Abstract

The objective of this study is to analyze the morbidity of selective neck dissection (SND) in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC). This is a cross-sectional study of 106 consecutive patients with T1 and T2 (AJCC seventh edition) stage cancers. Morbidity in terms of scar characteristics, cervical lymphedema, sensation, shoulder dysfunction, and smile asymmetry were analyzed. Scar outcomes were inferior in terms of poor complexion in 15 patients (14.2%), poor texture in 25 patients (23.6%), limited skin movement in 9 patients (8.5%), soft tissue deficit in 13 patients (12.3%), and lymphedema in 14 patients (13.2%). Smile asymmetry was seen in 29.2%. Shoulder dysfunction was seen in 7.5%. Patients who received adjuvant treatment had significant scar issues (p = 0.001), lymphedema (p < 0.001), and sensory issues (p = 0.003). SND in OCSCC is not without morbidity. Smile asymmetry was the commonest problem. Patients who got adjuvant treatment had significantly more morbidity.

Keywords: Selective neck dissection, Oral cancer, Morbidity, Sentinel node biopsy, Shoulder dysfunction

Introduction

Oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) has a high propensity to spread to the neck. Occult metastasis to cervical lymph nodes in OCSCC ranges from 30 to 40% [1]. Surgery is the usually the preferred modality of treatment and the adjuvant therapy in the form of radiotherapy (RT) or chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is reserved for adverse pathological features or high-stage disease [2]. Surgery involves a wide resection of the primary lesion and neck dissection. Neck dissection is usually an elective selective neck dissection in a clinically negative neck, where only the primary echelon nodes [3] are addressed or a therapeutic neck dissection in a clinically positive neck. Though a comprehensive neck dissection is preferred in a node-positive neck, there are also reports favoring a selective neck dissection in such patients [4, 5]. Most of the previous studies have concluded that selective neck dissection (SND) is a safe and less morbid procedure [6, 7]. The comparison in many of these studies are with other more invasive procedures such as modified radical neck dissection or radical neck dissection. SND is a less morbid procedure [8]. But, it is not without morbidity. This is important in the background of studies on sentinel node biopsy (SNB) and remote access approaches [9]. The hypothesis of the present study was that SND has its own morbidity profile. The purpose of this study was to analyze the morbidity of SND done in patients with OCSCC in terms of scar characteristics, lymphedema, sensory disturbances, shoulder dysfunction, and facial smile asymmetry.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study conducted in a university hospital. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. The study included early-stage clinically T1 or T2 (AJCC seventh edition) OCSCC patients with or without clinical or radiological nodes (N0 and N+). Included node-positive patients had only nodes in upper neck levels (I and II). All the patients were treated with wide excision of the primary tumor and selective neck dissection including levels I to IV. Level II b nodes were dissected in all patients. Majority of the patients had tongue as the primary tumor; hence, level IV was also included. The procedure was done using a lateral mid-neck transverse neck crease incision. Adjuvant treatment either RT or CRT was decided based on the pathological risk factors. The patients were followed up monthly in the first year, once in 2 months in the second year, once in 3 months in the third year, and once in 6 months thereafter. Patients who have completed at least 6 months of treatment, with no locoregional or distant recurrence or a second primary were included in the study. The mean duration from completion of treatment was 14 months (6–30 months). Patients with advanced T stages (T3 and T4) and N stages (lower neck nodes, contralateral neck nodes, and N3 nodes) were excluded. Patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma and with previous head and neck cancer treatment were also excluded. During the clinical interview, the demographic parameters were recorded and the disease and treatment parameters were retrieved from the electronic medical records. Morbidity in terms of scar characteristics (complexion, texture, skin movement, soft tissue deficiency), cervical lymphedema, sensation, shoulder dysfunction, and facial smile asymmetry was analyzed. Scar characteristics were scored subjectively from 0 to 3/0 to 2 by the examining clinician (Table 1) [10]. MD Anderson lymphedema scoring was used to assess neck lymphedema (Table 2) [11]. Sensations from preauricular, sternocleidomastoid (SCM), infraclavicular, and supraclavicular areas were assessed per the neurologic standard classification of the American Spinal Injury Association. Tactile sensation (epicritic sensitivity) was assessed by light touch with a fine brush, and protopathic (pain) sensitivity was assessed by pin prick. Sensitivity was categorized by means of a three-tiered scale (0, absent; 1, impaired; 2, normal); thus, higher scores indicate less impairment [12]. Shoulder dysfunction was assessed with the Constant shoulder score (CSS), a validated test that combines patient symptom scores (35% of score sum) and objective scores of active shoulder function (65% of score sum) [13]. The CSS has been previously used and proven its utility in assessment of shoulder function after neck dissection. This scoring system consists of four variables that are used to assess the function of the shoulder. The right and left shoulders are assessed separately. The subjective variables are pain and activities of daily living (sleep, work, recreation/sport) which give a total of 35 points. The objective variables are range of motion and strength which give a total of 65 points. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better shoulder function [14]. Facial smile asymmetry due to the angle of mouth deviation was assessed by asking the patient to smile or show the teeth and was subjectively scored by the clinician as 5 if the asymmetry is noted only at initiation of smile and 10 if there is asymmetry even at rest [15]. A univariate analysis was done to see the correlation of adjuvant therapy and free flap reconstruction with neck morbidity. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 20. The Kruskal–Wallis test and chi-square test were used to test statistical significance.

Table 1.

Assessment and scoring of cervical scar parameters and soft tissue characteristics [8]

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Complexion (0–3) | White scar—no change of complexion | Slight hyperemia in some places | Complete hyperemia of the scar, pink colored | Broadened reddish scar with telangiectasia |

| Texture (0–3) | Scar, not visible at first glance, within skin tension lines | Scar apparently beyond skin tension lines | Slight depression, up to 1 mm below skin surface, hypertrophy in some places | Constricting scar edge formation, nodes or defects, pronounced hypertrophy |

| Skin movement (0–2) | Completely adherent to subcutaneous tissue, no mobility, platysma function absent | Scars adherent in some places, impaired platysma function | Scar and surrounding skin are mobile, normal platysma function | |

| Soft tissue swelling (0–2) | Increased skin tension, constricted movement | Moderate swelling, mobility normal | No signs of swelling | |

| Soft tissue deficit (0–2) | Neck structures can be traced through skin | Soft tissue deficit, but without outlining underlying neck structures | No asymmetry, normal surface pattern | |

Table 2.

MD Anderson modified Foldi’s lymphedema scale [9]

| Stages | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No visible edema but patient reports heaviness |

| 1a | Soft visible edema, no pitting, reversible |

| 1b | Soft pitting edema, reversible |

| 2 | Firm pitting edema, not reversible, no tissue changes |

| 3 | Irreversible, tissue changes |

Results

The study cohort included 106 patients. The mean age was 55 years (range of 18–81 years) and the median follow-up time after completion of treatment was 21 months (range 6–127 months). The number of male patients were 74 (69.8% and females were 32 (30.2%). All these patients either had T1 (66.1%) or T2 (33.9%) disease clinically according to the AJCC seventh edition classification. Ninety-eight patients (92%) had oral tongue primaries. Ninety-three patients (87%) were clinical and radiological node negative. Eighty patients (75.5%) received no further adjuvant treatment. Forty-four (41.5%) patients had their defects reconstructed with free flaps. The policy followed was to reconstruct the tongue if the defect is more than two thirds of the total volume on rough estimation of the defect after resection. Table 3 shows the demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics. Figure 1 shows a neck dissection scar with good outcome.

Table 3.

Demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics

| Patient characteristics (n = 106) | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 74 (69.8) |

| Female | 32 (30.2) | |

| Subsite | Tongue | 98 (92.5) |

| Buccal mucosa | 5 (4.7) | |

| Upper alveolus | 3 (1.9) | |

| Clinical T stage | T1 | 70 (66.1) |

| T2 | 36 (33.9) | |

| Clinical N stage | N0 | 93 (87.7) |

| N1 | 9 (8.6) | |

| N2b | 4 (3.7) | |

| Pathological T | T1 | 72 (67.9) |

| T2 | 30 (28.3) | |

| T3 | 1 (0.9) | |

| T4 | 3 (2.8) | |

| Pathological N | N0 | 83 (78.3) |

| N1 | 14 (13.2) | |

| N2b | 9 (8.5) | |

| Adjuvant | None | 80 (75.5) |

| RT | 15 (14.2) | |

| CTRT | 11 (10.3) | |

| Free flap surgery | Done | 44 (41.5) |

| Not done | 62 (58.5) | |

Fig. 1.

A selective neck dissection scar with good outcome scores

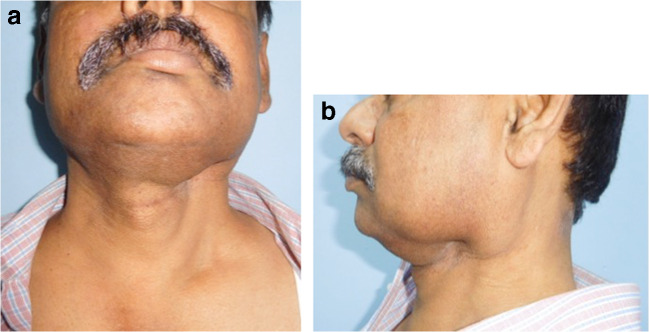

Scar outcomes were inferior in terms of poor complexion in 15 patients (14.2%), poor texture (Fig. 2a, b) in 25 patients (23.6%), limited skin movement over the scar in 9 patients (8.5%), evident soft tissue deficit (Fig. 3a, b) in 13 patients (12.3%), and lymphedema (Fig. 4a, b) in 14 patients (13.2%). Cutaneous sensation was absent in 2, 9, and 6 patients in the preauricular, SCM, and supraclavicular areas respectively. Marginal mandibular nerve paresis/palsy (Fig. 5) was seen in 29.2% of patients. The Constant shoulder score was poor in 8 (7.5%) patients. Table 4 shows the details of the neck morbidity. Patients who received adjuvant (RT/CTRT) had significant scar issues (p = 0.001), lymphedema (p < 0.001), and sensory issues (p = 0.003). But the difference in shoulder dysfunction and facial smile asymmetry was not significant in these patients. Patients with flap reconstruction had significantly more lymphedema (p = 0.019) (Table 5). None of the patients in this study had hypoglossal nerve injury, phrenic nerve injury, or thoracic duct injury.

Fig. 2.

a Hypertrophic scar, frontal view. b lateral view

Fig. 3.

a Soft tissue deficit, post left selective neck dissection, frontal view. b lateral view

Fig. 4.

a Lymphedema, post neck dissection, frontal view. b lateral view

Fig. 5.

Right marginal mandibular nerve weakness, after selective neck dissection

Table 4.

Morbidity

| Morbidity outcome parameters (n = 106) | Frequency n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Scar outcomes | Poor complexion | 15 (14.2) |

| Poor texture | 25 (23.6) | |

| Limited skin movement | 9 (8.5) | |

| Evident soft tissue deficit | 13 (12.3) | |

| Lymphedema | 14 (13.2) | |

| Poor sensation | Preauricular area | 2 (1.9) |

| SCM area | 9 (8.6) | |

| Supra clavicular area | 6 (5.8) | |

| Facial smile asymmetry | 31 (29.2) | |

| Poor Constant shoulder score (CSS) (shoulder dysfunction) | 8 (7.5) | |

Table 5.

Correlation of morbidity with adjuvant treatment and free flap reconstruction

| Morbidity | Adjuvant n (%) | p value | Free flap, n (%) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes 26 (25) | No 80 (75) | Yes 44 (42) | No 62 (58) | |||

| Any scar issues | 20 (77) | 5 (6) | 0.001 | 12 (27) | 13 (21) | 0.5 |

| Lymphedema | 14 (54) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 | 10 (23) | 4 (6) | 0.019 |

| Sensory morbidity | 9 (35) | 1 (1) | 0.003 | 6 (14) | 4 (6) | 0.43 |

| Facial smile asymmetry | 8 (31) | 23 (29) | 0.53 | 10 (23) | 21 (34) | 0.22 |

| Shoulder dysfunction | 3 (11) | 5 (6) | 0.22 | 4 (9) | 4 (6) | 0.5 |

Discussion

There are earlier reports that have studied the morbidity of neck dissection. Functional and esthetic complications in relation to shoulder dysfunction, marginal mandibular nerve paresis, scar, lymphedema, and cutaneous hypoesthesia/anesthesia have been shown to be present in patients who undergo this surgery. But the incidence and significance of this morbidity have been reported either way in literature. Shoulder dysfunction is reported in 7 to 20% at 6 months, lymphedema from 19 to 26%, marginal mandibular nerve problems in 10 to 30%, and scar-related problems on 10 to 40% of patients [6, 7, 16–19]. Most of these studies have concluded that SND is a safe and less morbid procedure. The comparison in many of these studies are with other more invasive procedures such as modified radical neck dissection or radical neck dissection. The hypothesis of the present study was that SND has its own morbidity profile. The aim of this study was to analyze the morbidity of SND done in patients with early-stage OCSCC in terms of scar characteristics, lymphedema, sensory disturbances, shoulder dysfunction, and facial smile asymmetry. A comparison with lesser morbid procedures was not part of the study.

The most common morbidity after SND is cutaneous sensory problems. The impact of these symptoms on the quality of life (QOL) have not been much looked into. Roh et al. reported that cervical nerve root-preserved patients showed a low incidence and severity of neck and shoulder pain compared with the nerve-removed subjects (p < 0.05). Loss of sensation was more frequently experienced in the nerve-removed group on the earlobe and the lateral neck of the operated side (p < 0.05). Depression and QOL scores were higher in the nerve-removed group and significantly correlated with pain intensity [20]. In the present study, cutaneous sensation was absent in 2, 9, and 6 patients in the preauricular, SCM, and supraclavicular areas respectively.

Teymoortash et al. [21] reported 19.2% lymphedema in the head and neck region after SND. Those patients with persistent lymphedema received lymphatic drainage therapy, which led to an improvement of the edema. Among them, the proportion of patients with previous radiotherapy treatment was 50%. In the same study, 34 (65.4%) out of the 52 patients developed sensory disturbances around the operation scar in the form of minor hypoesthesia. In our study, the number of patients with lymphedema were 14 (13.2%), where all of them have received adjuvant in the form of radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

The overall rate of marginal mandibular nerve neuropraxia in a heterogeneous group of patients undergoing neck dissection has been described at 16% [17]. Injury to the nerve will cause weakness of depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris leading to asymmetry of the lower lip particularly when smiling. There is some contribution to lower lip depression provided by the platysma muscle which is supplied by the cervical branches of the facial nerve and these nerves are invariably divided during neck dissection. Batstone et al. [22] in their cohort of patients reported an objective injury rate of 18% when analyzed objectively (15 of 85) and 23% when analyzed by patient (15 of 66). Unilateral neck dissections had an injury rate of 28% (13 of 47) and bilateral neck dissections had an injury rate of 11% (2 of 19). This is the only study identified in the literature, which addresses the rate of injury in patients undergoing level I neck dissection. In our study, facial smile asymmetry was seen in 29.2% of patients, which is comparable with other reports in the literature.

The Constant shoulder score was poor in 8 (7.5%) patients, although the immediate postoperative shoulder dysfunction in terms of symptoms were 43.4%. Similar findings have been reported by many authors. Watkins et al. [23] evaluated shoulder function in 34 patients undergoing selective neck dissection using a modified Constant’s score. Their results showed a negative effect on shoulder function after selective neck dissection, despite saving cranial nerve XI when compared with the non-operated side. The extent of shoulder impairment and activity limitations reported in the literature after any type of neck dissection is highly variable. Some of the variability and difficulties in comparing studies is related to the lack of a recognized, uniformly accepted instrument to measure shoulder-related outcomes.

The importance of the morbidity in selective neck dissections comes in the wake of presumably less morbid procedures like sentinel node biopsy and remote access neck dissections. Schilling et al. [24] in their 3-year report of the SENT trial reported minimal morbidity for SNB. Minor complications were seroma [1], hematoma [8], local infection [3], and lymphedema [1]. There were two notable complications: one phrenic nerve palsy and one patient had a cerebellar stroke secondary to surgery. Schiefke et al. [8] in their retrospective study in 24 patients with SNB and 25 patients with SND reported statistically significant difference in morbidity outcomes like scar characteristics, soft tissue deficit, and shoulder dysfunction and decreased incidence of lymphedema and marginal mandibular nerve paresis in the SNB group. Hernando et al. [25] in their comparative study between SNB group and elective neck dissection group; END (I–III), reported statistically significant differences between the groups in shoulder function and average scar length. However, differences in degree of lymphedema were not statistically significant. Neck hematomas and oro-cervical communications occurred only in the END group. From this study, it can be concluded that SNB presents less postoperative morbidity than END. Recently, robot-assisted and endoscope-assisted neck dissection (RAND) has begun to be used as an alternative method of neck dissection, one of the classic surgical procedures in head and neck surgery. Currently, there are four kinds of approaches for RAND: (1) modified facelift or retroauricular incision, (2) combined transaxillary and retroauricular incision, (3) transaxillary incision, and (4) transoral incision. RAND may help perform minimal access surgery and achieve excellent cosmetic results as well as the desired oncologic outcomes, but requires selecting an appropriate approach based on the different needs of neck dissections. Although experienced surgeons wishing to avoid large cervical incisions in patients can safely perform RAND, there are still quite a few limitations; surgical morbidity and oncologic outcomes should be verified by further prospective clinical trials with longer follow-up periods [26].

This study had its limitations. There was no control group to compare the morbidity with reportedly less morbid procedures. But, the sentinel node biopsy or remote access procedures are still not the standards of care and need further evaluation. This study will form the background for future studies to compare the outcomes of such less morbid procedures. Also, the morbidity assessment was conducted at variable time intervals of follow-up, though all the patients had a minimum period of follow-up of 6 months after completion of their treatment. The morbidity factors like lymphedema, scar characteristics, and marginal mandibular weakness are known to improve over time. The methodology used for facial asymmetry assessment was subjective.

Conclusion

SND in OCSCC is not without morbidity. Facial smile asymmetry due to loss of tone of angle of mouth muscles secondary to injury to marginal mandibular and cervical branch of facial nerve was the most common morbidity encountered by the clinician. Patients receiving adjuvant treatment had significantly more morbidity related to the scar, lymphedema, and sensation. This data may be a background to compare less morbid, but oncologically safe neck staging procedures in the future.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shah JP. Patterns of cervical lymph node metastasis from squamous carcinomas of the upper aerodigestive tract. Am J Surg. 1990;160:405–409. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80554-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernier J, Cooper JS. Chemoradiation after surgery for high-risk head and neck cancer patients: how strong is the evidence? Oncologist. 2005;10:215–224. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-3-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Cruz AK, Vaish R, Kapre N, Dandekar M, Gupta S, Hawaldar R, Agarwal JP, Pantvaidya G, Chaukar D, Deshmukh A, Kane S, Arya S, Ghosh-Laskar S, Chaturvedi P, Pai P, Nair S, Nair D, Badwe R, Head and Neck Disease Management Group Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in node negative oral cancers. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:521–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel RS, Clark JR, Gao K, O'Brien CJ. Effectiveness of selective neck dissection in the treatment of clinically positive neck. Head Neck. 2008;30:1231–1236. doi: 10.1002/hed.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Battoo AJ, Hedne N, Ahmad SZ, Thankappan K, Iyer S, Kuriakose MA. Selective neck dissection is effective in N1/N2 nodal stage oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.06.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng PT, Hao SP, Lin YH, Yeh AR. Objective comparison of shoulder dysfunction after three neck dissection techniques. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:761–766. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagedar NA, Gilbert RW. Selective neck dissection: a review of the evidence. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferlito A, Gavilán J, Buckley JG, Shaha AR, Miodonski AJ, Rinaldo A. Functional neck dissection: fact and fiction. Head Neck. 2001;23:804–808. doi: 10.1002/hed.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross GL, Soutar DS, Gordon MacDonald D, Shoaib T, Camilleri I, Roberton AG, Sorensen JA, Thomsen J, Grupe P, Alvarez J, Barbier L, Santamaria J, Poli T, Massarelli O, Sesenna E, Kovács AF, Grünwald F, Barzan L, Sulfaro S, Alberti F. Sentinel node biopsy in head and neck cancer: preliminary results of a multicenter trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:690–696. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiefke F, Akdemir M, Weber A, Akdemir D, Singer S, Frerich B. Function, post-operative morbidity, and quality of life after cervical sentinel node biopsy and after selective neck dissection. Head Neck. 2009;31:503–512. doi: 10.1002/hed.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith BG, Lewin JS. Lymphedema management in head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18:153–158. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283393799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maynard FM, Jr, Bracken MB, Creasey G, D JF, Jr, Donovan WH, Ducker TB, Garber SL, Marino RJ, Stover SL, Tator CH, Waters RL, Wilberger JE, Young W. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;214:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chepeha DB, Taylor RJ, Chepeha JC, Teknos TN, Bradford CR, Sharma PK, Terrell JE, Wolf GT. Functional assessment using Constant’s Shoulder Scale after modified radical and selective neck dissection. Head Neck. 2002;24:432–436. doi: 10.1002/hed.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May M. Facial paralysis, peripheral type: a proposed method of reporting. (Emphasis on diagnosis and prognosis, as well as electrical and chorda tympani nerve testing.) Laryngoscope. 1970;80:331–390. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prim MP, De Diego JI, Verdaguer JM, Sastre N, Rabanal I. Neurological complications following functional neck dissection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:473–476. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-1028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nason RW, Binahmed A, Torchia MG, Thliversis J. Clinical observations of the anatomy and function of the marginal mandibular nerve. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:712–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koybasioglu A, Tokcaer AB, Uslu S, Ileri F, Beder L, Ozbilen S. Accessory nerve function after modified radical and lateral neck dissections. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:73–77. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappiello J, Piazza C, Giudice M, De Maria G, Nicolai P. Shoulder disability after different selective neck dissections (level II-IV versus levels II-V): a comparative study. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:259–263. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000154729.31281.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roh JL, Yoon YH, Kim SY, Park CI. Cervical sensory preservation during neck dissection. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teymoortash A, Hoch S, Eivazi B, Werner JA. Postoperative morbidity after different types of selective neck dissection. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:924–929. doi: 10.1002/lary.20894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batstone MD, Scott B, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Marginal mandibular nerve injury during neck dissection. Head Neck. 2009;31:673–678. doi: 10.1002/hed.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watkins JP, Williams GB, Mascioli AA, Wan JY, Samant S. Shoulder function in patients undergoing selective neck dissection with or without radiation and chemotherapy. Head Neck. 2011;33:615–619. doi: 10.1002/hed.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schilling C, Stoeckli SJ, Haerle SK. Sentinel European Node Trial (SENT): 3-year results of sentinel node biopsy in oral cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2777–2784. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernando J, Villarreal P, Alvarez-Marcos F, Gallego L, García-Consuegra L, Junquera L. Comparison of related complications: sentinel node biopsy versus elective neck dissection. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:1307–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou S, Zhang C, Li D. Approaches of robot-assisted neck dissection for head and neck cancer: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]