Abstract

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic, reports of xenophobic and racist incidents directed at Chinese Americans have escalated. The present study adds further understanding to potential psychosocial effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic by comparing self‐reported questionnaire data from two groups of Chinese students attending a public university in western United States: the group who participated in the study before the outbreak of COVID‐19 (Pre‐COVID, N = 134), and the group who participated at the beginning (during‐COVID, N = 64). The aim of the study was to: (a) compare mean differences in perceived discrimination and anxiety between the two groups, (b) test whether COVID‐19 moderated the link between perceived discrimination and anxiety, and (c) examine whether media exposure portraying Chinese individuals negatively mediated relations between COVID‐19 and discrimination. Results showed that the During‐COVID group reported higher perceived discrimination and anxiety than the Pre‐COVID group. The link between perceived discrimination and anxiety was stronger for the During‐COVID group. Mediation analyses suggested that negative Chinese media exposure partly accounted for the group difference in perceived discrimination. Results suggest that future studies on the psychosocial implications of the COVID‐19 pandemic should consider the role of discrimination in understanding the mental health of Chinese American college students.

Keywords: Discrimination, Covid‐19 pandemic, Anxiety, Media exposure, Minority stress

Racial discrimination is a salient societal issue and has been recognised as a risk factor for mental health problems in racial and ethnic minorities (Schmitt et al., 2014). In order to intervene in these associations, researchers have sought a better understanding of the complex factors involved in the links between discrimination and mental health. To date, research has largely focused on characterising individual‐level factors involved in psychological responses to discrimination, while there is little research on the impact of major global events on individuals' experiences of discrimination. Following the outbreak of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID‐19), objective reports of discrimination towards Chinese people and anti‐Asian hate crimes have increased (Devakumar et al., 2020; Gover et al., 2020). Perceptions of being treated unfairly because of one's race or ethnicity (perceived discrimination) may heighten already elevated anxiety. The link between perceived discrimination and anxiety might be stronger in the context of COVID‐19, which limited individuals' access to protective factors such as social support. Furthermore, increases in perceived discrimination could be perpetuated by global media content that ties disease threat to the Chinese community (negative Chinese media exposure). Taken together, the context of COVID‐19 has several psychosocial implications for Chinese‐origin individuals.

The present study examined links among perceived discrimination, negative Chinese media exposure and anxiety symptoms in Chinese American (CA) college students in the context of COVID‐19 pandemic. We compared participants' self‐reported perceived discrimination, media exposure and anxiety symptoms between the group who completed the measures prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic (Pre‐COVID) and the group who completed the measures during the pandemic (During‐COVID). We also tested whether the COVID‐19 context moderated the relation between perceived discrimination and anxiety. Finally, we explored whether negative Chinese media exposure mediated the link between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination.

THE COVID‐19 PANDEMIC: LINKS TO PERCEIVED DISCRIMINATION AND ANXIETY

Although racial discrimination occurs outside of the context of disease outbreaks, the fear elicited by infectious diseases is theorised to augment instances of discrimination (Pappas et al., 2009). For example, the 2003 SARS epidemic (which originated in China) led to discrimination directed at Chinese American communities (Eichelberger, 2007). Similarly, the 2014 Ebola outbreak (which originated in Africa) resulted in instances of discrimination towards U.S. individuals of African descent (Monson, 2017). After the outbreak of COVID‐19 in China, news outlets reported numerous incidences of discrimination towards Chinese Americans (Tavernise & Oppel, 2020). Despite the positive image portrayed by the “model minority” stereotype, perceived discrimination is a prevalent experience outside of the COVID‐19 pandemic and has been identified as a risk factor for mental health problems in Chinese American youth (Benner & Kim, 2009; Juang et al., 2018). However, whether Chinese Americans have perceived more discrimination compared to before COVID‐19 has yet to be empirically investigated. Examining associations between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination in Chinese American college students is especially salient given that college campuses host a mixing of students from multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds.

COVID‐19 has also coincided with increased reports of anxiety, mirroring prior infectious disease outbreaks (American Psychiatric Association, 2020). This anxiety may stem from fear of infection, disruption of routines, supply shortages, or worry over finances or employment. Preliminary studies suggest that young adults may experience greater anxiety symptoms during COVID‐19 compared to other age groups, potentially because of increased consumption of COVID‐19 information (Qiu et al., 2020). Understanding whether Chinese American college students report increased anxiety symptoms after COVID‐19 has implications for college counselling centres.

CONTEXT AS A MODERATOR OF THE LINKS BETWEEN PERCEIVED DISCRIMINATION AND ANXIETY

According to Bronfenbrenner's ecological theory, developmental outcomes are shaped by interactions between individuals and their surrounding contexts (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). Building on Bronfenbrenner's theory, the integrative risk and resilience (IRR) model emphasises the salience of contextual factors for immigrant‐origin and ethnic minority youth (Suárez‐Orozco et al., 2018). According to the IRR model, psychological adjustment occurs within four nested levels of context: individual, microsystems, political‐social and global. Extant research primarily focuses on moderation of perceived discrimination's effects at the individual and microsystems levels (Schmitt et al., 2014), and has highlighted the importance of considering context. For example, relations between perceived discrimination and psychological distress in Chinese American adults were stronger in neighbourhoods with a higher density of Chinese American residents (Syed & Juan, 2012), potentially because experiencing discrimination in a supposedly safe context was more stressful and jarring. In a sample of Black American adolescents, links between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms were observed for youth attending majority Black or White schools, but not for youth attending racially diverse schools (Seaton & Douglass, 2014). Taken together, these studies suggest that context can moderate associations between perceived discrimination and psychological adjustment. No studies have examined whether global crises such as the COVID‐19 pandemic as a macro context might moderate the associations between perceived discrimination and anxiety.

Specifically, the context of COVID‐19 may decrease the efficacy or availability of factors that protect against the negative psychological effects of perceived discrimination (e.g., social support, access to or engagement in pleasurable activities), or may render perceived discrimination towards Chinese individuals more potent. Investigating whether COVID‐19 moderates the links between perceived discrimination and anxiety symptoms in Chinese American college students can inform mental health support and intervention efforts serving these students. In addition, such an investigation can contribute to the broader understanding of how contextual factors influence psychological reactions to discrimination.

NEGATIVE MEDIA PORTRAYAL AND PERCEIVED DISCRIMINATION DURING COVID‐19

One potential pathway by which the onset of COVID‐19 may relate to increased perceived discrimination is through news and social media. According to framing and cultivation theories, the news media selects for audiences the topics that are an important focus and “frames” whether those topics should be perceived negatively or positively. This frame can then “cultivate” viewers perceptions of reality over time to match what is portrayed in the media (Morgan & Shanahan, 2010). Consistent with framing and cultivation theories, research has shown that exposing participants to negative media frames of Black individuals resulted in higher endorsement of negative Black stereotypes (Ramasubramanian, 2011). Framing and cultivation theories have also been used to explain discrimination towards certain racial/ethnic groups after major global events such as towards Muslim Americans after the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Powell, 2011) and towards Chinese American communities after the 2003 SARS epidemic (Eichelberger, 2007). These studies suggest that global events may lead to negative media portrayal of certain racial/ethnic groups, resulting in increased discrimination towards those groups. Several researchers and journalists have speculated that negative media portrayals of Chinese‐origin individuals may be partially responsible for spikes in discriminatory acts towards Chinese individuals after COVID‐19 (Asian American Journalists Association, 2020; Timberg & Chiu, 2020). The present study explores this speculation to shed light on one potential mechanism by which COVID‐19 may shape perceptions of discrimination.

THE PRESENT STUDY

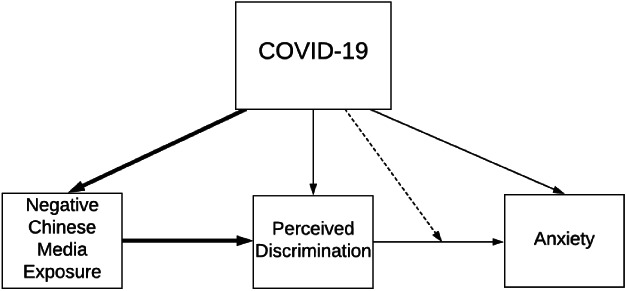

The overall goal of the present study is to better understand the psychosocial correlates of COVID‐19 in a sample of Chinese American (CA) college students. The aims of the study are visually depicted in Figure 1. The first aim of the study was to test whether the onset of COVID‐19 is associated with increased perceived discrimination and anxiety in CA college students. Using a cross‐sectional, between‐subjects design, we compared self‐reported discrimination and anxiety symptoms between Pre‐COVID and During‐COVID groups. Given preliminary research showing increased discrimination and anxiety after COVID‐19 onset (American Psychiatric Association, 2020; Devakumar et al., 2020), we hypothesised that the During‐COVID group would show greater perceived discrimination and anxiety symptoms compared to the Pre‐COVID group. The second aim of the study was to test the relation between perceived discrimination and anxiety, and whether the COVID‐19 context moderated the relation. We hypothesised that links between perceived discrimination and anxiety would be stronger in the During‐COVID group than the Pre‐COVID group because of reduced availability of protective factors. The third aim was to examine whether the onset of COVID‐19 is associated with increased negative Chinese media exposure, which in turn might mediate the link between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination. Informed by the framing and cultivation theories and the role of media in propagating discrimination during prior global events, we expected that negative Chinese media exposure would mediate relations between COVID‐19 (Pre‐ vs. During‐COVID‐19) and perceived discrimination.

Figure 1.

Hypothesised relations among study constructs, whereby COVID‐19 is expected to have direct effects on perceived discrimination and anxiety (Aim 1). The dashed arrow represents the hypothesised moderating role of COVID‐19 (Aim 2), while the bolded arrows indicated the hypothesised mediating role of negative Chinese media exposure (Aim 3).

METHODS

Procedure

The present study was part of a larger, cross‐sectional study on reactions to perceived discrimination in a sample of Chinese American college students recruited from a large public university in western United States. To be included in the study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age, identify as Chinese American, and be enrolled at the university where the study took place. Participants were recruited through flyers and email advertisements sent to Chinese student organisations and psychology courses. Interested individuals completed an online screening questionnaire that assessed for aforementioned eligibility criteria. Eligible participants then completed a 30‐minute online questionnaire that assessed demographic variables (age, gender, generation status, years in the United States and parental education) and the measures described below. All instruments were administered in English. Participants could choose to receive either a $5 gift card or course credit for completing the survey. All participants provided informed electronic consent for the study, and all study procedures were approved by an institutional review board. The online screening questionnaire, electronic consent and online study questionnaire were completed by participants remotely. A subset of participants also completed in‐person procedures involving collection of psychophysiological data—these data are not the subject of the present study and are reported elsewhere. All study procedures were pre‐registered using the Open Science Framework repository prior to any researcher accessing the data (https://osf.io/cw4sa). Given that COVID‐19 was unanticipated at the time of study pre‐registration (October 2019), the hypotheses investigated in the present study were not pre‐registered.

Participants completed questionnaires in two phases: during the fall semester (September 9, 2019–December 4, 2019) and the spring semester (February 4, 2020–March 23, 2020) of the academic school year. The first case of COVID‐19 was reported on December 31, 2019, and the first case was confirmed in the United States on January 20, 2020. Thus, students who completed the survey during the spring semester (N = 64) participated During‐COVID, while students who completed the survey during the fall semester (N = 134) participated Pre‐COVID. Given the self‐identification requirement of “Chinese American” for participants and to preserve brevity in our terminology, we hereafter refer to all participants as “Chinese American” students even though our sample includes some Chinese international students (N = 41).

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UC Berkeley Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Measures

Perceived discrimination

Participants completed the Everyday Discrimination Scale which uses nine items (Williams et al., 1997) to measure perceived discrimination. Items assess the frequency with which participants feel they are treated in a certain way because of their race or ethnicity (e.g., “You are called names or insulted”) using a 4‐point Likert‐type response format. An additional item was added to modify the original scale for use with a Chinese sample (“People assume my English is poor”). This modified version of the scale has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in prior studies with Chinese samples (Benner & Kim, 2009). Mean scores are calculated to yield a composite ranging from 1 to 4 (as in Benner & Kim, 2009), with higher scores indicating greater perceived discrimination. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha showed good reliability for the scale (α= 0.87).

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). On the BAI, participants rate the frequency with which they have experienced each of 21 anxiety symptoms over the past month (0 = not at all, 1 = mildly, 2 = moderately and 3 = severely). Symptoms describe somatic, cognitive and emotional manifestations of anxiety (e.g., feeling hot, fear of worst happening, scared). Items are summed to yield a total score between 0 and 63, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety. Cronbach's alpha indicated that the BAI had excellent reliability with the present sample (α=0.95).

Overall media exposure

Overall media exposure was assessed with questions about the time spent on internet, social media, podcasts, newspapers, television, radio and magazines. Questions were based off of other self‐report measures to assess media use (Althaus & Tewksbury, 2007). Participants indicated the average daily time spent on each form of media, which was coded into hours as follows: “never” = 0, “less than 30 minutes”=0.25 hour, “30 minutes to 1 hour”=0.75 hour, “1 to 2 hours”=1.5 hours, “2 to 3 hours”=2.5 hours, “more than 3 hours”=3 hours. Items were summed to yield a single score that represented the total time spend on media on an average day (α=0.58).

Negative Chinese media exposure

Negative Chinese media exposure was assessed with one question. Participants were asked: “Think about the content that you see on various forms of media. How often have you seen Chinese immigrants portrayed negatively in the media?.” Participants responded using the following options: 0 = never, 1 = less than once a week, 2 = once a week, 3 = several times a week, 4 = once a day, 5 = several times a day. The coded numeric response was used in analysis, with higher scores indicating greater self‐reported negative Chinese media exposure.

Covariates

We considered and controlled for several variables that might confound associations between negative Chinese media exposure, perceived discrimination and anxiety. Demographic characteristics such as age, gender and socioeconomic status have been shown in separate studies to relate to all key study variables (Juang et al., 2018; Williams et al., 1997). In addition, differences in immigration history as measured by years in the United States and generational status relate to both perceived discrimination and anxiety (Juang et al., 2018). Thus, the following variables obtained from self‐report are investigated as covariates in the present study: age, gender, parental education, years in United States, generational status and overall media exposure.

Analytic plan

First, descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, maximums, minimums, skewness and kurtosis values) were computed. Cutoff values of 2 and 7 for skewness and kurtosis, respectively were used to determine if variables were normally distributed. Second, correlation analyses were used to examine relations among hypothesised covariates and main study variables. Third, the Pre‐ and During‐COVID groups were compared on all study variables using independent samples t‐tests for continuous variables and chi‐square tests for categorical variables. Fourth, a linear regression model with anxiety as the outcome and COVID‐19, perceived discrimination and their interaction as predictors was tested. The perceived discrimination predictor was mean‐centred prior to computing the interaction term. A Cook's distance cutoff value of 1 was used for outlier identification. Multicollinearity was examined using variance inflation factors with a cutoff value of 7. Listwise deletion was used to handle one missing data value given that the value appeared to be missing at random. Finally, to test hypothesised direct and indirect relations between study variables, path analysis was conducted. In the model, COVID‐19 was hypothesised to simultaneously predict negative Chinese media exposure and perceived discrimination. Negative Chinese media exposure was hypothesised to predict perceived discrimination. The model was estimated in Mplus 8.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2019) using full‐information maximum likelihood to handle missing data and a maximum likelihood method of estimation. To assess model fit, we used the following cutoff criteria: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ .95, root‐mean‐square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .06, and standardised root‐mean‐square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for all continuous study variables are displayed in Table 1. All variables were normally distributed. Overall, there was a small proportion of missing data—all variables had complete data except for a few missing values of parental education (1%), overall media exposure (1%), negative Chinese media exposure (1%) and anxiety (<1%).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables for the full sample and by context (pre‐ vs. during‐COVID‐19)

| Full sample (N = 198) | Pre‐COVID (N = 134) | During‐COVID (N = 64) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 18 | 25 | 20.01 | 1.32 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 19.92 | 1.29 | 20.19 | 1.37 |

| Years in the United Statess† | 0 | 24 | 14.39 | 7.68 | −0.77 | −1.13 | 13.74 | 7.77 | 15.75 | 7.38 |

| Parental education (years) | 0 | 21 | 15.29 | 3.75 | −1.13 | 1.81 | 15.43 | 3.75 | 15.01 | 3.74 |

| Overall media exposure (hours/day)† | 0 | 14.50 | 6.67 | 2.52 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 6.44 | 2.33 | 7.13 | 2.84 |

| Negative Chinese media exposure* | 0 | 6 | 2.53 | 1.56 | 0.49 | −0.65 | 2.35 | 1.49 | 2.92 | 1.64 |

| Perceived discrimination*** | 1 | 4 | 1.77 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.33 | 1.68 | 0.49 | 1.96 | 0.48 |

| Anxiety*** | 0 | 57 | 12.07 | 11.17 | 1.22 | 1.41 | 10.26 | 10.46 | 15.90 | 11.74 |

Notes. Variables with star(s) indicate significant mean differences between the two groups based on independent samples t‐tests with equal variance assumed: † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .005.

The final sample for the current study consisted of 198 Chinese American college students between 18 and 25 years of age (M = 20.0 years, SD = 1.32), described in Table 1. The sample identified as 55.6% (N = 110) female and 44.4% (N = 88) male. Participants had resided in the United States for 14.4 years on average (SD = 7.73), with 29.8% (N = 59) reporting being born in China (first‐generation), 43.4% (N = 86) reporting that their parents were born in China (second‐generation) and 26.8% (N = 53) reporting that their grandparents were born in China (third‐generation). Participants indicated their parents' educational attainment, which ranged from 0 years (no formal schooling) to 21 years (doctorate or medical degree; M = 14.43 years, SD = 7.73). All participants were enrolled in a large (>30,000 enrolled undergraduates) public university with a relatively racially diverse student body (approximately 75% non‐white students with roughly 17% Chinese‐origin students overall).

Correlation analyses

In terms of hypothesised covariates, correlation analyses (Table 2) showed that an increase in generation status from being born in China (1st generation) to having grandparents born in China (3rd generation) was marginally correlated with greater negative Chinese media exposure (r = .13, p = .077) and significantly correlated with greater perceived discrimination (r = .14, p = .044). In a parallel manner, greater years in the United States was correlated with greater negative Chinese media exposure (r = .18, p = .012) and greater perceived discrimination (r = .17, p = .018). Overall, media exposure was positively correlated with negative Chinese media exposure (r = .29, p < .001), perceived discrimination (r = .30, p < .001) and anxiety (r = .29, p < .001). Thus, in subsequent regression and path analyses, for regressions or paths with perceived discrimination as the dependent variable, generation status, years in the United States and overall media exposure are included as covariates. For regressions or paths with anxiety as the dependent variable, overall media exposure is included as a covariate.

TABLE 2.

Pairwise correlations between study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COVID (0 = Pre, 1 = During) | — | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 0.10 | — | |||||||

| 3. Gender (0 = Male, 1 = Female) | −0.25*** | 0.01 | — | ||||||

| 4. Generation (1 = 1st, 2 = 2nd, 3 = 3rd) | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.17* | — | |||||

| 5. Years in US | 0.12† | 0.07 | −0.14† | 0.52*** | — | ||||

| 6. Parental Education | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.12† | — | |||

| 7. Overall Media Exposure | 0.13† | 0.22** | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | — | ||

| 8. Negative Chinese Media Exposure | 0.17* | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.13† | 0.18* | 0.01 | 0.29*** | — | |

| 9. Perceived Discrimination | 0.26*** | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.14* | 0.17* | −0.11 | 0.30*** | 0.38*** | — |

| 10. Anxiety | 0.24*** | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.20** | 0.29*** | 0.23** | 0.36*** |

Note. † p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .005.

Relevant to study hypotheses, correlation analyses showed significant, positive correlations between perceived discrimination and anxiety (r = .36, p < .001). COVID‐19 was correlated with negative Chinese media exposure (r = .17, p = .016), and negative Chinese media exposure was correlated with both perceived discrimination (r = .38, p < .001) and anxiety (r = .23, p = .0012).

T‐Tests comparing the Pre‐ and During‐COVID groups

Participants in the Pre‐ and During‐COVID groups did not significantly differ in age or parental education (all ps > .10), or nor did they differ by generational statuses. However, participants in the During‐COVID sample had resided in the United States slightly longer than participants in the Pre‐COVID sample on average (15.74 and 13.74 years, respectively; t(196) = −1.73, p = .085). The During‐COVID sample was comprised of a significantly greater proportion of male participants (64.1% compared to 42.2%); χ 2(1) = 11.43, p = .0007), which was consistent with the recruitment effort to oversample male students during the spring semester to reach a gender‐balanced sample. Relevant to study aims, the During‐COVID group (M = 1.96) reported significantly greater perceived discrimination than the Pre‐COVID group (M = 1.68; t(196) = −3.77, p = .00022). The During‐COVID group also endorsed greater anxiety symptoms (M = 15.9) compared to the Pre‐COVID group (M = 10.3, t(195) = −3.40, p = .00083).

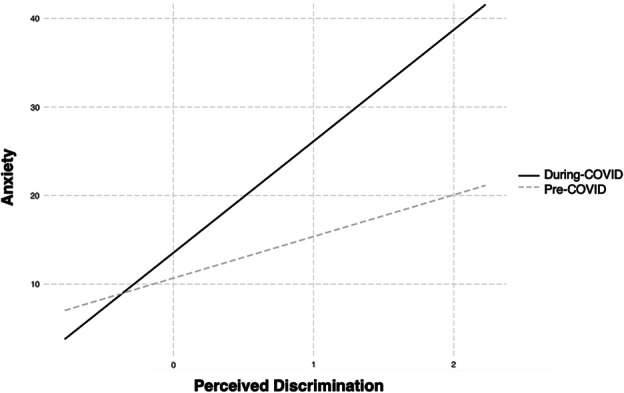

Regression model testing COVID‐19 as a moderator of perceived discrimination and anxiety

The data showed no evidence of multicollinearity, and no outliers were identified. As shown in Table 3, perceived discrimination was a significant predictor (β = 0.21, p = .009) of concurrent anxiety. With perceived discrimination in the model, COVID‐19 was only a marginally significant predictor of anxiety (β = 0.12, p = .083). The interaction term (perceived discrimination X COVID‐19) was significant in predicting anxiety (β = 0.36, p = .016). The significant interaction was probed with simple slope analyses at values Pre‐ and During‐COVID (see Figure 2). Perceived discrimination was significantly related to concurrent anxiety both pre‐ and post‐COVID‐19. However, the During‐COVID regression showed steeper slopes (β = 0.55, p < .001) compared to Pre‐COVID (β = 0.21, p = .01).

TABLE 3.

Regression model predicting anxiety from perceived discrimination, COVID‐19, and their interaction

| Dependent variable: Anxiety | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B (SEB) | β |

| Perceived discrimination | 4.70 (1.79) | .21** |

| COVID | 2.86 (1.65) | .12† |

| Perceived discrimination*COVID | 7.88 (3.23) | .36* |

| Total R 2 | .17*** | |

Note. † p < .10; * p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .005; B = unstandardised regression coefficient; SE B = standard error of the coefficient; β = standardised coefficient.

Figure 2.

Interaction plot of simple slopes for associations between perceived discrimination and anxiety at values Pre‐ and During‐COVID.

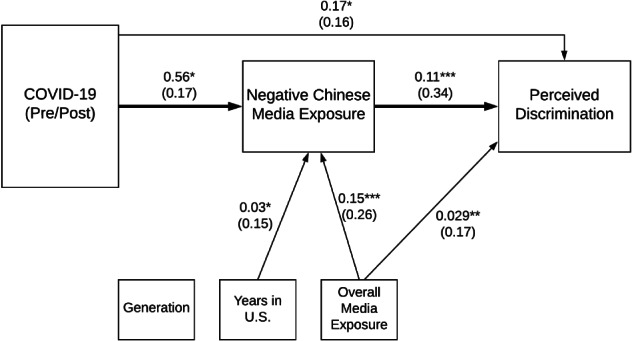

Path analyses testing relations of COVID‐19 to negative Chinese media exposure to perceived discrimination and anxiety

In the tested path analytic model (Figure 3), the effect of overall media exposure on all dependent variables was controlled. The effect of generation on perceived discrimination was controlled, and the effect of years in United States on both negative Chinese media exposure and perceived discrimination was controlled. The model fit the data well (χ 2(df = 3, N = 196) = 0.298, p = .96, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, SRMR = .006). In terms of covariates, greater overall media exposure was associated with significantly greater negative Chinese media exposure (β = .26, p < .001) and perceived discrimination (β = .17, p = .008). Greater years in the United States was significantly associated with greater negative Chinese media exposure (β = .15, p = .027). Years in the United States and generation status showed no significant relations with perceived discrimination. Controlling for covariates, COVID‐19 was associated with greater negative Chinese media exposure (β = .17, p = .021), which in turn was associated with significantly greater perceived discrimination (β = .34, p < .001). COVID‐19 also showed a significant direct relationship with perceived discrimination (β = .16, p = .016).

Figure 3.

Path analytic model testing relations from COVID‐19 to negative Chinese media exposure, and from negative Chinese media exposure to perceived discrimination, controlling for covariates. Only significant paths are shown, with the unstandardised path coefficients and the standardised path coefficients in parentheses. The significant indirect path is shown in bold. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .005.

To examine the hypothesised indirect (i.e., mediated) association (i.e., COVID‐19 ➔ negative Chinese media exposure ➔ perceived discrimination), the bias‐corrected bootstrap confidence interval (CI) method was used (MacKinnon et al., 2004). According to this approach, a 95% confidence interval that does not contain zero indicates a statistically significant indirect effect. Results showed a significant indirect path from COVID‐19 to perceived discrimination via negative Chinese media exposure (estimate = 0.060, 95% CI = [0.010, 0.146]).

In sensitivity analyses excluding international students (N = 41) from our sample, results on all three aims did not change in terms of significance or directionality.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the psychosocial effects of COVID‐19 pandemic on Chinese American college students. Our findings showed that students who participated in the study during COVID‐19 pandemic endorsed significantly greater perceived discrimination and anxiety symptoms compared to students who participated before COVID‐19. Perceived discrimination was related to concurrent anxiety symptoms, and this relationship was stronger in the context of COVID‐19. In addition, negative Chinese media exposure partially mediated the association between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination.

As expected, the onset of COVID‐19 pandemic was associated with both increased perceived discrimination and increased reports of anxiety symptoms. The finding of increased perceived discrimination among Chinese American college students after COVID‐19 corroborates news reports of increased discrimination directed towards Chinese Americans (Tavernise & Oppel, 2020). Factors such as the disease threat of COVID‐19 or supply shortages may account for COVID‐related increases in anxiety levels (American Psychiatric Association, 2020). Notably, approximately a third of participants in the present sample were international students from China, and the rest of participants were second‐ and third‐generation Chinese American students, who likely also had familial ties to China. Thus, anxiety for these students may have been highly linked to concerns for international travel home or fear of relatives becoming infected from the initial outbreak in China. Overall, our results are consistent with widely reported increases in anxiety after COVID‐19 (American Psychiatric Association, 2020).

The finding that relations between perceived discrimination and anxiety were stronger for students who participated during the COVID‐19 pandemic is consistent with the IRR model, which proposes that individual outcomes for immigrant and ethnic minority youth can be influenced by broader, global events (Suárez‐Orozco et al., 2018). There are several reasons why the COVID‐19 pandemic may have strengthened the detrimental influence of perceived discrimination on mental health in this sample. First, objective spikes in reported incidences of anti‐Asian hate crimes (Gover et al., 2020) could render subjective interpretations of discrimination more psychologically potent and harmful. Second, research has suggested that contextual factors can alter the effectiveness of strategies used to cope with discrimination, such as when discrimination is experienced at the wider societal as opposed to individual level (Perez & Soto, 2011). The present study took place during the first few months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, and so participants might still have been adapting to cope with instances of anti‐Chinese discrimination in society at large. Furthermore, with social distancing measures and the cancellation of social events, the pandemic may have reduced access to social support resources that typically buffer the negative effects of perceived discrimination. Another reason perceived discrimination may have shown stronger ties to anxiety during the pandemic is because of a general hypervigilance to threat. Hypervigilance is a common reaction to infectious disease outbreak (American Psychiatric Association, 2020), and could have contributed to a general negativity bias that pervaded self‐reports of both perceived discrimination and anxiety in our sample. Finally, the context of COVID‐19 represents increased instances of discrimination perceived from online sources (Timberg & Chiu, 2020), which can potentially have stronger ties with anxiety. Images and articles with discriminatory content on the internet can be viewed repeatedly, which may increase rumination and resulting internalising symptoms (Umaña‐Taylor et al., 2015). In sum, our hypothesis that the context of COVID‐19 pandemic moderated associations between perceived discrimination and anxiety was confirmed. However, further research is needed on how coping strategies and access to coping resources change during major global events such as the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The relation between the COVID‐19 pandemic and perceived discrimination was partially mediated by exposure to media that negatively portrayed Chinese individuals. This pattern held even while controlling for overall media exposure, suggesting that the content of media may be influential above and beyond the frequency of media consumption. These results generally align with studies of previous infectious diseases (e.g., the 2003 SARS epidemic, the 2014 Ebola outbreak) where media content was found to play a role in stigmatising certain racial and ethnic groups (Eichelberger, 2007; Monson, 2017). Because both media exposure and perceived discrimination measures were self‐reported, the general hypervigilance to threat prompted by the COVID‐19 pandemic may partially account for their positive associations. In order to confirm the role of negative Chinese media exposure in the link between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination, it will be important for future studies to include more objective, rigorous measures of media exposure and media framing.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the study was cross‐sectional and not initially designed to investigate the psychosocial effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Thus, the direction of relations among constructs cannot be inferred. Although media is examined as one pathway by which COVID‐19 may influence perceived discrimination, there are many other variables that could account for these associations that we did not measure. Future research can use experimental designs to examine the impact of biased media exposure on perceived discrimination. While we conceptualise perceived discrimination as an outcome of negative Chinese media exposure, it is possible that these variables have bidirectional relationships. Second, all variables were measured via participants' self‐report. Shared method variance may cause an overestimate of the strength of associations between variables, especially in the context of COVID‐19 where hypervigilance to threat may lead to a negativity bias in reporting. Another measurement limitation is that the internal consistency of the overall media exposure variable was low, and negative Chinese media exposure was measured by only one item. This item may capture wider anti‐China discourse not necessarily related to Chinese Americans, and does not reveal nuances in the type of media source. Thus, future studies may consider employing more experimental or detailed, objective measures of media exposure. In addition, the first‐generation or international students in our sample may have been more likely to be exposed to Chinese media—future studies should consider exploring whether the media exposure of international and domestic students differ, and implications for perceived discrimination and anxiety. Third, participants in the present sample attended a public university with a relatively high density of Chinese students (approximately 17%). This setting may increase the rate of intergroup contact leading to escalations in perceived discrimination, or it may entail access to more social support and resources. Thus, the findings might not generalise to other college student samples. Finally, the During‐COVID group were assessed during the first 3 months of COVID‐19 pandemic (between January 2020 and mid‐March 2020), when university closures and “shelter‐in‐place” orders were first implemented. Our findings on linkages between COVID‐19 and perceived discrimination and anxiety may therefore be underestimates, as these relations may have become stronger as the pandemic progressed. Conversely, our findings may overestimate the role of COVID‐19 given that the period of initial outbreak entailed more uncertainty and potentially stronger psychosocial reactions.

Despite these limitations, the present study has several strengths. The study used a quasi‐experimental design by comparing samples from pre‐ and during‐COVID‐19 in the same study. Moreover, our focus on CA young adults is relevant given the pandemic's initial start in China and the resulting discrimination reported worldwide that was specifically directed at Chinese individuals. Our findings suggest that college student counsellors should consider the role of perceived discrimination in supporting the mental health of Chinese American college students, especially in the context of COVID‐19. Given the salience of media exposure in the present study, colleges might also consider media as an avenue to provide psychoeducation, social support and resources to these students to counteract discrimination's psychological effects. Interventions can also target the pattern and content of college students' media use to help them process negative media messages constructively. Overall, this study adds to a growing body of literature highlighting the need to better understand precursors to Asian American youth's mental health, which is an area that is often overlooked.

Although the design of the present study limits the formation of any causal conclusions, our results suggest several avenues for future research. This study highlights the role of the broader context in studying discrimination and mental health. As international migration continues to occur at unprecedented rates with implications for global policy, understanding how macrolevel contextual factors influence the discrimination to adjustment link is paramount. Longitudinal research on the public mental health implications of the COVID‐19 pandemic might also consider exploring factors that moderate the association between perceived discrimination and anxiety in the context of COVID‐19. The present study suggests that the content of media may contribute to COVID‐related increases in perceived discrimination, and future studies may consider using content analysis to specify the media content and sources that are most harmful. The COVID‐19 pandemic is likely to have reverberating psychosocial consequences, and understanding these effects will be critical in supporting the mental health of Chinese American college students and the population at large.

SH and QZ collaborated on study design, data collection, and analytic plan. SH consulted with QZ to analyse and interpret the data. SH initially drafted the manuscript, and QZ critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. This study was supported by an award from the Sheldon Zedeck Program for Culture, Behaviour and Management Study at the University of California Berkeley.

REFERENCES

- Althaus, S. L. , & Tewksbury, D. H. (2007). Toward a new generation of media use measures for the ANES. Report to the Board of Overseers of the ANES, 1, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2020). New poll: COVID‐19 impacting mental well‐being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news‐releases/new‐poll‐covid‐19‐impacting‐mental‐well‐being‐americans‐feeling‐anxious‐especially‐for‐loved‐ones‐older‐adults‐are‐less‐anxious

- Asian American Journalists Association . (2020). AAJA calls on news organizations to exercise Care in Coverage of the coronavirus outbreak. Asian American Journalists Association. https://www.aaja.org/guidance_on_coronavirus_coverage [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A. D. , & Kim, S. Y. (2009). Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1682–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. Readings on the Development of Children, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar, D. , Shannon, G. , Bhopal, S. S. , & Abubakar, I. (2020). Racism and discrimination in COVID‐19 responses. Lancet (London, England), 395(10231), 1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelberger, L. (2007). SARS and New York's Chinatown: The politics of risk and blame during an epidemic of fear. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1284–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover, A. R. , Harper, S. B. , & Langton, L. (2020). Anti‐Asian hate crime during the CoViD‐19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Juang, L. P. , Shen, Y. , Costigan, C. L. , & Hou, Y. (2018). Time‐varying associations of racial discrimination and adjustment among Chinese‐heritage adolescents in the United States and Canada. Development and Psychopathology, 30(5), 1661–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D. P. , Lockwood, C. M. , & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson, S. (2017). Ebola as African: American media discourses of panic and otherization. Africa Today, 63(3), 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, M. , & Shanahan, J. (2010). The state of cultivation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 54(2), 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. (2019). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User's guide, 5.

- Pappas, G. , Kiriaze, I. J. , Giannakis, P. , & Falagas, M. E. (2009). Psychosocial consequences of infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 15(8), 743–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez, C. R. , & Soto, J. A. (2011). Cognitive reappraisal in the context of oppression: Implications for psychological functioning. Emotion, 11(3), 675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, K. A. (2011). Framing Islam: An analysis of US media coverage of terrorism since 9/11. Communication Studies, 62(1), 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J. , Shen, B. , Zhao, M. , Wang, Z. , Xie, B. , & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID‐19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasubramanian, S. (2011). The impact of stereotypical versus counterstereotypical media exemplars on racial attitudes, causal attributions, and support for affirmative action. Communication Research, 38(4), 497–516. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M. T. , Branscombe, N. R. , Postmes, T. , & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well‐being: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, E. K. , & Douglass, S. (2014). School diversity and racial discrimination among African‐American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez‐Orozco, C. , Motti‐Stefanidi, F. , Marks, A. , & Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant‐origin children and youth. American Psychologist, 73(6), 781–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed, M. , & Juan, M. J. D. (2012). Discrimination and psychological distress: Examining the moderating role of social context in a nationally representative sample of Asian American adults. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tavernise, S. , & Oppel, R. (2020). Spit on, yelled at, attacked: Chinese‐Americans fear for their safety. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese‐coronavirus‐racist‐attacks.html [Google Scholar]

- Timberg, C. , & Chiu, A. (2020). As the coronavirus spreads, so does online racism targeting Asians, new research shows. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/04/08/coronavirus‐spreads‐so‐does‐online‐racism‐targeting‐asians‐new‐research‐shows/ [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. , Tynes, B. M. , Toomey, R. B. , Williams, D. R. , & Mitchell, K. J. (2015). Latino adolescents' perceived discrimination in online and offline settings: An examination of cultural risk and protective factors. Developmental Psychology, 51(1), 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R. , Yu, Y. , Jackson, J. S. , & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio‐economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]