Abstract

Background

It is reported that osteoporosis commonly occurs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), whereas the association between osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (OA) remains controversial. Our aim in this study was to investigate the association between BMD, as a marker of osteoporosis, and OA and RA among adults 20−59 years of age, using a population-based sample from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

Our analysis was based on the NHANES data collected between 2011 and 2018. Data regarding arthritis status and the type of arthritis (OA or RA) were obtained from questionnaires. Lumbar BMD was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. The association between OA, RA, and lumbar BMD was evaluated using logistic regression models. Subgroup analyses, stratified by gender and race, were performed. The association between duration of arthritis and lumbar BMD was also investigated.

Results

A total of 11,094 adults were included in our study. Compared to the non-arthritis group, participants with OA had a higher lumbar BMD (β = 0.023, 95% CI 0.011–0.035), with no significant association between lumbar BMD and RA (β = 0.014, 95% CI − 0.003 to 0.031). On subgroup analyses stratified by gender, males with OA had a higher lumbar BMD compared to those without OA (β = 0.047, 95% CI 0.028–0.066). In females, OA was not associated with lumbar BMD (β = 0.007, 95% CI − 0.008 to 0.021). There was no association between lumbar BMD and RA in both males (β = 0.023, 95% CI − 0.003 to 0.048) and females (β = 0.008, 95% CI − 0.015 to 0.031). Duration of arthritis was not associated with lumbar BMD for both OA (β = − 0.0001, 95% CI − 0.0017 to 0.0015) and RA (β = 0.0006, 95% CI − 0.0012 to 0.0025).

Conclusions

Lumbar BMD was associated with OA but not with RA. While a higher lumbar BMD was associated with OA in males, but not in females. Our findings may improve our understanding between OA, RA, and bone health.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Degenerative arthritis, Rheumatoid arthritis, Bone health, NHANES

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP), osteoarthritis (OA), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are pathologies of the musculoskeletal system that cause pain, movement impairments, and possibly permanent disability [1]. With aging of the general population, it is estimated that 1 in 4 adults in developed countries are affected by OP, OA, and/or RA [2, 3]. The pathophysiology of these three conditions is different; however, RA is an autoimmune disease of unknown etiology, associated with a homeostatic imbalance [4]. By contrast, OA is largely considered a biomechanical disorder of articular joints, with its onset and development being closely related to changes in inflammatory and catabolic functions of the body [5]. OP is a systemic disease associated with a marked loss of bone mineral density (BMD). As two notable silent rheumatic diseases, OA and OP have been included on the World Health Organization’s list of disabling disease [1, 6].

However, a clear association between OP and OA has not been clearly defined and remains an issue of controversy, while OP is commonly associated with RA [7–10]. Our aim in this study was to investigate the association between BMD, as a marker of OP, and OA and RA among adults 20–59 years of age, using a population-based sample from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

Study population

The NHANES program is a series of surveys focusing on the health topics of the general population, of all ages, in the United States (US). A multistage, complex clustered, probability design is used for data collection and analysis, rather than being based on a simple random sample of the US population [11].

For our study, we used NHANES data collected between 2011 and 2018. The study population was restricted to adults 20–59 years of age (n = 14,934). From this eligible group, 3840 individuals were excluded for the following reasons: absence of an arthritis diagnosis (n = 23) or lumbar BMD measure (n = 3398), or a cancer diagnosis (n = 419) were excluded. A total of 11,094 individuals were included in our analysis.

Our study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Within the NHANES program, all participants have provided consent for the use of their anonymized information for research purposes [12].

Arthritis

A diagnosis of arthritis was based on the medical conditions questionnaires collected by interview as part of the NHANES program. Participants were asked if they had ever been told by their doctor or other health professional that they had arthritis. If “yes”, they were asked to classify their arthritis diagnosis as OA, RA, psoriatic arthritis, other, or do not know/refuse to answer. The duration of arthritis was determined in years as the “age at screening” minus the “age at the time of diagnosis.”

Lumbar BMD

The lumbar spine is one site that is typically evaluated for the assessment and treatment of OP, with BMD measurement at this site having been used as a marker of OP in clinical trials for over three decades [13]. BMD measures within the NHANES were obtained using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, which is the most widely accepted method. Within the NHANES program, DXA scans were performed using a Hologic Discovery model A densitometers (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts), with data analyzed using Hologic APEX (version 4.0) software. Further details of the DXA examination protocol are available on the NHANES website.

Collected data

The following demographic data were collected by interview questionnaires: age, gender, race, educational level, ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, and smoked history. Race was quantified as follows: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, and other race, including being multi-racial. Vigorous recreational activities was based on an individual’s self-reported answer to the following question: “Do you do any vigorous-intensity sports, fitness, or recreational activities that cause large increases in breathing or heart rate like running or basketball for at least 10 minutes continuously?.” A positive smoking history was defined as ≥ 100 cigarettes smoked in one’s life.

Laboratory data

Biospecimens were collected for laboratory analysis to provide detailed information on each individual’s nutritional status and general health. Biospecimens were collected, processed, and stored in the mobile examination center until shipping to a laboratory for analysis. The following biomarkers were collected: blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum potassium, serum sodium, serum phosphorus, serum uric acid, and serum calcium.

Statistical analysis

To assure national representation, we used weighted analyses as recommended by the analytical guidelines of the NCHS. The P value of the difference between individuals with and without arthritis was calculated using a weighted chi-squared test for categorical variables and a weighted linear regression model for continuous variables.

The association between arthritis (OA and RA) and lumbar BMD was examined using a multivariable logistic regression. Three models were constructed, as follows: model 1, no adjustment for covariates; model 2, adjusted for age, gender, and race; model 3, adjusted for age, gender, race, educational level, body mass index (BMI), ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, smoked history, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum potassium, serum sodium, serum phosphorus, serum uric acid, and serum calcium were adjusted. In addition, in alignment with The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline [14], we performed subgroup analyses, stratified by age and gender, to make better use of the data. We also performed multivariable logistic regression to explore the association between duration of OA and RA and lumbar BMD. All analyses were performed using package R (version 3.4.3, http://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats software (http://www.empowerstats.com). The significance level was set at 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Study sample

The characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1, with relevant features between the non-arthritis and arthritis group summarized, as follows. Compared to the non-arthritis group, the arthritis group was older (mean age 37.59 ± 11.34 years versus 47.99 ± 9.36 years), and had a higher proportion of women than men (46.17% versus 56.08%). Race, educational level, BMI, vigorous recreational activities, smoked history, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum uric acid, serum sodium, and serum calcium were also significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristic of study sample with and without arthritis

| Arthritis (n = 1510) | Non-arthritis (n = 9584) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.99 ± 9.36 | 37.59 ± 11.34 | < 0.001 |

| Age groups | |||

| 20–29 years | 5.97 | 30.31 | < 0.001 |

| 30–39 years | 12.38 | 26.12 | |

| 40–49 years | 27.09 | 24.53 | |

| 50–59 years | 54.56 | 19.04 | |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 43.92 | 53.83 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 56.08 | 46.17 | |

| Race (%) | |||

| Mexican American | 6.07 | 11.06 | < 0.001 |

| Other Hispanic | 5.07 | 7.71 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.41 | 58.80 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.47 | 12.32 | |

| Other race—including multi-racial | 7.97 | 10.11 | |

| Educational level (%) | |||

| Less than 9th grade | 3.94 | 3.96 | < 0.001 |

| 9th–11th grade | 11.83 | 9.02 | |

| High school graduate/GED or equivalent | 22.99 | 21.67 | |

| Some college or AA degree | 35.13 | 32.47 | |

| College graduate or above | 26.11 | 32.87 | |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0.01 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.71 ± 8.00 | 28.56 ± 6.56 | < 0.001 |

| Ratio of family income to poverty | 2.95 ± 1.72 | 2.94 ± 1.66 | 0.821 |

| Vigorous recreational activities (%) | |||

| Yes | 19.99 | 36.63 | < 0.001 |

| No | 80.01 | 63.37 | |

| Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life (%) | |||

| Yes | 51.38 | 38.63 | < 0.001 |

| No | 48.59 | 61.35 | |

| Not recorded | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 4.82 ± 1.71 | 4.54 ± 1.49 | < 0.001 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 70.60 ± 4.45 | 71.58 ± 4.29 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.11 ± 1.04 | 4.91 ± 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 71.50 ± 22.57 | 66.32 ± 22.73 | < 0.001 |

| Serum uric acid(μmol/L) | 323.79 ± 84.78 | 318.53 ± 80.72 | 0.019 |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | 139.12 ± 2.43 | 139.25 ± 2.21 | 0.037 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 3.95 ± 0.33 | 3.97 ± 0.31 | 0.122 |

| Serum phosphorus (mmol/L) | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 1.20 ± 0.18 | 0.397 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 2.34 ± 0.09 | 2.34 ± 0.08 | 0.013 |

| Disease duration of arthritis (years) | 9.20 ± 8.90 | / | |

| Which type of arthritis was it? (%) | |||

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 41.61 | / | / |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 17.45 | / | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2.73 | / | |

| Other | 0.17 | / | |

| Do not know or refused | 24.20 | / | |

| Lumbar bone mineral density (g/cm2) | 1.05 ± 0.16 | 1.04 ± 0.15 | 0.086 |

Mean ± SD for continuous variables: P value was calculated by weighted linear regression model

Percent for categorical variables: P value was calculated by weighted chi-square test

Multiple regression model

As shown in Table 2, the association between arthritis and lumbar BMD was not significant in the unadjusted model (β = 0.007, 95% CI − 0.001 to 0.015). However, a significant association between arthritis and lumbar BMD was identified after adjusting for age, gender, and race (model 2: β = 0.017, 95% CI 0.008–0.025; model 3: β = 0.018, 95% CI 0.010–0.027). Compared to the non-arthritis group, individuals with OA or degenerative arthritis had a higher lumbar BMD (β = 0.023, 95% CI 0.011–0.035), with no significant association between the lumbar BMD and RA (β = 0.014, 95% CI − 0.003 to 0.031).

Table 2.

Associations between arthritis and lumbar bone mineral density

| Model 1, β (95% CI, P) | Model 2, β (95% CI, P) | Model 3, β (95% CI, P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Arthritis | 0.007 (− 0.001, 0.015) 0.0861 | 0.017 (0.008, 0.025) 0.0001 | 0.018 (0.010, 0.027) < 0.0001 |

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 0.013 (0.001, 0.025) 0.0293 | 0.023 (0.012, 0.035) 0.0001 | 0.023 (0.011, 0.035) 0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.000 (− 0.017, 0.018) 0.9733 | 0.010 (− 0.007, 0.027) 0.2599 | 0.014 (− 0.003, 0.031) 0.1074 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0.005 (− 0.039, 0.049) 0.8177 | 0.020 (0.000, 0.039) 0.0445 | 0.024 (0.005, 0.043) 0.0133 |

| Do not know or refused | 0.000 (− 0.015, 0.015) 0.9712 | 0.008 (− 0.006, 0.023) 0.2665 | 0.011 (− 0.004, 0.026) 0.1350 |

Model 1 no covariates were adjusted; Model 2 age, gender, and race were adjusted; Model 3 age, gender, race, educational level, body mass index, ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum uric acid, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium were adjusted

Subgroup analyses

In the subgroup analyses stratified by gender (Table 3), the lumbar BMD was higher among males with OA or degenerative arthritis than those without (β = 0.047, 95% CI 0.028–0.066). However, among females, lumbar BMD was not related to OA or degenerative arthritis (β = 0.007, 95% CI − 0.008 to 0.021). There was no association between lumbar BMD and RA in either males (β = 0.023, 95% CI − 0.003 to 0.048) or females (β = 0.008, 95% CI − 0.015 to 0.031).

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses stratified by gender

| Model 1, β (95% CI, P) | Model 2, β (95% CI, P) | Model 3, β (95% CI, P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 0.045 (0.026, 0.065) < 0.0001 | 0.053 (0.034, 0.072) < 0.0001 | 0.047 (0.028, 0.066) < 0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.010 (− 0.016, 0.036) 0.4569 | 0.021 (− 0.005, 0.046) 0.1139 | 0.023 (− 0.003, 0.048) 0.0776 |

| Female | |||

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | − 0.012 (− 0.026, 0.003) 0.1158 | 0.005 (− 0.010, 0.020) 0.4922 | 0.007 (− 0.008, 0.021) 0.3526 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | − 0.010 (− 0.034, 0.013) 0.3941 | 0.001 (− 0.022, 0.024) 0.9418 | 0.008 (− 0.015, 0.031) 0.5157 |

Adjusted for age, race, educational level, body mass index, ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum uric acid, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium

In the subgroup analyses stratified by race (Table 4), non-Hispanic White adults with OA or degenerative arthritis had a higher lumbar BMD compared to those without (β = 0.014, 95% CI − 0.003 to 0.031).

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses stratified by race

| Model 1, β (95% CI, P) | Model 2, β (95% CI, P) | Model 3, β (95% CI, P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic White | |||

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 0.009 (− 0.009, 0.026) 0.3439 | 0.018 (− 0.000, 0.036) 0.0501 | 0.019 (0.001, 0.037) 0.0382 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | − 0.015 (− 0.045, 0.015) 0.3222 | − 0.007 (− 0.036, 0.023) 0.6699 | 0.001 (− 0.028, 0.031) 0.9232 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | |||

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | − 0.020 (− 0.050, 0.009) 0.1806 | 0.003 (− 0.027, 0.034) 0.8340 | 0.007 (− 0.024, 0.037) 0.6611 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.008 (− 0.031, 0.046) 0.6947 | 0.032 (− 0.007, 0.071) 0.1105 | 0.032 (− 0.007, 0.071) 0.1035 |

| Mexican American | |||

| Non-arthritis | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 0.015 (− 0.025, 0.056) 0.4579 | 0.032 (− 0.008, 0.073) 0.1189 | 0.017 (− 0.023, 0.057) 0.4103 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | − 0.022 (− 0.061, 0.018) 0.2899 | − 0.004 (− 0.044, 0.036) 0.8602 | − 0.006 (− 0.046, 0.033) 0.7621 |

Adjusted for age, gender, educational level, body mass index, ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum uric acid, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium

Associations between disease duration and lumbar BMD

As shown in Table 5, there was no association between the lumbar BMD and either OA or degenerative arthritis (β = − 0.0001, 95% CI − 0.0017 to 0.0015) or RA (β = 0.0006, 95% CI − 0.0012 to 0.0025).

Table 5.

Associations between disease duration of arthritis and lumbar bone mineral density

| Disease duration of arthritis (years) | Model 1, β (95% CI) P value | Model 2, β (95% CI) P value | Model 3, β (95% CI) P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis | 0.0005 (− 0.0021, 0.0011) 0.5312 | − 0.0003 (− 0.0020, 0.0013) 0.6746 | − 0.0001 (− 0.0017, 0.0015) 0.8619 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.0013 (− 0.0005, 0.0032) 0.1596 | 0.0013 (− 0.0005, 0.0032) 0.1649 | 0.0006 (− 0.0012, 0.0025) 0.4979 |

Adjusted for age, race, educational level, body mass index, ratio of family income to poverty, vigorous recreational activities, smoked at least 100 cigarettes in life, blood urea nitrogen, total protein, total cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase, serum uric acid, serum sodium, serum potassium, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium

Discussion

The main findings of our study were as follows: First is the positive association between a higher lumbar BMD and OA among males, but not among females. Second, there was no association between the lumbar BMD and RA, in both females and males.

The association between OP and OA has been an issue of controversy for a number of years. Both diseases depend on bone metabolism and are positively correlated with aging. In a study of 359 postmenopausal women 50–89 years of age, Povoroznyuk et al. [15] identified that women with symptomatic OA had a significantly higher lumbar BMD compared to controls. By contrast, a cross-sectional analysis of a Korean national survey reported a negative association between lumbar BMD and knee OA [16]. A recent prospective study provided strong evidence that high femoral neck BMD is a prognostic risk factor for the development of knee and hip radiographic OA [17]. In addition, higher BMD has been shown to reduce the risk of fractures among both men and women [18, 19]. The concomitant presence of OP and OA in patients with hip or spine OA has also been reported [20, 21]. In a study of 80 post-menopausal women with hand OA, including Heberden’s nodes which is a characteristic feature of primary generalized OA, and 80 age-matched women without OA, the authors found that primary generalized OA is not protective against osteoporosis [22]. The results of a cross-sectional study of 2855 individuals ≥ 40 years of age identified a significant association between elevated phalangeal BMD and radiographic knee OA among women but not men [23].

The biologic mechanism by which BMD influences OA has not been established. Previous statistically significant findings may result from uncontrolled and unmeasured confounding factors, such as skeletal growth factors [24], bone geometry [25, 26], bone morphology [27], and genetics [28]. A previous cohort analysis from the Framingham Study reported that a higher BMD decreased the risk of progression of radiographic knee OA, defined by the presence of osteophytes on radiographs [29]. The authors postulated that a higher BMD reduced the risk of joint space loss; however, once OA developed, a higher BMD might increase the risk of osteophyte formation. Other studies have also reported a positive association between BMD and osteophytes, with a negative association with joint space narrowing [30, 31]. In an animal experiment, knee OA induction by anterior cruciate ligament transection in young growing female rats induced greater bone loss in the weight-bearing bone than in non-weight-bearing bone during OA progression [32]. From a cellular point of view, OP patients exhibit an imbalance between the osteoblast and osteoclast activity [33], and dysregulation of bone remodeling contributes to the development of OA [34]. In our study, we identified a sex-specific difference in the association between lumbar BMD and OA. One possible explanation is that higher BMI and greater weight-bearing activities, which are more likely in men than in women, might both increase the risk of damage to articular cartilage leading to OA and also be beneficial to the preservation of bone mass.

The absence of an association between OP and RA may be a result of multiple factors. Of note, a link between OP and RA has previously been postulated, with this association being mediated via several mechanisms, including pro-inflammatory state, glucocorticoids use, low level of physical activity, and the classic risk factors for OP [35]. However, in a cross-sectional study of 152 Korean adults ≥ 50 years of age, Kweon et al. [36] found no significant difference in lumbar BMD between patients with and without RA. In a study of 138 postmenopausal women with RA, Mori et al. [37] found that disease duration was significantly related to BMD using multivariate linear regression analyses. In contrast, a study of 76 patients with RA identified a lower than expected BMD in patients in the first decade of their RA disease compared to reference population [38]. In a study of 299 Korean female patients with RA, Lee et al. [39] found no significant association between disease duration of RA and BMD. In our own analysis, we did not identify a significant association between BMD and RA, or disease duration of RA, and this both in males and females. Differences across studies are likely attributable to variations among studies, including demographic characteristics, sample size, study design, and confounding variables controlled for.

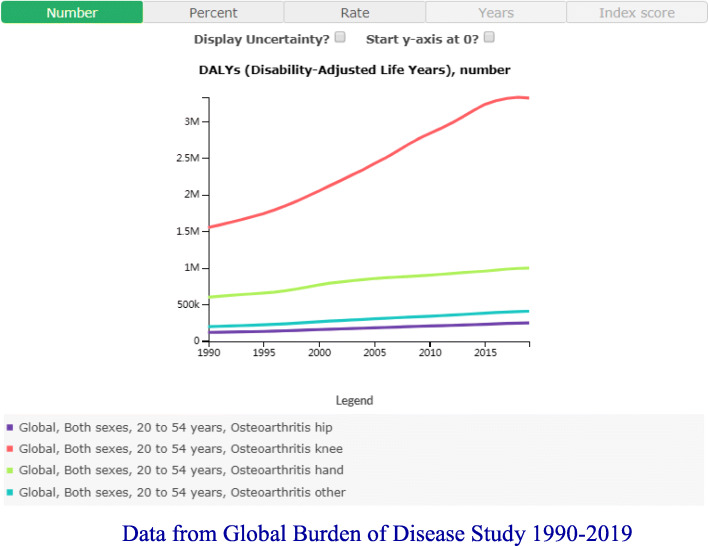

The strengths of our study include a population-based sample with a wide age range that is generalizable to a community population, subgroup analyses for sensitivity test, and adjustment for many potential confounders. However, the limitations of our study also need to be acknowledged. First, due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we were unable to elucidate the causal relationship between arthritis and BMD. Longitudinal studies investigating the causality between them are needed. Second, the diagnosis of arthritis was based on patients’ self-report which may lead to bias. However, the consistency between self-reported arthritis and clinical confirmation has previously been documented [40, 41]. Third, the missing information on different sites of arthritis precludes us to estimate the associations between OA, RA, and BMD at specific sites. For example, primary osteoarthritis includes nonuniform joint space loss, osteophyte formation, cyst formation, and subchondral sclerosis at the lumbar spine which might increase the DXA measures of lumbar BMD, which is a considerable confounding factor in our study. However, the data from the Global Burden of Disease Study indicated that knee OA accounts for the vast majority of young and middle-aged adults [42] (Fig. 1). Fourth, our study results cannot be generalized as we excluded populations with special health concerns, such as individuals with a history of cancer. Finally, there might be other confounding factors we did not control for in our study, such as the use of glucocorticoids used for the treatment of RA. We do note, however, a previous study which did not identify a significant association between the cumulative glucocorticoid dose and BMD after adjustment for confounding variables [39]. The results of a population-based study similarly showed no significant difference in BMD between patients with RA treated with corticosteroids and a non-steroid group, indicative that an independent effect of corticosteroids on BMD is likely negligible [43].

Fig. 1.

Data from Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2019

In summary, lumbar BMD was associated with OA but not RA. Moreover, we identified a sex-specific effect, with a higher lumbar BMD associated with OA in males, but not in females. Our findings may improve our understanding between OA, RA, and bone health. Additional studies examining the association between BMD and OA and RA are warranted to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the time and effort given by participants during the data collection phase of the NHANES project.

Abbreviations

- OP

Osteoporosis

- OA

Osteoarthritis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- NHANES

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- US

The United States

- NCHS

The National Center for Health Statistics

- DXA

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- BMI

Body mass index

- STROBE

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

Authors’ contributions

ZXZ, GFH, and FJ contributed to data collection, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. XCY contributed to study design and editing of the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics review board of the National Center for Health Statistics approved all NHANES protocols and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Franco-Trepat E, Guillan-Fresco M, Alonso-Perez A, Jorge-Mora A, Francisco V, Gualillo O, Gomez R. Visfatin connection: present and future in osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital Signs: Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):246–253. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic C . Rheumatoid arthritis: national clinical guideline for management and treatment in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK) Royal College of Physicians of London.; 2009. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2205–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez R, Villalvilla A, Largo R, Gualillo O, Herrero-Beaumont G. TLR4 signalling in osteoarthritis--finding targets for candidate DMOADs. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(3):159–170. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geusens PP, van den Bergh JP. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis: shared mechanisms and epidemiology. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28(2):97–103. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clayton ES, Hochberg MC. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and spondylarthropathies. Curr Osteoporosis Rep. 2013;11(4):257–262. doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0172-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramonda R, Sartori L, Ortolan A, Frallonardo P, Lorenzin M, Punzi L, Musacchio E. The controversial relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis: an update on hand subtypes. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(10):954–960. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Im GI, Kim MK. The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2014;32(2):101–109. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dequeker J, Aerssens J, Luyten FP. Osteoarthritis and osteoporosis: clinical and research evidence of inverse relationship. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(5):426–439. doi: 10.1007/BF03327364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon CF, Weisman MH. US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Arthritis Initiatives, Methodologies and Data. Rheumatic Dis Clin North Am. 2018;44(2):215–265. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, Ostchega Y, Lewis BG, Dostal J. National health and nutrition examination survey: plan and operations, 1999-2010. Vital Health Stat Ser 1. 2013;(56):1–37. [PubMed]

- 13.Kanis JA, Johnell O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(3):229–238. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Povoroznyuk VV, Zaverukha NV, Musiienko AS. Bone mineral density and trabecular bone score in postmenopausal women with knee osteoarthritis and obesity. Wiad Lek. 2020;73(3):529–533. doi: 10.36740/WLek202003124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YH, Lee JS, Park JH. Association between bone mineral density and knee osteoarthritis in Koreans: the Fourth and Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(11):1511–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergink AP, Rivadeneira F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Zillikens MC, Ikram MA, Uitterlinden AG, van Meurs JBJ. Are bone mineral density and fractures related to the incidence and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, and hand in elderly men and women? The Rotterdam Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2019;71(3):361–369. doi: 10.1002/art.40735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(11):1947–1954. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.11.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings SR, Cawthon PM, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Fink HA, Orwoll ES. BMD and risk of hip and nonvertebral fractures in older men: a prospective study and comparison with older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(10):1550–1556. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan MY, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Bone mineral density and association of osteoarthritis with fracture risk. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2014;22(9):1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lingard EA, Mitchell SY, Francis RM, Rawlings D, Peaston R, Birrell FN, McCaskie AW. The prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with severe hip and knee osteoarthritis awaiting joint arthroplasty. Age Ageing. 2010;39(2):234–239. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aigul Z, Peyman Y. The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis in patients with primary generalized osteoarthritis. Turkish J Rheumat. 2013;28(3):163–172. doi: 10.5606/tjr.2013.2984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng ZH, Zeng C, Li YS, Yang T, Li H, Wei J, Lei GH. Relation between phalangeal bone mineral density and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:71. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0918-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter DJ, Spector TD. The role of bone metabolism in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2003;5(1):15–19. doi: 10.1007/s11926-003-0078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding C, Cicuttini F, Jones G. Tibial subchondral bone size and knee cartilage defects: relevance to knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(5):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javaid MK, Lane NE, Mackey DC, Lui LY, Arden NK, Beck TJ, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC. Changes in proximal femoral mineral geometry precede the onset of radiographic hip osteoarthritis: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):2028–2036. doi: 10.1002/art.24639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson AE, Golightly YM, Renner JB, Schwartz TA, Liu F, Lynch JA, Gregory JS, Aspden RM, Lane NE, Jordan JM. Variations in hip shape are associated with radiographic knee osteoarthritis: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(2):405–410. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yau MS, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Liu Y, Lewis CE, Duggan DJ, Renner JB, Torner J, Felson DT, McCulloch CE, Kwoh CK, et al. Genome-wide association study of radiographic knee osteoarthritis in North American Caucasians. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(2):343–351. doi: 10.1002/art.39932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Chaisson CE, McAlindon TE, Evans SR, Aliabadi P, Levy D, Felson DT. Bone mineral density and risk of incident and progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis in women: the Framingham Study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(4):1032–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hart DJ, Cronin C, Daniels M, Worthy T, Doyle DV, Spector TD. The relationship of bone density and fracture to incident and progressive radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee: the Chingford Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(1):92–99. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<92::AID-ART10057>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wen L, Shin MH, Kang JH, Yim YR, Kim JE, Lee JW, Lee KE, Park DJ, Kim TJ, Park YW, et al. The relationships between bone mineral density and radiographic features of hand or knee osteoarthritis in older adults: data from the Dong-gu Study. Rheumatology. 2016;55(3):495–503. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namhong S, Wongdee K, Suntornsaratoon P, Teerapornpuntakit J, Hemstapat R, Charoenphandhu N. Knee osteoarthritis in young growing rats is associated with widespread osteopenia and impaired bone mineralization. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15079. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scimeca M, Salustri A, Bonanno E, Nardozi D, Rao C, Piccirilli E, Feola M, Tancredi V, Rinaldi A, Iolascon G, et al. Impairment of PTX3 expression in osteoblasts: a key element for osteoporosis. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(10):e3125. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruotti N, Corrado A, Cantatore FP. Osteoblast role in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(11):2957–2963. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibanez M, Ortiz AM, Castrejon I, Garcia-Vadillo JA, Carvajal I, Castaneda S, Gonzalez-Alvaro I. A rational use of glucocorticoids in patients with early arthritis has a minimal impact on bone mass. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(2):R50. doi: 10.1186/ar2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kweon SM, Sohn DH, Park JH, Koh JH, Park EK, Lee HN, Kim K, Kim Y, Kim GT, Lee SG. Male patients with rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk of osteoporosis: frequency and risk factors. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(24):e11122. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori Y, Kuwahara Y, Chiba S, Kogre A, Baba K, Kamimura M, Itoi E. Bone mineral density of postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis depends on disease duration regardless of treatment. J Bone Miner Metab. 2017;35(1):52–57. doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0716-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroot EJ, Nieuwenhuizen MG, de Waal Malefijt MC, van Riel PL, Pasker-de Jong PC, Laan RF. Change in bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during the first decade of the disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1254–1260. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1254::AID-ART216>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SG, Park YE, Park SH, Kim TK, Choi HJ, Lee SJ, Kim SI, Lee SH, Kim GT, Lee JW, et al. Increased frequency of osteoporosis and BMD below the expected range for age among South Korean women with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(3):289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Youssef SS, Palmer D. Incorporating patient reported outcome measures in clinical practice: development and validation of a questionnaire for inflammatory arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5):734–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.March LM, Schwarz JM, Carfrae BH, Bagge E. Clinical validation of self-reported osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1998;6(2):87–93. doi: 10.1053/joca.1997.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Global Burden of Disease Study tool. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- 43.Kroger H, Honkanen R, Saarikoski S, Alhava E. Decreased axial bone mineral density in perimenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis--a population based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53(1):18–23. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]