orthop. 2017;8:514–23. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i6.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Evans JA, Shim JM, Ioannidis JP. Attention to local health burden and the global disparity of health research. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090147. e90147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kelaher M, Ng L, Knight K, Rahadi A. Equity in global health research in the new millennium: trends in first-authorship for randomized controlled trials among low- and middle-income country researchers 1990-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:2174–83. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chersich MF, Blaauw D, Dumbaugh M, Penn-Kekana L, Dhana A, Thwala S, et al. Local and foreign authorship of maternal health interventional research in low- and middle-income countries: systematic mapping of publications 2000-2012. Global Health. 2016;12:35. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0172-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].The World Bank Country and Lending Groups Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups (accessed October 12, 2014).

- [11].World Health Organization WHO Regional offices. Available at: http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/ (accessed September 3, 2014).

- [12].Macfarlane SB, Jacobs M, Kaaya EE. In the name of global health: trends in academic institutions. J Public Health Policy. 2008;29:383–401. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pauyo T, Debas HT, Kyamanywa P, Kushner AL, Jani PG, Lavy C, et al. Systematic review of surgical literature from resource-limited countries: developing strategies for success. World J Surg. 2015;39:2173–81. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rohwer A, Young T, Wager E, Garner P. Authorship, plagiarism and conflict of interest: views and practices from low/middle-income country health researchers. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018467. e018467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chaccour J. Authorship trends in The Lancet Global Health: only the tip of the iceberg? Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e497. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Elobu AE, Kintu A, Galukande M, Kaggwa S, Mijjumbi C, Tindimwebwa J, et al. Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery. 2014;155:585–92. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hedt-Gauthier BL, Riviello R, Nkurunziza T, Kateera F. Growing research in global surgery with an eye towards equity. Br J Surg. 2019;106:e151–e5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mugabo L, Rouleau D, Odhiambo J, Nisingizwe MP, Amoroso C, Barebwanuwe P, et al. Approaches and impact of non-academic research capacity strengthening training models in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:30. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reidpath DD, Allotey P. The problem of ‘trickle-down science’ from the Global North to the Global South. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001719. e001719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Riley L, Guthold R, Cowan M, Savin S, Bhatti L, Armstrong T, et al. The World Health Organization STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk-factor surveillance: methods, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:74–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hirshon JM, Risko N, Calvello EJ, Stewart de Ramirez S, Narayan M, Theodosis C, et al. Health systems and services: the role of acute care. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:386–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.112664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moresky RT, Razzak J, Reynolds T, Wallis LA, Wachira BW, Nyirenda M, et al. Advancing research on emergency care systems in low-income and middle-income countries: ensuring high-quality care delivery systems. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001265. e001265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Seglen PO. Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. BMJ. 1997;314:498–502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7079.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]