Abstract

Objective

To examine the trends in obesity and adiposity measures, including body mass index, waist circumference, body fat percentage, and lean mass, by race or ethnicity among adults in the United States from 2011 to 2018.

Design

Population based study.

Setting

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2011-18.

Participants

A nationally representative sample of US adults aged 20 years or older.

Main outcome measures

Weight, height, and waist circumference among adults aged 20 years or older were measured by trained technicians using standardized protocols. Obesity was defined as body mass index of 30 or higher for non-Asians and 27.5 or higher for Asians. Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference of 102 cm or larger for men and 88 cm or larger for women. Body fat percentage and lean mass were measured among adults aged 20-59 years by using dual energy x ray absorptiometry.

Results

This study included 21 399 adults from NHANES 2011-18. Body mass index was measured for 21 093 adults, waist circumference for 20 080 adults, and body fat percentage for 10 864 adults. For the overall population, age adjusted prevalence of general obesity increased from 35.4% (95% confidence interval 32.5% to 38.3%) in 2011-12 to 43.4% (39.8% to 47.0%) in 2017-18 (P for trend<0.001), and age adjusted prevalence of abdominal obesity increased from 54.5% (51.2% to 57.8%) in 2011-12 to 59.1% (55.6% to 62.7%) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.02). Age adjusted mean body mass index increased from 28.7 (28.2 to 29.1) in 2011-12 to 29.8 (29.2 to 30.4) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.001), and age adjusted mean waist circumference increased from 98.4 cm (97.4 to 99.5 cm) in 2011-12 to 100.5 cm (98.9 to 102.1 cm) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.01). Significant increases were observed in body mass index and waist circumference among the Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic Asian groups (all P for trend<0.05), but not for the non-Hispanic black group. For body fat percentage, a significant increase was observed among non-Hispanic Asians (30.6%, 29.8% to 31.4% in 2011-12; 32.7%, 32.0% to 33.4% in 2017-18; P for trend=0.001), but not among other racial or ethnic groups. The age adjusted mean lean mass decreased in the non-Hispanic black group and increased in the non-Hispanic Asian group, but no statistically significant changes were found in other racial or ethnic groups.

Conclusions

Among US adults, an increasing trend was found in obesity and adiposity measures from 2011 to 2018, although disparities exist among racial or ethnic groups.

Introduction

Obesity is recognized as a common, complex, serious, and costly disease, and continues to be a major focus of public health efforts worldwide. Obesity has broad effects on human health, being associated with increased risk of physical diseases (eg, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease)1 and mental illnesses (eg, depression, substance abuse, and schizophrenia),2 and also results in increased mortality.3 4 Obesity has caused sizable burdens to people, communities, and society.5 Therefore, it is crucial to track the prevalence of obesity to provide evidence to inform policy efforts and prevention programmes.

Accurate assessment of adiposity is important for obesity research, practice, and policy.6 Body mass index is the most widely used index of obesity, but it cannot accurately reflect body adiposity.6 7 Waist circumference is a good measure of abdominal fatness, and is used to define central obesity and metabolic syndrome.8 Imaging based methods for assessing body composition have been increasingly used as an objective measure of adiposity. Among imaging based methods, dual energy x ray absorptiometry is a validated method for body composition assessment.

In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has been the leading source to track trends in obesity among US adults since the 1980s.9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 However, previous studies that have reported trends in obesity usually assessed obesity by body mass index9 10 11 12 13 14 15 and waist circumference16 17 18 19; although these measures are useful, they cannot directly assess body fat or adiposity. Data on recent national trends in adiposity measured by body fat percentage are lacking in the US. In NHANES cycles from 2011-12 to 2017-18, whole body dual energy x ray absorptiometry scans were administered, which provided a unique opportunity to assess the recent trends in obesity, adiposity, and lean mass measures among the general population in the US.20 21

The 2011-18 NHANES cycles oversampled non-Hispanic Asians in addition to traditionally oversampled groups, including people of Hispanic and non-Hispanic black race or ethnicity.22 Before the 2011-12 NHANES cycle, non-Hispanic Asians were not differentiated in the released data and were included as a whole in the ‘other’ racial or ethnic category. In the US, there were 18.3 million Asian Americans in 2017, accounting for 5.7% of the nation’s population, and this proportion is projected to grow to 36.8 million (9.1%) in 2060.23 Given the continuous growth of the Asian American population, an urgent need exists to understand health conditions and risk factors among this group. Asians are known to have a different body composition than other racial or ethnic groups. The World Health Organization24 and the American Diabetes Association25 have recommended lower cut-off points for body mass index in the Asian population than the general population to define obesity (≥27.5 and ≥30, respectively). Moreover, the specific body mass index cut-off points for the Asian population have been recommended by the American Diabetes Association to define and classify obesity among Asian Americans in the 2016 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.26 At a given body mass index, Asians tend to have higher risks of certain diseases such as diabetes than people of other races or ethnicities.24 25

We need to address the critical data gap relating to the national prevalence and trends in obesity among Asian Americans compared with other racial or ethnic groups. In this study, we used data from NHANES 2011-18 to examine national trends in obesity and adiposity measures, including body mass index, waist circumference, body fat percentage, and lean mass, by race or ethnicity among US adults.

Methods

NHANES is a nationally representative survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, a unit of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To represent the civilian non-institutionalized US population, NHANES applied a complex, multistage probability sampling design and recruited approximately 10 000 participants in each two year cycle.27 NHANES data comprise a combination of in-person interviews and physical examinations that cover general health, disease history, health behavior, physiological measures, and diet and nutritional status.27 Starting in 2011, NHANES restarted performing whole body dual energy x ray absorptiometry scans to provide data on body composition, and oversampled non-Hispanic Asians to increase statistics precision for this racial group.28 In recent years, the response rate to national surveys has gradually decreased from 66% in 2011-12 to 47.7% in 2017-18. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has further evaluated the data and conducted enhanced weighting adjustment to minimize potential nonresponse bias.29 Detailed descriptions of NHANES methods and data access are publicly available on the NHANES website.30 NHANES procedures were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board.31 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

In this study, we used data from NHANES 2011-12 to 2017-18. Among the 21 646 adults who participated in NHANES 2011-18, pregnant women were excluded from the current analyses (n=247). Additionally, anthropometric measurement data were missing for body mass index (n=306) and waist circumference (n=1319). Dual energy x ray absorptiometry was only conducted among adults aged 20-59 years (n=14 100), among which data on body composition were missing for 3236 adults for various reasons (appendix fig 1). Ultimately, we obtained data on body mass index for 21 093 adults, on waist circumference for 20 080 adults, and on body composition for 10 864 adults aged 20-59 years. Appendix figure 1 shows a flowchart of participants.

Body measures

Trained staff used standardized techniques to measure weight, height, and waist circumference for all adults aged 20 years or older.32 Participants were weighed in mobile examination centers, wearing only underclothing and an examination gown; weight was recorded on a digital scale in kilograms. Standing height was measured using a stadiometer with a fixed vertical backboard and an adjustable headpiece. Waist circumference was measured just above the iliac crest using a steel measuring tape. The NHANES anthropometry procedures manual provides detailed descriptions of the measurement protocol, equipment, and quality control.32 Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by squared height in meters. General obesity was defined as body mass index of 27.5 or higher for Asians and 30 or higher for non-Asians (people of Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other race or ethnicity categories). Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference of at least 102 cm for men and at least 88 cm for women.

Body composition (body fat percentage and lean mass, excluding bone mass) was measured for adults aged 20-59 years by using dual energy x ray absorptiometry, which was performed by trained and certified radiology technologists who followed a standard protocol.33 Whole body scans, with an extremely low radiation exposure (<20 μSv), were performed on Hologic QDR 4500A fan beam bone densitometers, and the data were analyzed with Hologic APEX version 4.0 software with the NHANES BCA option.

Other variables

Information about age, sex, and race or ethnicity was collected using standardized questionnaires during in-person interviews. All NHANES questionnaires had two versions: English and Spanish. An interpreter helped non-English or non-Spanish speakers, or those who did not speak enough English, during in-person interviews.

Data collection and reporting of race or ethnicity were in accordance with the 1997 US Office of Management and Budget standards. Participants were first asked whether they were of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish ancestry. Participants were then asked about their race; categories were American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, black or African American, Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander, white, and other. Multiple selections were acceptable. In NHANES 2011-18, race or ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic (Mexican and non-Mexican Hispanic), non-Hispanic Asian, and other race or ethnicity. Hispanics, regardless of their race, single or multiple, were categorized as Hispanic. Non-Hispanic participants who indicated they were black or white were recoded into the respective categories. The non-Hispanic Asian category included all people with origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, South East Asia, or the Indian subcontinent (for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam). The other race category included those who reported a race other than black, white, or Asian, or those who reported more than one race.34

Data analysis

According to the NHANES analytic guidelines, we accounted for examination sample weights to obtain variance estimates in the data given the use of a stratified multistage probability design in NHANES.28 34 Because the prevalence of obesity varies across ages and to be comparable with previous reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,11 age adjusted estimates were calculated using the 2000 census data and based on recommendations from NHANES.35 In 2000, the proportion of adults aged 20-39 years, 40-59 years, and 60 years or older was 0.3966, 0.3718, and 0.2316, respectively.36 A different proportion (0.5161 for 20-39 years and 0.4839 for 40-59 years) was used for the analyses of body fat percentage and lean mass because these measures were only determined in adults aged 20-59 years. As a sensitivity analysis, we also calculated the unadjusted values and trends.

We calculated age adjusted mean body mass index, mean waist circumference, mean body fat percentage, and mean lean mass. Additionally, we calculated age adjusted prevalence of general obesity and abdominal obesity, overall and stratified by race or ethnicity and sex, for each cycle from 2011-12 to 2017-18. To investigate linear trends over time, we performed multivariable linear regressions (for body mass index, waist circumference, body fat percentage, and lean mass) or logistic regressions (obesity and abdominal obesity) with survey cycles as a continuous independent variable in models. Age, race or ethnicity, and sex were adjusted in those models except when used as a stratified variable. To be comparable with previous reports on obesity defined by body mass index, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis using the cut-off point for the general population (≥30) to define obesity in non-Hispanic Asians. Additionally, to be comparable with the study population for body fat percentage and lean mass, we provided results for age adjusted mean body mass index and waist circumference, and the age adjusted prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity among adults aged 20-59 years in sensitivity analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using survey modules of SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

Participants were not involved in the development of the research question or the outcome measures, or in the design or implementation of the study. No participants were asked to advise on interpretation or writing of the manuscript. All the data are deidentified.

Results

In this study, we had different sample sizes for various measures: 21 093 for body mass index, 20 080 for waist circumference, and 10 864 for body fat percentage and lean mass. In the main study sample, the weighted mean age was 47.9 years (standard error 0.3); 10 794 participants were women (weighted proportion 51.4%); 7757 were of non-Hispanic white ancestry (weighted proportion 64.8%), 5037 were of Hispanic ancestry (weighted proportion 14.9%), 4809 were of non-Hispanic black ancestry (weighted proportion 11.3%), and 2732 were of non-Hispanic Asian ancestry (weighted proportion 5.6%). Sample sizes and population characteristics varied slightly across survey cycles (appendix table 1). Appendix table 2 shows unweighted sample sizes for adults 20 years and older by sex, age, and race or ethnicity in NHANES 2017-18.

Body mass index

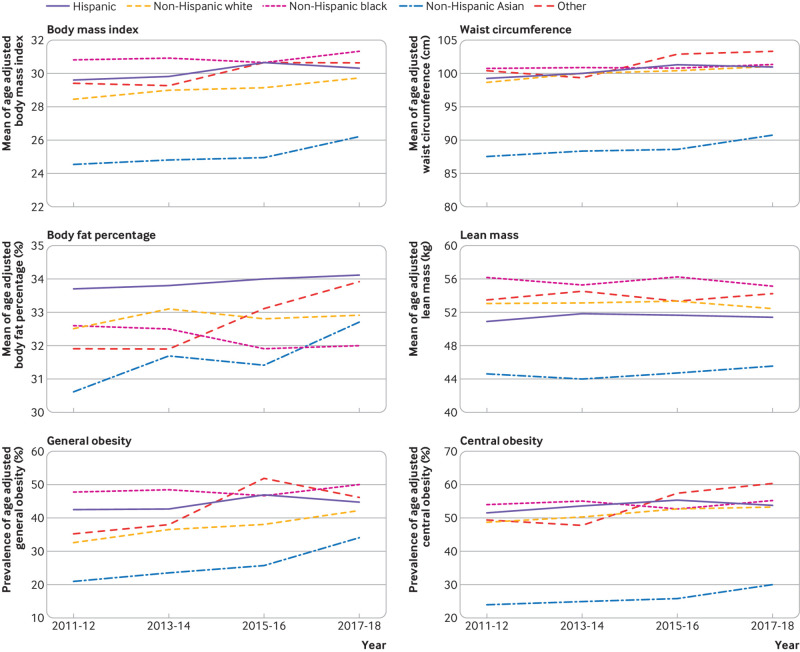

For the overall population, age adjusted mean body mass index increased significantly from 28.7 (95% confidence interval 28.2 to 29.1) in 2011-12 to 29.8 (29.2 to 30.4) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.001). We observed significant increases among people in the Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic Asian groups (P for trend<0.05; fig 1 and table 1). The increases observed in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white groups were mainly in men, while for non-Hispanic Asians, the increase was observed in both sexes. The age adjusted mean body mass index did not change significantly among people in the non-Hispanic black group (P for trend=0.33), although they had the largest body mass index values (table 1). Appendix table 3 shows unadjusted mean body mass index and the trends.

Fig 1.

Trends in obesity and adiposity measures by race or ethnicity among adults in the United States, 2011-18

Table 1.

Trends in age adjusted mean body mass index (95% confidence interval) by race or ethnicity: United States, 2011-18 (n=21 093)

| Variable | Age adjusted body mass index | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 2013-14 | 2015-16 | 2017-18 | ||

| Overall* | 28.7 (28.2 to 29.1) | 29.1 (28.7 to 29.5) | 29.4 (28.8 to 29.9) | 29.8 (29.2 to 30.4) | 0.001 |

| All participants† | |||||

| Hispanic | 29.6 (29.1 to 30.1) | 29.8 (29.2 to 30.4) | 30.6 (29.9 to 31.3) | 30.3 (29.8 to 30.8) | 0.01 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 28.4 (27.8 to 28.9) | 29.0 (28.5 to 29.5) | 29.1 (28.5 to 29.7) | 29.7 (28.8 to 30.5) | 0.006 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 30.8 (30.2 to 31.4) | 30.9 (30.2 to 31.5) | 30.6 (29.9 to 31.3) | 31.3 (30.7 to 31.9) | 0.33 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 24.5 (24.1 to 25.0) | 24.8 (24.4 to 25.2) | 24.9 (24.6 to 25.2) | 26.2 (25.9 to 26.5) | <0.001 |

| Other | 29.4 (27.4 to 31.5) | 29.2 (27.7 to 30.6) | 30.6 (29.5 to 31.6) | 30.6 (29.3 to 31.8) | 0.20 |

| Men‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 29.2 (28.7 to 29.7) | 29.3 (28.5 to 30.1) | 30.0 (29.3 to 30.7) | 30.3 (29.7 to 31.0) | 0.01 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 28.4 (27.9 to 28.9) | 28.9 (28.4 to 29.3) | 29.1 (28.4 to 29.8) | 29.8 (29.0 to 30.6) | 0.002 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 29.0 (28.4 to 29.5) | 28.9 (28.2 to 29.5) | 29.0 (28.2 to 29.8) | 29.4 (28.8 to 30.0) | 0.22 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 24.9 (24.4 to 25.4) | 25.4 (24.9 to 25.9) | 25.3 (24.9 to 25.6) | 26.9 (26.4 to 27.4) | <0.001 |

| Other | 30.5 (26.9 to 34.1) | 28.6 (26.5 to 30.7) | 30.1 (28.2 to 32.0) | 30.2 (28.5 to 32.0) | 0.93 |

| Women‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 30.0 (29.4 to 30.6) | 30.3 (29.5 to 31.1) | 31.2 (30.4 to 31.9) | 30.3 (29.6 to 31.0) | 0.18 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 28.3 (27.6 to 29.1) | 29.1 (28.5 to 29.7) | 29.1 (28.4 to 29.8) | 29.6 (28.4 to 30.8) | 0.07 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 32.4 (31.7 to 33.1) | 32.5 (31.8 to 33.3) | 31.9 (30.9 to 32.8) | 32.8 (31.9 to 33.8) | 0.62 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 24.2 (23.6 to 24.8) | 24.3 (23.6 to 24.9) | 24.6 (24.1 to 25.1) | 25.6 (25.0 to 26.1) | <0.001 |

| Other | 28.4 (26.3 to 30.4) | 29.8 (27.8 to 31.7) | 30.9 (29.4 to 32.3) | 31.2 (29.6 to 32.8) | 0.01 |

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

P for trend adjusted for age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

P for trend adjusted for age and sex.

P for trend adjusted for age.

Waist circumference

For the overall population, age adjusted mean waist circumference increased from 98.4 cm (95% confidence interval 97.4 to 99.5 cm) in 2011-12 to 100.5 cm (98.9 to 102.1 cm) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.01). We observed significant increases among people in the Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic Asian groups (P for trend<0.05; fig 1 and table 2). When stratified by sex, the increases in the Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic Asian groups occurred only in men (table 2). The age adjusted mean waist circumference did not change significantly among people in the non-Hispanic black group (P for trend=0.50). Appendix table 4 shows unadjusted mean waist circumference and the trends.

Table 2.

Trends in age adjusted mean waist circumference (95% confidence interval) by race or ethnicity: United States, 2011-18 (n=20 080)

| Variable | Age adjusted waist circumference (cm) | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 2013-14 | 2015-16 | 2017-18 | ||

| Overall* | 98.4 (97.4 to 99.5) | 99.3 (98.6 to 100.1) | 100.0 (98.6 to 101.5) | 100.5 (98.9 to 102.1) | 0.01 |

| All participants† | |||||

| Hispanic | 99.2 (97.9 to 100.4) | 100.0 (98.1 to 101.9) | 101.3 (100.1 to 102.5) | 100.9 (99.8 to 102.1) | 0.04 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 98.6 (97.3 to 99.8) | 99.7 (98.6 to 100.7) | 100.4 (98.8 to 101.9) | 100.9 (98.7 to 103.0) | 0.03 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 100.7 (99.5 to 101.9) | 100.8 (99.4 to 102.1) | 100.7 (98.6 to 102.8) | 101.3 (99.8 to 102.8) | 0.50 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 87.4 (86.2 to 88.5) | 88.3 (87.2 to 89.3) | 88.5 (87.6 to 89.4) | 90.6 (89.8 to 91.5) | <0.001 |

| Other | 100.3 (95.1 to 105.4) | 99.3 (95.2 to 103.4) | 102.8 (100.4 to 105.2) | 103.2 (100.3 to 106.2) | 0.21 |

| Men‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 101.1 (99.6 to 102.7) | 101.7 (99.3 to 104.1) | 102.5 (101.0 to 103.9) | 103.6 (102.2 to 105.1) | 0.048 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 101.6 (100.2 to 102.9) | 102.7 (101.4 to 104.1) | 103.2 (101.2 to 105.1) | 104.0 (101.9 to 106.2) | 0.042 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 99.3 (98.0 to 100.7) | 98.5 (96.5 to 100.5) | 99.2 (96.9 to 101.6) | 99.9 (97.9 to 101.8) | 0.52 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 90.1 (88.8 to 91.4) | 91.1 (90.0 to 92.3) | 91.5 (90.2 to 92.9) | 95.0 (94.0 to 96.0) | <0.001 |

| Other | 105.5 (97.3 to 113.8) | 100.9 (95.3 to 106.6) | 104.4 (100.0 to 108.7) | 105.0 (100.1 to 109.8) | 0.88 |

| Women‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 97.2 (95.6 to 98.8) | 98.3 (96.0 to 100.6) | 100.0 (98.8 to 101.3) | 98.2 (96.6 to 99.8) | 0.19 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 95.7 (94.1 to 97.2) | 96.7 (95.4 to 98.0) | 97.6 (95.9 to 99.3) | 97.9 (95.0 to 100.8) | 0.09 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 102.0 (100.6 to 103.3) | 102.8 (101.4 to 104.2) | 102.0 (99.4 to 104.6) | 102.7 (100.9 to 104.4) | 0.66 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 84.9 (83.4 to 86.3) | 85.8 (84.1 to 87.4) | 85.6 (84.3 to 87.0) | 86.6 (85.3 to 87.9) | 0.08 |

| Other | 94.6 (91.0 to 98.1) | 97.5 (92.0 to 103.1) | 101.0 (98.3 to 103.8) | 101.0 (97.9 to 104.1) | 0.01 |

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

P for trend adjusted for age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

P for trend adjusted for age and sex.

P for trend adjusted for age.

Body fat percentage

For the overall population, age adjusted body fat percentage did not change significantly: 32.6% (95% confidence interval 32.0% to 33.2%) in 2011-12 and 33.0% (32.4% to 33.7%) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.91). Body fat percentage remained stable among most racial or ethnic groups, except for the non-Hispanic Asian group, among which the age adjusted body fat percentage increased from 30.6% (29.8% to 31.4%) in 2011-12 to 32.7% (32.0% to 33.4%) in 2017-18 (P=0.001; fig 1 and table 3). Moreover, the increase was mainly present in non-Hispanic Asian men, in whom the age adjusted body fat percentage increased from 25.5% (24.7% to 26.4%) in 2011-12 to 28.2% (27.7% to 28.7%) in 2017-18 (P for trend<0.001). Among non-Hispanic Asian women, the body fat percentage was relatively stable at around 37% (P for trend=0.32). Appendix table 5 shows unadjusted body fat percentage and the trends.

Table 3.

Trends in age adjusted mean body fat percentage (95% confidence interval) by race or ethnicity: United States, 2011-18 (n=10 864)*

| Variable | Age adjusted body fat percentage | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 2013-14 | 2015-16 | 2017-18 | ||

| Overall† | 32.6 (32.0 to 33.2) | 33.1 (32.5 to 33.6) | 32.9 (32.2 to 33.5) | 33.0 (32.4 to 33.7) | 0.91 |

| All participants‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 33.7 (32.8 to 34.6) | 33.8 (32.9 to 34.8) | 34.0 (33.2 to 34.8) | 34.1 (33.3 to 35.0) | 0.53 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 32.5 (31.8 to 33.2) | 33.1 (32.3 to 33.9) | 32.8 (32.0 to 33.5) | 32.9 (32.1 to 33.7) | 0.42 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 32.6 (31.9 to 33.2) | 32.5 (31.7 to 33.4) | 31.9 (30.7 to 33.2) | 32.0 (30.6 to 33.4) | 0.69 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 30.6 (29.8 to 31.4) | 31.7 (31.1 to 32.2) | 31.4 (30.8 to 32.0) | 32.7 (32.0 to 33.4) | 0.001 |

| Other | 31.9 (29.9 to 33.8) | 31.9 (29.8 to 34.1) | 33.1 (30.3 to 35.9) | 33.9 (32.0 to 35.9) | 0.06 |

| Men§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 27.8 (27.1 to 28.5) | 28.0 (27.0 to 28.9) | 28.4 (27.6 to 29.2) | 28.6 (27.5 to 29.6) | 0.31 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 27.1 (26.5 to 27.7) | 27.9 (27.0 to 28.9) | 26.8 (26.1 to 27.6) | 27.2 (26.5 to 27.9) | 0.44 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 25.0 (24.5 to 25.5) | 25.0 (24.2 to 25.8) | 24.9 (23.8 to 26.1) | 25.5 (24.3 to 26.6) | 0.67 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 25.5 (24.7 to 26.4) | 26.7 (25.9 to 27.5) | 26.8 (26.2 to 27.4) | 28.2 (27.7 to 28.7) | <0.001 |

| Other | 28.1 (25.8 to 30.4) | 26.4 (24.2 to 28.6) | 27.1 (23.8 to 30.4) | 28.3 (26.1 to 30.6) | 0.62 |

| Women§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 40.3 (39.5 to 41.1) | 40.0 (39.3 to 40.7) | 40.2 (39.6 to 40.9) | 40.0 (39.3 to 40.8) | 0.82 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 38.3 (37.6 to 39.0) | 38.5 (37.9 to 39.0) | 38.3 (37.3 to 39.2) | 38.0 (36.6 to 39.5) | 0.65 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 39.7 (38.7 to 40.6) | 39.7 (39.1 to 40.4) | 38.9 (38.3 to 39.5) | 39.2 (37.8 to 40.6) | 0.32 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 36.2 (34.9 to 37.4) | 36.5 (36.0 to 37.1) | 36.4 (35.2 to 37.6) | 37.1 (35.7 to 38.4) | 0.32 |

| Other | 36.4 (34.2 to 38.6) | 38.2 (36.5 to 39.9) | 38.4 (36.2 to 40.5) | 39.9 (38.0 to 41.8) | 0.01 |

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

Percentage body fat was available among adults aged 20-59 years.

P for trend adjusted for age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

P for trend adjusted for age and sex.

P for trend adjusted for age.

We also calculated distributions for total body fat overall and by race or ethnicity from 2011 to 2018 (appendix table 6). Additionally, we calculated the age adjusted mean body mass index, waist circumference, and age adjusted prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity among adults aged 20-59 years (appendix table 7).

Lean mass

For the overall population, age adjusted mean lean mass remained stable at 52.7 kg (95% confidence interval 52.0 to 53.4 kg) in 2011-12 and 52.1 kg (51.3 to 52.9 kg) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.60). However, we observed significant decreases among people in the non-Hispanic black group, from 56.1 kg (55.2 to 57.0 kg) in 2011-12 to 55.2 kg (54.4 to 56.0 kg) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.04), and the decrease was mainly present in women (P for trend=0.03). Among non-Hispanic Asians, the mean lean mass increased from 44.6 kg (43.7 to 45.4 kg) in 2011-12 to 45.5 kg (44.3 to 46.8 kg) in 2017-18, and the increase was mainly present in men (P for trend=0.01). The age adjusted mean lean mass remained stable in people in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white groups (fig 1 and table 4). Appendix table 8 shows unadjusted mean lean mass and the trends.

Table 4.

Trends in age adjusted mean lean mass (95% confidence interval) by race or ethnicity: United States, 2011-18 (n=10 864)*

| Variable | Age adjusted lean mass (kg) | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 2013-14 | 2015-16 | 2017-18 | ||

| Overall† | 52.7 (52.0 to 53.4) | 52.6 (51.7 to 53.6) | 52.8 (51.9 to 53.6) | 52.1 (51.3 to 52.9) | 0.60 |

| All participants‡ | |||||

| Hispanic | 50.9 (50.1 to 51.7) | 51.8 (50.4 to 53.2) | 51.6 (50.9 to 52.3) | 51.4 (50.5 to 52.3) | 0.27 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 53.1 (52.1 to 54.1) | 53.1 (51.8 to 54.4) | 53.3 (52.3 to 54.3) | 52.4 (51.2 to 53.5) | 0.66 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 56.1 (55.2 to 57.0) | 55.3 (53.8 to 56.8) | 56.2 (55.4 to 56.9) | 55.2 (54.4 to 56.0) | 0.04 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 44.6 (43.7 to 45.4) | 43.9 (43.0 to 44.8) | 44.7 (44.2 to 45.3) | 45.5 (44.3 to 46.8) | 0.01 |

| Other | 53.5 (49.1 to 58.0) | 54.5 (50.3 to 58.7) | 53.4 (48.5 to 58.2) | 54.2 (52.2 to 56.1) | 0.76 |

| Men§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 58.8 (57.5 to 60.1) | 59.9 (58.3 to 61.5) | 58.9 (57.8 to 60.0) | 60.3 (59.0 to 61.5) | 0.26 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 61.6 (60.6 to 62.7) | 61.7 (60.1 to 63.2) | 62.0 (60.4 to 63.6) | 61.2 (59.7 to 62.8) | 0.83 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 63.2 (62.2 to 64.1) | 62.8 (61.2 to 64.4) | 63.9 (62.4 to 65.5) | 62.7 (61.2 to 64.2) | 0.81 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 52.2 (51.0 to 53.3) | 52.2 (51.2 to 53.2) | 52.3 (51.2 to 53.3) | 54.8 (53.2 to 56.4) | 0.01 |

| Other | 64.4 (59.3 to 69.4) | 61.9 (57.2 to 66.5) | 62.5 (57.9 to 67.1) | 62.7 (58.3 to 67.0) | 0.53 |

| Women§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 41.9 (41.2 to 42.6) | 43.1 (41.8 to 44.5) | 43.4 (42.7 to 44.1) | 42.1 (41.5 to 42.7) | 0.65 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 44.0 (43.2 to 44.8) | 44.2 (43.0 to 45.4) | 45.3 (44.3 to 46.2) | 44.4 (43.2 to 45.6) | 0.28 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 49.5 (48.6 to 50.4) | 48.2 (46.8 to 49.6) | 48.5 (47.3 to 49.6) | 47.1 (45.2 to 49.0) | 0.03 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 36.2 (35.5 to 37.0) | 35.8 (34.9 to 36.8) | 36.5 (35.4 to 37.7) | 36.6 (36.0 to 37.2) | 0.23 |

| Other | 40.9 (37.9 to 43.9) | 46.2 (42.4 to 49.9) | 45.3 (43.5 to 47.0) | 45.4 (43.9 to 46.9) | 0.07 |

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

Percentage of body fat was available among adults aged 20-59 years.

P for trend adjusted for age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

P for trend adjusted for age and sex.

P for trend adjusted for age.

General obesity

The overall age adjusted prevalence of general obesity increased significantly regardless of body mass index cut-off points that were used for non-Hispanic Asians (fig 1 and table 5). The age adjusted prevalence of obesity, defined with Asian specific cut-off points, increased from 20.8% (95% confidence interval 17.2% to 24.4%) in 2011-12 to 34.2% (29.8% to 38.6%) in 2017-18 among Asians (P for trend<0.001), which is much higher than that defined using the cut-off points for the general population (appendix table 9). We also observed significant increases in people in the non-Hispanic white group (P for trend<0.05). The prevalence of general obesity has leveled off in the non-Hispanic black group (P for trend=0.52), although it is still the highest figure (table 5). There was no significant change among Hispanics (P for trend=0.14). Appendix table 10 shows the total number of participants and the number of participants with obesity across NHANES cycles; appendix table 11 shows the unadjusted prevalence of general obesity and the trends.

Table 5.

Trends in prevalence of age adjusted obesity (95% confidence interval) by race or ethnicity: United States, 2011-18

| Variable | Age adjusted prevalence (%) | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-12 | 2013-14 | 2015-16 | 2017-18 | ||

| General obesity defined by body mass index (n=21 093) | |||||

| Overall* (specific cut-off points for Asians) | 35.4 (32.5 to 38.3) | 38.3 (36.4 to 40.2) | 40.3 (37.0 to 42.7) | 43.4 (39.8 to 47.0) | <0.001 |

| Overall* (cut-off points for general population) | 34.9 (32.0 to 37.8) | 37.7 (35.8 to 39.7) | 39.6 (36.0 to 43.1) | 42.4 (38.6 to 46.3) | <0.001 |

| All participants† | |||||

| Hispanic | 42.5 (39.0 to 46.0) | 42.6 (38.1 to 47.0) | 47.0 (42.5 to 51.5) | 44.8 (41.4 to 48.1) | 0.14 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 32.6 (28.9 to 36.4) | 36.4 (34.0 to 38.8) | 37.9 (34.0 to 41.8) | 42.2 (36.8 to 47.6) | 0.002 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 47.8 (44.4 to 51.3) | 48.4 (44.1 to 52.7) | 46.8 (41.9 to 51.7) | 49.6 (46.5 to 52.8) | 0.52 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian‡ | 20.8 (17.2 to 24.4) | 23.5 (20.0 to 27.0) | 25.5 (20.0 to 31.1) | 34.2 (29.8 to 38.6) | <0.001 |

| Other | 35.2 (22.3 to 48.0) | 38.0 (28.8 to 47.2) | 51.9 (44.2 to 59.5) | 46.3 (35.6 to 57.1) | 0.098 |

| Men§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 40.1 (35.7 to 44.5) | 37.9 (31.9 to 43.8) | 43.1 (37.0 to 49.2) | 45.7 (41.9 to 49.6) | 0.04 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 32.4 (29.6 to 35.3) | 34.7 (31.3 to 38.1) | 37.9 (32.0 to 43.7) | 44.7 (36.8 to 52.6) | 0.002 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 37.1 (33.0 to 41.2) | 38.0 (32.6 to 43.3) | 36.9 (31.5 to 42.2) | 41.1 (36.3 to 45.9) | 0.26 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian‡ | 21.9 (17.3 to 26.5) | 25.1 (18.8 to 31.4) | 25.6 (20.4 to 30.9) | 37.2 (30.4 to 43.9) | <0.001 |

| Other | 40.6 (19.0 to 62.3) | 41.0 (24.8 to 57.1) | 53.0 (40.4 to 65.7) | 42.1 (29.4 to 54.9) | 0.87 |

| Women§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 44.4 (40.0 to 48.8) | 46.9 (41.2 to 52.6) | 50.6 (46.2 to 55.0) | 43.7 (39.3 to 48.0) | 0.78 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 32.8 (27.1 to 38.6) | 38.2 (34.7 to 41.7) | 38.0 (33.9 to 42.0) | 39.8 (33.7 to 46.0) | 0.09 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 56.6 (52.3 to 61.0) | 57.2 (53.6 to 60.7) | 54.8 (49.9 to 59.8) | 56.9 (52.8 to 61.0) | 0.91 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian‡ | 19.8 (15.2 to 24.3) | 21.8 (16.9 to 26.7) | 25.0 (18.1 to 32.0) | 31.5 (26.4 to 36.7) | 0.001 |

| Other | 28.7 (16.8 to 40.7) | 36.1 (24.5 to 47.6) | 50.0 (38.5 to 61.5) | 54.3 (42.1 to 66.5) | 0.002 |

| Abdominal obesity defined by waist circumference (n=20 080) | |||||

| Overall* | 54.5 (51.2 to 57.8) | 56.3 (54.8 to 57.7) | 58.4 (53.9 to 62.9) | 59.1 (55.6 to 62.7) | 0.02 |

| All participants† | |||||

| Hispanic | 57.8 (54.7 to 60.9) | 60.4 (55.9 to 64.8) | 62.4 (59.1 to 65.8) | 60.6 (57.6 to 63.7) | 0.24 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 54.4 (50.1 to 58.8) | 56.2 (54.0 to 58.4) | 59.5 (54.4 to 64.6) | 59.9 (55.0 to 64.8) | 0.052 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 60.8 (57.9 to 63.7) | 62.1 (58.5 to 65.7) | 59.0 (54.1 to 63.8) | 62.3 (58.8 to 65.9) | 0.75 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 24.7 (21.5 to 27.9) | 25.8 (21.7 to 29.9) | 26.8 (22.8 to 30.8) | 31.9 (29.1 to 34.7) | 0.001 |

| Other | 55.3 (40.9 to 69.8) | 53.2 (41.8 to 64.5) | 65.0 (55.3 to 74.7) | 68.4 (60.1 to 76.7) | 0.04 |

| Men§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 43.9 (38.6 to 49.2) | 45.8 (41.0 to 50.6) | 47.5 (42.6 to 52.4) | 49.5 (46.1 to 52.8) | 0.20 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 45.2 (41.6 to 48.7) | 48.2 (44.8 to 51.6) | 51.2 (44.3 to 58.1) | 54.0 (46.9 to 61.0) | 0.02 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 41.2 (37.4 to 45.0) | 40.5 (35.7 to 45.4) | 40.3 (34.5 to 46.1) | 44.0 (39.9 to 48.1) | 0.36 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 14.0 (10.2 to 17.8) | 13.6 (8.0 to 19.2) | 15.6 (11.5 to 19.7) | 21.3 (17.7 to 24.8) | 0.01 |

| Other | 47.4 (26.9 to 67.9) | 41.4 (24.0 to 58.8) | 50.6 (39.8 to 61.4) | 58.5 (43.8 to 73.2) | 0.30 |

| Women§ | |||||

| Hispanic | 71.1 (67.4 to 74.8) | 74.7 (68.4 to 81.0) | 77.2 (74.0 to 80.5) | 71.8 (67.7 to 75.8) | 0.73 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 63.9 (58.4 to 69.5) | 64.2 (61.1 to 67.3) | 67.7 (62.9 to 72.4) | 65.8 (59.8 to 71.8) | 0.41 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 77.2 (73.3 to 81.0) | 81.1 (78.5 to 83.6) | 74.8 (70.4 to 79.3) | 78.0 (73.7 to 82.4) | 0.68 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 33.9 (29.7 to 38.2) | 36.0 (30.1 to 41.9) | 36.7 (32.5 to 41.0) | 41.0 (36.4 to 45.6) | 0.03 |

| Other | 64.3 (53.8 to 74.7) | 66.9 (55.6 to 78.3) | 79.1 (69.9 to 88.4) | 80.9 (74.2 to 87.7) | 0.004 |

Race and Hispanic ethnicity were classified based on the 1997 Office of Management and Budget standards.

P for trend adjusted for age, sex, and race or ethnicity.

P for trend adjusted for age and sex.

Obesity was defined using specific cut-off point for Asians (body mass index≥27.5).

P for trend adjusted for age.

Abdominal obesity

The overall age adjusted abdominal obesity increased from 54.5% (95% confidence interval 51.2% to 57.8%) in 2011-12 to 59.1% (55.6% to 62.7%) in 2017-18 (P for trend=0.02). However, we only observed significant increases among non-Hispanic white men (P for trend=0.02) and non-Hispanic Asian men (P for trend=0.01) and women (P for trend=0.03; fig 1 and table 5). Appendix table 11 shows the unadjusted prevalence of abdominal obesity and the trends.

Discussion

Principal findings

This study was based on a nationally representative population of multiracial or ethnic background. We reported the most recent national trend estimates of obesity, abdominal obesity, and body composition, and their other racial or ethnic disparities among US adults from 2011-12 to 2017-18. Overall, we found that obesity prevalence remained high and was increasing in the US, although with variation among racial or ethnic groups. The age adjusted mean body mass index and waist circumference, and obesity and abdominal obesity increased from 2011-12 to 2017-18. The age adjusted body fat percentage and lean mass, only available for adults aged 29-59 years, did not change during this period in most racial or ethnic groups.

The trends differed across racial or ethnic groups. Estimates for people in the non-Hispanic black group were plateauing at a high level for all measures, but showed a decrease in lean body mass. Non-Hispanic Asians were the only group that had increases in all adiposity measures and lean mass. People in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white groups showed increases in body mass index and waist circumference, but not in body fat percentage and lean body mass. In every racial or ethnic group, the prevalence of general obesity in 2017-18 was higher than the goal of 30.5% in the Healthy People 2020 programme.37 38

Comparison with other studies

This study investigated national estimates of body composition among US adults in recent years. The findings provide important information about adiposity directly measured by dual energy x ray absorptiometry, whereas previous studies usually reported obesity defined by body mass index as a proxy of adiposity. Overall, age adjusted body fat percentages and lean masses were stable among US adults aged 20-59 years during 2011-18, with considerable disparities in race or ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Asians, especially men, showed an increase in body fat percentage, while all other racial or ethnic groups remained relatively stable. Compared with reports from 1999 to 2004 (mean body fat percentage 28.2%; total body fat 25.4 kg), body fat percentage and total body fat in the current study were much higher overall, and in each racial or ethnic group.21 An interesting finding was that non-Hispanic Asians showed an increase in lean mass, while non-Hispanic black people showed a decrease, especially among women.

Most previous studies reporting the national prevalence of obesity have focused on body mass index defined general obesity.9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Our findings about body mass index and general obesity defined by the body mass index cut-off point for the general population were consistent with previous reports.9 11 16 We also reported the prevalence of obesity in non-Hispanic Asians using the Asian specific cut-off point. Using this cut-off point, we found that in 2011-12, 20.8% of Asians were obese, which increased to 34.2% in 2017-18. When the Asian specific cut-off point was compared with the cut-off point for the general population, around three million additional non-Hispanic Asians were classified as obese in 2017-18. Furthermore, our findings provide the most recent national estimate of waist circumference and abdominal obesity. During 2011-18, increases in waist circumference occurred among people in the Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic Asian groups, but not in the non-Hispanic black group. Additionally, we found that the overall prevalence of abdominal obesity rose from 54.5% in 2011-12 to 59.1% in 2017-18, an increase mostly attributed to non-Hispanic Asians (increased by 29.1%). Previous reports showed that waist circumference increased from 95.5 cm in 1999-2000 to 98.5 cm in 2011-12,17 while among Asian Americans, it increased from 87.1 cm in 2011-12 to 88.2 cm in 2013-14.19 Meanwhile, the overall prevalence of abdominal obesity increased from 46.4% in 1999-2000 to 54.2% in 2011-12.17 These previous reports combined with our findings suggest that waist circumference and abdominal obesity have increased steadily in the US during the past two decades, with variations across race or ethnicity.

Several factors could serve as potential explanations for the increase in obesity prevalence in the US and worldwide: increased sedentary behavior,39 40 insufficient sleep,41 42 environmental exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals,43 44 45 and continued suboptimal diet quality.46 Social and environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status, social capital, occupational status (stress, shift work, and unemployment), and neighborhood environments (building environment and food environment) might also contribute at different levels, including interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy levels.47 48 Moreover, in contrast to the increased body mass index and waist circumference, body fat percentages and lean mass remained relatively stable during these years. The underlying reasons are unclear and warrant further exploration, although body mass index and waist circumference do not necessarily correspond to body fat percentage.

Racial or ethnic disparities were observed in all the obesity and adiposity measures. In this study, obesity and adiposity measures plateaued among people in the non-Hispanic black group, although they remained high. This leveling off might be attributable to improvements in lifestyle factors, such as improved diet quality,46 and increased rate of adhering to the physical activity guidelines for Americans for aerobic activity.39 However, the mean lean masses decreased among people in the non-Hispanic black group from 2011 to 2018, which could prompt negative health implications. For non-Hispanic Asians, we observed much lower body mass index values, waist circumferences, and lean masses than other racial or ethnic groups. However, the body fat percentage in non-Hispanic Asians was comparable to people in the non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black groups. These findings are consistent with previous data showing that Asians have higher adiposity than non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black people at a given body mass index.49 Additionally, these data could explain why increased health risks, such as insulin resistance, high triglycerides, and high cholesterol, begin at a lower body mass index among Asians than among white adults.50 51

The non-Hispanic Asian group is the only group that showed increases in all the obesity and adiposity measures, which suggests a potential increase in medical and financial burden associated with obesity among non-Hispanic Asians in the future. However, most previous studies, such as those about the secular changes in physical activity and diet, have classified non-Hispanic Asians into ‘other’ racial or ethnic groups.39 46 Therefore, we cannot speculate on the potential explanations for the increase in adiposity measures in non-Hispanic Asians. Continued increases in some adiposity measures were also observed among people in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white groups. All increases in adiposity measures were more pronounced among men than women. Increased effort is needed to develop more effective obesity control programmes and to further ameliorate health problems caused by the obesity epidemic, especially among vulnerable populations.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of data from NHANES, which provides an opportunity to estimate the national trends in a comprehensive set of obesity and adiposity measures, including objectively measured body weight, height, waist circumference, and body composition. Moreover, a large enough sample size was used to separately identify non-Hispanic Asians from other races or ethnicities, allowing us to show the distinct but neglected pattern of the obesity epidemic among Asian Americans.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, although NHANES remains the leading national survey with high response rates, like many other national face-to-face surveys,52 response rates declined over time, which might be subject to selection bias. However, the National Center for Health Statistics has evaluated the NHANES data and conducted enhanced weighting adjustment to minimize the potential nonresponse bias, and we have incorporated the sampling weights in analyses according to NHANES analytic guidelines.29 34 NHANES data remain the best resource to estimate obesity prevalence among US adults and continue to be used in reports by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11

Secondly, in NHANES 2011-18, body composition (body fat, lean mass) was measured for adults aged 20-59 years, but not those aged 60 years or older. Therefore, we could not estimate the distribution in the older population. Additionally, some NHANES participants were not eligible for a dual energy x ray absorptiometry scan because of excessive weight or height; however, the proportion of these participants was small (0.1%). Some participants did not have dual energy x ray absorptiometry data because they refused to have a scan, or for other reasons such as medical tests. Therefore, the estimates in this study might not fully represent the body composition among the general population. Thirdly, as in previous reports by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,14 15 53 54 we did not perform adjustments for multiple comparisons in this study, which could result in type I errors.

Conclusions

This nationally representative survey provides an important picture of trends in various obesity and adiposity measures in adults in the US. Variations across race or ethnicity were observed for trends in the obesity and adiposity measures, including body mass index, waist circumference, body fat percentage, lean mass, general obesity, and abdominal obesity, from 2011 to 2018. People in the non-Hispanic black group showed a leveling off in most measures, although their figures remained high, and a decrease in lean mass. Additionally, we observed consistent increases in all measures among non-Hispanic Asians, which warrants further attention.

What is already known on this topic

Previous studies have reported an increasing trend in obesity based on body mass index and waist circumference, which are useful measures but cannot directly assess body fat or adiposity

Population data that examine recent national trends in imaging assessed adiposity, expressed as body fat percentage, are lacking in the United States

What this study adds

In a series of nationally representative cross sectional surveys, people in the non-Hispanic black group showed a leveling off in all adiposity measures (body mass index, waist circumference, body fat percentage, general obesity, and abdominal obesity), and a decrease in lean mass from 2011 to 2018

Increases in all measures were observed for non-Hispanic Asians, while people in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic white groups showed increased body mass index and waist circumference, but body fat percentage and lean mass remained stable

This study has updated recent trends in obesity by race or ethnicity, and provided up-to-date estimates for national trends in body composition among US adults

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: supplementary online content

Contributors: WB has full access to all of the data in this study and has final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. WB and BL contributed to the conception and design of the study. BL performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. WB is guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was partly supported by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (R21 HD091458). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the National Institutes of Health for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: NHANES has been approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board.

Data sharing: Data available from the NHANES website (wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/default.aspx).

The manuscript’s guarantor (WB) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to individual study participants because all participants are deidentified. The results of this study will be disseminated as medical manuscripts and will be publicly available on PubMed Central.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Dwivedi AK, Dubey P, Cistola DP, Reddy SY. Association between obesity and cardiovascular outcomes: updated evidence from meta-analysis studies. Curr Cardiol Rep 2020;22:25. 10.1007/s11886-020-1273-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Avila C, Holloway AC, Hahn MK, et al. An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr Obes Rep 2015;4:303-10. 10.1007/s13679-015-0164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:71-82. 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1625-38. 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet 2011;378:815-25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hu FB. Obesity epidemiology. Oxford University Press, 2008. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195312911.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallagher D, Visser M, Sepúlveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fatness across age, sex, and ethnic groups? Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:228-39. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention. Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. American Heart Association. World Heart Federation. International Atherosclerosis Society. International Association for the Study of Obesity . Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009;120:1640-5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284-91. 10.1001/jama.2016.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA 2018;319:1723-5. 10.1001/jama.2018.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. National Center for Health Statistics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA 2006;295:1549-55. 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA 2010;303:235-41. 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA 2014;311:806-14. 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Aoki Y, Ogden CL. Differences in obesity prevalence by demographic characteristics and urbanization level among adults in the United States, 2013-2016. JAMA 2018;319:2419-29. 10.1001/jama.2018.7270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fryar CD, Kruszon-Moran D, Gu Q, Ogden CL. Mean body weight, height, waist circumference, and body mass index among adults: United States, 1999-2000 through 2015-2016. Natl Health Stat Report 2018;122:1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ford ES, Maynard LM, Li C. Trends in mean waist circumference and abdominal obesity among US adults, 1999-2012. JAMA 2014;312:1151-3. 10.1001/jama.2014.8362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Min J, Xue H, Kaminsky LA, Cheskin LJ. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:810-23. 10.1093/ije/dyz273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu X, Chen Y, Boucher NL, Rothberg AE. Prevalence and change of central obesity among US Asian adults: NHANES 2011-2014. BMC Public Health 2017;17:678. 10.1186/s12889-017-4689-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tinsley GM, Smith-Ryan AE, Kim Y, et al. Fat-free mass characteristics vary based on sex, race, and weight status in US adults. Nutr Res 2020;81:58-70. 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Balluz LS, Giles WH. Estimates of body composition with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1457-65. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paulose-Ram R, Burt V, Broitman L, Ahluwalia N. Overview of Asian American data collection, release, and analysis: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2018. Am J Public Health 2017;107:916-21. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau. 2017 National Population Projections Tables: Main Series-Projections for the United States: 2017 to 2060. 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html

- 24. WHO Expert Consultation . Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157-63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsu WC, Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Chiang JL, Fujimoto W. BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care 2015;38:150-8. 10.2337/dc14-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Diabetes Association . Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Section 6 in Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2016. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S47-51. 10.2337/dc16-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahluwalia N, Dwyer J, Terry A, Moshfegh A, Johnson C. Update on NHANES dietary data: focus on collection, release, analytical considerations, and uses to inform public policy. Adv Nutr 2016;7:121-34. 10.3945/an.115.009258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen TC CJ, Riddles MK, Mohadjer LK, Fakhouri THI. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015. Sample design and estimation procedures. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2020;2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. An investigation of nonresponse bias and sample characteristics in the 2017−2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2020. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticguidelines/17-18-sampling-variability-nonresponse-508.pdf

- 30.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm

- 31.National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB) Approval. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm

- 32.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Anthropometry Procedures Manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2015-2016/manuals/2016_Anthropometry_Procedures_Manual.pdf

- 33.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Body Composition Procedures Manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/manuals/Body_Composition_Procedures_Manual_2018.pdf

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Analytic Guidelines, 2011-2014 and 2015-2016. 2018. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticguidelines/11-16-analytic-guidelines.pdf

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/NHANESAnalyses/agestandardization/age_standardization_intro.htm

- 36.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Stat Notes 2001:1-10. [PubMed]

- 37.US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020 topics and objectives: Nutrition and weight status. 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/nutrition-and-weight-status/objectives

- 38. Berge JM, Fertig A, Tate A, et al. Who is meeting the Healthy People 2020 objectives? Comparisons between racially/ethnically diverse and immigrant children and adults. Fam Syst Health 2018;36:451-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in adherence to the physical activity guidelines for Americans for aerobic activity and time spent on sedentary behavior among US adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e197597. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murillo R, Albrecht SS, Daviglus ML, Kershaw KN. The role of physical activity and sedentary behaviors in explaining the association between acculturation and obesity among Mexican-American adults. Am J Health Promot 2015;30:50-7. 10.4278/ajhp.140128-QUAN-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Sleep quality and obesity in young subjects: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17:1154-66. 10.1111/obr.12444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jean-Louis G, Grandner MA, Youngstedt SD, et al. Differential increase in prevalence estimates of inadequate sleep among black and white Americans. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1185. 10.1186/s12889-015-2500-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lehmler HJ, Liu B, Gadogbe M, Bao W. Exposure to bisphenol A, bisphenol F, and bisphenol S in U.S. adults and children: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2014. ACS Omega 2018;3:6523-32. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, et al. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocr Rev 2015;36:E1-150. 10.1210/er.2015-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu B, Lehmler HJ, Sun Y, et al. Bisphenol A substitutes and obesity in US adults: analysis of a population-based, cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1:e114-22. 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shan Z, Rehm CD, Rogers G, et al. Trends in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and diet quality among US Adults, 1999-2016. JAMA 2019;322:1178-87. 10.1001/jama.2019.13771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee A, Cardel M, Donahoo WT. Social and environmental factors influencing obesity. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodgers J, Valuev AV, Hswen Y, Subramanian SV. Social capital and physical health: An updated review of the literature for 2007-2018. Soc Sci Med 2019;236:112360. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lear SA, Humphries KH, Kohli S, Birmingham CL. The use of BMI and waist circumference as surrogates of body fat differs by ethnicity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2817-24. 10.1038/oby.2007.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland B, et al. Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med 2011;364:719-29. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wulan SN, Westerterp KR, Plasqui G. Ethnic differences in body composition and the associated metabolic profile: a comparative study between Asians and Caucasians. Maturitas 2010;65:315-9. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Williams D, Brick JM. Trends in U.S. face-to-face household survey nonresponse and level of effort. J Surv Stat Methodol 2018;6:186-211. 10.1093/jssam/smx019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple comparison procedures. JAMA 2014;312:543-4. 10.1001/jama.2014.9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292-9. 10.1001/jama.2016.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: supplementary online content