Abstract

Purpose:

Understand physician management of thyroid cancer-related worry.

Methods:

Endocrinologists, general surgeons, and otolaryngologists identified by Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) patients were surveyed 2018–2019 [response rate 69% (448/654)] and asked to rate in general their patients’ worry at diagnosis and action they take for worried patients. Multivariable weighted logistic regressions were conducted to determine physician characteristics associated with reporting thyroid cancer as “good cancer” and with encouraging patients to seek help managing worry outside the physician-patient relationship.

Results:

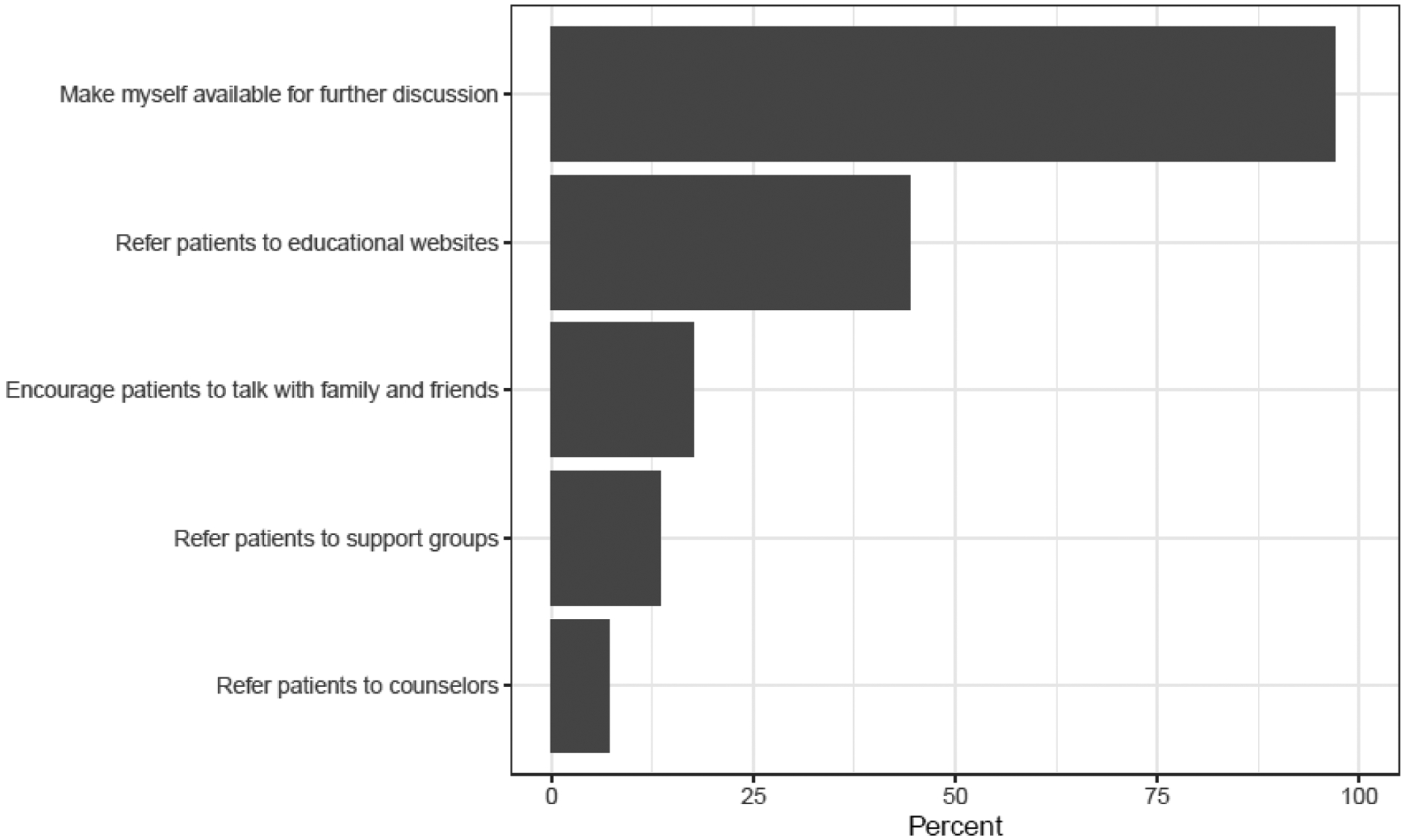

Physicians reported their patients as quite/very worried (65%), somewhat worried (27%) and a little/not worried (8%) at diagnosis.

Half the physicians tell patients thyroid cancer is a “good cancer”. Otolaryngology [odds ratio (OR) 1.87, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08–3.21, versus endocrinology], private practice (OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.32–4.68, versus academic setting) and Los Angeles (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.45–3.46, versus Georgia) were associated with using “good cancer”. If patients are worried, 97% of physicians make themselves available for discussion, 44% refer to educational websites, 18% encourage communication with family/friends, 13% refer to support groups and 7% to counselors. Physicians who perceived patients being quite/very worried were less likely to use “good cancer” (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.84) and more likely to encourage patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.17–2.82).

Conclusion / Implications for cancer survivors:

Physicians perceive patient worry as common and address it with various approaches, with some approaches of unclear benefit. Efforts are needed to develop tailored interventions targeting survivors’ psychosocial needs.

Keywords: thyroid cancer, worry, good cancer, population-based study, survey

BACKGROUND

Differentiated thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy affecting more than 50,000 patients in the United States annually [1]. For the vast majority of patients, it carries a favorable prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of >98% [1]. Despite its excellent prognosis, there is growing evidence highlighting the fact that overall cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors remains common, not only at time of diagnosis but even several years later [2–5]. We previously found that worry was prevalent among a diverse cohort of 2,215 thyroid cancer survivors with a favorable prognosis who were surveyed two to four years following diagnosis [2]. Specifically, 88% of patients reported that at time of diagnosis worrying about their thyroid cancer made them feel upset, 63% that it made it difficult to carry out their daily activities and 45% that it made them feel distant from family and friends [2]. Additionally, prior work suggests that thyroid cancer-related worry can impact cancer care [2, 6].

Although worry in thyroid cancer survivors is prevalent, information on strategies physicians use to manage this worry is lacking. Prior studies in other cancers with favorable prognosis have shown that effective physician-patient communication is critical to patient understanding of outcomes, such as recurrence risk, and can reduce anxiety [7, 8]. However, a qualitative study of thyroid cancer patients found that when physicians tell patients they have a “good cancer” it invalidates their fears of having cancer and creates mixed and confusing emotions [9]. Yet it is not known what proportion of physicians try to reassure patients with the description “good cancer”. In view of the importance of addressing the psychosocial needs of cancer patients in providing quality survivorship care [10], it is critical to understand what recommendations and actions physicians take to manage patient thyroid cancer-related worry, including strategies beyond physician-patient interactions.

We conducted a large prospective study of endocrinologists and surgeons who treat thyroid cancer patients from a population-based cohort and assessed physician management of cancer-related worry in thyroid cancer survivors. We hypothesized that although physicians perceive worry in thyroid cancer survivors to be common, actions taken to manage worry outside the physician-patient relationship remain underutilized.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Selected physicians were identified by a population-based cohort of thyroid cancer patients who previously reported on their cancer-related worry [2]. Specifically, patients diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries of Georgia and Los Angeles county were asked to report endocrinologists and surgeons involved in managing their thyroid cancer [2, 11–13]. Physicians identified by more than one patient were surveyed (n=482) and a random sample of those identified by just one patient were sent surveys (n=172). Using similar survey methodology to prior work, the survey was mailed to identified physicians with a cash incentive to enhance response rate [14]. Follow-up was conducted by phone, fax or email to non-responders. Double data entry method was used to ensure <1% error. Physicians completed surveys October 2018 to August 2019.

Of the 699 physicians identified, 45 were ineligible because they were deceased prior to the initial mailing, retired or were no longer with the practice on record and could not be located. A total of 654 physicians were response-eligible and 448 responded to the survey. Response rate was 69% (448/654) (calculated by dividing the number of respondents by the response-eligible physicians) and cooperation rate was 93% (448/483) (calculated by dividing the number of respondents by all physicians who were able to be contacted) [15].

The study was approved by the University of Michigan (HUM00113715), the University of Southern California (HS-16–00646), the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (California State Institutional Review Board), the Georgia Department of Public Health and the Emory University Institutional Review Boards (IRB00093983), and received approval from the California Cancer Registry. A waiver of written informed consent was obtained for all subjects in this study.

Survey Questionnaire Design and Content

The questionnaire content was developed based on prior literature, a conceptual framework and our team’s prior experience in surveying physicians caring for thyroid cancer patients [6, 16–19]. We used standard techniques to evaluate content validity including systematic review by clinicians and survey design experts and piloting in a select cohort of physicians prior to survey administration. Physicians were not asked to recall specific patients but were asked in general regarding their patients’ worry at time of diagnosis and what action they take if patients are worried.

Measures

Physician reported statements of reassurance

Surveyed physicians were asked their general views on topics related to patient worry: “If patients are worried, what do you typically tell them”? Answer options included: “I tell them details on prognosis, including information on death and recurrence”, “I tell them that thyroid cancer is a good cancer”, “I tell them that their doctors are experienced treating this cancer”. Physicians were asked to select all that apply and each was then categorized as yes/no.

Physician reported actions to manage patient worry

Surveyed physicians were asked to select all actions they take if their patients are worried. Options included making themselves available for further discussion, referring patients to educational websites, referring patients to support groups, referring patients to counselors, and encouraging patients to talk with family and friends.

Physician report on the role of patient worry on healthcare utilization and treatment intensity

Surveyed physicians were asked to rate whether they thought that patient worry about thyroid cancer progression or survival increases any of the following: number of patient visits, number of imaging studies, amount of lab work, number of referrals, length of clinic visits, likelihood of more intensive surgical management or medical management. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: never, rarely, sometimes, often, a lot. These were then categorized as never/rarely, sometimes, often/a lot.

Covariates

Covariates in the analyses included physician characteristics and physician perceived patient worry at time of thyroid cancer diagnosis. Physician characteristics included specialty (endocrinology, general surgery, otolaryngology, other), practice setting (academic medical center, large medical group of staff-model HMO, private practice, other), years in practice (<10, 10–19, 20–29, ≥30), thyroid cancer patient volume in past year (≤10, 11–30, 31–50, >50) and SEER site (Los Angeles county, Georgia). Physicians who reported being endocrine surgeons (n=16) or surgical oncologists (n=13) were categorized as general surgeons, as these are general surgery subspecialties. Based on additional information provided by the physician, we re-categorized physicians who answered “other” for physician specialty into one of the following physician specialties: endocrinology, general surgery, otolaryngology. We excluded physicians who could not be re-categorized in the above-mentioned specialties from the analyses (n=8).

Respondents were asked to rate in general how worried their thyroid cancer patients are at time of diagnosis. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale: not at all worried, a little worried, somewhat worried, quite worried, very worried. For the purpose of the analyses, physician perceived patient worry at time of diagnosis was categorized as not at all/a little/somewhat worried versus quite/very worried.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were generated and non-weighted frequencies were reported. All statistical analyses incorporated weights to assure that our statistical inference would be representative of the target population (physicians treating thyroid cancer patients) and to reduce potential non-response bias. The weights were computed for non-response using physician characteristics (specialty, SEER site and whether one versus two or more surveyed patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer identified physicians) to account for disproportionate non-response rates across different physician subgroups [20, 2].

Separate multivariable weighted logistic regression models were used to determine factors associated with report of thyroid cancer as “good cancer” to worried patients, report of telling patients their doctors are experienced in treating thyroid cancer, and with encouraging patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship. For the latter analysis, the outcome of encouraging patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship was obtained by combining the following options: referring patients to educational websites, referring patients to support groups, referring patients to counselors, encouraging patients to talk with family and friends, and categorized as yes/no. Due to small sample size of physicians not providing patients with details on prognosis, a multivariable analysis using this outcome measure was not conducted. Model covariates included physician specialty, practice setting, years in practice, thyroid cancer patient volume in the past year, SEER site and severity of physician perceived patient worry at time of diagnosis (dichotomous covariate: not at all/a little/somewhat worried versus quite/very worried).

Missing data were <5% per survey item. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15.1 and R version 3.6.1. We used Wald 95% CI to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Overall, 42% of physicians were endocrinologists, 30% general surgeons and 28% otolaryngologists. The majority of physicians were employed in private practice (55%); 31% cared for ≤10 thyroid cancer patients in the past year. A total of 51% of physicians were identified by patients from the Los Angeles and 49% from the Georgia SEER site. A total of 65% of physicians reported that in general their patients were quite/very worried, 27% that they were somewhat worried and 8% that they were a little/not at all worried at time of thyroid cancer diagnosis.

Physician reported statements of reassurance and actions to manage patient worry

Overall, 91% of physicians reported providing details on prognosis to worried patients, 60% tell them their physicians are experienced with thyroid cancer and 49% tell them thyroid cancer is a “good cancer”. A total of 408 physicians (91%) selected more than one option. Figure 1 shows that the overwhelming majority of physicians reported making themselves available for further discussion if patients are worried (97%). Other actions taken less frequently included referring patients to educational websites (44%), encouraging communication with family and friends (17%), referring patients to support groups (13%) and to counselors (7%). Overall, 55% of physicians reported they utilize at least one of the options outside the physician-patient relationship to manage patient worry.

Figure 1.

Physician reported actions to manage patient worry. Respondents were asked to select all actions they take if their patients are worried.

Table 1 displays factors associated with telling patients they have a “good cancer”, which included otolaryngology specialty (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.08–3.21, p=0.024, compared to endocrinology), private practice (OR 2.48, 95% CI 1.32–4.68, p=0.005, compared to academic setting) and Los Angeles county (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.45–3.46, p<0.001, compared to Georgia). Physicians who perceived their patients being quite or very worried at diagnosis were less likely to use the term “good cancer” (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.84, p=0.006).

Table 1.

Physician characteristics associated with reporting thyroid cancer as a “good cancer” to worried patients

| Characteristics | N (%)* | OR (95% CI) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician specialty | |||

| Endocrinology | 73 (40) | Ref | Ref |

| General surgery | 68 (51) | 1.33 (0.73–2.43) | 0.348 |

| Otolaryngology | 78 (60) | 1.87 (1.08–3.21) | 0.024 |

| Practice setting | |||

| Academic medical center | 27 (32) | Ref | Ref |

| Large medical group or staff-model HMO | 56 (48) | 1.52 (0.77–3.00) | 0.225 |

| Private practice | 137 (55) | 2.48 (1.32–4.68) | 0.005 |

| Years in practice | |||

| <10 | 38 (45) | Ref | |

| 10–19 | 69 (47) | 0.93 (0.52–1.66) | 0.796 |

| 20–29 | 64 (53) | 1.10 (0.58–2.08) | 0.768 |

| ≥30 | 48 (51) | 0.89 (0.44–1.78) | 0.735 |

| Thyroid cancer patient volume in past year | |||

| ≤10 | 76 (55) | Ref | Ref |

| 11–30 | 81 (52) | 0.85 (0.49–1.46) | 0.550 |

| 31–50 | 27 (43) | 0.78 (0.38–1.61) | 0.498 |

| >50 | 37 (40) | 0.81 (0.39–1.68) | 0.571 |

| Physician perceived patient worry at time of diagnosis | |||

| Not at all to somewhat worried | 94 (60) | Ref | Ref |

| Quite/Very worried | 129 (44) | 0.54 (0.35–0.84) | 0.006 |

| SEER Site | |||

| Georgia | 84 (41) | Ref | Ref |

| Los Angeles | 139 (57) | 2.24 (1.45–3.46) | <0.001 |

Percentages weighted for non-response.

Correlates of telling patients their doctors are experienced in treating thyroid cancer included otolaryngology specialty (OR 3.30, 95% CI 1.87–5.82, p<0.001, compared to endocrinology), more years in practice (e.g. 10–19 years: OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.11–3.54, p=0.021, compared to <10 years) and higher volume of thyroid cancer patients seen in the past year (>50 patients: OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.52–6.42, p=0.002, compared to ≤10). Additionally, physicians who perceived their patients being quite or very worried at diagnosis were more likely to tell them they are experienced in treating their cancer (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.08–2.54, p=0.022) (data not shown).

Table 2 demonstrates factors associated with encouraging patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship. Physicians who perceived their patients being quite or very worried at diagnosis were more likely to encourage patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.17–2.82, p=0.008).

Table 2.

Physician characteristics associated with encouraging patients to seek help outside the physician-patient relationship

| Characteristics | N (%)* | OR (95% CI) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician specialty | |||

| Endocrinology | 103 (59) | Ref | Ref |

| General surgery | 67 (50) | 1.19 (0.66–2.14) | 0.562 |

| Otolaryngology | 69 (54) | 1.08 (0.62–1.89) | 0.791 |

| Practice setting | |||

| Academic medical center | 55 (66) | Ref | Ref |

| Large medical group or staff-model HMO | 56 (49) | 0.52 (0.26–1.02) | 0.057 |

| Private practice | 128 (53) | 0.63 (0.35–1.16) | 0.136 |

| Years in practice | |||

| <10 | 55 (67) | Ref | Ref |

| 10–19 | 85 (60) | 0.77 (0.42–1.40) | 0.387 |

| 20–29 | 67 (57) | 0.90 (0.46–1.74) | 0.746 |

| ≥30 | 33 (35) | 0.30 (0.15–0.60) | 0.001 |

| Thyroid cancer patient volume in past year | |||

| ≤10 | 67 (48) | Ref | Ref |

| 11–30 | 72 (47) | 0.94 (0.55–1.61) | 0.819 |

| 31–50 | 42 (68) | 2.13 (1.01–4.51) | 0.048 |

| >50 | 60 (68) | 1.97 (0.97–3.99) | 0.060 |

| Physician perceived patient worry at time of diagnosis | |||

| Not at all to somewhat worried | 69 (45) | Ref | Ref |

| Quite/Very worried | 174 (61) | 1.82 (1.17–2.82) | 0.008 |

| SEER Site | |||

| Georgia | 115 (57) | Ref | Ref |

| Los Angeles | 129 (53) | 0.97 (0.62–1.49) | 0.874 |

Percentages weighted for non-response

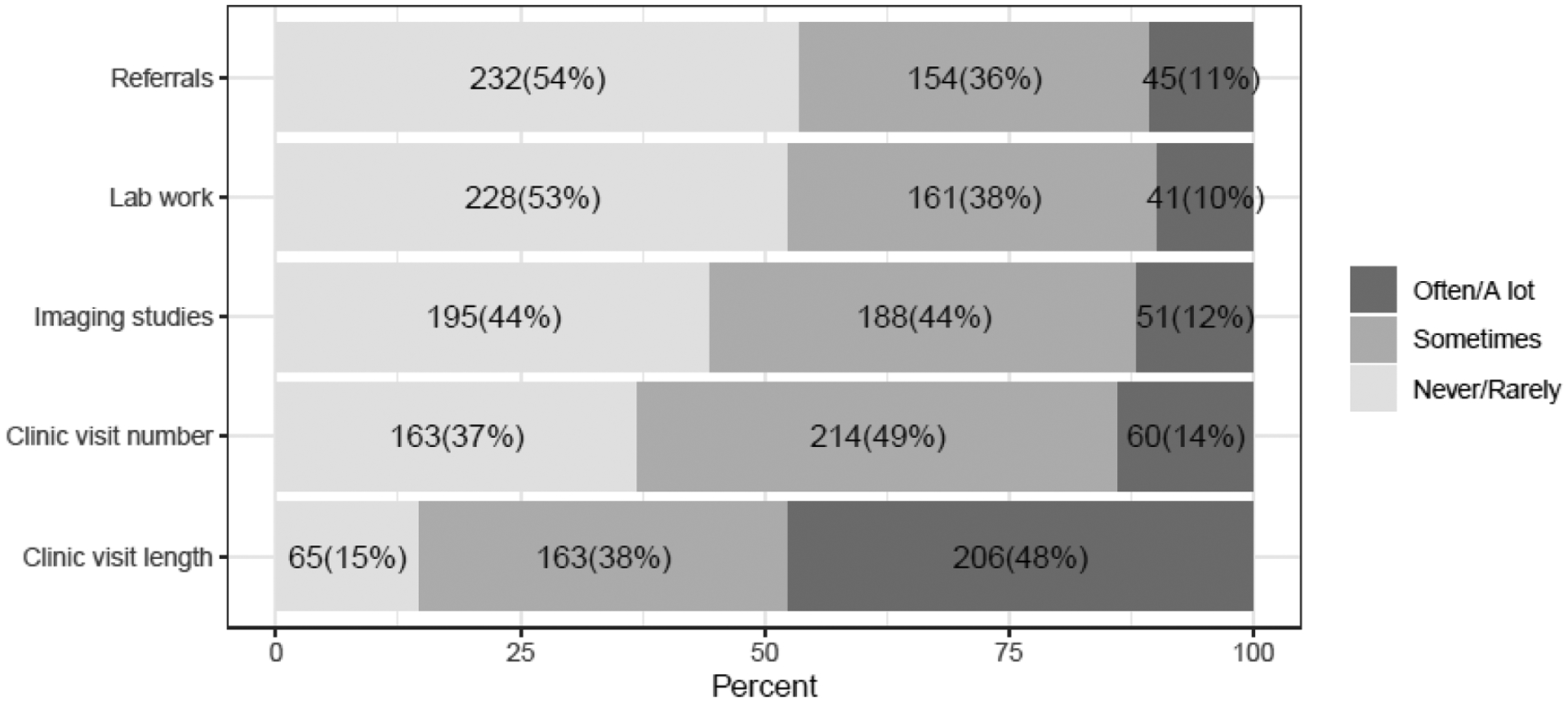

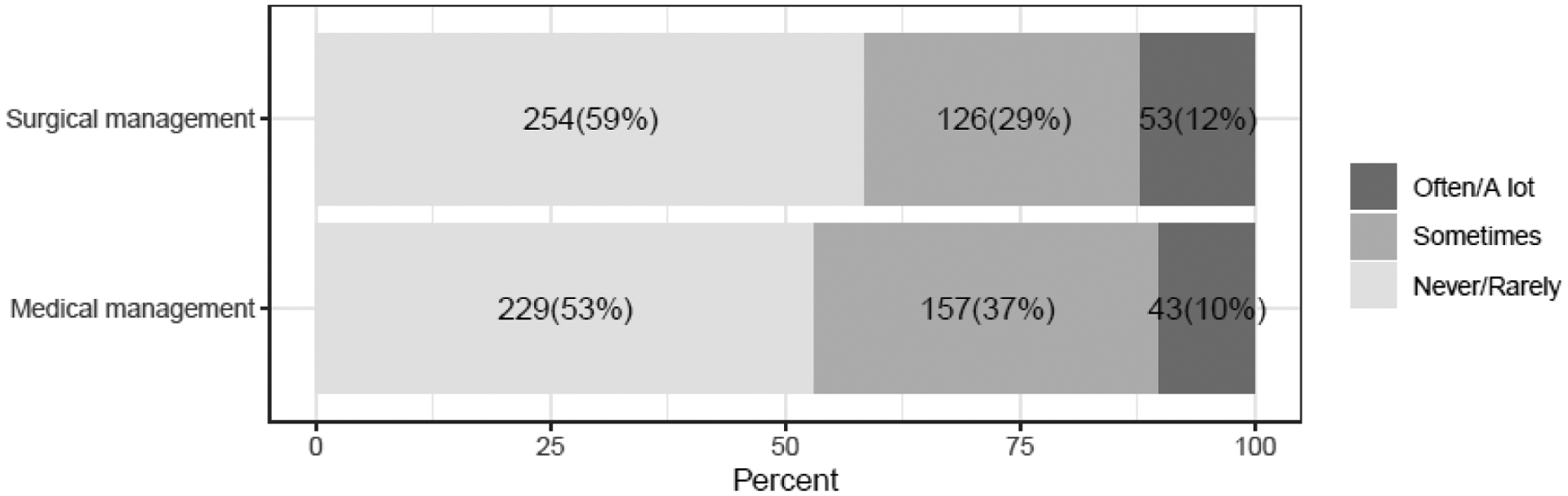

Physician report on the role of patient worry on healthcare utilization and treatment intensity

Figures 2a and 2b demonstrate the impact of physician perceived patient worry (categorized as never/rarely, somewhat, often/a lot) about thyroid cancer progression or survival as they relate to healthcare utilization and treatment intensity, respectively. Notably, 48% of physicians reported that patient worry about thyroid cancer progression or survival increases clinic visit length often/a lot.

Figure 2a.

Physician report on the role of patient worry in increasing aspects of healthcare utilization. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: never, rarely, sometimes, often, a lot.

Figure 2b.

Physician report on the role of patient worry in increasing treatment intensity. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale as follows: never, rarely, sometimes, often, a lot.

DISCUSSION

Complementary to a prior study on patient worry, this study of their treating physicians found that physicians perceive patient worry as common at time of diagnosis [2]. To help address patient worry, the overwhelming majority of physicians reported providing details on prognosis and reassuring on physician experience; however, one-half of the physicians stated they use the term “good cancer” to reassure their worried patients. Additionally, just over half reported utilizing options outside the physician-patient relationship to manage patient worry.

The tendency to describe thyroid cancer as a “good cancer” stems from its treatability and relatively favorable survival rates [9]. However, despite good intentions, as the treating physicians are likely trying to emphasize optimistic outcomes, no evidence currently exists to support the notion that telling patients they have a “good cancer” is helpful, and taking this approach may actually invalidate patients’ fears of having cancer and create mixed and confusing emotions [9]. Additionally, prior studies suggest that patient distress or worry is not necessarily related to the severity of their disease or prognosis [2, 21, 22]. Several factors may contribute to cancer-related worry, including specific personality traits, risk perception, symptom burden, unmet information needs and lack of social support systems [21, 23–27, 11].

We found that otolaryngologists were more likely than endocrinologists to report telling their worried thyroid cancer patients that they have a “good cancer”. Although an explanation for this finding is not known, it could be related to some of these physicians not trained in head and neck cancers or alternatively some caring for patients with more aggressive cancers than thyroid [28]. We also found that practice setting and regional differences may influence the approach physicians take to reassure worried patients. However, the lack of association between thyroid cancer patient volume and years in practice with likelihood of telling patients they have a “good cancer”, suggests that physician experience does not influence this practice.

The main approach used by physicians to manage patient worry in our study was allocating more time for discussion, which possibly led to the longer clinic visits reported. Even though prolonged verbal communication between physicians and patients has several advantages, such as capturing patients’ emotions and leading to improved understanding, there are no assurances that this approach appropriately alleviates patient worry. Despite good intentions, many physicians are not formally trained to make a valid and reliable assessment of cancer-related worry or any underlying superimposed mental health conditions, and thus may not adequately identify those in need of psychosocial support [29–32]. Prior studies have shown that there continues to be lack of clarity about the physicians’ responsibility to provide psychosocial care to cancer survivors with significant variation among different specialists regarding knowledge and confidence in delivering such care [33, 34]. In our study, just over half of the physicians utilized an approach to manage worry outside the physician-patient relationship, with fewer than 10% of physicians referring their worried patients to counselors. It has been shown in other cancer care settings that physicians often fail to recognize or treat unmet psychosocial needs of survivors and/or refer to appropriate caregivers [10, 29–32]. It is therefore essential to improve coordinated care to meet psychosocial health needs of thyroid cancer survivors.

Finally, our results suggest that physician perceptions about patient worry drive an increase in some aspects of health care utilization, such as clinic visit length, and treatment intensity. This is concordant with prior work in other cancers showing that cancer-related worry has been associated with more follow-up visits and telephone calls to healthcare providers [35, 36]. We have also previously shown that physicians place importance on patients’ worry about death when making decisions regarding radioactive iodine use in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer [6].

Our study has significant strengths. First, it complements a prior patient survey study, in which 88% reported that worry at diagnosis made them feel upset [2]. By surveying the physicians who provided care to these patients, we can broadly understand physician perception of patient worry. Recognizing how physicians perceive patient worry in general has implications understanding management. Second, we surveyed a large, diverse sample of physicians with adequate representation across specialties and outside the academic setting, had a high response rate and used detailed survey measures highly relevant to clinical practice.

Some study limitations merit comment. We relied upon physician report of general perceived patient worry, as we did not ask physicians to recall specific patients. Physician perception of thyroid cancer patients’ worry in general is pertinent given recent recognition of this issue [2–5], however, we recognize there is likely variation in the severity of individual patient worry. Also, even though our study targeted a population-based sample of physicians who treat thyroid cancer, it is limited to physicians identified by patients in the SEER Georgia and Los Angeles databases. However, the geographic areas included in SEER were selected for their epidemiologically significant population subgroups and are similar to the general United States population with regard to measures of poverty and education [37].

Our study has significant implications for both physicians and patients. Despite the vast majority of patients with thyroid cancer having an excellent prognosis, it is well known that cancer-related worry is common [1–5]. The majority of physicians perceive patient worry as common at thyroid cancer diagnosis. They recognize that this as an issue for their patients, and make efforts to address this worry with various approaches. However, how optimal such approaches are in ameliorating patient worry remains unclear for both patients (e.g., labeling thyroid cancer a “good cancer”) and physicians (e.g., time constraints with assuming a significant portion of responsibility), and may lead to increased healthcare utilization. Our findings highlight the urgent need to focus on worry in understudied cancers, including low-risk thyroid cancer, as well as the need to better understand which worry management strategies are optimal and effective for thyroid cancer patients. Additionally, there is a need for more physician education and skill building regarding recognition and management of the psychosocial aspects of care of thyroid cancer survivors. As the management of cancer-related worry may be an issue that is beyond the scope of a single physician, multidisciplinary efforts should be undertaken to improve coordinated and comprehensive care in order to support psychosocial health needs, reduce worry and psychosocial morbidity, and foster a better quality of life for thyroid cancer survivors. Finally, our study findings also highlight the need for the development of targeted, tailored, innovative interventions to address thyroid cancer patient worry and to improve patient care.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Brittany Gay who assisted with manuscript formatting and review.

Funding: This work is supported by R01 CA201198 (NCI) to Dr. Haymart. Dr. Haymart is also supported by R01 HS024512 (AHRQ) and Dr. Papaleontiou by K08 AG049684 (NIA). The collection of cancer incidence data in California was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP006344 and the NCI’s SEER Program under contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California. The collection of cancer incidence data in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201800003I, Task Order HHSN26100001 from NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875-04 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and endorsement by the State of California and State of Georgia Departments of Public Health, the NCI and CDC or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the University of Michigan (HUM00113715), the University of Southern California (HS-16–00646), the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (California State Institutional Review Board), the Georgia Department of Public Health and the Emory University Institutional Review Boards (IRB00093983), and received approval from the California Cancer Registry. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: A waiver of written informed consent was obtained for all subjects in this study.

Data and/or Code Availability: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Maria Papaleontiou, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, North Campus Research Complex, 2800 Plymouth Road, Bldg 16, Rm 453S, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Bradley Zebrack, School of Social Work, University of Michigan, 1080 S. University, Room 2778, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

David Reyes-Gastelum, Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Diabetes, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, North Campus Research Complex, 2800 Plymouth Rd. Bldg. 16, 400S-20, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Andrew J. Rosko, Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, 1904 Taubman Center, 1500 E Medical Center Dr. SPC 5312, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Sarah T. Hawley, Division of General Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, North Campus Research Complex, 2800 Plymouth Road, Bldg 16, Rm G034, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Ann S. Hamilton, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, 2001 N. Soto St., SSB318E, MC9239, Los Angeles, CA 90089-9239.

Kevin C. Ward, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, 1518 Clifton Rd., NE RM 764, GCR Building Mailstop;1518-002-7AA, Atlanta, GA 30322.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/thyro.html. Accessed November 30 2019.

- 2.Papaleontiou M, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay BL, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Hawley ST et al. Worry in Thyroid Cancer Survivors with a Favorable Prognosis. Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1080–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedman C, Djarv T, Strang P, Lundgren CI. Fear of Recurrence and View of Life Affect Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: A Prospective Swedish Population-Based Study. Thyroid. 2018;28:1609–17. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedman C, Strang P, Djarv T, Widberg I, Lundgren CI. Anxiety and Fear of Recurrence Despite a Good Prognosis: An Interview Study with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Patients. Thyroid. 2017;27(11):1417–23. doi: 10.1089/thy.2017.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresner L, Banach R, Rodin G, Thabane L, Ezzat S, Sawka AM. Cancer-related worry in Canadian thyroid cancer survivors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):977–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papaleontiou M, Banerjee M, Yang D, Sisson JC, Koenig RJ, Haymart MR. Factors that influence radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23(2):219–24. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janz NK, Li Y, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Jagsi R, Kurian AW, An LC et al. The impact of doctor-patient communication on patients’ perceptions of their risk of breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(3):525–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie Z, Wenger N, Stanton AL, Sepucha K, Kaplan C, Madlensky L et al. Risk estimation, anxiety, and breast cancer worry in women at risk for breast cancer: A single-arm trial of personalized risk communication. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2226–32. doi: 10.1002/pon.5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randle RW, Bushman NM, Orne J, Balentine CJ, Wendt E, Saucke M et al. Papillary Thyroid Cancer: The Good and Bad of the “Good Cancer”. Thyroid. 2017;27(7):902–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen DW, Reyes-Gastelum D, Wallner LP, Papaleontiou M, Hamilton AS, Ward KC et al. Disparities in Risk Perception of Thyroid Cancer Recurrence and Death. Cancer. 2019;126(7):1512–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evron JM, Reyes-Gastelum D, Banerjee M, Scherer LD, Wallner LP, Hamilton AS et al. Role of Patient Maximizing-Minimizing Preferences in Thyroid Cancer Surveillance. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(32):3042–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.01411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallner LP, Reyes-Gastelum D, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Hawley ST, Haymart MR. Patient-Perceived Lack of Choice in Receipt of Radioactive Iodine for Treatment of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2152–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, Wallner LP, Kurian AW, Hamilton AS et al. Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(18):3668–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Association for Public Opinion Research- Response Rates. https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx. Accessed October 29 2019.

- 16.Haymart MR, Muenz DG, Stewart AK, Griggs JJ, Banerjee M. Disease severity and radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):678–86. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, Stewart AK, Sisson JC, Koenig RJ et al. Variation in the management of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2001–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, Stewart AK, Koenig RJ, Griggs JJ. The role of clinicians in determining radioactive iodine use for low-risk thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(2):259–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, Stewart AK, Griggs JJ, Sisson JC et al. Referral patterns for patients with high-risk thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(4):638–43. doi: 10.4158/EP12288.OR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grovers RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey Methodology. vol 2nd Edition. New York, NY: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS et al. Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(9):1827–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwak M, Zebrack BJ, Meeske KA, Embry L, Aguilar C, Block R et al. Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: a 1-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2160–6. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.45.9222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips KM, McGinty HL, Gonzalez BD, Jim HS, Small BJ, Minton S et al. Factors associated with breast cancer worry 3 years after completion of adjuvant treatment. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):936–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husson O, Mols F, Oranje WA, Haak HR, Nieuwlaat WA, Netea-Maier RT et al. Unmet information needs and impact of cancer in (long-term) thyroid cancer survivors: results of the PROFILES registry. Psychooncology. 2014;23(8):946–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morley S, Goldfarb M. Support needs and survivorship concerns of thyroid cancer patients. Thyroid. 2015;25(6):649–56. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banach R, Bartes B, Farnell K, Rimmele H, Shey J, Singer S et al. Results of the Thyroid Cancer Alliance international patient/survivor survey: Psychosocial/informational support needs, treatment side effects and international differences in care. Hormones (Athens). 2013;12(3):428–38. doi: 10.1007/BF03401308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):761–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NIH National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Oral Cavity and Pharynx Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html. Accessed December 5 2019.

- 29.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kutner JS, Najita JS et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobsen PB, Shibata D, Siegel EM, Lee JH, Fulp WJ, Alemany C et al. Evaluating the quality of psychosocial care in outpatient medical oncology settings using performance indicators. Psychooncology. 2011;20(11):1221–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Theobald DE, Edgerton S. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(4):1594–600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merckaert I, Libert Y, Delvaux N, Marchal S, Boniver J, Etienne AM et al. Factors that influence physicians’ detection of distress in patients with cancer: can a communication skills training program improve physicians’ detection? Cancer. 2005;104(2):411–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Leach CR, Ganz PA, Stefanek ME, Rowland JH. Who provides psychosocial follow-up care for post-treatment cancer survivors? A survey of medical oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2897–905. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janz NK, Leinberger RL, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Hawley ST, Griffith K, Jagsi R. Provider perspectives on presenting risk information and managing worry about recurrence among breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24(5):592–600. doi: 10.1002/pon.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cannon AJ, Darrington DL, Reed EC, Loberiza FR, Jr. Spirituality, patients’ worry, and follow-up health-care utilization among cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(4):141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebel S, Tomei C, Feldstain A, Beattie S, McCallum M. Does fear of cancer recurrence predict cancer survivors’ health care use? Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):901–6. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER): Population Characteristics. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/characteristics.html. Accessed December 10 2019.