SUMMARY

Light responses mediated by the photoreceptors play crucial roles in regulating different aspects of plant growth and development. An E3 ubiquitin ligase complex COP1/SPA, one of the central repressors of photomorphogenesis, is critical for maintaining the skotomorphogenesis. It targets several positive regulators of photomorphogenesis for degradation in darkness. Recently we revealed that bHLH factors, HECATEs, function as positive regulators of photomorphogenesis by directly interacting and antagonizing the activity of another group of repressors called PIFs. It was also shown that HECs are partially degraded in the dark through the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. However, the underlying mechanism of HECs degradation in the dark is still unclear. Here we show that HECs also interact with both COP1 and SPA proteins in darkness, and that HEC2 is directly targeted by COP1 for degradation via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. Moreover, COP1-mediated poly-ubiquitylation and degradation of HEC2 are enhanced by PIF1. Therefore, the ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of HECs are significantly reduced in both cop1 and pif mutants. Consistent with this, the hec mutants partially suppress photomorphogenic phenotypes of both cop1 and pifQ mutants. Collectively our work reveals that the COP1/SPA mediated ubiquitylation and degradation of HECs contributes to the coordination of skoto/photomorphogenic development in plants.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, HECATE, PIFs, E3 ligase COP1, photomorphogenesis

INTRODUCTION

As consequence of their sessile nature, plants are extremely sensitive to light conditions. A broad spectrum of light regimes, including those ranging from UV to visible wavelengths, have profound effects on many developmental programs during plant life cycle. These include seed germination, seedling etiolation, phototropic growth, flowering time, circadian clock, shade avoidance response and others (Casal, 2013, Legris et al., 2019). To perceive and respond to this broad light spectrum, plants have evolved a repertoire of photoreceptors to sense and transduce the signals. One of the best-characterized plant light receptors is phytochrome (phy), which perceives red/far-red light signals (Legris et al., 2019). Upon red light exposure, the inactive holophytochrome (Pr) of all family members changes its conformation to a biologically active Pfr form and migrates into nucleus (Legris et al., 2019). After nuclear migration, the active Pfr form interacts with a number of unrelated proteins, including a subset of bHLH (basic Helix-Loop-Helix) regulatory proteins called PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORs (PIFs) (Pham et al., 2018a). PIFs function as negative regulators of photomorphogenesis. Upon physical interaction, phys induce rapid phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of PIFs (Leivar and Quail, 2011, Pham et al., 2018a). Thus, phys promote photomorphogenesis in response to light while PIFs promote skotomorphogenic development in darkness.

Genetic and molecular studies also led to the identification of mutants with constitutive photomorphogenic (cop) response in the dark. This suggests that the genes affected in such mutants function as negative regulators of light signaling pathways (Lau and Deng, 2012, Hoecker, 2017). One of these genes called CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) encodes an E3 Ubiquitin ligase that is evolutionarily conserved from plants to human (Osterlund et al., 2000, Yi and Deng, 2005, Hoecker, 2017). Interestingly, COP1 forms complexes with the Serine/Threonine kinase SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA (SPA1–4) (Laubinger et al., 2004) in the dark. The morphological and gene expression phenotypes of cop1 and spaQ largely overlap (Ma et al., 2002, Paik et al., 2019, Pham et al., 2020) and the phenotypes of the weak alleles of cop1 is enhanced by spa mutants (Saijo et al., 2003, Seo et al., 2003, Ordoñez-Herrera et al., 2015), suggesting that these proteins function together in a genetic pathway. Thus, the COP1-SPA complexes target the positive regulators of photomorphogenesis (including LONG HYPOCOTYL 5, HY5; LONG HYPOCOTYL IN FAR-RED, HFR1; LONG AFTER FAR-RED LIGHT 1, LAF1 and others) for ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation (Saijo et al., 2003, Seo et al., 2003, Jang et al., 2005, Yang et al., 2005, Zhu et al., 2008, Hoecker, 2017, Pham et al., 2018b). COP1 also targets many other substrates including CONSTANS (CO) (Liu et al., 2008), EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3) and GIGANTEA (GI) (Yu et al., 2008), and F-boxes EIN3-BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN 1 (EBF1) and EBF2 for regulating flowering time, circadian clock and seedling emergence (Liu et al., 2008, Yu et al., 2008, Lau and Deng, 2012, Xu et al., 2015). PIF1 enhances the E3 ligase activity of COP1 to synergistically regulate the degradation of HY5 and HFR1 in the dark (Xu et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2015, Xu et al., 2017). Strikingly, during the dark to light transition, COP1/SPA also associates with CULLIN4 (CUL4) and acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to promote light-induced degradation of PIF1 (Zhu et al., 2015). In this process, SPA1 acts as a ser/thr kinase to induce rapid phosphorylation of PIF1 by forming a phyB-PIF1-SPA1 trimolecular complex (Paik et al., 2019). In summary, the COP1/SPA complex and PIFs play both synergistic and antagonistic roles in regulating plant growth and development.

In addition to these posttranslational regulations, PIF functions can also be modulated at DNA binding level. The HFR1 sequesters PIF1, PIF4, PIF5 and PIF7 to prevent the DNA binding activities of PIFs (Hornitschek et al., 2009, Shi et al., 2013, Hersch et al., 2014). We have recently identified an additional subset of bHLHs, the HECATE proteins (HEC1, 2 and 3), which play key roles in fertilization and also stem cell maintenance (Gremski et al., 2007, Schuster et al., 2014, Gaillochet et al., 2018), and as positive regulators of photomorphogenesis (Zhu et al., 2016, Pham et al., 2018a). At the molecular level HECs were found to modulate the expression of several direct and indirect PIFs target genes by heterodimerizing with PIFs and blocking their DNA binding and transcriptional activities. HECs were found to be stabilized in response to light, while partially degraded in the dark through the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. However, an E3 ligase responsible for HECs ubiquitylation and degradation in the dark was unknown. In this study, we demonstrate that COP1/SPA E3 ligase directly regulates the abundance of HECs through ubiquitylation and degradation in darkness to optimize the skotomorphogenic growth in Arabidopsis. Moreover, this study further strengthens the importance of fundamental coordination between COP1, SPA and PIFs in modulation of plant growth and development.

RESULTS

PIFs and COP1 promote the degradation of HEC2 posttranslationally in etiolated seedlings.

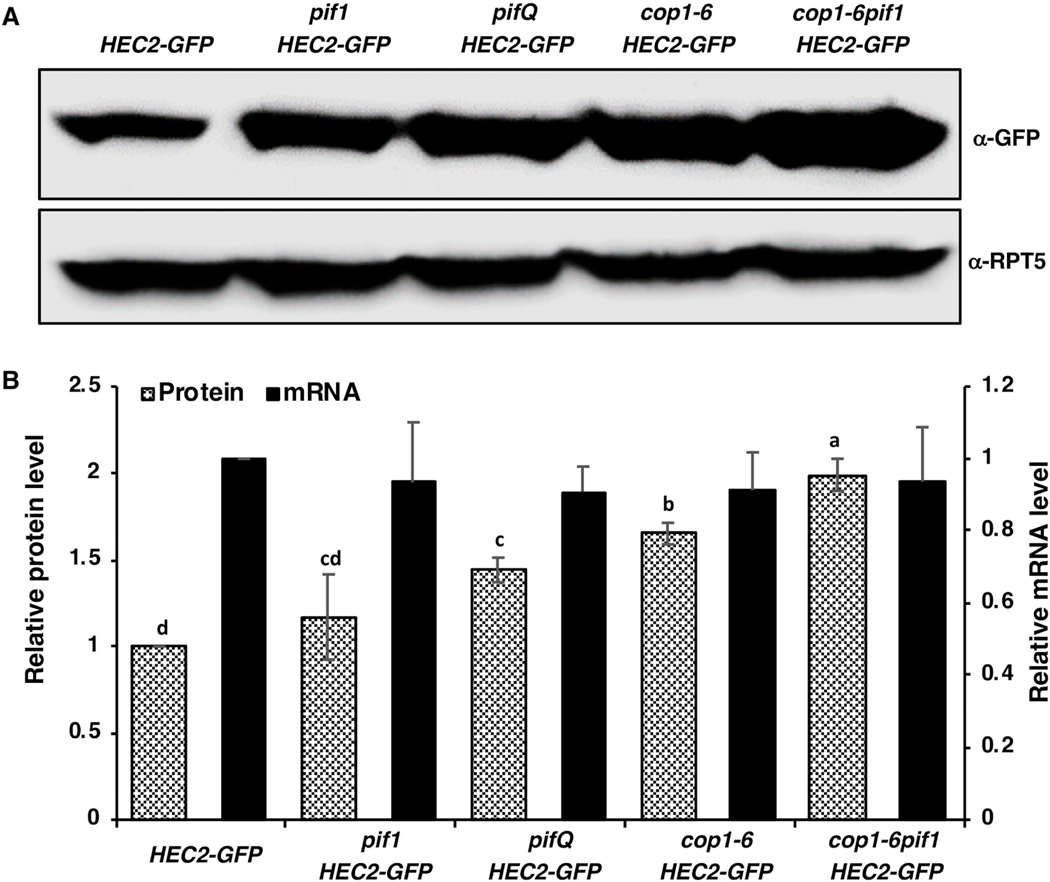

The facts that HECs are degraded in the dark and stabilized under light conditions (Zhu et al., 2016), led us to hypothesize whether HECs are indeed COP1 substrates, and their abundance is modulated synergistically by COP1/SPA complex and PIFs, similar to HY5 and HFR1 (Xu et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2017). Due to the unavailability of HECs antibodies as well as infertility of the 35S:HEC1-GFP and 35S:HEC3-GFP overexpression lines (Gremski et al., 2007), 35S:HEC2-GFP transgenic line (HEC2-GFP hereafter), ectopically expressing several folds higher HEC2 than wild type (Supplementary figure S1) was used throughout the study. We first examined both the transcript and protein levels of HEC2-GFP in HEC2-GFP, pif1/HEC2-GFP, pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP and cop1–6pif1/HEC2-GFP etiolated seedlings. The results show that the HEC2-GFP transcript remains largely unchanged in all tested genetic backgrounds, while the HEC2-GFP protein level was significantly higher in pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP and cop1–6pif1/HEC2-GFP compared to HEC2-GFP background (Figure 1A, B). Because cop1–6 is a weak allele, the addition of pif1 in the cop1–6 background could be reducing the residual action of COP1, resulting in an increased level of HEC2-GFP in the cop1–6pif1 double mutant (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1: PIFs and COP1 promote the degradation of HEC2 post-translationally in etiolated seedlings.

(A) Immunoblots showing HEC2-GFP protein accumulation in level in HEC2-GFP transgenic lines and in various mutants, respectively, harboring the HEC2-GFP transgene. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 4 days. Total protein was separated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, blotted onto PVDF membrane and probed with anti-GFP or anti-RPT5 antibodies. (B) Bar graph showing the HEC2-GFP protein (left Y-axis) and HEC2-GFP mRNA abundance (right Y-axis) in seedlings of the corresponding mutants. For protein quantitation, HEC2-GFP band intensities were quantified from three independent blots using ImageJ, and normalized against RPT5 levels. HEC2-GFP was set as 1 and the relative proteins levels were calculated. HEC2-GFP mRNA level was determined using qPCR assays with primers designed within the GFP coding region. Total RNA extractions were also performed using 4-day-old dark-grown seedlings. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n=3). The letters “a” to “c” indicate statistically significant differences between means of relative protein level among the genotypes based on one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (p<0.05).

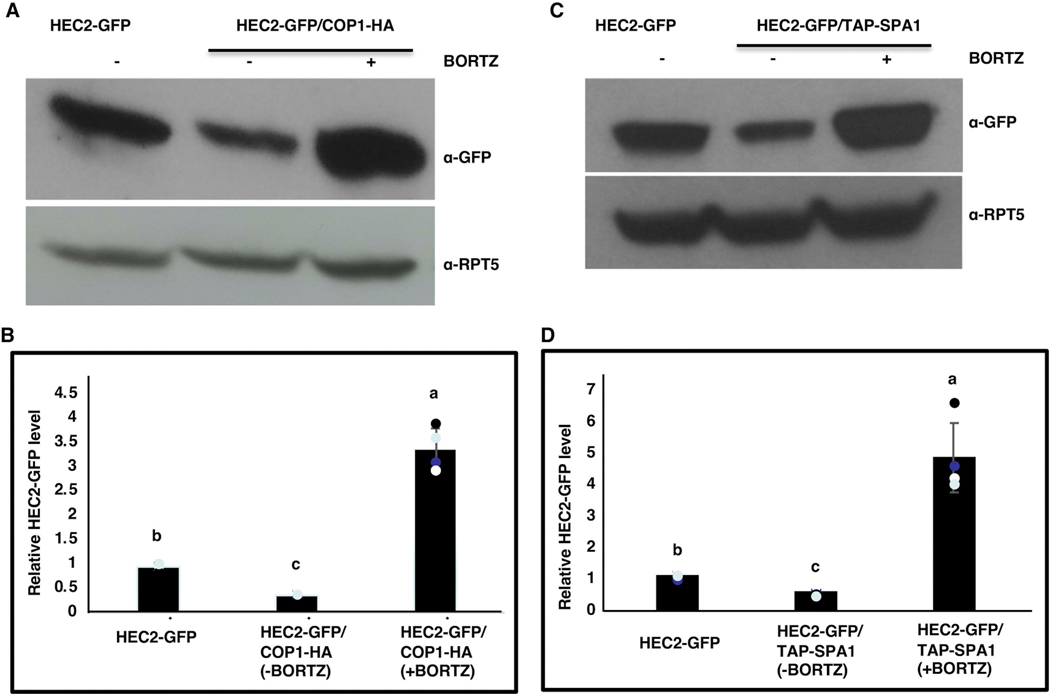

To further validate our hypothesis that the degradation of HECs in dark is indeed COP1 dependent, HEC2-GFP protein abundance was compared between etiolated seedlings of HEC2-GFP and HEC2-GFP/35S:COP1-HA double transgenic lines with and without the proteasome inhibitor (Bortezomib) treatment. It was observed that the HEC2-GFP protein abundance was significantly lower in HEC2-GFP/35S:COP1-HA than in HEC2-GFP seedlings (Figure 2A, B). However, treatment with the proteasome inhibitor resulted in increased abundance of HEC2-GFP in the double transgenic line, suggesting that overexpression of COP1 promotes the degradation of HEC2-GFP through the proteasome pathway. Collectively, these data indicate that, in darkness, both COP1 and PIFs synergistically regulate the abundance of HECs posttranslationally.

Figure 2: Overexpression of COP1-HA and TAP-SPA1 promotes the degradation of HEC2-GFP through the 26S proteasome-mediated pathway in the dark.

(A and C) Immunoblots showing HEC2-GFP protein accumulation in the HEC2-GFP and HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA (A) or HEC2-GFP and HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1 (C) double transgenic lines, respectively, with and without proteasome inhibitor (40 μM Bortezomib (BORTZ), 3hrs) treatment. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 4 days. Total protein was separated on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, blotted onto PVDF membrane and probed with anti-GFP or anti-RPT5 antibodies. (B and D) Bar graphs show the HEC2-GFP protein levels in seedlings of the corresponding genotypes. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n=3). The letters “a” to “c” indicate statistically significant differences between means of relative protein levels among the genotypes based on one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (p<0.05).

SPA proteins associate with COP1 to promote the degradation of several COP1 substrates (such as HY5, HFR1, and LAF1) to suppress plant photomorphogenesis (Saijo et al., 2003, Seo et al., 2003). To test if SPA proteins are necessary for HECs degradation in the dark, HEC2-GFP protein abundance was determined in etiolated seedlings of HEC2-GFP and spaQ/HEC2-GFP. Similar to cop1 mutant, HEC2-GFP protein abundance was significantly higher in spaQ/HEC2-GFP than in HEC2-GFP background (Supplementary figure S2A, B). Furthermore, HEC2-GFP protein abundance was significantly lower in the HEC2-GFP/35S:TAP-SPA1 double transgenic line compared to HEC2-GFP seedlings (Figure 2C, D). Moreover, treatment with the proteasome inhibitor resulted in increased abundance of HEC2-GFP in the double transgenic line, suggesting that TAP-SPA1 promotes the degradation of HEC2-GFP through the proteasome pathway. These data further support our hypothesis that COP1-PIFs-SPA complex synergistically regulate the HECs protein stability in etiolated seedlings.

PIFs promote COP1-mediated HEC2 degradation in a polyubiquitylation-dependent manner in vivo and in vitro.

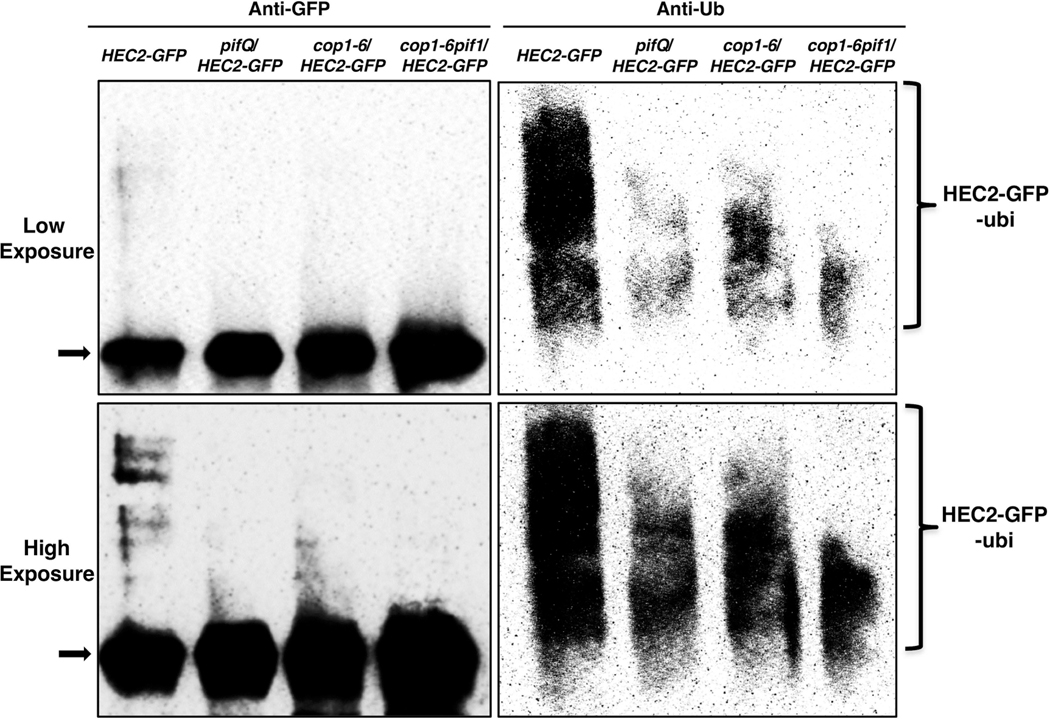

Since HEC2 protein was found to be significantly stable in pifQ, cop1–6, cop1–6/pif1 and also in spaQ backgrounds, and as HEC2 degradation can be blocked by proteasome inhibitor treatment (Zhu et al., 2016), we examined whether HEC2 is also ubiquitylated in vivo, in SPA-, COP1- and PIFs-dependent manner. HEC2-GFP protein was immunoprecipitated from etiolated seedlings of HEC2-GFP, pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP, and cop1–6pif1/HEC2-GFP, pretreated with proteasome inhibitor (Bortezomib) and probed with anti-GFP and anti-Ub antibodies. Similar to our earlier observation by immunoblots, HEC2-GFP level as detected by anti-GFP antibodies, was found to be significantly higher in pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP, and cop1–6pif1/HEC2-GFP than that in the HEC2-GFP (Figure 3, left panel). However, ubiquitylation levels of the immunoprecipitated HEC2-GFP as detected by anti-Ub antibodies, are significantly reduced in the pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP, and cop1–6pif1/HEC2-GFP than that in the HEC2-GFP (Figure 3, Right panel). Moreover, ubiquitylation of HEC2-GFP is also reduced in the spaQ background compared to wild type (Supplementary figure S3). Higher abundance of HEC2 protein and corresponding lower levels of ubiquitylation in etiolated seedlings of pifQ, cop1–6, cop1–6/pif1, and spaQ supports of our initial hypothesis that the ubiquitylation and degradation of HEC2 (and possibly other HECs) is COP1 and SPA-dependent, and that the PIF1 (and possibly other PIFs) promote HEC2 ubiquitylation and degradation via the 26S proteasome pathway in darkness.

Figure 3: PIF1 promotes HEC2 degradation in a ubiquitylation-dependent manner in vivo.

The protein level of HEC2-GFP is higher but the ubiquitylation level of HEC2-GFP is lower in the pifQ, cop1–6, and cop1–6pif1 compared with HEC2-GFP background in darkness. Total protein was extracted from 4-day-old dark grown seedlings pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor (40 mM Bortezomib) for 3 hours before protein extraction. HEC2-GFP was immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP antibody (rabbit) from protein extracts prepared using 4-d-old dark-grown seedlings. The immunoprecipitated samples were then separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels and probed with anti-GFP (left, Mouse) or anti-Ub (right) antibodies. Top panel is lower exposure, bottom panel is higher exposure. Arrow indicates the HEC2-GFP protein.

HEC1 and HEC2 physically interact with COP1 and SPA1.

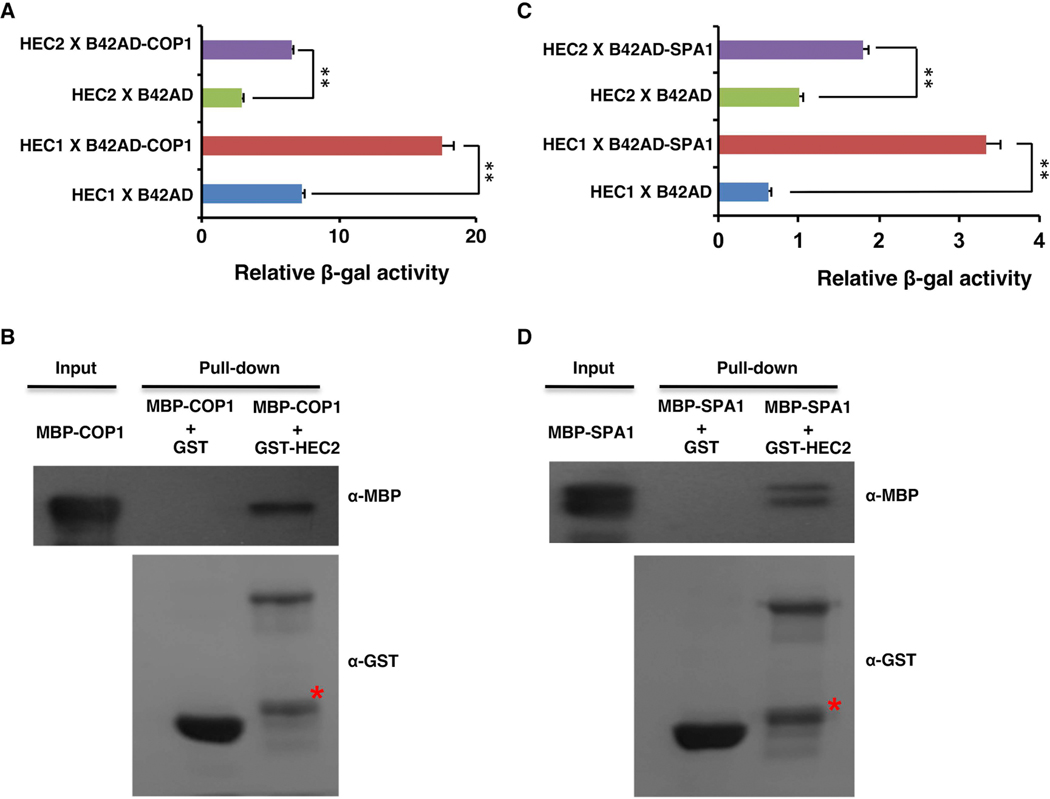

Since, HEC2-GFP protein abundance was significantly higher in etiolated seedlings of cop1, pifQ and spaQ, and also the fact that ubiquitylation was significantly lower in pifQ and cop1 mutant backgrounds, we examined if HECs physically interact with COP1 and SPA proteins similar to HEC2-PIF1 interaction shown previously (Zhu et al., 2016). Yeast two-hybrid assay shows that both HEC1 and HEC2 interact with both COP1 and SPA1 (Figure 4A, C). Moreover, in vitro pull-down assays using purified proteins from bacterial expression system showed that GST-HEC2, but not GST alone, can pull-down MBP-COP1 and MBP-SPA1 in vitro (Figure 4B, D). These data suggest that HEC2 can directly interact with COP1 and SPA1.

Figure 4: HEC1 and HEC2 physically interact with COP1 and SPA1 in yeast and in vitro.

(A and C) B42AD-COP1 (A) and B42AD-SPA1 (C) interact with both LexA-HEC1 and LexA-HEC2 in yeast-two-hybrid assays. Bar graph shows the average β-galactosidase activities from three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation, (n=3). ** indicate p value < 0.01, two-tailed student’s t-test.

(B and D) GST-HEC2 interacts with MBP-COP1 (B) and MBP-SPA1 (D) in vitro. GST, GST-HEC2, MBP-COP1 and MBP-SPA1 were expressed and purified from E. coli. Glutathione agarose bound GST or GST-HEC2 were used to pull-down equal amount of purified MBP-SPA1 or MBP-COP1 protein. Pull-down samples were loaded into the 8% SDS polyacrylamide gel followed by immunoblotting. The precipitated MBP-COP1 or MBP-SPA1 were detected by the anti-MBP antibody and the control blot was probed with anti-GST antibody. Red stars indicate non-specific band.

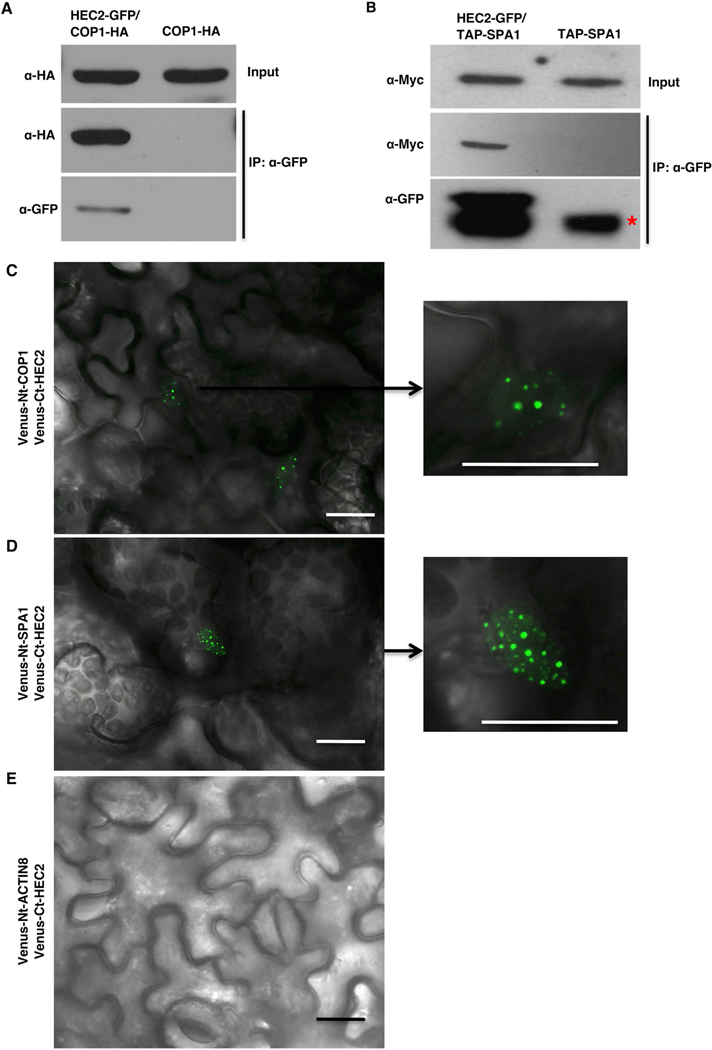

To examine if HEC2 can interact with COP1 and SPA1 in vivo, we performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays using crude protein extracts isolated from etiolated seedlings of COP1-HA vs HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA and TAP-SPA1 vs HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1, pretreated with proteasome inhibitors. Immunoprecipitation of HEC2-GFP with anti-GFP antibody and subsequent blotting with anti-HA and anti-myc antibodies showed that HEC2-GFP robustly interacts with COP1-HA and TAP-SPA1 in darkness (Figure 5A, B). In addition, we performed bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays using two halves of Venus fluorescent protein fused to HEC2 and COP1 or SPA1. Transient expression of Venus-Ct-HEC2 along with Venus-Nt-COP1 or Venus-Nt-SPA1 in tobacco leaves resulted in reconstitution of fluorescence in nucleus, while the control leaf expressing Venus-Ct-HEC2 and Venus-Nt-ACTIN8 did not display any fluorescence (Figure 5C-E). Moreover, expression of Venus-Ct-HEC2 along with Venus-Nt-COP1 or Venus-Nt-SPA1 resulted in formation of nuclear speckles characteristic of COP1 and SPA1 nuclear speckles as previously observed (Wang et al., 2001, Lu et al., 2015). Overall, these data further support the idea that HECs are part of the same complex as COP1-SPA1-PIFs and perhaps coordinately regulates the skotomorphogenic growth in Arabidopsis.

Figure 5: HEC2 interacts with COP1 and SPA1 in vivo.

(A and B) HEC2 interacts with COP1 and SPA1 in vivo. Four-day-old dark-grown seedlings of COP1-HA and HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA (A) or TAP-SPA1 and HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1 (B) were treated with proteasome inhibitor (40 μM Bortezomib) for 4hrs to block the HEC2 degradation before protein extraction. Co-IP was carried out using the anti-GFP antibody and then probed with anti-GFP and anti-HA or anti-myc antibodies.

(C and D) HEC2 interacts with COP1 and SPA1 in bimolecular fluorescence assays in Nicotiana benthamiana: Venus-Ct-HEC2 interacts with Venus-Nt-COP1 (C) and Venus-Nt-SPA1 (D) in nuclear speckles. (E) Venus-Ct-HEC2 does not interact with Venus-Nt-ACTIN8. Fusion genes were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana by infiltrating them with Agrobacterium strain GV3101 containing appropriate binary vectors. Confocal images were acquired 48–60 hours after the infiltration. Plants were transferred to dark chambers at least 12 hours before imaging. Scale bar = 20 μm.

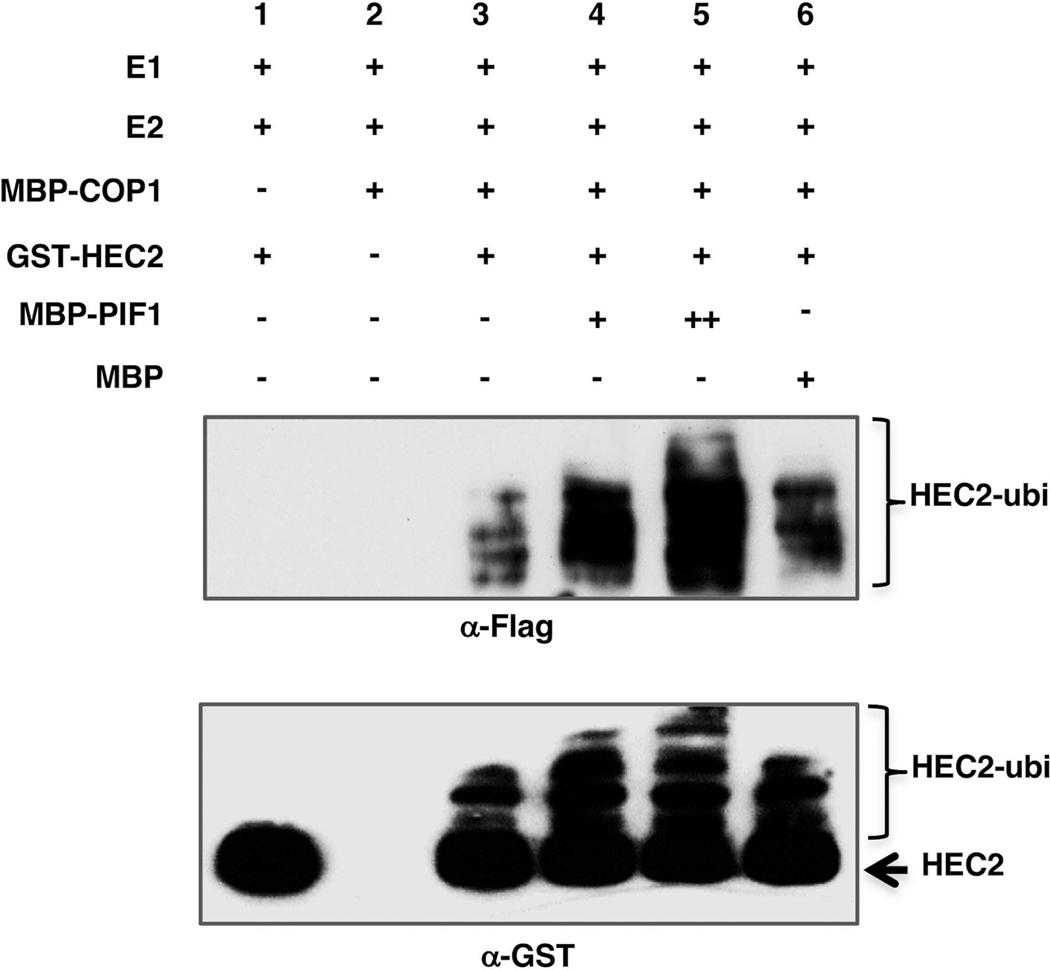

COP1 directly ubiquitylates HEC2 in vitro and PIF1 promotes the trans-ubiquitylation activity of COP1.

To test whether COP1 can directly ubiquitylate HEC2, we performed in vitro ubiquitylation assay using bacterially purified MBP-COP1 as the E3 Ubiquitin ligase and GST-HEC2 as the substrate in the presence of Flag-Ubiquitin, UBE1 (E1), and UbcH5b (E2). The results show that HEC2 was ubiquitylated in the presence of COP1 as detected by anti-GST and anti-Flag antibodies (Figure 6, lanes 1–3). In addition, we have previously shown that PIF1 promotes the degradation of COP1 substrate by enhancing the trans-ubiquitylation activity of COP1 toward the substrates (Xu et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2017). To test whether this was also the case with HEC2, we further performed the in vitro ubiquitylation assay using GST-HEC2, MBP-COP1 and different amounts of MBP-PIF1 or MBP as a control. Results showed that, in the presence of PIF1, the levels of HEC2 ubiquitylation were significantly increased in a PIF1 concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6, lanes 4–5). In contrast, the addition of the MBP control protein did not affect the COP1-mediated ubiquitylation of HEC2 (Figure 6, lane 6). Moreover, the level of ubiquitylation of HEC2 was lower in the pifQ background compared to HEC2-GFP in vivo (Figure 3). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that HEC2 is directly targeted by the E3 Ubiquitin ligase COP1 for ubiquitylation, and that this ubiquitylation is enhanced by PIF1 both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 6: COP1 directly ubiquitylates HEC2 in vitro and PIF1 promotes the trans-ubiquitylation activity of COP1.

Recombinant MBP-COP1, MBP-PIF1 and GST-HEC2 fusions proteins were purified from E. coli. In vitro Ubiquitylation assay was performed using MBP-COP1 as E3, Flag-Ubiquitin, UBE1 (E1), UbcH5b (E2), GST-HEC2 and increasing concentrations of MBP-PIF1. MBP was used as a control. (Top panel) Ubiquitylated GST-HEC2 detected by anti-Flag antibody. (Bottom panel) Ubiquitylated GST-HEC2 detected by anti-GST antibody. Arrow indicates non-ubiquitylated GST-HEC2.

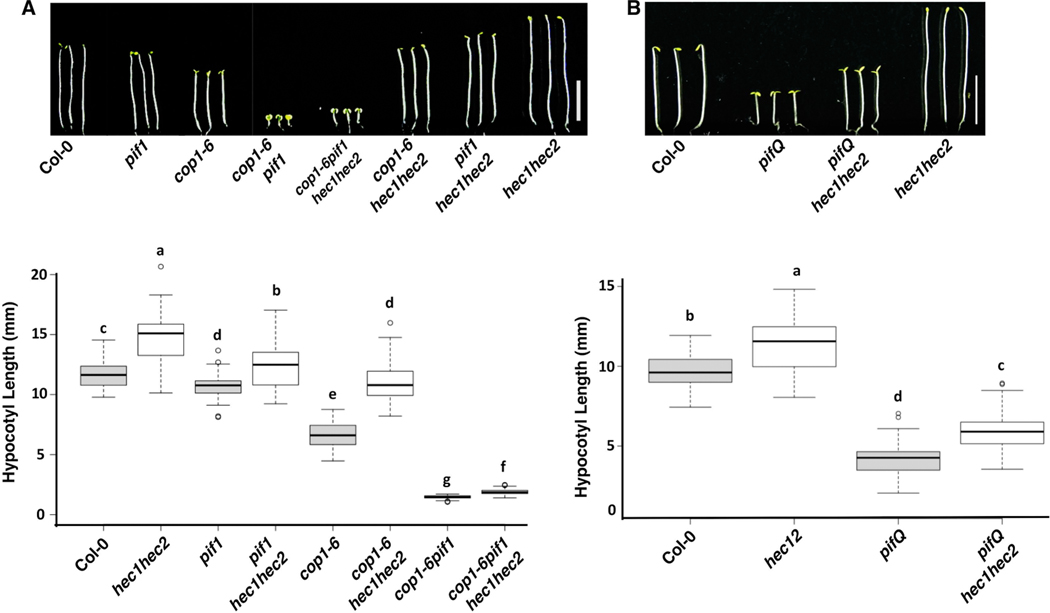

hec1hec2 partially suppress the constitutive photomorphogenic phenotypes of cop1–6pif1 and pifQ

Recently, we have shown that HECs are a new group of positive regulators for plant photomorphogenesis (Zhu et al., 2016). We have also shown that cop1pif mutant combinations synergistically promote photomorphogenesis by degrading the positive regulators HY5 and HFR1 (Xu et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2017). To study whether hec1 and hec2 can suppress this COP1-PIF synergistic photomorphogenesis effects, we created cop1–6hec1hec2, pif1hec1hec2 and cop1–6pif1hec1hec2 higher order mutants and compared hypocotyl lengths of these lines with that of their corresponding parental lines. It was observed that the hec1hec2 partially suppressed the photomorphogenic effect of cop1–6 and cop1–6pif1 double mutants (Figure 7A).

Figure 7: hec1 hec2 partially suppressed the photomorphogenic phenotype of cop1-6 pif1 and pifQ mutants.

(A) (Top) Photographs of seedlings of wild type, pif1, cop1-6, cop1-6pif1, cop1-6pif1hec1hec2, cop1-6hec1hec2, pif1hec1hec2 and hec1hec2 mutants. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 5 days. (Bottom) Box plot shows the hypocotyl lengths of various genotypes as indicated. (B) (Top) Photographs of seedlings of wild type, pifQ, pifQhec1hec2 and hec1hec2. Seedlings are grown in the dark for 5 days. Scale bar = 5mm. (Bottom) Box plot shows the hypocotyl lengths of various genotypes as indicated. Box plots were generated by BoxPlotR, center lines show the medians, box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. n > 90 sample points per genotype. The letters “a” to “f” indicate statistically significant differences between means of hypocotyl lengths among the genotypes based on one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD (p<0.05).

In agreement with the PIFs role as negative regulators of photomorphogenesis, pifQ mutants exhibit constitutive photomorphogenic responses, similar to those of cop1 (Leivar et al., 2008, Shin et al., 2009). To test if HECs function downstream of PIFs, we created pifQhec1hec2 sextuple mutant. Analyses of the hypocotyl length showed that hec1hec2 significantly suppressed the constitutive photomorphogenic phenotypes of pifQ (Figure 7B), similar to the cop1 mutant described above. All together these phenotypic analyses along with biochemical and molecular evidences strengthens the idea that HECs are indeed positive regulators of photomorphogenesis, and their abundance in etiolated seedlings is directly regulated by COP1-SPA-PIFs complex, which in-turn drive the optimal skotomorphogenic growth of plants.

DISCUSSION

In this study we provide strong molecular, biochemical and genetic evidences to support the notion that HECs are substrate of COP1-SPA E3 ligase and that the COP1-SPA-PIFs-HECs regulatory module determines the skotomorphogenic status of etiolated seedlings in Arabidopsis.

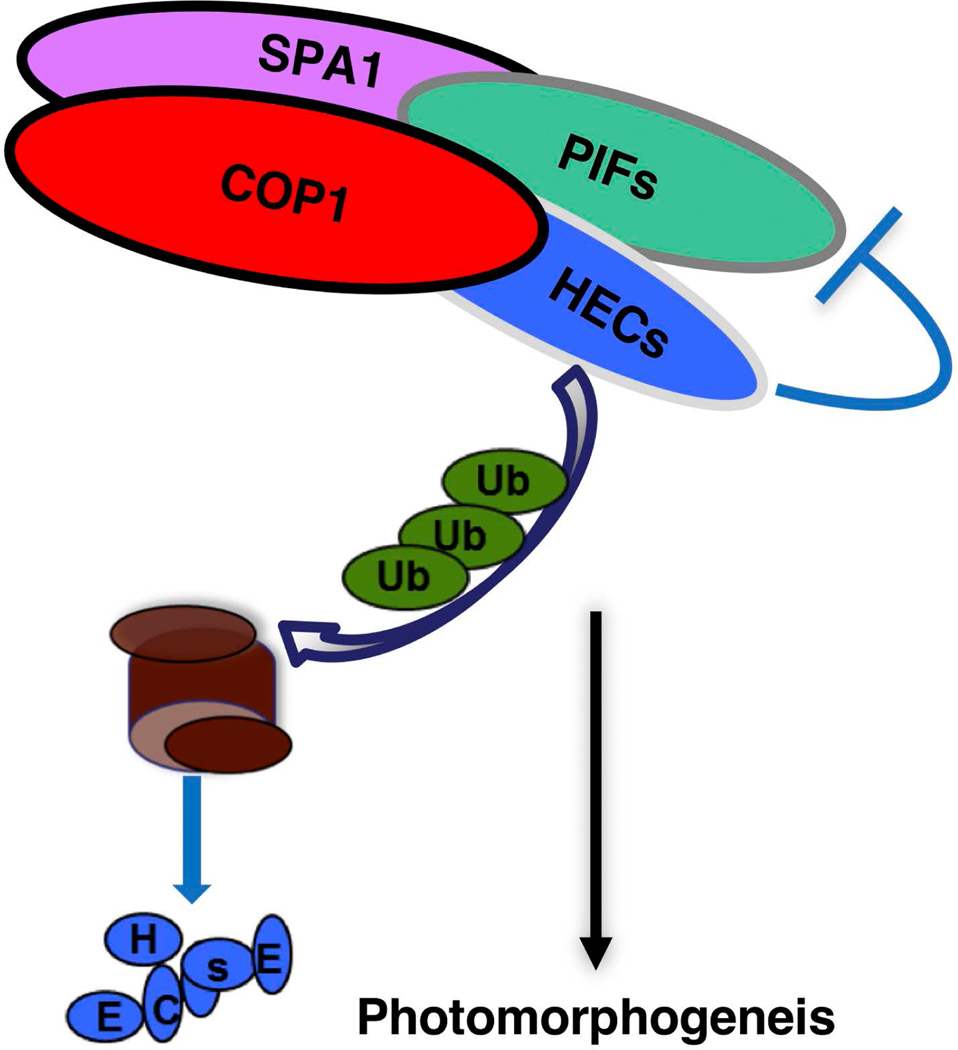

COP1, SPA and PIFs are well-established negative regulators of photomorphogenesis (Leivar and Quail, 2011, Lau and Deng, 2012, Xu et al., 2015, Pham et al., 2018a). HEC genes, which encode bHLH transcription factors, were initially identified because of their key role in the formation of the female reproductive tract in Arabidopsis gynoecia (Gremski et al., 2007, Crawford and Yanofsky, 2011), and more recently were found to be important players in modulation of hormone signaling, cell fate transition and photomorphogenesis (Schuster et al., 2015, Zhu et al., 2016, Gaillochet et al., 2017, Gaillochet et al., 2018). Our molecular, biochemical and genetic data support a model wherein COP1, PIFs and SPAs synergistically regulate photomorphogenesis by controlling the protein abundance of HEC2 (and possibly other HECs) via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome degradation pathway (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Schematic model for the COP1-PIF-HEC module regulating light signaling.

PIF1, COP1, SPA1 and HEC2 directly interact with each other to form a complex. During photomorphogenesis, HECs are a group of positive regulators that are targeted by COP1 Ubiquitin E3 ligase for degradation in the dark. PIF1 promotes COP1-mediated ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of HEC2 through the 26S proteasome pathway. HECs also antagonize PIF activity to promote plant photomorphogenesis.

As previously reported cop1pif1 and pifQ mutants show constitutive photomorphogenic responses in the dark (Xu et al., 2014). Here we show that the constitutive photomorphogenic phenotype observed in these mutants is subtly dependent on HECs, as mutations in hec genes partially suppress the photomorphogenic phenotypes of cop1–6pif1 and pifQ mutant seedlings growing in the dark (Figure 7). These genetic data strongly suggest that HECs function downstream of COP1 and PIFs during photomorphogenesis.

Our biochemical assays strongly suggest that HEC2 is a substrate for the E3 Ubiquitin ligase COP1. First, HEC2-GFP protein level is more abundant in the pif1, cop1–6, pifQ, cop1–6 pif1 and spaQ, compared to HEC2-GFP in wild-type (Figures 1A-B, Supplementary Figure S2A-B). Conversely, overexpression of COP1 and SPA1 reduces the abundance of HEC2-GFP in the HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA and HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1 double transgenic plants, but it can be increased after treatment with the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Figure 2). Second, COP1, SPA1 and PIF1 directly interact with HEC2 in yeast-two-hybrid, in vitro and in vivo co-IP assays as well as BiFC assays (Figures 4, 5). Third, COP1 directly ubiquitylates HEC2 in the presence of the E1 and E2 enzymes in vitro. Moreover, this ubiquitylation is enhanced by the increasing concentration of PIF1 (Figure 6). Finally, HEC2 is ubiquitylated in the dark in a COP1 and SPA-dependent manner in vivo, and PIF1 (and possibly other PIFs) enhance the HEC2 ubiquitylation and degradation in vivo (Figure 3). These data are consistent with our previous report that HEC2 is degraded in the dark and is stabilized by light at the seedling stage (Zhu et al., 2016). This regulation is reminiscent of other COP1 substrates, HY5 and HFR1, which are also synergistically degraded by both COP1 and PIFs (Xu et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2017). Previously, we showed that PIF1 can enhance the interaction between COP1 and HY5 and thereby, stimulate the poly-ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of HY5 by COP1 (Xu et al., 2014). Therefore, it is possible that PIF1 (and possibly other PIFs) might enhance the affinity of COP1 toward HECs, and promote the trans-ubiquitylation of HEC2 by COP1 for the proteasome-mediated degradation under darkness. Overall, these data suggest that COP1, SPA and PIFs regulate seedling de-etiolation by directly regulating the abundance of HECs via ubiquitylation and subsequent protein degradation (Figure 8).

In conclusion, the COP1-SPA-PIF complexes play a pivotal role as an E3 Ubiquitin ligase complex in plants. COP1 is also present in many organisms including mammals, and plays crucial roles in mammalian tumorigenesis (Yi and Deng, 2005, Marine, 2012). In mammals, COP1 binds to its substrates either directly or indirectly through an adaptor protein called Trible, which is a pseudokinase. Recent crystal structure shows that both Arabidopsis and mammalian COP1 recruit substrates through the WD40 domain located at the carboxy terminus. In fact, Trible also interacts at the WD40 domain and function as a bridging protein to recruit C/EBP for degradation (Uljon et al., 2016). In Arabidopsis, SPA proteins have Ser/Thr kinase-like domains, and help COP1 to recruit substrates (Hoecker et al., 1999, Hoecker, 2017). Thus, plant and mammalian COP1 uses similar mechanisms to recruit substrates for ubiquitylation and degradation. Identification and characterization of more substrates in both plant and mammalian systems will help understand how COP1 plays key roles in diverse pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant materials, growth conditions and measurements

All plant materials used in this work were in the Col-0 background (Laubinger et al., 2004, Xu et al., 2014). The 35S:HEC2-GFP in wild type Col-0 background and hec1hec2 double mutants have been described earlier (Zhu et al., 2016). Through genotyping and phenotypic characterization, we identify the different mutant combinations used in this work. HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA and HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1 double transgenic plants were generated by crossing 35S:COP1-HA or 35S:TAP-SPA1 with 35S:HEC2-GFP. Primer sequences used for genotyping were described earlier (Schuster et al., 2014, Xu et al., 2014).

Plant growth conditions were same as previously described (Shen et al., 2005). Briefly, adult plants were grown in metro-Mix 200 soil (Sun Gro Horticulture, Bellevue, WA, USA) under constant light, short day, or long day conditions at 22°C. For seedling growth, seeds of various genotypes were surface sterilized and plated on Murashige-Skoog (MS) growth medium containing 0.9% agar. After stratification at 4°C for 4–5 days, plates were exposed to 3 h of white light at room temperature to induce germination. Plates were then placed in the dark at 21°C for 4–5 days for phenotypic analyses. Hypocotyl measurements were performed as previously described using the ImageJ software (Xu et al., 2014). Three biological repeats were performed for each genotype.

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR

The quantitative Real Time- PCR (qRT-PCR) assays were performed as previously described (Xu et al., 2014). Four-day-old dark-grown seedlings were frozen and powdered in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using the Spectrum plant total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). qRT-PCR was performed using the Power SYBR Green RT-PCR Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA). PP2A (At1g13320) was used as an internal control for normalization. The transcript abundance of HEC2-GFP was set to 1 and the relative values of other samples were calculated. Primer used for qPCR is listed in the Table S1.

Protein extraction and immunoblot analyses

For immunoblotting, same quantity of four-day-old dark-grown seedlings, either mock treated or treated with 40μM bortezomib for 3 hours, were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total protein was extracted in an extraction buffer (Xu et al., 2014) and centrifuged at 12,000Xg for 10 minutes to remove debris. Crude protein samples were separated onto 8–10% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blots were first probed with anti-GFP antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc, CA). Blots were then stripped and re-probed with anti-RPT5 antibody (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). To quantify the relative protein abundance of HEC2-GFP, band intensities of HEC2-GFP and RPT5, from at least three blots were measured by ImageJ. HEC2-GFP/RPT5 ratio was calculated for each of the samples and the value of HEC2-GFP in Col-0 was set to 1 and the relative values of other samples were calculated.

In vitro pull-down assays

To perform in vitro pull-down assays, bacterially expressed MBP-COP1 and MBP-SPA1 were first affinity purified using amylose resin (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and then eluted from beads using 10mM maltose containing buffer. GST and GST-HEC2 were purified using commercially available agarose-glutathione beads, following the commercial kit protocol (Thermofischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Approximately 1μg of purified MBP-COP1 or MBP-SPA1 were added to glutathione beads containing attached either GST or GST-HEC2, and tubes were incubated at 4°C in a rotator mixer for approximately 3 hours. After incubation, glutathione beads were pelleted by brief centrifugation and washed thoroughly at least 3 times. After final wash, beads were immersed in 1X- SDS buffer and boiled for 5 minutes. Proteins were separated on 4–12% gradient gel (Thermofischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). MBP-COP1 and MBP-SPA1 were detected using anti-MBP (Thermofischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA), while GST and GST-HEC2 were detected using anti-GST-HRP antibodies (GE Healthcare, Houston, TX).

In vivo co-immunoprecipitation assays

Four-day-old dark-grown COP1-HA, TAP-SPA1, HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA and HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1 transgenic seedlings were treated with 40 μmol bortezomib for 4 hrs in the dark (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA). Total protein was extracted with native extraction buffer (Zhu et al., 2015) and centrifuged at 12,000Xg for 15 min to remove cell debris. HEC2-GFP was immunoprecipitated with 1μg of Anti-GFP (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) conjugated to Dynabeads. Following immunoprecipitation, beads were washed three times with washing buffer (Native extraction buffer without bortezomib) and protein was eluted from beads, as described earlier (Zhu et al., 2015). Proteins were separated onto 8% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blots were initially probed with either anti-HA (for HEC2-GFP/COP1-HA; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or anti-Myc (for HEC2-GFP/TAP-SPA1; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) antibody. Blots were then stripped and re-probed with anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc, CA) antibody.

To detect ubiquitylation status of HEC2-GFP in dark-grown etiolated seedlings of HEC2-GFP, pifQ/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6/HEC2-GFP, cop1–6pif1/ HEC2-GFP and spaQ/HEC2-GFP, HEC2-GFP was immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP antibodies, as described above. Proteins were separated on 6.5% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to PVDF membrane. Blots were first probed with anti-Ub (Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX) antibody. Blots were then stripped and re-probed with anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc, CA) antibody.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays

For bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays, HEC2, COP1 and SPA1 open reading frames (ORF) were amplified using Phusion polymerase and primers listed in Table S1 and cloned into pENTR-D-TOPO® and pDONR221 vector following kit protocol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). pENTR-HEC2 vector was recombined with pDEST-VYCE® GW destination vector, while pENTR-COP1 and pDONR221-SPA1 were recombined into pDEST-VYNE® GW following kit protocol (Thermofischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Binary vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101. To perform BiFC assays, Agrobacterium strain GV3101 containing appropriate binary vectors were infiltrated in N. benthamiana following protocol described elsewhere (Kang et al., 2008). After infiltration, tobacco plants were incubated under continuous light for 36–48 hours and then transferred to dark chamber for 12 hours before acquiring confocal images.

In vitro ubiquitylation assays

HEC2 ORF was cloned into pGEX4T-1 vector. The MBP-PIF1, MBP-COP1 and GST-HEC2 proteins were purified from E.coli. UBE1 (E1), UbcH5b (E2), Flag-tagged ubiquitin (FlagUb) were commercially purchased (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA). The in vitro ubiquitylation assays were performed as described previously, however, with minor modifications (Zhao et al., 2013, Xu et al., 2014). Briefly, 5μg of Flag-Ubiquitin, ~25ng of E1, ~25ng of E2, ~500ng of MBP-COP1, ~300ng of GST-HEC2, and 50–100ng MBP-PIF1 were used in the reaction. The reaction buffer contains 50 mM Tris, pH7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, and 2 mM DTT. Reaction mixture was incubated for 2 hrs at 30°C. Reaction was attenuated by the addition of 1X SDS- sample buffer and boiling at 95°C for 5 minutes. Proteins were separated onto 6.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Blots were probed with Anti-GST-HRP conjugate (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) to detect GST-HEC2. Moreover, Blots were also probed with anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) antibody to detect ubiquitylated HEC2 protein.

Yeast two-hybrid analyses

Full-length ORFs of HEC1 and HEC2 were cut from GAD-HEC1 and GAD-HEC2 (Zhu et al., 2016) and were cloned into pEG202 (Ausubel et al., 1994) to generate LexA-HEC1 and LexA-HEC2. Preparation of AD-COP1 and AD-SPA1 were described previously (Xu et al., 2014, Zhu et al., 2015). The different combinations of these vectors were transformed into yeast EGY48–0 (Ausubel et al., 1994). Yeast growth, selection, induction and β-galactosidase activity assay was performed as described (Ausubel et al., 1994).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: HEC2 mRNA level in HEC2-GFP overexpression seedlings.

Figure S2: HEC2-GFP is more abundant in spaQ compared to Col-0 background.

Figure S3: SPA proteins promote HEC2 polyubiquitylation in vivo.

Table S1: Primer sequences used in experiments described in the text.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Xing Wang Deng for sharing the cop1 mutants and yeast constructs, Ute Hoecker for sharing the spaQ mutant, and Hong Qiao for BiFC vectors. We thank the Huq lab members for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-1543813) and National Institute of Health (NIH) (GM-114297) to E.H. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All relevant data can be found within the manuscript and its supporting materials and are also available from the corresponding author, Enamul Huq (huq@austin.utexas.edu), upon request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES:

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA and Struhl K. (1994) Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Suppl.). New York:: John Wiley and Sons; ), pp. 13.16.12–13.16.14. [Google Scholar]

- Casal JJ (2013) Photoreceptor signaling networks in plant responses to shade. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 64, 403–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford BCW and Yanofsky MF (2011) HALF FILLED promotes reproductive tract development and fertilization efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development, 138, 2999–3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillochet C, Jamge S, van der Wal F, Angenent G, Immink R. and Lohmann JU (2018) A molecular network for functional versatility of HECATE transcription factors. The Plant Journal, 95, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillochet C, Stiehl T, Wenzl C, Ripoll J-J, Bailey-Steinitz LJ, Li L, Pfeiffer A, Miotk A, Hakenjos JP, Forner J, Yanofsky MF, Marciniak-Czochra A. and Lohmann JU (2017) Control of plant cell fate transitions by transcriptional and hormonal signals. eLife, 6, e30135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremski K, Ditta G. and Yanofsky MF (2007) The HECATE genes regulate female reproductive tract development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development, 134, 3593–3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch M, Lorrain S, de Wit M, Trevisan M, Ljung K, Bergmann S. and Fankhauser C. (2014) Light intensity modulates the regulatory network of the shade avoidance response in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111, 6515–6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker U. (2017) The activities of the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA, a key repressor in light signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 37, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker U, Tepperman JM and Quail PH (1999) SPA1, a WD-repeat protein specific to phytochrome A signal transduction. Science, 284, 496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P, Lorrain S, Zoete V, Michielin O. and Fankhauser C. (2009) Inhibition of the shade avoidance response by formation of non-DNA binding bHLH heterodimers. Embo J, 28, 3893–3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Yang JY, Seo HS and Chua NH (2005) HFR1 is targeted by COP1 E3 ligase for post-translational proteolysis during phytochrome A signaling. Genes Dev, 19, 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HG, Kuhl JC, Kachroo P. and Klessig DF (2008) CRT1, an Arabidopsis ATPase that interacts with diverse resistance proteins and modulates disease resistance to Turnip Crinkle Virus. Cell Host Microbe, 3, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau OS and Deng XW (2012) The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci, 17, 584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger S, Fittinghoff K. and Hoecker U. (2004) The SPA Quartet: A Family of WD-Repeat Proteins with a Central Role in Suppression of Photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 16, 2293–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legris M, Ince YÇ and Fankhauser C. (2019) Molecular mechanisms underlying phytochrome-controlled morphogenesis in plants. Nature Communications, 10, 5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Oka Y, Liu T, Carle C, Castillon A, Huq E. and Quail PH (2008) Multiple phytochrome-interacting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photomorphogenesis in darkness. Curr Biol, 18, 1815–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P. and Quail PH (2011) PIFs: pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci, 16, 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L-J, Zhang Y-C, Li Q-H, Sang Y, Mao J, Lian H-L, Wang L. and Yang H-Q (2008) COP1-mediated ubiquitination of CONSTANS is implicated in cryptochrome regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell, 20, 292–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X-D, Zhou C-M, Xu P-B, Luo Q, Lian H-L and Yang H-Q (2015) Red-Light-Dependent Interaction of phyB with SPA1 Promotes COP1–SPA1 Dissociation and Photomorphogenic Development in Arabidopsis. Molecular Plant, 8, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Gao Y, Qu L, Chen Z, Li J, Zhao H. and Deng XW (2002) Genomic evidence for COP1 as a repressor of light-regulated gene expression and development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 14, 2383–2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marine J-C (2012) Spotlight on the role of COP1 in tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer, 12, 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez-Herrera N, Fackendahl P, Yu X, Schaefer S, Koncz C. and Hoecker U. (2015) A cop1 spa Mutant Deficient in COP1 and SPA Proteins Reveals Partial Co-Action of COP1 and SPA during Arabidopsis Post-Embryonic Development and Photomorphogenesis. Molecular Plant, 8, 479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N. and Deng XW (2000) Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature, 405, 462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik I, Chen F, Ngoc Pham V, Zhu L, Kim J-I and Huq E. (2019) A phyB-PIF1-SPA1 kinase regulatory complex promotes photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Nature Communications, 10, 4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham VN, Kathare PK and Huq E. (2018a) Phytochromes and Phytochrome Interacting Factors. Plant Physiology, 176, 1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham VN, Paik I, Hoecker U. and Huq E. (2020) Genomic evidence reveals SPA-regulated developmental and metabolic pathways in dark-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. Physiol Plantarum, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham VN, Xu X. and Huq E. (2018b) Molecular bases for the constitutive photomorphogenic phenotypes in Arabidopsis. Development, 145, dev169870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo Y, Sullivan JA, Wang H, Yang J, Shen Y, Rubio V, Ma L, Hoecker U. and Deng XW (2003) The COP1-SPA1 interaction defines a critical step in phytochrome A-mediated regulation of HY5 activity. Genes Dev, 17, 2642–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster C, Gaillochet C. and Lohmann JU (2015) Arabidopsis HECATE genes function in phytohormone control during gynoecium development. Development, 142, 3343–3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster C, Gaillochet C, Medzihradszky A, Busch W, Daum G, Krebs M, Kehle A. and Lohmann JU (2014) A Regulatory Framework for Shoot Stem Cell Control Integrating Metabolic, Transcriptional, and Phytohormone Signals. Developmental Cell, 28, 438–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo HS, Yang JY, Ishikawa M, Bolle C, Ballesteros ML and Chua NH (2003) LAF1 ubiquitination by COP1 controls photomorphogenesis and is stimulated by SPA1. Nature, 423, 995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Moon J. and Huq E. (2005) PIF1 is regulated by light-mediated degradation through the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway to optimize seedling photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J, 44, 1023–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Zhong S, Mo X, Liu N, Nezames CD and Deng XW (2013) HFR1 Sequesters PIF1 to Govern the Transcriptional Network Underlying Light-Initiated Seed Germination in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell, 25, 3770–3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Kim K, Kang H, Zulfugarov IS, Bae G, Lee CH, Lee D. and Choi G. (2009) Phytochromes promote seedling light responses by inhibiting four negatively-acting phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U S A, 106, 7660–7665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uljon S, Xu X, Durzynska I, Stein S, Adelmant G, Marto, Jarrod A, Pear, Warren S. and Blacklow, Stephen C. (2016) Structural Basis for Substrate Selectivity of the E3 Ligase COP1. Structure, 24, 687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ma L-G, Li J-M, Zhao H-Y and Deng XW (2001) Direct Interaction of Arabidopsis Cryptochromes with COP1 in Light Control Development. Science, 294, 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Kathare PK, Pham VN, Bu Q, Nguyen A. and Huq E. (2017) Reciprocal proteasome-mediated degradation of PIFs and HFR1 underlies photomorphogenic development in Arabidopsis. Development, 144, 1831–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Paik I, Zhu L, Bu Q, Huang X, Deng XW and Huq E. (2014) PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR1 Enhances the E3 Ligase Activity of CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 to Synergistically Repress Photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 26, 1992–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Paik I, Zhu L. and Huq E. (2015) Illuminating Progress in Phytochrome-Mediated Light Signaling Pathways. Trends in plant science, 20, 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lin R, Sullivan J, Hoecker U, Liu B, Xu L, Deng XW and Wang H. (2005) Light Regulates COP1-Mediated Degradation of HFR1, a Transcription Factor Essential for Light Signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 17, 804–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C. and Deng XW (2005) COP1 - from plant photomorphogenesis to mammalian tumorigenesis. Trends in Cell Biology, 15, 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J-W, Rubio V, Lee N-Y, Bai S, Lee S-Y, Kim S-S, Liu L, Zhang Y, Irigoyen ML and Sullivan JA (2008) COP1 and ELF3 control circadian function and photoperiodic flowering by regulating GI stability. Molecular cell, 32, 617–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Tian M, Li Q, Cui F, Liu L, Yin B. and Xie Q. (2013) A plant-specific in vitro ubiquitination analysis system. The Plant Journal, 74, 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu DM, Maier A, Lee J-H, Laubinger S, Saijo Y, Wang HY, Qu L-J, Hoecker U. and Deng XW (2008) Biochemical Characterization of Arabidopsis Complexes Containing CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 and SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA Proteins in Light Control of Plant Development. Plant Cell, 20, 2307–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Bu Q, Xu X, Paik I, Huang X, Hoecker U, Deng XW and Huq E. (2015) CUL4 forms an E3 ligase with COP1 and SPA to promote light-induced degradation of PIF1. Nature communications, 6, 7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Xin R, Bu Q, Shen H, Dang J. and Huq E. (2016) A negative feedback loop between PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTORs and HECATE proteins fine tunes photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 28, 855–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: HEC2 mRNA level in HEC2-GFP overexpression seedlings.

Figure S2: HEC2-GFP is more abundant in spaQ compared to Col-0 background.

Figure S3: SPA proteins promote HEC2 polyubiquitylation in vivo.

Table S1: Primer sequences used in experiments described in the text.