Abstract

Bruton's agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase (BTK) is an important cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase involved in B-lymphocyte development, differentiation, and signaling. Activated protein kinase C (PKC), in turn, induces the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, which promotes cell proliferation, viability, apoptosis, and metastasis. This effect is associated with nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation, suggesting an anti-metastatic effect of BTK inhibitors on MCF-7 cells that leads to the downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression. However, the effect of BTK on breast cancer metastasis is unknown. In this study, the anti-metastatic activity of BTK inhibitors was examined in MCF-7 cells focusing on MMP-9 expression in 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-stimulated MCF-7 cells. The expression and activity of MMP-9 in MCF-7 cells were investigated using quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis, western blotting, and zymography. Cell invasion and migration were investigated using the Matrigel invasion and cell migration assays. BTK inhibitors [ibrutinib (10 µM), CNX-774 (10 µM)] significantly attenuated TPA-induced cell invasion and migration in MCF-7 cells and inhibited the activation of the phospholipase Cγ2/PKCβ signaling pathways. In addition, small interfering RNA specific for BTK suppressed MMP-9 expression and cell metastasis. Collectively, results of the present study indicated that BTK suppressed TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and cell invasion/migration by activating the MAPK or IκB kinase/NF-κB/activator protein-1 pathway. The results clarify the mechanism of action of BTK in cancer cell metastasis by regulating MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells.

Keywords: Bruton's agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase, matrix metalloproteinase-9, protein kinase C, MCF-7 cells, neoplasm invasiveness

Introduction

Breast cancer, a primary cause of female mortality (1–3), is characterized by a high mortality rate owing to the invasive and metastatic potential of cancer cells (4). In 2018 worldwide, the incidence of breast cancer was 24.2%, and the invasive cancer rate was 11.6% in woman cancer patents (2). Furthermore, in Korea in 2017, the incidence of breast cancer was 20.3%, and the invasive cancer rate was 15.6% in woman cancer patents (3). One of the primary therapeutic approaches against breast cancer metastasis involves the development of effective anti-invasive agents (5,6). Cancer cell invasion, induced by extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, initiates the metastatic process; the cancer cells find their way through adjacent tissues, invade blood vessels, and move along the vessel walls to migrate to other organs (7,8). ECM degradation is caused by various extracellular proteases, of which matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a crucial role in breast cancer (7,8).

Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a member of the Tec family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases in the B-cell receptor signaling pathway and a driving force for CLL and other B-cell malignancies (9–12). BTK, a multidomain protein, can interact with and activate other molecules, including phospholipase C (PLC) γ2 (13–15). PLCγ2, a member of phosphoinositide-specific PLCs, enhances the activation of protein kinase C (PKC) by catalyzing the degradation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). IP3 induces the elevation of intracellular calcium levels (16). Activated PKC, in turn, induces the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, which promotes cell proliferation, viability, apoptosis, and metastasis (17,18). Previous research on BTK in breast cancer cells has mainly focused on its role in the regulation of cell viability (19,20). The effects of BTK on the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells and its signaling mechanism remain unclear.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that can be divided into six subclasses: Collagenases, stromelysins, gelatinases, matrilysins, membrane-associated MMPs, and other MMPs (21). MMP-9 has been identified as a crucial MMP involved in cancer cell invasion, and it is directly linked to the induction of cancer cell metastasis and poor prognosis in cancer patients (22,23). MMP-9 expression is induced by various stimuli, including cytokines, growth factors, and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (24–27). In particular, TPA significantly stimulates MMP synthesis and secretion by activating PKC (28–30). TPA-induced MMP-9 expression is triggered by the activation of transcription factors, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) (31,32). NF-κB and AP-1 play pivotal roles in TPA-induced MMP-9 expression in breast cancer cell metastasis and are regulated by MAPKs (33–35). The signaling pathways mediated by MAPKs activate IκB kinase (IKK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), or p38 MAPK, depending on the cell type (24,36–38). Findings of those studies highlight the potential importance of suppressing MMP-9 expression or its upstream regulatory pathways for the treatment of metastasis in breast cancer.

In this study, we investigated the regulatory effects of BTK inhibitors on PKC-mediated MMP-9 expression and invasion in MCF-7 cells. Our data demonstrated that BTK inhibitors suppressed TPA-induced MMP-9 expression by blocking MAPK/NF-κB/AP-1 signal transduction via the PLCγ2/PKC pathway. Thus, the data confirmed that BTK inhibitors suppress MCF-7 cell metastasis by regulating MMP-9 expression.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture

MCF-7 human breast cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (cat. no. HTB-22). MCF-7 cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; WelGENE Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies; cat. no. 160000-044) and 1% antibiotics (anti-anti). Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Reagents

The BTK inhibitor, ibrutinib was purchased from Wuhan NCE Biomedical Co., Ltd., while CNX-774 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals. TPA (P1585) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; cat. no. 472301) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Matrigel was obtained from Corning Inc. (cat. no. 356234). Before cell treatment, each reagent was dissolved in DMSO.

Measurement of cell viability

The viability of MCF-7 cells was assessed as previously described (39). Cell viability was analyzed using the EZ-Cytox reagent Cell Viability Assay Kit (DoGen) following the manufacturer's instructions. MCF-7 cells (3×104) well were seeded onto 96-well plates, treated with the indicated concentrations of BTK inhibitors, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 24 h, EZ-cytox reagent solution (10 µl) was added to each well of the 96-well plate, and the cells were further incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Sunrise™ ELISA reader (Tecan). The optical density of the control was considered 100%.

Western blot analysis

MCF-7 cells (7×105) were pretreated with 10 µM of either of the two BTK inhibitors for 1 h and then incubated with TPA for 24 h at 37°C. Total protein was extracted using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Calbiochem), as previously described (39). The lysates were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the protein concentrations in the lysates were assessed using a BioSpec-nano device (Shimadzu). Equal quantities of protein (10 µg) were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Hybond™ polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) using a western blot apparatus. Each membrane was blocked for 2 h with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 5% skim milk in TTBS with Tween-20, and the blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (1:2,500 dilution); anti-β-actin antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Primary antibodies (1:2,500 dilution) against the following antigens were used: p38 (cat. no. 9212), JNK (cat. no. 9252), ERK (cat. no. 9102), IKKα (cat. no. 2682) and IKKβ (cat. no. 2678), phosphorylated forms of p38 (cat. no. 9211), JNK (cat. no. 9251), and ERK (cat. no. 9101); c-Jun (cat. no. 9261); inhibitory subunit of NF-κBα (IκBα; cat. no. 2859); IKKαβ (cat. no. 2697); and PLCγ2 (cat. no. 3874). These were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly). Polyclonal antibodies (1:2,500 dilution) against p50 (SC-7178), p65 (SC-372), MMP-9 (SC-12759), IκBα (SC-371), PLC γ2 (SC-5283) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Antibodies (1:2,500 dilution) against PKCα (ab32376), PKCβ (ab32026), and PKCδ (ab182126) were purchased from Abcam. The blots were washed in TBS with 0.2% Tween-20 (TBST) and secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (cat. no. sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or anti-rabbit (cat. no. sc-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) antibody (1:2,500 dilution) at 4°C for 1 h. The protein bands were detected by HRP Substrate Luminol Reagent (EMD Millipore Corporation), and protein expression levels were determined using a Mini HD6 image analyzer (UVItec). The blot was re-probed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading.

Gelatin zymography analysis

MMP-9 activity was measured by gelatin zymography, as previously described previously (39). MCF-7 cells (7×105) were pretreated with either of the two BTK inhibitors (10 µM) in serum-free medium for 1 h and then incubated with TPA (20 µM) for 24 h at 37°C. The conditioned medium was collected after 24 h of stimulation, cleared by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 4 min at 4°C, mixed with non-reducing sample buffer, and electrophoresed on a polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% (w/v) gelatin. Following electrophoresis, the gel was washed at room temperature for 30 min with 2.5% Triton X-100, followed by incubation at 37°C for 16 h in 5 mM CaCl2, 0.02% Brij-35, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Finally, the gels were stained with 0.25% (w/v) Coomassie Brilliant Blue in 40% (v/v) methanol and 7% (v/v) acetic acid. Proteolysis was detected as a white zone in a dark blue field using a digital imaging system (Cell Biosciences).

RNA isolation and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

This method was performed as previously described (39). Total RNA was isolated from MCF-7 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA (1 µg) was synthesized using a High Capacity cDNA synthesis kit from PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara). mRNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR analysis using the StepOnePlus™ Real-time PCR System and SYBR-Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The PCR cycling conditions were: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The primers used were: MMP-9 (NM 004994), 5-CCTGGAGACCTGAGAACCAATCT-3 (forward), 5-CCACCCGAGTGTAACCATAGC-3 (reverse); and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; NM 002046), 5-ATGGAAATCCCATCACCATCTT-3 (forward), and 5-CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGG-3 (reverse). Gene expression data were normalized to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Relative quantitation was performed using the comparative ∆∆Ct method according to the manufacturer's instructions (40).

Preparation of nuclear extracts

This method was performed as previously described (39). MCF-7 cells (2×106) were treated with either BTK inhibitor and then incubated with TPA for 3 h at 37°C. The cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in 1.5 ml ice-cold PBS (pH 7.5), and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 4 min at 4°C. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Membrane fractionation

MCF-7 cells (5×107) were treated with 10 µM of either BTK inhibitor for 1 h and then incubated with TPA for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were immediately washed twice, scraped in 1.5 ml of ice-cold PBS (pH 7.5), and pelleted at 300 × g for 3 min at 4°C. After incubation on ice for 30 min, the cells were lysed in homogenization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors; pH 7.5) with brief sonication (5 times for 10 sec, each at 10% amplitude). The resulting cell lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to separate the soluble (cytosolic) and pellet (membrane) fractions. The pellet was resuspended in solubilization buffer and incubated on ice for 30 min. The suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then collected as the membrane fraction.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

MCF-7 cells (1×105) were seeded onto 24-well plates. Cells were transfected with NF-κB or AP-1 reporter and Renilla luciferase thymidine kinase reporter vector were co-transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at 70–80% confluency. The transfected cells were pretreated with either BTK inhibitor at the indicated concentration for 1 h and then treated with 100 nM TPA at 37°C. Whole-cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and Lumat LB 9507 luminometer (EG&G Berthold). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized against Renilla luciferase activity.

Matrigel invasion and migration assays

This method was performed as previously described (39). The invasion assay was carried out in 24-well chambers (8-µm pore size) coated with 20 µl Matrigel (diluted in DMEM). The Matrigel coating was rehydrated in 0.5 ml DMEM for 30 min immediately before the experiments. The migration assay was performed using an insert (8-µm pore size) in 24-well chambers without Matrigel coating. Cells (3×105) were added to the upper chamber, and TPA, alone or with 10 µM of either BTK inhibitor was added to the bottom well. Additionally, cells (2×105) transfected with BTK small-interfering RNA (siRNA) were added to the upper chamber, and TPA was added to the bottom well. The chambers were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 24-h incubation, the cells on the upper surface of the chamber were removed with cotton swabs, and cells that had migrated were fixed and stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 30 min at room temperature and rinsed with water to remove any unbound dye. The membranes were dried, and invading cells were counted in five random areas of the membrane under a light microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM from three in experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with Scheffe post hoc test (SAS software, version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc.). Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Inhibition of BTK expression attenuates TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and secretion in MCF-7 cells

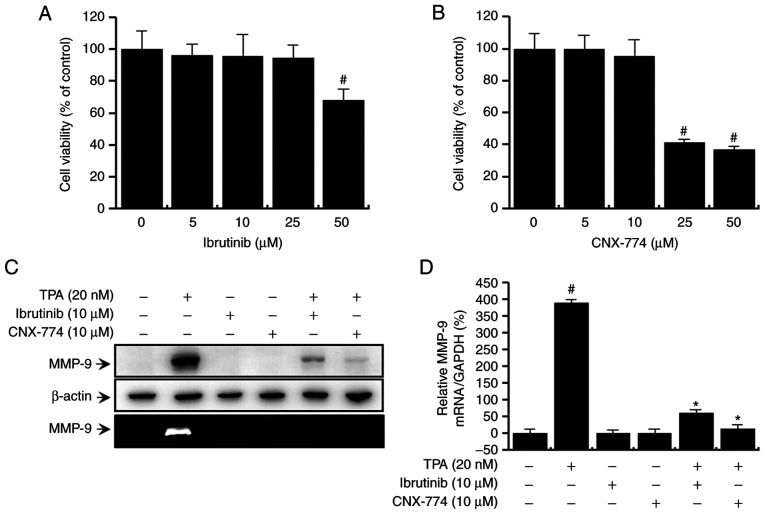

First, we evaluated the potential cytotoxic effects of the BTK inhibitors, ibrutinib and CNX-774, on MCF-7 cells. The inhibitors did not affect cell viability (Fig. 1A and B) or morphology at the experimental concentrations used (≤50 µM). Therefore, we chose the optimal non-toxic concentration (10 µM) of the BTK inhibitors for subsequent experiments. Next, to validate the effects of BTK on TPA-induced MMP-9 expression, we performed quantitative PCR analysis, western blot analysis, and zymography. Western blot analysis revealed that treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 suppressed the TPA-induced upregulation of MMP-9 expression (Fig. 1C, upper panel). Quantitative PCR also confirmed that a TPA-induced increase in MMP-9 mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells was suppressed after treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 (Fig. 1D). The degree of TPA-induced exocytosis of MMP-9 was assessed by zymography, which revealed that treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 significantly reduced TPA-induced MMP-9 secretion (Fig. 1C, lower panel). Overall, these findings show that the inhibition of BTK expression suppresses TPA-induced MMP-9 mRNA and protein expression while simultaneously suppressing MMP-9 enzymatic activation.

Figure 1.

Effect of BTK inhibitors on the MCF-7 cells by TPA-induced MMP-9 expression. To examine the cytotoxicity of BTK inhibitors, cells were cultured in 96-well plates to 70% confluency and various concentrations of (A) ibrutinib or (B) CNX-774 were added to the cell culture and incubated for 24 h. The EZ-Cytox Enhanced Cell Viability Assay Kit was used to determine cell viability. The optical density of the control was considered 100%. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P<0.05 compared with 0 µM of BTK inhibitors at 24 h. MCF-7 cells were treated with BTK inhibitors in the presence or absence of TPA for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using an anti-MMP-9 antibody. The blot was re-probed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. Conditioned medium was prepared and used for gelatin zymography (C). MMP-9 mRNA levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR and GAPDH was used as an internal control Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P<0.01 vs. untreated control; *P<0.01 vs. TPA. (D) The blot was re-probed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading.

Inhibition of BTK expression regulates PLC signaling in MCF-7 cells

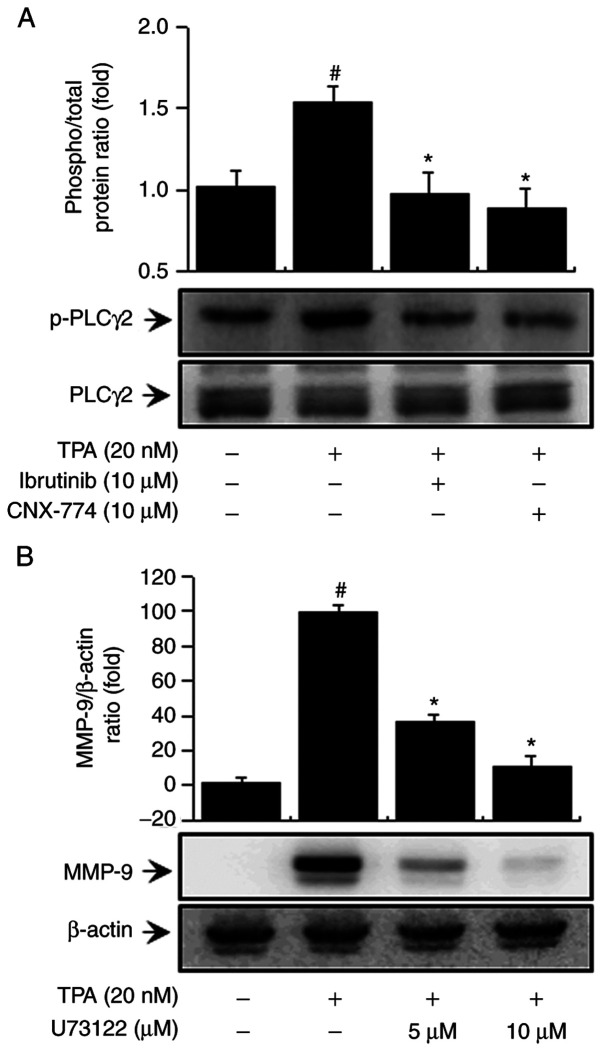

BTK reportedly regulates the activation of PLCγ2 (13,15). We examined the influence of BTK on PLC signaling regulation. First, to determine the effects of BTK inhibitors on PLCγ2 activation in MCF-7 cells, we verified PLCγ2 phosphorylation and confirmed that treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 suppressed PLCγ2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). In addition, to validate the regulatory effects of PLC on MMP-9 expression, we treated the cells with U-73122, a PLC inhibitor, and confirmed that it suppressed MMP-9 expression (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that PLCγ2 regulates MMP-9 expression by inhibiting BTK expression in MCF-7 cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of BTK inhibitors on TPA-induced intracellular signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. The cells were pretreated with BTK inhibitors for 1 h and then stimulated with TPA. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using anti-p-PLCγ2 and anti-PLC γ2 antibodies (A). MCF-7 cells were pretreated with PLC inhibitors for 1 h and then stimulated with TPA. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting using an anti-MMP-9 antibody (B). Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P<0.01 vs. untreated control; *P<0.01 vs. TPA. The blot was reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading.

Inhibition of BTK expression regulates the TPA-induced PKC/MAPK/IKK signaling pathway in MCF-7 cells

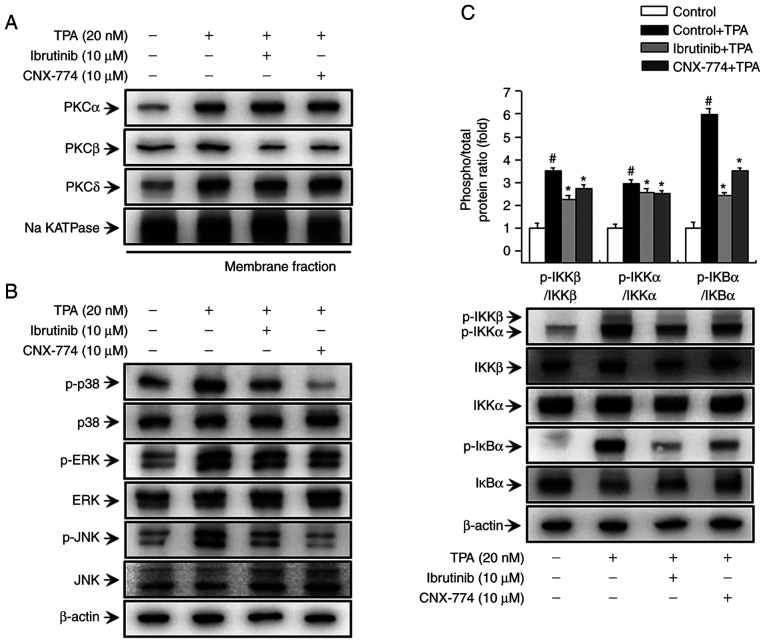

In previous studies, we have demonstrated that PKC is involved in TPA-induced MMP-9 expression via MAPK and IKK signaling (31,32). In the current study, we aimed to validate the effects of BTK on the PKC, MAPK, and IKK-mediated signaling pathways. First, we assessed PKC phosphorylation to determine whether the inhibition of BTK expression influences PKC activation in MCF-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 reduced TPA-induced translocation of PKCβ to the membrane. We also assessed the phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and JNK after treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 to determine the effects of BTK inhibitors on TPA-induced MAPK activation. Ibrutinib and CNX-774 treatment reduced p-p38, p-ERK, and p-JNK expression (Fig. 3B). In addition, we examined the effects of ibrutinib and CNX-774 on the activation of the IKK protein, a signal transducer downstream of the TPA-induced PKC signaling pathway, but upstream of the NF-κB signal transduction cascade. We also confirmed that ibrutinib and CNX-774 treatment inhibited TPA-induced phosphorylation of IKKαβ and that TPA induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα However, IκBα phosphorylation was suppressed in cells treated with the BTK inhibitors, thereby preventing its degradation (Fig. 3C). The results indicate that the inhibition of BTK expression regulates PKCβ activation and MAPK/IKK signal transduction, and, in turn, regulates TPA-induced MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells.

Figure 3.

BTK inhibitors decrease TPA-induced activation of the PKC, MAPK, and IKK signaling pathways in MCF-7 cells. The cells were pretreated with BTK inhibitors for 1 h and then stimulated with TPA. The cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting of the PKCα, PKC δ, and PKCβ levels in the cytosolic and membrane fractions. The blot was reprobed with an antibody against Na k-ATPase to confirm equal loading (A). Cells (1×106) were pretreated with BTK inhibitors and then stimulated with TPA for 15 min. Cell lysates were assessed by western blotting using antibodies against p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and their phosphorylated forms (B), and the levels of p-IκBα, IκBα, p-IKKαβ, IKKα, and IKKβ were determined (C). The blot was reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P<0.01 vs. untreated control; *P<0.01 vs. TPA. The blot was reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading.

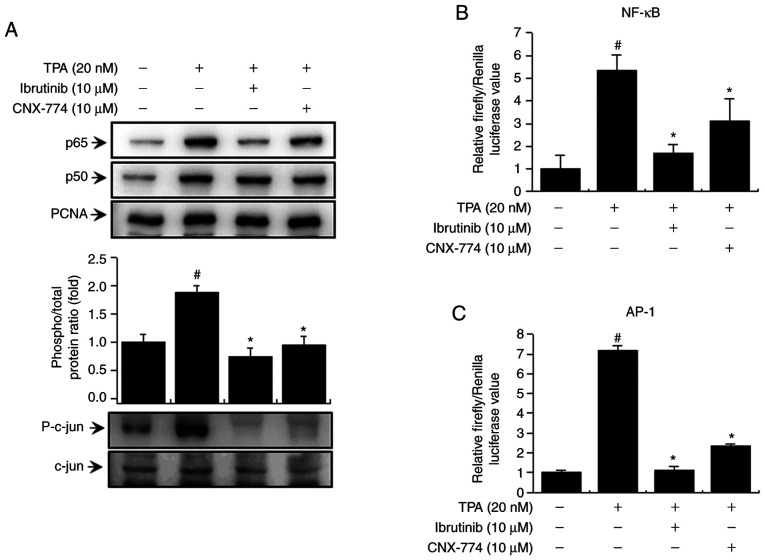

Inhibition of BTK expression reduces TPA-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in MCF-7 cells

We examined the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 to verify the signaling mechanism downstream of PKC/MAPK and IKK. We confirmed that the BTK inhibitors reduced the levels of p65 and p50, the subunits of NF-κB, and p-c-Jun (Fig. 4A). In addition, to validate NF-κB and AP-1 activation, we examined the effects of ibrutinib and CNX-774 on promoter binding using the luciferase reporter assay. We observed an increase in TPA-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in MCF-7 cells and suppression of TPA-induced NF-κB and AP-1 activation after treatment with the BTK inhibitors (Fig. 4B and C). These findings suggest that the inhibition of BTK expression regulates TPA-induced MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells by suppressing the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 via various signaling mechanisms.

Figure 4.

BTK inhibitors block TPA-induced NF-κB and AP-1 activation in MCF-7 cells. Cells (2×106) were pretreated with BTK inhibitors and then stimulated with TPA for 3 h. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the nuclear levels of NF-κB (p65 and p50) and AP-1 (p-c-Jun). The blot was reprobed with an antibody against proliferating cell nuclear antigen to confirm equal loading (A). NF-κB-Luc or AP-1-Luc reporter and Renilla luciferase thymidine kinase reporter vector were co-transfected into MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated with BTK inhibitors and stimulated with TPA and the promoter activity of NF-κB and AP-1 was measured with dual luciferase reporter assays (B and C). Data are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. #P<0.01 vs. untreated control; *P<0.01 vs. TPA.

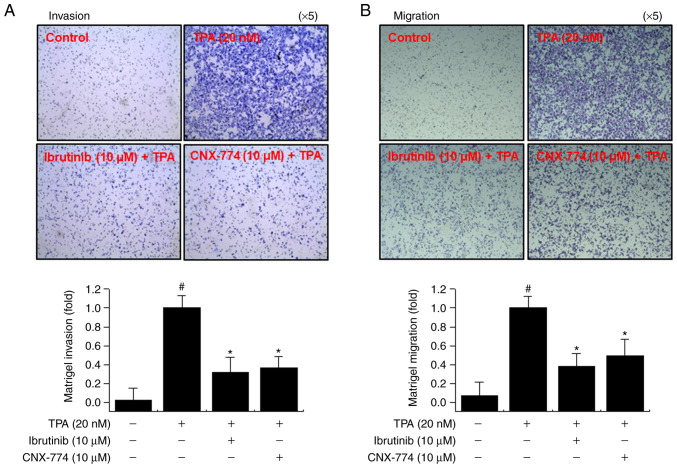

Inhibition of BTK expression suppresses TPA-mediated invasion and migration of MCF-7 cells

The upregulation of MMP-9 expression contributes to the metastasis of cancer cells, including breast cancer (21,41). We performed Matrigel invasion and cell migration assays to determine whether the inhibition of BTK expression suppresses MCF-7 cell invasion and migration in vitro. We observed a marked decrease in the invasion and migration of MCF-7 cells following treatment with ibrutinib and CNX-774 (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the inhibition of BTK expression suppresses cancer cell metastasis.

Figure 5.

BTK inhibitors suppress TPA-induced Matrigel invasion and migration of MCF-7 cells. The invasive ability of cells following treatment with BTK inhibitors and TPA was determined using a Matrigel invasion assay (magnification, ×5). BTK inhibitors block 12-O-TPA-induced Matrigel invasion of MCF-7 cells. Cells (3×105) were seeded onto the upper chamber of Matrigel-coated wells and BTK inhibitors and TPA were placed in the bottom wells. After 24 h, the cells attached to the bottom of the filter were fixed, stained, and counted. The error bars are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate, #P<0.005 vs. untreated control; *P<0.005 vs. control + TPA.

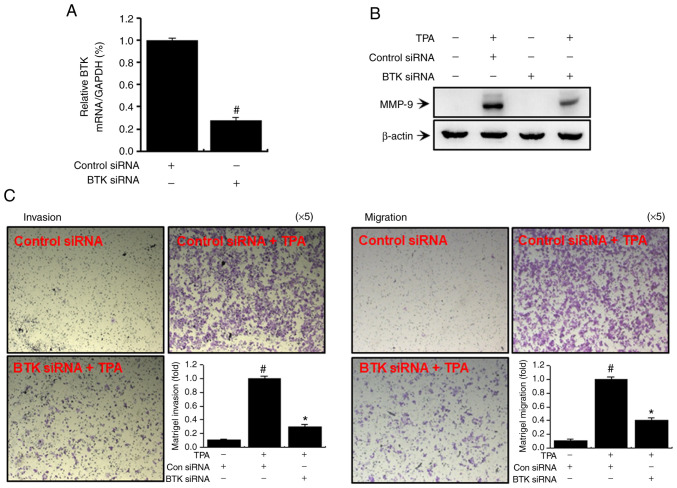

Downregulation of BTK expression suppresses TPA-induced MMP-9 expression along with MCF-7 breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis

We regulated BTK expression in MCF-7 cells by gene silencing using siRNA to further substantiate our findings based on inhibitor-induced suppression of BTK expression. As shown in Fig. 6A, we transfected MCF-7 cells with BTK and control siRNAs and performed quantitative PCR after 24 h to validate the knockdown of BTK. A significant decrease in TPA-induced MMP-9 expression was observed when BTK was silenced (Fig. 6B). Transfection with BTK siRNA significantly reduced TPA-induced cellular invasion and metastasis (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

BTK siRNA inhibits TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and Matrigel invasion and migration of MCF-7 cells. BTK expression was significantly suppressed in MCF-7 cells transfected with BTK siRNA. BTK levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR with GAPDH as an internal control (A). Transfected cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using an anti-MMP-9 antibody (B). Transfected cell lysates were subjected to Matrigel invasion and migration analyses (magnification, ×5) (C). The error bars are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. #P<0.005 vs. control; *P<0.005 vs. control + TPA.

Discussion

Breast cancer-related mortality commonly results from the metastasis of breast cancer cells to the bones, lung, liver, brain, and kidney (4). Metastasis is considered a defining characteristic of breast cancer and primary cause of patient mortality. The initial phase of invasion and metastasis of cancer cells involves the degradation of ECM, which functions as a biochemical and mechanical barrier (7,42). ECM degradation requires the expression and activation of MMPs, which play a major role in breast cancer progression (41,42). Among the MMPs, MMP-9 is a crucial protein involved in tumor progression and, metastasis, including breast cancer (26,43). MMP-9 expression activates various intracellular signaling pathways in breast cancer cells via inflammatory cytokines, hormones, growth factors, and TPA (41,43).

In this study, we aimed to establish the role of BTK in TPA-induced MMP-9 expression as well as in the invasion and migration of MCF-7 cells. A previous study has reported that BTK translocates to the plasma membrane and, is phosphorylated by Src family kinases, and, in turn, phosphorylates and activates PLCγ2 (13). Activated PLCγ2 catalyzes PIP2 hydrolysis to generate IP3 and DAG. DAG then promotes Ca2+ discharge from IP3 intracellular storage. DAG and Ca2+, in turn, activate PKCb, which then induces activation of the Ras/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling cascade that promotes cell growth and proliferation (36,44–46). Previous studies have focused more on the role of BTK in B-cell leukemia and lymphomas (47,48), which provides the basis for kinase-targeted approaches to treat malignant tumors. However, the role of BTK in metastatic cancer, including breast cancer, remains unclear. Therefore, we examined whether suppressing BTK2 expression regulates PLCγ2/PKC-mediated MMP-9 expression and invasion or migration in MCF-7 cells. Our results confirmed that the inhibition of BTK expression suppresses TPA-induced MMP-9 expression, invasion, and migration and that PLCγ2 is involved in the regulation of TPA-induced MMP-9 expression.

Another major objective of this study was to investigate the anti-invasive activity of the downregulation of BTK expression in the regulation of PKC-activated MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells express various types of PKCs that play an important role in cell metastasis (18,49). Therefore, this study was mainly performed on MCF-7 cells. In addition, it was confirmed that the inhibition of BTK expression inhibited MMP-2 and −9 expression and invasion or migration in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. S1). However, our results may be limited to the inhibitory effects of metastasis in ER+ MCF-7 breast cancer cells. The ability of TPA to activate PKC is possible due to the similarity of TPA to DAG, a natural activator of classical PKC isoforms. Activated PKC enhances the invasion of breast cancer cells by promoting MMP-9 expression (50). TPA binds to the C1 domain of PKC isoforms to activate them (51,52). TPA-mediated PKC activation induces PKC isozymes to translocate to the cell membranes, thereby leading to differential gene expression, proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and malignant regulation in cancer cells (51,53). The activation of PKC isozymes is achieved by the binding of DAG and Ca2+ (18). Various signaling molecules are situated downstream of the PKC isozymes, including Ras/Raf/MAPKs, phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt, and transcription factors (NF-κB, AP-1, and STAT-3) (18,32). In previous studies, we have shown that TPA-mediated activation of PKCα, PKCb, and PKCδ mediates the expression and secretion of MMP-9 (31,54). The present study demonstrated that the inhibition of BTK expression reduced TPA-mediated activation of PKC isozymes in MCF-7 cells.

We evaluated the DNA binding of transcription factors (NF-κB and AP-1) downstream of MAPKs and IKK and determined the TPA-induced PKC-mediated downstream signaling cascade with respect to MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells. MAPKs (ERK, p38, and JNK), as upstream regulators of NF-κB, have been reported to induce MMP-9 expression and activation (55). The activation of MAPK in MCF-7 cells has been confirmed through phosphorylation (56). NF-κB and AP-1 are activated by the IKK, MAPKs, or PI3K/Akt depending on the cell type (37,57–60). Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 is important in MMP-9 regulation because the NF-κB and AP-1 binding sites in the MMP-9 promoter are involved in this activation (29,58). We confirmed that the inhibition of BTK expression suppressed NF-κB and AP-1 activation, while it suppressed MAPK and IKK activation at the upstream level.

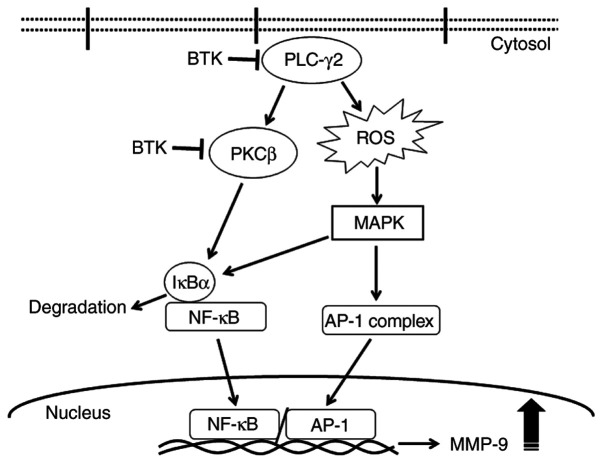

In conclusion, the inhibition of BTK expression reduced TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and metastasis by blocking NF-κB and AP-1 activation via the PLCγ/PKC/MAPK and IKK signaling pathways (Fig. 7). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to validate that BTK mediates the metastasis of MCF-7 cells by regulating the PLCγ2/PKC signaling pathways, consequently suppressing MMP-9 expression. Therefore, we suggest that regulating BTK expression may serve as a therapeutic strategy to inhibit metastasis of MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

Figure 7.

Schematic signaling pathway of the effect of downregulation of BTK expression on TPA-induced MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 cells. Inhibition of BTK expression attenuates TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and metastasis by blocking NF-κB and AP-1 activation via the PLCγ2/PKC/MAPK and IKK signaling pathways. →, activated; ⊥ means inhibited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2015R1D1A1A01057605, 2017R1A5A2015061), Republic of Korea. The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2015R1D1A1A01057605, 2017R1A5A2015061), Republic of Korea. The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

YRL, JP, and HJY designed the study. JMK, EMN, and HKS performed the experiments. SYK and SHJ analyzed the western blot and RT-PCR data. JSK and BHP provided additional experimental comments and analyzed the data. YRL drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang SY, Kim YS, Kim Z, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Park S, Bae SY, Yoon KH, Lee SB, Lee SK, et al. Breast cancer statistics in Korea in 2017: Data from a breast cancer registry. J Breast Cancer. 2020;23:115–128. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2020.23.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redig AJ, McAllister SS. Breast cancer as a systemic disease: A view of metastasis. J Intern Med. 2013;274:113–126. doi: 10.1111/joim.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leber MF, Efferth T. Molecular principles of cancer invasion and metastasis (review) Int J Oncol. 2009;34:881–895. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang WG, Sanders AJ, Katoh M, Ungefroren H, Gieseler F, Prince M, Thompson SK, Zollo M, Spano D, Dhawan P, et al. Tissue invasion and metastasis: Molecular, biological and clinical perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35(Suppl 1):S244–S275. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Zijl F, Krupitza G, Mikulits W. Initial steps of metastasis: Cell invasion and endothelial transmigration. Mutat Res. 2011;728:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Treon SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, Warren D, Varma G, Green R, Argyropoulos KV, Yang G, Cao Y, Xu L, et al. Ibrutinib in previously treated Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1430–1440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, Yang G, Hunter ZR, Liu X, Xu L, Chen J, Tsakmaklis N, Hatjiharissi E, Kanan S, Davids MS, et al. The BCL2 antagonist ABT-199 triggers apoptosis, and augments ibrutinib and idelalisib mediated cytotoxicity in CXCR4 Wild-type and CXCR4 WHIM mutated Waldenstrom macroglobulinaemia cells. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:134–138. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal Singh S, Dammeijer F, Hendriks RW. Role of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cells and malignancies. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:57. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0779-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HO. Development of BTK inhibitors for the treatment of B-cell malignancies. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s12272-019-01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohamed AJ, Yu L, Bäckesjö CM, Vargas L, Faryal R, Aints A, Christensson B, Berglöf A, Vihinen M, Nore BF, Smith CI. Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk): Function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:58–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampson BL, Brown JR. Are BTK and PLCG2 mutations necessary and sufficient for ibrutinib resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia? Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:185–194. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2018.1435268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halcomb KE, Contreras CM, Hinman RM, Coursey TG, Wright HL, Satterthwaite AB. Btk and phospholipase C gamma 2 can function independently during B cell development. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilde JI, Watson SP. Regulation of phospholipase C gamma isoforms in haematopoietic cells: Why one, not the other? Cell Signal. 2001;13:691–701. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koivunen J, Aaltonen V, Peltonen J. Protein kinase C (PKC) family in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isakov N. Protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms in cancer, tumor promotion and tumor suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;48:36–52. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabinski N, Ewald F. Ibrutinib (ImbruvicaTM) potently inhibits ErbB receptor phosphorylation and cell viability of ErbB2-positive breast cancer cells. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:1096–1104. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Kinoshita T, Sukbuntherng J, Chang BY, Elias L. Ibrutinib Inhibits ERBB receptor tyrosine kinases and HER2-amplified breast cancer cell growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2835–2844. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stetler-Stevenson WG, Hewitt R, Corcoran M. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor invasion: From correlation and causality to the clinic. Semin Cancer Biol. 1996;7:147–154. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer. Essays Biochem. 2002;38:21–36. doi: 10.1042/bse0380021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brinckerhoff CE, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinases: A tail of a frog that became a prince. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nrm763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weng CJ, Chau CF, Hsieh YS, Yang SF, Yen GC. Lucidenic acid inhibits PMA-induced invasion of human hepatoma cells through inactivating MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathway and reducing binding activities of NF-kappaB and AP-1. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:147–156. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandooren J, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9): The next decade. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;48:222–272. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.770819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scorilas A, Karameris A, Arnogiannaki N, Ardavanis A, Bassilopoulos P, Trangas T, Talieri M. Overexpression of matrix-metalloproteinase-9 in human breast cancer: A potential favourable indicator in node-negative patients. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1488–1496. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roomi MW, Kalinovsky T, Rath M, Niedzwiecki A. Modulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion by cytokines, inducers and inhibitors in human glioblastoma T-98G cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:1907–1913. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton AC. Regulation of protein kinase C. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:161–167. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(97)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin CW, Hou WC, Shen SC, Juan SH, Ko CH, Wang LM, Chen YC. Quercetin inhibition of tumor invasion via suppressing PKC delta/ERK/AP-1-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation in breast carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1807–1815. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SO, Jeong YJ, Kim M, Kim CH, Lee IS. Suppression of PMA-induced tumor cell invasion by capillarisin via the inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent MMP-9 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noh EM, Park YJ, Kim JM, Kim MS, Kim HR, Song HK, Hong OY, So HS, Yang SH, Kim JS, et al. Fisetin regulates TPA-induced breast cell invasion by suppressing matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation via the PKC/ROS/MAPK pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;764:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JM, Noh EM, Kwon KB, Kim JS, You YO, Hwang JK, Hwang BM, Kim BS, Lee SH, Lee SJ, et al. Curcumin suppresses the TPA-induced invasion through inhibition of PKCα-dependent MMP-expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2012;19:1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HR, Kim JM, Kim MS, Hwang JK, Park YJ, Yang SH, Kim HJ, Ryu DG, Lee DS, Oh H, et al. Saussurea lappa extract suppresses TPA-induced cell invasion via inhibition of NF-κB-dependent MMP-9 expression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:170. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park SY, Kim YH, Kim Y, Lee SJ. Frondoside A has an anti-invasive effect by inhibiting TPA-induced MMP-9 activation via NF-κB and AP-1 signaling in human breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:933–940. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SH, Kim JH, Lee DH, Kang JW, Song HH, Oh SR, Yoon DY. Luteolin 8-C-β-fucopyranoside inhibits invasion and suppresses TPA-induced MMP-9 and IL-8 via ERK/AP-1 and ERK/NF-κB signaling in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochimie. 2013;95:2082–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roskoski R., Jr ERK1/2 MAP kinases: Structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:105–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo YJ, Pan WW, Liu SB, Shen ZF, Xu Y, Hu LL. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19:1997–2007. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SO, Jeong YJ, Im HG, Kim CH, Chang YC, Lee IS. Silibinin suppresses PMA-induced MMP-9 expression by blocking the AP-1 activation via MAPK signaling pathways in MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JM, Noh EM, Song HK, You YO, Jung SH, Kim JS, Kwon KB, Lee YR, Youn HJ. Silencing of casein kinase 2 inhibits PKC-induced cell invasion by targeting MMP-9 in MCF-7 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:8397–8402. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duffy MJ, Maguire TM, Hill A, McDermott E, O'Higgins N. Metalloproteinases: Role in breast carcinogenesis, invasion and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:252–257. doi: 10.1186/bcr65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991;5:2145–2154. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.8.1850705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yousef EM, Tahir MR, St-Pierre Y, Gaboury LA. MMP-9 expression varies according to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:609. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roskoski R., Jr RAF protein-serine/threonine kinases: Structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roskoski R., Jr MEK1/2 dual-specificity protein kinases: Structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roskoski R., Jr A historical overview of protein kinases and their targeted small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hendriks RW, Yuvaraj S, Kil LP. Targeting Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:219–232. doi: 10.1038/nrc3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buggy JJ, Elias L. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) and its role in B-cell malignancy. Int Rev Immunol. 2012;31:119–132. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.664797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawakami T, Kawakami Y, Kitaura J. Protein kinase C beta (PKC beta): Normal functions and diseases. J Biochem. 2002;132:677–682. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Anastasiadis PZ, Liu Y, Thompson EA, Fields AP. Protein kinase C (PKC) betaII induces cell invasion through a Ras/Mek-, PKC iota/Rac 1-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22118–22123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry OP, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C isozymes, novel phorbol ester receptors and cancer chemotherapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1725–1744. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazanietz MG. Novel ‘nonkinase’ phorbol ester receptors: The C1 domain connection. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:759–767. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urtreger AJ, Kazanietz MG, Bal de Kier Joffé ED. Contribution of individual PKC isoforms to breast cancer progression. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:18–26. doi: 10.1002/iub.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, Chakraborti T. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: An overview. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:269–285. doi: 10.1023/A:1026028303196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi M, Elion EA. MAP kinase pathways. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3569–3572. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao J, Xiong S, Klos K, Nguyen N, Grijalva R, Li P, Yu D. Multiple signaling pathways involved in activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) by heregulin-beta1 in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:8066–8074. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitmarsh AJ. Regulation of gene transcription by mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1285–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3279–3290. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang N, Dai Q, Su X, Fu J, Feng X, Peng J. Role of PI3K/AKT pathway in cancer: The framework of malignant behavior. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:4587–4629. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05435-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.