Significance

CENP-A, the histone H3 variant that forms a unique centromeric chromatin, is essential for faithful chromosome segregation during mitosis. Inability to connect the centromere to the mitotic spindle causes aneuploidy, a hallmark of many cancers. In addition to chromosome missegregation, chromosome fusions at (peri)centromeres are prevalent in cancers, but how such rearrangements arise remains unclear. Here, we identified a role for CENP-A in maintaining the integrity of centromere-associated repetitive sequences by ensuring their effective replication in human cells. In the absence of CENP-A, generation of DNA–RNA hybrids due to transcription–replication conflicts causes delayed DNA replication, centromere breakage, recombination, and chromosome translocations at centromeres. Centromeres thus possess a special mechanism to facilitate their replication and suppress chromosome translocations.

Keywords: CENP-A chromatin, DNA replication stress, chromosome translocations, genome instability, centromere

Abstract

Chromosome segregation relies on centromeres, yet their repetitive DNA is often prone to aberrant rearrangements under pathological conditions. Factors that maintain centromere integrity to prevent centromere-associated chromosome translocations are unknown. Here, we demonstrate the importance of the centromere-specific histone H3 variant CENP-A in safeguarding DNA replication of alpha-satellite repeats to prevent structural aneuploidy. Rapid removal of CENP-A in S phase, but not other cell-cycle stages, caused accumulation of R loops with increased centromeric transcripts, and interfered with replication fork progression. Replication without CENP-A causes recombination at alpha-satellites in an R loop-dependent manner, unfinished replication, and anaphase bridges. In turn, chromosome breakage and translocations arise specifically at centromeric regions. Our findings provide insights into how specialized centromeric chromatin maintains the integrity of transcribed noncoding repetitive DNA during S phase.

Centromeres hold a paradox: Their essential function to support accurate chromosome segregation is evolutionarily conserved yet their DNA sequence is rapidly evolving (1–3). Human centromeres span ∼0.3 to 5 Mb with repetitive alpha-satellite DNA arranged in tandem and then reiterated as homogeneous higher-order repeat (HOR) blocks (4). Evolution of centromere repeats has been modeled by short- and long-range recombination events such as gene conversion, break-induced replication, crossing-over, and other mutagenic processes (2, 3, 5, 6). Changes in centromere size may contribute to meiotic drive (2), but may also elicit genome instability (7) by increasing the rate of chromosome missegregation (8). While recombination at centromeres is suppressed in meiosis (9), it is present in somatic cells and enhanced in cancerous cells (10) where whole-arm chromosome translocations are prevalent (11, 12). The mechanism(s) that prevents breakage and translocations at these highly repetitive centromere sequences remains elusive.

Human centromeres are epigenetically specified by the histone H3 variant CENP-A (13, 14), which acts as a locus-specifying seed to assemble kinetochores for mitotic functions (15). While pericentromeric regions form heterochromatin, the core centromere harbors euchromatic characteristics with active transcription throughout the cell cycle, where long noncoding RNAs act in cis to contribute to centromere functions (16, 17). To date, it is unknown how 1) transcription (17), 2) recombination (10), 3) late replication (18, 19), and 4) propensity to form non–B-DNA and secondary structures (20–22), all features commonly associated with human fragile sites (23), are regulated to maintain the integrity of centromeric repeats. Here we identified a critical role for CENP-A in the maintenance of centromeric DNA repeats by repressing R-loop formation during DNA replication, thereby avoiding DNA replication stress and suppressing abortive chromosome translocation at the centromeres.

Results

We previously demonstrated that long-term CENP-A loss promotes alpha-satellite recombination events (10), suggesting a potential role for CENP-A in the maintenance of the integrity of centromere repeats, beyond its role in kinetochore formation and spindle stability (14, 24). As telomeres and ribosomal DNA (rDNA) possess specialized mechanisms that prevent their repetitive sequences from instability in S phase (25, 26), we hypothesized that CENP-A plays a role in suppressing alpha-satellite fragility during DNA replication. To test this, we used a system that allows rapid removal of endogenous CENP-A–containing nucleosomes using an auxin-inducible degron (AID) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) in human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT)-immortalized, nontransformed, diploid retinal pigment epithelial (RPE-1) cells (27). We first monitored the consequences of CENP-A removal for nucleosome stability using stably expressed SNAP-tagged H4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), a modified version of the suicide enzyme O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. In untreated RPE-1 cells, when SNAP-H4 is labeled with tetramethylrhodamine in G1, the majority of signals accumulate at centromeres (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C), as previously reported (28). This is likely caused by the fact that CENP-A nucleosomes assemble during late M/early G1 (29), whereas canonical nucleosome assembly is coupled to DNA replication. Since SNAP-tagged H4 transgene expression is not cell cycle-regulated while endogenous H4 levels peak in S phase, this favors incorporation together with CENP-A at centromeric nucleosomes in G1. Auxin (indole-3-acetic acid; IAA) addition led to the disassembly of CENP-A–containing nucleosomes as shown by rapid loss of CENP-A and of previously incorporated SNAP-tagged H4 selectively at centromeres but not globally at bulk chromatin (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B–E). However, new incorporation of H4 at centromeres at any phases of the cell cycle was not altered by CENP-A removal in G1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 F and G), as assessed by H4SNAP quenching/release and H4K5Ac CUT&RUN-qPCR (30). Considering that human centromere segments are occupied mostly by H3 nucleosomes with ∼200 interspersed CENP-A nucleosomes (31), we expect the impact of short-term CENP-A depletion on the physical property of centromeric chromatin to be minimal.

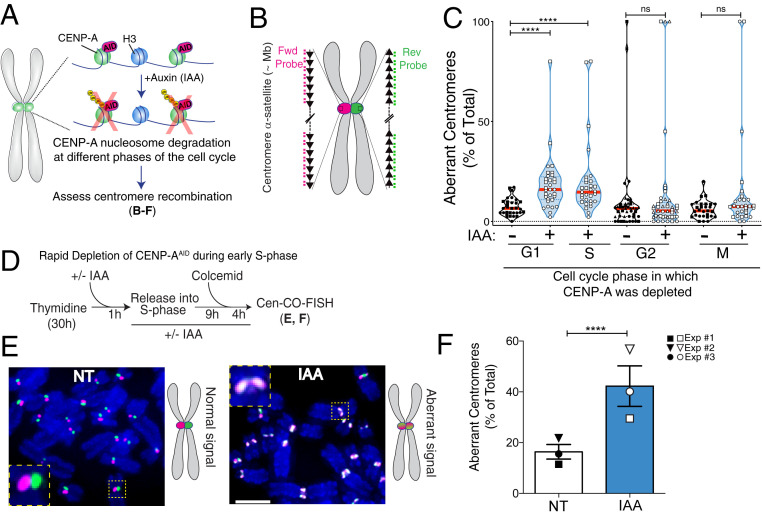

Fig. 1.

Rapid removal of CENP-A during S phase increases centromere recombination. (A) Schematic of the inducible degradation system to deplete endogenous CENP-A after addition of auxin (IAA) in RPE-1 cells. (B) Schematic illustration of the Cen-CO-FISH centromeric DNA probes. Hybridization by unidirectional peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes differentially labels the forward or reverse strands of each sister chromatid. Each black arrow symbolizes a HOR in the alpha-satellite array. (C) Quantification of the percentage of aberrant Cen-CO-FISH patterns per cell with or without CENP-A depletion in the different phases of the cell cycle as indicated. For synchronization strategy, see SI Appendix, Fig. S1 H and I. Cells from two or three independent experiments are depicted with a different shape with n = 15 cells per condition and per experiment. Red lines represent the median. A Mann–Whitney U test was performed on the pooled single-cell data of two or three independent experiments: ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. (D) Synchronization strategy for the Cen-CO-FISH experiment shown in E and F. (E, Left) Representative Cen-CO-FISH on metaphase chromosomes after CENP-A depletion in the previous S phase. (E, Right) Schematic of the resulting Cen-CO-FISH staining patterns in normal and abnormal centromeres, with visible sister chromatid exchange (SCE) due to recombination and cross-over events. (Scale bar, 5 µm.) (F) Quantification of the percentage of aberrant Cen-CO-FISH patterns per cell in non-treated cells (NT) and after CENP-A depletion (IAA) in the previous S phase. The bar graph is the average of three independent experiments (depicted with different shapes) with n = 15 cells per condition. The bars represent the SEM. A Mann–Whitney U test was performed on pooled single-cell data of three independent experiments: ****P < 0.0001.

To establish the critical time when CENP-A disruption causes alpha-satellite instability, we induced CENP-A depletion at different stages of the cell cycle (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 H and I) and monitored recombination at centromeres in the first mitosis using centromeric chromosome-orientation fluorescence in situ hybridization (hereafter referred to as Cen-CO-FISH; Fig. 1B) (32). CENP-A depletion upon release from G1 arrest (by the CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib), 8 h after G1 release corresponding to S-phase entry, or release from early S-phase arrest (by thymidine block), but not in G2- or metaphase-arrested cells, triggered severe centromere rearrangements (Fig. 1 C–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1J). These data indicate that absence of CENP-A in S phase increases recombination at centromeres. We noticed that CENP-A depletion upon release from the early S-phase arrest by thymidine caused more robust aberrations in the Cen-CO-FISH pattern than CENP-A depletion upon G1 arrest by Palbociclib. This suggests that centromere integrity is sensitive to preinduced DNA replication stress and further enhanced by CENP-A depletion.

Since DNA replication stress can induce recombination, we assessed if replication fork dynamics were altered by CENP-A depletion using DNA combing for single-molecule analysis (33). We performed sequential labeling of nascent DNA with nucleotide analogs, chlorodeoxyuridine (CldU) and iododeoxyuridine (IdU) (Fig. 2A), during early S (3 h) when mostly euchromatin is replicated (34), and in late S (7 h) when centromeres are replicated (18, 19) as confirmed by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) immunoprecipitation (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). A change in CldU + IdU track length was used as an indicator of a change in replication fork progression. Removal of CENP-A did not alter replication fork speed 3 h after thymidine release (Fig. 2 B and C). However, at 7 h, when fork speed accelerated in untreated cells as previously observed (35), fork speed was reduced upon CENP-A depletion (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). These phenotypes were not due to perturbations in cell-cycle progression, as CENP-A–depleted cells entered and progressed through S phase with the same kinetics as untreated cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E).

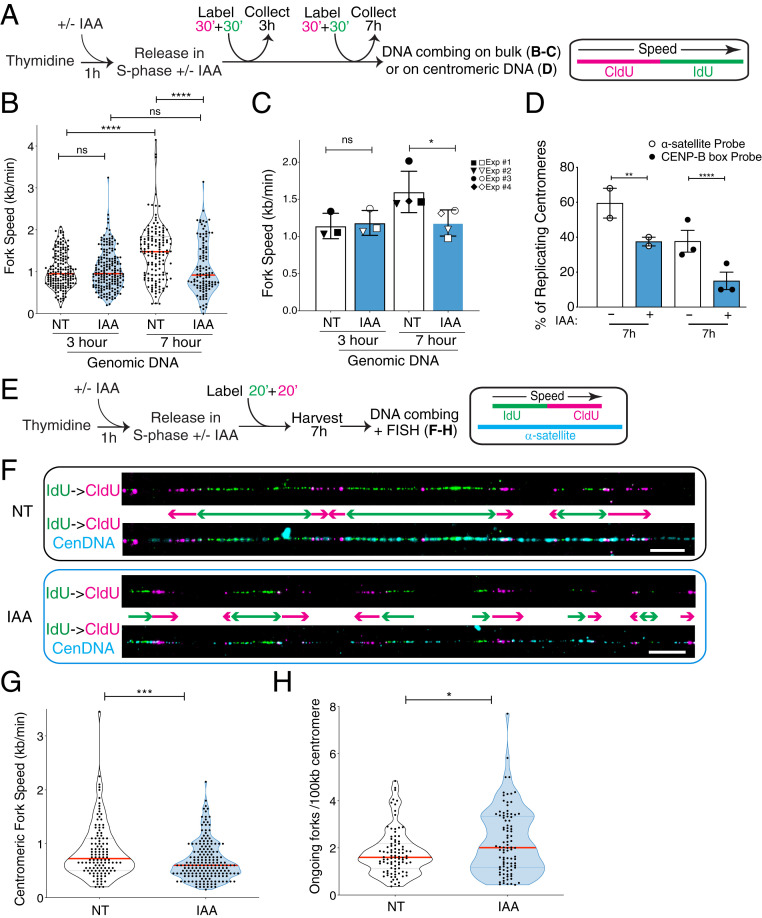

Fig. 2.

CENP-A removal leads to impaired replication fork progression through centromere alpha-satellites in late S phase. (A) Schematic illustration of the single-molecule DNA replication experiments shown in B–D. (B) Quantification of the replication fork speed in n > 100 tracks per condition. The red bars represent the median. Mann–Whitney U test: ****P < 0.0001. (C) Summary of the quantification of the replication fork speed in the bulk genome at 3 or 7 h after thymidine release in three or four independent experimental replicates represented by different symbols. The bars represent the SD of the mean. Mann–Whitney U test: *P = 0.0286. (D) Quantification of the percentage of actively replicating centromeres in the DNA combing assay (IdU- and/or CldU-positive). Two different oligo PNA probes were used to target alpha-satellites. Each dot represents one experiment with n > 30 centromeric tracks per condition. The bars represent the SEM. χ2 test: **P = 0.005, ****P < 0.0001. (E) Schematic illustration of the single-molecule DNA replication experiments at the centromeric regions shown in F–H, where six RNA probes were used to target alpha-satellites. (F) Representative images of single-molecule alpha-satellite DNA combing at 7 h after thymidine release. A probe mix recognizing alpha-satellite repeats was used to specifically label centromeres. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) (G) Quantification of the centromeric replication fork speed at 7 h after thymidine release. n > 110 tracks per condition. The lines represent the median with interquartile range. Mann–Whitney U test: ***P = 0.0006. (H) Quantification of the number of ongoing forks per 100 kb at centromeres at 7 h after thymidine release. n > 90 tracks per condition. The lines represent the median with interquartile range. Mann–Whitney U test: *P = 0.0411.

To directly assess replication fork dynamics at centromeric repetitive DNA, alpha-satellites were labeled by two different FISH probes on combed DNA. Among these FISH-positive segments of fibers ranging from 50 to 200 kb, the overall frequency of IdU- and/or CldU-labeled fibers at 7 h from thymidine release was reduced upon CENP-A depletion (Fig. 2D), suggesting that replication at alpha-satellite repeats was impaired. To cover longer and more diverse stretches of alpha-satellites, we used a mix of six different ∼50-bp probes that hybridize to alpha-satellite DNA ranging from 50 to 1,300 kb (median of ∼250 kb) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). This analysis revealed that replication of centromeric DNA occurs in clusters (Fig. 2 E and F), leading to many converging forks at 7 h after thymidine release. As termination promotes topological burdens (36), this could contribute to slower replication at centromeres compared with the bulk genome (37). In CENP-A–depleted cells, replication fork speed at fibers labeled with the probe mix was reduced compared with untreated conditions (median 0.72 to 0.60 kb/min) (Fig. 2G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2G). Within replication clusters seen in late S phase at centromeres (Fig. 2F), we observed an increase in the number of ongoing forks per 100 kb (median 1.60 vs. 2.01) upon CENP-A depletion (Fig. 2H), indicating dormant origin firing, possibly reflecting compensation for the diminished fork velocity. However, dormant origin firing was not sufficient to fully rescue timely replication of entire segments of centromeres in late S phase (Fig. 2 D and F). Altogether, our data suggest that CENP-A is needed for efficient replication fork progression through alpha-satellite repeats.

As a candidate for the impediments that induce replicative stress at centromeres upon CENP-A depletion, we monitored the occurrence of DNA–RNA hybrids (R loops), known to obstruct DNA replication fork progression (Fig. 3A) (38). To detect R loops at centromeres, we used DNA–RNA immunoprecipitation (DRIP) analysis, which captures DNA–RNA hybrids in their native chromosomal context (39), followed by qPCR amplification of centromere X-specific alpha-satellites (Fig. 3B) or pan-centromeric alpha-satellites (Fig. 3C). We found a modest but reproducible increase of centromere-associated R loops upon CENP-A removal particularly in late S phase (Fig. 3 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), the time when most centromeres are replicated (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The signals were specific to DNA–RNA hybrids, since they were not detectable with the control immunoglobulin (IgG), and were eliminated by treatment with RNase H1 (Fig. 3C). DNA–RNA hybrids were induced upon IAA treatment at centromeres, but not within the hybrid-rich β-actin terminator (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Induction of centromere-associated DNA–RNA hybrids upon acute CENP-A depletion during thymidine release was also confirmed using immunofluorescence-based detection of the S9.6 antibody (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B–D), where such induction at centromeres is only seen in late S phase and absent when CENP-A is depleted during G2 or M phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Taken together, these data show that CENP-A depletion causes impaired DNA replication progression and R-loop formation at centromeres.

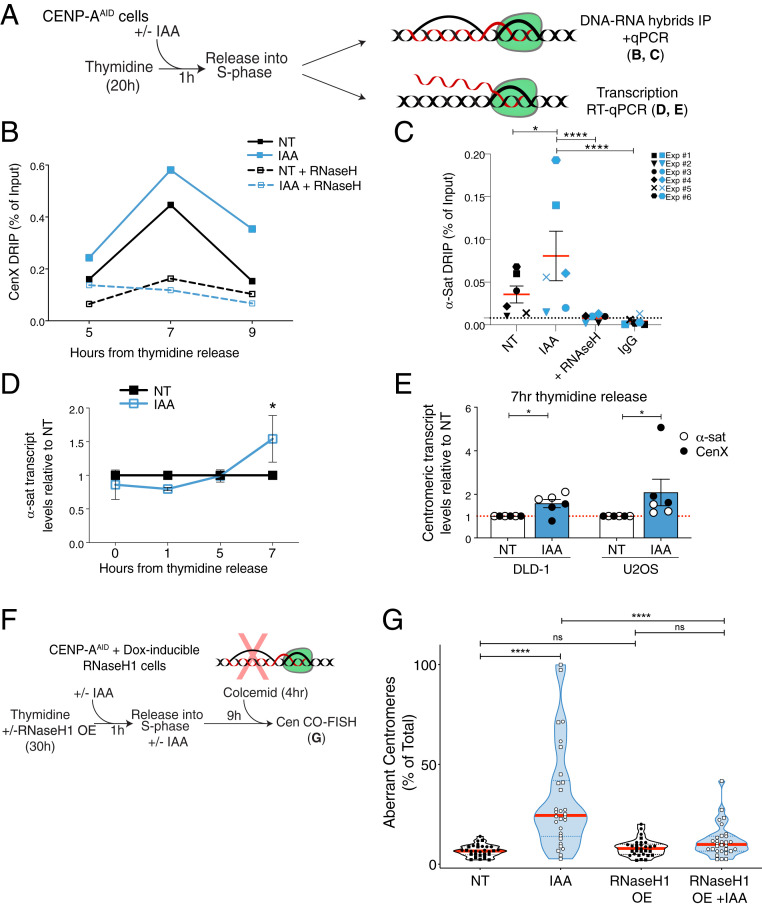

Fig. 3.

Accumulation of R loops following CENP-A depletion causes increased centromere recombination. (A) Schematic illustration of the experiments shown in B–E. (B) DRIP-qPCR quantification of the R-loop levels at the centromere of chromosome X as a measure of the percentage of input retrieved at different time points in S phase. n = 1. Each dot shows the mean of technical replicates. (C) DRIP-qPCR of R-loop levels at the centromeres as a measure of the percentage of input retrieved using alpha-satellite primers at 7 h after thymidine release. Each dot shows the mean of three technical replicates of six independent experiments represented by different symbols. A t test was performed including the technical replicates. *P = 0.019, ****P < 0.0001. (D) Quantification of centromere transcript levels using alpha-satellite primers by qRT-PCR after thymidine release. IAA data were normalized over the corresponding NT. Each dot represents the mean of two to eight independent experiments. The bars represent the SEM. One-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test: *P = 0.0312. (E) Quantification of the transcript levels at the centromeres using alpha-satellite and Cen X primers and by qRT-PCR 7 h after thymidine release in DLD-1 and U2OS cells. IAA data were normalized over the corresponding NT. Each dot represents the mean of three technical replicates. The bars represent the SEM. U2OS cells: one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test: *P = 0.0312. DLD-1 cells: one-sample t test: *P = 0.0273. (F) Schematic illustration of the rescue experiment shown in G. (G) Quantification of the percentage of aberrant Cen-CO-FISH patterns per cell after RNase H1 overexpression (OE), and subsequent CENP-A depletion during the prior S phase. Cells from two independent experiments are depicted with a different shape with n = 15 cells per condition and per experiment. The red lines represent the median. A Mann–Whitney U test was performed on the pooled single-cell data of the two independent experiments: ****P < 0.0001.

R loops, which form cotranscriptionally, are prevalent at replication–transcription conflicts (38, 40). Centromeres are actively transcribed throughout the cell cycle (17, 41), raising the hypothesis that CENP-A depletion causes R-loop formation due to convergence of replication and transcription machineries. Upon release from thymidine-mediated arrest, CENP-A depletion did not affect the levels of centromere transcripts during early S phase, but when cells progressed to late S phase, the RNA levels increased (Fig. 3 A and D). This increase was reproducible using different centromeric probes and in two other cell lines, U2OS and DLD-1 (Fig. 3E). We also confirmed that de novo centromere transcription is indeed active in late S phase by immunoprecipitation followed by qRT-PCR of 5-fluorouridine (FU) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 E–G). Finally, while the large majority of active RNA polymerase II dissociates from mitotic chromosomes (42, 43), an increase in centromere-associated active polymerase after CENP-A depletion was detected during mitosis (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 H and I). This increase was concomitant with the accumulation of the DNA damage kinase ATR (21), consistent with persistent stress at centromeric regions, but with no detectable increase in R loops (SI Appendix, Fig. S3I).

Consistent with the notion that R loops derive from transcription–replication conflicts (44), levels of γH2AX at centromeres increased in late S phase after CENP-A depletion (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C), with γH2AX foci occupying a region within and at the periphery of the centromere (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B), perhaps reflecting previously reported peripheral replication of centromeres (45). To test if R loops could cause centromere damage and alpha-satellite repeat instability, we stably integrated RNase H1 under a doxycycline-inducible promoter in the hTERT-RPE-1 EYFP-AIDCENP-A cell line (Fig. 3F) (21). Expression of RNase H1 was able to rescue phenotypes observed in CENP-A–depleted cells such as enhanced centromere-associated γH2AX (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C) and aberrant Cen-CO-FISH patterns indicative of centromere recombination (Fig. 3G). Similar results were obtained by targeting RNase H1 to the alpha-satellite repeats via the inducible expression of the RNase H1 fused to the CENP-B DNA-binding domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 D–F). These data demonstrate that the centromere instability in the absence of CENP-A is caused by the generation of centromeric R loops during alpha-satellite DNA synthesis.

Replicative stress is a main driver of genome instability (46, 47). It has been shown that persistent replication intermediates in mitosis are processed via the error-prone mitotic DNA synthesis (MiDAS), prominently observed at common fragile sites (CFSs) (48). To test if the replication stress imposed by CENP-A depletion in S phase results in MiDAS, we depleted CENP-A in asynchronous cell culture for 10 h and monitored incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) during the subsequent first mitosis (Fig. 4A), assuming that these mitotic cells had gone through S phase without CENP-A. We noticed an increase in cells containing EdU foci following CENP-A depletion, to a similar level of the DNA replication slowdown induced with a low dose of aphidicolin (48) (Fig. 4B). The EdU foci in the IAA-treated sample were found to be enriched at centromeric regions with the proximity ligation assay (PLA), which was not observed with aphidicolin treatment only (Fig. 4C). This suggests that removal of CENP-A causes a subset of centromeres to continue replication into mitosis.

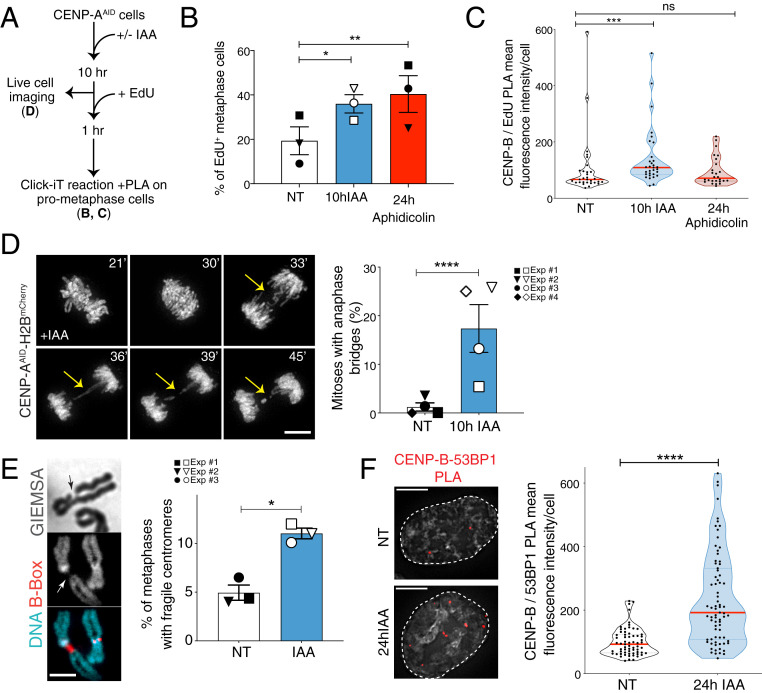

Fig. 4.

CENP-A removal in S phase causes centromere fragility in mitosis. (A) Schematic illustration of the experiments shown in B and C. (B) Quantification of the percentage of EdU-positive metaphases after 10 h IAA or 24 h aphidicolin (0.2 μM). Each dot represents one experiment. The bars represent the SEM. χ2 test: *P = 0.0435, **P = 0.0044. (C) Quantification of EdU-positive centromeres in metaphase cells by measuring mean fluorescence intensity signal from PLA between CENP-B and EdU-biotin after 10 h IAA or 24 h aphidicolin (0.2 μM). n > 25 cells per condition. The lines represent the median with interquartile range. Mann–Whitney U test: ***P = 0.0009. (D, Left) Representative still images of H2B-mCherry RPE-1 live-cell imaging showing the presence of an anaphase bridge (yellow arrows) after 10 h IAA. (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (D, Right) Quantification of the percentage of RPE-1 cells showing at least one anaphase bridge after 10 h IAA. Each dot represents one of four independent experiments depicted by different symbols. The bars represent the SEM. χ2 test: ****P < 0.0001. (E, Left) Representative FISH images of a chromosome with reduced DAPI/Giemsa staining at the centromere, identified with a CENP-B box FISH probe. (E, Right) Quantification of the percentage of metaphase spreads showing reduced DAPI/Giemsa staining at the centromere after 24 h IAA (square) or after thymidine release (circle and inverted triangle). Each dot represents one experiment with n > 70 cells. The bars represent the SEM. χ2 test: *P = 0.0113. (Scale bar, 3 µm.) (F, Left) Representative immunofluorescence images of PLA between CENP-B and 53BP1. (F, Right) Quantification of centromeric DNA damage in RPE-1 cells by measuring PLA mean fluorescence intensity signal between CENP-B and 53BP1 after 24 h IAA. n > 65 cells per condition. The bars represent the SEM. Mann–Whitney U test: ****P < 0.0001. (Scale bars, 5 µm.)

Mitotic entry with underreplicated or unresolved recombination intermediates causes anaphase bridges (49). To monitor if replication stress induced by CENP-A depletion generates such mitotic perturbations, we used live-cell imaging to follow chromosome separation in RPE-1 cells. CENP-A depletion in G1/early S (Fig. 4A) indeed increased the frequency of chromosome bridges threaded between the segregating DNA masses (Fig. 4D and Movie S1). In contrast, the number of ultrafine bridges (UFBs) marked with the Plk1-interacting checkpoint helicase (PICH), often seen at centromeres (50), was not affected by CENP-A depletion (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), implying different underlying molecular origins (51, 52) and substantiating that most centromeric UFBs are not originating from underreplication but instead through DNA decatenation impairment (53). Moreover, we detected a significant increase in regions with no or reduced DAPI/Giemsa staining—possibly due to chromosome breakage or underreplicated or decondensed regions—affecting specifically one or more metaphase centromeres (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B) and resembling cytological abnormalities seen at CFSs after replicative stress. We also found colocalization between the DNA double-strand break factor 53BP1 and the centromeric sequence-specific DNA-binding protein CENP-B by PLA in the following cell cycle after CENP-A depletion (Fig. 4F), suggesting that DNA breaks persist at the centromere in interphase. In summary, our data show that upon entry into mitosis, replication impairments caused by CENP-A depletion lead to centromere instability, therefore mimicking fragile sites and underreplicated regions of the genome.

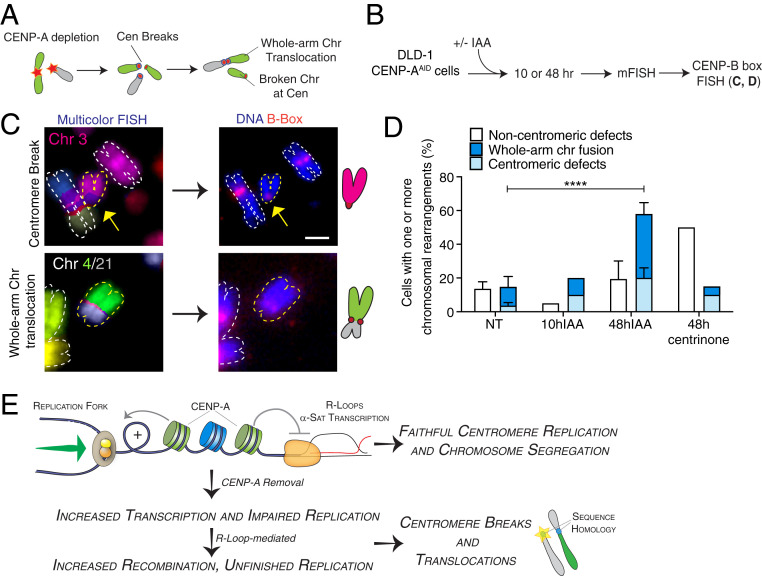

DNA damage at centromere segments may induce chromosome translocations between chromosomes with homologous centromere sequences (Fig. 5A). To score them, we combined multicolor FISH (mFISH) followed by CENP-B box FISH staining to check the status of centromeric DNA (Fig. 5B). Within two cell cycles following CENP-A depletion, centromeric abnormalities and rearrangements were induced at one or more chromosomes, beyond numerical aneuploidy. These abnormalities spanned centromere breakage and fragmentation, isochromosomes, and a high proportion of whole-arm chromosome translocations involving both acrocentric and metacentric chromosomes (Fig. 5 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C–E). No chromosomal translocations were detected in cells arrested in the first mitosis without CENP-A (10 h IAA) (Fig. 5D), indicating that anaphase bridge breakage is likely a necessary step for centromere instability to trigger overall genome instability, as recently shown for the mitotic chromosome breakage–fusion–bridge cycle (54). To ensure that this phenotype was not due to whole-chromosome missegregation resulting from CENP-A depletion (27), we generated mitotic defects independent of centromeric dysfunction by centrosome depletion with a Plk4 inhibitor (48 h centrinone) (55). In this case, we still detected an increase in chromosomal rearrangements, but such alterations occurred mainly outside the centromeric regions (e.g., telomere fusions; Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 C and D), confirming the specific effect of CENP-A depletion on centromere DNA fragility and chromosome integrity. These results imply that chromosome translocations at centromeres are not the primary consequence of chromosome missegregation but are generated by mitotic DNA breakages due to replication stress at centromeres.

Fig. 5.

Centromere instability caused by CENP-A depletion during DNA replication initiates chromosome rearrangements and translocations in the ensuing cell cycles. (A) Illustration of the formation of centromeric chromosomal rearrangements after CENP-A depletion due to breaks generated during the previous cell cycle and repaired by nonallelic homologous recombination. (B) Schematic representation of the multicolor-FISH experiments shown in C and D. (C) Representative images of mFISH and centromeric FISH (CENP-B box probe) of DLD-1 chromosome spreads showing chromosomal aberrations occurring at centromeres after 48 h IAA. Schematics of the observed events are also shown. (Scale bar, 2 µm.) (D) Quantification of the percentage of metaphase spreads showing chromosomal rearrangements by mFISH after CENP-A depletion or centrosome depletion in DLD-1 cells. n = 3 (NT and 48 h IAA) or 1 (10 h IAA and 48 h 0.2 μM centrinone). The bars represent the SEM. χ2 test: ****P < 0.0001. (E) Model for maintenance of centromeric DNA stability mediated by CENP-A–containing chromatin. See text for details.

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that CENP-A is critical in the maintenance of centromeric DNA repeats by repressing R-loop formation during DNA replication (Fig. 5E). While impaired histone assembly onto newly replicated DNA impedes replication (56), our CENP-A depletion did not interfere with histone assembly during S phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 F and G). Instead, CENP-A nucleosome removal on parental DNA slows replication fork progression at centromeres, likely due to replication–transcription conflicts, which stabilize R loops. Intriguingly, slowed DNA replication upon CENP-A depletion was observed at genomic levels during late S (Fig. 2 B and C), raising a possibility that CENP-A removal also perturbs replication of noncentromeric regions. This may be related to the observation that CENP-A accumulates outside centromeres (31) at DNA damage sites (57) or at transcriptionally active regions before being removed in a replication-dependent manner (58). However, the effect of CENP-A depletion on the replication slowdown is specific to late S phase—a time when centromeres are actively replicated (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A)—and, importantly, the subsequent increase in fragility and rearrangements were specifically found at centromeres (Fig. 5D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Together, our data highlight the role of CENP-A in S phase to prevent DNA instability at the centromeres.

While nucleosomes generally suppress transcriptional initiation (59) and compete with R-loop formation (40), CENP-A depletion increased R-loop and centromeric RNA levels only during centromere replication. Thus, we propose that CENP-A chromatin holds a specialized function to facilitate fork progression and suppress R-loop formation at centromeres during DNA replication. Since a subset of alpha-satellite RNAs stay associated with the centromere from which they were transcribed throughout the cell cycle (17), CENP-A chromatin may sequester these RNAs to minimize R-loop formation upon replication–transcription conflicts. This is consistent with a report that CENP-C and other centromeric proteins can bind to RNA (17), and depletion of constitutive centromere-associated network components (such as CENP-C, CENP-T, and CENP-W) induces aberrant centromere recombination without obvious displacement of CENP-A from chromatin (10). It is also possible that CENP-A is important for recruitment of proteins, such as helicases that remove DNA–RNA hybrids (38). Altogether, our results suggest that centromeric DNA regions are intrinsically difficult to replicate to a similar extent as other repetitive sequences where specialized proteins act to facilitate fork progression (60, 61).

Mitosis with underreplicated DNA and/or recombination caused by CENP-A depletion can lead to DNA damage in a subset of centromeres (Fig. 4), potentially promoting nonallelic exchanges between near-identical repeats on different chromosomes (Fig. 5) (7, 11). Only a small fraction of CENP-A–depleted centromeres undergo such instability, possibly due to low levels of transcription (17, 41), compensation by dormant origin firing (Fig. 2H), and MiDAS (Fig. 4 A–C), which minimize centromeric underreplication ahead of cell division. In addition to sequence homology, centromere clustering may facilitate chromosome translocation at centromeres (62). Notably, intercentromeric rearrangements following centromere instability increased preferentially in acrocentric chromosomes, which are frequently linked together at their rDNA loci forming the nucleoli (63). As CENP-A levels are reduced in senescent cells (64) and in certain types of organismal aging in humans (65), centromere-induced structural aneuploidy may represent a key mechanism underlying aging-associated tumorigenesis. Senescent cells present hypomethylated and highly transcribed centromeres (66, 67) that show altered nucleolar association (68), which in turn might impact the regulation of alpha-satellite expression (41) and favor rearrangements at acrocentric chromosomes. Finally, in agreement with a role of CENP-A in protecting centromeric regions, loss of CENP-A from the original alpha-satellite locus during neocentromere formation can be accompanied by erosion at the repeats (69). Our data point toward the possibility that the high prevalence of centromeric transcript overexpression and whole-arm chromosome translocations seen in cancer is caused by compromised functionalities of centromeric chromatin that suppress DNA replication stress (11, 12).

Methods

Cell Synchronization and Treatments.

In preparation for the experiment, hTERT RPE-1 cells were split at low confluency (∼3 × 105 cells per 10-cm dish) ∼24 h prior to treatment. Indole-3-acetic acid (auxin) (I5148; Sigma) was dissolved in double distilled water (ddH2O) and used at a final concentration of 500 μM. RNase H1-green fluorescent protein expression (GFP) was induced using 200 ng/μL of doxycycline. RNase H treatment on fixed cells was performed using 5 U RNase H (M0297; NEB) for 3 h at 37 °C, or mock for no RNase H digestion control in 1× RNase H digestion buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane [DTT]) without the enzyme, before proceeding to immunofluorescence. The thymidine synchronization and release experiment was performed by incubating cells with 2 to 5 mM thymidine for 22 to 28 h; cells were then treated with IAA for 1 h, washed three times with Dulbecco sterile phosphate-buffered saline, and released into fresh medium containing IAA. For G1 synchronization, cells were treated for 24 h with 150 nM Palbociclib (S1116; Selleck), a CDK4/6 inhibitor, before washing out and releasing from the arrest (70). G2 arrest was induced by the RO-3306 CDK1 inhibitor (ALX-270-463; Enzo) at 10 μM final concentration for 20 h. Mitotic arrest was achieved using 0.1 μg/mL colcemid (Roche) for 5 h, followed by mitotic shakeoff to obtain a pure mitotic population for processing. Centrinone (Clinisciences; HY-18682) treatment to induce centrosome loss was performed at 0.2 μM for 48 h.

Cen-CO-FISH.

CO-FISH at centromeres was performed as previously described (32). A detailed protocol is available in SI Appendix, Methods.

Microscopy, Live-Cell Microscopy, and Image Analyses.

Images were acquired on a fluorescence microscope DeltaVision Core System (Applied Precision) with a 100× Olympus UPlanSApo 100 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.4), 250-W xenon light source equipped with a Photometrics CoolSNAP_HQ2 camera; ∼4-µm Z stacks were acquired (Z-step size: 0.2 µm). Imaris software (Bitplane) was used to quantify fluorescence intensity in the deconvolved three-dimensional images using centromere surfaces automatically determined by anti-centromere antibodies (ACA) staining detection. Quantification of γH2AX and S9.6 R loops at centromeres was performed using the Imaris software (Bitplane) surface fitting function and extracting mean fluorescence intensity for each centromere. All images presented were imported and processed in Photoshop (Adobe Systems). Movies of live cells were acquired using an inverted Eclipse Ti-2 (Nikon) full motorized + spinning disk CSU-W1 (Yokogawa) microscope. Cells were grown on high–optical-quality plastic slides (ibidi) for this purpose.

Multicolor-FISH Karyotyping.

Cells grown to ∼75 to 80% confluency were treated with colcemid (0.1 μg/mL) for 3 h and prepared as previously described (8) for mFISH karyotyping. The Metafer imaging platform (MetaSystems) and Isis software were used for automated acquisition of the chromosome spread and mFISH image analysis.

CUT&RUN-qPCR.

CUT&RUN was performed according to the procedure previously reported (71) starting from 1 million cells and using an anti-H4K5Ac (Abcam; ab51997; 1/1,000) antibody. A rabbit IgG isotype control antibody (Thermo Fisher; 10500C; 1/100) was used for background detection. qPCR was performed using the LightCycler 480 System (Roche) with the primers reported in SI Appendix. Fold enrichment at centromeres was calculated using alpha-satellite primers, with the ΔΔCt method. The rabbit IgG isotype sample was used as the control sample and normalization was performed to the Ct values from the Alu repeat primers.

Statistical Testing.

Statistical analysis of all the graphs was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. A two-sided χ2 test was performed on categorical datasets. t tests and Mann–Whitney U tests were respectively performed on quantitative datasets depending on whether they followed a normal distribution or not. When data from the untreated samples were normalized to 1, a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test or a one-sample t test was performed and compared with a theoretical value of 1.

Additional Methods.

Detailed descriptions of the following materials and methods can be found in SI Appendix, Methods: cell culture, fluorescence in situ hybridization, Cen-CO-FISH, DNA combing, chromatin extraction and immunoblotting, histone deposition monitoring with SNAP labeling, generation of stable cell lines, flow cytometry, EdU staining in metaphase cells, immunofluorescence, proximity ligation assay, antibodies, ultrafine bridge immunofluorescence staining, metaphase spread centromere quantification, unfixed chromosome spreads, BrdU immunoprecipitation for nascent DNA, DNA–RNA hybrid immunoprecipitation, FU immunoprecipitation for nascent RNA, qRT-PCR, and qPCR primers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mathieu Maurin (Institut Curie) for helping with image analysis; Titia de Lange, Kaori Takai, Francisca Lottersberger, Nazario Bosco, and other members of the de Lange laboratory (The Rockefeller University) for helpful assistance with the CO-FISH technique; Iain Hagan and Wendy Trotter (University of Manchester) for sharing synchronization information for Palbociclib; Florence Larminat (Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale), Kok-Lung Chan (Sussex University), Simon Gemble (Institut Curie), and Whitney Johnson (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) for suggestions on DRIP, UFBs, and centromeric qRT-PCR, respectively; Hai Dong Nguyen and Lee Zou (Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center), Brooke Conti (The Rockefeller University), Lars Jansen (Oxford University), Renata Basto (Institut Curie), and Kavitha Sarma (The Wistar Institute) for sharing reagents; Jennifer Gerton, Karen Miga, Tatsuo Fukagawa, and Tetsuya Hori for sharing unpublished data; and Arturo Londoño-Vallejo, Claire Francastel, Graça Raposo, Ines Drinnenberg, and Aaron Straight for fruitful discussions and support. We also thank the Flow Cytometry platform, Cell and Tissue Imaging facility (PICT-IBiSA, a member of French National Research Infrastructure France-BioImaging ANR10-INBS-04), the Antibody facility platform, the Recombinant Protein Production platform, and the Sequencing platform at the Institut Curie, and the Bio-Imaging Resource Center and Flow Cytometry Resource Center at The Rockefeller University. D.F. receives salary support from the CNRS. D.F. has received support for this project from Labex “CelTisPhyBio,” the Institut Curie, the ATIP-Avenir 2015 Program, the program “Investissements d’Avenir” launched by the French Government and implemented by Agence Nationale de la Recherche with the references ANR-17-CE12-0003, ANR-10-LABX-0038, and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL, Emergence Grant 2018 from the City of Paris. S.H. received funding from Paris Sciences & Lettres (PSL) and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC) Foundation. H.F. was supported by grants from the NIH (R35 GM132111 and R01 GM121062). G.R. was supported by National Research Foundation Investigatorship NRF-NRFI05-2019-0008. R.R.W. was supported by a Merck Postdoctoral Fellowship Award and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Research Service Award Fellowship 5F32DK115144. A. Smogorzewska is a Faculty Scholar of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2015634118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Fukagawa T., Centromere DNA, proteins and kinetochore assembly in vertebrate cells. Chromosome Res. 12, 557–567 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henikoff S., Ahmad K., Malik H. S., The centromere paradox: Stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 293, 1098–1102 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbert P. B., Henikoff S., Centromeres convert but don’t cross. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000326 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schueler M. G., Higgins A. W., Rudd M. K., Gustashaw K., Willard H. F., Genomic and genetic definition of a functional human centromere. Science 294, 109–115 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice W. R., A game of thrones at human centromeres II. A new molecular/evolutionary model. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2020). 10.1101/731471. Accessed 18 February 2021. [DOI]

- 6.Smith G. P., Evolution of repeated DNA sequences by unequal crossover. Science 191, 528–535 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black E. M., Giunta S., Repetitive fragile sites: Centromere satellite DNA as a source of genome instability in human diseases. Genes 9, 615 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumont M., et al., Human chromosome-specific aneuploidy is influenced by DNA-dependent centromeric features. EMBO J. 39, e102924 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nambiar M., Smith G. R., Repression of harmful meiotic recombination in centromeric regions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 54, 188–197 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giunta S., Funabiki H., Integrity of the human centromere DNA repeats is protected by CENP-A, CENP-C, and CENP-T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1928–1933 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barra V., Fachinetti D., The dark side of centromeres: Types, causes and consequences of structural abnormalities implicating centromeric DNA. Nat. Commun. 9, 4340 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beroukhim R., et al., The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 463, 899–905 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fachinetti D., et al., A two-step mechanism for epigenetic specification of centromere identity and function. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1056–1066 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKinley K. L., Cheeseman I. M., The molecular basis for centromere identity and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 16–29 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santaguida S., Musacchio A., The life and miracles of kinetochores. EMBO J. 28, 2511–2531 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corless S., Höcker S., Erhardt S., Centromeric RNA and its function at and beyond centromeric chromatin. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 4257–4269 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNulty S. M., Sullivan L. L., Sullivan B. A., Human centromeres produce chromosome-specific and array-specific alpha satellite transcripts that are complexed with CENP-A and CENP-C. Dev. Cell 42, 226–240.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ten Hagen K. G., Gilbert D. M., Willard H. F., Cohen S. N., Replication timing of DNA sequences associated with human centromeres and telomeres. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 6348–6355 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massey D. J., Kim D., Brooks K. E., Smolka M. B., Koren A., Next-generation sequencing enables spatiotemporal resolution of human centromere replication timing. Genes 10, 269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aze A., Sannino V., Soffientini P., Bachi A., Costanzo V., Centromeric DNA replication reconstitution reveals DNA loops and ATR checkpoint suppression. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 684–691 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabeche L., Nguyen H. D., Buisson R., Zou L., A mitosis-specific and R loop–driven ATR pathway promotes faithful chromosome segregation. Science 359, 108–114 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasinathan S., Henikoff S., Non-B-form DNA is enriched at centromeres. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 949–962 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Tallec B., et al., Updating the mechanisms of common fragile site instability: How to reconcile the different views? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 4489–4494 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gemble S., et al., Centromere dysfunction compromises mitotic spindle pole integrity. Curr. Biol. 29, 3072–3080.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higa M., Fujita M., Yoshida K., DNA replication origins and fork progression at mammalian telomeres. Genes 8, 112 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindström M. S., et al., Nucleolus as an emerging hub in maintenance of genome stability and cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene 37, 2351–2366 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoffmann S., et al., CENP-A is dispensable for mitotic centromere function after initial centromere/kinetochore assembly. Cell Rep. 17, 2394–2404 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodor D. L., Valente L. P., Mata J. F., Black B. E., Jansen L. E. T., Assembly in G1 phase and long-term stability are unique intrinsic features of CENP-A nucleosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 923–932 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansen L. E. T., Black B. E., Foltz D. R., Cleveland D. W., Propagation of centromeric chromatin requires exit from mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 176, 795–805 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobel R. E., Cook R. G., Perry C. A., Annunziato A. T., Allis C. D., Conservation of deposition-related acetylation sites in newly synthesized histones H3 and H4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1237–1241 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bodor D. L., et al., The quantitative architecture of centromeric chromatin. eLife 3, e02137 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giunta S., Centromere chromosome orientation fluorescent in situ hybridization (Cen-CO-FISH) detects sister chromatid exchange at the centromere in human cells. Bio Protoc. 8, e2792 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norio P., Schildkraut C. L., Visualization of DNA replication on individual Epstein-Barr virus episomes. Science 294, 2361–2364 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchal C., Sima J., Gilbert D. M., Control of DNA replication timing in the 3D genome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 721–737 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Housman D., Huberman J. A., Changes in the rate of DNA replication fork movement during S phase in mammalian cells. J. Mol. Biol. 94, 173–181 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fachinetti D., et al., Replication termination at eukaryotic chromosomes is mediated by Top2 and occurs at genomic loci containing pausing elements. Mol. Cell 39, 595–605 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendez-Bermudez A., et al., Genome-wide control of heterochromatin replication by the telomere capping protein TRF2. Mol. Cell 70, 449–461.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García-Muse T., Aguilera A., R loops: From physiological to pathological roles. Cell 179, 604–618 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boguslawski S. J., et al., Characterization of monoclonal antibody to DNA⋅RNA and its application to immunodetection of hybrids. J. Immunol. Methods 89, 123–130 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chedin F., Benham C. J., Emerging roles for R-loop structures in the management of topological stress. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 4684–4695 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bury L., et al., Alpha-satellite RNA transcripts are repressed by centromere-nucleolus associations. eLife 9, e59770 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan F. L., et al., Active transcription and essential role of RNA polymerase II at the centromere during mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1979–1984 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perea-Resa C., Bury L., Cheeseman I. M., Blower M. D., Cohesin removal reprograms gene expression upon mitotic entry. Mol. Cell 78, 127–140.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamperl S., Bocek M. J., Saldivar J. C., Swigut T., Cimprich K. A., Transcription-replication conflict orientation modulates R-loop levels and activates distinct DNA damage responses. Cell 170, 774–786.e19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quivy J.-P., et al., A CAF-1 dependent pool of HP1 during heterochromatin duplication. EMBO J. 23, 3516–3526 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeman M. K., Cimprich K. A., Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 2–9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burrell R. A., et al., Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature 494, 492–496 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minocherhomji S., et al., Replication stress activates DNA repair synthesis in mitosis. Nature 528, 286–290 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gelot C., Magdalou I., Lopez B. S., Replication stress in mammalian cells and its consequences for mitosis. Genes 6, 267–298 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumann C., Körner R., Hofmann K., Nigg E. A., PICH, a centromere-associated SNF2 family ATPase, is regulated by Plk1 and required for the spindle checkpoint. Cell 128, 101–114 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Germann S. M., et al., TopBP1/Dpb11 binds DNA anaphase bridges to prevent genome instability. J. Cell Biol. 204, 45–59 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaulich M., Cubizolles F., Nigg E. A., On the regulation, function, and localization of the DNA-dependent ATPase PICH. Chromosoma 121, 395–408 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gemble S., et al., Topoisomerase IIα prevents ultrafine anaphase bridges by two mechanisms. Open Biol. 10, 190259 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Umbreit N. T., et al., Mechanisms generating cancer genome complexity from a single cell division error. Science 368, eaba0712 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong Y. L., et al., Cell biology. Reversible centriole depletion with an inhibitor of Polo-like kinase 4. Science 348, 1155–1160 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mejlvang J., et al., New histone supply regulates replication fork speed and PCNA unloading. J. Cell Biol. 204, 29–43 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeitlin S. G., et al., Double-strand DNA breaks recruit the centromeric histone CENP-A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15762–15767 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nechemia-Arbely Y., et al., DNA replication acts as an error correction mechanism to maintain centromere identity by restricting CENP-A to centromeres. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 743–754 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klemm S. L., Shipony Z., Greenleaf W. J., Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 207–220 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sfeir A., et al., Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell 138, 90–103 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Madireddy A., et al., FANCD2 facilitates replication through common fragile sites. Mol. Cell 64, 388–404 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muller H., Gil J. Jr, Drinnenberg I. A., The impact of centromeres on spatial genome architecture. Trends Genet. 35, 565–578 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Potapova T. A., et al., Superresolution microscopy reveals linkages between ribosomal DNA on heterologous chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 218, 2492–2513 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Maehara K., Takahashi K., Saitoh S., CENP-A reduction induces a p53-dependent cellular senescence response to protect cells from executing defective mitoses. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 2090–2104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee S.-H., Itkin-Ansari P., Levine F., CENP-A, a protein required for chromosome segregation in mitosis, declines with age in islet but not exocrine cells. Aging (Albany, NY) 2, 785–790 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Cecco M., et al., Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell 12, 247–256 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Swanson E. C., Manning B., Zhang H., Lawrence J. B., Higher-order unfolding of satellite heterochromatin is a consistent and early event in cell senescence. J. Cell Biol. 203, 929–942 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dillinger S., Straub T., Németh A., Nucleolus association of chromosomal domains is largely maintained in cellular senescence despite massive nuclear reorganisation. PLoS One 12, e0178821 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Amor D. J., et al., Human centromere repositioning “in progress.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6542–6547 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trotter E. W., Hagan I. M., Release from cell cycle arrest with Cdk4/6 inhibitors generates highly synchronized cell cycle progression in human cell culture. Open Biol. 10, 200200 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skene P. J., Henikoff J. G., Henikoff S., Targeted in situ genome-wide profiling with high efficiency for low cell numbers. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1006–1019 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.