Abstract

Background

Environmental adaptation and expanding harvest seasons are primary goals of most peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] breeding programs. Breeding perennial crops is a challenging task due to their long breeding cycles and large tree size. Pedigree-based analysis using pedigreed families followed by haplotype construction creates a platform for QTL and marker identification, validation, and the use of marker-assisted selection in breeding programs.

Results

Phenotypic data of seven F1 low to medium chill full-sib families were collected over 2 years at two locations and genotyped using the 9 K SNP Illumina array. Three QTLs were discovered for bloom date (BD) and mapped on linkage group 1 (LG1) (172–182 cM), LG4 (48–54 cM), and LG7 (62–70 cM), explaining 17–54%, 11–55%, and 11–18% of the phenotypic variance, respectively. The QTL for ripening date (RD) and fruit development period (FDP) on LG4 was co-localized at the central part of LG4 (40–46 cM) and explained between 40 and 75% of the phenotypic variance. Haplotype analyses revealed SNP haplotypes and predictive SNP marker(s) associated with desired QTL alleles and the presence of multiple functional alleles with different effects for a single locus for RD and FDP.

Conclusions

A multiple pedigree-linked families approach validated major QTLs for the three key phenological traits which were reported in previous studies across diverse materials, geographical distributions, and QTL mapping methods. Haplotype characterization of these genomic regions differentiates this study from the previous QTL studies. Our results will provide the peach breeder with the haplotypes for three BD QTLs and one RD/FDP QTL to create predictive DNA-based molecular marker tests to select parents and/or seedlings that have desired QTL alleles and cull unwanted genotypes in early seedling stages.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-021-07483-8.

Keywords: FlexQTL, Prunus persica QTL, Haplotype, Pedigree-based analysis, Bloom date, Ripening date, Fruit development period

Background

Peaches and nectarines [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] are deciduous fruit trees belonging to the Rosaceae family. These are native to China and grown throughout the world in a wide range of environments. The gross production value of peaches and nectarines in 2016 was $825 million in the United States and $17,107 million globally [1].

Breeding of woody perennial crops is not an easy task since their long juvenility periods and large plant size makes maintaining large populations in the field expensive [2]. The use of marker-assisted breeding (MAB) provides a tool to do an early selection of seedlings, identify superior parents, improve the selection of elite alleles for essential traits, and stack desirable alleles [3, 4]. This strategy is pertinent for perennial fruit tree to reduce breeding operational costs [3].

QTL identification in peaches conducted [5] for acidity, total sugar content, organic acids, fruit weight, bloom, and harvest dates [6, 7], and chilling injury susceptibility [8] have been limited due to the low marker density of genetic maps [9]. Recently, these issues have been overcome due to the availability of the peach genome v1.0 and v2.0 [10, 11] sequence and the development of the International Peach SNP Consortium peach 9 K SNP array [11]. Moreover,

the Pedigree-Based Analysis (PBA) approach [12, 13] that uses multiple pedigree-linked families allows the discovery of more QTL or QTL-alleles per locus across a range of genetic backgrounds. This approach has facilitated the identification of QTLs for blush [14–16], ripening date [15, 17, 18], soluble solids content [15–18], fruit weight, and titratable acidity [15, 17, 19].

Bloom date, which is primarily determined by chilling requirement [20–22], is an important trait determining peach adaptation for both low and high chill zones. Bloom date has been reported as moderately to a highly heritable trait (0.39–0.92) [15, 23–27]. QTLs for bloom date were reported on LG1 (40–60% of phenotypic variance (PVE)), LG2 (27% PVE), LG4 (32–35% PVE) and LG7 (21% PVE). Not all the QTLs were found in all the studies indicating the population-specific nature of these QTLs [15, 17, 28–30].

Ripening date in peach trees is a crucial element for extending the production season and developing cultivars that ripen throughout the harvest season. Also, the ripening process is involved in the regulation of several metabolic pathways such as blush, sugar/acid balance, and the flesh softening in peach fruits [31]. Narrow sense heritability (h2) for ripening date ranges from high to very high (0.79–0.94) [15, 32, 33]. The major QTL for controlling RD was mapped on LG 4 at ~ 44 cM in the Prunus T × E reference map, and a putative candidate gene was located at ~ 10.5 Mbp on the peach genome sequence v.1 [30, 31, 34, 35]. This QTL explained ~ 50 to 98% of the phenotypic variability. The RosBREED project has verified this locus is significant in the U.S. breeding programs [18]. Likewise, a QTL for RD on chromosome 4 was detected in apricot, sweet cherry [31], and almond [36].

Fruit development period (FDP) is the period between bloom and ripening dates [37], and is well correlated with RD [6, 15]. This trait is highly heritable (h2 = 0.73–0.98) [15, 23, 26, 38]. QTLs for fruit development period were mapped on LGs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 with decisive evidence. The QTLs mapped by Hernández Mora, et al. [15] on LGs 1–6 and by Etienne, et al. [6] on LG4 co-localized with ripening date QTLs.

Currently, DNA-based tests for a few breeding-relevant traits have been developed and used in the peach marker-assisted selection application, including maturity date (G4mat) [39], quality traits, and fruit bacterial spot resistance. Thus, work is needed to develop DNA tests for BD and FDP traits and to validate SNP-based DNA test (G4mat) for ripening date to enable their use in the TX and other breeding programs [3, 40–42].

The objectives of this study are to identify new and/or validate the major QTLs previously reported for bloom date, ripening date, and fruit development period through pedigree-based analysis approach (PBA) using Texas peach/nectarine germplasm. Also, to estimate QTL genotypes for important breeding parents and to identify predictive SNP marker(s) associated with desired QTL alleles. Results from this research will facilitate the design of DNA tests linked to these QTL(s) or genes for routine use for marker-assisted breeding.

Results

Phenotypic data analysis

The mean BD value ranged from 42.3 ± 3.9 (CA11) to 50.2 ± 9.45 (TX13), and a maximum range of 51, with the number of observations between 82 in CA11 and 143 in overall mean (Additional file 1: Table S1). In our study, BD distribution varied across environments and overall mean (Additional file 2: Fig. S1). The CA environments were skewed towards the lower values, whereas the TX exhibited multimodal profiles with two or more peaks in both environments. This was expected as some of the higher chill genotypes had delayed bloom in the lower chill Texas site compared to California (~ 540 vs. ~ 1090 chilling hours) [43]. Normal distribution was seen in the overall mean of BD.

RD exhibited an average between 129.2 ± 16.7 (TX12) and 157.4 ± 17.7 (CA11), with greater (87.0) and lower (59.5) RD ranges in the overall mean and TX13 data sets, respectively. CA and the overall mean data sets were slightly skewed towards the higher values, while the TX data sets were skewed towards the lower values. On average, fruit ripened approximately 17 days later at Fowler, CA than at College Station, TX. FDP mean values ranged from 81.2 ± 16.9 (TX12) and 115.3 ± 16. 9 (CA11) with FDP range from ~ 67 (CA12) to 91 (TX13) days. The minimum number of observations (59) was recorded for CA11 compared to 138 observations for the CA12 and overall mean data sets. Similar to RD, FDP for CA data sets were slightly skewed towards higher values compared to the TX environments, which skewed towards lower values while the overall mean showed normal distribution. Fruit had development periods that were 23 days longer, on average, at Fowler, CA, than at College Station, TX. This was an effect of cooler temperatures during early fruit development in March and April for CA11 and CA12 (~ 15 and 9 °C) relative to TX12 and TX13 (21 and 18 °C).

Among these traits, a strong correlation was found between RD and FDP (r = 0.91) (Additional file 1: Table S2), and a moderately weak correlation was observed between FDP and BD (− 0.45). The negative correlations between BD and FDP suggest that the earlier blooming genotypes experience a delay in the rate of fruit development due to cooler temperatures. A weak correlation was found between RD and BD traits (− 0.14).

Genotype by environment interactions

The genotype × environment interaction (G × E) is the differential sensitivity of genotypes to different environments. If such interaction exists, the selection would be complicated and result in genetic gains reduction in a breeding program. Understanding the G × E interactions is key to increasing the efficiency of marker-assisted selection for complex traits [44].

In this study, RD and FDP showed very high broad-sense heritability (H2 = 0.95 and 0.96, respectively), strong correlations among environments (r = 0.91), and minimal G × E variance ( ratio = 0.20) (Additional file 1: Table S3 and S4) whereas BD trait, showed highbroad-sense heritability (H2 = 0.88), strong correlation among environments (r = 0.83) and a moderate genotype by environment interaction ( 0.70). All traits had comparable PC2 values and ranged from 5.5 to 6.8 (Additional file 1: Table S5), implying that the environments equally discriminate the populations for these traits. Finally, the minimal G × E effect of RD and FDP is supported by the relatively similar length of the environmental vectors in the GGE biplots, especially within the same location, indicating a high correlation among them and equal discriminatory ability of the four environments (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). Also, the distance between the environmental vectors was closer between CA11 and CA12, and between TX12 and TX13 for RD and FDP, respectively, illustrate that genotypes responded similarly in these two environments. This is confirmed by the highest positive correlations between CA11 and CA12 (r = 0.87, RD and 0.84, FDP) and between TX12 and TX13 (r = 0.79, RD and 0.89, FDP) for RD and FDP) (see Additional file 1: Table S4).

For BD, the sharper angle and less distance were observed between CA12 and TX12, TX12 and TX13, and CA12 with TX13 (Additional file 2: Fig. S2), indicating a stronger correlation between these environments (r = 0.73, 0.75, and 0.65) (Additional file 1: Table S4). The best discrimination of BD among genotypes was observed in the CA11 environment indicated by the longer vectors for these environments (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). Also, the environment CA11 was far from the other three environments and showed less correlation coefficient. However, the low number of observations of this environment (82) may have affected the correlation and G × E results.

Genome-wide QTL analysis

The narrow-sense heritability (h2) varied among datasets in each trait. Minimum h2 (0.44) for BD was observed in BD-CA11 versus maximum observed h2 (0.82) in BD-mean (Table 1). While for RD, h2 ranged from 0.59 (RD-TX13) to 0.83 (RD-CA12), and for FDP, the minimal h2 was observed in FDP-CA11 (0.65) and the maximal in FDP-CA12 (0.82).

Table 1.

QTLs mapped for the bloom date (BD), ripening date (RD), and fruit development period (FDP) traits evaluated in four environments (CA11, CA12, TX12, and TX13), and the overall mean for 143 peach seedlings

| 2ln(BF) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | MCMC | Records | μ | σ2p | σ2e | σ2A | h2 | LG | 1/0 | 2/1 | 3/2 |

| BD-CA11 | 150,000 | 82 | 42.3 | 15.2 | 8.5 | 6.7 | 0.44 | 1 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| BD-CA12 | 250,000 | 138 | 43.8 | 10.5 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 0.79 | 1 | 11.4 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| 4 | 10.4 | 0.3 | −0.5 | ||||||||

| 7 | 29.5 | 1.0 | −0.1 | ||||||||

| BD-TX12 | 150,000 | 114 | 49.3 | 76.3 | 23.5 | 52.9 | 0.69 | 1 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| 4 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| 7 | 15.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ||||||||

| BD-TX13 | 150,000 | 124 | 50.2 | 89.3 | 23.5 | 65.7 | 0.74 | 1 | 14.1 | −0.4 | −0.3 |

| 4 | 29.6 | −1.3 | na | ||||||||

| BD-mean | 3600,000 | 143 | 47.0 | 42.6 | 7.6 | 35.1 | 0.82 | 1 | 13.9 | 5.5 | −1.2 |

| 4 | 4.6 | −2.0 | na | ||||||||

| 7 | 14.6 | −0.9 | na | ||||||||

| RD-CA11 | 100,000 | 104 | 157.4 | 313.9 | 97.6 | 216.3 | 0.69 | 4 | 28.0 | 3.9 | 0.6 |

| RD-CA12 | 200,000 | 138 | 147.3 | 239.0 | 41.5 | 197.5 | 0.83 | 4 | na | 18.6 | 0.2 |

| RD-TX12 | 100,000 | 94 | 129.2 | 278.8 | 112.6 | 166.1 | 0.60 | 4 | 29.3 | 0.6 | −0.4 |

| 7 | 2.3 | 0.2 | na | ||||||||

| RD-TX13 | 500,000 | 114 | 141.8 | 293.7 | 119.8 | 173.8 | 0.59 | 4 | 27.6 | 4.5 | 0.7 |

| RD-mean | 100,000 | 135 | 142.9 | 187.9 | 67.4 | 120.5 | 0.64 | 4 | na | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| FDP-CA11 | 100,000 | 59 | 115.3 | 285.2 | 97.7 | 185.7 | 0.65 | 4 | 27.0 | 4.4 | 1.1 |

| FDP-CA12 | 100,000 | 138 | 103.5 | 249.9 | 46.2 | 203.1 | 0.82 | 4 | na | 30.9 | 0.3 |

| FDP-TX12 | 250,000 | 94 | 81.2 | 286.5 | 91.6 | 194.8 | 0.68 | 4 | 29.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||||||

| FDP-TX13 | 150,000 | 114 | 91.3 | 321.0 | 105.5 | 215.4 | 0.67 | 4 | 28.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 |

| FDP-mean | 100,000 | 138 | 95.5 | 246.4 | 71.7 | 174.7 | 0.71 | 4 | na | 11.7 | 1.8 |

Bloom date, ripening date, and fruit development period in Julian days

CA11 Fowler, California 2011, CA12 Fowler, California 2012, TX12 College Station, Texas 2012, TX13 College Station, Texas 2013

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) run length, phenotypic mean (μ), phenotypic variance (σ2P), residual variance(σ2e), additive variance(σ2A), narrow-sense heritability (h2), the linkage groups (LG) that QTLs were mapped on

2ln(BF). Bayes Factor, a measure quantifies the support from the data for the number of QTLs in the model (QTL evidence), after pair-wise model comparison (1/0, 2/1, and 3/2) such as ‘one-QTL model’ vs. ‘zero-QTL

Three QTLs were mapped for BD on three linkage groups (LG1, 4, and 7) across the four environments (site × year combinations) and their overall mean. The QTL on LG1 was at the distal end and showed strong to decisive evidence in all data sets (Table 1 and Additional file 2: Fig. S3). The QTL on LG4 was mapped in three environments (except CA11) and the overall analysis, showing positive and decisive evidence. At the same time, the QTL on LG7 was seen in only two environments and the overall analysis with decisive evidence. FlexQTL software found one to two candidate QTLs for RD and FDP depending on the environment; however, only the QTL on the middle part of G4 passed our inclusion criteria. (Table 1 and Additional file 2: Fig. S4 and S5).

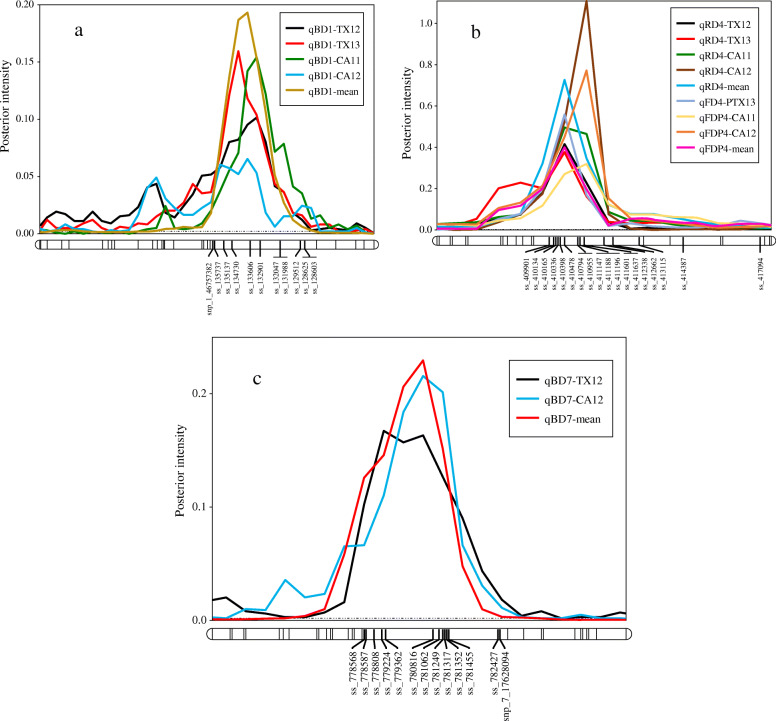

For BD, the proportion of phenotypic variation explained (PVE) ranged from 17 to 54%, 11 to 55%, 11 to 18% for LG1, LG4, and LG7, respectively (Table 2). The highest posterior QTL intensity (0.96) showed in LG1 for BD-mean, and the lowest intensity (0.21) was found in LG4 for BD-TX12. The highest additive effect (~ 10 days) was in LG4 for BD-TX13, and the lowest (~ 2 days) showed in LG1, 4, and 7 for BD-CA12. The QTL on LG1 was co-localized across all data sets with an interval between 172 and 182 cM (peaks, 174, 176, and 178 cM), and the physical position of this chromosomal region was 43,058,300 - 45,586,061 bp on the peach genome sequence v2.0, (Table 2, Fig. 1a, and Additional file 1: Table S6). Likewise, peaks of QTL on LG4 of three data sets, except CA12, clustered at mode 50 cM, with an interval between 48 and 54 cM and physical chromosomal position between 11,956,738 – 13,633,831 bp. Regarding LG7, the peaks co-localized at either 64 or 66 cM with an interval from 62 to 70 cM and physical chromosomal position between 15,513,277 - 17,226,623 bp on the peach genome sequence v2.0 (Table 2 and Fig. 1b, Additional file 1: Table S6).

Table 2.

QTL name, linkage group, interval, mode peak, intensity, additive effect, and phenotypic variance explained (PVE) for the bloom date (BD), ripening date (RD), and fruit development period (FDP) traits evaluated in four environments (CA11, CA12, TX12, and TX13), and the overall mean for 143 peach seedlings

| QTL name | Linkage Group | Interval (cM) | Mode peak (cM) | Intensity | Additive Effect (d) | PVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qBD1-CA11 | 1 | [174, 182] | 178 | 0.94 | 5 | 54 |

| qBD1-CA12 | 1 | [172, 180] | 176 | 0.43 | 2 | 19 |

| qBD1-TX12 | 1 | [172, 182] | 178 | 0.72 | 5 | 17 |

| qBD1-TX13 | 1 | [172, 182] | 174 | 0.86 | 6 | 20 |

| qBD1-mean | 1 | [172, 182] | 178 | 0.96 | 5 | 35 |

| qBD4-CA12 | 4 | [70, 78] | 76 | 0.60 | 2 | 18 |

| qBD4-TX12 | 4 | [48, 52] | 50 | 0.21 | 4 | 11 |

| qBD4-TX13 | 4 | [48, 52] | 50 | 0.85 | 10 | 55 |

| qBD4-mean | 4 | [48, 54] | 50 | 0.42 | 4 | 14 |

| qBD7-CA12 | 7 | [62, 70] | 66 | 0.87 | 2 | 17 |

| qBD7-TX12 | 7 | [62, 70] | 64 | 0.89 | 5 | 18 |

| qBD7-mean | 7 | [62, 68] | 66 | 0.91 | 3 | 11 |

| qRD4-CA11 | 4 | [42, 46] | 44 | 1.40 | 17 | 46 |

| qRD4-CA12 | 4 | [42, 46] | 45 | 1.80 | 19 | 75 |

| qRD4-TX12 | 4 | [42, 46] | 44 | 0.85 | 18 | 54 |

| qRD4-TX13 | 4 | [40, 46] | 44 | 1.21 | 17 | 52 |

| qRD4-mean | 4 | [42, 46] | 44 | 1.50 | 17 | 57 |

| qFDP4-CA11 | 4 | [42, 46] | 45 | 1.10 | 16 | 42 |

| qFDP4-CA12 | 4 | [42, 46] | 45 | 1.60 | 19 | 71 |

| qFDP4-TX12 | 4 | [46, 52] | 50 | 0.79 | 18 | 56 |

| qFDP4-TX13 | 4 | [42, 46] | 44 | 1.10 | 20 | 62 |

| qFDP4-mean | 4 | [40, 46] | 44 | 1.04 | 14 | 40 |

Bloom date, ripening date, and fruit development period in Julian days

CA11 Fowler, California 2011, CA12 Fowler, California 2012, TX12 College Station, Texas 2012, TX13 College Station, Texas 2013

Posterior intensity is the accumulated probability of QTL presence in a successive series of 2 cM bins (chromosome segments) based on Bayesian analysis

For each QTL reported, the evidence [2ln(BF)] is either positive (2–5), strong (5–10), or decisive (> 10)

Fig. 1.

Position of putative QTLs and peaks controlling the bloom date (BD) in peach at linkage group 1 (LG1) a and LG7 b and the ripening date (RD) and fruit development period (FDP) at LG4 c from four environments (CA11, CA12, TX12, TX13), and the overall combined mean generated using MapChart software [45]. CA11, CA12 = Fowler, California 2011 and 2012; TX12, TX13 = College Station, Texas 2012 and 2013

The proportion of phenotypic variation explained by RD QTL on LG4 ranged between 46 and 75% (Table 2). The highest posterior QTL intensity (1.80) and the highest additive effect (~ 19 days) were found in CA12. In most environments, the observed high intensity (greater than one) implies that FlexQTL assigned two QTLs within the same QTL interval with an average distance between them of 1.0 cM across all sampled models. This distance is very short to be genetically meaningful for population sizes. This QTL had mode at either 44 or 45 cM, overlapping intervals from 40 to 46 cM across all data sets, and the physical chromosomal position between 10,396,616 to 11,298,736 on the peach genome sequence v2.0 (Table 2, Fig. 1c, and Additional file 1: Table S6). The proportion of phenotypic variation explained by FDP QTL on LG4 ranged between 40 and 71% (Table 2). The highest posterior QTL intensity (1.60) was for CA12 and the lowest (0.79) for TX12. The highest additive effect (~ 20 days) was found in TX13. Likewise, this QTL had a mode at either 44 or 45 cM, overlapping intervals from 40 to 46 cM across all data sets, except TX12, and has a physical chromosomal position between ~ 10,396,616 to 11,298,736 bp of the peach genome sequence v2.0 (Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S6). Like RD, the high intensity that is noticed in most data sets indicates two tightly linked QTLs within the QTL interval, and the gap between them averaged to 1.4 cM across all sampled models. So, the distance is also too short to be genetically dissected in these studied population sizes.

QTL associated haplotypes, number of QTL-alleles, their effect, predictive markers, and sources

On LG1, 11 SNPs in the predicted qBDG1 region (172.23–182.34 cM) (Additional file 1: Table S7), chosen for haplotyping, revealed eight SNP haplotypes across the seven parents in which H8 was a common haplotype (Table 3). The estimation of the diplotype effect identified families of two parents (Y434–40 and ‘Victor’) were segregating for this QTL. The results also discovered multiple Q-alleles of various effects associated with H1 to H7, and only one q-allele was linked to low phenotypic values associated with H8.

Table 3.

QTL genotypes for bloom date (BD), ripening date (RD), and fruit development period (FDP) traits for seven breeding parents, with associated linkage groups, haplotype names, the haplotype’s SNP sequences, and original sources

| Trait/LG/Pos | Parents | QTL allele | Hap. | SNP haplotype | Successive ancestors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele sequence | (founders in bold) | ||||

| BD LG1 [172.23–182.34] | Galaxy | Q ♀ | H4 | ABABBBBBAAB | Galaxy |

| Galaxy | Q ♂ | H4 | ABABBBBBAAB | Galaxy | |

| Y426–371 | Q1 ♀ | H1 | ABABBBAAAAB | Y426–371 | |

| Y426–371 | Q1 ♂ | H7 | BABBBBAAABB | Y426–371 | |

| Y434–40 | Q4 ♂ | H2 | ABABBBAAABB | Y434–40 | |

| Victor | Q ♂ | H5 | ABBBBBABBBA | Goldprince > F_Goldprince | |

| Y435–246 | Q3 ♀ | H6 | BAABBBBBAAB | Y435–246 | |

| Y435–246 | Q2 ♂ | H3 | ABABBBABBBA | Y435–246 | |

| Y434–40 | q ♀ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | Y434–40 | |

| Victor | q ♀ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | TropicBeauty > Fla3–2 | |

| TX2B136 | q ♀ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | TX2B136 | |

| TX2B136 | q ♂ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | TX2B136 | |

| TXW1490_1 | q ♀ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | TropicBeauty > Fla3–2 | |

| TXW1490_1 | q ♂ | H8 | BBABBBBBAAA | F_TXW1490_1 | |

| BD LG4 [47.83–54.54] | TX2B136 | Q ♀ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | TX2B136 |

| TX2B136 | Q ♂ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | TX2B136 | |

| TXW1490_1 | Q ♀ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | TropicBeauty > Flordaprince | |

| TXW1490_1 | Q ♂ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | F_TXW1490_1 | |

| Y426–371 | Q ♀ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | Y426–371 | |

| Victor | Q ♂ | H3 | ABAAAABBAABAB | Goldprince > F_Goldprince | |

| Y435–246 | Q ♂ | H2 | BABBBBAABBABA | Y435–246 | |

| Galaxy | Q ♂ | H2 | BABBBBAABBABA | Galaxy | |

| Y435–246 | q ♀ | H1 | BBBBBBBABAAAA | Y435–246 | |

| Y426–371 | q ♂ | H1 | BBBBBBBABAAAA | Y426–371 | |

| Galaxy | q ♀ | H1 | BBBBBBBABAAAA | Galaxy | |

| Y434–40 | q ♂ | H1 | BBBBBBBABAAAA | Y434–40 | |

| Y434–40 | q ♀ | H4 | ABBBBBBABAAAA | Y434–40 | |

| Victor | q ♀ | H5 | ABBABABABBBAB | TropicBeauty > Fla3–2 | |

| BD LG7 [62.05–68.91] | Y435–246 | Q ♂ | H3 | ABAAABAABBABB | Y435–246 |

| Galaxy | Q ♀ | H6 | BBABABBABABBA | Galaxy | |

| Victor | Q ♂ | H6 | BBABABBABABBA | Goldprince > F_Goldprince | |

| TX2B136 | Q ♀ | H1 | BBABBAAAABAAB | TX2B136 | |

| Y426–371 | Q ♂ | H2 | BBABBAAAABABA | Y426–371 | |

| Y435–246 | Q ♀ | H2 | BBABBAAAABABA | Y435–246 | |

| Y434–40 | Q ♀ | H2 | BBABBAAAABABA | Y434–40 | |

| Galaxy | q ♂ | H4 | AABABBBBBABAB | Galaxy | |

| Y426–371 | q ♀ | H4 | AABABBBBBABAB | Y426–371 | |

| Y434–40 | q ♂ | H5 | AABAAAAAABABA | Y434–40 | |

| Victor | q ♀ | H7 | AABBBAAAABABA | TropicBeauty > Flordaprince | |

| TX2B136 | q ♂ | H7 | AABBBAAAABABA | TX2B136 | |

| TXW1490_1 | q ♀ | H7 | AABBBAAAABABA | TropicBeauty > Flordaprince | |

| TXW1490_1 | q ♂ | H7 | AABBBAAAABABA | F_TXW1490_1 | |

| RD and FDP LG4 [42.33–45.19] | Y426–371 | Q1 ♂ | H3 | BAAAAAAAABAAAAB | Y426–371 |

| Y434–40 | Q1 ♂ | H3 | BAAAAAAAABAAAAB | Y434–40 | |

| Galaxy | Q1 ♀ | H3 | BAAAAAAAABAAAAB | Galaxy | |

| Victor | Q2 ♀ | H4 | AAABABAABAABBBB | TropicBeauty > Fla3–2 | |

| TXW1490_1 | Q2 ♀ | H4 | AAABABAABAABBBB | TropicBeauty > Fla3–2 | |

| Y435–246 | q1 ♀ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | Y435–246 | |

| Y435–246 | q1 ♂ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | Y435–246 | |

| Y434–40 | q1 ♀ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | Y434–40 | |

| Galaxy | q1 ♂ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | Galaxy | |

| Victor | q1 ♂ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | Goldprince > F_Goldprince | |

| TX2B136 | q1 ♀ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | TX2B136 | |

| TX2B136 | q1 ♂ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | TX2B136 | |

| TXW1490_1 | q1 ♂ | H1 | ABBBBBBBBABBBBA | F_TXW1490_1 | |

| Y426–371 | q2 ♀ | H2 | BBBBBBBBBABBBBA | Y426–371 |

QTL alleles for each parent cultivar are presented with ♀ and ♂ for maternal and paternal parent sources, respectively. Parents that are heterozygous for the QTL are in bold. Allele(s) for predictive SNP marker(s) associated with Q or q-alleles for increasing or decreasing a given trait, respectively, are shown inunderscored bold. Q/q of different effect magnitude are indicated by subscript numbers. The identity of the SNP markers and their physical and genetic location is given in Additional file 1: Table S7

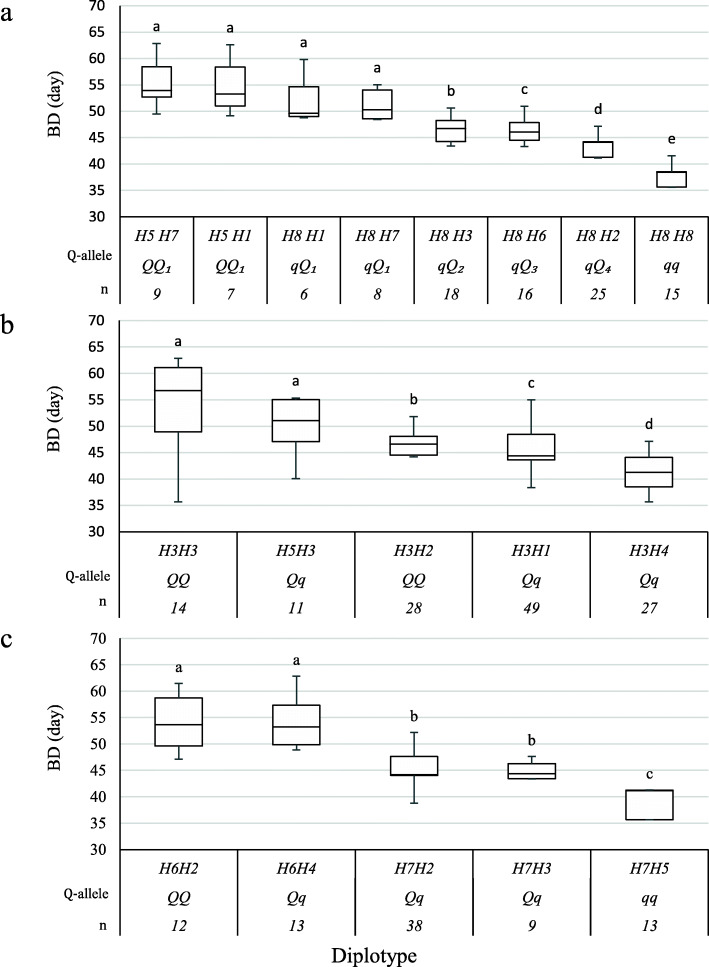

The examination of the haplotype /diplotype effects (Fig. 2a) revealed that the effect of H7 and H1could not differentiated when comparing H5H7<>H5H1 and H8H1<>H8H7. Likewise, the effects of H5 and H8 could not be differentiated when comparing H5H1 to H8H1 and H5H7 to H8H7. Also, H7 had a larger effect than H8 and H3 in the comparison H8H7<>H8H8 and H8H7<>H8H3, respectively. The effect size of H1 was greater than H2 and H3 when comparing H8H1 to H8H2 and H8H3. In general, H8 had a smaller effect than H1, H2, H3, H6, and H7, when comparing H8H8 to H8H1, H8H2, H8H3, H8H6, and H8H7. Hence, H1 and H7 had similar and the largest effects, and both coined as Q1, then followed by H3, H6, H2, and H8, which were represented as Q2, Q3, Q4, and q, respectively. However, the under-representation of QTL genotypes hindered the estimation of H4 and H5 effects.

Fig. 2.

Diplotype effect of the most common haplotypes associated with bloom date (BD) for the three QTLs mapped on LG1 a, LG4 b, and LG7 c. Means not connected by the same letter are significantly different (P < 0.05) within each linkage group. n = Diplotype sample size

All of these haplotypes could be differentiated from H8 by various pairs of adjacent SNP markers by contrasting either AB- or BA-alleles for 1) snp_1_46757382 and ss_135737 to BB of H8, or 2) ss_128625 and ss_128603 to AA of H8, and 3) ss_129512 and ss_128603 to also AA of H8 (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S7). Breeding parents ‘Galaxy’, Y426–371, Y435–246, Y434–40, and TX2B136 were considered as founders in this study and the sources of these SNPs were unknown because their ancestors were not available for genotyping. On the other hand, the Q-allele (H5) of ‘Victor’ was inherited from F_Goldprince, and the q-allele (H8) of both ‘Victor’ and TXW1490–1 was inherited from Fla3–2 through ‘TropicBeauty’.

On LG4, there were 13 SNP markers in the BD QTL region (47.83 to 54.54 cM) (Additional file 1: Table S7) selected for haplotyping. That revealed five SNP haplotypes in the seven parents. H1 and H3 were the most common haplotypes (Table 3). Families of four parents (Y435–246, Y426–371, ‘Galaxy’, and ‘Victor’) were heterozygous for this QTL. H2 and H3 were associated with the Q-allele while H1, H4, and H5 with the q-allele.

The examination of the haplotype/diplotype effects in Fig. 2b revealed that H3 was not different from H5 based on H3H3<>H5H3. Also, H3 had a larger effect than H1, H2, and H4 when comparing H3H3 to H3H1, H3H2, and H3H4, respectively. Our results suggest different effects/magnitudes of some haplotypes on BD, e.g., H5H3 (qQ) had a larger effect than H3H2 (QQ). That could be explained by several reasons such as the presence of interaction with other loci, H5 (q) having a smaller effect on decreasing BD among the other haplotypes (H1 and H4) associated with decreasing BD, or H2 (Q) having less magnitude on increasing BD. The low number of diplotype observations or high variance within a diplotype class might also have caused these issues.

More than one predictive SNP marker associated with H2 and H3 (Q- allele) were identified (Table 3). A-allele at ss_415301 (50.09 cM) along with three more SNP markers distinguished H3, whereas the A-allele at ss_414387 (48.43 cM) and the other two SNP markers were unique for H2. In contrast, H1, H4, and H5 (q-allele) were distinguished by two adjacent BB-alleles at ss_414387 and ss_415301. The H3 Q- allele was found in TX2B136, ‘Flordaprince’, F_TXW1490_1, Y426–371, and F-Goldprince while the H2 Q- allele came from Y435–246 and ‘Galaxy’. The q- alleles were found in Y435–246, Y426–371, ‘Galaxy’, Y434–40, Fla3–2, and ‘TropicBeauty’.

On LG7, the 13 SNPs (62.05–68.91 cM) in the BD QTL region (Additional file 1: Table S7) were chosen for haplotyping. Seven SNP haplotypes were discovered across the seven parents (Table 3). Estimation of the diplotype effect found families of five parents (Y426–371, Y434–40, ‘Victor’, ‘Galaxy’, and TX2B136) were segregating for this QTL. H1, H2, H3, and H6 were assigned to the Q-allele and H4, H5, and H7 to q-allele (Table 3). The analysis of the haplotype/effects showed that the effects of H2 and H4 could not be differentiated based on H6H2<>H6H4, and the same was observed between H2 and H3 when comparing H7H2 <>H7H3 (Fig. 2c). H6 had a greater effect than H7 in the comparison H6H2 to H7H2. While H5 showed a smaller effect than H2 and H3 when comparing H7H5 to both H7H2 and H7H3, respectively. Likewise, the different effects of haplotypes were noticed in this QTL for the same reasons mentioned earlier. The A-allele at the SNP marker ss_778808 (15.6 Mb, 62.48 cM) (Table 3) was associated with Q-alleles. This SNP allele inherited from the parents ‘Galaxy’, Y426–371, Y435–246, Y434–40, and TX2B136. The sources of q- allele came from F_TXW1490_1, ‘Galaxy’, Y426–371, Y434–40, TX2B136, and from ‘Flordaprince’ through ‘TropicBeauty’.

15 SNP markers in the predictive QTL region for both RD and FDP traits (42.33 to 45.19 cM) (Additional file 1: table S7), on the middle part of LG4, were picked for haplotype analyses. FlexQTL implies this genomic region had more than one QTL within the same interval

Results discovered four SNP haplotypes associated with RD and FDP across the seven parents of which H1 was common (Table 3). Families of five parents (Y426–371, Y434–40, ‘Galaxy’, ‘Victor’, and TXW1490–1) were segregating in this region.

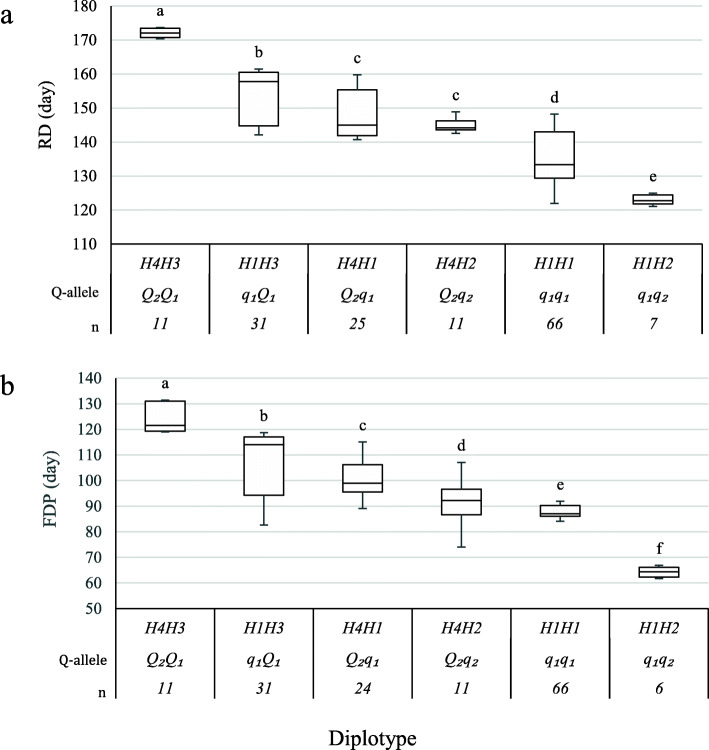

The diplotype analysis revealed the presence of four statistically distinct phenotypic classes (Fig. 3 a and b). H3 had a larger effect than H1 and H4 when comparing H4H3<>H4H1 and H1H3 <> H4H1, respectively. Likewise, H2 showed a smaller effect than H1 on both RD and FDP when comparing H1H1<>H1H2 and from H4H1<>H4H2 just in FDP not RD as their effects could not be differentiated (Fig. 3 a and b). Thus, the effect size of haplotypes can be ordered as H3 > H4 > H1 > H2 that is differentiated by Q1, Q2, q1, and q2, respectively. The major finding in this study was the presence of multiple QTL alleles of different effects for a single locus. That may explain why the Bayes Factor values and high intensities of most data sets of this study suggested the presence of two QTLs.

Fig. 3.

Diplotype effect of the most common haplotypes associated with ripening date (RD) a and fruit development period (FDP) b for the QTLs mapped on LG4. Means not connected by the same letter are significantly different (P < 0.05) within each linkage group. n = Diplotype sample size

Seven SNP markers were identified, each of which distinguished H3 and H4 from the other two haplotypes (Table 3). In this study, ‘Galaxy’, TX2B136, Y426–371, Y435–246, and Y434–40, were considered founders as their direct parents, and earlier generations do not exist or were not available for genotyping. Q1 (H3) was found in parent Y426–371, Y434–40, and ‘Galaxy’ (Table 3), while Q2 (H4) inherited from Fla3–2 through ‘TropicBeauty’. q1 (H1) was from Y434–40, Y435–246, ‘Galaxy’, TX2B136, F_Goldprince, and F_TXW1490–1. Y426–371 parent was the only source of q2 (H2). Thus, RD and FDP shared the same specific haplotypes and favorable SNP alleles associated with increasing/decreasing phenotypic values.

Discussion

In this study, the bloom date was moderate to highly heritable (0.44–0.82) as has been previously reported [15, 24–27] in a range of germplasm, indicating that expression of bloom date is not heavily influenced by environmental effects which were supported by G × E results. Narrow sense heritability was moderate to high for RD (0.59 to 0.83) as was found in previous studies [15, 18, 26, 46–48]. FDP also has an important additive genetic component as indicated by a high to very high (0.65 to 0.82) estimated narrow-sense heritability reported in this and previous studies [15, 24–27].

Our QTL for BD on LG1 was flanked by snp_1_46757382 and ss_128603, spanned the region from 43.1–45.6 Mb with PVE from ~ 17 to 54%. This QTL was previously described in different germplasm, by Romeu, et al. [30] in the ‘V6’ × ‘Granada’ progeny (low- medium chill) (41.2 Mb) at the end of LG1, PVE ~ 60%) and by Fan, et al. [29] using ‘Contender’ (high chill) and ‘Fla.92-2C’ (low chill) population (at 45.6 Mb, PVE ~ 40%).

The QTL at the middle region of LG4 for BD mapped between ss_413934 and ss_419614, in the interval between 12 and 13.6 Mb, and PVE ranged from 11 to 55%. This QTL overlaps with the BD QTL on LG4 (qFD4.2) at nearest markers ss_417840 and ss_440116 (13.1 to 16.0 Mb) reported by Hernández Mora, et al. [15].

Lastly, the QTL at the distal end of LG7 was flanked by ss778568 and snp_7_17628094, spanned from 15.5 to 17.2 Mb and explained ~ 11 to 18% of BD phenotypic variation. This finding agreed with Romeu, et al. [30] who found a QTL for BD on LG7 at the nearest marker ss_779224 (15.7 Mb), which was close to our QTL peaks (ss_780816 (16.3 Mb) and ss_779362 (15.7 Mb)). Moreover, this region overlapped with the QTL (15.4 to 19.4 Mb; PVE ~ 60%) reported by Fan, et al. [29].

The only one of the three QTLs was detected in CA11 is probably due to that this environment had a low number of phenotypic data (82 records). The G × E for BD in the studied populations may result from the response of the high-chill seedlings to the lack of chill hours that delayed the blooming period.

In summary, this study provides more evidence that three mapped QTLs for BD on LG1, 4, and 7 are major loci for controlling BD and were supported by other studies using low- and medium-chill germplasm and bi-parental family mapping. It was also supported by the polygenic nature of BD inheritance. Additional QTLs for BD were also reported on LG2 [15, 49], LG3 [17, 30], LG6 [15, 30, 50], and LG8 [15, 17]. Thus, further studies using more diverse germplasm will be important to continue to characterize additional QTLs and candidate genes to identify the genetic pathway regulating the BD in peach.

The examination of haplotype/diplotype effects uncovered the high prevalence of a few haplotypes, e.g., H8 (q-allele), H3 (Q-allele), and H7 (q-allele) on LG1, 4, and 7, respectively, reflecting the relatively narrow genetic base of peach germplasm. Also, the results revealed the presence of multiple Q-alleles of different effects for the QTL on LG1 (Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4) along with only one q-allele. In general, the small family sizes and consequently the low/lack representation of various compound diplotypes (e.g., 6 to 9 observations in some diplotypes of LG1) hindered the ability to make conclusions on the haplotype effects (H4 and H5) or the interplay among the three mapped QTLs for BD.

One QTL associated with RD and FDP was mapped at the middle part of LG4 (10.4–11.3 Mb) with PVE 46–75% and 40–71%, respectively. This specific genomic region was reported as associated with RD trait previously by Nuñez-Lillo, et al. [35] (~ 10.9 Mb), Romeu, et al. [30] (~ 10.7 Mb), Frett [18] (10.7–11.3 Mb), Eduardo et al. (2011; 2013) (~ 11.0–11.2 Mb) with candidate gene ppa008301m for maturity, and Hernández Mora, et al. [15] (~ 11.2–14.1 Mb). This held true using early-, mid-, and late-maturing populations. The co-localization between QTLs for RD and FDP was supported by the strong correlation (r = 0.87) (data not shown) between these traits in this study as well as previous work [6, 15].

Also, all data sets, except TX12, showed decisive evidence (BF ≥ 10) with high intensity for the presence of a second QTL on LG4. This could be explained by that TX12 had higher temperatures during the critical fruit development months (March and April) [51] compared to other sites. The higher temperatures accelerated RD and shortened FDP in this environment, which minimized the phenotypic variation as mentioned earlier (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Furthermore, the haplotype analysis of this chromosomal region revealed multiple predictive loci (ss_410398, ss_410794, and ss_412662) for decreasing and increasing for either RD or FDP. Likewise, examining the relative effects of haplotypes and estimated QTL genotypes revealed a series of QTL alleles of different effect at this locus that we coined Q1, Q2, q1, and q2. The use of multi-parent populations for finding multiple functional alleles of different effect was also reported for two acidity QTLs/genes in apple by Verma, et al. [52] and for the blush QTL in peach using the current germplasm by Rawandoozi, et al. [16]. In our germplasm, the RD QTL on LG4 co-localized with a QTL for soluble solids concentration (SSC) and blush reported by Rawandoozi, et al. [16]. These co-localizations had also been reported by other studies [15, 34, 53]. A pleiotropic effect of the RD has been reported on several quality traits [15, 34, 35, 39]. Co-factor analysis could be useful in future studies to account for one trait when analyzing another, e.g., accounting for RD for analyzing SSC or blush traits.

Overall, additional QTL mapping through pedigree-based analysis across a wider range of breeding germplasm is needed to identify and characterize additional QTLs to understand the whole genetic pathway controlling RD and FDP traits. Moreover, larger family sizes would ensure better representation of QTL genotype classes for estimating QTL effects and allow improved downstream analysis in case of multiple QTL alleles of different effects at a single locus and/or gene by gene interaction.

At the genomic region of the detected QTLs for these traits, candidate genes have been reported. For BD, the QTL interval (43,058,300 - 45,586,061 bp) of LG 1, the most promising candidate genes for the major QTL affecting blooming time and chilling requirement in LG1 were the Dormancy-associated MADS-box (DAM) genes within the evergrowing (evg) locus in peach, apricot, and almond [29, 54, 55].

Prupe.1G531600 (DAM5) and Prupe.1G531700 (DAM6) genes were identified as potential candidate genes of lateral bud endodormancy release in peach [29, 56, 57]. Prupe.1G531500 gene is described as MADS-box protein short vegetative phase (SVP) and it plays a role in controlling meristem development during the vegetative phase and flower development as well as in floral meristem determination [58]. Prupe.1G549600 and Prupe.1G548000 genes are described as agamous-like MADS-box proteins AGL11 and AGL12, respectively. AGL11 is a vital gene to control ovule identity and associated placental tissues in Arabidopsis [59]. While a MADS-box gene AGL12 regulates root development and flowering transition in Arabidopsis [60]. Prupe.1G554100 (AGL80) is also a member of the MADS-box family of genes. In Arabidopsis, AGL80 was found to be involved in female gametophyte development [61].

Likewise, many candidate genes have been reported within the interval (11,956,738-13,633,831 bp) of LG4. Prupe.4G208000 is described as a Forkhead-associated (FHA) domain-containing protein (DDL) that plays an important role in plant growth and development [62]. Prupe.4G197000 gene was proposed to link to auxin synthesis and response which is known to be involved in fruit set and ripening [63]. Prupe.4G202200, Fertilization Independent Endosperm (FIE) polycomb group protein, in Arabidopsis thaliana FIE regulates endosperm and embryo development and suppresses flowering during embryo and seedling development [64]. Prupe.4G207300 (uclacyanin) is associated with pollen grain development in rice [65]. Prupe.4G205500 (early nodulin-like protein 1) gene is reported to be engaged in determining the reproductive potential in Arabidopsis [66]. In the QTL region (15,513,277-17,226,623 bp) of LG7, Prupe.7G130900, CURLY LEAF (CLF) gene, is associated with the repression of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene and other flowering-time genes during the vegetative growth of the plant [67]. Prupe.7G153400 gene is described as a ATP-dependent DNA helicase (DDM1), the importance of this gene was previously reported for DNA methylation in genes and transposable elements [68]. Prupe.7G133100 (Zeaxanthin epoxidase) gene has been identified to play an important role in resistance to stresses, seed development, and dormancy in Arabidopsis [69].

Within the RD/FDP locus on LG4 (10,582,092 to 11,298,736), a list of candidate genes has been previously reported in this region. NAC072 (Prupe.4G816800) is the candidate gene for controlling the ripening date in peach [39]. Also, there are three other genes proposed to be involved in the determination of RD/FDP in peach. Prupe.4G79900 gene is needed for normal embryo development in Arabidopsis and maize [70, 71]. Prupe.4G179800 gene is described as Early nodulin- like protein 1 and PtNIP1in Arabidopsis and loblolly pine, respectively [72]. It is expressed in immature zygotic and somatic embryos of developing seeds. Prupe.4G179200 gene with functional annotation Purine permease 10 in Arabidopsis and OsPUP7 in rice [73], and showed a flowering delay in rice. Finally, Prupe.4G185800 [74] and Prupe.4G187100 [75] genes that were reported to be associated with the regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in peach. Hence, these results confirming the pleiotropic effect of the RD on several quality traits, including blush that was previously reported [15, 16, 34, 35, 39].

Conclusions

The pedigree-based analysis was successfully used as a statistical method for discovering and validating QTLs. Four QTLs associated with three important phenological traits were validated using low- medium-chill peach/nectarine germplasm. Two minor QTLs were also identified. This approach increases the genetic background explored, improves statistical power, and allows the simultaneous detection and validation of QTLs.

QTLs for BD on LG1, 4, and 7 were verified, and the SNP haplotypes associated with increasing or decreasing BD were identified. A single QTL with multiple QTL alleles of different effects was detected on the central part of LG4 for both RD and FDP. Our findings would help breeding programs make crossing decisions to pick the combination of parents that have SNP haplotypes associated with lowering BD to produce progeny with better adaptation to subtropical environments like Texas or increasing BD to ensure better adaptation to temperate environments, whereas the results of RD and FDP will facilitate better targeting for specific ripening periods. Ultimately, the SNP haplotypes associated with these QTLs could be converted into easy-to-use high throughput markers (e.g., Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR), Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP), and Sequence Characterized Amplified Region (SCAR) markers) to routinely use in MAB. In general, this approach would save time and resources, particularly for fruit breeders since perennial wood species have long juvenility periods, and large populations are expensive to maintain in the field.

Methods

Plant materials

Briefly, we included in this study 143 seedlings from seven related F1 families derived from seven parents descending from 12 founders. The parents are all cultivated germplasm that has been developed by the Stone Fruit Breeding programs at Texas A&M University in College Station, TX and the USDA Stone Fruit Breeding program in Parlier, CA (36° 36′ 25.19″ N; − 119° 31′ 22.19″ W). TX2B136, ‘Victor’, TXW1490_1 from the Texas germplasm are mainly derived from ‘Tropic Beauty’ and related selections of Florida peach germplasm and ‘Goldprince’ and ‘Springbrite’ developed in the USDA Stone Fruit Breeding program in Byron, GA. On the other hand, ‘Galaxy’, Y435–246, Y424–40, and Y426–371 were developed by the USDA Stone Fruit Breeding program from ‘Armking’ and germplasm from Rutgers University (New Brunswick, NJ), the University of Florida (Gainesville, FL), and Georgia USDA Stone Fruit Breeding program (Byron, GA). Seedlings and parental genotypes were grown in College Station, TX (30°37′41.60″N, 96°22′27.38″W), and Fowler, CA (36°38′21.37″N, 119°42′20.51″W). Full details on plant materials and plot establishment and design can be found in Rawandoozi, et al. [16].

Phenotypic evaluations

Phenotypic data were taken at both locations across 2 years (2011–2012 in CA, and 2012–2013 in TX) on individual trees for three phenological traits, bloom date (BD), ripening date (RD), and fruit development period (FDP). The date of first (10% blossoms open) and full bloom (60 to 80% of the blossoms open) were visually assessed in the field and recorded for each tree. Ripening date was determined when 20% of fruits are pickable by visually inspecting the presence of a few soft fruits in the field for maturity two times per week. Both full bloom and ripening dates were converted to Julian days (0–365). FDA is difference in days between BD and RD.

Heritability and G × E

Variance components for the studied traits were estimated using a linear mixed model with the residual maximum likelihood (REML). Results from REML were used to estimate the broad-sense heritability across the environments, as explained by Rawandoozi, et al. [16]. The R package GGEBiplots version 0.1.1 was used to estimate the variations due to genotypes and G × E. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were also estimated among phenotypic traits within and across the environments using R software version 4.0.3.

Genotyping and linkage map

Plant samples were genotyped using the IPSC 9 K SNP Array for Peach [11], and SNP data were curated following the workflow described by Vanderzande, et al. [76]. After filtration, a total of 1487 informative SNPs were distributed over eight chromosomes using a conversion factor in which every 1 Mb corresponded to 4 cM [76].

QTL mapping

FlexQTL software (version 0.1.0.42) with an additive genetic model conducted by Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation was used for QTL mapping. The analysis was run at least three times on each data set. Different prior and maximum QTL numbers were used in each run to reach effective chain size (ECS) ≥ 100 for the mean, variance of the error, number of QTLs, and QTL variance, as recommended to draw reliable and accurate conclusions [13, 77]. MCMC length ranged from 100,000 to 3600,000 iterations to store one thousand samples with a thinning between 100 and 3600. Convergence was evaluated visually via trace and intensity plots [13]. Twice the natural logarithm of Bayes Factors [2ln(BF)] obtained from FlexQTL software used as evidence for presence and number of QTLs [78]. The 2ln(BF) value greater than 2, 5, or 10 indicate positive, strong, and decisive evidence, respectively. In this study, loci were considered if QTL had 2lnBF ≥ 5 or that 2 ≤ 2lnBF < 5 for at least two data sets, the QTLs with overlapping intervals of at least 2 cM on the same linkage group, and explained at least 10% of the phenotypic variation.

The additive (, phenotypic , and residual variances were obtained from FlexQTL output to estimate the narrow-sense heritability (h2), and the proportion of phenotypic variance explained (PVE) as follows:

The QTL nomenclature in this study described by Rawandoozi, et al. [16] is a modification of that of Fan et al. [29].

Haplotypes analysis

SNPs within the significant QTL interval were considered for haplotype analysis using the FlexQTL software and PediHaplotyper package of R [19]. Haplotype effects were determined from combinations of diplotypes by comparing the effects of the H1|H2 and H1|H3 diplotypes. The nonparametric multiple comparison Steele–Dwass test (P < 0.05) was used to assess the significance of differences using JMP Pro Version 13.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 2016) as described by Rawandoozi, et al. [16].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1; Supplemental Tables S1-S7

Additional file 2: Supplemental Figure S1-S5.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Nahla Bassil and her lab team for conducting DNA extraction, Dr. David Ramming of the USDA for supplying germplasm used in this study, the Burchell Nursery, Inc., and Fruit Dynamics, Inc. for facilitating the development and maintenance of the research plot and assistance with the fruit evaluations at Fowler, CA, to Ricky Garcia and Natalie Anderson and the Department of Horticultural Sciences, Texas A&M University for their support in the field and lab, to Dr. Sujeet Verma (University of Florida) for his advice during data analysis.

Abbreviations

- BF

Bayes factor

- CG

Candidate gene

- cM

Centimorgan

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ECS

Effective chain size

- F1

First filial generation

- FS

Full-sib

- h2

Narrow-sense heritability

- H2

Broad-sense heritability

- LG

Linkage group

- Mb

Megabase pair

- MCMC

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- PVE

Phenotypic variance explained

- QTL

Quantitative trait loci

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- BD

Bloom date

- RD

Ripening date

- FDP

Fruit development period

- MAB

Marker-assisted breeding

Authors’ contributions

D.H.B. conceived this study, Z.R. carried out the analysis, T.H., D.H.B., and S.C. provided phenotypic data, K.G., C.L., L.C. developed the SNP genotyping and produced the linkage map, and E.V.W provided support for performing the pedigree-based analysis and interpretation of the results. Z.R., D.H.B., and E.V.W drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final and reviewed manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI) project, “RosBREED: Enabling marker-assisted breeding in Rosaceae” (2009–51181-05808). The project supported phenotyping, genotyping, map construction, annual meetings for training in the use of FlexQTL software on the national project level, and travel to annual meetings.

Availability of data and materials

The genotypic and phenotypic datasets of seven full-sib peach families used in this study can be found in the Dryad Repository, 10.5061/dryad.tmpg4f4vp (https://datadryad.org/stash/share/oWBiP7isZFdQbY8zS0nTubqrhrT0RntovILSNJp9Xxc).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zena J. Rawandoozi, Email: zjmansur@tamu.edu

Timothy P. Hartmann, Email: t-hartmann@tamu.edu

Silvia Carpenedo, Email: carpenedo.s@hotmail.com.

Ksenija Gasic, Email: kgasic@clemson.edu.

Cassia da Silva Linge, Email: cassia.linge@gmail.com.

Lichun Cai, Email: lichun.cai725@gmail.com.

Eric Van de Weg, Email: eric.vandeweg@wur.nl.

David H. Byrne, Email: dbyrne@tamu.edu

References

- 1.FAOSTAT. The Statistics Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC. Accessed 20 Jan 2020

- 2.Peace CP, Luby JJ, van de Weg WE, Bink MCAM, Iezzoni AF. A strategy for developing representative germplasm sets for systematic QTL validation, demonstrated for apple, peach, and sweet cherry. Tree Genet Genomes. 2014;10(6):1679–1694. doi: 10.1007/s11295-014-0788-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bliss FA. Marker-assisted breeding in horticultural crops. Acta Hort. 2010;859:339–350. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2010.859.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testolin R, Cipriani G. Molecular markers for germplasm identification and characterization. Acta Hort. 2010;859:59–72. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2010.859.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeballos J. Identification of genomic region related to fruit quality traits in peach. Zaragoza: Universidad de Lleida; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etienne C, Rothan C, Moing A, Plomion C, Bodénès C, Svanella-Dumas L, et al. Candidate genes and QTLs for sugar and organic acid content in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105(1):145–159. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0841-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quilot B, Wu BH, Kervella J, Génard M, Foulongne M, Moreau K. QTL analysis of quality traits in an advanced backcross between Prunus persica cultivars and the wild relative species P. davidiana. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(4):884–897. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1703-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantín CM, Crisosto CH, Ogundiwin EA, Gradziel T, Torrents J, Moreno MA, et al. Chilling injury susceptibility in an intra-specific peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] progeny. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2010;58(2):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eduardo I, Chietera G, Pirona R, Pacheco I, Troggio M, Banchi E, et al. Genetic dissection of aroma volatile compounds from the essential oil of peach fruit: QTL analysis and identification of candidate genes using dense SNP maps. Tree Genet Genomes. 2013;9(1):189–204. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0546-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arús P, Verde I, Sosinski B, Zhebentyayeva T, Abbott AG. The peach genome. Tree Genet Genomes. 2012;8(3):531–547. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0493-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verde I, Bassil N, Scalabrin S, Gilmore B, Lawley CT, Gasic K, et al. Development and Evaluation of a 9K SNP Array for Peach by Internationally Coordinated SNP Detection and Validation in Breeding Germplasm. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bink MCAM, Totir LR, Braak CJF, Winkler CR, Boer MP, Smith OS. QTL linkage analysis of connected populations using ancestral marker and pedigree information. Theor Appl Genet. 2012;124(6):1097–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bink MCAM, Jansen J, Madduri M, Voorrips RE, Durel CE, Kouassi AB, et al. Bayesian QTL analyses using pedigreed families of an outcrossing species, with application to fruit firmness in apple. Theor Appl Genet. 2014;127(5):1073–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00122-014-2281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frett TJ, Reighard GL, Okie WR, Gasic K. Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with blush in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] Tree Genet Genomes. 2014;10(2):367–381. doi: 10.1007/s11295-013-0692-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernández Mora JR, Micheletti D, Bink MCAM, Van de Weg E, Cantín C, Nazzicari N, et al. Integrated QTL detection for key breeding traits in multiple peach progenies. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:404. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3783-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rawandoozi ZJ, Hartmann TP, Carpenedo S, Gasic K, da Silva Linge C, Cai L, et al. Identification and characterization of QTLs for fruit quality traits in peach through a multi-family approach. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):522. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-06927-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fresnedo-Ramírez J, Bink MCAM, van de Weg E, Famula TR, Crisosto CH, Frett TJ, et al. QTL mapping of pomological traits in peach and related species breeding germplasm. Mol Breed. 2015;35:166. doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0357-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frett TJ. Genetic determinism of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni (Xap) resistance, fruit quality, and phenological traits in peach and incorporation of marker-assisted selection (MAS) in the University of Arkansas peach and nectarine breeding program. Diss. Fayetteville: Univ. Ark; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voorrips RE, Bink MCAM, Kruisselbrink JW, Koehorst-van Putten HJJ, van de Weg WE. PediHaplotyper: software for consistent assignment of marker haplotypes in pedigrees. Mol Breeding. 2016;36:119. doi: 10.1007/s11032-016-0539-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrne DH, Sherman WB, Bacon TA. Stone fruit genetic pool and its exploitation for growing under warm winter conditions. In: Erez A, editor. Temperate Fruit Crops in Warm Climates. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2000. pp. 157–230. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz D, Campoy JA, Egea J. Chilling and heat requirements of apricot cultivars for flowering. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;61(3):254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alburquerque N, Garcia-Montiel F, Carrillo A, Burgos L. Chilling and heat requirements of sweet cherry cultivars and the relationship between altitude and the probability of satisfying the chill requirements. Environ Exp Bot. 2008;64(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monet R, Bastard Y. Estimation du coefficient de régression enfant/parent de quelques caractères du pêcher dans le cas de familles issues d'autofécondations. Agronomie. 1982;2(4):347–358. doi: 10.1051/agro:19820406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mowrey BD, Sherman WB. Flower bud set and relationship to vigor in 18-month peach seedlings. Proc Fla State Hort Soc. 1986;99:209–210. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansche PE. Heritability of spring bloom and fall leaf abscission dates in Prunus persica. HortScience. 1990;25(12):1639–1641. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.25.12.1639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Souza VAB, Byrne DH, Taylor JF. Heritability, genetic and phenotypic correlations, and predicted selection response of quantitative traits in peach: I. An analysis of several reproductive traits. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1998;123(4):598–603. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.123.4.598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Souza VAB, Byrne DH, Taylor JF. Predicted breeding values for nine plant and fruit characteristics of 28 peach genotypes. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 2000;125(4):460–465. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.125.4.460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verde I, Quarta R, Cedrola C, Dettori MT. QTL analysis of agronomic traits in a BC1 peach population. Acta Hort. 2002;592:291–297. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2002.592.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan S, Bielenberg DG, Zhebentyayeva TN, Reighard GL, Okie WR, Holland D, et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci associated with chilling requirement, heat requirement and bloom date in peach (Prunus persica) New Phytologist. 2010;185(4):917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romeu JF, Monforte AJ, Sánchez G, Granell A, García-Brunton J, Badenes ML, et al. Quantitative trait loci affecting reproductive phenology in peach. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(52) 10.1186/1471-2229-14-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dirlewanger E, Quero-García J, Le Dantec L, Lambert P, Ruiz D, Dondini L, et al. Comparison of the genetic determinism of two key phenological traits, flowering and maturity dates, in three Prunus species: Peach, apricot and sweet cherry. Heredity. 2012;109(5):280–292. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2012.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansche PE. Heritability of fruit quality traits in peach and nectarine breeding stocks dwarfed by the dw gene. HortScience. 1986;21(5):1193–1195. [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Souza VAB, Byrne DH, Taylor JF. Heritability, genetic and phenotypic correlations, and predicted selection response of quantitative traits in peach: II. An analysis of several fruit traits. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 1998;123(4):604–601. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.123.4.604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eduardo I, Pacheco I, Chietera G, Bassi D, Pozzi C, Vecchietti A, et al. QTL analysis of fruit quality traits in two peach intraspecific populations and importance of maturity date pleiotropic effect. Tree Genet Genomes. 2011;7(2):323–335. doi: 10.1007/s11295-010-0334-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuñez-Lillo G, Cifuentes-Esquivel A, Troggio M, Micheletti D, Infante R, Campos-Vargas R, et al. Identification of candidate genes associated with mealiness and maturity date in peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch] using QTL analysis and deep sequencing. Tree Genet Genomes. 2015;11(86) 10.1007/s11295-015-0911-9.

- 36.Sánchez‐Pérez R, Howad W, Dicenta F, Arús P, Martínez‐Gómez P. Mapping major genes and quantitative trait loci controlling agronomic traits in almond. Plant Breed. 2007;126(3):310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01329.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blake MA. The J.H. Hale as a parent in peach crosses. Proc Amer Soc. Hort Sci. 1932;29:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vileila-Morales EA, Sherman WB, Wilcox CJ, Andrews CP. Inheritance of short fruit development period in peach. J Am Soc Hort Sci. 1981;106:399–401. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirona R, Eduardo I, Pacheco I, Da Silva Linge C, Miculan M, Verde I, et al. Fine mapping and identification of a candidate gene for a major locus controlling maturity date in peach. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13(1):166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byrne DH. Trends in stone fruit cultivar development. HortTechnol. 2005;15(3):494–500. doi: 10.21273/HORTTECH.15.3.0494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edge-Garza DA, Luby JJ, Peace C. Decision support for cost-efficient and logistically feasible marker-assisted seedling selection in fruit breeding. Mol Breed. 2015;35(12):223. doi: 10.1007/s11032-015-0409-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ru S, Main D, Evans K, Peace C. Current applications, challenges, and perspectives of marker-assisted seedling selection in Rosaceae tree fruit breeding. Tree Genet Genomes. 2015;11 10.1007/s11295-015-0834-5.

- 43.Weather Underground. Average high/low temperatures for KCLL. Seasonal averages http://www.wunderground.com/NORMS/DisplayNORMS.asp?AirportCode=KCLL&SafeCityName=College_Station&StateCode=TX&Units=none&IATA=CLL. Accessed 8 July 2018.

- 44.Koebner RMD. Marker Assisted Selection in the Cereals: The Dream and the Reality. In: Gupta PK, Varshney RK, editors. Cereal Genomics. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2005. pp. 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voorrips RE. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered. 2002;93(1):77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daines RH, Hough LF. Artificial inoculation of peach seedlings with Xanthomonas pruni. Phytopathol. 1951;41(1):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey CH, Hough LF. A hypothesis for the inheritance of season of ripening in progenies from certain early ripening peach varieties and selections. Proc Amer Soc. Hort Sci. 1959;73:125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu M, Ma R, Tang X. Inheritance of ripening season in F1 hybrids of peach. Jiangsu J Agr Sci. 1997;13:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dirlewanger E, Moing A, Rothan C, Svanella L, Pronier V, Guye A, et al. Mapping QTLs controlling fruit quality in peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch) Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(1):18–31. doi: 10.1007/s001220051035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joobeur T, Viruel MA, de Vicente MC, Jáuregui B, Ballester J, Dettori MT, et al. Construction of a saturated linkage map for Prunus using an almond×peach F2 progeny. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97(7):1034–1041. doi: 10.1007/s001220050988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weather Underground. Weather History for Fresno, CA. http://www.wunderground.com/history/airport/KFAT/2012/8/10/MonthlyHistory.html.Accessed 10 Sept 2018.

- 52.Verma S, Evans K, Guan Y, Luby JJ, Rosyara UR, Howard NP, et al. Two large-effect QTLs, Ma and Ma3, determine genetic potential for acidity in apple fruit: breeding insights from a multi-family study. Tree Genet Genomes. 2019;15:18. doi: 10.1007/s11295-019-1324-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hernández Mora JR, Micheletti D, Bink MCAM, Van de Weg WE, Bassi D, Nazzicari N, et al. Discovering peach QTLs with multiple progeny analysis. Acta Hort. 1172;2017:405–410. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olukolu BA, Trainin T, Fan S, Kole C, Bielenberg DG, Reighard GL, et al. Genetic linkage mapping for molecular dissection of chilling requirement and budbreak in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) Genome. 2009;52(10):819–828. doi: 10.1139/G09-050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sánchez-Pérez R, Dicenta F, Martínez-Gómez P. Inheritance of chilling and heat requirements for flowering in almond and QTL analysis. Tree Genet Genomes. 2012;8(2):379–389. doi: 10.1007/s11295-011-0448-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamane H, Ooka T, Jotatsu H, Hosaka Y, Sasaki R, Tao R. Expressional regulation of PpDAM5 and PpDAM6, peach (Prunus persica) dormancy-associated MADS-box genes, by low temperature and dormancy-breaking reagent treatment. J Expt Bot. 2011;62(10):3481–3488. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiménez S, Reighard GL, Bielenberg DG. Gene expression of DAM5 and DAM6 is suppressed by chilling temperatures and inversely correlated with bud break rate. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;73(1):157–167. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gregis V, Andrés F, Sessa A, Guerra RF, Simonini S, Mateos JL, et al. Identification of pathways directly regulated by SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE during vegetative and reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2013;14(6):R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rounsley SD, Ditta GS, Yanofsky MF. Diverse roles for MADS box genes in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell. 1995;7(8):1259–1269. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tapia-López R, García-Ponce B, Dubrovsky JG, Garay-Arroyo A, Pérez-Ruíz RV, Kim S-H, et al. An AGAMOUS-related MADS-box gene, XAL1 (AGL12), regulates root meristem cell proliferation and flowering transition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(3):1182–1192. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smaczniak C, Immink RGH, Angenent GC, Kaufmann K. Developmental and evolutionary diversity of plant MADS-domain factors: insights from recent studies. Dev. 2012;139(17):3081–3098. doi: 10.1242/dev.074674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morris ER, Chevalier D, Walker JCDAWDLE. a forkhead-associated domain gene, regulates multiple aspects of plant development. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(3):932–941. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.076893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seymour G, Poole M, Manning K, King GJ. Genetics and epigenetics of fruit development and ripening. Current Opinion Plant Biol. 2008;11(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz A, Oliva M, Mosquna A, Hakim O, Ohad N. FIE and CURLY LEAF polycomb proteins interact in the regulation of homeobox gene expression during sporophyte development. Plant J. 2004;37(5):707–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y-C, He R-R, Lian J-P, Zhou Y-F, Zhang F, Li Q-F, et al. OsmiR528 regulates rice-pollen intine formation by targeting an uclacyanin to influence flavonoid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(1):727–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810968117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khan JA, Wang Q, Sjölund RD, Schulz A, Thompson GA. An early nodulin-like protein accumulates in the sieve element plasma membrane of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(4):1576–1589. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim G-T, Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. The CURLY LEAF gene controls both division and elongation of cells during the expansion of the leaf blade in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1998;206(2):175–183. doi: 10.1007/s004250050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zemach A, Kim MY, Hsieh P-H, Coleman-Derr D, Eshed-Williams L, Thao K, et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell. 2013;153:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park H-Y, Seok H-Y, Park B-K, Kim S-H, Goh C-H, Lee B-H, et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ZEP enhances tolerance to osmotic stress. BioChem Biophysical Res Commun. 2008;375(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tzafrir I, Pena-Muralla R, Dickerman A, Berg M, Rogers R, Hutchens S, et al. Identification of genes required for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135(3):1206–1220. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shen Y, Li C, McCarty DR, Meeley R, Tan B-C. Embryo defective12 encodes the plastid initiation factor 3 and is essential for embryogenesis in maize. Plant J. 2013;74(5):792–804. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ciavatta VT, Morillon R, Pullman GS, Chrispeels MJ, Cairney J. An aquaglyceroporin is abundantly expressed early in the development of the suspensor and the embryo proper of loblolly pine. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(4):1556–1567. doi: 10.1104/pp.010793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qi Z, Xiong L. Characterization of a purine permease family gene OsPUP7 involved in growth and development control in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2013;55(11):1119–1135. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jung S, Ficklin SP, Lee T, Cheng CH, Blenda A, Zheng P et al. The genome database for Rosaceae (GDR): year 10 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D1237-D1244. 10.1093/nar/gkt1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Zhou H, Lin-Wang K, Wang H, Gu C, Dare AP, Espley RV, et al. Molecular genetics of blood-fleshed peach reveals activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by NAC transcription factors. Plant J. 2015;82(1):105–121. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vanderzande S, Howard NP, Cai L, Da Silva Linge C, Antanaviciute L, Bink MCAM, et al. High-quality, genome-wide SNP genotypic data for pedigreed germplasm of the diploid outbreeding species apple, peach, and sweet cherry through a common workflow. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0210928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sorensen D, Gianola D. Likelihood, Bayesian, and MCMC methods in quantitative genetics. New York: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes Factors. J Amer Stat Assn. 1995;90(430):773–795. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1; Supplemental Tables S1-S7

Additional file 2: Supplemental Figure S1-S5.

Data Availability Statement

The genotypic and phenotypic datasets of seven full-sib peach families used in this study can be found in the Dryad Repository, 10.5061/dryad.tmpg4f4vp (https://datadryad.org/stash/share/oWBiP7isZFdQbY8zS0nTubqrhrT0RntovILSNJp9Xxc).