Abstract

Background:

Angiogenesis is critical for tumor growth and metastasis. Dual inhibition of VEGF and PDGFR suppresses angiogenesis. This expansion cohort of a phase I study targeted angiogenesis with sorafenib, bevacizumab and low-dose cyclophosphamide in children and young adults with recurrent solid tumors.

Methods:

An expansion cohort with refractory or recurrent solid tumors were enrolled and received bevacizumab (15mg/kg IV, day 1), sorafenib (90mg/m2 po twice daily, days 1–21) and low-dose cyclophosphamide (50mg/m2 po daily, days 1–21). Each course was 21 days. Toxicities were assessed using CTCAE v3.0 and responses were evaluated by RECIST criteria. Serial bevacizumab pharmacokinetic (PK) studies were performed during course 1.

Results:

Twenty-four patients (15 males; median age 14.5 yrs.; range 1–22 yr) received a median of 6 courses (range 1–18). Twelve patients had a bone or soft tissue sarcoma. The most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic toxicities were hypertension (N=4), hand/foot rash (N=3) and elevated lipase (N=3). The most common grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia (N=7) and lymphopenia (N=17). Three patients (2 synovial sarcoma, 1 rhabdoid tumor) achieved a partial response and 18 had stable disease. The progression-free survival at 3 and 6 months were 78.1% (95% CI 60.6–95.6%) and 54% (95% CI 30.2–78.2%) respectively. Bevacizumab pharmacokinetics in 15 patients was similar to published adult pharmacokinetic results.

Conclusions:

Intravenous bevacizumab combined with oral sorafenib and low-dose cyclophosphamide was tolerated and demonstrated promising activity in a subset of childhood solid tumors.

Keywords: sorafenib, cyclophosphamide, bevacizumab, pediatric, phase I, solid tumors

INTRODUCTION

Despite therapeutic advances and improved survival rates in children with cancer,1 the majority of children and adolescents with metastatic or recurrent solid tumors fare poorly.2 Efforts to intensify therapy have largely failed to improve outcome for patients with high-risk disease.2 Thus new therapies, targeting alternative mechanisms of action, are needed.

Angiogenesis is critical for the growth and dissemination of tumors. The use of antiangiogenic drugs has become the standard of care for various adult cancers including sarcomas.3–7 Significant preclinical work has demonstrated that targeting angiogenesis with dual inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) signaling results in tumor suppression and improved survival.3,8

We previously conducted a phase I dose escalation study of a regimen that included bevacizumab, sorafenib and low-dose cyclophosphamide for the treatment of pediatric and young adult patients with refractory or recurrent solid malignancies. In this trial, the recommended phase II doses (RP2D) were bevacizumab (15mg/kg/dose IV every 21 days), sorafenib (90 mg/m2/dose orally twice daily) and cyclophosphamide (50 mg/m2 orally once daily). Among the 19 patients, the therapy was well-tolerated, and a signal of activity was seen in 5 of 17 evaluable patients with an additional 5 patients demonstrating disease stabilization.9

Given the promising responses and the potential for incorporation of this regimen as a maintenance therapy, we studied an expansion cohort. All patients enrolled in the expansion cohort received the recommended phase II doses identified in the phase I trial. The patients also completed pharmacokinetic and biomarker studies.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

This study (ANGIO1, NCT00665990) was approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from patients and/or parents/legal guardians. Patients with refractory/recurrent solid tumors were eligible for treatment. Details of the patient eligibility is outlined in the Data Supplement.

Protocol Therapy

The treatment doses and schedule for the expansion study were identical to the recommended phase II doses identified in the dose-escalation phase I study.9 Twenty-four patients, representing diverse solid tumor diagnoses, received chemotherapy including: bevacizumab (15mg/kg/dose IV every 21 days), sorafenib (90 mg/m2/dose orally twice daily) and cyclophosphamide (50 mg/m2 orally once daily). Bevacizumab was initially administered over 90 minutes with subsequent doses over 60 minutes and 30 minutes if tolerated. Cyclophosphamide was administered as liquid or tablet.10 Sorafenib was administered as a combination of capsules.11 Capsules were opened and sprinkled on low to moderate fat-containing foods for administration to children who could not swallow capsules. Each course lasted 21 days. Patients could remain on study for a maximum of 24 courses. Dose modifications for treatment-related toxicities are included in the Data Supplement.

Toxicity Assessment

Toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. Patients who received ≥ a single dose of therapy were evaluable for toxicity assessment. Toxicities that were ≥ possibly related to protocol therapy were reported. A dose limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined as any left ventricular systolic dysfunction ≥ grade 2 or any nonhematologic toxicity ≥ grade 3 during the first course of therapy except for, grade 3 nausea and vomiting, grade 3 hypertension well controlled with oral medication, grade 3 infection or fever, grade 3 hypophosphatemia or hypokalemia responsive to oral supplementation, grade 3 elevations in ALT or bilirubin that returned to ≤ 2.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN) for age and ≤ 1.5 × ULN for age, respectively, within 7 days of stopping the drug, and asymptomatic grade 3 elevations in amylase and lipase that resolved to grade 1 within 7 days of drug interruption. Hematologic DLT was defined as an ANC less than 500/mm3 lasting longer than 7 days or platelet count less than 50,000/m3 requiring transfusion on more than 2 occasions in 7 days or grade 3 hemorrhage.

Response Evaluation

Patients had disease evaluations performed at baseline, following courses 1, 2 and subsequently after every other course. Tumor response was assessed using the RECIST criteria.12 Patients with iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (mIBG) positive lesions were evaluable for mIBG response. The response of mIBG-avid lesions was reported using the Curie scale.13,14

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Studies

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies were performed in consenting patients during the first course. Serial serum samples were collected prior to bevacizumab administration, at the end of infusion, and 2, 4.5, 7.5, 24 (± 4 hr.), 48 (± 8), 144 (± 24), 288 (± 24) and 480 (± 24) hours. Additional details are included in the Data Supplement.

Statistical Methods

The exact Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to examine for a difference in distribution of plasma protein levels and CECs and CEPs from baseline to the end of course 1. The tumor response rate was estimated and reported with a 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence interval. Duration of response was defined as the time the RECIST criteria were met for objective response to the date of disease progression. Disease control rate includes all evaluable patients with a response of stable disease or better. Progression free survival was estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier and is reported with ± 1 standard error. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software package (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The characteristics of the 25 eligible patients are listed in Table 1. One patient was removed from study on course 1, day 3 due to rapid progression with spinal cord compression requiring radiation therapy. Twenty-four patients completed 153 courses and received a median of 6 courses (range, 1–18). Twelve patients had a bone or soft tissue sarcoma. One patient who achieved stable disease was censored after four courses of therapy due to the initiation of radiation therapy.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| No. patients | 25 | |

| Age on study (years) | ||

| Median (Range) | 14.5 (1.1–22.4) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male: Female | 15:9 | |

| Histologic diagnosis | ||

| Rhabdoid tumor | 3 | |

| Ewing sarcoma | 3 | |

| Osteosarcoma | 3 | |

| Synovial sarcoma | 3 | |

| Wilms tumor | 3 | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 3 | |

| Other* | 7 | |

| Prior Therapy | ||

| No. of prior systemic regimens [median (range)] | 3 (1–10) | |

| Prior radiotherapy | 19 | |

| Prior doxorubicin | 21 | |

sarcoma NOS (1), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (1), neuroblastoma (2), clear cell sarcoma (1) hepatocellular carcinoma(1), metastatic meningioma (1)

Toxicity

The most common non-hematologic toxicities included grade 1/2 anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, proteinuria and pain. The most common grade 2 (>10% of patients) and all grade 3 and 4 toxicities for all courses (N=153) are listed in Table 2. Two patients experienced a dose limiting toxicity (1 each grade 3 prolonged QTc interval and grade 3 hand/foot syndrome) during course 1. The most common grade 3/4 non-hematologic toxicities were hypertension (N=4), hand/foot syndrome (N=3) and elevated lipase (N=3). The most common grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were neutropenia (N=7) and lymphopenia (N=17).

Table 2.

Adverse events grade ≥2 occurring in greater than 10% of patients and all adverse events ≥ grade 3.

| Adverse Events | n=24, no. (%) ≥ 10% of patients with ≥ grade 2 | n=24, no. (%) All grade ≥3 |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | ||

| Anemia | 6 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Leukopenia | 16 (68) | 11 (46) |

| Lymphopenia | 20 (83) | 17 (71) |

| Neutropenia | 13 (54) | 7 (29) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7 (29) | 3 (13) |

| Nonhematologic | ||

| Anorexia | 3 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Cystitis | 5 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Elevated amylase | 5 (21) | 2 (8) |

| Elevated lipase | 4 (17) | 3 (13) |

| Fatigue | 6 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Hand/Foot Exanthem | 8 (33) | 3 (13) |

| Hematuria | 5 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension | 4 (17) | 4 (17) |

| Hypocalcemia | 3 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Hyponatremia | 2 (8) | 2 (8) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 3 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | 3 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Pneumothorax | 5 (21) | 1 (4) |

| Proteinuria | 9 (38) | 2 (8) |

| Vomiting | 8 (33) | 1 (4) |

| Weight loss | 9 (38) | 2 (8) |

Six patients were taken off study due to a treatment toxicity including 3 for hemorrhagic cystitis (courses 5, 8 and 12) and 1 each for: weight loss (course 8), elevated lipase (course 4) and pneumothorax (course 2). All patients with hemorrhagic cystitis had previously received radiation therapy to the pelvis and the patient with weight loss had a concurrent documented psychological disorder that contributed to her weight loss. Seven patients required a 50% dose reduction of sorafenib due to hand-foot syndrome (HFS). Five patients required a 50% dose reduction of cyclophosphamide (3 for cystitis, 1 neutropenia and 1 thrombocytopenia.) Other significant toxicities included pneumothorax and hypertension. For the 3 patients who developed hypertension, all were well-controlled with oral antihypertensive medications

Eight patients developed a pneumothorax: 3 with grade 1, 4 with grade 2 and 1 with grade 3. Four patients required a temporary placement of a chest tube for management. All patients who developed a pneumothorax had bulky pulmonary disease at study entry. Five of the 8 patients with a pneumothorax had a dramatic improvement in the pulmonary lesions at the time they developed the pneumothorax. The other three patients developed a pneumothorax at the time of progressive pulmonary disease.

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Studies

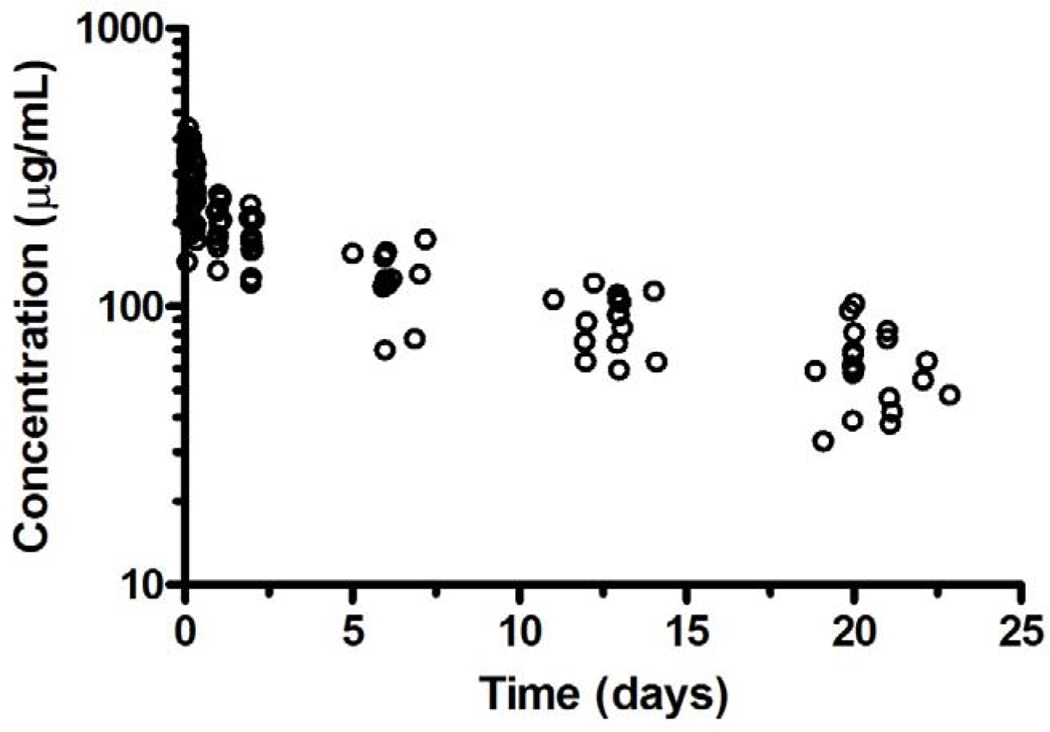

Serial bevacizumab pharmacokinetic studies were performed in 15 patients with a median age of 14.7 years (range, 10.7 – 22.4 years) and weight of 61.1kg (range, 25.6 – 149 kg) (Table 3). Bevacizumab concentration-time data from all 15 patients are presented in Figure 1. A summary of bevacizumab pharmacokinetic parameters is provided in Table 3 and demonstrates that bevacizumab exhibited a modest amount of interpatient variability with a two-fold difference in exposure (AUC0−∞), clearance, and t1/2.

Table 3.

Bevacizumab first dose pharmacokinetic parameters.

| Bevacizumab (15mg/kg) | |

| Number of patients | 15 |

| Cmax (μg/mL) | 331 (206 – 441) |

| tmax (hrs) | 1.9 (1.6 – 4.6) |

| tmax (days) | 0.079 (0.066 – 0.19) |

| t1/2 (days) | 21 (19.1 – 35) |

| AUC0−∞ (μg/mL*day) | 3345 (2566 – 5297) |

| CL (mL/day/kg) | 4.4 (2.8 – 6) |

Values: median (range); Cmax: observed maximum plasma concentration; tmax: time to maximum concentration; t1/2: terminal half-life; AUC0−∞: area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to infinity; CL: clearance

Figure 1.

Representative concentration-time profile for bevacizumab.

Twenty-one patients had plasma samples collected for analysis of plasma proteins (VEGF, soluble VEGFR2, soluble VEGFR3), CECs and CEPs at baseline and during course 1. None of the measured plasma protein levels, CECs (p= 0.67) or CEPs (p=0.47) showed a statistically significant change from baseline to the end of course 1. Further, there was no correlation between overall response and a change in protein levels, CECs or CEPs.

Tumor Response

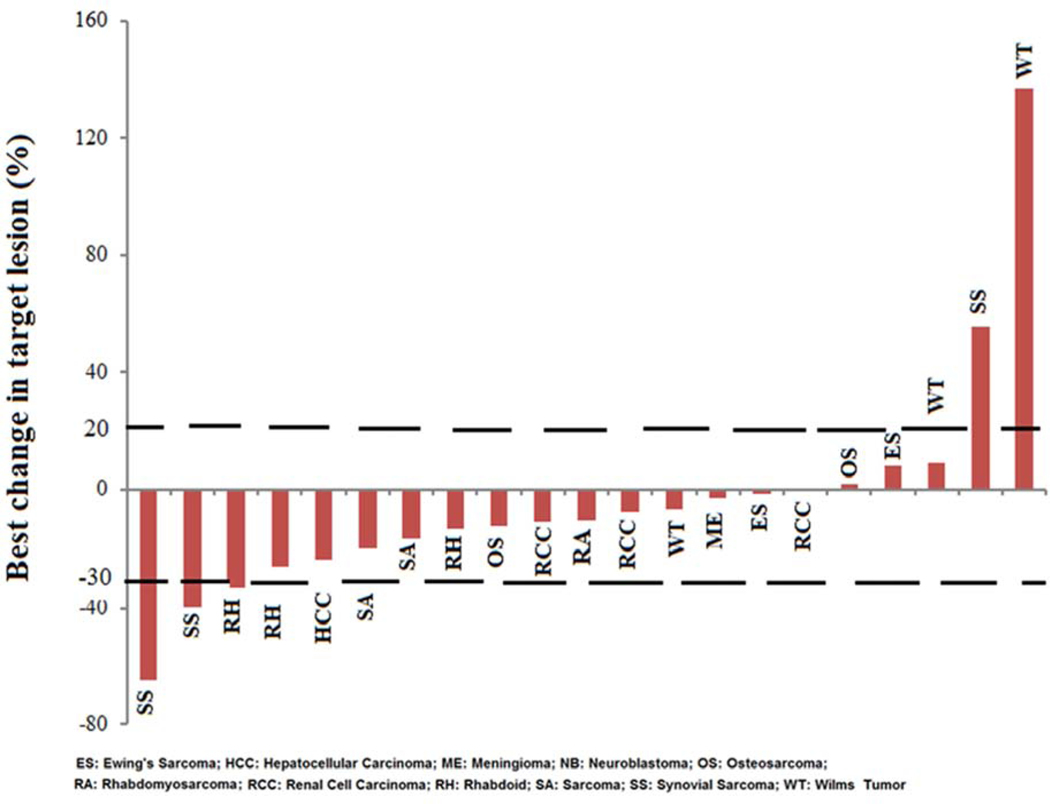

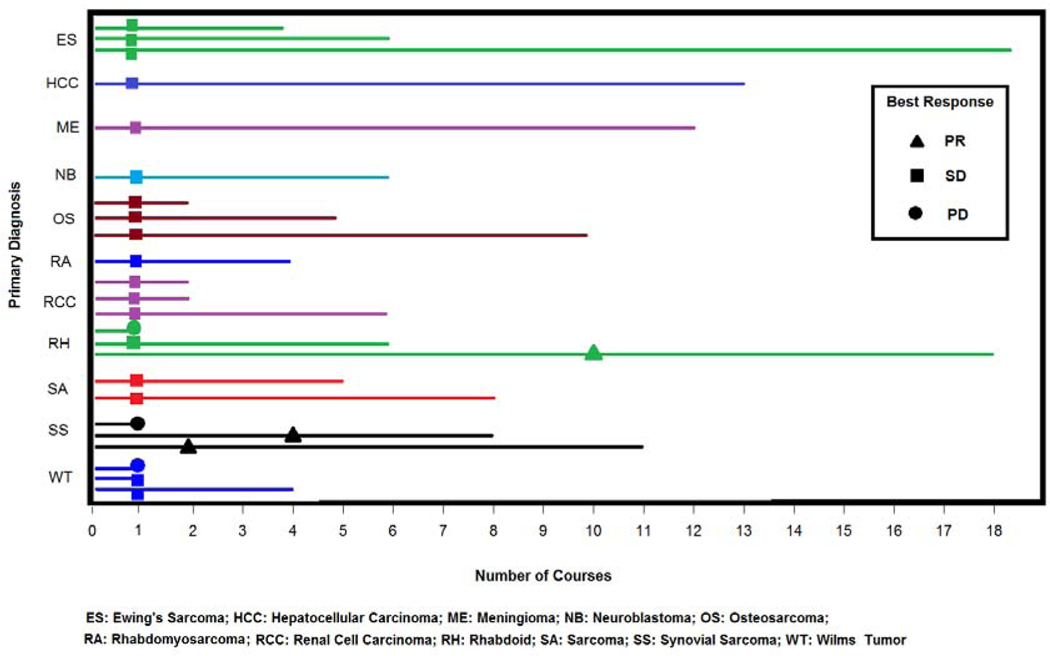

Twenty-one of 24 patients were evaluable for tumor response after course 1 by RECIST. Three patients did not have measurable disease by RECIST criteria and were not evaluable for response. Figure 2 shows a waterfall plot of the maximum percentage of change in the sum of the measured longest diameters of the target lesions for each evaluable patient. Tumor response rates are listed in Table 4. Three patients (2 synovial sarcoma and 1 rhabdoid tumor) had a confirmed partial response (PR, defined as ≥ 30% decrease in the disease measurement) with a median duration of response of 24 weeks (range: 13 – 29 weeks). Fifteen patients had stable disease (SD) and received a median of 7 courses (range, 1–18 courses). Three patients had progressive disease (PD, defined as at least a 20% increase in disease measurement or the development of new lesions) after 1 course. Figure 3 displays the response rate, time to best response and treatment duration (by course number) for each patient per disease diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Waterfall plot of percentage change in the sum of the longest diameter of all target lesions from baseline in 21 patients evaluable for tumor response by RECIST.

Table 4.

Tumor response according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)

| Response/Control rate | |

|---|---|

| Complete response, No. (%) | 0, (0) |

| Partial response, No. (%) | 3, (12.5) |

| Stable disease, No. (%) | 15, (62.5) |

| Progressive disease, No. (%) | 3, (12.5) |

| Not evaluable*, No. (%) | 3, (12.5) |

| Disease control rate, % (95% CI) | 85.7% (65.4 – 97) |

Patients not evaluable by RECIST (included 1 patient each with neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma) did not have target lesions. However, all had stable disease (6 courses, 10 courses, 18 courses respectively) in non-target lesions.

Figure 3.

Number of courses received with time to best response documented at the earliest time of response.

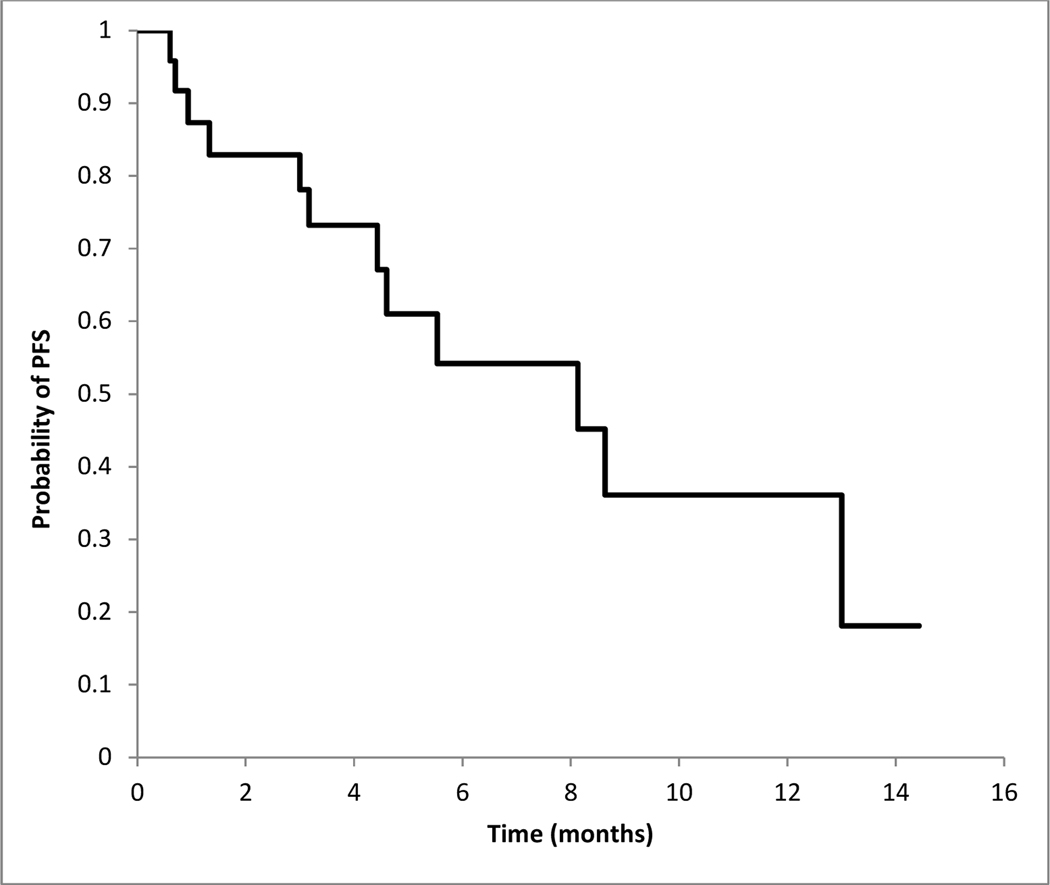

The disease control rate (≥SD) for all evaluable patients was 85.7% (18/21; 95% CI, 65.4% - 97%). The progression-free survival for patients at 3 and 6 months were 78.1% (95% CI 60.6–95.6%) and 54% (95% CI 30.2–78.2%) respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curve for progression-free survival (n=24)

DISCUSSION

This phase I expansion study was performed to further define the feasibility and tolerability of administering the recommended phase II doses of a novel combination of bevacizumab, sorafenib and metronomic cyclophosphamide for the treatment of recurrent childhood solid malignancies. Objective responses were seen in 3 patients and 18 had stable disease. Although 50% (N=12) of the patients required a dose reduction of either sorafenib (N=7) or cyclophosphamide (N=5), the toxicities were clinically manageable. All patients who required a dose reduction had clinical benefit with at least SD and received the treatment regimen with reduced doses for a median of 9 courses (range, 2–18).

The most significant ≥ grade 2 non-hematologic toxicities included a pneumothorax (N=8) and hand foot syndrome (N=8). These toxicities have been described in trials evaluating antiangiogenic agents.15–17 Pneumothorax associated with response to this therapy was previously described in the phase I portion of the study. 9,18 Similar to the phase I, five patients who developed a pneumothorax experienced a rapid decrease in the size of their pulmonary disease, developed a cavitary pulmonary lesion(s) and a small pneumothorax. However, in contrast to the previous trial, three patients developed a pneumothorax with progressive pulmonary disease. Four of the 8 patients required chest tube placement while the other four were managed with observation. For future patients receiving this therapy, those with lung lesions should be monitored for signs and symptoms of pneumothorax including chest pain, tachypnea, or shortness of breath. If these signs or symptoms are present, a chest radiograph should be obtained. For patients with HFS, all who received a 50% dose reduction had resolution of their dermatologic symptoms and continued therapy. Early initiation of pyridoxine therapy and emollients was beneficial and a dose reduction in sorafenib prevented HFS progression or recurrence. Going forward, patients with a history of pelvic irradiation or cystitis, should consider oral mesna in conjunction with cyclophosphamide.

The pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and sorafenib were previously reported.9,17 The pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab are comparable to those previously observed in adults and pediatrics. The median bevacizumab clearance (4.4 mL/day/kg) from this study is similar to that reported from a phase I study in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors (4.1 mL/day/kg) and a population pharmacokinetic study of bevacizumab in osteosarcoma patients (4.8 mL/day/kg). 19,20 The median t1/2 (21 days) from this study is longer than the phase I study (11.7 days) and population pharmacokinetic study (12.2 days) reported previously in pediatrics, but similar to a phase I study (21 days) and population pharmacokinetic study (20 days) in adult patients with a variety of malignancies.21,22 Despite the longer terminal half-life observed in this study, the median AUC0−∞ values are similar to previous pediatric and adult studies.

Agents targeting the VEGF pathway for the treatment of sarcomas have been evaluated over the past decade. Recent studies using PDGFR and VEGFR targeted therapies, such as olaratumab, regorafenib and pazopanib, have suggested activity in the treatment of sarcomas.5,6,23 In this expansion cohort, patients with sarcomas experienced clinical responses and disease stabilization for prolonged periods of time. Although none of the patients experienced a complete response, many patients had delayed time to progression with manageable side effects.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria for PFR (progression-free rate) suggests an active second-line treatment has a 3 month PFR ≥40% and 6 month PFR ≥14%. 24 Using this criteria, our regimen would be considered active. The small sample size of the expansion cohort limits the ability to determine a PFS for a given tumor type; however, when combining sarcoma patients (N=12) treated in the expansion cohort, the 3 and 6 month PFR was 83.3% and 50% respectively. Of note, the progression free survival may have been underestimated due to the large number (N=8) of patients removed from the study due to personal choice (N=2) or physician discretion (N=6). Further details about the reason for removal are unknown.

An intriguing finding in the study were the responses observed in patients with rhabdoid tumors. Pediatric rhabdoid tumors are rare, aggressive malignancies, primarily driven by deletion or loss of function mutations in the SMARCB1 tumor suppressor gene.25 The prognosis at diagnosis is dismal and patients with refractory/recurrent disease rarely respond to therapy.25 Over the last decade, investigators have reported preclinical work that supports VEGF inhibition for the treatment of rhabdoid tumors.26,27 Recently, high-throughput small molecule and CRISPR screening conducted in 16 rhabdoid tumor cell lines revealed receptor tyrosine kinase dependencies underscoring the potential therapeutic benefit of receptor tyrosine kinases for the treatment of this disease.28 In the phase I and expansion portion of this trial, 5 of the 8 patients with rhabdoid tumor experienced SD or better with a median 6 courses of therapy received (range, 1–18); thus, future studies evaluating these agents may be warranted.

In conclusion, the regimen including bevacizumab, sorafenib and cyclophosphamide was feasible to deliver, demonstrated clinical benefit in pediatric and adolescent patients with sarcomas and rhabdoid tumors and warrants further investigation. Although some patients required a dose reduction due to toxicity, all patients continued to demonstrate clinical benefit to therapy at the reduced chemotherapy doses. Although a potential signal change with sVEGFR3 and CEPs was seen in the original phase I cohort, unfortunately no predictive biomarkers of response were identified in the expansion phase. In future trials, this regimen may be considered as maintenance therapy for newly-diagnosed high-risk sarcoma patients or as a palliative measure in patients who desire an outpatient regimen as it provides clinical benefit in select patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Bevacizumab, sorafenib and low-dose cyclophosphamide is tolerated in pediatrics.

This regimen had clinical benefit in patients with sarcomas and rhabdoid tumors.

This regimen may be a maintenance therapy for newly-diagnosed sarcoma patients.

Acknowledgement:

Supported in part by Cancer Center Grant CA23099 and Cancer Center Support CORE Grant P30 CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, Reaman GH, Seibel NL. Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer. 2014;120(16):2497–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perkins SM, Shinohara ET, DeWees T, Frangoul H. Outcome for children with metastatic solid tumors over the last four decades. PloS one. 2014;9(7):e100396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(5):427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1302–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mir O, Brodowicz T, Italiano A, et al. Safety and efficacy of regorafenib in patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma (REGOSARC): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The lancet oncology. 2016;17(12):1732–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tap WD, Jones RL, Van Tine BA, et al. Olaratumab and doxorubicin versus doxorubicin alone for treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: an open-label phase 1b and randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):488–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Muller SP, et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3639–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(23):2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navid F, Baker SD, McCarville MB, et al. Phase I and clinical pharmacology study of bevacizumab, sorafenib, and low-dose cyclophosphamide in children and young adults with refractory/recurrent solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(1):236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy R, Groepper D, Tagen M, et al. Stability of cyclophosphamide in extemporaneous oral suspensions. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(2):295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navid F, Christensen R, Inaba H, et al. Alternative formulations of sorafenib for use in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1642–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(3):205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ady N, Zucker JM, Asselain B, et al. A new 123I-MIBG whole body scan scoring method--application to the prediction of the response of metastases to induction chemotherapy in stage IV neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A(2):256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messina JA, Cheng SC, Franc BL, et al. Evaluation of semi-quantitative scoring system for metaiodobenzylguanidine (mIBG) scans in patients with relapsed neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(7):865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meadows KL, Hurwitz HI. Anti-VEGF therapies in the clinic. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morabito A, De Maio E, Di Maio M, Normanno N, Perrone F. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in clinical trials: current status and future directions. The oncologist. 2006;11(7):753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba H, Panetta JC, Pounds SB, et al. Sorafenib Population Pharmacokinetics and Skin Toxicities in Children and Adolescents with Refractory/Relapsed Leukemia or Solid Tumor Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(24):7320–7330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Interiano RB, McCarville MB, Wu J, Davidoff AM, Sandoval J, Navid F. Pneumothorax as a complication of combination antiangiogenic therapy in children and young adults with refractory/recurrent solid tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(9):1484–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glade Bender JL, Adamson PC, Reid JM, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of bevacizumab in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors: a Children’s Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(3):399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner DC, Navid F, Daw NC, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab in children with osteosarcoma: implications for dosing. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(10):2783–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon MS, Margolin K, Talpaz M, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu JF, Bruno R, Eppler S, Novotny W, Lum B, Gaudreault J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of bevacizumab in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62(5):779–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1879–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Glabbeke M, Verweij J, Judson I, Nielsen OS, Tissue ES, Bone Sarcoma G. Progression-free rate as the principal end-point for phase II trials in soft-tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(4):543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts CW, Biegel JA. The role of SMARCB1/INI1 in development of rhabdoid tumor. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8(5):412–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chauvin C, Leruste A, Tauziede-Espariat A, et al. High-Throughput Drug Screening Identifies Pazopanib and Clofilium Tosylate as Promising Treatments for Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cell reports. 2017;21(7):1737–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maris JM, Courtright J, Houghton PJ, et al. Initial testing of the VEGFR inhibitor AZD2171 by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(3):581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberlick EM, Rees MG, Seashore-Ludlow B, et al. Small-Molecule and CRISPR Screening Converge to Reveal Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Dependencies in Pediatric Rhabdoid Tumors. Cell reports. 2019;28(9):2331–2344.e2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.