Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Despite significant recent efforts applied toward the development of efficacious therapies for glioblastoma (GBM) through exploration of GBM’s genome and transcriptome, curative therapeutic strategies remain highly elusive. As such, novel and effective therapeutics are urgently required. In this study, the authors sought to explore the kinomic landscape of GBM from a previously underutilized approach (i.e., spatial heterogeneity), followed by validation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) targeting according to this stepwise kinomic-based novel approach.

METHODS

Twelve GBM tumor samples were obtained and characterized histopathologically from 2 patients with GBM. PamStation peptide-array analysis of these tissues was performed to measure the kinomic activity of each sample. The Ivy GBM database was then utilized to determine the intratumoral spatial localization of BTK activity by investigating the expression of BTK-related transcription factors (TFs) within tumors. Genetic inhibition of BTK family members through lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown was performed to determine their function in the core-like and edge-like GBM neurosphere models. Finally, the small-molecule inhibitor of BTK, ONO/GS-4059, which is currently under clinical investigation in nonbrain cancers, was applied for pharmacological inhibition of regionally specified newly established GBM edge and core neurosphere models.

RESULTS

Kinomic investigation identified two major subclusters of GBM tissues from both patients exhibiting distinct profiles of kinase activity. Comparatively, in these spatially defined subgroups, BTK was the centric kinase differentially expressed. According to the Ivy GBM database, BTK-related TFs were highly expressed in the tumor core, but not in edge counterparts. Short hairpin RNA-mediated gene silencing of BTK in previously established edge- and core-like GBM neurospheres demonstrated increased apoptotic activity with predominance of the sub-G1 phase of core-like neurospheres compared to edge-like neurospheres. Lastly, pharmacological inhibition of BTK by ONO/GS-4059 resulted in growth inhibition of regionally derived GBM core cells and, to a lesser extent, their edge counterparts.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identifies significant heterogeneity in kinase activity both within and across distinct GBM tumors. The study findings indicate that BTK activity is elevated in the classically therapy-resistant GBM tumor core. Given these findings, targeting GBM’s resistant core through BTK may potentially provide therapeutic benefit for patients with GBM.

Keywords: Kinomics, protein kinase, glioblastoma, BTK, ONO/GS-4059, oncology

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and lethal primary brain tumor in adults, comprising 16% of all primary CNS neoplasms and 50% of all primary malignant brain tumor diagnoses.46 Despite multimodal therapeutic strategies combining maximal resection and adjuvant chemotherapy and irradiation, the median survival for patients with GBM has not reached 2 years.45 Tumor heterogeneity appears to be a major contributor to this unsatisfactory outcome.16 Despite the predominance of pathological analyses of GBM heterogeneity, exploration of the dynamic heterogeneity at distinct molecular and cellular levels is fundamental to understanding the notoriously aggressive and recurrent nature of the disease, and to identify potential therapeutic targets.31

Over the past 2 decades, technical advancements in cDNA microarray sequencing and RNA sequencing have provided more precise evaluation of the transcriptome.19,39,54 Although these techniques featured prominently in elucidating molecular mechanisms controlling cellular physiology, defining essential proteins involved in active cellular signal transduction pathways has remained largely understudied due to the limited approaches to measure their activities.21 Enzymes that phosphorylate tyrosine, serine, and threonine residues on other proteins24 control the signaling cascades dictating cell-cycle entry, survival, and differentiation fate in tissues.14 Additionally, protein kinases play a major, if not the only, role in the oncogenic processes that initiate and propagate cancers, including GBM.6 Given several technical and practical limitations, both genetic and biochemical approaches have proven limited in the exploration of the kinome domain.3,33,34 Kinomic analysis is a recently developed powerful means for direct detection of protein function.15 While several different approaches exist, the measurement of peptide substrate phosphorylation by protein microar-rays remains the most reliable and widely applied method to assess kinase activity.15 Kinomic profiling in this manner allows direct measurement of targetable activity, thus overcoming the limitations of genomic analyses or other molecular surrogates.1

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase known to play a pivotal role in B-cell maturation and development.40 Altered BTK activity has been largely implicated in several hematological malignancies,4 and was exploited as a therapeutic target in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).8,51 ONO/GS-4059 is a novel selective and irreversible small-molecule inhibitor of BTK that has been developed to circumvent the broader molecular targeting issues associated with ibrutinib, the classic non-selective BTK inhibitor used in the management of CLL and MCL.12 Recently, the results of a multicenter phase 1 dose-escalation study of ONO/GS-4059 in 90 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies was reported and indicated comparable efficacy to ibrutinib with a lower incidence of associated toxicities.48 Of note, BTK has been associated with glioma tumorigenesis as a novel prognostic marker for poor survival in patients with gliomas.52,55 BTK inhibition appears to be a potentially promising new therapeutic strategy for gliomas as it appears to block proliferation, migration, and invasion properties, inducing apoptosis and autophagy of glioma cells, and targeting the Akt/mTOR pathway in vitro and in vivo.50

In this study, kinomic screening was performed on 12 GBM tissues derived from distinct geographical regions of two GBM patient tumors, which led to the identification of significant BTK activity on one subset of samples. The combined analyses using the Ivy GBM data set,38 followed by preclinical tests with GBM cells harvested from the tumor’s core and edge, determined that BTK acts as a key regulator in GBM tumor cells located in the tumor core, but not the edge. Our data suggest that GBM core cells are largely, if not exclusively, dependent on BTK for their survival, and therefore targeting BTK, in combination with other treatment modalities, would develop into a promising novel therapeutic approach for GBM.

Methods

Ethics

All work related to human tissue was performed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) under an IRB-approved protocol compliant with guidelines set forth by the NIH. Patient-derived specimens were provided to the corresponding scientists after de-identification of the original tumors.

GBM-Derived Neurospheres and Cell Cultures

Glioma neurosphere cultures from clinical samples, previously established regionally derived core (Gd-positive [Gd+] enhancing region) and edge (T2 FLAIR, non-Gd+ enhancing region) GBM neurospheres, and previously established core-like and edge-like GBM neurospheres10,11,23,30,35,36,44 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 medium containing 2% B27 supplement (% volume), 2.5 mg/ml heparin, 20 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF). The bFGF and EGF reagents were added twice a week, and the culture medium was replaced every 10 days. Experiments with neurospheres were performed with cell lines that were cultured for fewer than 40 passages since their initial establishment. Short tandem repeat analysis was performed to confirm cell identity.

Kinomic Analysis

Tissue samples from patients were snap-frozen after collection and stored at −80°C prior to kinomic processing and analysis in the UAB Kinome Core. Tissues were lysed in mammalian protein extraction reagent lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and loaded onto PamGene PamChips (article ID 86312) and analyzed on the PamStation12 utilizing image capture in Evolve2 and kinase peptide phosphorylation analysis in BioNavigator (version 6.3.67.0) as previously described.2,17 Briefly, ly-sates were prepared in kinase buffer and pumped through a multiplexed array of 13–15 amino acid phosphorylatable peptide substrates, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies detect phosphorylation of these probes over multiple pumping cycles and over multiple exposures. These phosphorylation intensities (following background correction) are converted to an exposure-time slope, which is multiplied by 100 and Log2 transformed. These Log2 data, per peptide, per sample, are referred to as signal.

For kinomic data analysis, the kinomic signal was clustered using a geometrical means distance method within BioNavigator to generate heatmaps of the peptide signal. Whole-array comparative analysis to identify altered kinases was conducted using PTK Upstream Kinase (version 6, “UpKin”) within BioNavigator between indicated groups. Selected kinases (mean final score > 1.5) from UpKin output were uploaded by Uniprot ID to MetaCore (portal.genego.com, Clarivate Analytics) and are modeled using an autoexpand network model with canonical pathways deselected, and a maximum size of 50 nodes.

Lentivirus Production and Transduction

Screening of the kinase panel short hairpin RNA (shRNA) from The Mission RNAi Library (Sigma-Aldrich) was performed in 96-well plates as previously described.18 Briefly, DNA preparations were obtained using a large-scale plasmid purification kit (QIAGEN and Roche). HEK293T packaging cells were cotransfected with the pLKO.1 vector encoding the shRNA and the helper plasmids for virus production (psPAX2 and pMGD2), using Trans-IT (Mirus). Before transduction, neurospheres were dissociated mechanically (83 core-like glioma stemlike cells [GSCs]) or with trypsin (528 edge-like GSCs). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 10,000 cells per well in a final volume of 100 μl and transduced at a multiplicity of infection of 10. At 24 hours after transduction, the medium was renewed upon plate centrifugation for 2 minutes at 800 rpm.

High-Throughput Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cell-cycle analysis was performed using propidium iodide (PI) staining assay. Briefly, cells were fixed using 70% ethanol 5 days after viral transduction. After incubation at 4°C overnight, plates were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes. Ethanol was removed, and 200-ml room-temperature cell-cycle staining reagent (0.1% Triton X-100, phosphate-buffered saline, 200 mg/ml DNase-free RNase, 250 mg/ml PI) was added. Cells were resuspended, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes, followed by cell-cycle analysis using a flow cytometer equipped with a high-throughput sampler. To minimize potential artifacts caused by edge effects, the outermost wells were not used.

Cell Viability Assay

Viability of GBM cells was determined using alamarBlue reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were seeded at 3000 cells per well in a 96-well plate, after the indicated period of time alamarBlue reagent was added into each well and 6 hours later fluorescence was measured (excitation 515–565 nm, emission 570–610 nm) using the Synergy HTX multimode reader (BioTek).

Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project RNA-Sequencing Analysis

For RNA-sequencing analysis, raw gene-level values of fragments per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (FPKM) and sample information were downloaded from the Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project (Ivy GAP) website (http://glioblastoma.alleninstitute.org).38 The database includes gene expression data for multiple structural features commonly identified in GBM enriched by laser capture microdissection. To visualize variations in gene expression patterns between structural features, all 25,873 genes of each of the 270 samples were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA). For heatmap analysis, the expression of 4 transcription factors (TFs) downstream of the BTK pathway was analyzed using these 270 samples.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using XLSTAT (version 2018.5), the SPSS statistical package (version 25, IBM Corp.), and GraphPad Prism (version 7.0) software. All data were presented as means ± SDs. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characterization of Intra- and Intertumoral Heterogeneity in GBM Tumors

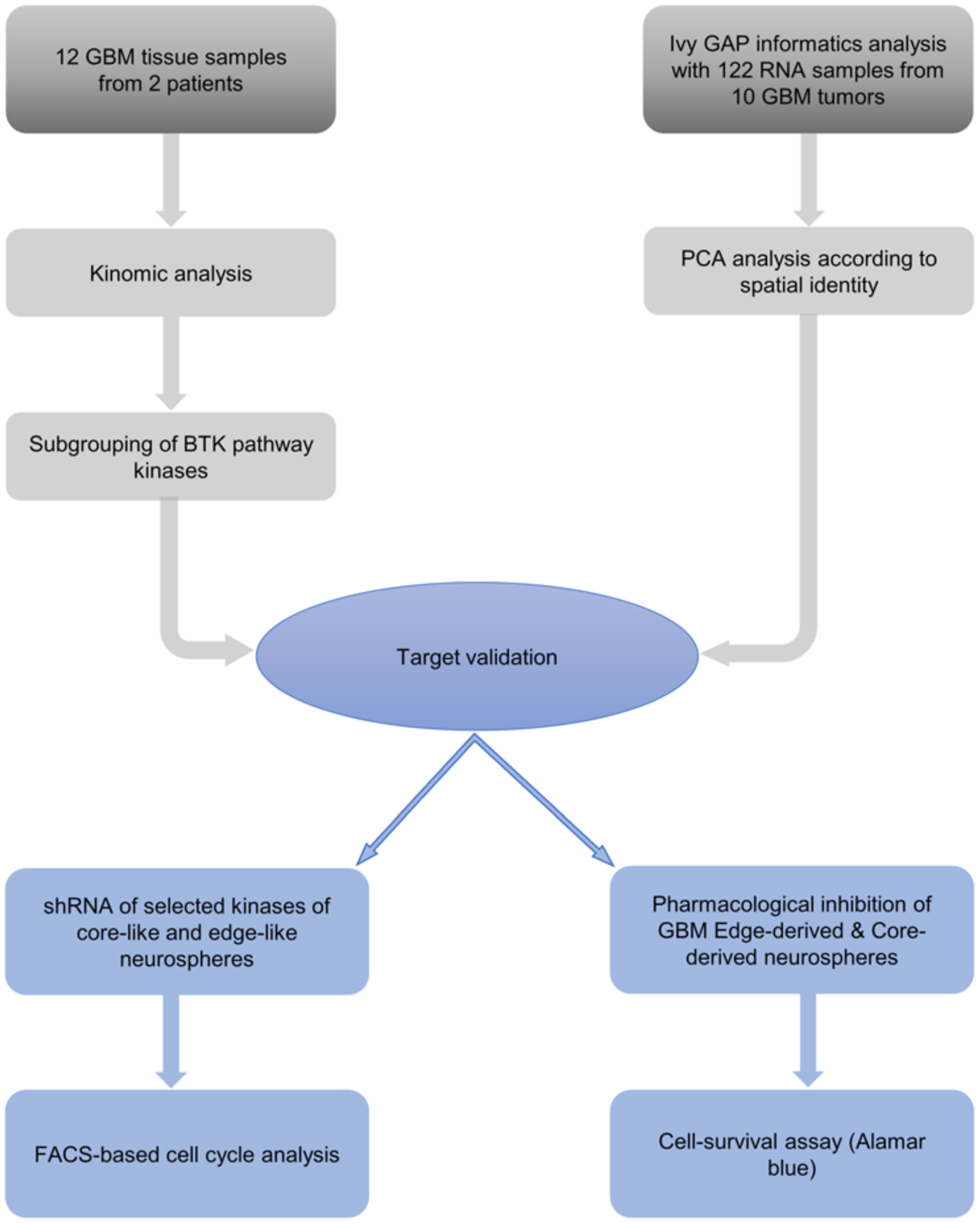

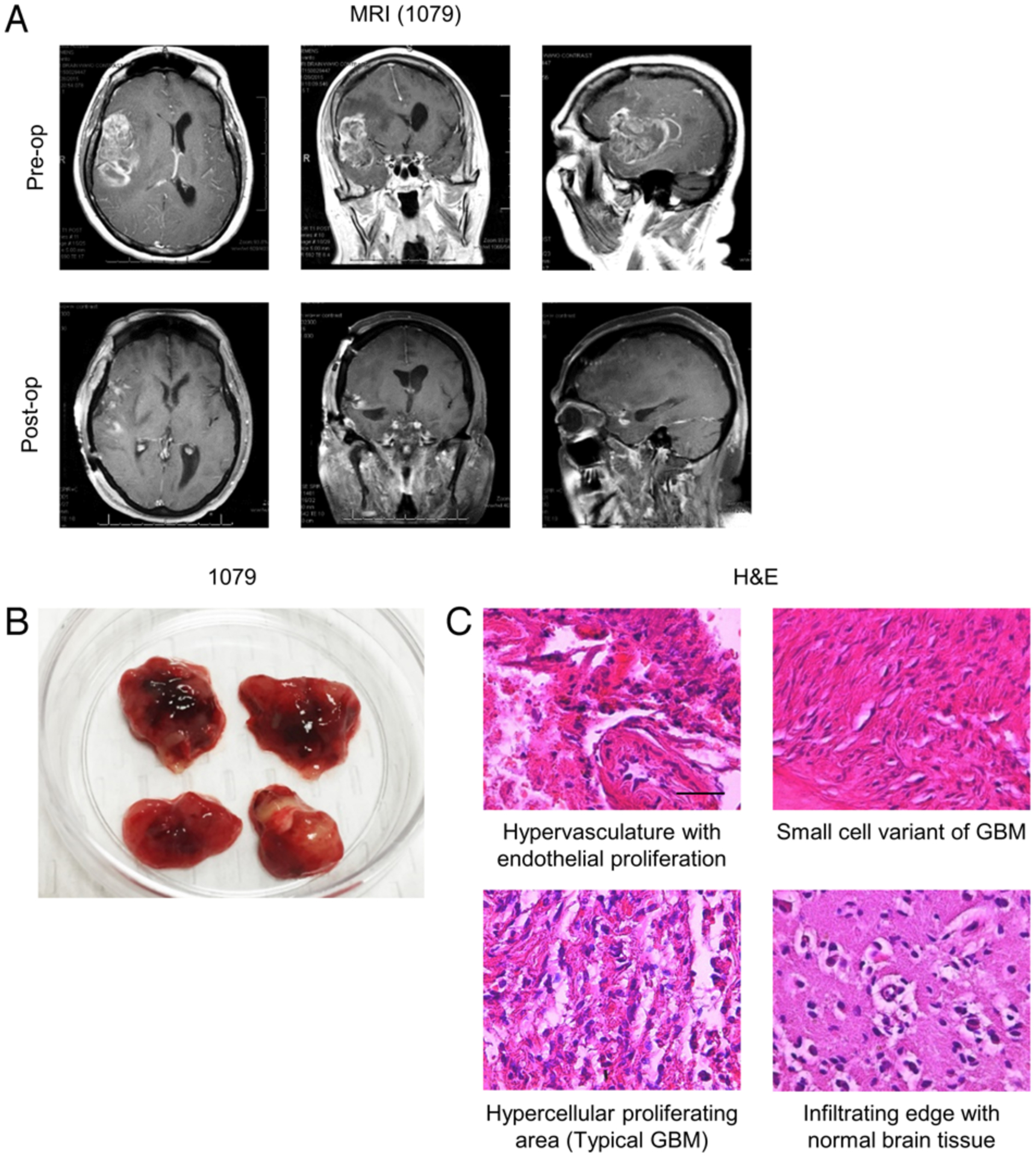

To establish a data analysis pipeline for GBM kinomic analyses, we designed a stepwise procedural approach to identify viable targets through cross-referencing patient-derived tumors with the Ivy GAP,38 functional and validative kinomic analyses, and evaluation of clinical relevance of the established target via pharmacological and genetic inhibition (Fig. 1). During resection, the senior author secured 12 pieces of GBM tumors from an isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) wild-type (IDHWT) primary GBM patient (1079) and an IDH mutant-type (IDHMT) recurrent GBM patient (1076SS; Table 1). Figures 2A and S1A illustrate representative imaging of patients 1079 (right temporoparietal) and 1076SS (left temporoparietal), respectively. Preoperative Gd-enhancing T1-weighted images demonstrated a heterogeneously enhancing solitary lesion with areas of hypointensities, ventricular compression, midline shift, and surrounding edema. Postoperative images displayed total removal of the enhancing lesion with significant resolution of ventricular compression, midline shift, and edema (Fig. 2A). Macroscopically, all tissues looked GBM-like, while some of the tissues appeared to contain some adjacent normal-looking brain tissues (Figs. 2B and S1B). The histopathological evaluation confirmed that both 1079 and 1076SS GBM tumor samples contained the typical characteristics of GBM including endothelial proliferation, small-cell variant, hypercellular proliferation, pseudopallisading with necrosis, and infiltrating edge (Figs. 2C and S1C). These GBM patient tumor samples were processed for kinomic analysis and comparison.

FIG. 1.

Investigative analysis of our running hypothesis. Schematic outlining procedural identification of viable targets, validative analysis, and pharmacological and genetic inhibition for evaluation of clinical relevance. FACS = fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

TABLE 1.

Relevant clinical data for primary and recurrent GBM patients 1079 and 1076SS

| Patient | Age (yrs), Sex | Tumor Location | Type | IDH Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1079 | 59, F | Rt temporal lobe | Primary | Wild-type |

| 1076SS | 38, M | Lt temporal lobe | Recurrent | Mutant |

FIG. 2.

Characterization of GBM patients and surgically derived tumor tissues. A: Preoperative (upper) and postoperative (lower) T1-weighted MR images of patient 1079 depicting a right temporoparietal solitary lesion with heterogeneous Gd+ enhancement in a postcontrast study. Compression on adjacent ventricles with midline shifting and surrounding edema is noted. B: Postresection gross tumor of patient 1079 partitioned into 4 distinct samples. C: H & E staining of tumor samples demonstrating typical GBM features. Bar = 100 μm.

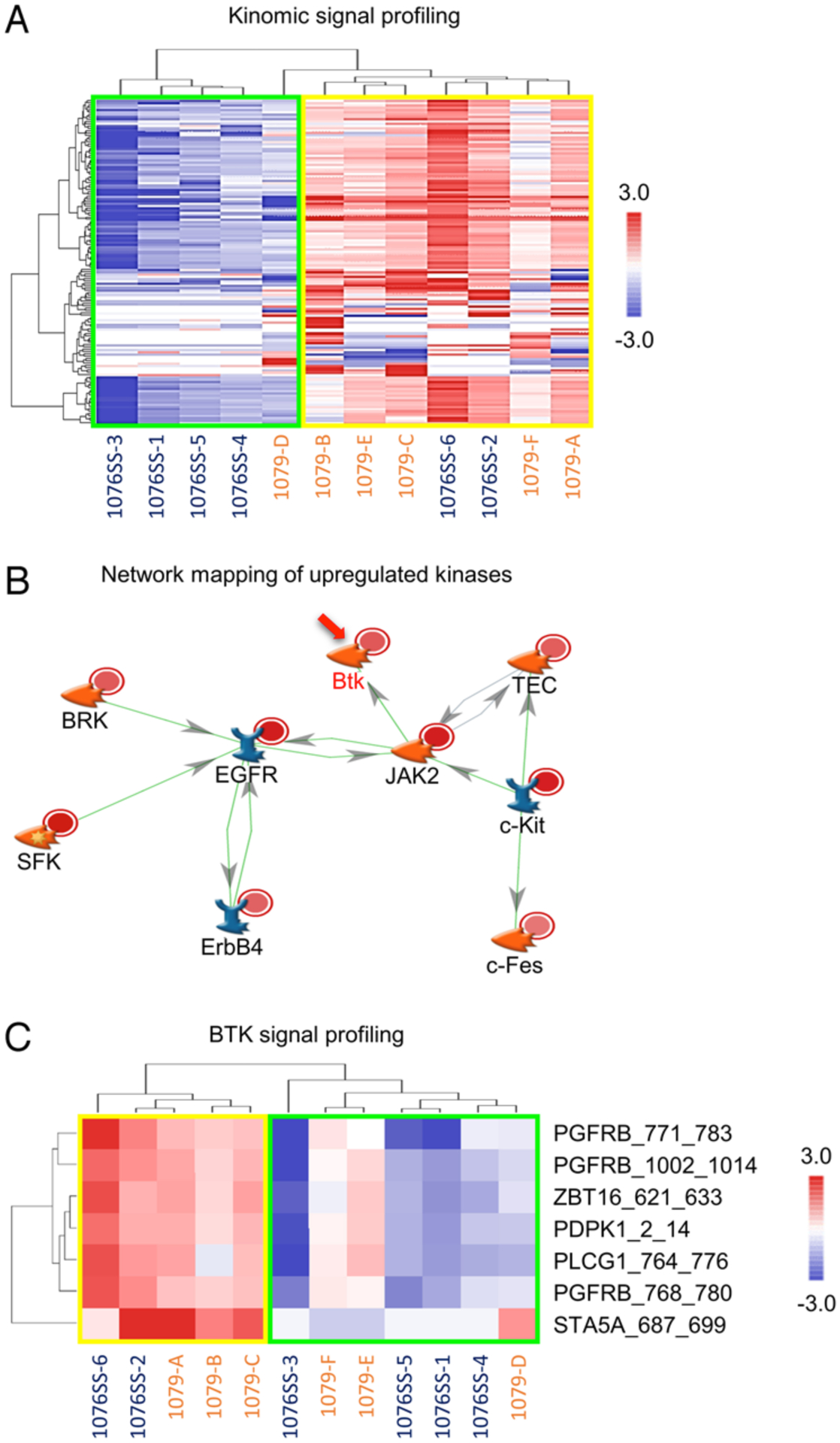

Kinomic Analysis of Protein Tyrosine Kinases Across GBMs

To evaluate kinomic activities of each tumor tissue, we performed protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) kinomic profiling of 1079 and 1076SS tumor tissues using the PamChip multiplex in vitro kinase assay system (Fig. 3A). Signal intensities were then measured for the kinase activities on 144 targetable peptides followed by upstream kinase analysis (UpKin) of the entire array. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering identified two subgroups of tumor tissues (subgroups 1 and 2; Fig. 3A). Of note, both subgroups contained samples from spatially distinct areas, from both tumors, indicating both intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity in kinase activity. Signaling pathway analysis of the UpKin results identified BTK as altered, and as the central node in a pathway altered between the two subgroups (Tables S1 and S2, Figs. S2 and S3). BTK targetable peptides were identified as altered across these two subgroups derived from both 1079 and 1076SS and were network-mapped to a BTK-centric network, which displayed interconnections in multiple kinase downstream activities (Figs. 3B and S3). The target peptides of BTK were preferentially activated in subgroup 2 following the same pattern seen in the profile of the whole array (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these findings indicate significant heterogeneity in kinase activity both within and across distinct GBM tumors, with a potential role for BTK in a subset of tumor cells.

FIG. 3.

Kinomic analysis of PTKs across GBMs. A: Heatmap of 12 spatially distinct GBM tissue samples derived from 2 patients, with an unsupervised hierarchical clustering of kinomic probes (row) per each sample (column), stratified according to kinomic signaling intensity. Red indicates higher phosphorylation while blue indicates lower phosphorylation. B: Upstream kinases of significantly altered peptides in subgroup 2 were mapped to the direct interaction network using MetaCore. The altered kinases of patient 1079 are represented by light red circles and patient 1076SS by dark red circles. Green lines indicate positive interactions and red lines indicate negative interactions, with the direction of interactions annotated with arrows. C: Hierarchically clustered heatmap of BTK target peptides in subgroups 1 and 2. Red indicates higher phosphorylation while blue indicates lower phosphorylation.

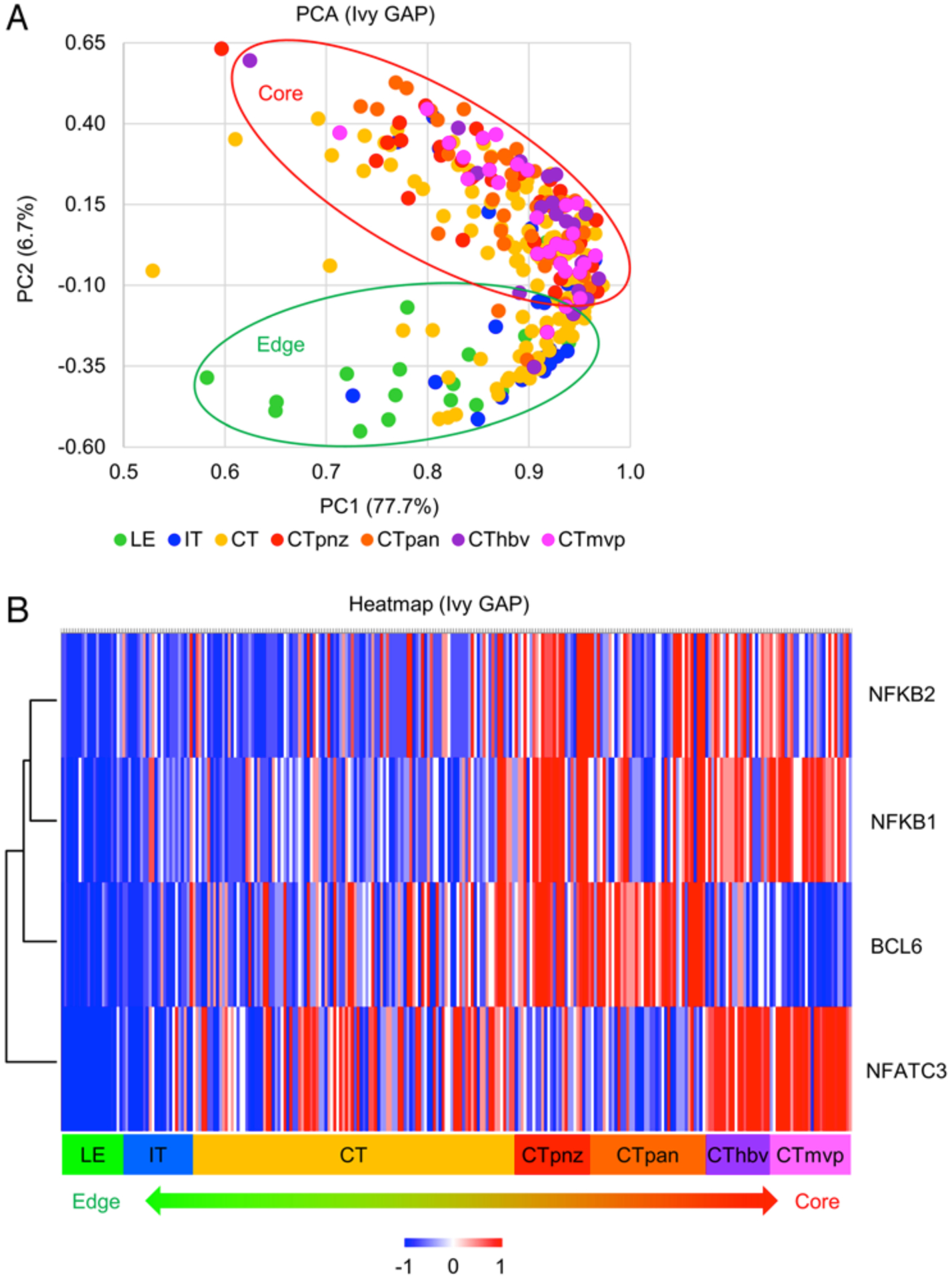

The BTK Pathway and the Tumor Core

One major challenge of the aforementioned data is the lack of spatial information for BTK activity within a single tumor. To address this issue, we utilized the Ivy GAP database38 to identify spatially distinctive gene signatures across GBM regions and validation of BTK’s elevated activity. PCA of RNA-sequencing data for all genes according to spatially distinctive profiles identified the distinct gene signatures of GBM tumor edge (leading edge) and core cells (cellular tumor; Fig. 4A). Because BTK is not transcriptionally regulated and the Ivy GAP database38 is based on RNA-sequencing data, we examined the expression of 4 TFs downstream of the BTK pathway: NFATC3, NF-kB2, BCL6, and NF-kB1. All 4 genes were preferentially upregulated in the tumor core as opposed to the edge (Fig. 4B and S4). These data raised a possibility that activation of BTK resides preferentially in the tumor core, but not in the edge.

FIG. 4.

Stratified clustering of all genes according to regionally distinct origins. A: PCA RNA-sequencing data of all genes in the Ivy GAP38 according to spatially distinctive profiles. A total of 122 RNA samples were generated from 10 GBM tumors. B: Heatmap depicting the spatially distinct expression profile of 4 TFs downstream of the BTK pathway: NFATC3, NF-kB1, NF-kB2, and BCL6. CT = cellular tumor; CThbv = hyperplastic blood vessels in cellular tumor; CTmvp = microvascular proliferation; CTpan = pseudo-palisading cells around necrosis; CTpnz = perinecrotic zone; IT = infiltrating tumor; LE = leading edge; PC1 = principal component 1; PC2 = principal component 2.

GBM Core-Like Cells, Apoptosis, and shRNA-Mediated Genetic Inhibition of BTK

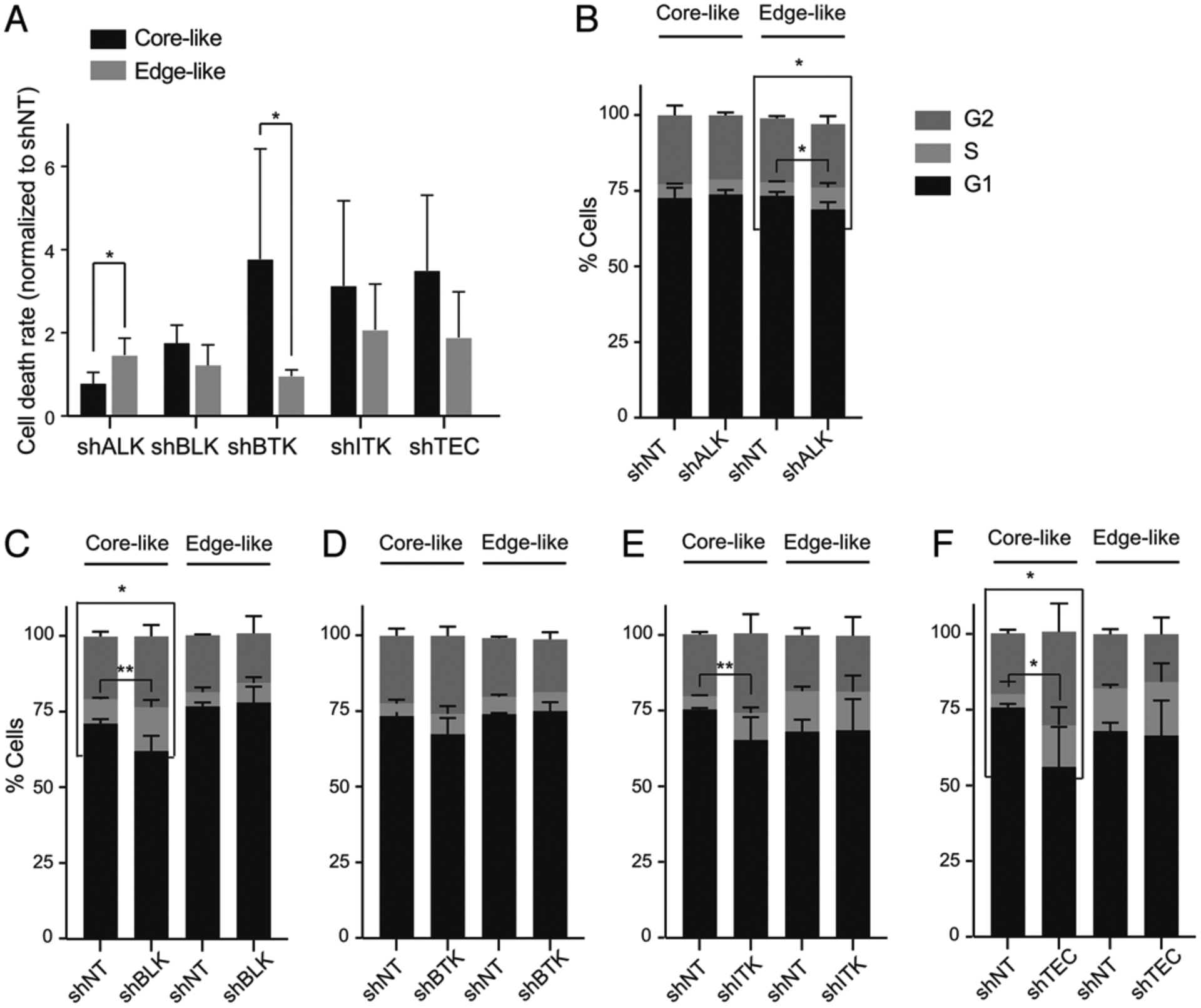

In order to validate the observed kinomic heterogeneity across GBM tumors, we created lentiviral vectors containing shRNA sequences targeting all 5 kinases in the BTK family (TEC, BTK, ITK, BLK, and ALK). These shRNA vectors were infected into our well-characterized tumor core-like and edge-like GBM neurosphere lines.10,11,23,30,35,36,44 Flow cytometry-based cell-cycle analysis was performed to measure the rate of cell death, as well as the proportion of sub-G1 (apoptotic phase) following gene silencing in these tumor cells. Among these 5 genes, BTK silencing was the most effective at promoting apoptosis in the GBM core-like neurospheres compared to their edge-like counterparts (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Target validation through genetic inhibition. A: Flow cytometry–based cell-cycle analysis comparing rate of cell death in edge-like and core-like GBM cells following shRNA silencing of ALK, BLK, BTK, ITK, and TEC. *p < 0.01. B–F: Flow cytometry-based cell-cycle analysis comparing proportion of sub-G1 (apoptotic phase) in edge-like and core-like GBM cells following shRNA silencing of ALK, BLK, BTK, ITK, and TEC. *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001. NT = nontarget.

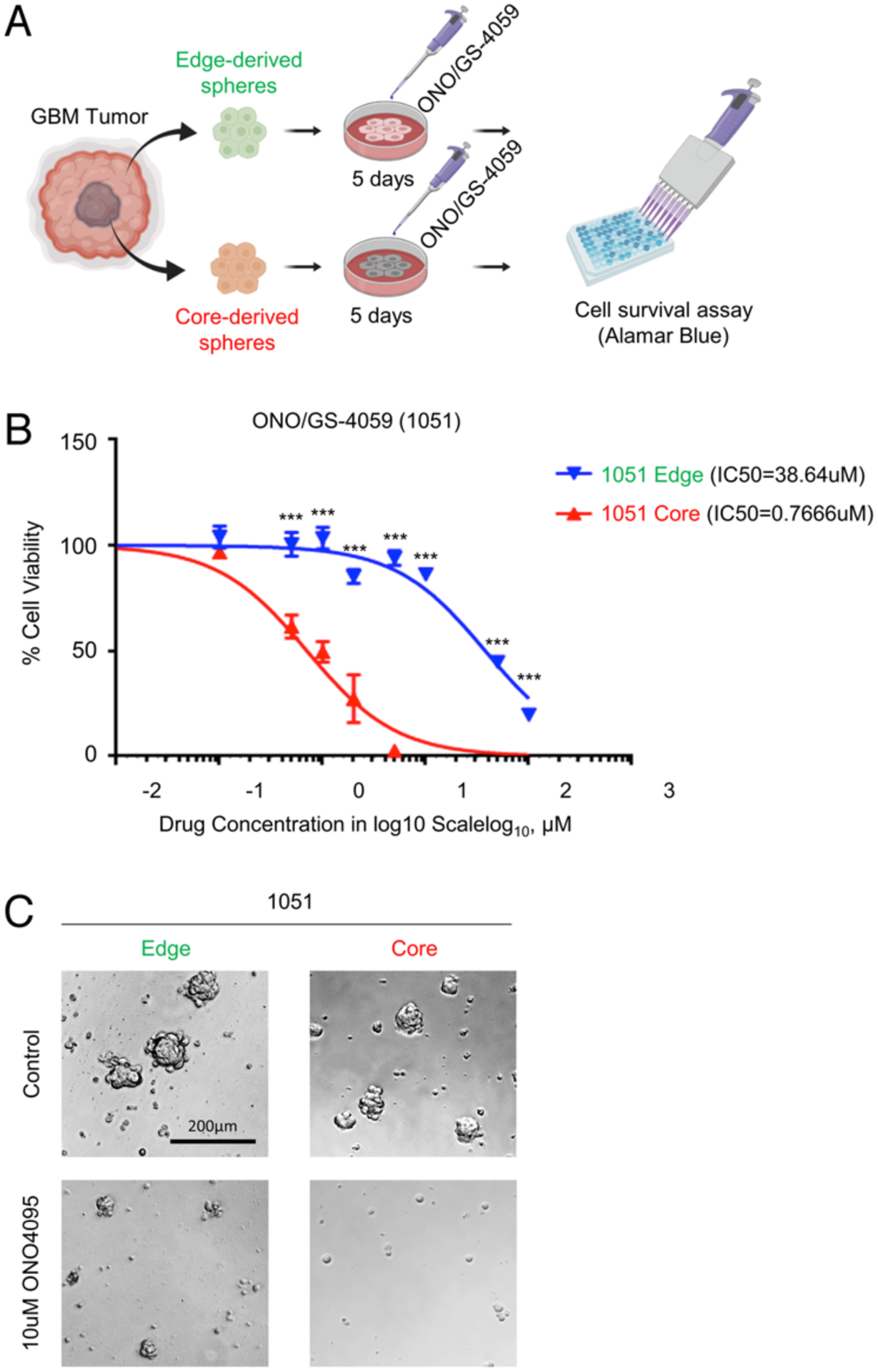

BTK Inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 and Inhibitory Effects on GBM Core Cells

Finally, we sought to explore the clinical relevance of BTK as a therapeutic target for tumor core cells. For this purpose, we established GBM edge- and core-derived neurosphere culture models following neuronavigation-based regional biopsy of 2 primary GBM patients (1051 and 101027;30 Fig. 6A). In vitro sensitivity to the BTK inhibitor, ONO/GS-4059, was compared in these paired cultures (Fig. 6A). As expected, GBM core neurospheres exhibited significantly greater sensitivity to BTK inhibition in comparison to the edge neurospheres in both 1051 neurospheres and, to a lesser extent, 101027 neurospheres (Fig. 6B and C). Collectively, these data suggest BTK inhibition as a viable therapeutic strategy for targeting GBM’s core region.

FIG. 6.

In vitro inhibition of BTK attenuates GBM cellular survival. A: Schematic illustrating in vitro administration of the BTK inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 to GBM-derived tumor neurospheres for 5 days, followed by cell viability assay. Created with BioRender.com. B: In vitro cell viability (alamarBlue) assay comparing 1051 edge and core bulk GBM neurosphere therapeutic responses to ONO/GS-4059, normalized to nontreated control. C: Microscopic images for 1051 edge and core GBM neurospheres before and after ONO/GS-4059 treatment for 5 days, demonstrating decreased core neurosphere growth compared to edge clones.

Discussion

Studying the global kinase activity of tumors provides a unique picture of cellular regulation that would have proven difficult to elucidate from traditional genomic and transcriptomic information.15 By consolidating our focus on the distinctive kinomic profiles of GBM’s intratumoral spatial heterogeneity through combining kinome profiling with Ivy GAP database38 analysis, this study identified the BTK pathway as a possible clinically relevant therapeutic target in GBM. Elevation of BTK activity was attributed to the classically hypoxic and therapy-resistant GBM tumor core, likely in part due to the relative lack of vascular accessibility to this lesion. shRNA-mediated knockdown of BTK in previously established edge- and core-like GBM neurospheres demonstrated an increased apoptotic activity with predominance of the sub-G1 phase of core-like cells. Finally, pharmacological inhibition via administration of ONO/GS-4059 in our regionally derived edge and core GBM neurosphere model demonstrated increased sensitivity of GBM core neurospheres to BTK inhibition.

Protein kinases represent a promising and actionable drug target based on multiple pieces of evidence in various cancer types in recent years.20 Many of the 538 protein kinases encoded by the human genome are known to regulate tumorigenicity and cancer therapy resistance in multiple cancers.27 Since the first protein kinase inhibitor was introduced in the early 1980s, 37 kinase inhibitors have received FDA approval for treatment of malignancies such as breast and lung cancer. Furthermore, approximately 150 kinase-targeted drugs are in different clinical phase trials.5 Among these, 6 tyrosine kinase receptors and their ligands (endothelial growth factor receptor [EGFR], vascular endothelial growth factor, platelet-derived endothelial growth factor [PDGFR], hepatocyte endothelial growth factor/c-MET, fibroblast endothelial growth factor, and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor) were developed as promising therapeutic targets in GBM due to their regulation of downstream signaling pathways associated with tumor cell proliferation, invasiveness, survival, and angiogenesis.37 Tyrosine kinase receptors share a similar structure wherein their activation via ligand binding results in receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase domain, thereby activating two prominent downstream signaling pathways: Ras/MAPK/ERK and Ras/PI3K/AKT.22,28 Prominent genetic aberrations in GBM, such as EGFR, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, PTEN, TP53, and CDKN2A/B, drive the dysfunction of the three major signaling pathways PI3K/Akt/mTOR, p53, and RB1.7 Despite substantial efforts invested in the development of novel selective inhibitors targeting these pathways, many factors confounded the clinical efficacy of these molecules.53 As expanded upon in this study, spatial heterogeneity represents one such obstacle, wherein inconsistent drug delivery to distinct regions of GBM tumors can also contribute to the unsatisfactory therapeutic response and allows for evolutionary selection of therapy-resistant strains and/or therapy-induced secondary alterations to develop therapy-resistant tumor cells. Our approach takes into consideration the distinct regional profiles of GBM, and in doing so, a core-specific role was determined for BTK activity. While further refinement of the platform employed in this study may be achieved via standardizing the affinity of phosphospecific antibodies to specific substrates and establishing a more developed bioinformatical framework of this approach, its utilization for molecular analyses should enable further discovery of clinically relevant actionable molecules as therapeutic targets in GBM due to its high-throughput format and stability.

In a recent study aiming to evaluate the clinical relevance of BTK expression in glioma patients, Yue et al. demonstrated that elevated expression of BTK is associated with poorer patient survival.55 They additionally suggested that BTK inhibition via ibrutinib significantly blocks the degradation of IκBα and prevents nuclear accumulation of the NF-κB p65 subunit induced by EGF in glioma cells.41 Another study by Wang et al. provided pieces of experimental evidence to suggest that ibrutinib exerts a profound antitumor effect and induces autophagy through the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in GBM cells.50 However, given the nonspecificity of ibrutinib,9,47 which targets several other kinases,9,49 concerns remain as to the specificity of therapeutic response as well as its potential toxicity profile.13,29 To add another layer of complexity to the trending association of BTK with GBM tumorigenesis, researchers at Cleveland Clinic recently reported that BTK expression was hardly detected in glioma stem cells, and that the BTK inhibitor response was conferred via inhibition of another nonreceptor tyrosine kinase (BMX), not due to direct BTK inhibition.43 In the present study, not only was BTK significantly activated in the tumor core, but selective targeting via ONO/GS-4059 (an irreversible BTK inhibitor) led to elevated apoptotic activity in GBM cells. Given the BTK family’s fully elucidated role in B-cell development and maturation,25,26,32,42 ONO/GS-4059 was predictably used in a phase 1 clinical trial of relapsed and refractory mature B-cell malignancies (clinicaltrials.gov no.: NCT01659255) with some promising results.48 In GBM, targeting BTK in this manner may address the non-selectivity concerns surrounding ibrutinib and may result in a better clinical profile, as the tumor core appears to contain therapy-resistant tumor cell populations.30

One important piece of data we found is that in both cases, we identified two, but not more, distinct subgroups. It is predictable that intratumorally, GBM tumors have at least two subgroups that are sensitive and resistant to BTK inhibition. Theoretically, clinical trials for GBM using BTK inhibition should combine some other treatment regimen to eliminate the other subgroup. Additionally, we did see intertumoral difference in the kinomic activities between multiple tumor tissues. It is not surprising given the difference of these two patient tumors (i.e., IDH status, naïve vs recurrent tumor, etc.). Nonetheless, one piece of the important findings is that intratumoral kinomic heterogeneity is, at least to some extent, shared between these two WHO grade IV GBM tumors. We believe that it is indicative of, if not directly proving, the molecular complexity in GBM regardless of the genetic background and prior treatment. However, given this limitation, future investigations would benefit from increased availability of IDHWT and IDHMT tumor samples.

Further assessment of therapeutic benefit will be sought in future studies employing regionally specified xenograft murine in vivo models, which may serve to correlate BTK inhibition with prolonged survival. Additionally, confirmation of BTK’s elevated activity utilizing more regionally derived GBM tumors may be necessary. Finally, characterization of the molecular mechanisms governing BTK pathway activity in GBM may elucidate new therapeutic targets and will require further investigation.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated elevated activity of BTK in GBM with distinct spatial profiling in GBM’s infiltrating edge and core cell populations; additionally, we determined clinicopathological significance attributable to BTK activity in the GBM core. Collectively, our findings indicate that selective inhibition of BTK may prove highly beneficial as an adjuvant to chemoradiotherapy following resection due to potential suppression of GBM recurrence via inhibition of tumor core redevelopment. Given that this study identified significant kinomic inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity, our findings may guide new investigative and therapeutic approaches toward various solid carcinomas beyond GBM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the Nakano laboratory members for their hard work, discussion, and constructive feedback. This study was supported by NIH grant nos. R01NS083767, R01NS087913, R01CA183991, and R01CA201402 to Dr. Nakano.

ABBREVIATIONS

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

endothelial growth factor receptor

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GAP

Glioblastoma Atlas Project

- GBM

glioblastoma

- GSC

glioma stemlike cell

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- MCL

mantle cell lymphoma

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PDGFR

platelet-derived endothelial growth factor

- PI

propidium iodide

- PTK

protein tyrosine kinase

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TF

transcription factor

- UAB

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Supplemental Information

Online-Only Content

Supplemental material is available with the online version of the article.

Figures S1–S5 and Tables S1 and S2. https://thejns.org/doi/suppl/10.3171/2019.7.JNS191376.

References

- 1.Anderson JC, Duarte CW, Welaya K, Rohrbach TD, Bredel M, Yang ES, et al. : Kinomic exploration of temozolomide and radiation resistance in Glioblastoma multiforme xenolines. Radiother Oncol 111:468–474, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JC, Minnich DJ, Dobelbower MC, Denton AJ, Dussaq AM, Gilbert AN, et al. : Kinomic profiling of electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy specimens: a new approach for personalized medicine. PLoS One 9:e116388, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arsenault R, Griebel P, Napper S: Peptide arrays for kinome analysis: new opportunities and remaining challenges. Proteomics 11:4595–4609, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bam R, Venkateshaiah SU, Khan S, Ling W, Randal SS, Li X, et al. : Role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) in growth and metastasis of INA6 myeloma cells. Blood Cancer J 4:e234, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhullar KS, Lagarón NO, McGowan EM, Parmar I, Jha A, Hubbard BP, et al. : Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: progress, challenges and future directions. Mol Cancer 17:48, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T: Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature 411:355–365, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, et al. : The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155:462–477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum KA, et al. : Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 369:32–42, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Kinoshita T, Sukbuntherng J, Chang BY, Elias L: Ibrutinib inhibits ERBB receptor tyrosine kinases and HER2-amplified breast cancer cell growth. Mol Cancer Ther 15:2835–2844, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng P, Phillips E, Kim SH, Taylor D, Hielscher T, Puccio L, et al. : Kinome-wide shRNA screen identifies the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL as a key regulator for mesenchymal glioblastoma stem-like cells. Stem Cell Reports 4:899–913, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darmanis S, Sloan SA, Croote D, Mignardi M, Chernikova S, Samghababi P, et al. : Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of infiltrating neoplastic cells at the migrating front of human glioblastoma. Cell Rep 21:1399–1410, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Cruz OJ, Uckun FM: Novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors currently in development. OncoTargets Ther 6:161–176, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Weerdt I, Koopmans SM, Kater AP, van Gelder M: Incidence and management of toxicity associated with ibrutinib and idelalisib: a practical approach. Haematologica 102:1629–1639, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding SJ, Qian WJ, Smith RD: Quantitative proteomic approaches for studying phosphotyrosine signaling. Expert Rev Proteomics 4:13–23, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dussaq AM, Kennell T Jr, Eustace NJ, Anderson JC, Almeida JS, Willey CD: Kinomics toolbox—A web platform for analysis and viewing of kinomic peptide array data. PLoS One 13:e0202139, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Easwaran H, Tsai HC, Baylin SB: Cancer epigenetics: tumor heterogeneity, plasticity of stem-like states, and drug resistance. Mol Cell 54:716–727, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert AN, Shevin RS, Anderson JC, Langford CP, Eustace N, Gillespie GY, et al. : Generation of microtumors using 3D human biogel culture system and patient-derived glioblastoma cells for kinomic profiling and drug response testing. J Vis Exp (112):54026, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goidts V, Bageritz J, Puccio L, Nakata S, Zapatka M, Barbus S, et al. : RNAi screening in glioma stem-like cells identifies PFKFB4 as a key molecule important for cancer cell survival. Oncogene 31:3235–3243, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardwick JC, van Santen M, van den Brink GR, van Deventer SJ, Peppelenbosch MP: DNA array analysis of the effects of aspirin on colon cancer cells: involvement of Rac1. Carcinogenesis 25:1293–1298, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser AS, Chavali S, Masuho I, Jahn LJ, Martemyanov KA, Gloriam DE, et al. : Pharmacogenomics of GPCR drug targets. Cell 172:41–54, 54.e1–54.e19, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson G, Bradley M: Functional peptide arrays for high-throughput chemical biology based applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol 18:326–330, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubbard SR, Miller WT: Receptor tyrosine kinases: mechanisms of activation and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19:117–123, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin X, Kim LJY, Wu Q, Wallace LC, Prager BC, Sanvoranart T, et al. : Targeting glioma stem cells through combined BMI1 and EZH2 inhibition. Nat Med 23:1352–1361, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs EG: Nobel Lecture. Protein phosphorylation and cellular regulation I. Biosci Rep 13:127–142, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Herrera G, Vargas-Hernández A, González-Serrano ME, Berrón-Ruiz L, Rodríguez-Alba JC, Espinosa-Rosales F, et al. : Bruton’s tyrosine kinase—an integral protein of B cell development that also has an essential role in the innate immune system. J Leukoc Biol 95:243–250, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maas A, Hendriks RW: Role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cell development. Dev Immunol 8:171–181, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S: The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298:1912–1934, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maruyama IN: Mechanisms of activation of receptor tyrosine kinases: monomers or dimers. Cells 3:304–330, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mato AR, Nabhan C, Thompson MC, Lamanna N, Brander DM, Hill B, et al. : Toxicities and outcomes of 616 ibrutinib-treated patients in the United States: a real-world analysis. Haematologica 103:874–879, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minata M, Audia A, Shi J, Lu S, Bernstock J, Pavlyukov MS, et al. : Phenotypic plasticity of invasive edge glioma stem-like cells in response to ionizing radiation. Cell Rep 26:1893–1905, 1905.e1–1905.e7, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olar A, Aldape KD: Using the molecular classification of glioblastoma to inform personalized treatment. J Pathol 232:165–177, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pal Singh S, Dammeijer F, Hendriks RW: Role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cells and malignancies. Mol Cancer 17:57, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parikh K, Peppelenbosch MP: Kinome profiling of clinical cancer specimens. Cancer Res 70:2575–2578, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parikh K, Peppelenbosch MP, Ritsema T: Kinome profiling using peptide arrays in eukaryotic cells. Methods Mol Biol 527:269–280, x, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel AP, Tirosh I, Trombetta JJ, Shalek AK, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, et al. : Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344:1396–1401, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pavlyukov MS, Yu H, Bastola S, Minata M, Shender VO, Lee Y, et al. : Apoptotic cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote malignancy of glioblastoma via intercellular transfer of splicing factors. Cancer Cell 34:119–135 e110, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson JRD, Regad T: Targeting cellular pathways in glioblastoma multiforme. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2:17040, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puchalski RB, Shah N, Miller J, Dalley R, Nomura SR, Yoon JG, et al. : An anatomic transcriptional atlas of human glioblastoma. Science 360:660–663, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Queiroz KC, Tio RA, Zeebregts CJ, Bijlsma MF, Zijlstra F, Badlou B, et al. : Human plasma very low density lipoprotein carries Indian hedgehog. J Proteome Res 9:6052–6059, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rawlings DJ, Witte ON: The Btk subfamily of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases: structure, regulation and function. Semin Immunol 7:237–246, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sagiv-Barfi I, Kohrt HE, Czerwinski DK, Ng PP, Chang BY, Levy R: Therapeutic antitumor immunity by checkpoint blockade is enhanced by ibrutinib, an inhibitor of both BTK and ITK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E966–E972, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satterthwaite AB, Witte ON: The role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B-cell development and function: a genetic perspective. Immunol Rev 175:120–127, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Y, Guryanova OA, Zhou W, Liu C, Huang Z, Fang X, et al. : Ibrutinib inactivates BMX-STAT3 in glioma stem cells to impair malignant growth and radioresistance. Sci Transl Med 10(443):eaa6816, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SG, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, et al. : Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:4009–4014, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. : Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 10:459–466, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thakkar JP, Dolecek TA, Horbinski C, Ostrom QT, Lightner DD, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. : Epidemiologic and molecular prognostic review of glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Bio-markers Prev 23:1985–1996, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tucker DL, Rule SA: A critical appraisal of ibrutinib in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag 11:979–990, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter HS, Rule SA, Dyer MJ, Karlin L, Jones C, Cazin B, et al. : A phase 1 clinical trial of the selective BTK inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 in relapsed and refractory mature B-cell malignancies. Blood 127:411–419, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang A, Yan XE, Wu H, Wang W, Hu C, Chen C, et al. : Ibrutinib targets mutant-EGFR kinase with a distinct binding conformation. Oncotarget 7:69760–69769, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Liu X, Hong Y, Wang S, Chen P, Gu A, et al. : Ibrutinib, a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, exhibits antitumoral activity and induces autophagy in glioblastoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 36:96, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, Goy A, Auer R, Kahl BS, et al. : Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 369:507–516, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wei L, Su YK, Lin CM, Chao TY, Huang SP, Huynh TT, et al. : Preclinical investigation of ibrutinib, a Bruton’s kinase tyrosine (Btk) inhibitor, in suppressing glioma tumorigenesis and stem cell phenotypes. Oncotarget 7:69961–69975, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westphal M, Maire CL, Lamszus K: EGFR as a target for glioblastoma treatment: an unfulfilled promise. CNS Drugs 31:723–735, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiao GG, Recker RR, Deng HW: Recent advances in proteomics and cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Med Oncol 2:63–72, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yue C, Niu M, Shan QQ, Zhou T, Tu Y, Xie P, et al. : High expression of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is required for EGFR-induced NF-κB activation and predicts poor prognosis in human glioma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 36:132, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.