Abstract

Background: Best practice guidelines for smoking cessation treatment through primary care advise the 5As model. However, compliance with these guidelines is poor, leaving many smokers untreated. The purpose of this study was to develop and preliminarily evaluate an asynchronous smoking cessation electronic visit (e-visit) that could be delivered proactively through the electronic health record (EHR) to adult smokers treated within primary care. The goal of the e-visit is to automate 5As delivery to ensure that all smokers receive evidence-based cessation treatment. As such, the aims of this study were twofold: (1) to examine acceptability, feasibility, and treatment metrics associated with e-visit utilization and (2) to preliminarily examine efficacy relative to treatment as usual (TAU) within primary care.

Methods: Participants (n = 51) were recruited from primary care practices between November 2018 and October 2019 and randomized 2:1 to receive either the smoking cessation e-visit or TAU. Participants completed assessments of cessation outcomes 1-month and 3-months postenrollment and e-visit analytics data were gathered from the EHR.

Results: Self-report feedback from e-visit participants indicated satisfaction with the intervention and interest in using e-visits again in the future. Nearly all e-visits resulted in prescription of a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved smoking cessation medication. In general, smoking cessation outcomes favored the e-visit condition at both 1 (odds ratios [ORs]: 2.10–5.39) and 3 months (ORs: 1.31–4.67).

Conclusions: These results preliminarily indicate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of this smoking cessation e-visit within primary care. Future studies should focus on larger scale examination of effectiveness and implementation across settings. The clinicaltrials.gov registration number for this trial is NCT04316260.

Keywords: behavioral health, telemedicine, telehealth, m-Health, electronic health records

Introduction

Cigarette smoking causes 480,000 premature deaths each year in the United States.1 At least 70% of adults who smoke cigarettes visit a primary care physician (PCP) annually,2–4 making primary care an ideal venue through which to disseminate evidence-based cessation treatments. United States Public Health Services (USPHS) best practice guidelines advise the 5As model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange) for cessation treatment through primary care.2 However, compliance with these guidelines is poor,5–7 leaving many smokers untreated. Data from the National Lung Screening Trial demonstrated a precipitous drop in 5As compliance across steps: Ask smoking status (77.2%), Advise quitting (75.6%), Assess motivation (63.4%), Assist with referrals (56.4%), and Arrange follow-up (10.4%).6 Obstacles to 5As implementation at the provider level include lack of time, confidence, and familiarity with guidelines.5,7–9 Structured and practical tools that can address these obstacles and extend the reach of evidence-based cessation treatment through primary care are clearly needed.

Consistent with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Meaningful Use guidelines, primary care practices are required to maintain electronic health records (EHRs) with coded smoking status data for adult patients.10,11 These data can be utilized to proactively identify adult smokers and deliver treatment. Several prior trials have leveraged primary care and EHR data within primary care practices to identify smokers and offer telehealth treatment.12–15 Together, existing proactive telehealth cessation approaches within primary care have outsourced treatment to automated voice recognition systems,15 text messaging,13 and other services.12,14 Yet, no studies to our knowledge have systematically evaluated automated evidence-based cessation treatment delivery from a smoker's own PCP. Delivering treatment from a smoker's PCP affords the unique ability to capitalize upon the trust between smokers and their PCPs,16 which is predictive of greater adherence to care.17

An ideal PCP-delivered treatment to pair with universal identification of smoking status afforded through EHR data must be (1) evidence based and (2) scalable. An electronic visit (e-visit), which can be delivered automatically through the EHR, could be a pragmatic telehealth solution to universally and proactively deliver cessation treatment to smokers through primary care. E-visits are embedded in the most common EHRs and offer a secure platform through which patients can remotely engage with providers who in turn can deliver personalized treatment. Asynchronous e-visits eliminate in-session time constraints, enable PCPs to respond at a time that is suitable for them, and facilitate tailored treatment delivery to large numbers of patients.18,19 E-visit invitations can be automated and sent in bulk through the EHR to all patients who meet treatment criteria. After accepting an e-visit invitation, the patient completes a questionnaire that may include built-in algorithms to facilitate treatment decision making. All e-visit outcomes are sent to the PCP (or another medical team member) through the EHR. Upon reviewing the e-visit, the PCP will recommend a treatment plan. If medications are indicated, the PCP can e-prescribe the medication to the patient's pharmacy. Prior studies of asynchronous e-visits through primary care have found high satisfaction among both patients and PCPs and that such e-visits can be delivered efficiently (average time for patient completion = 8.3 min, average time for PCP to review and respond = 3.6 min).20

The purpose of this study was to develop and preliminarily evaluate an asynchronous smoking cessation e-visit that could be delivered proactively to adult smokers treated within the primary care environment. The goal of the e-visit is to automate delivery of the 5As to ensure that all primary care patients who smoke receive evidence-based cessation treatment. As such, the aims of this study were twofold: (1) to examine acceptability, feasibility, and treatment metrics associated with e-visit utilization and (2) to preliminarily examine the efficacy of the smoking cessation e-visit relative to treatment as usual (TAU) within primary care.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from Department of Family Medicine (DFM) practices affiliated with the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) between November 2018 and October 2019. Epic is the EHR system used institution-wide at MUSC. Within Epic, a study recruitment report was generated for all patients meeting the following criteria: (1) age 18+, (2) seen at a DFM practice in the past year, (3) current smoker as denoted within the health record, and (4) have access to MyChart, Epic's patient portal.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the MUSC IRB. Through MyChart, 817 patients included in the study recruitment report were sent an invitation and link to preliminary screening. Patients were deemed eligible for the study if during the initial screening they met the following criteria: (1) current cigarette smoking, defined as smoking at least five cigarettes per day for at least 20 out of the preceding 30 days, for at least the past 6 months, (2) possess a valid e-mail address that is checked daily to access follow-up assessments and MyChart messages, and (3) fluent in English. In total, 95 patients completed study screening and 75 were study eligible after screening.

Patients who completed study screening and were eligible were subsequently scheduled for a time to complete informed consent remotely with a member of the study team. Consent was completed either electronically or through mail, in both cases paired with a discussion with a member of the research team. After completion of informed consent, enrolled study participants completed baseline assessments through REDCap and then were randomized 2:1 to receive either the smoking cessation e-visit or TAU. All study participants were invited to complete follow-up research assessments at 1 and 3 months after their baseline assessments. Participants were compensated $20 in Amazon gift codes for completion of each study assessment and received a $20 bonus if all three assessments were completed. Participants randomized to the e-visit condition were not separately compensated for completion of the e-visits.

Interventions

Smoking cessation e-visit

Participants randomized to the e-visit condition were automatically linked to initiate an asynchronous cessation e-visit through MyChart. The initial baseline e-visit gathers information about smoking history and motivation to quit smoking, followed by an algorithm to determine the best U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cessation medication (i.e., nicotine replacement therapy [NRT], varenicline, or bupropion) to recommend to the patient. This algorithm is based on prior research21,22 and evidence-based guidelines.2 It uses branching logic to prioritize the most efficacious medications (varenicline and combination NRT), while tailoring recommendations based on contraindications and patient preference. The medication recommendation is then displayed to the patient with a personalized rationale, to which the patient can agree or request a different treatment. E-visit results then are sent to the provider's electronic in-basket, who then reviews the e-visit, responds to the patient through MyChart with instructions, and e-prescribes (if indicated) medication. All medications within this study were prescribed on label by two study physicians and were sent to the patient's pharmacy of record within their health record. Medication costs were not covered by the study.

All participants randomized to the e-visit condition are also invited to complete a follow-up e-visit 1 month after completion of the baseline e-visit. The purpose of the 1-month follow-up e-visit is to clinically assess progress toward cessation and troubleshoot barriers. This e-visit begins by assessing current smoking status, quit attempts within the past month, and quit duration. Subsequently, participants report (1) whether they received a cessation medication after baseline, (2) whether they are currently taking the medication, and (3) whether they have any questions/concerns about the medication. Participants are asked if they are interested in any other treatment options, including a medication refill. Results were sent to providers and reviewed and responded to in the same manner as the baseline e-visit.

Treatment as usual

The TAU condition was designed to mimic existing standard cessation practices. Participants randomized to the TAU condition were provided with information on the state quitline and a recommendation to contact their PCP to schedule a medical visit to discuss quitting smoking.

Measures

All participants at baseline completed a general assessment of demographics, including age, gender, race, educational attainment, annual household income, health insurance status, health history, and history with their primary care practice. Primary outcomes for this trial include measures related to (1) e-visit acceptability, feasibility, and treatment metrics, and (2) smoking cessation outcomes.

e-Visit acceptability, feasibility, and treatment metrics

To assess participant perception of the e-visit, during the 1-month research assessment, participants randomized to the e-visit condition completed a seven-item questionnaire in which they responded to the following items: (1) I found the e-visit easy to use, (2) I would use an e-visit again in the future, (3) I have experienced benefits from the e-visit, (4) during my e-visit, I felt I could trust my provider with my medical care, (5) I would recommend e-visits to other people, (6) it was as easy for me to state my concerns and ask questions through the e-visit as it would be for an in-person doctor visit, and (7) the e-visit was as good as an in-person visit with my doctor. Response options included strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree. Also during the 1-month research assessment, participants self-reported whether a smoking cessation medication recommendation or prescription was provided to them as a result of the baseline e-visit. If they responded that a medication recommendation or prescription was provided, they were queried as to whether they received that medication and, if they did not, why.

Additional indicators of e-visit feasibility and treatment metrics were captured through chart reviews from the EHR. These metrics included (1) whether the patient opted for the medication recommended by the e-visit, (2) whether the physician prescribed the medication recommended by the e-visit, (3) whether the participant completed the 1-month follow-up e-visit, and (4) time to complete the 1-month follow-up e-visit among those who completed it.

Smoking cessation outcomes

All participants at baseline were queried for number of cigarettes smoked per smoking day, incidence of quit attempts within the past year, and motivation to quit and confidence in quitting in the next month. Motivation and confidence were assessed through contemplation ladders23 scored 0–10 with 0 meaning not at all motivated/confident and 10 meaning extremely motivated/confident. During the 1- and 3-month research assessments, all participants self-reported the following: (1) number of cigarettes smoked per day for the past 7 days (also captured at baseline), (2) incidence of quit attempts since the prior study assessment, and (3) use of an FDA-approved smoking cessation medication since the last study assessment. Data regarding cigarettes smoked per day during the past week were coded as to whether the participant had reduced their average cigarettes per day by at least 50% between baseline and each follow-up. Participants who reported smoking zero cigarettes for the past 7 days were coded as having 7-day point prevalence abstinence. Those who reported making at least one quit attempt were subsequently queried for the duration of the longest quit attempt made since the last follow-up assessment. This information was then coded as (1) incidence of any quit attempt lasting at least 24 h and (2) floating abstinence, that is, any 7-day period of abstinence.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Chi-square and analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses were used to determine baseline differences in participant demographics as a function of treatment group as well as retention across follow-up assessments as a function of group. Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine e-visit acceptability, feasibility, and treatment metrics. Binary logistic regressions were utilized to examine differences in cessation outcomes as a function of treatment group at the 1- and 3-month timepoints. Given the pilot nature of this trial, completer analyses were utilized for cessation outcomes such that the total sample size at each follow-up assessment included only those who completed the assessment.

Results

Participant Characteristics

As this was a pilot trial, we sought a modest sample size that would still provide rich acceptability and preliminary efficacy data to inform future trials. In total, 51 participants were enrolled in the trial (n = 34 e-visit, n = 17 TAU). See Table 1 for participant demographics for the full sample as well as by treatment group. There were no significant demographic differences between groups. At baseline, participants on average reported smoking 14.65 (standard deviation [SD] = 9.18) cigarettes per smoking day. The majority of participants (56.86%) had made an attempt to quit smoking within the past year and motivation to quit (mean [SD] = 7.65 [2.64]) and confidence in quitting (6.06 [2.82]) within the next month were both on average high across participants. Most participants (92.16%) were insured and the most common insurance type was employer provided health insurance (45.10%). In terms of health history, nearly half of the sample (45.10%) reported being diagnosed by a doctor with depression and a similar number of participants reported hypertension (47.06%). Most participants (78.43%) had been receiving treatment from their primary care practice for longer than a year and had had three or fewer visits within the past year (72.55%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| FULL SAMPLE (n = 51) | ELECTRONIC VISIT (n = 34) | TREATMENT AS USUAL (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [M (SD)] in years | 46.39 (12.88) | 48.21 (13.42) | 42.76 (11.22) |

| Gender (% female) | 35 (68.63) | 23 (67.65) | 12 (70.59) |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 30 (58.82) | 22 (64.71) | 8 (47.06) |

| Black | 17 (33.33) | 11 (32.35) | 6 (35.29) |

| Other | 4 (7.84) | 1 (2.94) | 3 (17.65) |

| Education (%) | |||

| <High school diploma | 10 (19.61) | 7 (20.59) | 3 (17.65) |

| >High school diploma | 41 (80.39) | 27 (79.41) | 14 (82.35) |

| Annual household income (%) | |||

| <$50k | 27 (52.94) | 19 (55.88) | 8 (47.06) |

| >$50k | 24 (47.06) | 15 (44.12) | 9 (52.94) |

| Health insurance status (% insured) | 47 (92.16) | 31 (91.18) | 16 (94.12) |

| Medicaid | 13 (25.49) | 8 (23.53) | 5 (29.41) |

| Medicare | 8 (15.69) | 6 (17.65) | 2 (11.76) |

| Employer provided | 23 (45.10) | 15 (44.12) | 8 (47.06) |

| Other | 3 (5.88) | 2 (5.88) | 1 (5.88) |

| Baseline cigarettes per day [M (SD)] | 14.65 (9.18) | 15.38 (10.19) | 13.18 (6.78) |

| Quit attempt in the past year (% yes) | 29 (56.86) | 19 (55.88) | 10 (58.82) |

| Motivation to quit in the next month [M (SD)] | 7.65 (2.64) | 8.03 (2.34) | 6.88 (3.10) |

| Confidence in quitting in the next month [M (SD)] | 6.06 (2.82) | 6.32 (2.87) | 5.53 (2.72) |

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

Study retention was generally high across both 1-month (88.24%) and 3-month (76.47%) assessments. However, retention was lower among those randomized to the e-visit condition at both 1-month (TAU: 100%, e-visit: 82.35%; χ2 (1, 51) = 3.40, p = 0.07) and 3-month follow-ups (TAU: 94.12%, e-visit: 67.65%; χ2 (1, 51) = 4.41, p = 0.04).

E-Visit Acceptability, Uptake, and Outcomes

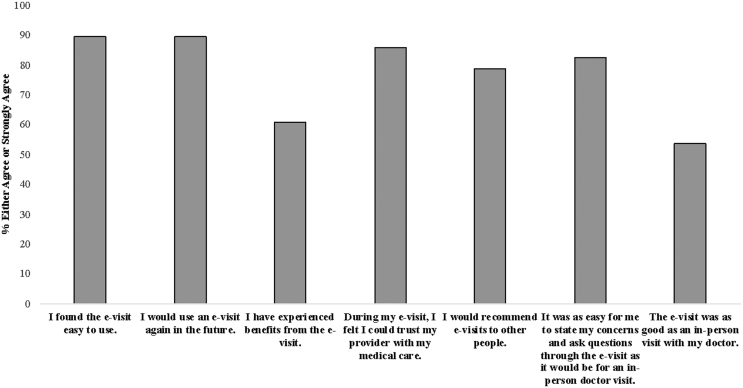

All participants randomized to the e-visit condition completed the baseline e-visit. Participant feedback after completion of the baseline e-visit was positive and results are presented in Figure 1. The most common treatment recommendation as a result of the e-visit was varenicline (70.59%), followed by combination NRT (i.e., patch+gum or lozenge; 17.6%), NRT patch (5.9%), NRT lozenge (2.9%), and counseling only (i.e., no medication recommended; 2.9%). Participants opted for the treatment recommended by the e-visit 79.41% of the time. For instances in which the participant did not opt for the treatment recommended by the e-visit (n = 7), the most common occurrence was that the e-visit recommended varenicline and the participant requested an alternate treatment (i.e., NRT, bupropion, or counseling only; n = 4). Physicians prescribed the treatment recommended by the e-visit 79.41% of the time. For instances in which the physician did not prescribe the treatment recommended by the e-visit, in five of these cases the participant opted for a treatment that differed from what was suggested by the e-visit and the physician abided by this requested. In the remaining two cases, the e-visit recommended varenicline and the physician prescribed NRT patch instead due to possible contraindications (n = 1) or did not prescribe a medication (n = 1). At the 1-month follow-up research assessment, participants were queried as to whether they received the medication recommended as a result of the baseline e-visit. Most participants (68.00%) who received a prescription reported receiving the medication from their pharmacy. The most common reason for not receiving medication among those who received a prescription was worry about the cost of the medication.

Fig. 1.

E-visit feedback. Feedback regarding the baseline e-visit was collected during the 1-month research follow-up. Respondents include n = 28 participants randomized to the e-visit condition who completed the 1-month research follow-up. e-visit, electronic visit.

Among participants randomized to the e-visit condition who completed the 1-month follow-up e-visit (55.88%), average time to completion was 1.42 (2.27) days after the e-visit invitation was sent. The most often (52.63%) outcome of the 1-month e-visit was prescription of the same medication prescribed after the baseline e-visit (i.e., a refill). In remaining cases, the participant was either prescribed a different medication (36.84%) or was not prescribed a medication (10.53%).

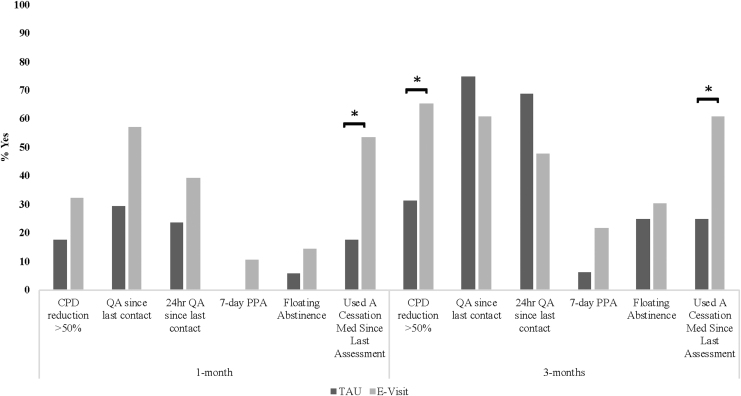

Smoking Cessation Outcomes

In general, smoking cessation outcomes favored the e-visit condition at both 1 and 3 months (Fig. 2). At 1 month, all cessation outcomes favored the e-visit condition (odds ratios [ORs]: 2.10–5.39). At 3 months, all cessation outcomes except for quit attempts favored the e-visit condition (ORs: 1.31–4.67). Regarding significant effects, as compared to TAU participants, e-visit participants were 5.39 times more likely to have used a cessation medication at 1 month (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.26, 22.99, p = 0.02) and 4.67 times more likely to have used a cessation medication at 3 months (95% CI 1.14, 19.07, p = 0.03). At 3 months, e-visit as compared with TAU participants were 4.13 times more likely to have reduced their cigarettes per day by at least 50% (95% CI 1.06, 16.10, p = 0.04).

Fig. 2.

Cessation outcomes as a function of treatment group. *p < 0.05. CPD, cigarettes per day; PPA, point prevalence abstinence; QA, quit attempt.

Discussion

These results preliminarily indicate feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the proactive, asynchronous smoking cessation e-visit. Across a number of indices, the intervention was both acceptable and feasible. Feedback from participants who completed the e-visit indicated high satisfaction as well as interest in using e-visits again in the future. Outcomes data captured through the EHR indicated that nearly all e-visits resulted in prescription of an FDA-approved smoking cessation medication. As such, this e-visit could have the potential to improve access to smoking cessation medications among adult smokers. This is a critical issue as only 36% of adult smokers who have been treated by a health professional within the past year report receiving a smoking cessation medication during that interaction.9 Use of a cessation medication can more than double a smoker's chances of successfully quitting.2 Thus, the key potential benefit of the smoking cessation e-visit is in extension of reach of evidence-based smoking cessation treatments, including FDA-approved medications. If scaled across primary care clinics and health care settings, a low-burden proactive cessation intervention such as we developed has the potential to increase utilization of cessation medications among smokers attempting to quit and ultimately improve cessation rates.

This study also revealed areas in which the e-visit could be modified to improve outcomes. Regarding modifications to the proactive treatment engagement approach, the majority of completed study screenings (78.9%) were completed by study eligible participants, suggesting that data available in the EHR can be utilized to identify the appropriate target population for a smoking cessation intervention. However, only 11.6% of study invitations resulted in completed screenings. Although this response rate is consistent with other published studies that proactively engage patients leveraging data available in the EHR,24,25 approaches should be considered to improve response rates to proactive telehealth approaches. Such approaches may include incentivizing patients for treatment engagement, adding additional personalization to outreach messages, and/or expanding the avenues through which proactive telehealth treatment is offered (e.g., through MyChart, e-mail, text message, and mail). Regarding possible modifications to the e-visit itself, 56% of participants randomized to the e-visit condition completed the 1-month follow-up e-visit. Although this is still an improvement upon published data, which suggest that only 6–10% of smokers receive follow-up focused on cessation treatment from their physician,6,9 there is likely room for further improvement to increase response rate to the follow-up e-visits. Similarly, 32% of participants who received a medication prescription did not receive the cessation medication, with the most common reason for nonreceipt being concerns about medication costs. To substantially improve access to evidence-based cessation treatment, the e-visit could be paired with existing channels for free receipt of medications (e.g., through state quitlines) to reduce cost-related barriers. Similarly, health care systems that adopt the e-visit approach could consider providing cessation medications for free to smokers who are either uninsured, underinsured, or whose insurance does not cover cessation treatment.

Although this pilot trial was designed primarily to examine feasibility and acceptability of the e-visit, cessation outcomes were secondarily examined and were also promising. Across most cessation indices, the e-visit outperformed TAU and with reasonable effect sizes. If replicated in a larger fully powered trial, these results would suggest that the e-visit could both improve treatment access and cessation outcomes relative to primary care standard care.

Results of this study should be interpreted with limitations in mind. First, completion of follow-up research assessments differed as a function of treatment group, with participants randomized to TAU more likely to complete follow-up assessments. The reason for this group difference is unclear, but in light of positive feedback from e-visit participants regarding the e-visit, it seems unlikely that randomization to the e-visit condition caused disengagement with the research study. Second, cessation outcomes for this pilot trial were based on self-report and were not biochemically verified. Third, study participants were recruited from family medicine practices affiliated with MUSC. As such, results may not generalize to other clinical sites. Finally, the e-visit was developed for and tested within the Epic EHR. Results may not generalize to other EHR systems, particularly if the patient-facing portal considerably differs from MyChart.

There are a number of important future directions stemming from this initial pilot study. All e-visits completed within this study were reviewed and responded to by two study physicians who were part of the study team. As such, provider- and systems-level factors that could either promote or hinder e-visit uptake are unknown. A future trial designed to examine implementation factors as they pertain to this e-visit will be a critical next step before expanding the e-visit platform. In addition, this pilot trial was not designed to examine individual-level moderators of treatment effects, but in light of established disparities in smoking cessation treatment receipt as a function of race, education, socioeconomic status, and rurality,26–30 it will be important to examine whether this e-visit approach either widens or narrows these established disparities. In conclusion, these pilot data suggest that the proactive asynchronous smoking cessation e-visit may be a promising approach to extend the reach of evidence-based treatment through primary care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Biomedical Informatics Center at MUSC including Paul Powers, Melissa Habrat, and Buck Rogers who led technical development of the e-visit.

Disclosure Statement

J.D. is co-owner of Behavioral Activation Tech LLC, a small business that develops and evaluates mobile application-based treatments for depression and co-occurring disorders. M.J.C. has received consulting honoraria from Pfizer and from Frutarom, Inc.

Funding Information

Funding for this research was provided by the South Carolina Telehealth Alliance, the Health Resources and Services Administration (U66 RH31458), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23 DA045766). The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, in writing this report, or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker T, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, et al. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National ambulatory medical care survey and national health interview survey, United States, 2005–2009. Morb Mortal Weekly Rep 2012;61(Suppl):38–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Juster HR, Ortega-Peluso CA, Brown EM, et al. A media campaign to increase health care provider assistance for patients who smoke cigarettes. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen KA, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2010;51:199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S, et al. Primary care provider-delivered smoking cessation interventions and smoking cessation among participants in the National Lung Screening Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1509–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schnoll RA, Rukstalis M, Wileyto EP, Shields AE. Smoking cessation treatment by primary care physicians: An update and call for training. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kruger J, O'Halloran A, Rosenthal A. Assessment of compliance with US Public Health Service clinical practice guideline for tobacco by primary care physicians. Harm Reduct J 2015;12:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kruger J, O'Halloran A, Rosenthal AC, Babb SD, Fiore MC. Receipt of evidence-based brief cessation interventions by health professionals and use of cessation assisted treatments among current adult cigarette-only smokers: National Adult Tobacco Survey, 2009–2010. BMC Public Health 2016;16:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD008743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bailey SR, Heintzman JD, Marino M, et al. Smoking-cessation assistance: Before and after stage 1 meaningful use implementation. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:192–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:218–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCarthy DE, Adsit RT, Zehner ME, et al. Closed-loop electronic referral to SmokefreeTXT for smoking cessation support: A demonstration project in outpatient care. Transl Behav Med 2019:ibz072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richter KP, Shireman TI, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Comparative and cost effectiveness of telemedicine versus telephone counseling for smoking cessation. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahoney MC, Erwin DO, Twarozek AM, et al. Leveraging technology to promote smoking cessation in urban and rural primary care medical offices. Prev Med 2018;114:102–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nelms E, Wang L, Pennell M, et al. Trust in physicians among rural Medicaid-enrolled smokers. J Rural Health 2014;30:214–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee YY, Lin JL. The effects of trust in physician on self-efficacy, adherence and diabetes outcomes. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1060–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murray E, Burns J, See TS, Lai R, Nazareth I.. Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD004274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Jong CC, Ros WJ, Schrijvers G. The effects on health behavior and health outcomes of Internet-based asynchronous communication between health providers and patients with a chronic condition: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dixon RF, Rao L. Asynchronous virtual visits for the follow-up of chronic conditions. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:669–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cropsey KL, Jardin BF, Burkholder GA, Clark CB, Raper JL, Saag MS. An algorithm approach to determining smoking cessation treatment for persons living with HIV/AIDS: Results of a pilot trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69:291–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valera P, McClernon FJ, Burkholder G, et al. A pilot trial examining African American and white responses to algorithm-guided smoking cessation medication selection in persons living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1975–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol 1991;10:360–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rogers ES, Fu SS, Krebs P, et al. Proactive tobacco treatment for smokers using veterans administration mental health clinics. Am J Prev Med 2018;54:620–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krebs P, Sherman SE, Wilson H, et al. Text2Connect: A health system approach to engage tobacco users in quitline cessation services via text messaging. Transl Behav Med 2020;10:292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Browning KK, Ferketich AK, Salsberry PJ, Wewers ME. Socioeconomic disparity in provider-delivered assistance to quit smoking. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fu SS, Sherman SE, Yano EM, Van Ryn M, Lanto AB, Joseph AM. Ethnic disparities in the use of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation in an equal access health care system. Am J Health Promot 2005;20:108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, White MM, Emery SL, Messer K. A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health 2011;101:699–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Doogan NJ, Roberts ME, Wewers ME, et al. A growing geographic disparity: Rural and urban cigarette smoking trends in the United States. Prev Med 2017;104:79–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Kurti AN, et al. Rural tobacco use across the United States: How rural and urban areas differ, broken down by census regions and divisions. Health Place 2016;39:153–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]