Abstract

Purpose:

While many youth consider suicide, only a subset act on suicidal thoughts and attempt suicide. The objective of this study was to identify patterns of risk factors that differentiate adolescents who experienced suicidal thoughts from those who attempted suicide.

Methods:

This study analyzed data from the 2013, 2015, and 2017 National Youth Risk Behavior Surveys. Classification tree analysis was used to identify combinations of health risk behaviors and demographic factors that improved the identification of past-year suicide attempts among adolescents with past-year suicide ideation or planning (overall n = 7,493).

Results:

Forty percent of the past-year ideators attempted suicide in the same time period. The best-performing tree included three variables and defined four subgroups. Youth characterized by heroin use and past-year physical fights were at a strikingly high risk of being attempters (78%). Youth who had experienced rape were also likely to be attempters (58%), while those who had endorsed none of these three variables were relatively less likely to be attempters (29%). Overall, the tree’s classification accuracy was modest (Area under the Curve = 0.65).

Conclusions:

This study advances previous research by identifying notable constellations of risk behaviors that accounted for adolescents’ transition from suicidal ideation to behavior. However, even with many health risk behavior variables, a large sample, and a multidimensional analytic approach, the overall classification of suicide attempters among ideators was limited. Implications for future research are discussed.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among youth in the United States [1], and its prevalence among young people has steadily increased in recent years [2]. The transition to adolescence is a sensitive developmental period during which suicidal ideation and suicide attempts typically begin. Suicidal ideation increases rapidly between ages 12 and 17, while the rates of suicide attempts rise between the ages of 12 and 15 [3]. According to recent estimates, as many as 17.2% of high school students in the United States seriously considered suicide and 7.4% attempted suicide in the previous year [4]. Suicidal ideation and attempts are associated with significant distress and may lead to long-standing psychosocial impairment [5,6]. Nationally, reducing suicidal behaviors (suicide deaths and suicide attempts) has been highlighted as a public heath priority [7].

Research over the last several decades has identified a wide range of risk factors associated with suicidal ideation and behavior, spanning demographic (e.g., female sex, older age), clinical (e.g., previous suicide attempt, depression, hopelessness, nonsuicidal self-injury, substance use disorders), biological (e.g., neurobiological, molecular, genetic factors), and social domains (e.g., disconnection, peer victimization, maltreatment) (see reviews: Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006; Cha et al., 2018; Spirito & Esposito-Smythers, 2006). While previous research has contributed to an improved understanding of indicators and processes that contribute to suicide risk more generally, much less is known about what characterizes individuals who act on their suicidal thoughts, as opposed to those who think about suicide but do not make suicide attempts. This is an important knowledge gap, because most adolescents who experience suicidal ideation do not go on to attempt suicide; in fact, approximately 34% of adolescents who report suicidal ideation will make a suicide attempt [3]. In line with this, previous research has shown that suicidal ideation alone is not a reliable predictor of suicide attempts for all adolescents [11,12]. An improved understanding of what factors are associated with suicidal behavior in contrast to ideation among adolescents may provide opportunities to better identify those adolescents at greatest risk of acting on suicidal thoughts and points at which to disrupt this trajectory of risk.

Increasingly, empirical and theoretical work has used an ideation to action framework [13], which separately describes the variables and processes related to suicidal ideation from those related to suicide attempts. For example, recent work with a large sample of young adults [14] found that fearlessness about death and pain, death related imagery when distressed, and impulsivity were associated with reporting a history of a suicide attempt as opposed to suicide ideation without attempting. On the other hand, a sense of feeling defeated or like one was a burden was associated with a history of suicide ideation compared to no suicidal experiences, but did not differentiate between attempters and ideators [14].

Among adolescents specifically, existing research across population-based and clinical samples has provided important insights about differences between suicidal ideators and attempters, although the conclusions from this literature are somewhat varied. For example, demographic characteristics and psychiatric disorders do not appear to be consistently associated with the transition from ideation to attempts. There is, however, more uniform evidence pointing to behavioral disorders (oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorders) [3,15] as well as substance use disorders [3,16,17] accounting for some of these group differences. Along similar lines, externalizing problems [16] as well as heavy drinking and illicit drug use have been identified as significant factors differentiating ideators from attempters [15,17–20]. Violence and risk taking—e.g., getting into physical fights, engaging in risky sexual behavior and teen pregnancy, running away from home—constitute another category of experiences that differentiate ideators from attempters in population-based and clinical samples [16,18,21–23]. Exposure to maltreatment, such as experiencing physical or sexual abuse, being bullied, or experiencing dating violence, have also been found to contribute to the transition from ideation to attempts [18,23]. Finally, nonsuicidal self-injury has emerged in the adolescent literature as one of the more consistent markers differentiating ideators from attempters [17,19,22–24]. Related to this, some [15,16] have shown that being exposed to self-harm in others is similarly a risk factor for suicide attempts relative to suicidal ideation.

In summary, the literature comparing adolescents with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts is, with some exceptions, somewhat mixed. The inconsistency may be due to the fact that some of these studies, particularly in clinical settings, have relied on small samples. The majority of previous studies have also been limited by solely considering univariate relationships that may have obscured important group differences between ideators and attempters. Some studies have used traditional multivariable statistical models to examine which risk predictors had independent relationships with the probability of making an attempt when adjusting for others; however, none have used statistical approaches that have allowed for the examination of different pathways to suicide risk, possibly due to the small sample sizes. Indeed, relationships between specific risk factors and transition to attempt status may not be apparent for all adolescents, as revealed by examinations of specific moderators. For example, in previous studies, the associations between risk factors and attempt versus ideator status varied as a function of sex [16,23], clinical characteristics [20], and severity of suicidality (planning) [3]. This is consistent with findings from recent meta-analytic work demonstrating that many of the previously-identified risk factors—when considered individually—have shown strikingly poor prediction of suicidal behavior [25,26]. Thus, understanding differences between adolescent suicide ideators and attempters not only calls for replication in larger samples but also requires that studies consider different ways of combining risk factors. Approaches that consider many risk variables and their interactions at one time may reveal novel information about the multiple pathways that may result in suicide attempts among ideators and clues as to the processes that account for that transition. To our knowledge, this work has not yet been done among adolescents.

The objective of this study was, consistent with the ideation-to-action framework, to identify patterns of risk factors that differentiate adolescents who experience suicidal thoughts from those who attempted suicide. We advance previous work by utilizing a large sample of adolescents drawn from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) database, focusing on only those with past-year suicidal thoughts or past year suicidal behaviors, including a broad array of health risk behaviors in a single model, and employing classification tree analysis. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to model more complex and multi-dimensional risk processes, i.e., moving beyond univariate relationships or regression models, to identify different patterns of risk variables that are associated with a higher risk of engagement in suicidal behavior rather than suicidal thinking. This approach allows for the observation of moderating effects that might otherwise be missed when using traditional model-based approaches. Using an exploratory approach, this study sought to identify constellations of health risk behaviors that could become the target of prevention and intervention efforts in youth who are at heightened risk for suicidal behavior.

Methods

Data Source

Data included in these analyses came from the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The YRBS is a cross-sectional, school-based survey administered biennially in public and private schools in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Survey administration occurs during the school day and participation, via computer-scannable booklets, is voluntary and anonymous. When students complete the questionnaire, they seal the booklet in an envelope before depositing it in a box. The school then sends completed booklets to the CDC for processing. Students respond to questions about demographics and health risk behaviors. The current analyses included combined data from the 2013, 2015, and 2017 administrations. These administrations include unique students in each year. Because our research question focused on the relationships between health risk variables and suicide attempts among those with suicidal ideation, rather than describing the characteristics of the populations represented by the samples, survey weights were not used. Participants with missing data on the suicide items were excluded. Further details related to the YRBS sampling and assessment strategies have been reported elsewhere [4,27]. The national YRBS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the CDC.

Participants

Participants consisted of 7,433 students reporting past year suicide ideation and/or attempt. Participants were predominantly female (63.9%), white (44.3%), and between the ages of 15 and 17 (74.4%). Participants were well distributed across grades: 9th (26.6%), 10th (24.6%), 11th (25.0%), 12th (22.8%) and ungraded or other (0.4%).

Measures

Outcome variable.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the last 12 months were queried with three items: (1) “During the past 12 months did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” (yes/no), (2) “During the past 12 months did you make a plan as to how you would attempt suicide?” (yes/no), and (3) “During the past 12 months how many times did you actually attempt suicide?” (0, 1 time, 2 or 3 times, 4 or 5 times, or 6 or more times). A binary outcome variable was created such that all respondents who reported one or more suicide attempts were coded as attempters (n=3,055) and all respondents who report suicidal ideation or a suicide plan and denied a suicide attempt were coded as ideators (n=4,438). Respondents who reported no suicide ideation, plans or attempts in the past 12 months (n=27,361) and those who skipped a question precluding their categorization into one of the above groups (n=9,168) were excluded from the analyses.

Predictors.

Sixty-two predictors of suicide attempts were drawn from the YRBS demographic and health risk behavior items (see Table 1 for detailed descriptions). They included measures of demographics, safety, interpersonal violence, substance use, sexual health, physical and mental health, and use of electronics. Items varied in terms of their response sets, but included dichotomous, Likert-type, ordinal and frequency items. Survey year was also included as a predictor to capture potential changes over time in the importance of different predictors.

Table 1.

YRBS demographic and health risk behavior items

| Construct | Question | Response options | Prev. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | How old are you? | 1 = 12 years old or younger 2 = 13 years old 3 = 14 years old 4 = 15 years old 5 = 16 years old 6 = 17 years old 7 = 18 years old or older |

5.04 (1.25) | |

| Race/eth. | What is your race? Select one or more responses Are you Hispanic or Latino? |

1= American Indian or Alaska Native 2= Asian 3= Black or African American 4= Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander 5= White 6= Hispanic/Latino 7= Multiple – Hispanic 8= Multiple - Non-Hispanic |

1.2% (86) 4.7% (330) 14.5% (1019) 0.8% (56) 44.3% (3107) 12.8% (901) 18.8% (1318) 7.2% (504) |

|

| Sex | What is your sex? | 1= Female 2= Male |

63.9% (4746) 36.1% (2687) |

|

| Safety | ||||

| Seatbelt | How often do you wear a seat belt when riding in a car driven by someone else? | 1= Never 2= Rarely 3= Sometimes 4= Most of the time 5= Always |

3.37 (1.51) | |

| Riding with a drinking driver | During the past 30 days, how many times did you ride in a car or other vehicle driven by someone who had been drinking alcohol? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or more times |

1.59 (1.12) | |

| Drinking and drivinga | During the past 30 days, how many times did you drive a car or other vehicle when you had been drinking alcohol? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or more times |

1.30 (0.88) | |

| Texting and drivinga | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you text or e-mail while driving a car or other vehicle? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 5 days 4= 6 to 9 days 5= 10 to 19 days 6= 20 to 29 days 7= All 30 days |

2.51 (2.58) | |

| Drive | Recoded from the Drinking and driving item and indicates whether the respondent drove a car or other vehicle in the last 30 days | 1= Yes 2= No |

56.5% (3815) | |

| Weapon carrying | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you carry a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 day 3= 2 or 3 days 4= 4 or 5 days 5= 6 or more days |

1.67 (1.35) | |

| Weapon carrying at school | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you carry a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 day 3= 2 or 3 days 4= 4 or 5 days 5= 6 or more days |

1.25 (0.88) | |

| Gun carryingb | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school because you felt you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 day 3= 2 or 3 days 4= 4 or 5 days 5= 6 or more days |

1.19 (0.75) | |

| Interpersonal Violence | ||||

| Cyberbulliedc | Have you ever been electronically bullied? (Count being bullied through e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, websites, or texting.) | 1= Yes 2= No |

31.2% (2325) | |

| Bullied at school | Have you ever been bullied on school property? | 1= Yes 2= No |

38.4% (2858) | |

| School absence due to safety concerns at /near school | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you not go to school because you felt you would be unsafe at school or on your way to or from school? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 day 3= 2 or 3 days 4= 4 or 5 days 5= 6 or more days |

1.29 (0.82) | |

| Threatened or injured with a weapon at school | During the past 12 months, how many times has someone threatened or injured you with a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club on school property? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or 7 times 6= 8 or 9 times 7= 10 or 11 times 8= 12 or more times |

1.40 (1.31) | |

| In a physical fight | During the past 12 months, how many times were you in a physical fight? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or 7 times 6= 8 or 9 times 7= 10 or 11 times 8= 12 or more times |

1.88 (1.62) | |

| In a physical fight at school | During the past 12 months, how many times were you in a physical fight on school property? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or 7 times 6= 8 or 9 times 7= 10 or 11 times 8= 12 or more times |

1.29 (1.01) | |

| Dated | Recoded from the physical dating violence item and indicates whether the respondent dated or went out with anyone in the past 12 months | 1= Yes 2= No |

76.0% (5312) | |

| Physical dating violence | During the past 12 months, how many times did someone you were dating or going out with physically hurt you on purpose? (Count such things as being hit, slammed into something, or injured with an object or weapon.)d | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or more times |

1.49 (1.06) | |

| Sexual dating violence | During the past 12 months, how many times did someone you were dating or going out with force you to do sexual things that you did not want to do? (Count such things as kissing, touching, or being physically forced to have sexual intercourse.)d | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or 3 times 4= 4 or 5 times 5= 6 or more times |

1.48 (1.04) | |

| Lifetime forced sex | Have you ever been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to? | 1= Yes 0= No |

19.3% (1403) | |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Lifetime cigarette use | Have you ever tried cigarette smoking, even one or two puffs? | 1= Yes 2= No |

48.1% (3467) | |

| Age of first cigarette use | How old were you when you smoked a whole cigarette for the first time? | A. I have never smoked a whole cigarette B. 8 years old or younger C. 9 or 10 years old D. 11 or 12 years old E. 13 or 14 years old F. 15 or 16 years old G. 17 years old or older |

59.6% (4232) 4.3% (305) 3.6% (255) 6.5 % (464) 12.8% (908) 10.3% (729) 3.0% (215) |

|

| Current cigarette use frequency | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 5 days 4= 6 to 9 days 5= 10 to 19 days 6= 20 to 29 days 7= All 30 days |

1.68 (1.61) | |

| Current cigarette use quantity | During the past 30 days, on the days you smoked, how many cigarettes did you smoke per day? | 1= I did not smoke cigarettes during the past 30 days 2= Less than 1 cigarette per day 3= 1 cigarette per day 4= 2 to 5 cigarettes per day 5= 6 to 10 cigarettes per day 6= 11 to 20 cigarettes per day 7= More than 20 cigarettes per day |

1.55 (1.26) | |

| Current smokeless tobacco use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip, such as Redman, Levi Garrett, Beechnut, Skoal, Skoal Bandits, or Copenhagen?e | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 5 days 4= 6 to 9 days 5= 10 to 19 days 6= 20 to 29 days 7= All 30 days |

1.30 (1.14) | |

| Current cigar use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 5 days 4= 6 to 9 days 5= 10 to 19 days 6= 20 to 29 days 7= All 30 days |

1.43 (1.23) | |

| Lifetime alcohol use | During your life, on how many days have you had at least one drink of alcohol? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 9 days 4= 10 to 19 days 5= 20 to 39 days 6= 40 to 99 days 7= 100 or more days |

3.37 (1.94) | |

| Current alcohol use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol? | 1= 0 days 2= 1 or 2 days 3= 3 to 5 days 4= 6 to 9 days 5= 10 to 19 days 6= 20 to 29 days 7= All 30 days |

1.94 (1.36) | |

| Current binge drinking | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours? | 1= 0 days B. 1 day C. 2 days D. 3 to 5 days E. 6 to 9 days F. 10 to 19 days G. 20 or more days |

1.63 (1.29) | |

| Lifetime marijuana use | During your life, how many times have you used marijuana? | 1= 0 times B. 1 or 2 times C. 3 to 9 times D. 10 to 19 times E. 20 to 39 times F. 40 to 99 times G. 100 or more times |

2.98 (2.31) | |

| Current marijuana use | During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.92 (1.55) | |

| Lifetime cocaine use | During your life, how many times have you used any form of cocaine, including powder, crack, or freebase? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.26 (0.92) | |

| Lifetime glue use | During your life, how many times have you sniffed glue, breathed the contents of aerosol spray cans, or inhaled any paints or sprays to get high? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.39 (1.03) | |

| Lifetime heroin use | During your life, how many times have you used heroin (also called smack, junk, or China White)? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.16 (0.76) | |

| Lifetime methamphetamine use | During your life, how many times have you used methamphetamines (also called speed, crystal, crank, or ice)? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.20 (0.84) | |

| Lifetime ecstasy use | During your life, how many times have you used ecstasy (also called MDMA)? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.26 (0.89) | |

| Lifetime steroid use | During your life, how many times have you taken steroid pills or shots without a doctor’s prescription? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.20 (0.84) | |

| Lifetime prescription drug misuse | During your life, how many times have you taken a prescription drug (such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, codeine, Adderall, Ritalin, or Xanax) without a doctor’s prescription?g | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.74 (1.36) | |

| Lifetime hallucinogenic drug use | During your life, how many times have you used hallucinogenic drugs, such as LSD, acid, PCP, angel dust, mescaline, or mushrooms? | A. 0 times B. 1 or 2 times C. 3 to 9 times D. 10 to 19 times E. 20 to 39 times F. 40 or more times |

1.30 (0.92) | |

| Ever injected illegal drugs | During your life, how many times have you used a needle to inject any illegal drug into your body? | 1= 0 times 2= 1 time 3= 2 or more times |

1.08 (0.36) | |

| Age of first alcohol use | How old were you when you had your first drink of alcohol, other than a few sips? | 1= I have never had a drink of alcohol other than a few sips 2= 8 years old or younger 3= 9 or 10 years old 4= 11 or 12 years old 5= 13 or 14 years old 6= 15 or 16 years old 7= 17 years old or older |

24.6% (1784) 9.4% (685) 6.2% (448) 11.4% (827) 24.5% (1776) 20.3% (1475) 3.7% (265) |

|

| Source of alcohol used | During the past 30 days, how did you usually get the alcohol you drank? | 1= I did not drink alcohol during the past 30 days 2= I bought it in a store such as a liquor store, convenience store, supermarket, discount store, or gas station 3= I bought it at a restaurant, bar, or club 4= I bought it at a public event such as a concert or sporting event 5= I gave someone else money to buy it for me 6= Someone gave it to me 7= I took it from a store or family member 8= I got it some other way |

52.8% (3456) 2.7% (176) 0.9% (57) 0.5% (33) 8.1% (533) 19.6% (1284) 7.0% (459) 8.3% (544) |

|

| Age of first marijuana use | How old were you when you tried marijuana for the first time? | A. I have never tried marijuana B. 8 years old or younger C. 9 or 10 years old D. 11 or 12 years old E. 13 or 14 years old F. 15 or 16 years old G. 17 years old or older |

45.8% (3348) 3.0% (223) 2.5% (185) 8.1% (593) 19.7% (1438) 17.2% (1258) 3.7% (270) |

|

| Offered illegal drugs at school (past 12 months) | During the past 12 months, has anyone offered, sold, or given you an illegal drug on school property? | 1= Yes 2= No |

36.2% (2619) | |

| Sexual Health | ||||

| Sexual intercourse (lifetime) | Have you ever had sexual intercourse? | 1= Yes 2= No |

54.8% (3786) | |

| Age of first intercourse | How old were you when you had sexual intercourse for the first time? | 1= I have never had sexual intercourse 2= 11 years old or younger 3= 12 years old 4= 13 years old 5= 14 years old 6= 15 years old 7= 16 years old 8= 17 years old or older |

47.2% (3124) 5.3% (349) 3.0% (200) 6.8% (449) 13.3% (879) 14.2% (938) 9.7% (643) 0.5% (30) |

|

| Alcohol/drug before sex (most recent) | Did you drink alcohol or use drugs before you had sexual intercourse the last time? Factor |

A. I have never had sexual intercourse B. Yes C. No |

45.2% (3065) 13.5% (914) 41.3% (2804) |

|

| Condom use (most recent) | The last time you had sexual intercourse, did you or your partner use a condom? | A. I have never had sexual intercourse B. Yes C. No |

45.7% (3117) 27.9% (1906) 26.4% (1805) |

|

| Birth control method (most recent) | The last time you had sexual intercourse, what one method did you or your partner use to prevent pregnancy? (Select only one response.) | 1= I have never had sexual intercourse 2= No method was used to prevent pregnancy 3= Birth control pills 4= Condoms 5= An IUD (such as Mirena or ParaGard) or implant (such as Implanon or Nexplanon) 6= A Shot (such as Depo-Provera), patch (such as Ortho Evra), or birth control ring (such as NuvaRing) 7= Withdrawal or some other method 8= Not sure |

47.3% (3116) 10.9% (715) 8.2% (540) 22.9% (1505) 1.6% (104) 2.2% (146) 6.9% (456) 2.3% (154) |

|

| Number of sexual partners (lifetime) | During your life, with how many people have you had sexual intercourse? | 1= I have never had sexual intercourse 2= 1 person 3= 2 people 4= 3 people 5= 4 people 6= 5 people 7= 6 or more people |

2.53 (1.97) | |

| Number of sexual partners (past 90 days) | During the past 3 months, with how many people did you have sexual intercourse? | 1= I have never had sexual intercourse 2= I have had sexual intercourse, but not during the past 3 months 3= 1 person 3= 2 people 4= 3 people 5= 4 people 6= 5 people 7= 6 or more people |

45.3% (3105) 14.5% (995) 29.4% (2016) 5.3% (362) 2.1% (144) 1.0% (71) 0.4% (24) 2.0% (138) |

|

| Physical & Mental Health | ||||

| Sad and hopeless | During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities? | 1= Yes 2= No |

75.5% (5624) | |

| Asthma | Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you have asthma? | 1= Yes 2= No 3= Not sure |

28.1% (1952) 66.2% (4607) 5.7% (398) |

|

| Sleep | On an average school night, how many hours of sleep do you get? | 1= 4 or less hours 2= 5 hours 3= 6 hours 4= 7 hours 5= 8 hours 6= 9 hours 7= 10 or more hours |

3.16 (1.48) | |

| Physical activity (past week) | During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? (Add up all the time you spent in any kind of physical activity that increased your heart rate and made you breathe hard some of the time.) | 1= 0 days 2= 1 day 3= 2 days 4= 3 days 5= 4 days 6= 5 days 7= 6 days 8= 7 days |

4.46 (2.51) | |

| Perception of weight | How do you describe your weight? | 1=. Very underweight 2= Slightly underweight 3= About the right weight 4= Slightly overweight 5= Very overweight |

3.31 (0.95) | |

| Trying to change weight | Which of the following are you trying to do about your weight? | 1= Lose weight 2= Gain weight 3= Stay the same weight 4= I am not trying to do anything about my weight |

58.3% (4222) 15.5% (1120) 11.6% (838) 14.7% (1062) |

|

| Indoor tanning (past year)h | During the past 12 months, how many times did you use an indoor tanning device such as a sunlamp, sunbed, or tanning booth? (Do not include getting a spray-on tan.) | 1= 0 times 2= 1 or 2 times 3= 3 to 9 times 4= 10 to 19 times 5= 20 to 39 times 6= 40 or more times |

1.25 (0.91) | |

| Electronic Use | ||||

| Hours of TV | On an average school day, how many hours do you watch TV? | 1= I do not watch TV on an average school day 2= Less than 1 hour per day 3= 1 hour per day 4= 2 hours per day 5= 3 hours per day 6= 4 hours per day 7= 5 or more hours per day |

3.41 (1.96) | |

| Hours of computers/video gamesi | On an average school day, how many hours do you play video or computer games or use a computer for something that is not school work? (Count time spent on things such as Xbox, PlayStation, an iPod, an iPad or other tablet, a smartphone, YouTube, Facebook or other social networking tools, and the Internet.) | 1= I do not play video or computer games or use a computer for something that is not school work 2= Less than 1 hour per day 3= 1 hour per day 4= 2 hours per day 5= 3 hours per day 6= 4 hours per day 7= 5 or more hours per day |

4.46 (2.21) | |

| Other | ||||

| Study Year | Study Year | 1= 2013 2= 2015 3= 2017 |

32.5% (2437) 37.4% (2800) 30.1% (2256) |

Respondents who indicated they hadn’t driven a car in the past 30 days were excluded.

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to During the past 12 months, on how many days did you carry a gun? (Do not count the days when you carried a gun only for hunting or for a sport, such as target shooting.)

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to Have you ever been electronically bullied? (Count being bullied through texting, Instagram, Facebook, or other social media.)

Respondents who indicated they hadn’t dated or gone out with anyone in the past 12 months were excluded

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, snus, or dissolvable tobacco products, such as Redman, Levi Garrett, Beechnut, Skoal, Skoal Bandits, Copenhagen, Camel Snus, Marlboro Snus, General Snus, Ariva, Stonewall, or Camel Orbs? (Do not count any electronic vapor products.)

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 4 or more drinks of alcohol in a row (if you are female) or 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row (if you are male)?

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to During your life, how many times have you taken prescription pain medicine without a doctor’s prescription or differently than how a doctor told you to use it? (Count drugs such as codeine, Vicodin, OxyContin, Hydrocodone, and Percocet.)

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to During the past 12 months, how many times did you use an indoor tanning device such as a sunlamp, sunbed, or tanning booth? (Do not count getting a spray-on tan.)

In the 2017 YRBS the wording of this item was changed to On an average school day, how many hours do you play video or computer games or use a computer for something that is not school work? (Count time spent on things such as Xbox, PlayStation, an iPad or other tablet, a smartphone, texting, YouTube, Instagram, Facebook, or other social media.)

Statistical Analysis

Given that our objective was to examine predictors of suicide attempts among individuals with suicidal ideation in this sample and not to make population inferences about descriptive or analytic parameters, we did not consider YRBS weights in the analyses. Our results therefore only apply to this specific combined sample of YRBS data. We began with descriptive analyses of the outcome variable and each of the predictor variables under consideration (see Table 1). Overall, 40.8% of this sample attempted suicide in the past year, and 59.2% only had suicidal ideation in the past year.

Our primary exploratory analysis then utilized recursive partitioning (implemented in the rpart and rparty packages in the R software) to construct classification trees enabling the assessment of important predictors of suicide attempts, including more complex interactions between the predictors that were relevant in predicting the probability of an attempt. Small amounts of item-missing data on the predictor variables were accounted for in the analysis using a surrogate variable approach [28]. Briefly, in the context of classification trees, surrogates are variables identified by the classification tree algorithm as having a reasonably strong association with the variable on which a specific split in the tree is based. When testing the tree’s performance and making predictions for the values of the dependent variable (e.g., in cross-validation), if a case in the test data set has a missing value on the variable being used at a specific split in the tree, a decision is instead based on the “best” surrogate that does the “next best” job of explaining deviance in the outcome at that point in the tree (or the second-best surrogate, etc. if values on previous surrogates are missing as well)[28].

We employed 10-fold cross-validation to estimate the true error rates associated with competing trees of different sizes (in terms of terminal nodes), and computed AUC, sensitivity and specificity of the final tree for evaluating overall predictive performance. The objective of a classification tree is to optimize explanation of the deviance in a given binary outcome by forming nodes defined by combinations of values on the input predictors. We note that this approach does not accommodate hypothesis testing, nor does it generate p-values enabling tests of pre-specified hypotheses about parameters of interest in a statistical model. We ultimately arrived at a final tree that produced the highest predictive accuracy based on cross-validation using the smallest number of terminal nodes. We note that in this type of analysis, all variables function as both predictors and potential moderators. For example, if a different set of risk predictors better identifies attempters for boys versus girls, then sex will appear in the tree as a meaningful predictor variable.

Results

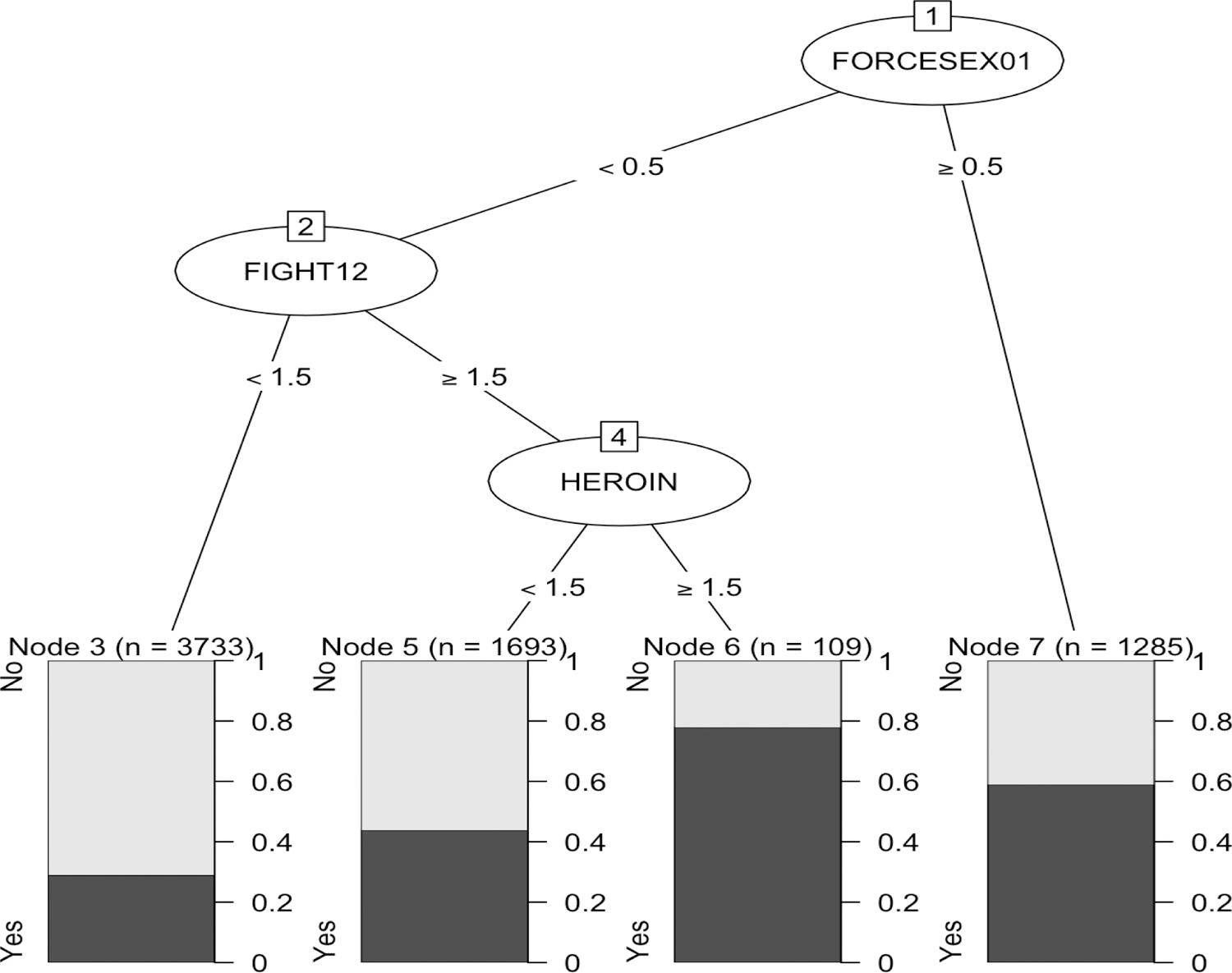

The final tree produced by the aforementioned pruning process is displayed in Fig. 1. All respondents reported suicide ideation and/or attempt. This tree is defined by three variables: a lifetime history of rape, having been in one or more physical fights in the past year, and ever having used heroin. The four subgroups of participants identified by the terminal nodes are as follows: (1) ideators who had ever been forced to have sex had a high probability of a suicide attempt (59%), (2) ideators who had never been forced to have sex and had not been in a physical fight in the past year had a low probability of a suicide attempt (29%), (3) ideators who had never been forced to have sex, had been in a physical fight in the past year, and had ever used heroin had a very high probability of attempt (78%), and (4) ideators who had never been forced to have sex, had been in a physical fight in the past year, and had never used heroin had a moderate probability of an attempt (44%).

Figure 1.

Results of Classification Tree Analysis predicting suicide attempts (Yes) compared to suicide ideation (No).

Note. FORCESEX01=Lifetime history of rape, 0=No, 1= Yes; FIGHT12=Past-year physical fight, 1=0 times, 2= 1 times, 3= 2 or 3 times, 4= 4 or 5 times, 5= 6 or 7 times, 6= 8 or 9 times, 7=10 or 11 times, 8= 12 or more times; HEROIN=Lifetime heroin use, 1= 0 times, 2= 1 or 2 times, 3= 3 to 9 times, 4= 10 to 19 times, 5= 20 to 39 times, 6= 40 or more times.

This tree had an AUC of .65 (95% CI = 0.633 – 0.660). The tree had a sensitivity of .87, a specificity of .32, a positive predictive value of .65 (and thus a false discovery rate of .35) and a negative predictive value of .62. The cross-validated error rate of the final tree was 35.6%, which represents an improvement of 5.2 percentage points over the root node error rate (40.8%), or the percentage of cases that would be incorrectly classified by simply predicting that every case in the data set belongs to the most common class (ideators).

Discussion

Previous research has identified important differences between adolescents who experience suicidal ideation and those who attempt suicide (e.g., Georgiades et al., 2019; Mars et al., 2019b; Nock et al., 2013; Stack, 2014). However, existing studies typically focus on individual risk factors, providing limited information about more complex pathways that may differentiate these two groups. This limitation is notable given that meta-analytic studies have shown individual risk factors to be poor predictors of suicidal behavior [25,26]. In a large sample of high school students, the current study sought to advance previous literature by applying classification tree analysis to identify constellations of risk variables that maximally differentiate adolescents with past-year suicidal thoughts from those with past-year suicide attempts. The results of this study highlight the challenge of obtaining high clinical utility in classifying suicidal ideators and attempters via health risk behaviors. At the same time, in line with the ideation-to-action framework, we found notable patterns in specific risk variables that reliably identified adolescents who attempted suicide in contrast to those considering suicide.

Understanding or identifying risk for suicide attempts among those who think about suicide is a decidedly difficult task – something that held true in this study as well. Even a statistical approach that combined information and interactions from 62 health risk behaviors among over 7,000 youth improved the error rate in classifications of attempts among ideators only marginally (5.2 percentage points compared to a model without predictors). Further, mirroring a challenge consistently observed in the literature, the node with the highest proportion of ideators (the node described by an absence of rape and absence of past-year fights) also had the highest number of students who had attempted (over 1,000). Stated another way, among the large group of attempters in this node, there were no robust combinations of health risk behaviors that differentiated them from their peers who considered suicide. Thus, for the majority of adolescents, health risk behaviors, even in combination, were not sensitive to this important distinction. While it has been well established that any single individual health risk behavior will not identify the majority of suicide attempters [26,29], these results suggest that efforts to look at large numbers of variables in combination also do not provide complete answers.

Importantly, however, these conclusions are limited to the variables included in this model. For example, though these health variables had less to offer in terms of identifying attempters among ideators, there may be other variables or combinations of variables that provide more information. For example, nonsuicidal self injury, which is typically associated with attempts among ideators [17,19,22–24] was not available in the YRBS data set. Moreover, it is possible that some of the health risk behaviors were measured too distally in reference to the suicide attempt outcome. Given theoretical as well as research evidence describing the dynamic nature of suicide risk and associated risk factors [30–33] it may be that precision in differentiating these two groups was diminished as a result of the “past year” timeframe.

However, there were certain variables that were particularly associated with attempts rather than ideation – specifically a lifetime history of rape. Almost two thirds of adolescents with past-year suicidal ideation who endorsed a history of rape reported a past-year attempt compared to one third of the adolescents who did not report such a history. This is consistent with previous work that found a history of sexual abuse associated with attempts rather than ideation among adolescent girls [23]. Interestingly, no other variables added incrementally to the identification of attempts among this group of ideators. Examining this bivariate association using a simple logistic regression may have revealed a strong relationship between a history of rape and attempt status. A multivariable regression model may have revealed that a history of rape is associated with attempts above and beyond other health risk behaviors. However, the use of a classification tree approach provides additional insights. Specifically, that for this subgroup of teens with a history of rape, none of the many other demographic and health risk variables contributed to improving classification of attempters versus ideators.

In addition, there were certain combinations of variables that, while rare, were strongly associated with attempts rather than ideation. Specifically, among the remaining adolescents (i.e. those without history of rape), the combination of having been in a physical fight in the last year and having used heroin was associated with an almost 80% chance of reporting a past-year suicide attempt, rather than past-year suicide ideation. Though the number of students in this group is small, the proportion of attempters in this subpopulation was twice as high the proportion of attempters in the sample as a whole. This pattern of findings is consistent with previous studies showing that some of the more consistent predictors differentiating suicidal ideators from attempters included substance misuse as well as externalizing or behavioral problems [3,15,16,18,19]. However, analytic approaches that examine associations between variables and outcomes in a bivariate manner may not have been able to detect the more nuanced pattern of interactions found among these variables. Indeed, we would have not been able to identify this high-risk subgroup without an analytic approach that examined interactions across multiple health risk variables. Although relatively small in size, adolescents in this subgroup were at relatively greater risk for having attempted suicide than those identified by the single rape history variable. Thus, while sexual assault was a strong indicator for transition to suicide attempts among those with suicide ideation, another notable pathway among ideators was characterized by the absence of sexual assault history combined with externalizing (physical fighting) and illicit substance (heroin) use. Given the diverse pathways by which individuals arrive at suicidal thoughts and behavior, these results suggest that it is valuable to examine unique combinations of risk variables to a better understand of suicidal behavior.

It is important to note that the health risk variables that did emerge as most valuable in identifying suicide attempters were all consistent with contemporary theories of suicidal behaviors that emphasize the role of capability for suicide. Capability for suicide is the ability to approach the fear and pain associated with death combined with the practical knowledge as to how to do so [34,35]. Suicide capability, when it coincides with the presence of suicidal desire, is theorized to predict suicide attempts among ideators [36–38]. The variables that emerged as most strongly related to suicide attempts could all be viewed through the lens of capability. Specifically, a history of rape, engaging in physical fights, and using heroin are each associated with acquiring or demonstrating greater capability for suicidal action. Physical fighting and heroin use both involve actively causing physical pain and injury to oneself or someone else. Exposure to forced sexual intercourse is a particularly painful and provocative event. Further work is needed to identify whether capability is a common thread relating these three variables to suicidal behavior among ideators, however these findings are consistent with existing theoretical and empirical evidence.

These findings should be considered in light of the study’s strengths as well as limitations. The strengths of the study include a large sample of adolescents surveyed nationally, the application of a data-driven approach (classification tree model) involving a wide range of risk behaviors, and a focus on an important, yet relatively understudied, area of research among adolescents. A key limitation is the cross-sectional design of the study, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about the temporal relationship between predictors and the suicide attempt outcome. Although the associations found in this study are strictly correlational, the pattern of results may nevertheless be useful in identifying a subset of adolescents who may benefit from additional support. Additionally, the brief, self-report measurement, though essential to the scale and scope of the YRBS, may have contributed to errors in the classification of ideation and attempts [39]. Moreover, while the risk factors included in the analysis were consistent with the ideation-to-action framework and relevant theory—e.g., the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior [34,38] and the three-step theory (3ST) of suicide [36]—the variables included in the model were not exhaustive. In particular, we were unable to examine nonsuicidal self-injury, which is another important limitation given its consistent association with transition to attempts among adolescents [17,19,22–24]. Finally, even with the application of the 10-fold cross-validation procedure to guard against overfitting and improve the generalizability of results, future research is needed to validate these findings in independent samples. Future replications utilizing prospective designs will be particularly important. Observations of moderation effects are exploratory in nature and that our results require confirmatory replication in the future. However, in context of the ideation-to-action framework, this study has provided a starting point highlighting the value of considering multi-dimensional pathways that may differentiate suicidal ideators from suicide attempters.

Implications & Contributions Summary Statement:

While many health risk behaviors are associated with suicide ideation, much less is known about which patterns of behaviors are associated with suicide attempts among adolescents who think about suicide. This study found that certain combinations of risk factors predict attempts; however, despite a large sample and many variables, accurate classification was limited.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying cause of death 1999–2017.

- [2].Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016. [PubMed]

- [3].Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:300–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [5].Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, et al. Suicidal behaviour in adolescence and subsequent mental health outcomes in young adulthood. Psychol Med 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [6].Reinherz HZ, Tanner JL, Berger SR, et al. Adolescent suicidal ideation as predictive of psychopathology, suicidal behavior, and compromised functioning at age 30. Am J Psychiatry 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [7].National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Research Prioritization Task Force. A prioritized research agenda for suicide prevention: An action plan to save lives. Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2006;47:372–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cha CB, Franz PJ, M. Guzmán E, et al. Annual Research Review: Suicide among youth – epidemiology, (potential) etiology, and treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [10].Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and Completed Suicide in Adolescence. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2:237–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, et al. Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [12].King CA, Jiang Q, Czyz EK, et al. Suicidal ideation of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents has one-year predictive validity for suicide attempts in girls only. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [13].Klonsky ED, May AM. Differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators: A critical frontier for suicidology research. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 2014;44:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wetherall K, Cleare S, Eschle S, et al. Journal of Affective Disorders From ideation to action: Differentiating between those who think about suicide and those who attempt suicide in a national study of young adults. J Affect Disord 2018;241:475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, et al. What distinguishes adolescents with suicidal thoughts from those who have attempted suicide? A population-based birth cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [16].Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, et al. Pediatric emergency department suicidal patients: Two-site evaluation of suicide ideators, single attempters, and repeat attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [17].Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, et al. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [18].Stack S Differentiating suicide ideators from attempters: Violence - A research note. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [19].Georgiades K, Boylan K, Duncan L, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Youth Suicidal Ideation and Attempts: Evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [20].O’Brien KH, Becker SJ, Spirito A, et al. Differentiating adolescent suicide attempters from ideators: Examining the interaction between depression severity and alcohol use. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 2014;44:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mykletun A, Bjerkeset O, Dewey M, et al. Anxiety, depression, and cause-specific mortality: The HUNT study. Psychosom Med 2007;69:323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stewart JG, Esposito EC, Glenn CR, et al. Adolescent self-injurers: Comparing non-ideators, suicide ideators, and suicide attempters. J Psychiatr Res 2017;84:105–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [24].Zlotnick C, Donaldson D, Spirito A, et al. Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [25].Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 2016;46:225–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk Factors for Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Psychol Bull 2017;143:187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Heal 2002;31:336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ding Y, Simonoff JS. An investigation of missing data methods for classification trees applied to binary response data. J Mach Learn Res 2010;11:131–70. [Google Scholar]

- [29].May AM, Klonsky ED. What Distinguishes Suicide Attempters From Suicide Ideators? A Meta-Analysis of Potential Factors. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2016;23:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ben-Zeev D, Young MA, Depp CA. Real-time predictors of suicidal ideation: Mobile assessment of hospitalized depressed patients. Psychiatry Res 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [31].Kleiman EMEM, Turner BJBJ, Fedor S, et al. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J Abnorm Psychol 2017;126:726–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Czyz EK, King CA, Nahum-Shani I. Ecological assessment of daily suicidal thoughts and attempts among suicidal teens after psychiatric hospitalization: Lessons about feasibility and acceptability. Psychiatry Res 2018;267:566–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bryan C, Butner JE, May AM, et al. Nonlinear change processes and the emergence of suicidal behavior: A conceptual model based on the fluid vulnerability theory of suicide. New Ideas Psychol 2020;57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [35].May AM, Victor SE. From ideation to action: recent advances in understanding suicide capability. Curr Opin Psychol 2018;22:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Klonsky ED, May AM. The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int J Cogn Ther 2015;8:114–29. [Google Scholar]

- [37].O’Connor RC. The integratedmotivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis 2011;32:295–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, et al. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol Rev 2010;117:575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Millner AJ, Lee MD, Nock MK. Single-item measurement of suicidal behaviors: Validity and consequences of misclassification. PLoS One 2015;10:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]