Summary

Autosomal recessive mutations in G6PC3 cause isolated and syndromic congenital neutropenia which includes congenital heart disease and atypical inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In a highly consanguineous pedigree with novel mutations in G6PC3 and MPL, we performed comprehensive multi-omics analyses. Structural analysis of variant G6PC3 and MPL proteins suggests a damaging effect. A distinct molecular cytokine profile (cytokinome) in the affected proband with IBD was detected. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based proteomics analysis of the G6PC3-deficient plasma samples identified 460 distinct proteins including 75 upregulated and 73 downregulated proteins. Specifically, the transcription factor GATA4 and LST1 were downregulated while platelet factor 4 (PF4) was upregulated. GATA4 and PF4 have been linked to congenital heart disease and IBD respectively, while LST1 may have perturbed a variety of essential cell functions as it is required for normal cell-cell communication. Together, these studies provide potentially novel insights into the pathogenesis of syndromic congenital G6PC3 deficiency.

Subject areas: Pathophysiology, Systems Biology, Genomics, Proteomics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Multi-omics approaches identify unique signatures

-

•

Whole-exome sequencing reveals distinct cytokine profiles

-

•

Expression of GATA4, PF4, and LST1 is dysregulated

Pathophysiology ; Systems Biology ; Genomics ; Proteomics ;

Introduction

Several familial syndromes can present with neutropenia including severe congenital neutropenia, or Kostmann syndrome, cyclic neutropenia, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis syndrome, Barth syndrome (X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy with neutropenia), poikiloderma with neutropenia, and glycogen storage disease type 1b, among others (Banka, 2016). The severity and pattern of neutropenia, the nature of complications, and the co-existing non-hematological phenotypes all assist in making the likely correct clinical diagnosis.

Mutations in several genes including ELANE and HAX1 (being the most common) have been identified as causes of severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) (Dale et al., 2000; Klein et al., 2006). The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based mutation analysis allows comprehensive testing of patients with neutropenia of different etiologies. Consequently, more patients with monogenic SCN neutropenia including G6PC3 deficiency are likely to be diagnosed.

G6PC3 (glucose-6-phosphatase, catalytic, subunit 3) mutations have been identified as a cause of congenital neutropenia, initially in 2 consanguineous pedigrees (Boztug et al., 2009). Since then, over 90 cases have been described, and the spectrum of disease phenotype has been reviewed (Banka, 2016; Banka and Newman, 2013). The glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme is involved in glycogenolysis, with 3 known catalytic subunits being present in humans. G6PC3 encodes the glucose-6-phosphatase enzyme which is expressed ubiquitously in humans, in contrast to G6PC1 (expressed in the small intestine) and G6PC2 (expressed in the liver). The G6PC3 gene maps to chromosome 17q21 (GRCh38:44,070,699-44,076,343) and consists of 6 exons.

G6PC3 deficiency may manifest as (i) a non-syndromic SCN, (ii) the so-called classic G6PC3 deficiency with SCN and cardiovascular and/or urogenital abnormalities, or (iii) the more severe form, known as the Dursun syndrome, involving non-myeloid hematopoietic cell lineages and neonatal pulmonary hypertension and thymic hypoplasia (Banka et al., 2010; Dursun et al., 2009). Inflammatory bowel (like) disease has been reported in some cases and small series with G6PC3 deficiency (Begin et al., 2012; Cullinane et al., 2011; Desplantes et al., 2014; Glasser et al., 2016). Hypo-glycosylation of gp91phox, the electron-transporting component of the NADPH oxidase, had been demonstrated in patients with neutropenia and G6PC3 deficiency (Hayee et al., 2011). Failure to eliminate the phosphorylated glucose analog (1,5-anhydroglucitol-6-phosphate; 1,5AG6P) was found to cause neutropenia in patients with G6PC3 deficiency (Veiga-da-Cunha et al., 2019). Activating mutations in THPO and MPL are also known to cause thrombocytosis which may predispose to thromboembolism (Dasouki et al., 2015).

Proteomics studies are being increasingly used in the search for biomarkers for many human diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Several proteomics studies suggested different protein signatures which were identified in serum, feces, and colonic epithelia of affected patients (summarized in Bennike et al., 2014). Examples of these diverse biomarkers include anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies, perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, C-reactive protein, calprotectin, lactoferrin, annexin A1, lymphocyte cytosolic protein 1 (aka L-plastin), proteasome activator subunit 1, and many others.

In this study, we performed extensive whole-exome and proteome analyses (with special emphasis on the cytokinome) in 3 consanguineous family members from Southern Saudi Arabia (Figure 1) with G6PC3 deficiency and secondary (atypical) IDB and thrombocytosis. We identified novel mutations in G6PC3, MPL as well as multiple cytokines and novel proteomic biomarkers. This complex and unique multi-omic fingerprint may help improve the understanding of the mechanisms and help identify novel treatment opportunities.

Figure 1.

Family pedigree and Sanger sequencing

The large consanguineous family with G6PC3 deficiency has 3 affected patients (2 sisters: IV-1, 2 and their double cousin, IV.6). The Sanger sequencing chromatograms show homozygosity (indicated −/−) and heterozygosity (+/−) for the novel G6PC3 mutation. The novel MPL heterozygous mutation is also shown as (+/−) in multiple family members including IV.6.

Results

Clinical and molecular analyses

The clinical features and results of routine clinical investigations are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. While all 3 G6PC3-deficient patients had severe failure to thrive and very low body mass index, only patient IV.6 had been diagnosed with IBD (atypical Crohn disease). Recurrent chest infections and resultant bronchiectasis and secondary pulmonary hypertension occurred in siblings IV.1 and 2 but not their cousin (IV.6). All 3 patients had congenital heart disease (atrial septal defect) requiring repair in patient IV.6. Pan-T-cell lymphopenia was found in two patients (IV.2, and IV.6). Interestingly, serum IgE deficiency in combination with hyper-gammaglobulinemia was present in all 3 G6PC3-deficient patients in this family. However, no mutations in IGHE (which encodes IgE) or its receptors (FCER1A, MS4A2, FCER1G; FCER2) were found. A common variant in MS4A2 (which encodes FCER1B) previously thought to predispose to atopy was found in 2 of the 3 patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of individuals affected with G6PC3 deficiency.

| Clinical manifestations | Patient IV.1 | Patient IV.2 | Patient IV.6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infections | Skin and chest | Skin and chest | Skin; otitis media; recurrent E.coli UTI and abdominal sepsis | |

| GI | Childhood FTT, diarrhea/steatorrhea; no bowel symptoms in adulthood | Childhood FTT, diarrhea/steatorrhea; no bowel symptoms in adulthood | Childhood FTT, diarrhea/steatorrhea; severe IBD with stricture disease | |

| Respiratory | Bronchiectasis, class 1 pulmonary hypertension | Bronchiectasis, respiratory failure, class IV pulmonary hypertension; lung transplantation candidate | Not significant | |

| Cardiac | Fenestrated ASD with bidirectional flow (mainly left to right); moderately dilated RA, RV, and main PA | Dilated RV with RVH, TR, raised RVSP | ASD repaired at age 8 | |

| Skeletal | Generalized osteopenia; underdeveloped sinuses | Microcephaly, mid face hypoplasia; thoracic spine kyphosis; generalized osteopenia | Oligoarthritis, generalized osteopenia, facial dysmorphism | |

| Growth | Weight | 25.9 kg at age 17 | 29.4 at age 16 | 17kg at age 20 |

| BMI | 14 | 12.7 | 11.6 | |

| Height | <3rd centile | <3rd centile | <3rd centile | |

ASD, atrial septal defect; BMI, body mass index; FTT, failure to thrive; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PA, pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

Table 2.

Routine laboratory investigations

| Laboratory results | Patient IV.1 | Patient IV.2 | Patient IV.6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil count x109/L, Median (range) | Pediatric: 0.5 (0.11–2.25) | Pediatric: 0.31 (0.09–1.76) | Pediatric: 1.39 (0.8–6.2) |

| Adult: 0.34(0.24–1.77)a | Adult 2.385 (0.4–4.57)a | Adult: 1.65 (0.67–17.2) | |

| Lymphocyte x109/L, median (range) | 2.95 (1.59–3.27) | 2.4 (1.2–8.5) | 0.49 (0.14–2.17) |

| Platelet counts, x109/L, median (range) | 498 (344–777) | 392 (179–738) | 498 (150–1074) |

| Hb g/L, median (range) | 108 (84–130) | 100 (77–127) | 97 (58–147) |

| Bone marrow | Pediatric: Unremarkable with no maturation arrest | Pediatric: marked left-shifted granulopoiesis and active erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis | – |

| Adult: hypoplastic myelopoiesis and left shift with abnormal segmentation of myeloid precursors | Adult: myeloid hyperplasia, left shifted and minimal maturation and some with increased granulation | Adult: Left shifted myelopoiesis | |

| Bone marrow karyotype | 46, XX | 46, XX | 46, XX |

| IgA (normal: 0.7 - 4 g/L) | 1.9 | 2.93 | 1.72 |

| IgG (normal: 7–16 g/L) | 27.8 | 56.6 | 23.3 |

| IgM (normal: 0.4-2.3 g/L) | 0.63 | 0.77 | 2.5 |

| IgE (normal: 5–500 KU/L) | <2 | <2 | 2.5 |

| T-cell subsets | Normal T-cell subsets | T-cell lymphopenia; intact expression of MHC class I and Il antigens | Absolute CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell lymphopenia |

Initial (pediatric) studies were done in early childhood (3–5 years of age). Follow-up (adult) studies were done between 14 and 17 years of age.

Sanger sequencing of the CFTR and SBDS genes was negative. Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the 3 patients' exomes are listed in Table 3. All 3 patients were homozygous for a novel homozygous missense mutation in exon 4 of G6PC3 (c.479C > T, p.Ser160Leu) which was also confirmed by Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis (Figure 1). This mutation has not previously been reported in the homozygous state in various public databases including dbSNP, 1000G, ESV, ExAC, gnomAD, and our private Saudi Genome Program database (https://www.saudigenomeprogram.org/). Only a single (African) heterozygous individual (allele frequency: 0.000004061) was recently identified in the gnomAD database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

Table 3.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in the 3 patients' exomes including cytokinome profiles

| Genea (mutation/variant) | Disease associationa | Patient IV.1 | Patient IV.2 | Patient IV.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G6PC3:NM_138387:exon4:c.479C > T:p.S160L | SCN4 (AR), Dursun syndrome | hmz | hmz | hmz |

| MPL:NM_005373:exon4:c.398C > T:p.P133L | CAMT (AR), thrombocythemia (AD), MFMM (som) | wt | wt | het |

| HBG1:NM_000559:c.6_a3delinsCTCT | HbF (QTL1) | hmz | hmz | hmz |

| KLF1:NM_006563:exon2:12996130-12996956:-14:840 | HPFH (AD), CDA type 4 | wt | wt | hmz |

| MS4A2 (FCER1B): NM_001256916:exon6:c.575A > G:p.E192G | susceptibility to atopy | het | wt | hmz |

| CCL15:NM_032965:exon1:c.5A > T:p.K2M | None | hmz | hmz | hmz |

| CXCR2:NM_001557:exon3:c.1075A > T:p.T359S | None | wt | het | het |

| IFNAR1:NM_000629:exon8:c.1143 + 12G > A | None | het | wt | wt |

| IFNAR2:NM_000874:exon7:c.611C > G:p.T204R | IMD45 (AR) | het | wt | wt |

| IFNW1:NM_002177:exon1:c.247A > G:p.M83V | None | wt | wt | het |

| IL10RA:NM_001558:exon1:c.67 + 11G > C | IBD28 (AR) | het | wt | het |

| IL16:NM_172217:exon4:c.643T > C:p.S215P | None | het | wt | het |

| IL18R1:NM_003855:exon6:c.626-7C > T | None | het | wt | het |

| IL1R1:NM_001288706:exon12:c.1211-4T > C | None | het | wt | het |

| IL1RL1:NM_016232:exon11:c.1501_1502delinsAG | None | het | wt | het |

| IL21R:NM_021798:exon9:c.1381dupG:p.A460fs | IMD56 (AR), high IgE (AD) | het | wt | wt |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CAMT, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia; CDA, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia; CCL15, chemokine, cc motif, ligand 15; CXCR2, chemokine, CXC motif, receptor 2; G6PC3, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic 3; HBG1, hemoglobin gamma A; het, heterozygous mutant; hmz, homozygous mutant; HPFH, hereditary persistent fetal hemoglobin; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IMD, immunodeficiency; IFNAR1, interferon-alpha-beta- and omega receptor 1; IFNAR2, interferon-alpha-beta- and omega receptor 2; IFNW1, interferon, omega-1; IL10RA, interleukin 10 receptor alpha; IL16, interleukin 16; IL18R1, interleukin 18 receptor-1; IL1R1, interleukin 1 receptor-1; IL1RL1, interleukin 1 receptor-like 1; IL21R, interleukin-21 receptor; KLF1, Kruppel-like factor 1; MFMM, myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia; MPL, myeloproliferative virus oncogene; QTL, quantitative trait locus; SCN, severe congenital neutropenia; som, somatic; wt, wild type.

Cytokinome refers to patient-specific rare DNA variants.

Disease-gene association data are based on OMIM database “www.omim.org”.

Also, a homozygous c.154C > T (p.Arg52Cys) missense variant in exon 1 of MBL2 was observed in patient IV.1. In silico analysis of this variant also predicted it to be damaging and has been associated with MBL2 deficiency which is reported to be common in Caucasians (Choteau et al., 2016).

Additionally, the exome of patient IV.6 (but not her cousins IV.1 and 2) showed a very rare (allele frequency: 3.255 × 10−5), possibly damaging heterozygous MPL variant (Chr1:43804948:43804948: NM_005373:exon4:c.398C > T, p.P133L) which was also confirmed by Sanger sequencing and segregation analysis (Figure 1). While all 3 patients had intermittent thrombocytosis, it was most marked in patient IV.6.

Interestingly, we also detected a novel homozygous mutation in HBG1 (NM_000559: c.∗6_∗3delinsCTCT) in all 3 affected G6PC3-deficient patients in addition to another novel homozygous splicing mutation in KLF1 (NM_006563:exon2:12996130-12996956:-14:840; GC > −) in patient IV.6 only which probably explains the elevated HbF levels observed in these patients.

In silico structural analysis of G6PC3 and MPL mutations

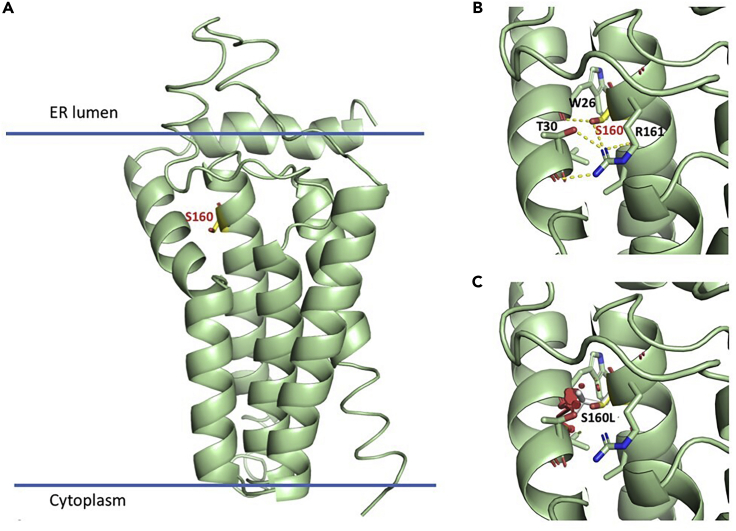

G6PC3 is a 346-amino acid protein, predicted to contain nine transmembrane helices that span the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, with the active site lying inside the ER lumen (Ghosh et al., 2004). Prediction of the 3D protein structure based on different threading templates such as the crystal structure of the transmembrane PAP2 type phosphatidylglycerol phosphate phosphatase from Bacillus subtilis (see transparent methods) revealed that Ser160 is located close to the end of the fourth transmembrane helix, near the ER luminal side. Ser160 is in close contact with neighboring helix 1 and is predicted to be involved in buried hydrogen bond intramolecular interactions with Arg161, Thr30, and the backbone carbonyl of Trp26 (Figure 2, G6PC3-A, B). Thus, Ser160 plays an important role in tethering helices 1 and 4 together. The mutation Ser160Leu would disrupt this interaction network and cause steric clashes (Figure 2, G6PC3-C). Hence, Ser160Leu would destabilize the interface between helices 1 and 4 and thus affect the tertiary structure of this region, which could reduce the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme or the efficiency of coupling to the transporter protein glucose 6-phosphate translocase (SLC37A4).

Figure 2.

Computational assessment of the impact of the G6PC3 mutation

(A) Homology model produced with I-TASSER of the region comprising the residues 1–195. Ser160 is highlighted as yellow stick model, and the orientation of the protein with respect of the ER membrane is shown.

(B). Predicted intramolecular interactions between helices 1 and 4, mediated by Ser160. Hydrogen bonds are indicated with dashed lines.

(C) The substitution of Ser160 for leucine (gray sticks) would destabilize the interface between the two helices, altering the tertiary structure of the region.

The amino acid residue Pro133 maps to the extracellular domain of MPL which contains two cytokine receptor homology regions (CHRs), each composed of two fibronectin type III (FNIII) domains. Pro133 is part of the linker connecting the first and second FNIII of the N-terminal CHR (CHR1). The structure of this CHR1 region can be inferred based on a ∼28% sequence identity with the erythropoietin receptor (Figure 3, MPL-A). Computational modeling suggests that substituting Pro133 by a larger and more hydrophobic leucine affects the stability and dynamics of this region (Figure 3; MPL-B). Given that the relative orientation of the FNIII domains critically affects signaling through cytokine receptors (Syed et al., 1998), the Pro133Leu mutation is expected to perturb MPL activation and signaling.

Figure 3.

Computational assessment of the impact of the MPL mutation

(A) Shown is the homology model of MPL CHR1 (magenta), produced based on the 28% identical structure of the CHR of EPOR (gray) bound to erythropoietin (yellow; PDB id 4cn4). Pro133 is highlighted as a green sphere model.

(B) Zoom into the region of Pro133 (shown as a green stick model). The substitution of Pro133 by a leucine (orange) would increase the hydrophobic interaction and hence structural and dynamic coupling of both FNIII domains of CHR1. CHR, cytokine receptor homology region; EPOR, erythropoietin receptor; FNIII, fibronectin type III; MPL, myeloproliferative leukemia virus oncogene.

Protein expression changes between G6PC3-deficient patients and control subjects

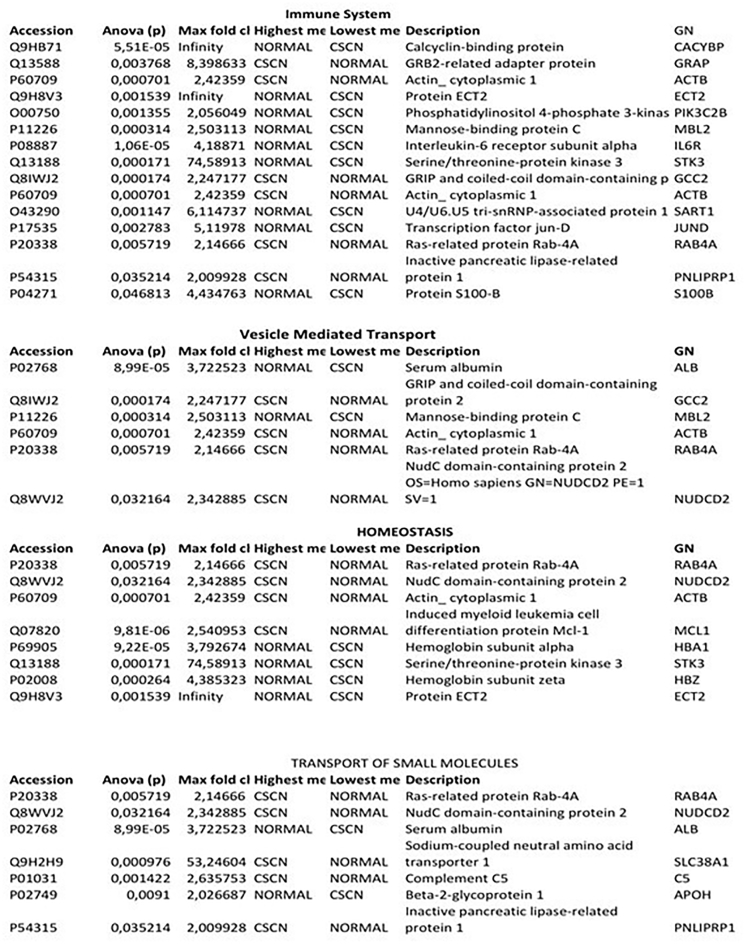

Peripheral blood plasma samples from the 3 subjects diagnosed with G6PC3 deficiency causing complex neutropenia in addition to IBD in patient IV.6, as well as 6 healthy subjects, were analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). A total of 460 unique protein species were identified (Table S1) of which 148 were significantly differentially expressed (≥2 to ∞: fold change and p < 0.05) between G6PC3 deficient and normal control subjects (Table S2). Classification of those 148 proteins based on their biological processes and molecular functions identified 4 major groups including the immune system, homeostasis, small molecule transport, and vesicle-mediated transport, respectively (Figures 4, 5, and 6). However, a 21-protein subpanel was represented in the pathway analysis of multiple signaling networks using the ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA, Qiagen) (Figures 7 and 8, networks 1 and 2, respectively) and STRING network database analysis tools (Figure 9). The functional annotations and the expression profiles and other characteristics of these proteins are detailed in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Biological process and molecular functional classification of the 148 differentially expressed proteins between CSN and control samples

Immune system- (16) and homeostasis (9)-related proteins were most the commonly represented.

Figure 5.

Biological process and molecular functional classification of the 148 differentially expressed proteins between CSN and control samples

Figure 6.

Differential protein expression in patients with G6PC3 deficiency

Heatmap of protein expression in 3 patients with severe congenital neutropenia (CSN) caused by G6PC3 deficiency and 6 healthy controls. Patient plasma samples and controls were pooled separately and run in triplicates.

Figure 7.

IPA network analysis of differentially expressed proteins in G6PC3 deficiency

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)-based network 1 of the 148 differentially expressed protein panel. The network is displayed graphically as nodes (gene/gene products) and edges (the biological relationship between nodes). The node color intensity indicates the expression of genes: red is upregulated and green is downregulated in plasma. The fold change values of differentially expressed proteins are indicated under each corresponding node. Node shapes indicate the functional class of the gene product as shown in the key.

Figure 8.

IPA networks analysis of differentially expressed proteins in G6PC3 deficiency

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)-based network 2 of the 148 differentially expressed protein panel. The network is displayed graphically as nodes (gene/gene products) and edges (the biological relationship between nodes). The node color intensity indicates the expression of genes: red is upregulated and green is downregulated in plasma. The fold change values of differentially expressed proteins are indicated under each corresponding node. Node shapes indicate the functional class of the gene product as shown in the key.

Figure 9.

The inter-relationships and functional characteristics of some of the 21 identified proteins as mapped in STRINGS pathway analysis database

Some of these molecules function as enzymes, coagulation factors, transporters, transcription regulators, and homeostasis and differentiation regulators. Others act as kinases, peptidase or growth factors, and cytokines. (The connecting network analyses were done, and the above figures were generated in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis program [IPA, version 8.7] and string, respectively). AGT, angiotensinogen; AKT1, AKT serine/threonine kinase 1; BCL2L11, BCL2-like 11; C1QA, complement component 1, q subcomponent, A chain; C1QB, complement component 1, q subcomponent, B chain; C2, complement component 2; F9, coagulation factor IX; FOS, FOS protooncogene; FOSB, FOSB protooncogene; FOSL1, FOS-like antigen 1; FOSL2, FOS-like antigen 2; HBA1, hemoglobin-alpha locus 1; HBB, hemoglobin-beta locus; IL6, interleukin 6; IL6R, interleukin 6 receptor; JUND, oncogene JUN-D; MCL1, myeloid leukemia sequence 1; PIK3CG, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic gamma; REN, renin; SERPINC1, serpin peptidase inhibitor clade C (antithrombin) member 1.

Interestingly, several globin chain proteins (HBA1, HBB, HBD, and HBZ) as well as immune-related proteins (C6, IL6R, LST1, JCHAIN, MBL2, and TRGC2) were downregulated. However, the neutrophil defensins, DEFA1, DEFA4, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (LCN2) were not differentially expressed. In addition, several downregulated proteins associated with known monogenic disorders were found including C6 (complement 6 deficiency), angiotensinogen (hypertension, renal tubular dysgenesis), GATA4 (congenital heart disease), thalassemia (HBA1, HBB, HBD, HBZ), MBL2 (chronic infections), PLOD2 (Bruck syndrome 2), SERPINF1 (osteogenesis imperfecta type VI, OI6), and WASHC4 (autosomal recessive mental retardation, MR41).

Perturbation of glutathione homeostasis is also evidenced by the dysregulation of the key enzymes glutathione peroxidase (GPX3) and glutaredoxin 2 (GLXR2) which were upregulated and downregulated, respectively. GPX3, glutathione peroxidase, is a plasma protein that protects cells, enzymes, and lipids against oxidative stress (peroxidation). GLRX2, glutaredoxin 2, is a glutathione-dependent hydrogen donor for ribonucleotide reductase with a predominantly nuclear and a minor mitochondrial isoform (Lundberg et al., 2001); upon oxidative stress, the iron-sulfur cluster serves as a redox sensor for the activation of GLRX2 (Lillig et al., 2005).

Kynurenine formamidase (AFMID) was significantly overexpressed, and kynurenine was elevated (unpublished data) suggesting a perturbation in tryptophan catabolism.

Discussion

We describe here a highly consanguineous pedigree with a novel exon 4 mutation in G6PC3 associated with a variably severe phenotype not concordant with the severity of neutropenia. G6PC3-related neutropenia is thought to be a rare entity, but given the varying severity of the disorder, from cyclical neutropenia to a severe life-threatening immunocompromised state and the spectrum of non-hematological complications, it is almost certainly underdiagnosed. It is also likely that in patients where the cardiac, neurodevelopmental, and gastrointestinal manifestations are more severe than the degree of neutropenia, which may be mild or near normal such as in our index case-patient IV.1, SCN may not be suspected at all. The (novel) G6PC3 exon 4 mutation we identified in this family has not, to our knowledge, been previously reported and may represent a candidate founder mutation, leading to a phenotype consistent with previous reports of G6PC3 mutations most of which impair its enzyme activity. Lin et al. (2015) showed that 14 out of 16 missense G6PC3 mutations abolished its enzymatic activity. Indeed, our computational structural analysis suggests that this novel mutation destabilizes the protein's 3D structure and stability at the ER luminal side. Recently, an unrelated Saudi Arabian pedigree was reported with a c.974T > G, p.Leu325Arg mutation and thrombocytopenia (Alangari et al., 2013). Conversely, we observed in our family thrombocytosis in association with neutropenia. While both thrombocytopenia and thrombocytosis may be seen clinically in sick individuals and are usually attributed to a toxic effect on myelopoiesis, alternatively, this effect may be mediated via variant(s) in the MPL-THPO axis (Dasouki et al., 2015). We, therefore, examined the gDNA from these 3 affected individuals for possibly damaging mutations and identified a rare heterozygous, potentially damaging, activating MPL mutation (c.398C > T, p.P133L). Our structural analysis localized it in a region involved in binding to its THPO ligand and hence predicted that it affects ligand recognition and signal initiation. Previously, it was shown that the deletion of the MPL CHR1 region has activating effects (Sabath et al., 1999), whereas point mutations in this region can have opposing effects, resulting in either gain or loss of function (Stockklausner et al., 2015). In the family reported by Alangari et al., no mutation analysis of MPL or THPO was reported.

In this progeny, we noticed striking variability in phenotype and disease severity arising from the same mutation. We suspect that other genomic and epigenetic variations likely account for these phenotypic differences. The list of genotypes for multiple loci identified in their exomes shown in Table 3 might explain additional hematological phenotypes such as elevated HbF and thrombocytosis, immune phenotypes such as low serum IgE levels and hypergammaglobulinemia, and the IBD phenotype.

Serum IgE deficiency is defined as an isolated significant decrease (<2.5 KU/L) in serum IgE level (combined with normal levels of other immunoglobulins). While selective serum IgE deficiency is still not recognized as a primary immunodeficiency disorder, it has been detected in seemingly healthy individuals, as well as in association with certain infections, sinopulmonary disease, non-allergic airway disease, autoimmunity, and various immunodeficiencies. In Lta (lymphotoxin) knockout mice, diminished serum IgE levels were associated with non-allergic Th1-mediated inflammatory airway disease (Kang et al., 2003). Also, IgE (a mucosal antibody) had been shown to possess antitumor activities both in vitro against pancreatic cancer (Fu et al., 2008; Reali et al., 2001) and in mouse models (Nigro et al., 2009; Daniels-Wells et al., 2013). These data suggest that serum IgE deficiency detected in our G6PC3-deficient patients may not be a completely benign finding.

Mutations in the mannose-binding lectin 2 (MBL2) have been implicated in predisposition to recurrent infections, albeit not consistently. Up to 10% of healthy individuals may have mannose-binding lectin deficiency (MBLD) and be asymptomatic. Moreover, variants have been associated with MBLD and a more severe phenotype in Crohn disease (Choteau et al., 2016).

In addition to the G6PC3 deficiency-related neutropenia and MBL2 deficiency, additional (environmental, genetic, and epigenetic) factors likely contributed to the recurrent chest infections and bronchiectasis observed in individuals IV.1 and 2. Although deaths due to respiratory failure have been reported, there are no reports to our knowledge of lung transplantation in individuals with G6PC3 deficiency (Desplantes et al., 2014).

The human neutrophil proteome contains approximately 4100 proteins, including 7 which account for 50% including the antimicrobial proteins DEF3A, S100A8, LYZ, and CTSG being among the most abundant (Grabowski et al., 2019) which we did not detect in our proteomics study. However, we detected the neutrophil defensins, DEFA1, DEFA4, and LCN2 which were not differentially expressed. In addition to our study and the study of Grabowski et al. (2019), we could not find any other proteomics studies that examine monogenic neutropenia. The neutrophil-based proteomic biomarkers they detected in SCN, chronic granulomatous disease, and leukocyte adhesion deficiency 1 and 2 caused by mutations in ELANE, CYBA and CYBB, and ITGB2 and SLC35C1, respectively, were disease specific and did not overlap with the profile caused by G6PC3 deficiency.

In our G6PC3-deficient individuals, in addition to congenital neutropenia which results in the loss of the known antimicrobial functions of neutrophils, we observed dysregulation of additional factors that may have exacerbated this primary defect, including the leukocyte-specific transcript 1 (LST1), the (myeloid specific) monocyte-specific differentiation factor (CD14), and MBL2 that have diverse immune functions.

LST1 is an extensively alternatively spliced major histocompatibility class (MHC) III gene with 13 (800-nucleotide) interferon gamma-inducible transcripts and is expressed in lymphoid tissues, T cells, macrophages, and histiocyte cell lines (Holzinger et al., 1995; Weidle et al., 2018). LST1 promotes the assembly of intercellular tunneling nanotube formation (Schiller et al., 2012) which used is for the transfer of organelles (Rustom et al., 2004), soluble markers (Watkins and Salter 2005), and electrical signals (Wang et al., 2010). Recently, the myeloid leukocyte-specific transmembrane LST1/A isoform was shown to function as an adapter protein that recruits the protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 to the plasma membrane, thus effecting negative regulation of signal transduction which is necessary for controlling the cell response (Draber et al., 2013). Also, the proinflammatory expression of LST1 in human IBD and non-IBD colitis was shown not to be restricted to immune cell populations (Heidemann et al., 2014). Taken together, this evidence strongly suggests a significant role for LST1 in the pathogenesis of immune dysfunction in G6PC3 deficiency.

Several patients with G6PC3 deficiency and IBD or IBD-like disorder have been described, although the mechanism(s) of this association is not known (Begin et al., 2013; Chandrakasan et al., 2017). In Table 3, we hypothesize that the novel genomics-based immune/cytokine signature profile which we identified in patient IV.6 but not in her two cousins without IBD is potentially IBD related. However, additional confirmatory studies are needed. Infliximab, a chimeric anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody, is used to treat patients with various autoimmune disorders including IBD (Crohn disease). Similarly, as reported by Begin et al., infliximab resulted in clinical improvement, albeit transient. Platelet factor 4 (PF4, CXCL4) is an index of platelet activation and thromboembolic risk (Simi et al., 1987). Elevated plasma and colonic mucosa PF4 levels correlated with disease activity (Simi et al., 1987; Ye et al., 2017; Sobhani et al., 1992) and response to treatment with infliximab in patients with IBD (Crohn disease) (Meuwis et al., 2008). Consequently, the upregulation of plasma PF4 levels we observed in this study may have a similar implication.

The GATA factors (1–6) are zinc-finger ‘WGATAR’ DNA motif binding proteins that regulate diverse pathways associated with embryonic morphogenesis and cellular differentiation (Patient and McGhee, 2002). GATA4 is essential for cardiac morphogenesis as well as the development of the liver, pancreas, and swim bladder (Holtzinger and Evans, 2005). Heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in GATA4 are associated with a variety of cardiac malformations including (atrial, ventricular, and atrioventricular) septal defects and tetralogy of Fallot (Garg et al., 2003). The finding of low expression of GATA4 in the plasma of our 3 patients with G6PC3 deficiency and congenital heart disease suggests a link which requires additional studies.

Conclusions

G6PC3 deficiency is a complex multisystem disorder with neutropenia as the main phenotype and IBD-like disease having been described in some patients. Proteomics profiling in monogenic neutropenia is disease specific. Using extensive genomics (including genomic cytokine profiling) and proteomics analyses, we identified a unique IBD-related profile including perturbations in several cytokines, LST1. We also observed the downregulation of GATA4 which may potentially explain the congenital heart disease seen in some patients with G6PC3 deficiency. Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of soluble and membrane-expressed LST1 and GATA-mediated phenotypic defects as well as the role of kynurenine in the regulation of mucosal intestinal immunity and inflammation.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we used genome-wide (exome) and MS-based plasma proteomics analyses to identify genomic and proteomic alterations in a highly consanguineous family with G6PC3 deficiency-related complex phenotypes. Apart from the novel G6PC3 and MPL variants which are likely to be directly related to the patients phenotypes and given the small sample size and incomplete knowledge about the other genomic variants shown in Table 3 and potential complex interactions between them, their exact role in this complex disease cannot be confirmed. Although MS-based comparative proteomics has increasingly become a powerful tool for biomedical research of complex monogenic and polygenic disorders, its analytical depth is still limited and several biochemical pathways playing a role in neutrophil dysfunction may have not been detected. Also, changes in protein abundance alone cannot characterize the entire pathology or underlying mechanism(s) of a complex disease like syndromic G6PC3 deficiency. The use of fully characterized healthy controls, which we could not use in our proteomics study, is highly desirable as it is more likely to reveal real differences in expression not related to genetic background. Also, the pooling of patients' plasma samples prevented us from potentially correlating specific differentially expressed proteins with varying clinical phenotypes.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Majed Dasouki, MD, Department of Genetics, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, MBC-03-30. PO Box 3354. Riyadh, 11,211. Saudi Arabia, Current email: majed.dasouki.md@adventhealth.com.

Material availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

The published article includes all data sets/code generated or analyzed during this study.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the clinicians who provided routine clinical care for these patients and thank the patients and their families who participated in this project. We also acknowledge the Saudi Human Genome Project for infrastructure and informatics support relating to the NGS work. The work by M.D., F.A., H.A., M.A., S.O.A. was supported by the National Science, Technology, and Innovation Plan program of King Abdulaziz City for Science & Technology (KACST), Saudi Arabia, award number: 13-BIO1978-20. The work by S.T.A. and F.J.G.V. was supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Saudi Arabia through the Award No. FCC/1/1976-25 from the Office of Sponsored Research (OSR).

Author contributions

M.J.D. and S.O.A. contributed in study design, supervision, and manuscript writing; A.A.A., Z.S., and M.J.D. contributed in proteomic studies; T.E., M.A., D.M., A.J., F.A., and M.J.D. contributed in genomic molecular and bioinformatics studies; S.T.A. and F.J.G.V. contributed in protein structural analysis; M.S.A., H.A.S., and S.O.A. contributed in clinical studies. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 19, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102214.

Supplemental information

References

- Alangari A.A., Alsultan A., Osman M.E., Anazi S., Alkuraya F.S. A novel homozygous mutation in G6PC3 presenting as cyclic neutropenia and severe congenital neutropenia in the same family. J. Clin. Immunol. 2013;33:1403–1406. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banka S. G6PC3 deficiency. In: Pagon R.A., Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Wallace S.E., Amemiya A., Bean L.J.H., Bird T.D., Fong C.T., Mefford H.C., Smith R.J.H., editors. GeneReviews(R) 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285321/ [Google Scholar]

- Banka S., Newman W.G. A clinical and molecular review of ubiquitous glucose-6-phosphatase deficiency caused by G6PC3 mutations. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:84. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banka S., Newman W.G., Özgül R.K., Dursun A. Mutations in the G6PC3 gene cause Dursun syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:2609–2611. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bégin P., Patey N., Mueller P., Rasquin A., Sirard A., Klein C., Haddad É., Drouin É., Le Deist F. Inflammatory bowel disease and T cell lymphopenia in G6PC3 deficiency. J. Clin. Immunol. 2012;33:520–525. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennike T., Birkelund S., Stensballe A., Andersen V. Biomarkers in inflammatory bowel diseases: Current status and proteomics identification strategies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3231. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boztug K., Appaswamy G., Ashikov A., Schäffer A.A., Salzer U., Diestelhorst J., Germeshausen M., Brandes G., Lee-Gossler J., Noyan F. A syndrome with congenital neutropenia and mutations in G6PC3. New Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:32–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrakasan S., Venkateswaran S., Kugathasan S. Nonclassic inflammatory bowel disease in young infants. Pediatr. Clin. North America. 2017;64:139–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choteau L., Vasseur F., Lepretre F., Figeac M., Gower-Rousseau C., Dubuquoy L., Poulain D., Colombel J.-F., Sendid B., Jawhara S. Polymorphisms in the mannose-binding lectin gene are associated with defective mannose-binding lectin functional activity in Crohn’s disease patients. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29636. doi: 10.1038/srep29636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinane A.R., Vilboux T., O’Brien K., Curry J.A., Maynard D.M., Carlson-Donohoe H., Ciccone C., NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Markello T.C., Gunay-Aygun M., Huizing M., Gahl W.A. Homozygosity mapping and whole-exome sequencing to detect SLC45A2 and G6PC3 mutations in a single patient with oculocutaneous albinism and neutropenia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:2017–2025. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale D.C., Person R.E., Bolyard A.A., Aprikyan A.G., Bos C., Bonilla M.A., Boxer L.A., Kannourakis G., Zeidler C., Welte K. Mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase in congenital and cyclic neutropenia. Blood. 2000;96:2317–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels-Wells T.R., Helguera G., Leuchter R.K., Quintero R., Kozman M., Rodríguez J.A., Ortiz-Sánchez E., Martínez-Maza O., Schultes B.C., Nicodemus C.F., Penichet M.L. A novel IgE antibody targeting the prostate-specific antigen as a potential prostate cancer therapy. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasouki M., Saadi I., Ahmed S.O. THPO–MPL pathway and bone marrow failure. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Ther. 2015;8:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplantes C., Fremond M.L., Beaupain B., Harousseau J.L., Buzyn A., Pellier I., Roques G., Morville P., Paillard C., Bruneau J. Clinical spectrum and long-term follow-up of 14 cases with G6PC3 mutations from the French severe congenital neutropenia registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014;9:183. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draber P., Stepanek O., Hrdinka M., Drobek A., Chmatal L., Mala L., Ormsby T., Angelisova P., Horejsi V., Brdicka T. LST1/A is a myeloid leukocyte-specific transmembrane adaptor protein recruiting protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2 to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:28309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.339143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun A., Ozgul R.K., Soydas A., Tugrul T., Gurgey A., Celiker A., Barst R.J., Knowles J.A., Mahesh M., Morse J.H. Familial pulmonary arterial hypertension, leucopenia, and atrial septal defect: a probable new familial syndrome with multisystem involvement. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2009;18:19–23. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32831841f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S.L., Pierre J., Smith-Norowitz T.A., Hagler M., Bowne W., Pincus M.R., Mueller C.M., Zenilman M.E., Bluth M.H. Immunoglobulin E antibodies from pancreatic cancer patients mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008;153:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg V., Kathiriya I.S., Barnes R., Schluterman M.K., King I.N., Butler C.A., Rothrock C.R., Eapen R.S., Hirayama-Yamada K., Joo K. GATA4 mutations cause human congenital heart defects and reveal an interaction with TBX5. Nature. 2003;424:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature01827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Shieh J.-J., Pan C.-J., Chou J.Y. Histidine 167 is the phosphate acceptor in glucose-6-phosphatase-β forming a phosphohistidine enzyme intermediate during catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12479–12483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser C.L., Picoraro J.A., Jain P., Kinberg S., Rustia E., Gross Margolis K., Anyane-Yeboa K., Iglesias A.D., Green N.S. Phenotypic heterogeneity of neutropenia and gastrointestinal illness associated with G6PC3 founder mutation. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016;38(7):e243–e247. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski P., Hesse S., Hollizeck S., Rohlfs M., Behrends U., Sherkat R., Tamary H., Ünal E., Somech R., Patıroğlu T. Proteome analysis of human neutrophil granulocytes from patients with monogenic disease using data-independent acquisition. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2019;18:760–772. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA118.001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayee B., Antonopoulos A., Murphy E.J., Rahman F.Z., Sewell G., Smith B.N., McCartney S., Furman M., Hall G., Bloom S.L. G6PC3 mutations are associated with a major defect of glycosylation: a novel mechanism for neutrophil dysfunction. Glycobiology. 2011;21:914–924. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidemann J., Kebschull M., Tepasse P.R., Bettenworth D. Regulated expression of leukocyte-specific transcript (LST) 1 in human intestinal inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2014;63:513–517. doi: 10.1007/s00011-014-0732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzinger A., Evans T. Gata4 regulates the formation of multiple organs. Development. 2005;132:4005–4014. doi: 10.1242/dev.01978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger I., de Baey A., Messer G., Kick G., Zwierzina H., Weiss E.H. Cloning and genomic characterization of LST1: a new gene in the human TNF region. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:315–322. doi: 10.1007/BF00179392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.-S., Blink S.E., Chin R.K., Lee Y., Kim O., Weinstock J., Waldschmidt T., Conrad D., Chen B., Solway J. Lymphotoxin is required for maintaining physiological levels of serum IgE that minimizes Th1-mediated airway inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1643–1652. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C., Grudzien M., Appaswamy G., Germeshausen M., Sandrock I., Schäffer A.A., Rathinam C., Boztug K., Schwinzer B., Rezaei N. HAX1 deficiency causes autosomal recessive severe congenital neutropenia (Kostmann disease) Nat. Genet. 2006;39:86–92. doi: 10.1038/ng1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillig C.H., Berndt C., Vergnolle O., Lonn M.E., Hudemann C., Bill E., Holmgren A. Characterization of human glutaredoxin 2 as iron-sulfur protein: a possible role as redox sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:8168–8173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.R., Pan C.J., Mansfield B.C., Chou J.Y. Functional analysis of mutations in a severe congenital neutropenia syndrome caused by glucose-6-phosphatase-β deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015;114:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg M., Johansson C., Chandra J., Enoksson M., Jacobsson G., Ljung J., Johansson M., Holmgren A. Cloning and expression of a novel human glutaredoxin (Grx2) with mitochondrial and nuclear isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:26269–26275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwis M.-A., Fillet M., Lutteri L., Marée R., Geurts P., de Seny D., Malaise M., Chapelle J.-P., Wehenkel L., Belaiche J. Proteomics for prediction and characterization of response to infliximab in Crohn’s disease: a pilot study. Clin. Biochem. 2008;41:960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro E.A., Brini A.T., Soprana E., Ambrosi A., Dombrowicz D., Siccardi A.G., Vangelista L. Antitumor IgE adjuvanticity: key role of FcεRI. J. Immunol. 2009;183:4530–4536. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient R.K., McGhee J.D. The GATA family (vertebrates and invertebrates) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:416–422. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00319-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reali E., Greiner J.W., Corti A., Gould H.J., Bottazzoli F., Paganelli G., Schlom J., Siccardi A.G. IgEs targeted on tumor cells: therapeutic activity and potential in the design of tumor vaccines. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5517–5522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustom A., Saffrich R., Markovic I., Walther P., Gerdes H.H. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science. 2004;303:1007–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1093133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabath D.F., Kaushansky K., Broudy V.C. Deletion of the extracellular membrane-distal cytokine receptor homology module of mpl results in constitutive cell growth and loss of thrombopoietin binding. Blood. 1999;94:365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller C., Diakopoulos K.N., Rohwedder I., Kremmer E., von Toerne C., Ueffing M., Weidle U.H., Ohno H., Weiss E.H. LST1 promotes the assembly of a molecular machinery responsible for tunneling nanotube formation. J. Cell Sci. 2012;126:767–777. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simi M., Leardi S., Tebano M.T., Castelli M., Costantini F.M., Speranza V. Raised plasma concentrations of platelet factor 4 (PF4) in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1987;28:336–338. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobhani I., Hochlaf S., Denizot Y., Vissuzaine C., Rene E., Benveniste J., Lewin M.M., Mignon M. Raised concentrations of platelet activating factor in colonic mucosa of Crohn’s disease patients. Gut. 1992;33:1220–1225. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockklausner C., Klotter A.-C., Dickemann N., Kuhlee I.N., Duffert C.M., Kerber C., Gehring N.H., Kulozik A.E. The thrombopoietin receptor P106L mutation functionally separates receptor signaling activity from thrombopoietin homeostasis. Blood. 2015;125:1159–1169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed R.S., Reid S.W., Li C., Cheetham J.C., Aoki K.H., Liu B., Zhan H., Osslund T.D., Chirino A.J., Zhang J. Efficiency of signaling through cytokine receptors depends critically on receptor orientation. Nature. 1998;395:511–516. doi: 10.1038/26773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-da-Cunha M., Chevalier N., Stephenne X., Defour J.-P., Paczia N., Ferster A., Achouri Y., Dewulf J.P., Linster C.L., Bommer G.T., Van Schaftingen E. Failure to eliminate a phosphorylated glucose analog leads to neutropenia in patients with G6PT and G6PC3 deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116:1241–1250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816143116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Veruki M.L., Bukoreshtliev N.V., Hartveit E., Gerdes H.H. Animal cells connected by nanotubes can be electrically coupled through interposed gap-junction channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:17194–17199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins S.C., Salter R.D. Functional connectivity between immune cells mediated by tunneling nanotubules. Immunity. 2005;23:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidle U.H., Rohwedder I., Birzele F., Weiss E.H., Schiller C. LST1: a multifunctional gene encoded in the MHC class III region. Immunobiology. 2018;223:699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Zhang Y.-P., Yu N., Jia Y.-X., Wan S.-J., Wang F.-Y. Serum platelet factor 4 is a reliable activity parameter in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine. 2017;96:e6323. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all data sets/code generated or analyzed during this study.