Abstract

Introduction and Aims.

HIV and hepatitis C virus transmission among people who inject drugs (PWID) is fuelled by personal and environmental factors that vary by sex. We studied PWID in Mexico to identify sex differences in multilevel determinants of injection risk.

Design and Methods.

From 2011 to 2013, 734 PWID (female: 277, male: 457) were enrolled into an observational cohort study in Tijuana. Participants completed interviews on injection and sexual risks. Utilising baseline data, we conducted multiple generalised linear models stratified by sex to identify factors associated with injection risk scores (e.g. frequency of injection risk behaviours).

Results.

For both sexes, dificult access to sterile syringes was associated with elevated injection risk (b = 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.33), using syringes from a safe source (e.g. needle exchange programs) was associated with lower injection risk (b = 0.87, 95% CI 0.82–0.94), and for every one-unit increase in safe injection self-efficacy we observed a 20% decrease in injection risk (b = 0.80, 95% CI 0.76–0.84). Females had a higher safe injection self-efficacy score compared to males (median 2.83, interquartile range 2.2–3 vs. median 2.83, interquartile range 2–3; P = 0.01). Among females, incarceration (b = 1.22, 95% CI 1.09–1.36) and police confiscation of syringes in the past 6 months (b = 1.16, 95% CI 1.01–1.33) were associated with elevated injection risk. Among males, sex work (b = 1.16, 95% CI 1.04–1.30) and polysubstance use in the past 6 months (b = 1.22, 95% CI 1.13–1.31) were associated with elevated injection risk.

Discussion and Conclusions.

Interventions to reduce HIV and hepatitis C virus transmission among PWID in Tijuana should be sex-specific and consider multilevel determinants of injection risk to create safer drug use environments.

Keywords: people who inject drug, injection risk behaviour, sex difference, HIV and HCV transmission, Mexico

Introduction

Tijuana has one of the highest rates of illicit drug use consumption, and one of the largest populations of people who inject drugs (PWID) in Mexico [1–3]. The prevalence of HIV among PWID in Tijuana is approximately 17.5 times higher than that among the general population in Mexico (3.5% verses 0.2%) [4]. Further, 96% of PWID in Tijuana are living with hepatitis C (HCV) antibodies (anti-HCV) [5], which is nearly twice as high as the estimated prevalence of PWID living with anti-HCV worldwide (52.3%) [6]. The spread of HIV and HCV among PWID is driven by the dynamic interaction between personal and environmental factors [7,8].

In Tijuana, HIV and HCV risk among PWID is exacerbated by various environmental influences. Limited access to needle exchange programs (NEP) reduces access to sterile syringes, thereby increasing syringe sharing practices [9]. Police confiscation of syringes also increases HIV and HCV risk by reducing access to injection equipment [10]. Further, PWID’s participation in sex work is associated with sexual and injection risk behaviours which are driven by adverse sociostructural conditions (e.g. sexual violence and economic vulnerability) [11]. Additionally, the high rates of methamphetamine and heroin injection in this region, which are fuelled by Tijuana’s placement along a prominent drug trafficking route [1], are also associated with HIV and HCV infection via increased injection risk behaviours [12].

HIV prevalence among PWID in Mexico [13] and HCV incidence in several settings [14,15] tend to be significantly higher among female PWID compared to males. These disparities are driven by personal and environmental risk factors that vary by sex, such as stigma among female substance users [16], sexual violence [17], economic vulnerability [18], participation in sex work and reduced efficacy to engage in safer injection practices [19]. As such, drug use environments for male and female PWID are differentially shaped by several levels of HIV and HCV risk [16,19]. However, despite these known sex disparities, there is still a surprising lack of data disaggregated by sex among PWID globally, limiting our ability to uncover sex-related trends in the determinants of injection risk [16,20]. More research is needed to examine sex differences in the correlates of injection risk in order to inform intervention efforts for male and female PWID, especially in low-and middle-income countries such as Mexico.

To address this gap in research, we applied the social ecological model (SEM) and studied male and female PWID in Tijuana to identify sex differences in the personal and environmental factors associated with injection risk. We hypothesized that HIV and HCV risk factors (e.g. sex work, incarceration, police confiscation, homelessness and difficultly accessing sterile syringes) would differ by sex, such that females would experience greater barriers to practicing injection risk reduction compared to males. As such, this research will add to the body of literature on sex differences in the multilevel determinants of injection risk among PWID in Mexico, and may help inform the development of comprehensive sex-specific prevention packages for PWID in this region.

Methods

Theoretical framework

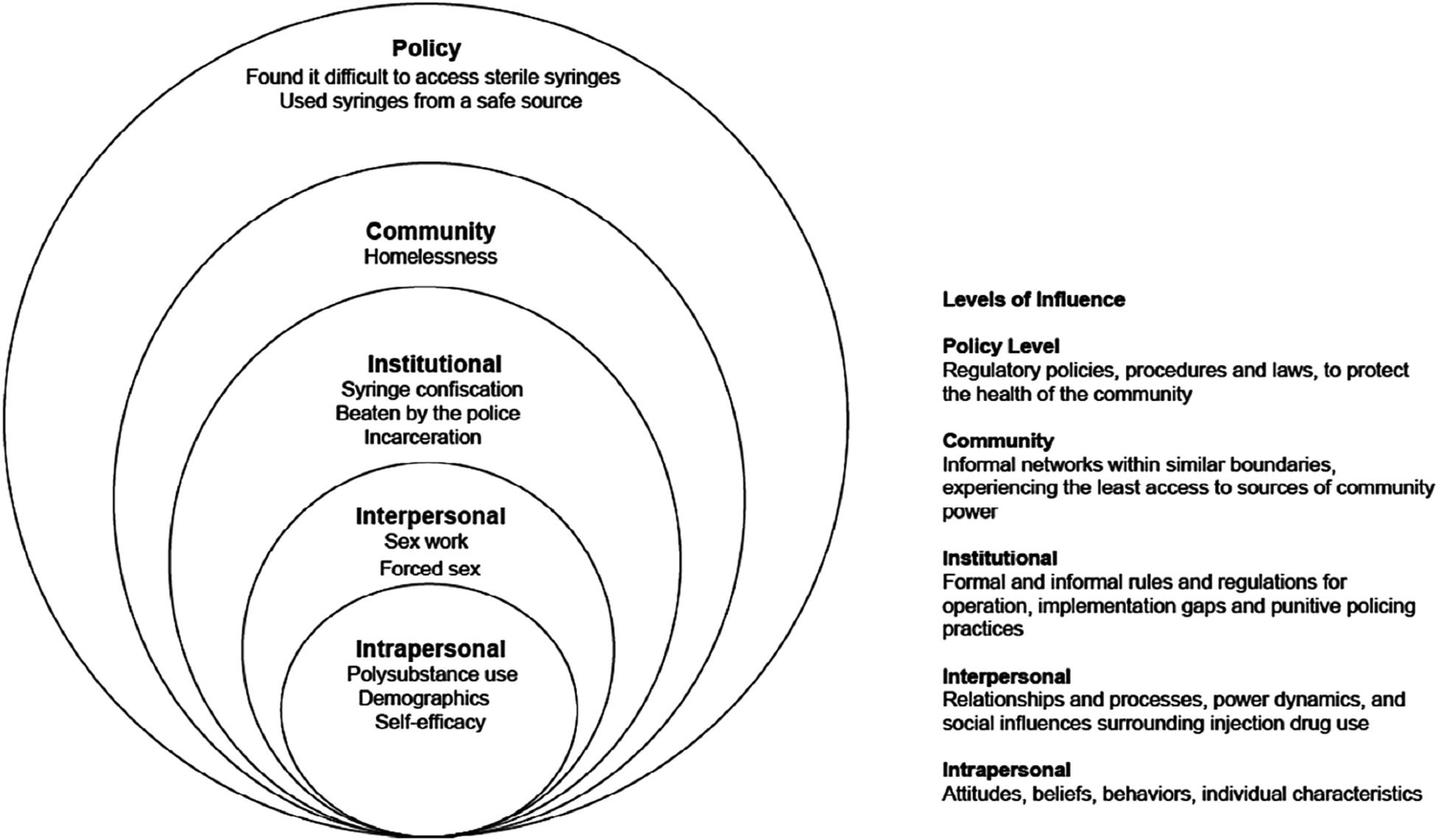

SEM is a widely accepted theoretical framework that considers how individuals and environments interact [8,21,22]. SEM recognises the following five levels of influence on human behaviour: intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy. Given the increasing recognition of various levels of HIV and HCV risk and the need to create multilevel prevention strategies, we used this framework to guide our research (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The social ecological model applied to understand the personal and environmental correlates of injection risk among males and females who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico.

Baseline data were drawn from ‘Proyecto El Cuete’ an ongoing prospective cohort study of PWID in Tijuana, Mexico. A detailed description of the study protocol has been published elsewhere [23]. All study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of California, San Diego and the University of Xochicalco in Tijuana. All participants provided written informed consent at baseline.

Recruitment, screening and enrolment

A total of 734 individuals were enrolled between 2011 and 2013. Participants were recruited using targeted sampling techniques (i.e. street-based outreach). Eligible participants were required to: (i) be at least 18 years old; (ii) self-report injection drug use in the past month; (iii) have visual evidence of injection drug use (e.g. track marks); (iv) be able to speak English or Spanish; (v) be able to provide written informed consent; (vi) have no plans to leave Tijuana for 24 months; and (vii) report no current participation in an intervention. All participants received US $5.00 for completing the screening process.

Baseline survey

Participants completed a baseline assessment that lasted approximately 90 min, and was administered by trained bilingual interviewers with extensive experience working with PWID in Mexico. To enhance the reliability and validity of self-reported sensitive behaviours (e.g. HIV risks), data were collected using computer-assisted participant interview software [24] and conducted in a private setting. Participants were compensated US $20.00 at baseline.

Measures

Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was an ‘injection risk score’, which was modelled closely after a composite variable created for the Drug User’s Intervention Trial [25], and has demonstrated strong predictive validity in prior research [26,27]. This score was calculated from an index of five Likert-scaled variables assessing the frequency of injection risk behaviours in the past 6 months. Response options include never, sometimes, about half of the time, often and always. These items were averaged to create an average injection risk score ranging from 1 to 5. Item five was reverse coded to ensure that higher values correspond to higher risk. This measure demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.72). The items in this measure include: (i) “Of the times you injected in the last six months, how often did you use a syringe that you knew or suspected that it had been used before by someone else?”; (ii) “Of the times you injected in the last six months, how often did you divide up drugs with somebody else by using a syringe?”; (iii) “Of the times you injected in the last six months, how often did you use a cooker, cotton, or water with someone or after someone else used it?”; (iv) “Of the times you injected in the last six months, how often did you buy drugs that came already prepared in a syringe?”; and (v) “Of the times you injected in the last six months, how often did you inject with a new, sterile syringe?”.

Intrapersonal level factors

Informed by the SEM [28], variables that represent beliefs, behaviours or individual characteristics were placed at the intrapersonal level: age in years, self-reported sex (female sex/male sex), number of years of education completed starting at first grade, marital status (married/common law marriage versus single/divorced/separated or widowed), monthly average income of at least 3500 Mexican pesos (yes/no), number of years lived in Tijuana, and the ability to speak English (yes/no). Participants were also asked to report their age at first injection, which was used to calculate the total number of years of injection drug use by subtracting each participant’s current age from the age they reported first injecting. Data were also collected on drugs injected at least twice a day or more in the past 6 months including methamphetamine, and methamphetamine and heroin together.

We considered ‘safe injection self-efficacy’ using a six-item index that has been tested and validated among PWID in the US [29]. Likert-scaled responses for this index include: absolutely sure I cannot, pretty sure I cannot, pretty sure I can and absolutely sure I can. These items were averaged to create an average safe injection self-efficacy score ranging from 1 to 4, with higher scores representing higher levels of self-efficacy. This measure demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). The items in this measure include: (i) “I can avoid injecting with a needle someone else has used, even if I am injecting with people I know well”; (ii) “I can avoid injecting with a needle someone else used even if I am dope sick or in withdrawal”; (iii) “I can avoid using cookers, cottons, or rinse water that someone else used, even if I am injecting with people I know well”; (iv) “I can avoid using my injecting partner’s needle, even if we have shared needles before”; (v) “I can avoid using my injecting partner’s cooker, cotton, or rinse water, even if we’ve shared them before”; and (vi) “I can avoid injecting with a needle someone else used, even if I have had sex without condoms with that person”.

Interpersonal level factors

Informed by the SEM [28], variables that represent relationships or power dynamics were placed at the interpersonal level. Sex work (yes/no) was defined as receiving something one needed (e.g. money, drugs, food) in exchange for sex in the past 6 months. Forced sex (yes/no) was defined as ever having been forced into having sex by someone using physical or emotional pressure.

Institutional level factors

Informed by the SEM [28], variables that represent formal or informal regulations or practices were placed at the institutional level: incarceration in the past 6 months (yes/no); police confiscation of syringes without arrest in the past 6 months (yes/no); and reporting ever being beaten by law enforcement (yes/no).

Community level factors

Informed by the SEM [28], variables that represent populations experiencing limited access to sources of community power were placed at the community level. Homelessness was defined as sleeping in places consistent with being homeless (e.g. abandoned buildings and/or on the street) in the past 6 months (yes/no).

Policy level factors

Informed by the SEM [28], variables that represent or serve as proxies for public health policies were placed at the policy level: used syringes from a ‘safe source’ (e.g. pharmacies, NEPs, hospitals or clinics) in the past 6 months (yes/no); and finding it difficult to access new/sterile syringes in the past 6 months (yes/no).

Statistical analyses

Using baseline data, we compared females and males with respect to factors in the SEM, using χ2 tests for dichotomous variables and depending on distributional assumptions T-tests or Wilcoxon Ranksum tests for continuous variables (Table 1). Then, simple generalised linear regression models with a lognormal distribution stratified by sex were used to identify factors associated with injection risk by sex. Each exposure in bivariate analyses (Table 2) with a P value ≤0.05 was explored further in adjusted analyses.

Table 1.

Intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community and policy level factors among females and males who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico (N = 734)

| Females (n = 277) n (%) | Males (n = 457) n (%) | P | Total (N = 734) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal level factors | ||||

| Average age (SD) | 35.1 (8.9) | 38.8 (8.7) | <0.001 | 37.4 (8.9) |

| Median age at first injection (IQR) | 15 (13–17) | 14 (12–16) | <0.001 | 14 (12–16) |

| Married or common-law marriage | 158 (57.0) | 175 (38.3) | <0.001 | 333 (45.4) |

| Median number of years of education since first grade (IQR) | 8 (6–11) | 8 (6–9) | 0.06 | 8 (6–10) |

| English speaking | 116 (41.9) | 173 (37.9) | 0.28 | 289 (39.4) |

| Earned at least 3500 Mexican pesos on average monthlyb | 90 (32.6) | 111 (24.5) | 0.02 | 201 (27.5) |

| Median number of years lived in Tijuana (IQR) | 10 (4.7–17.5) | 14.4 (8–21) | <0.001 | 12 (6–20) |

| Males reporting ever having sex with another male | - | 160 (35.24) | - | 160 (21.8) |

| Median number of years injecting drugs (IQR)c | 12 (5–20) | 18 (12–24) | <0.001 | 16 (9–22) |

| Methamphetamine and heroin co-injection ≥ twice a daya | 86 (31.1) | 171 (37.4) | 0.08 | 257 (35.0) |

| Methamphetamine injection ≥ twice a daya | 38 (13.7) | 58 (12.7) | 0.70 | 96 (13.1) |

| Median safe injection self-efficacy score (range 1–4) (IQR)d | 2.83 (2.2–3) | 2.83 (2–3) | 0.01 | 2.83 (2–3) |

| Median injection risk score (range 1–5) (IQR)e | 2.2 (1.6–3) | 2.2 (1.6–2.8) | 0.10 | 2.2 (1.6–2.8) |

| Injection risk indicators | ||||

| Syringe sharing ≥ half of the timea | 103 (37.2) | 145 (31.7) | 0.13 | 248 (33.8) |

| Syringe mediated drug sharingf ≥ half of the timea | 95 (34.4) | 172 (37.7) | 0.37 | 267 (36.5) |

| Injection equipment sharing ≥ half of the timea | 137 (49.6) | 218 (47.8) | 0.63 | 355 (48.5) |

| Bought drugs already prepared in a syringe ≥ half of the timea | 16 (5.8) | 26 (5.7) | 0.94 | 42 (5.8) |

| Used a sterile syringe for each injection ≥ half of the timea | 140 (50.9) | 227 (49.8) | 0.77 | 367 (50.2) |

| Interpersonal level factors | ||||

| Sex worka,g | 176 (65.7) | 49 (10.7) | <0.001 | 225 (31.0) |

| MSM who reported sex workh | - | 41.0 (9.0) | - | 41.0 (9.0) |

| Ever forced into having sexi | 99 (35.9) | 18 (3.9) | <0.001 | 117 (16.0) |

| Institutional level factors | ||||

| Incarcerationa | 83 (30.2) | 198 (43.3) | <0.001 | 281 (38.4) |

| Syringe confiscation by policea | 37 (13.4) | 46 (10.1) | 0.17 | 83 (11.3) |

| Ever beaten by the police | 62 (22.5) | 296 (64.8) | <0.001 | 358 (48.8) |

| Community level factors | ||||

| Homelessnessa,j | 92 (33.2) | 107 (23.4) | <0.01 | 199 (27.1) |

| Policy level factors | ||||

| Used syringes from a safe sourcea,k | 96 (34.7) | 237 (51.9) | <0.001 | 333 (45.4) |

| Found it hard to access new or sterile syringesa | 49 (17.7) | 87 (19.1) | 0.63 | 136 (18.6) |

Past 6 months.

Average monthly income of 3500 Mexican pesos which is approximately US$182.

Number of years injecting drugs was calculated by taking the participant’s current age and subtracting it from the age they reported first injecting drugs.

Self-efficacy for safer injection practices score was created from six items assessing one’s efficacy to engage in safer injection practices.

The injection risk score: was created from five index variables assessing: how often people who inject drugs reported syringe sharing, syringe mediated drug sharing, equipment sharing, buying drugs that came prepared in a syringe, and injecting with a new/sterile syringe, in the past 6 months.

Syringe-mediated drug sharing is where syringes are used to divide and share drugs.

Sex work includes those who reported selling sex in exchange for money, drugs, food, shelter or transportation in the past 6 months.

MSM who reported sex work includes men who reported ever having sex with another male and sex work in the past 6 months.

Forced sex was defined as ever having been forced into having sex by someone using physical or emotional pressure.

Homelessness includes those who slept in places mostly consistent with being homeless, including abandoned buildings and outdoors/on the street, in the past 6 months.

Used syringes from a safe source: pharmacy, needle exchange program, doctor, hospital or clinic in the past 6 months. P-values were derived from χ2 tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and T-tests depending on distributional patterns.

Some percentages are based on denominators smaller than the n listed in the column heading this is due to missing data. IQR, interquartile range.

IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Simple generalised linear model results of the personal and environmental correlates of injection risk behaviours among females and males who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico (N = 734)

| Females (n = 277) | Males (n = 457) | Overall (N = 734) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P | |

| Intrapersonal level factors | |||||||||

| Methamphetamine and heroin | 1.06 | 0.97–1.17 | 0.191 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.23 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.05–1.17 | <0.001 |

| co-injectiona | |||||||||

| Methamphetamine injection ≥a | 0.95 | 0.83–1.08 | 0.405 | 1.08 | 0.97–1.20 | 0.162 | 1.03 | 0.94–1.11 | 0.542 |

| Self-efficacy for safer injection | 0.79 | 0.75–0.83 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.74–0.82 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.75–0.81 | <0.001 |

| practicesb | |||||||||

| Interpersonal level factors | |||||||||

| Sex workc,d | 1.14 | 1.03–1.25 | 0.012 | 1.26 | 1.16–1.38 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.10–1.22 | <0.001 |

| Ever forced into having sexe | 1.06 | 0.97–1.16 | 0.23 | 1.16 | 0.95–1.41 | 0.14 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.18 | 0.01 |

| Institutional level factors | |||||||||

| Incarcerationc | 1.21 | 1.10–1.32 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.11–1.26 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.12–1.24 | <0.001 |

| Syringe confiscation by the policec | 1.14 | 1.02–1.28 | 0.021 | 1.25 | 1.13–1.38 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 1.12–1.30 | <0.001 |

| Ever beaten by the policec | 1.06 | 0.95–1.19 | 0.237 | 1.07 | 0.99–1.15 | 0.067 | 1.03 | 0.97–1.09 | 0.235 |

| Community level factors | |||||||||

| Homelessnessc | 0.97 | 0.88–1.06 | 0.559 | 1.06 | 0.98–1.14 | 0.133 | 1.03 | 0.96–1.09 | 0.399 |

| Policy level factors | |||||||||

| Used syringes from a safe sourcec,f | 0.86 | 0.79–0.95 | 0.002 | 0.83 | 0.77–0.88 | <0.001 | 0.84 | 0.79–0.88 | <0.001 |

| Found it hard to access new/sterile | 1.38 | 1.26–1.50 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 1.13–1.31 | <0.001 | 1.27 | 1.20–1.35 | <0.001 |

| syringesc | |||||||||

At least twice a day in the past 6 months.

Self-efficacy for safer injection practices score was created from six items assessing one’s efficacy to engage in safer injection practices.

Past 6 months.

Sex work includes those who reported selling sex in exchange for money, drugs, food, shelter or transportation in the past 6 months.

Forced sex was defined as every having been forced into having sex by someone using physical or emotional pressure.

Used needles from a safe source includes pharmacies, needle exchange programs, hospitals or clinics in the past 6 months. Unadjusted estimates listed here represent the total effect of each exposure on average injection risk scores by sex and overall. All beta coefficients were exponentiated to facilitate interpretation. CI, confidence interval.

Multiple generalised linear regression models with a lognormal distribution stratified by sex were performed to estimate the association of statistically significant exposures from bivariate models with injection risk scores by sex, while controlling for identified confounders (Table 3). We controlled for the following factors that have been identified as correlates of injection risk among PWID in Tijuana [13]: age, education, income and length of residence in Tijuana. In order to avoid committing a “table two fallacy” [30,31], all primary exposures were estimated in separate models, and secondary effects were not interpreted. A “table two fallacy” is where one adjusts for primary effect measures and mistakenly reports and interprets these coefficients as total effects instead of controlled direct effects [30]. All beta coefficients were exponentiated to facilitate the interpretation of our results. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2.

Table 3.

Multiple generalised linear model results of the personal and environmental correlates of injection risk behaviours among females and males who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico (N = 734)

| Females (n = 277) | Males (n = 457) | Overall (N = 734) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P | β | 95% CI | P | |

| Intrapersonal level factors | |||||||||

| Methamphetamine and heroin | 1.05 | 0.94–1.17 | 0.378 | 1.22 | 1.13–1.31 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 1.08–1.23 | <0.001 |

| co-injection ≥ twice a daya | |||||||||

| Self-efficacy for safer injectionb | 0.78 | 0.72–0.83 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.77–0.88 | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.76–0.84 | <0.001 |

| Interpersonal level factors | |||||||||

| Sex workc | 1.10 | 0.96–1.25 | 0.169 | 1.16 | 1.04–1.30 | 0.008 | 1.14 | 1.04–1.24 | 0.004 |

| Ever forced into having sexd | 1.03 | 0.92–1.16 | 0.60 | 1.17 | 0.95–1.43 | 0.14 | 1.05 | 0.95–1.17 | 0.33 |

| Institutional level factors | |||||||||

| Incarcerationa | 1.22 | 1.09–1.36 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.17 | 0.057 | 1.14 | 1.06–1.22 | <0.001 |

| Syringe confiscation by the policea | 1.16 | 1.01–1.33 | 0.039 | 1.04 | 0.90–1.21 | 0.558 | 1.09 | 0.99–1.21 | 0.086 |

| Policy level factors | |||||||||

| Used syringes from a safe sourcea,e | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 | 0.003 | 0.90 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.014 | 0.87 | 0.82–0.94 | <0.001 |

| Found it hard to access new/sterile | 1.34 | 1.21–1.48 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.06–1.29 | 0.002 | 1.24 | 1.16–1.33 | <0.001 |

| syringesa | |||||||||

Past 6 months.

Self-efficacy for safer injection practices score was created from six items assessing one’s efficacy to engage in safer injection practices.

Sex work includes those who reported selling sex in exchange for money, drugs, food, shelter or transportation in the past 6 months.

Forced sex was defined as ever having been forced into having sex by someone using physical or emotional pressure.

Used needles from a safe source includes pharmacies, needle exchange programs, hospitals or clinics in the past 6 months. Each stratified model controlled for age, education, income, and length of residence in Tijuana, Mexico.

Models estimating overall effects controlled for the aforementioned confounders in addition to sex.

Adjusted estimates listed here represent the total effect of each exposure on average injection risk scores by sex and overall.

All beta coefficients were exponentiated to facilitate interpretation.

CI, confidence interval.

Results

Of 734 PWID, 277 (37.7%) were female and 457 (62.3%) were male. The average age was 37.4 (SD=8.9), and the median age at first injection was 14 [interquartile range (IQR)=12.0–16.0]. Over a third (39.4%) of the sample reported being able to speak English. One-fifth of males (21.8%) reported ever having sex with another male (Table 1).

Intrapersonal level differences by sex

As shown in Table 1, baseline comparisons of female and male PWID suggested that the two groups differed with respect to some intrapersonal level factors. Females were significantly younger compared to males [35.1 (SD=8.9), vs. 38.8 (SD=8.7), P < 0.001], and initiated injection drug use at a significantly older age compared to males [median 15 (IQR=13.0–17.0) vs. 14 (IQR=12.0–16.0)]. Males reported living in Tijuana for significantly longer durations compared to females [median 14.4 (IQR= 8.0–21.0) vs. median = 10 (IQR=4.7–17.5), P < 0.001]. A higher proportion of females reported earning ≥$3500 Mexican pesos on average each month compared to males (32.6% vs. 24.5%, P = 0.02). A significantly higher proportion of females reported being married compared to males (57.0% vs. 38.3%, P < 0.001). Males reported a higher median number of years injecting drugs compared to females [18 (IQR=12.0–24.0) vs. 12 (IQR=5.0–20.0), P < 0.001]. Finally, females reported a higher median score for safe injection self-efficacy compared to males [2.8 (IQR=2.2–3.0) vs. 2.8 (2.0–3.0), P = 0.01].

Interpersonal level differences by sex

Compared to males, a significantly greater proportion of females reported engaging in sex work in the past 6 months (65.7% vs. 10.7%, P < 0.001), and reported ever being forced into having sex (35.9% vs. 3.9%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Institutional level differences by sex

A greater proportion of males reported incarceration in the past 6 months compared to females (43.3% vs. 30.2%, P < 0.001), and a significantly greater proportion of males reported ever being beaten by the police compared to females (64.8% vs. 22.5%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Community level differences by sex

Females were significantly more likely to report being homeless in the past 6 months compared to males (33.2% vs. 23.4%, P < 0.01) (Table 1).

Policy level differences by sex

A significantly greater proportion of males reported using syringes from a ‘safe source’ compared to females (51.9% vs. 34.7%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

In adjusted analyses (Table 3), among both sexes, finding it difficult to access sterile syringes was associated with a 24% increase in average injection risk scores (b = 1.24, 95% CI 1.16–1.33). Using syringes from a ‘safe source’ was associated with a 13% decrease in average injection risk scores (b = 0.87, 95% CI 0.82–0.94). Similarly, for every one-unit increase in safe injection self-efficacy we observed a 20% decrease in average injection risk scores (b = 0.80, 95% CI 0.76–0.84).

Among females, incarceration and police confiscation of syringes in the past 6 months were associated with a 22% (b = 1.22, 95% CI 1.09–1.36) and a 16% increase in average injection risk scores (b = 1.16, 95% CI 1.01–1.33), respectively. Among males, sex work and injecting methamphetamine and heroin together ≥ twice a day in the past 6 months were associated with a 16% (b = 1.16, 95% CI 1.04–1.30) and a 22% increase in average injection risk scores (b = 1.22, 95% CI 1.13–1.31), respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study examining sex differences in the determinants of injection risk among male and female PWID in Mexico identified several important findings. Among both sexes, safe injection self-efficacy and using syringes from a safe source were associated with lower injection risk. Conversely, finding it difficult to access sterile syringes was associated with elevated injection risk among both sexes. We also uncovered several risk factors that were independently associated with injection risk and varied by sex. Sex work and polysubstance use were associated with elevated injection risk among males only. Recent incarceration and police confiscation of syringes were associated with elevated injection risk among females only. Together, these findings may help inform the development of sex-specific interventions that seek to address the determinants of injection risk among PWID in Mexico.

The strong association between safe injection self-efficacy and lower injection risk has important implications for behavioural interventions that seek to reduce HIV and HCV transmission among PWID. According to former research, a sexual and injection risk reduction intervention increased safe injection self-efficacy which in turn decreased receptive needle sharing among female sex worker-PWID in the Mexico-US border region [32]. This suggests that safe injection self-efficacy can be enhanced through behavioural interventions. Based on our findings, we recommend that interventions aiming to reduce the spread of HIV and HCV among PWID utilise strategies to enhance safe injection self-efficacy. Our study adds to the body of literature on safe injection self-efficacy [25,32–34], by showing how it is associated with risk reduction for both male and female PWID in Tijuana. This is promising, as it suggests that safe injection self-efficacy may act as a buffer against injection risk behaviours for both sexes.

We also found that using syringes from a safe source was associated with lower injection risk and finding it difficult to access sterile syringes was associated with elevated injection risk. These findings underscore the importance of harm reduction programs in reducing injection risk by providing free access to sterile injection equipment, offering risk reduction counselling and providing referrals to health and social services [35–37]. Unfortunately, in February of 2013 the Global Fund for HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria withdrew support for NEPs in Mexico due to their rising gross domestic product [38]. Consequently, there are only two sanctioned NEPs in Tijuana serving an estimated 6000–10 000 PWID [39]. Based on our findings, we recommend reinstating funding for NEPs, in order to increase access to sterile injection equipment and facilitate connections to key health and social services for PWID in Tijuana [35].

Interestingly, we found that sex work was associated with an increase in injection risk among males only. One potential explanation for this finding is that the majority of males in our sample who reported sex work were also men who have sex with men (83.7%), and HIV and HCV prevention service coverage among men who have sex with men in Tijuana remains low, resulting in a missed opportunity to reduce drug and sex related risks [40,41]. Similarly, other studies among PWID in Canada and the US found independent associations between needle sharing and homosexual and bisexual orientation, which may have been due to the underreporting of sex work [42,43]. Our finding underscores the need to increase access to harm reduction services for this subpopulation of PWID in Tijuana, in order to reduce the excess risk associated with injection drug use.

This study also found that polysubstance use (i.e. methamphetamine and heroin co-injection) was associated with elevated injection risk among males only. Former research among PWID in Estonia and Russia found that opiate and stimulant co-injection was associated with injection and sexual risk behaviours, but no differences by sex were reported [44]. Similarly, research among PWID in Tijuana found that polydrug use was independently associated with HIV risk, but no differences by sex were found [12,45]. Findings from our study add to this body of literature [12,44,45] by demonstrating sex differences in the relationship between polysubstance use and injection risk. Future interventions in Tijuana should scale-up access to medication-assisted treatments for opioid use disorder [46], develop pharmacotherapies for stimulant use disorder [47] and consider delivering medication treatments in conjunction with proven behavioural therapies [48].

In our study, recent incarceration was associated with elevated injection risk for females only. In Latin America, the number of women incarcerated nearly doubled between 2006 and 2011 when recruitment for this study began, and the vast majority (60–80%) of these women were incarcerated for nonviolent drug-related crimes [49]. Incarceration has been shown to increase HIV and HCV risk among PWID in several settings [50,51], but these studies reported no evidence that the impact of incarceration on injection risk was greater among females compared to males. Findings from this study expand upon former research [50,51] by demonstrating that the impact of incarceration on injection risk is differentially associated with sex among PWID in Mexico.

The association between police confiscation of syringes and elevated injection risk among female PWID maps onto former research conducted among PWID in Mexico, which documented that such punitive policing practices increase syringe sharing [10,52–56]. In Mexico, syringe purchase and possession without a prescription is legal, therefore, this finding also highlights a significant implementation gap [54,55]. Our results support this previous work, suggesting that policing practices in Tijuana continue to exacerbate injection risk especially among female PWID. Interventions should enhance law enforcement’s knowledge of harm reduction, reduce stigma among female PWID, and ensure that policing practices are consistent with current drug policy and international guidelines [57].

Although this study provides important insight into the factors that differentially shape injection risk for male and female PWID in Mexico, our study has limitations. We used nonprobability sampling methods, which limits the generalisability of our findings to PWID in other settings. We used cross-sectional data, which limits our ability to disentangle temporal associations. Future research should examine whether the factors associated with injection risk predict behaviour change in longitudinal analyses. Baseline data were collected between 2011 and 2013 and may not represent current trends among PWID in Tijuana, which further limits the generalisability of our findings. Although the outcome measure for this study was modelled closely after a measure used in a large intervention trial designed to reduce sexual and injection risk among PWID [25], it has not been psychometrically validated. However, it is important to note that this measure has demonstrated strong predictive validity [26,27], and internal consistency. Responses on HIV-risk behaviours from female PWID may be subject to differential misclassification bias [58,59], which can arise from stigma among women who use drugs [16,60]. Finally, our measure of safe injection self-efficacy may not accurately capture the experiences of female PWID who rely on male partners for drug injection.

In summary, this study shows how personal and environmental factors contribute to injection risk and differ markedly by sex among PWID in Mexico. In doing so, this study highlights several key factors, which shape injection risk among male and female PWID. As such, findings from this study may help inform the development of comprehensive sex-specific interventions that address several levels of HIV and HCV risk.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions made by all of our study participants and research staff.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Bucardo J, Brouwer KC, Magis-Rodríguez C et al. Historical trends in the production and consumption of illicit drugs in Mexico: implications for the prevention of blood borne infections. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;79:281–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rodríguez CM, Marques LF, Touzé G. HIV and injection drug use in Latin America. AIDS 2002;16:S34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Brouwer KC, Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodríguez C et al. Estimated numbers of men and women infected with HIV/AIDS in Tijuana, Mexico. J Urban Health 2006;83:299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Strathdee SA. Proyecto el Cuete phase IV. NIDA grant R01 DA0 119829. 2010. Available at: https://profiles.ucsd.edu/steffanie.strathdee [Google Scholar]

- [5].White EF, Garfein RS, Brouwer KC et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and HIV infection among injection drug users in two Mexican cities bordering the US. Salud Publica Mex 2007;49:165–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1192–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rhodes T Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. Int J Drug Policy 2009;20:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 2013;13:482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pollini RA, Rosen PC, Gallardo M et al. Not sold here: limited access to legally available syringes at pharmacies in Tijuana, Mexico. Harm Reduct J 2011;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Beletsky L, Lozada R, Gaines T et al. Syringe confiscation as an HIV risk factor: the public health implications of arbitrary policing in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez. Mexico J Urban Health 2013;90:284–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Strathdee SA, Philbin MM, Semple SJ et al. Correlates of injection drug use among female sex workers in two Mexico–US border cities. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008;92:132–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Meacham MC, Rudolph AE, Strathdee SA et al. Polydrug use and HIV risk among people who inject heroin in Tijuana, Mexico: a latent class analysis. Subst Use Misuse 2015;50:1351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Ojeda VD et al. Differential effects of migration and deportation on HIV infection among male and female injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. PLoS One Grinsztejn B, editor 2008;3:e2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Esmaeili A, Mirzazadeh A, Carter GM et al. Higher incidence of HCV in females compared to males who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:117–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Esmaeili A, Mirzazadeh A, Morris MD et al. The effect of female sex on hepatitis C incidence among people who inject drugs: results from the international multicohort InC3 collaborative. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:20–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer JP, Modi SN, Arasteh K, Hagan H. Are females who inject drugs at higher risk for HIV infection than males who inject drugs: an international systematic review of high seroprevalence areas. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;124:95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Braitstein P, Li K, Tyndall M et al. Sexual violence among a cohort of injection drug users. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bucardo J, Semple SJ, Fraga-Vallejo M, Davila W, Patterson TL. A qualitative exploration of female sex work in Tijuana, Mexico. Arch Sex Behav 2004;33:343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Azim T, Bontell I, Strathdee SA. Women, drugs and HIV. Int J Drug Policy 2015;26:S16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Larney S, Mathers BM, Poteat T, Kamarulzaman A, Degenhardt L. Global epidemiology of HIV among women and girls who use or inject drugs: current knowledge and limitations of existing data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69:S100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ma PHX, Chan ZCY, Loke AY. The socio-ecological model approach to understanding barriers and facilitators to the accessing of health services by sex workers: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2412–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. Hoboken, NJ: [Internet. Wiley, 2008. https://books.google.com/books?id=1xuGErZCfbsC. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Robertson AM, Garfein RS, Wagner KD et al. Evaluating the impact of Mexico’s drug policy reforms on people who inject drugs in Tijuana, B.C., Mexico, and San Diego, CA, United States: a binational mixed methods research agenda. Harm Reduct J 2014;11:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J et al. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: a quasi-randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:1657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Garfein RS, Golub ET, Greenberg AE et al. A peer-education intervention to reduce injection risk behaviors for HIV and hepatitis C virus infection in young injection drug users. AIDS 2007;21:1923–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].West BS, Abramovitz D, Staines H, Vera A, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Predictors of injection cessation and relapse among female sex workers who inject drugs in two Mexican-US border cities. J Urban Health 2016;93:141–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rafful C, Jain S, Sun X et al. Identification of a Syndemic of blood-borne disease transmission and injection drug use initiation at the US-Mexico border. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;79:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Garfein RS, Swartzendruber A, Ouellet LJ et al. Methods to recruit and retain a cohort of young-adult injection drug users for the third collaborative injection drug users study/drug users intervention trial (CIDUS III/DUIT). Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;91:S4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Westreich D, Greenland S. The table 2 fallacy: presenting and interpreting confounder and modifier coefficients. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:292–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].VanderWeele TJ, Staudt N. Causal diagrams for empirical legal research: a methodology for identifying causation, avoiding bias and interpreting results. Law Probab Risk 2011;10:329–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pitpitan EV, Patterson TL, Abramovitz D et al. Policing behaviors, safe injection self-efficacy, and intervening on injection risks: moderated mediation results from a randomized trial. Health Psychol 2016;35: 87–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Celentano DD, Cohn S, Davis RO, Vlahov D. Self-efficacy estimates for drug use practices predict risk reduction among injection drug users. J Urban Health 2002;79:245–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Latka MH, Hagan H, Kapadia F et al. A randomized intervention trial to reduce the lending of used injection equipment among injection drug users infected with hepatitis C. Am J Public Health 2008;98:853–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ et al. Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2013;43:235–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J et al. Needle syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;9:CD012021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Patel MR, Foote C, Duwve J et al. Reduction of injection-related risk behaviors after emergency implementation of a syringe services program during an HIV outbreak. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77: 373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cepeda JA, Burgos JL, Kahn JG et al. Evaluating the impact of global fund withdrawal on needle and syringe provision, cost and use among people who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico: a costing analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Smith DM, Werb D, Abramovitz D et al. Predictors of needle exchange program utilization during its implementation and expansion in Tijuana. Mexico Am J Addict 2016;25:118–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pines HA, Goodman-Meza D, Pitpitan EV, Torres K, Semple SJ, Patterson TL. HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Tijuana, Mexico: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Pitpitan EV, Goodman-Meza D, Burgos JL et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV among men who have sex with men in Tijuana. Mexico J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:19304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Archibald CP et al. Social determinants predict needle-sharing behaviour among injection drug users in Vancouver. Canada Addiction 1997;92:1339–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Edlin BR. Sexual transmission of HIV-1 among injection drug users in San Francisco, USA: risk-factor analysis. Lancet 2001;357:1397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tavitian-Exley I, Boily MC, Heimer R, Uusküla A, Levina O, Maheu-Giroux M. Polydrug use and heterogeneity in HIV risk among people who inject drugs in Estonia and Russia: a latent class analysis. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1329–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Meacham MC, Roesch SC, Strathdee SA, Lindsay S, Gonzalez-Zuniga P, Gaines TL. Latent classes of polydrug and polyroute use and associations with human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviours and overdose among people who inject drugs in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37:128–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Goodman-Meza D, Medina-Mora ME, Magis-Rodríguez C, Landovitz RJ, Shoptaw S, Werb D. Where is the opioid use epidemic in Mexico? A cautionary tale for policymakers south of the US–Mexico border. Am J Public Health 2019;109:73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Karila L, Weinstein A, Aubin H, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, Batki SL. Pharmacological approaches to methamphetamine dependence: a focused review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;69:578–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Carrico AW, Jain J, Discepola MV et al. A community-engaged randomized controlled trial of an integrative intervention with HIV-positive, methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. BMC Public Health 2016;16:673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Iversen J, Page K, Madden A, Maher L. HIV, HCV, and health-related harms among women who inject drugs: implications for prevention and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69:S176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Stone J, Fraser H, Lim AG et al. Incarceration history and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cepeda JA, Niccolai LM, Lyubimova A, Kershaw T, Levina O, Heimer R. High-risk behaviors after release from incarceration among people who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;147:196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bluthenthal R, Lorvick J, Kral A, Erringer E, Kahn J. Collateral damage in the war on drugs: HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy 1999;10:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV infection among female sex workers who inject drugs in the Mexico-US border region. PLoS One 2011;6:e19048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Beletsky L, Wagner KD, Arredondo J et al. Implementing Mexico’s “Narcomenudeo” drug law reform: a mixed methods assessment of early experiences among people who inject drugs. J Mix Methods Res 2015; 10:384–401. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Lozada RM et al. Syringe possession arrests are associated with receptive syringe sharing in two Mexico-US border cities. Addiction 2008;103:101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Pollini RA et al. Individual, social, and environmental influences associated with HIV infection among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47: 369–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Borquez A, Beletsky L, Nosyk B et al. The effect of public health-oriented drug law reform on HIV incidence in people who inject drugs in Tijuana, Mexico: an epidemic modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2018;3:e429–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rao A, Tobin K, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Social desirability bias and prevalence of sexual HIV risk behaviors among people who use drugs in Baltimore, Maryland: implications for identifying individuals prone to underreporting sexual risk behaviors. AIDS Behav 2017;21:2207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Smith TW. Discrepancies between men and women in reporting number of sexual partners: a summary from four countries. Soc Biol 1992;39:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lee N, Boeri M. Managing stigma: women drug users and recovery services. Fusio 2017;1:65–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]