Highlights

-

•

Cervical lymph nodes are a common site of metastases for malignant tumors, most commonly developed from head and neck primary tumors.

-

•

Isolated supraclavicular lymph nodes should alert the clinician to consider non head and neck primary neoplasm.

-

•

Careful clinical examination, imaging tools and pathological analysis are necessary to establish an early diagnosis for adequate treatment.

Keywords: Supraclavicular lymph node, Lymph node metastases, Distant primary tumor

Abstract

Cervical lymph nodes are a common site of metastases for malignant tumors, most commonly developed from head and neck primary tumors. But, they can also be secondary to distant primary tumors.

We report the case of two patients treated in our Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck department for chronic supraclavicular lymphadenopathies, for whom further investigations showed lymph node metastasis originating from distant tumors.

Thus, careful clinical examination, imaging tools, and if possible pathological analysis are necessary to establish an early diagnosis for adequate treatment.

1. Introduction

Cervical lymph nodes are a common site of metastases for malignant tumors, most commonly developed from the upper aero digestive tract malignancies. Apart from these last, thyroid cancers and skin cancers of the head and neck region may present as cervical nodal metastasis [1]. Indeed, lymphoma and tuberculosis also manifest by cervical lymph nodes; thereby, they always should be taken into consideration as a differential diagnosis [2]. In fact, about 1% of all head and neck malignancies are accounted for by metastases from a remote primary site, including mostly the breast, lung, gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts, and, uncommonly, the central nervous system [3].

We report two cases treated in our Otorhinolaryngology and Head and Neck department for chronic supraclavicular lymphadenopathies, for whom further investigations showed lymph node metastasis originating from distant tumors. These case reports supplement and support the literature exposing the necessity of careful and multiple investigations in order to establish an early diagnosis for adequate treatment

2. Case report 1

We report the case of an 80 year old female patient, under treatment for hypertension, hyperuricemia and moderate renal failure, operated 8 years ago for pacemaker implantation. The patient had been operated in 2018 for malignant parotid tumor undergoing a total parotidectomy with lymph node dissection of the IIA and IIB levels. Pathological examination of the surgical piece showed myoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland with capsular invasion measuring 5 * 2 cm, 3 N + / 12 N lymph node metastasis and presence of vascular emboli. Then, the patient received 30 sessions of adjuvant radiotherapy.

The patient was admitted in our department for isolated chronic supraclavicular lymphadenopathy evolving since a year.

Clinical examination found a fixed left supraclavicular mass, firm and painless at palpation measuring approximately 4 cm. The patient had a performance status quoted to 4 and presented also a left facial palsy graded as 6 according to House-Brackmann classification secondary to her former parotid cancer (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Left supraclavicular mass (Arrow).

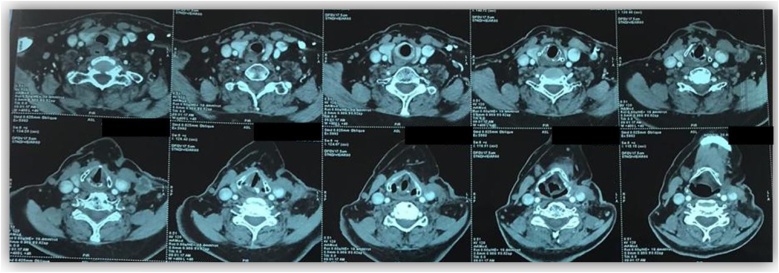

Cervical CT scan showed a left supraclavicular mass directly related to the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle with peripheral enhancement, most likely of lymph node origin. The parotid area was free with no abnormal contrast enhancement (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Cervical CT scan. (Axial sections).

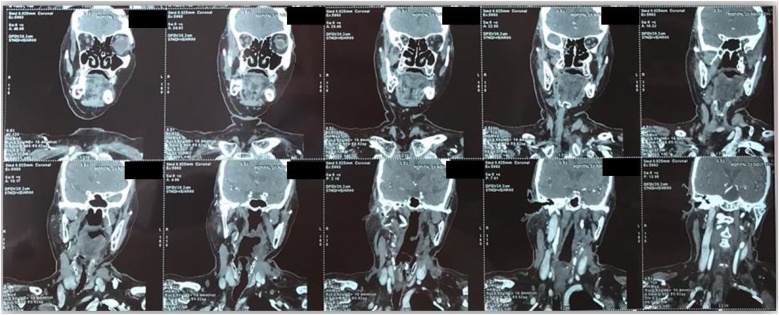

Fig. 3.

Cervical CT scan. (Frontal sections).

After normal endoscopic examination of the rhinopharynx, biopsy of the mass under local anesthesia was performed.

Histological examination of the pieces showed carcinomatous proliferation arranged in cords. The tumor cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm and strongly atypical hyperchromatic nuclei. They expressed diffusely CYTOKERATIN (CK) 7; however, they didn’t express P40, PS100 or CK 20. Indeed, this immunophenotyping was not in favor of myoepithelial carcinoma, indicating complementary analysis, which showed poorly differentiated and infiltrating CK7 + / CK20 / RE + carcinoma, concluding to gynecologic of breast origins first.

The patient was referred to the gynecology department for further adequate management.

3. Case report 2

We present the case of a 60 year old patient, with medical history, consulted in our department for chronic cervical lymphadenopathies evolving since a year and a half. No fever, no digestive of respiratory signs were reported.

Clinical examination found multiple left lymphadenopathies, mobile, painless and firm at palpation. The most voluminous one is located in the left supraclavicular fossa measuring 3,5 cm (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Left supraclavicular mass (Arrow).

Cervical CT scan examination showed multiple large left lymph nodes, located in the inferior level of the neck, the largest one measuring 38*24 cm and pushing forward the internal jugular vein and the SCM muscle.

After normal endoscopic examination of the rhinopharynx, total lymphadenectomy of the largest node was performed under local anesthesia.

Histological examination of the piece showed tumor proliferation. The immunophenotyping showed that the tumor cells weakly express CK AE1AE and strongly express synaptophysin and chromogranin. Thus, this analysis concluded to a lymph node metastasis of a neuroendocrine tumor of undetermined localization.

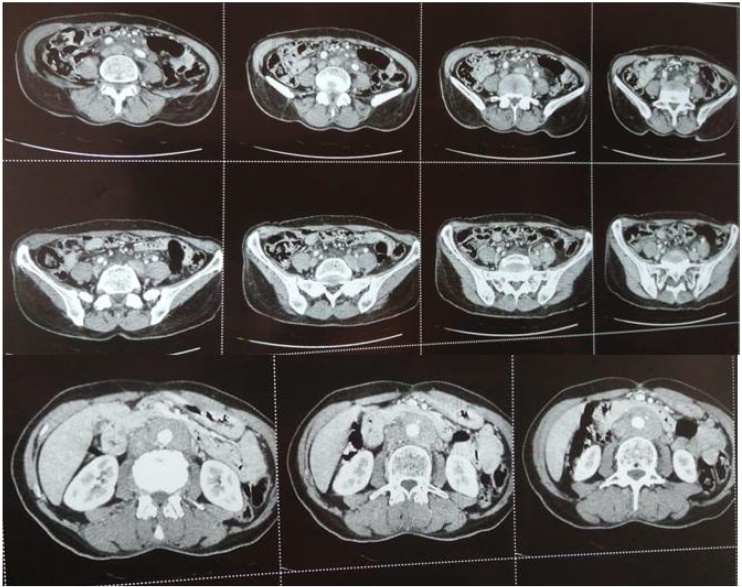

As complement of investigation, the patient underwent Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan coupled with CT scan, showing intense hyper metabolic lymph node involvement in cervical, mediastinal and abdomino-pelvic areas, in addition to hyper metabolic anal mass with a volume estimated to 19.36 cm3 associated to satellite lymphadenopathies, as well as hyper metabolic left pleural thickening of visceral and parietal layers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Abdomino-pelvic CT scan (Axial sections) showing the mass surrounding the abdominal aorta.

The patient was referred to Oncology department for further adequate treatment and management.

These two cases were reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [4].

4. Discussion

Cervical lymph node metastases are most commonly developed from oral cavity malignancies. Also, squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aero digestive tract, salivary glands malignancies, thyroid cancers and skin cancers of the head and neck region can also present cervical nodal metastasis [5].

However, cervical nodal metastases, in absence of obvious clinical primary tumor of the head and neck area, should alarm clinicians to suspect distant primary cancer. Indeed, early prompt diagnosis evaluation of these patients will amend the prognosis to some extent. In fact, incidence of neck node metastasis from distant primary site is accounting about 1%, including breast, lung, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract and rarely central nervous system malignancies [6].

Since lymphatic flow towards the left neck begins in the superior mediastinum, left supraclavicular lymph nodes receive lymphatic drainage from the thorax, abdomen and pelvis [7]. Being located in the draining path of the thoracic duct explains the possibility of metastasis of abdominal and pelvic neoplasms in left supraclavicular lymph nodes. In the literature, a report from Ismi et al. about 18 cases confirmed that the lung was the most common cause of supraclavicular lymph node metastasis, with only one case originating from the stomach [8]. As for Cervin et al., Gupta et al., and Nasuti et al., all found that supraclavicular lymph node metastases are more commonly caused by breast and lung tumors [[9], [10], [11]]; while Mitra et al. discribed a metastasis rate of 79.7% in supraclavicular lymph nodes mostly originating from lung squamous cell carcinomas in about 41.1% of the cases [12].

In other studies, other localizations were mentioned such as genitourinary neoplasms. However, the rest of metastatic cervical lymph nodes are usually affected by squamous cell carcinoma from the head and neck region or thyroid carcinomas [13].

Also, the age of the patient should always be taken into account. Metastatic malignant tumors are often seen after 50 years [14]. Actually, cervical lymph nodes in younger patients are usually reactive lymphadenitis [15], and the hematologic malignancies are much more common in pediatric patients than in adults [16].

Though, before proceeding to biopsy, a careful examination of the rhino pharynx, nasal cavities and mouth is indicated because in 90% of the cases, the primary lesion can be found there. The 10% remaining will develop a clinically obvious lesion in the future [17]. In this case, further examinations are indicated in order to look for a primary tumor, as well as a regular check and follow up in case of negative results. This report illustrates the importance of a thorough history and physical examination and regular cancer screening when evaluating a case of metastasis of an unknown primary origin [18].

As for the complementary diagnosis tools, immunophenotyping and molecular tests have been widely employed in cases with unknown primary neoplasms to guide the clinical and imaging search for clinicians, while relying on clinical and epidemiological features, which can be extremely helpful [19].

5. Conclusion

Although most metastatic neck nodes arise from primary tumors of the head and neck area, an isolated supraclavicular lymph node should alert the clinician to consider the likely possibility of a non head and neck primary neoplasm.

Henceforth, we would like to highlight the importance of thorough assessment examination based on a careful clinical examination, imaging tools, and if possible pathological analysis. All required, to establish a correct diagnosis, as well as to evaluate the patient and adapt an appropriate and adequate treatment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been exempted by our institution.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Oukessou Youssef: Study concept.

Hammouda Yassir: Study concept and writing the paper.

El Bouhmadi Khadija: Corresponding author and writing the paper.

Rouadi Sami: Study concept.

Abada Redallah Larbi: Correction of the paper.

Mahtar Mohamed: Correction of the paper.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr Hammouda Yassir.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Hematpour K., Bennett C.J., Rogers D., Head C.S. Supraclavicular lymph node: incidence of unsuspected metastatic prostate cancer. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(September (9)):872–874. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagarkar R., Wagh A., Kokane G., Roy S., Vanjari S. Cervical lymph nodes: a hotbed for metastasis in malignancy. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019;71(October (S1)):976–980. doi: 10.1007/s12070-019-01664-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López F. Cervical lymph node metastases from remote primary tumor sites: Cervical Lymph Node Metastases from a Non-Head and Neck Primary. Head Neck. 2016;38(Avr. (S1)):E2374–E2385. doi: 10.1002/hed.24344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., for the SCARE Group The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z.-Y. Lymph node metastases in the neck from an unknown primary: report on 113 patients. Acta Radiol. Oncol. 1983;22(1):17–22. doi: 10.3109/02841868309134334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellison E., LaPuerta P., Martin S.E. Supraclavicular masses: results of a series of 309 cases biopsied by fine needle aspiration. Head Neck: J. Sci. Specialt. Head Neck. 1999;21(3):239–246. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199905)21:3<239::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abramson S., Berdon W., Stolar C., Ruzal-Shapiro C., Garvin J. Stage IVN neuroblastoma: MRI diagnosis of left supraclavicular “Virchow’s” nodal spread. Pediatr. Radiol. 1996;26(10):717–719. doi: 10.1007/BF01383387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismi O., Vayisoglu Y., Ozcan C., Gorur K., Unal M. Supraclavicular metastasis from infraclavicular organs: retrospective analysis of 18 patients. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2017;10(4) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cervin J.R., Silverman J.F., Loggie B.W., Geisinger K.R. Virchow’s node revisited. Analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 152 fine-needle aspiration biopsies of supraclavicular lymph nodes. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1995;119(8):727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasuti J.F., Mehrotra R., Gupta P.K. Diagnostic value of fine‐needle aspiration in supraclavicular lymphadenopathy: a study of 106 patients and review of literature. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2001;25(6):351–355. doi: 10.1002/dc.10002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta N., Rajwanshi A., Srinivasan R., Nijhawan R. Pathology of supraclavicular lymphadenopathy in Chandigarh, north India: an audit of 200 cases diagnosed by needle aspiration. Cytopathology. 2006;17(2):94–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitra S., Ray S., Mitra P.K. Fine needle aspiration cytology of supraclavicular lymph nodes: our experience over a three-year period. J. Cytol./Indian Acad. Cytol. 2011;28(3):108. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.83465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R., Naran S., Lallu S., Fauck R. The diagnostic value of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the assessment of palpable supraclavicular lymph nodes: a study of 218 cases. Cytopathology. 2003;14(4):201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2003.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baji S.N., Anand V., Sharma R., Deore K.S., Chokshi M. Analysis of FNAC of cervical lymph nodes: experience over a two years period. Int. J. Med. Sci. Public Health. 2014;3(5):607–609. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fatima S., Arshad S., Ahmed Z., Hasan S.H. Spectrum of cytological findings in patients with neck lymphadenopathy-experience in a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011;12(7):1873–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silas O., Ige O., Adoga A., Nimkur L., Ajetunmobi O. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) as a diagnostic tool in paediatric head and neck lymphodenopathy. J. Otol. Rhinol. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.4172/2324-8785.1000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welling R.E. Carcinoid tumor metastatic to neck. Arch. Surg. 1975;110(Janv. (1)):111. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1975.01360070111018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tha T., Saa M., Aha T. Primary retroperitoneal neuroendocrine tumor with nonspecific presentation: a case report. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020;15(Juill. (9)):1663–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández Aceñero M.J., Caso Viesca A., Díaz del Arco C. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the management of supraclavicular lymph node metastasis: review of our experience. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2019;47(mars (3)):181–186. doi: 10.1002/dc.24064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]