Abstract

Introduction:

Non-routine events (NRE) are atypical or unusual occurrences in a pre-defined process. Although some NREs in high-risk clinical settings have no adverse effects on patient care, others have the potential to cause serious patient harm. A unified strategy for identifying and describing NREs in these domains will facilitate comparison of results between studies.

Methods:

We conducted a literature search in PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE to identify studies related to NREs in high-risk domains and evaluated the methods used for event observation and description. We applied The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization (JCAHO) taxonomy (cause, impact, domain, type, prevention and mitigation) to the descriptions of NREs from the literature.

Results:

Twenty-five articles that met inclusion criteria were selected for review. Real-time documentation of NREs was more common than retrospective video review. Thirteen studies used domain experts as observers and seven studies validated observations with interrater reliability. Using the JCAHO taxonomy, “cause” was the most common classification method applied, followed by “impact,” “type,” “domain,” and “prevention and mitigation.”

Conclusions:

NREs are frequent in high-risk medical settings. Strengths identified in several studies included the use of multiple observers with domain expertise and validation of the approach of event ascertainment using interrater reliability. By applying the JCAHO taxonomy to the current literature, we provide an example of a structured approach that can be used for future analyses of NREs.

Keywords: clinical safety, healthcare, medical error, structured reviews

INTRODUCTION

A non-routine event (NRE) is any departure from what is expected within a system. In a clinical setting, NREs have been defined as an atypical or unusual occurrence that accounts for any disruption in care.1–5 Before its wider use in medicine, the aviation industry used NRE analysis to identify how teams can address these events and improve performance.6 After adoption in medicine in the early 2000s, NRE analysis has been successfully used to perform similar analyses in a range of clinical settings. Unlike adverse event analysis, NRE analysis is not limited to events leading to poor outcomes, which increases the number of observations and potentially reduces bias.1–3,7 This open-ended approach captures events that are workflow deviations from a pre-defined best practice (e.g., esophageal intubation), unusual events that cause no harm (e.g., provider tripping over wires), or events unrelated to care that create unsafe situations (e.g., power outage).1,3,5 Most of these studies have found that errors directly causing harm are uncommon, but events that are latent safety threats are frequent and could be precursors to adverse events.1,5,8–10 Proper identification and analysis of NREs that represent latent safety threats may facilitate the development of approaches for preventing or mitigating associated harm.

Most recent NRE analyses have been performed in high-risk domains where complex and time-dependent tasks are performed, including the emergency department (ED), operating room (OR), and intensive care unit (ICU).3–5,8,11–13 Within these settings, several approaches for identifying the significance of NREs have been used, including assessment of the associated time expense and harms, and the underlying causes for event occurrence. No standardized terminology has emerged from these analyses, making it difficult to aggregate the results of studies in these settings. Current terms used for NREs includes “potential adverse events,” “disruptions,” “interruptions,” and “near-misses.”1–4,13,14 Although these terms correctly identify NREs, the absence of a unified language has limited comparison of the effects of NREs in different studies. Standardization of NRE terminology and the approaches to identifying NREs will address this challenge, especially when assessing the health burden of NREs.

In this scoping review, we evaluated studies of NREs in high-risk healthcare domains and summarized the strengths and weaknesses of the methods used to assess NREs. We applied the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) patient safety event taxonomy to the NREs as an example of a classification method that can be used to clarify language describing these events.15 We contribute to the patient safety literature by (1) showing the utility of a taxonomy for analyzing NREs, and (2) providing an approach for making comparisons between the findings of existing and future studies.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We identified index articles classifying NREs in high-risk patient care settings to initiate the development of search terms.5,14,16,17 We defined the search using MESH terms from these articles, limiting inclusion to those with non-routine events or similar language in the title or abstract, and to those occurring in high-risk domains such as the ED, OR, or ICU settings. We focused on these healthcare settings because of the complexity and time-sensitivity of associated management and treatment decisions in these domains. To ensure the identification of articles using any term similar to “non-routine,” we also included words such as “atypical” and “unexpected” in the search (see Appendix 1). In December 2018, we searched three databases (PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE) for relevant studies, limiting the results to articles published after 2007 and in English. A separate search was performed with key terms using Google and Google Scholar. Following the de-duplication of sources, the primary author conducted a title screen to eliminate irrelevant articles, identifying titles with phrases such as “atypical presentation” and “a rare case report.” We used the Covidence systematic review management system for reference management and screening at the abstract level.18 Our study was registered as a scoping review with the Center for Open Science.19

Three reviewers evaluated the abstracts using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria required that the study evaluated NREs or events similar to NREs, such as potential adverse events, near-misses, interruptions, and disturbances. The studies were included if performed in a high-risk setting with a methodology involving video review or real-time observation of events. The latter requirement limited the search to articles with objective ascertainment of events, a feature absent from articles relying only on voluntary reporting. We only included articles that described features of the events so we could perform a post hoc classification of the events.

During the abstract review stage, we excluded studies fitting the following criteria: performance in a low-risk setting, case reports, inclusion of events only related to medication administration or another single category of team action, retrospective database reviews, or use of voluntary reporting instead of direct observation or retrospective video review. We excluded papers that only included a single category of team action because their inclusion would limit comparison to other papers that attempted to identify all types of events.

Data Extraction

After reaching a consensus on studies for the next stage of review, three reviewers independently extracted data from the articles (Appendix 2). Extracted data from each study included the clinical setting, number of observers used to determine NREs, level of training or profession of these observers, method of case review (e.g., video or real-time observation), number of cases analyzed, number of NREs identified, and method used to classify NREs (Table 1). To evaluate the classification methods of NREs, two reviewers independently used the JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy to assign one or more classifications (impact, type, domain, cause, and prevention and mitigation) to the events described by each study.15 “Impact” classification was assigned to articles that assessed outcomes or effects of the NREs, typically reported as harm to the patient or delay in care.5,12,14,16,20–31 “Type” classification was assigned to articles that classified NREs by the underlying mechanism by which the event was affected, such as communication or teamwork, or by a specific error type, such as omission or commission.5,8,12,14,16,17,20,21,23,28,32–34 The “domain” of the articles included in the review was pre-determined at the time of article selection as “high-risk” but was further defined when the analysis was restricted to specific parts or phases of the setting in which the NREs occurred.5,8,13,22,28,30,35,36 “Cause” classification was assigned to articles that identified and reported contributing factors or agents (e.g., patient or practitioner) that led to NREs.5,8,12,14,16,17,21–31,33–35,36 Finally, the “prevention and mitigation” classification was assigned to the articles that evaluated measures (e.g., checklists) to reduce NREs.8,14,29,36

Table 1.

Classification Method of Studies Evaluating Non-routine Events in High-Acuity Settings

| Authors | Method | Case Type | Case Specialty | Sample Size/Type | JCAHOa Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healey, AN et al. (2007)20 | real-time | operative | urology | 30 cases | impact, type |

| Wiegmann DA, et al. (2007)21 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery | 31 cases | impact, type, cause |

| Barach, P, et al. (2008)22 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery, general surgery |

102 cases | impact, domain, cause |

| Burtscher, MJ, et al. (2010)8 | video | operative | anesthesiology | 22 cases | type, domain, cause, prevention/mitigation |

| Gelbart, B, et al. (2010)35 | video | critical care | obstetrics, neonatology |

20 cases | domain, cause |

| McGillis Hall, L, et al. (2010)23 | real-time | critical care | pediatrics | 384 hours | impact, type, cause |

| Parker, SE, et al. (2010)24 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery | 12 cases | impact, domain, cause |

| Savoldelli, GL, et al. (2010)25 | video | operative | anesthesiology | 37 cases | impact, cause |

| Williams, AL, et al. (2010)32 | video | critical care | neonatology | 12 cases | type, domain |

| Forster, AJ, et al. (2011)26 | real-time | operative, critical care |

cardiac surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics |

1406 patients | impact, cause |

| Kahol, K, et al. (2011)16 | real-time | trauma | trauma | 10 cases | impact, type, cause |

| Pereira, BMT, et al. (2011)37 | real-time | operative | trauma surgery | 50 cases | cause |

| Schraagen, JM, et al. (2011)12 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery | 40 cases | impact, type, cause |

| Campbell, G, et al. (2012)27 | real-time | operative | anesthesiology | 30 cases | impact, cause |

| Hu, YY, et al. (2012)14 | video | operative | general surgery, surgical oncology |

10 cases | impact, type, cause, prevention/mitigation |

| Bellora, E, et al. (2013)36 | real-time | operative | general surgery, orthopedic surgery |

61 cases | domain, prevention/mitigation |

| Dedhia, RC, et al. (2013)28 | real-time | operative | otolaryngology | 23 cases | impact, type, domain, cause |

| Yamada, NK, et al. (2015)17 | video | critical care | neonatology | 23 cases | type, cause |

| Raman, J, et al. (2016)29 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery | 380 cases | impact, cause, prevention/mitigation |

| Webman, RB, et al. (2016)5 | video | trauma | trauma | 39 cases | impact, type, domain, cause |

| Blikkendaal, MD, et al. (2017)30 | video | operative | gynecology | 40 cases | impact, domain, cause |

| Cohen, TN, et al. (2017)33 | real-time | operative | cardiac surgery | study I- 15 cases study II- 25 cases |

type, cause |

| Slagle, JM, et al. (2018)13 | video | operative | anesthesiology | 319 cases | type, domain |

| Hamilton, EC, et al. (2018)34 | real-time | operative | pediatric surgery | 211 cases | type, cause |

| Law, KE, et al. (2018)31 | real-time | operative | gynecology | 45 cases | impact, cause |

JCAHO- joint commission on accreditation of healthcare organizations

RESULTS

Search Results

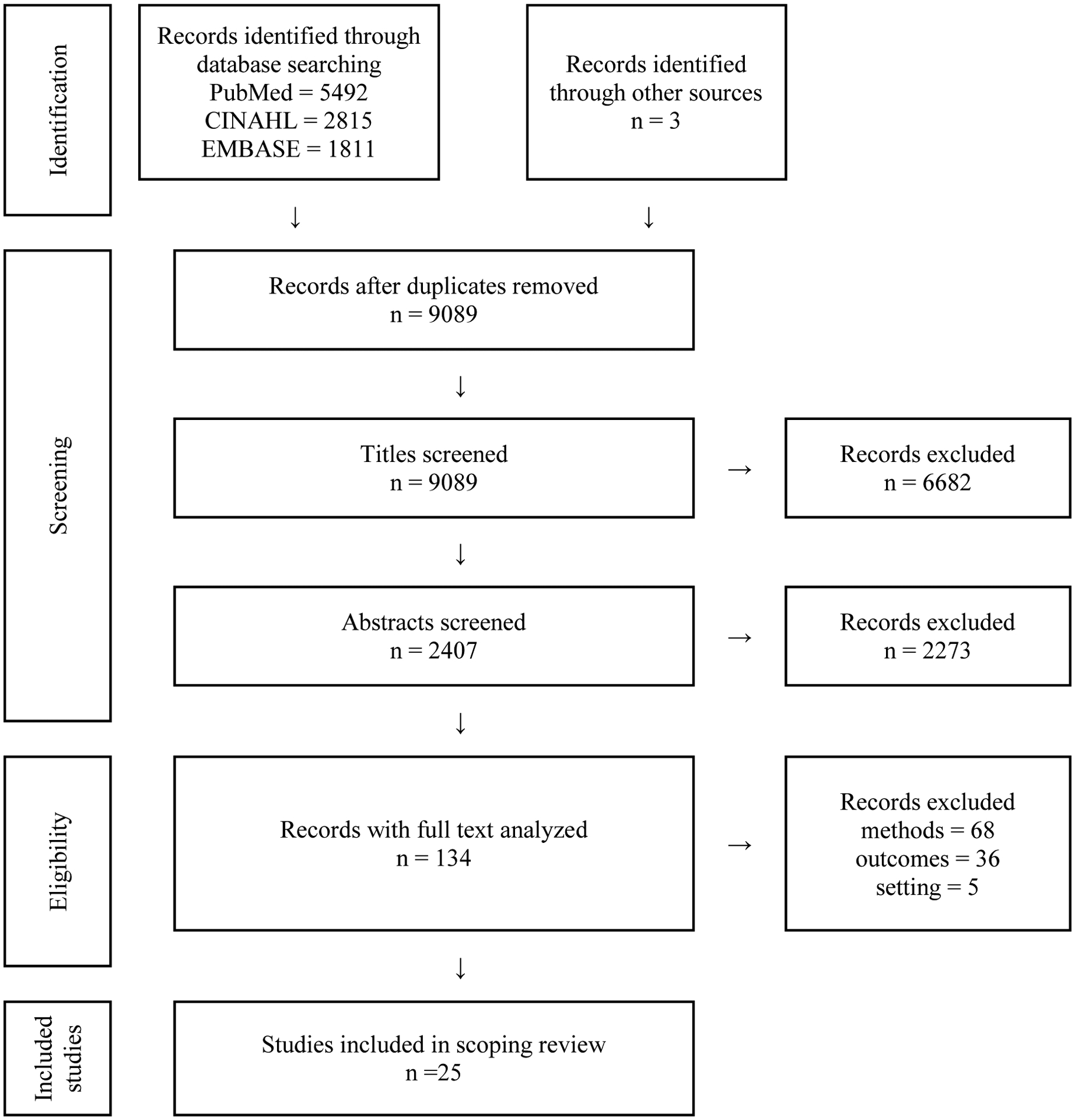

The initial search yielded 9,089 articles after de-duplication. Following a title screen to eliminate irrelevant articles and case reports, 2,407 articles underwent abstract review, and 134 underwent full-text review. Among those undergoing full review, 68 were excluded due to methodology (e.g., retrospective chart review, database study), 36 due to no description of NREs (e.g., focus on medication errors, leadership behaviors), and five due to the setting (e.g., general medical ward, outpatient clinic) (Figure 1). We included 25 full-text articles meeting inclusion criteria in the final review (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram Showing Selection of Articles for Review

Description of Included Studies

Sixteen studies used real-time, in-person prospective surveillance of events, while the other nine studies used retrospective video review. Five studies used the term “NRE” to describe events, while the others used language such as “potential adverse events,” “distractions,” and “interruptions” to describe NREs.5,8,12,13,31 The most common setting was the OR (n=19), followed by the ICU (n=5). One study included observations of adverse and potential adverse events in both the OR and ICU.26 Two papers included an analysis of NREs occurring in the setting of trauma resuscitation in the ED.5,16 Studies that focused on NREs in the OR included procedures performed in a range of specialty areas, including urology (n=1), cardiac surgery (n=7), general surgery (n=3), trauma surgery (n=1), surgical oncology (n=1), orthopedic surgery (n=1), otolaryngology (n=1), gynecology (n=2), and pediatric surgery (n=1).12,14,20–22,24,26,28–31,33,34,36,37 Four papers with a focus on NREs in the OR included only those related to anesthesiology providers.8,13,25,27

Twenty-four studies included information about the observers documenting the NREs. In 13 studies, observers had a medical background, including nurses, medical students, residents, fellows, or attending physicians who were familiar with or worked in the setting.5,8,13,14,20,21,24,25,27,28,32,34,,35 Four studies included only observers without medical experience.12,23,31,33 Fourteen studies included more than one observer.5,14,22–25,28,30–35,37 Interrater reliability testing was reported in seven studies.23,24,30–,34

Among the 18 studies conducted only in an OR setting, a range of 10 to 380 cases were observed per study (median=40 cases).8,12–14,20–22,24,25,27–31,33,34,36,37 One study included NREs occurring in both the OR and ICU over an aggregate observation period of 1,406 hours.26 In studies performed in an ICU setting, one included an evaluation of 384 hours of observations in a pediatric critical care setting, while three studies included an analysis of NREs occurring during medical resuscitation (range 12–250 resuscitations).17,23,32,35 Two studies included an analysis of NREs occurring during trauma resuscitation (range 10–39 resuscitations).5,16 Although NREs were observed in all studies, not every case or patient-hour had an NRE. The findings of each study showed that NREs are common but there was a wide variation in the number of NREs identified per case. The frequency of NREs per case in the included studies ranged from 30 NREs occurring in 380 cases (average 0.08 NREs per case) to 4,233 NREs in 25 cases (average 169.3 NREs per case).29,33

Distribution of JCAHO Taxonomy Classifications among Included Studies15

Twenty-one studies included a classification of NREs by “cause,” attributing events to internal and external systems failures, and identifying components such as equipment availability, patient disease, and the provider associated with the NRE. The provider roles were pre-defined based on who was expected to be present in each clinical setting.5,8,12,14,16,17,21–31,33–35,37 Fourteen studies included a “type” classification of the involved process causing the NRE or classified based on an overarching theme.5,13,16,17,23,28,34 In studies that classified NREs by “type,” NREs were frequently attributed to failures in team communication or patient management.5,8,12,14,20,21,28,32,33

Sixteen studies reported NREs by “impact” by assessing the time expense of the NRE or the potential for harm. Studies that included an analysis of the time cost of NREs used scales ranging from no temporal disruption to full case cessation.14,20,21,28–31 Studies that classified NREs based on the potential for harm included several definitions of harm categories, including minor/major, no harm/harm, and positive/negative.5,16,22,23,25–27 A common conclusion was that events propagating to a harmful outcome were rare, but mitigated events that could cause harm were common.12,22,24,26

The “domain” category encompasses the settings in which events occur and was selected for by our inclusion criteria of “high-risk” clinical settings. Ten studies created more narrow domains by classifying NREs based on the phase of the event in which each occurred. The studies of NREs in the OR reported the occurrence of NREs in distinct periods such as “medication phase” and “intubation phase” or “induction,” “maintenance,” and “emergence.”8,13,22,24,28,30,36 Studies conducted in the ICU or in a trauma resuscitation setting included analyses within phases defined by the protocols used in these domains, e.g., Pediatric Advanced Life Support and Advanced Trauma Life Support.5,32,35 Four studies that used “prevention and mitigation” included an assessment of the utility of a checklist or reporting system as a method for preventing the occurrence of NREs. “Prevention and mitigation” was also classified by the type of compensatory method used to mitigate the impact of NREs.8,14,29,36

Most studies (n=24) included NRE analysis that involved more than one JCAHO classification method.15 Although no study used all five JCAHO patient safety classifications, four studies used four classes: one study included analysis by type, domain, cause, and prevention and mitigation; one by impact, type, cause, and prevention and mitigation; and two by impact, type, domain, and cause (Appendix 2).5,8,14,28

DISCUSSION

This scoping review presents the findings of the medical NRE analyses performed in high-risk clinical domains over the past decade. Because of the diversity of settings, differences in the patient care processes, and different terminology used in each study, comparison of NREs and their features between studies is difficult. The development of a unified definition of NREs and their classifications will facilitate this type of comparison and allow for NRE analyses in aggregate across clinical domains. The main purpose of this review was to determine the optimal approach for NRE ascertainment and description that would aid in assessment of the burden of NREs on healthcare. We applied the JCAHO patient safety taxonomy to describing these events, an accepted nomenclature that has been used in studies of adverse events and patient safety.38–40 A benefit of the JCAHO taxonomy is that outlined classifications are interrelated. For example, the “domain” creates an environment in which “causes” can lead to different “types” of NREs that have varying “impacts” and require different strategies for “prevention and mitigation.” We propose that this or a similar method of classifying NREs is needed when evaluating NREs in high-risk medical settings. The use of the common language from the JCAHO taxonomy will enable a future meta-analysis of the overall burden of NREs in these settings.15

Structuring an NRE Analysis

The studies included in the review used several methods for analyzing NREs. A combination of methods from different studies could yield the optimal NRE assessment approach. Real-time, in-person observation is known to cause behavior and practice alterations (i.e., Hawthorne effect) because providers know they are being observed.13,14,25,28–31 Analysis of video recordings is an alternative that allows for repeated reviews from multiple angles.30,35 Video review may reduce the potential for a Hawthorne effect when compared to in-person observation.13,14,25,28–31,41,42 Despite the potential advantages of video review, this method may not be an option because of the associated costs of recording systems, the legal implications of recording patient care, or the use of a fixed camera position limiting a complete view of the clinical scene.8,17,30,35,43 Few studies that have directly compared these two methods of review have been performed in simulation and not in actual clinical practice.44,45 Both video review and real-time observation can be considered appropriate methods for evaluating NREs until direct comparison has been performed in practice.

Understanding the clinical contexts associated with NREs reduces the risk of misinterpreting why an event occurred when using only retrospective case review.46 Because voluntary reporting systems may lead to underreporting of NREs due to lack of incentive to report all events, we excluded studies if direct observation was not used.2,3,47 Studies that use a combination of voluntary reporting and facilitated surveys have identified workflow deviations that can lead to patient harms but retain the bias of self-report.3,4 Direct observation supplemented by voluntary reporting, facilitated interview, and chart review may improve NRE ascertainment and should be considered in future studies. The use of other modes of NRE reporting will increase the validity of NRE review.

The use of observers with medical expertise to identify NREs was included in only 13 studies. Observers with domain experience may identify nuances that would not be noticeable to others. Expert review, however, may be associated with the higher cost and may not be feasible in specialized domains where the availability of individuals for performing these time-consuming studies is limited.5,32 The familiarity of experts with the clinical setting also may lead to bias and loss of objectivity. The bias can be mitigated with the use of multiple observers and the measurement of interrater reliability, a method used in several studies.23,24,30–34 The use of multiple observers and assessment of interrater reliability should be included to support reproducibility.

NREs as Safety Concerns

Studies in this scoping review showed that NREs are frequent in high-risk medical settings, but the difference in NRE language lead to a wide variation in the number of NREs identified in each study. A common conclusion was that the identified NREs have potential impacts on patient safety, care delivery, and overall outcomes. Although most NREs did not cause direct patient harm, NREs were considered precursor events or latent safety threats in each study. From this perspective, understanding the factors that contribute to NREs will aid in the development of strategies for mitigating or preventing patient harm.5,8,13,21,23,24,26,31,32 The underlying cause of NREs was often multifactorial, relating to the involved providers, the clinical status of the patient, or the complexity of the patient care task.5,12–14,16,17,20–,22,25,27,28,30,31,33,37 To address provider-related factors related to NREs, several strategies have been proposed to improve teamwork and communication, such as perioperative briefings, closed-loop communication, effective decision making, and increased information sharing.8,12,14,21,28,31,32 Other systems, such as revisions to pre-existing hospital protocols, can address problems originating external to the team that create preconditions for unsafe acts. Adjuncts such as checklists and timeout pauses also have been suggested and successfully used as interventions to reduce NREs and adverse outcomes.5,8,17,29,36

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The search strategy included three relevant databases but had a year restriction placed on publications. Although the practice of NRE identification is not novel, the application of NRE classifications in healthcare has been a relatively new focus, supporting this restriction.1,6 Only publications in English were reviewed. Additional reports of studies in other languages may exist that were not included. Although we included generic terms in our search, our search may have missed papers because of the lack of standardized terminology for describing NREs. Our review highlighted the importance of standardizing terminology for future reviews to address this limitation. Although we identified common themes and proposed future areas of study, our review included only 25 papers. Because of the limited number of available studies, we were only able to aggregate studies at a high-level. As more work is published in this area, additional insights into the optimal approach for ascertaining, classifying, and establishing the relevance of NREs will emerge.

Conclusions

Our review of studies addressing NREs in high-risk medical settings shows that NREs are common but rarely contribute directly to patient harm. The authors of several studies have proposed that NREs may represent latent safety threats to patients. A comparison of the results of studies of NREs will be facilitated by the use of shared definitions and classifications. Our proposed use of the taxonomy outlined by JCAHO may allow an aggregate analysis of the health burden of NREs in high-risk domains.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health award R01LM011834.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All authors made significant contributions to the enclosed work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinger MB, Slagle J. Human factors research in anesthesia patient safety: techniques to elucidate factors affecting clinical task performance and decision making. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:756–760. DOI: 10.1197/jamia.M1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinger MB, Slagle J, Jain S, Ordonez N. Retrospective data collection and analytical techniques for patient safety studies. J Biomed Inform. 2003;36(1–2):106–119. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oken A, Rasmussen MD, Slagle JM, et al. A facilitated survey instrument captures significantly more anesthesia events than does traditional voluntary event reporting. Anesthesiology. 2007;107(6):909–922. DOI: 10.1097/01.anes.0000291440.08068.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matte GS, Riley D, LaPierre R, et al. The Children’s Hospital Boston non-routine event reporting program. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2010;42(2):58–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webman R, Fritzeen J, Yang J, et al. Classification and team response to non-routine events occurring during pediatric trauma resuscitation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(4):666–673. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waller MJ. The timing of adaptive group responses to nonroutine events. Acad Manag J. 1999;42(2):127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henricksen K, Kaplan H. Hindsight bias, outcome knowledge and adaptive learning. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(2):ii46–50. DOI: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burtscher MJ, Wacker J, Grote G, Manser T. Managing nonroutine events in anesthesia: the role of adaptive coordination. Hum Factors. 2010;52(2):282–294. DOI: 10.1177/0018720809359178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yorio PL, Moore SM. Examining factors that influence the existence of Heinrich’s safety triangle using site-specific H&S data from more than 25,000 establishments. Risk Anal. 2018;38(4):839–852. DOI: 10.1111/risa.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis NJ, Dennison G, Brown CSB, et al. Clinical evaluation of intraoperative near misses in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henrickson Parker S, Schmutz JB, Manser T. Training needs for adaptive coordination: utilizing task analysis to identify coordination requirements in three different clinical settings. Group Organ Manag. 2018;43(3):504–527. DOI: 10.1177/1059601118768022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schraagen JM, Schouten T, Smit M, et al. A prospective study of paediatric cardiac surgical microsystems: assessing the relationships between non-routine events, teamwork and patient outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:599–603. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slagle JM, Porterfield ES, Lorinc AN, et al. Prevalence of potentially distracting noncare activities and their effects on vigilance, workload, and nonroutine events during anesthesia care. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(1):44–54. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu YY, Arriaga AF, Roth EM, et al. Protecting patients from an unsafe system: the etiology and recovery of intraoperative deviations in care. Ann Surg. 2012;256(2):203–210. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182602564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang A, Schyve PM, Croteau RJ, et al. The JCAHO patient safety event taxonomy: a standard terminology and classification schema for near misses and adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(2):95–105. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahol K, Vankipuram M, Patel VL, Smith ML. Deviations from protocol in a complex trauma environment: errors or innovations? J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(3):425–431. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada NK, Yaeger KA, Halamek LP. Analysis and classification of errors made by teams during neonatal resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2015;96:109–113. DOI: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation; Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. [Google Scholar]

- 19.[Blinded authors]. (2019, December 18). A Scoping Review of Non-routine Events in High Acuity Settings. Retrieved from osf.io/e3jtv.

- 20.Healey AN, Primus CP, Koutantji M. Quantifying distraction and interruption in urological surgery. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:135–139. DOI: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiegmann DA, ElBardissi AW, Dearani JA, et al. Disruptions in surgical flow and their relationship to surgical errors: an exploratory investigation. Surgery. 2007;142(5):658–665. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barach P, Johnson JK, Ahmad A, et al. A prospective observational study of human factors, adverse events, and patient outcomes in surgery for pediatric cardiac disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136(6):1422–1428. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGillis Hall L, Penderson C, Hubley P, et al. Interruptions and pediatric patient safety. J Pediatr Nurs. 2010;25(3):167–175. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker SHE, Laviana AA, Wadhera RK, et al. Development and evaluation of an observational tool for assessing surgical flow disruptions and their impact on surgical performance. World J Surg. 2010;34(2):353–361. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-009-0312-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savoldelli GL, Thieblemont J, Clergue F, et al. Incidence and impact of distracting events during induction of general anesthesia for urgent surgical cases. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010:27(8):683–689. DOI: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328333de09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster AJ, Worthington JR, Hawken S, et al. Using prospective clinical surveillance to identify adverse events in hospital. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:756–763. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell G, Arfanis K, Smith AF. Distraction and interruption in anesthetic practice. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109(5):707–715. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aes219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dedhia RJ, Shwaish K, Snyderman CH, et al. Perioperative process errors and delays in otolaryngology at a veteran’s hospital: prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(12):3010–3015. DOI: 10.1002/lary.24191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raman J, Leveson N, Samost AL, et al. When a checklist is not enough: how to improve them and what else is needed. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):585–592. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blikkendaal MD, Driessen SRC, Rodirgues SP, et al. Surgical flow disturbances in dedicated minimally invasive surgery suites: an observational study to assess its supposed superiority over conventional suites. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(1):288–298. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-016-4971-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law KE, Hildebrand EA, Hawthorne HJ, et al. A pilot study of non-routine events in gynecological surgery: type, impact, and effect. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(2):298–303. [Epub ahead of print 2018, Dec 6]. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams AL, Lasky RE, Dannemiller JL, et al. Teamwork behaviors and errors during neonatal resuscitation. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:60–64. DOI: 10.1136/qshc.2007.025320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen TN, Wiegmann DA, Reves ST, et al. Coding human factors observations in surgery. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(5):556–562. DOI: 10.1177/1062860616675230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton EC, Pham DH, Minzenmayer AN, et al. Are we missing the near misses in the OR? Underreporting of safety incidents in pediatric surgery. J Surg Res. 2018;221:336–342. DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelbart B, Hiscock R, Barfield C. Assessment of neonatal resuscitation performance using video recording in a perinatal centre. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46(7–8):378–383. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellora E, Falzoni M. Surgery checklist implementation to reduce clinical risk in the pediatric operating room. Minerva Pediatr. 2013;65(6):617–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira BM, Pereira AM, Correia CdosS, et al. Interruptions and distractions in the trauma operating room: understanding the threat of human error. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2011;38(5):292–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mriza SK, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, et al. Towards standardized measurement of adverse events in spine surgery: conceptual model and pilot evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;20(7):53. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Runciman W, Hibbert P, Thompson R, et al. Towards an international classification for patient safety: key concepts and terms. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(1):18–26. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee W, Zhang E, Chiang C, et al. Comparing the outcomes of reporting and trigger tool methods to capture adverse events in the emergency department. J Patient Saf. 2019;15(1):61–68. DOI: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sedgwick P, Greenwood N. Understanding the Hawthorne effect. BMJ. 2015;351:h4672. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rea J, Stephenson C, Leasure E, et al. Perceptions of scheduled vs. unscheduled directly observed visits in an internal medicine residency outpatient clinic. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):64. DOI: 10.1186/s12909-020-1968-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNicholas AR, Reilly EF. The role of trauma video review in optimizing patient care. J Trauma Nurs. 2018;25(5):307–310. DOI: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.House JB, Dooley-Hash S, Kowalenko T, et al. Prospective comparison of live evaluation and video review in the evaluation of operator performance in a pediatric emergency airway simulation. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):312–316. DOI: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00123.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams JB, McDonough MA, Hillard MW, et al. Intermethod reliability of real-time versus delayed videotaped evaluation of a high-fidelity medical simulation septic shock scenario. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(9):887–893. DOI: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinger MB, Herndon OW, Zornow MH, et al. An objective methodology for task analysis and workload assessment in anesthesia providers. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:77–92. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palermo D, DiPaolo ER, Stadelmann C, et al. Incident reports versus direct observation to identify medication errors and risk factors in hospitalized newborns. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2018;178:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.