Introduction

Friedreich Ataxia (FRDA) is a progressive neurological and systemic disorder that affects about one in 50,000 people worldwide (Strawser et al., 2017). It is caused by mutations, usually GAA repeat expansions (96%) but also point mutations or deletions (4%), in the FXN gene, resulting in decreased production of functional frataxin protein (Babady et al., 2007; Delatycki and Bidichandani, 2019). GAA length on the shorter allele inversely correlates with disease severity (Strawser et al., 2017). Frataxin is a small mitochondrial protein that functions in iron-sulfur-cluster biosynthesis (Colin et al., 2013). Its deficiency leads to difficulties in production of cellular ATP as well as sensitivity to reactive oxygen species in vitro (Rötig et al., 1997; Lodi et al., 2001; Pastore and Puccio, 2013; DeBrosse et al., 2016). These properties lead to neurological injury and clinical impairment, including ataxia, dysarthria, sensory loss, and weakness in FRDA patients. While most literature has focused on neurodegeneration in FRDA, the disorder also has a large developmental component (Koeppen et al., 2017a,b). In addition, individuals with FRDA develop cardiomyopathy, scoliosis and sometimes diabetes mellitus. The cardiomyopathy of FRDA is characterized by early hypertrophy, with later progression to fibrosis and systolic dysfunction, leading to death from end-stage heart failure (Tsou et al., 2011; Lynch et al., 2012; Strawser et al., 2017). Many agents are in development for FRDA, including some designed to ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction and others that seek to increase levels of functional frataxin (Strawser et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2018, 2021; Piguet et al., 2018; Zesiewicz et al., 2018a,b; Belbella et al., 2019; Rodríguez-Pascau et al., 2021).

NfL as a Biomarker of FRDA and Other Diseases

In many neurodegenerative diseases, the need for disease-modifying treatments is facilitated by identification of biomarkers to track disease progression. Such markers can capture subclinical changes in a rapid manner and show evidence of target engagement in clinical trials in slowly progressive neurological disorders. In other neurological disorders, including Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer's disease (AD), and Parkinson's disease (PD), neurofilament light chain levels (NfL) in body fluids such as serum, plasma or CSF may provide a biomarker for tracking disease activity including progression (Bridel et al., 2019; Forgrave et al., 2019; Aktas et al., 2020; Del Prete et al., 2020; Milo et al., 2020; Thebault et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Neurofilaments are cytoskeletal proteins located in both the peripheral and central nervous system, particularly in larger myelinated axons. They play a significant role in axonal growth and the determination of axonal caliber (Hsieh et al., 1994; Kurochkina et al., 2018; Bott and Winckler, 2020). Logically, as axons are damaged and die in neurodegenerative processes, NfL should leak into the interstitial space, then into CSF and plasma. Thus, concentrations of NfL should generally increase as neurodegenerative diseases progress and should reflect disease activity. For example, in progressive MS, NfL appears to track with neuronal and axonal death, the stage of disease, and treatment response. NfL concentration in the CSF of MS patients parallels T2 lesion changes on MRI. Similarly, plasma NfL concentration is higher in AD patients than in controls and is associated with greater cognitive deficit. Such findings suggest that NfL is a promising biomarker for determining the stage of disease, tracking progression and aiding in identification of disease-modifying treatments in neurological disorders. However, in stable MS, NfL levels may not track with clinical dysfunction, providing a reminder that changes in biomarkers must be interpreted in the context of clinical changes (Aktas et al., 2020).

In FRDA, data on NfL levels in serum is more complex. Most features of FRDA depend on genetic severity (GAA repeat length) and worsen over the course of time, thus correlating positively with disease duration or age (Strawser et al., 2017). Overall, the two main determinants of clinical severity in FRDA are genetic severity and disease duration. In the three studies evaluating serum NfL in FRDA patients, serum NfL is elevated in patients with FRDA when compared to controls and carriers (Zeitlberger et al., 2018; Clay et al., 2020; Hayer et al., 2020). This shows that serum NfL levels reflect a pathological process in FRDA. However, in these three studies NfL levels generally do not correlate with markers of clinical or genetic severity. Moreover, while NfL levels correlate positively with age in non-FRDA patients (controls and carriers) in cross sectional analysis, in FRDA patients, NfL levels are highest in young children and decrease with age as the disease progresses (Clay et al., 2020). Thus, serum NfL is paradoxically high in young individuals and far lower in older individuals with more severe disease. At later ages it even overlaps with control values. A greater genetic severity in early onset individuals could explain some of this paradox; however, NfL levels overall do not correlate with GAA repeat length after accounting for age, and they even appear to correlate inversely with GAA length in some of these studies. Accounting for age, individuals who are more severe genetically have lower levels of NfL. Interestingly, Nfl levels are relatively stable over 1–2 years; consequently, NfL levels could be used as an assessment of therapeutic response over the time used in most clinical trials. Still, while NfL may provide a biomarker of FRDA in some manner, the relationship of NfL to disease progression is complex suggesting its utility may be limited to certain situations.

Discussion

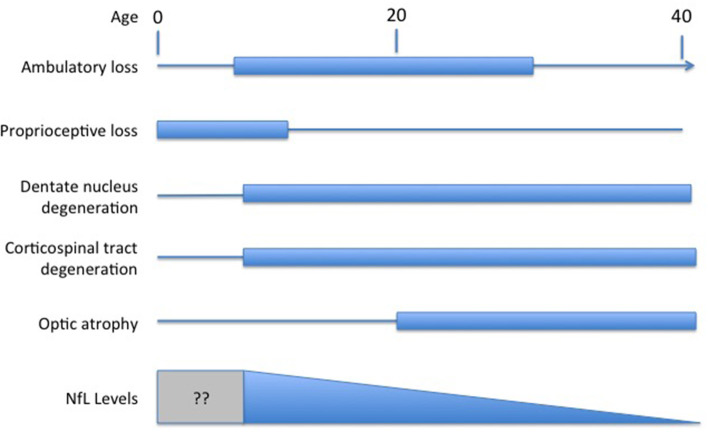

Understanding the exact meaning of NfL levels in serum and how they reflect disease activity in FRDA would facilitate their use as a marker of FRDA. In most other disorders, NfL is viewed as a marker of neurodegeneration of either axons or other neuronal regions. Degeneration in FRDA, though, is complex, including both peripheral nerve degeneration (including very early degeneration of proprioceptive afferents) with later degeneration of central nervous system axons; loss of central nervous system elements controls most of the clinical progression of the disease (Selvadurai et al., 2016; Koeppen et al., 2017a; Strawser et al., 2017; Marty et al., 2019; Rezende et al., 2019; Harding et al., 2020; Naeije et al., 2020). Brain imaging studies are typically normal early in disease, with the exception of atrophy of the cervical spinal cord, with progressive loss of CNS pathways later (Selvadurai et al., 2016; Koeppen et al., 2017b; Marty et al., 2019; Rezende et al., 2019; Harding et al., 2020; Naeije et al., 2020). Thus, serum NfL levels in FRDA, with high values early in disease, are discrepant from the tangible loss of CNS axons by MRI and the loss of specific functional clinical systems (Figure 1). The present data on serum NfL levels could be explained by a relatively large early loss of peripheral axons that does not contribute to clinical progression. Similarly, the inverse correlation with GAA repeat length in early disease might lead to a large developmental deficit at presentation. This in turn might lead to lower serum NfL levels during neurodegeneration. This interpretation would be consistent with the prevailing concept of NfL levels reflecting a relatively passive leakage from dying neurons into surrounding fluids and eventually to the serum.

Figure 1.

Temporal course of changes in FRDA. Diagram illustrating the contrasting temporal course of clinical changes in FRDA along with serum NfL levels over time (amalgamated from Bridel et al., 2019; Del Prete et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Clinical changes are presented based on the clinical course of an early onset individual (onset between ages 5−10). At present, no study has measured NfL in the presymptomatic period before age five.

Alternatively, increased levels of NfL could reflect other components of the pathophysiology of FRDA in a manner not directly associated with cell death. FRDA is associated with abnormalities in lipid metabolism as well as lipid peroxidation (Navarro et al., 2010; Obis et al., 2014; Abeti et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Tamarit et al., 2016; Cotticelli et al., 2019; Turchi et al., 2020). Both could lead to membranes that are inherently more permeable than normal, with consequent loss of NfL from the cell. Why these processes would decrease with age, however, is unclear.

Still, other processes might contribute to the paradox of elevated NfL levels early in FRDA. NfL levels must to some degree reflect its synthesis, as increased synthesis leads to higher levels of soluble NfL (before it is incorporated into neurofilaments) that should more readily efflux from neurons cells than NfL assembled into intact neurofilaments. Increased synthesis of structural proteins in axons occurs in response to injury and during neuronal regeneration (Pearson et al., 1988; Havton and Kellerth, 2001; Toth et al., 2008; Balaratnasingam et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016), and neurofilaments play different roles in development than simply structural maintenance. The very high levels of NfL early in FRDA could reflect attempts at regeneration that become more impaired as the disease progresses, leading to falling levels of NfL later in the course of the disorder. In general, the plasticity of the nervous system decreases with aging, matching the falls in serum NfL over time in FRDA (Bouchard and Villeda, 2015). Thus, elevated levels of serum NfL early in the course of FRDA could be driven by enhanced synthesis of NFL during regeneration superimposed on increased membrane fragility.

Interestingly, cardiac troponin levels are elevated in FRDA serum during the period of hypertrophic disease, long before cardiomyocytes die and cardiac fibrosis develops (Friedman et al., 2013; Plehn et al., 2018; Legrand et al., 2020). Such elevated levels of troponin in early FRDA cardiomyopathy might result from similar mechanisms to the elevated levels of NfL early in FRDA (Thebault et al., 2020).

A final possibility is that both cell-loss and cell-repair mechanisms—and possibly still other mechanisms—mediate the changes in NfL in FRDA. Such interpretations may only be distinguishable over time with collection of long-term serial data, and with collection of data during the presymptomatic period. Furthermore, a more complete characterization of the features of immunoreactive NfL in FRDA serum may be helpful. While the assays used are specific for NfL, they do not assess whether it represents full-length protein. This does not change the observation that Nfl levels can serve as biomarkers of disease in FRDA. However, without understanding the reason for the unusual distribution of NfL values, it is difficult to provide precise interpretations for clinical trial results. Normalization of biomarker levels can provide evidence for benefit in the correct circumstances, but can also reflect impairment of compensatory mechanisms, thus being associated with deleterious effects. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms of NfL elevation in serum in FRDA is needed to make it a useful biomarker in FRDA.

Author Contributions

BF created the first draft and edited the final work. RW and KS provided ideas, editing, and critical review. DL contributed to the first draft, performed critical review, ideas for the project, and designed the figure. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FRDA

Friedreich Ataxia

- NfL

Neurofilament light chain

- GAA

Guanine-adenine-adenine

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- CNS

central nervous system.

References

- Abeti R., Parkinson M. H., Hargreaves I. P., Angelova P. R., Sandi C., Pook M. A., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial energy imbalance and lipid peroxidation cause cell death in Friedreich's ataxia. Cell Death Dis. 7:e2237. 10.1038/cddis.2016.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas O., Renner A., Huss A., Filser M., Baetge S., Stute N., et al. (2020). Serum neurofilament light chain: no clear relation to cognition and neuropsychiatric symptoms in stable, M. S. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 7:e885. 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babady N. E., Carelle N., Wells R. D., Rouault T. A., Hirano M., Lynch D. R., et al. (2007). Advancements in the pathophysiology of Friedreich's Ataxia and new prospects for treatments. Mol. Genet. Metab. 92, 23–35. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaratnasingam C., Morgan W. H., Bass L., Kang M., Cringle S. J., Yu D. Y. (2011). Axotomy-induced cytoskeleton changes in unmyelinated mammalian central nervous system axons. Neuroscience 177, 269–282. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbella B., Reutenauer L., Monassier L., Puccio H. (2019). Correction of half the cardiomyocytes fully rescue Friedreich ataxia mitochondrial cardiomyopathy through cell-autonomous mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, 1274–1285. 10.1093/hmg/ddy427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bott C. J., Winckler B. (2020). Intermediate filaments in developing neurons: beyond structure. Cytoskeleton 77, 110–128. 10.1002/cm.21597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard J., Villeda S. A. (2015). Aging and brain rejuvenation as systemic events. J. Neurochem. 132, 5–19. 10.1111/jnc.12969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridel C., van Wieringen W. N., Zetterberg H., Tijms B. M., Teunissen CE., the NFL Group . (2019). Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 76, 1035–1048. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Ho T. S., Lin G., Tan K. L., Rasband M. N., Bellen H. J. (2016). Loss of Frataxin activates the iron/sphingolipid/PDK1/Mef2 pathway in mammals. Elife 5:e20732. 10.7554/eLife.20732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay A., Obrochta K. M., Soon R. K., Jr., Russell C. B., Lynch D. R. (2020). Neurofilament light chain as a potential biomarker of disease status in Friedreich ataxia. J. Neurol. 267, 2594–2598. 10.1007/s00415-020-09868-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin F., Martelli A., Clemancey M., Latour J. M., Gambarelli S., Zeppieri L., et al. (2013). Ollagnier de Choudens S. Mammalian frataxin controls sulfur production and iron entry during de novo Fe4S4 cluster assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 733–40. 10.1021/ja308736e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotticelli M. G., Xia S., Lin D., Lee T., Terrab L., Wipf P., et al. (2019). Ferroptosis as a novel therapeutic target for friedreich's ataxia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 369, 47–54. 10.1124/jpet.118.252759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBrosse C., Nanga R. P. R., Wilson N., D'Aquilla K., Elliott M., Hariharan H., et al. (2016). Muscle oxidative phosphorylation quantitation using creatine chemical exchange saturation transfer (CrCEST) MRI in mitochondrial disorders. JCI Insight 1:e88207. 10.1172/jci.insight.88207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete E., Beatino M. F., Campese N., Giampietri L., Siciliano G., Ceravolo R., et al. (2020). Fluid candidate biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: a precision medicine approach. J. Pers Med. 10:221. 10.3390/jpm10040221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatycki M. B., Bidichandani S. I. (2019). Friedreich ataxia- pathogenesis and implications for therapies. Neurobiol. Dis. 132:104606. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgrave L. M., Ma M., Best J. R., DeMarco M. L. (2019). The diagnostic performance of neurofilament light chain in CSF and blood for Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer's Dement. 11, 730–743. 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L. S., Schadt K. A., Regner S. R., Mark G. E., Lin K. Y., Sciascia T., et al. (2013). Elevation of serum cardiac troponin I in a cross-sectional cohort of asymptomatic subjects with Friedreich ataxia. Int. J. Cardiol. 167, 1622–1624. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding I., Lynch D. R., Koeppen A., Pandolfo M. (2020). Central nervous system therapeutic targets in friedreich ataxia. Hum. Gene Ther. 31, 1226–1236. 10.1089/hum.2020.264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havton L. A., Kellerth J. O. (2001). Neurofilamentous hypertrophy of intramedullary axonal arbors in intact spinal motoneurons undergoing peripheral sprouting. J. Neurocytol. 30, 917–926. 10.1023/A:1020669201697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayer S. N., Liepelt I., Barro C., Wilke C., Kuhle J., Martus P., et al. (2020). NfL and pNfH are increased in Friedreich's ataxia. J. Neurol. 267, 1420–1430. 10.1007/s00415-020-09722-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S. T., Kidd G. J., Crawford T. O., Xu Z., Lin W. M., Trapp B. D., et al. (1994). Regional modulation of neurofilament organization by myelination in normal axons. J. Neurosci. 14, 6392–6401. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06392.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen A. H., Becker A. B., Qian J., Feustel P. J. (2017b). Friedreich ataxia: hypoplasia of spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 76, 101–108. 10.1093/jnen/nlw111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen A. H., Becker A. B., Qian J., Gelman B. B., Mazurkiewicz J. E. (2017a). Friedreich ataxia: developmental failure of the dorsal root entry zone. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 76, 969–977. 10.1093/jnen/nlx087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurochkina N., Bhaskar M., Yadav S. P., Pant H. C. (2018). Phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and multiprotein assemblies regulate dynamic behavior of neuronal cytoskeleton: a mini-review. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:373. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand L., Maupain C., Monin M. L., Ewenczyk C., Isnard R., Alkouri R., et al. (2020). Significance of NT-proBNP and high-sensitivity troponin in friedreich ataxia. J. Clin. Med. 9:1630. 10.3390/jcm9061630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Polak U., Bhalla A. D., Lin K., Shen J., Farmer J., et al. (2015). Excision of expanded GAA repeats alleviates the molecular phenotype of friedreich's ataxia. Mol. Ther. 23, 1055–1065. 10.1038/mt.2015.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Liu Z., Liu H., Li H., Pan X., Li Z. (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes vesicular glutamate transporter 3 expression and neurite outgrowth of dorsal root ganglion neurons through the activation of the transcription factors Etv4 and Etv5. Brain Res. Bull. 121, 215–226. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi R., Hart P. E., Rajagopalan B., Taylor D. J., Crilley J. G., Bradley J. L., et al. (2001). Antioxidant treatment improves in vivo cardiac and skeletal muscle bioenergetics in patients with Friedreich's ataxia. Ann. Neurol. 49, 590–596. 10.1002/ana.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D. R., Chin M. P., Delatycki M. B., Subramony S. H., Corti M., Hoyle J. C., et al. (2021). Safety and efficacy of omaveloxolone in friedreich ataxia (MOXIe study). Ann. Neurol. 89, 212–225. 10.1002/ana.25934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D. R., Farmer J., Hauser L., Blair I. A., Wang Q. Q., Mesaros C., et al. (2018). Safety, pharmacodynamics, and potential benefit of omaveloxolone in Friedreich ataxia. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6, 15–26. 10.1002/acn3.660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch D. R., Regner S. R., Schadt K. A., Friedman L. S., Lin K. Y., St John Sutton M. G. (2012). Management and therapy for cardiomyopathy in Friedreich's ataxia. Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 10, 767–777. 10.1586/erc.12.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty B., Naeije G., Bourguignon M., Wens V., Jousmäki V., Lynch D. R., et al. (2019). Evidence for genetically determined degeneration of proprioceptive tracts in Friedreich ataxia. Neurology 93, e116–e124. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R., Korczyn A. D., Manouchehri N., Stüve O. (2020). The temporal and causal relationship between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 26, 876–886. 10.1177/1352458519886943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeije G., Bourguignon M., Wens V., Marty B., Goldman S., Hari R., et al. (2020). Electrophysiological evidence for limited progression of the proprioceptive impairment in Friedreich ataxia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 131, 574–576. 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro J. A., Ohmann E., Sanchez D., Botella J. A., Liebisch G., Moltó M. D., et al. (2010). Altered lipid metabolism in a Drosophila model of Friedreich's ataxia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2828–2840. 10.1093/hmg/ddq183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obis È., Irazusta V., Sanchís D., Ros J., Tamarit J. (2014). Frataxin deficiency in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes targets mitochondria and lipid metabolism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 73, 21–33. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore A., Puccio H. (2013). Frataxin: a protein in search for a function. J. Neurochem. 126(Suppl.1), 43–52. 10.1111/jnc.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R. C., Taylor N., Snyder S. H. (1988). Tubulin messenger RNA: in situ hybridization reveals bilateral increases in hypoglossal and facial nuclei following nerve transection. Brain Res. 463, 245–249. 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90396-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet F., de Montigny C., Vaucamps N., Reutenauer L., Eisenmann A., Puccio H. (2018). Rapid and complete reversal of sensory ataxia by gene therapy in a novel model of friedreich ataxia. Mol. Ther. 26, 1940–1952. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plehn J. F., Hasbani K., Ernst I., Horton K. D., Drinkard B. E., Di Prospero N. A. (2018). The subclinical cardiomyopathy of friedreich's ataxia in a pediatric population. J. Card Fail. 24, 672–679. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende T. J. R., Martinez A. R. M., Faber I., Girotto Takazaki K. A., Martins M. P., de Lima F. D., et al. (2019). Developmental and neurodegenerative damage in Friedreich's ataxia. Eur. J. Neurol. 26, 483–489. 10.1111/ene.13843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pascau L., Britti E., Calap-Quintana P., Dong Y. N., Vergara C., Delaspre F., et al. (2021). PPAR gamma agonist leriglitazone improves frataxin-loss impairments in cellular and animal models of Friedreich Ataxia. Neurobiol. Dis. 148:105162. 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rötig A., de Lonlay P., Chretien D., Foury F., Koenig M., Sidi D., et al. (1997). Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat. Genet. 17, 215–217. 10.1038/ng1097-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvadurai L. P., Harding I. H., Corben L. A., Stagnitti M. R., Storey E., Egan G. F., et al. (2016). Cerebral and cerebellar grey matter atrophy in Friedreich ataxia: the IMAGE-FRDA study. J. Neurol. 263, 2215–2223. 10.1007/s00415-016-8252-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawser C., Schadt K., Hauser L., McCormick A., Wells M., Larkindale J., et al. (2017). Pharmacological therapeutics in Friedreich ataxia: the present state. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 17, 895–907. 10.1080/14737175.2017.1356721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawser C., Schadt K., Lynch D. R. (2014). ataxia. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 14, 949–957. 10.1586/14737175.2014.939173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamarit J., Obis È., Ros J. (2016). Oxidative stress and altered lipid metabolism in Friedreich ataxia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 100, 138–146. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thebault S., Booth R. A., Freedman M. S. (2020). Blood neurofilament light chain: the neurologist's troponin? Biomedicines 8:523. 10.3390/biomedicines8110523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth C., Shim S. Y., Wang J., Jiang Y., Neumayer G., Belzil C., et al. (2008). Ndel1 promotes axon regeneration via intermediate filaments. PLoS ONE 3:e2014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou A. Y., Paulsen E. K., Lagedrost S. J., Perlman S. L., Mathews K. D., Wilmot G. R., et al. (2011). Mortality in Friedreich ataxia. J. Neurol. Sci. 307, 46–913. 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchi R., Tortolici F., Guidobaldi G., Iacovelli F., Falconi M., Rufini S., et al. (2020). Frataxin deficiency induces lipid accumulation and affects thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Cell Death Dis. 11:51. 10.1038/s41419-020-2347-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wang W., Shi H., Han L., Pan P. (2020). Cerebrospinal fluid and blood levels of neurofilament light chain in Parkinson disease: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 99:e21458. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F., Men C., Lu R., Li L., Zhang Y., Chen H., et al. (2014). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells repair spinal cord ischemia/reperfusion injury by promoting axonal growth and anti-autophagy. Neural. Regent Res. 9, 1665–1671. 10.4103/1673-5374.141801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlberger A. M., Thomas-Black G., Garcia-Moreno H., Foiani M., Heslegrave A. J., Zetterberg H., et al. (2018). Plasma markers of neurodegeneration are raised in friedreich's ataxia. Front. Cell Neurosci. 12:366. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zesiewicz T., Heerinckx F., De Jager R., Omidvar O., Kilpatrick M., Shaw J., et al. (2018a). Randomized, clinical trial of RT001: early signals of efficacy in Friedreich's ataxia. Mov. Disord. 33, 1000–1005. 10.1002/mds.27353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zesiewicz T., Salemi J. L., Perlman S., Sullivan K. L., Shaw J. D., Huang Y., et al. (2018b). Double-blind, randomized and controlled trial of EPI-743 in Friedreich's ataxia. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 8, 233–242. 10.2217/nmt-2018-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]