Abstract

Ticks are ectoparasitic arthropods that necessarily feed on the blood of their vertebrate hosts. The success of blood acquisition depends on the pharmacological properties of tick saliva, which is injected into the host during tick feeding. Saliva is also used as a vehicle by several types of pathogens to be transmitted to the host, making ticks versatile vectors of several diseases for humans and other animals. When a tick feeds on an infected host, the pathogen reaches the gut of the tick and must migrate to its salivary glands via hemolymph to be successfully transmitted to a subsequent host during the next stage of feeding. In addition, some pathogens can colonize the ovaries of the tick and be transovarially transmitted to progeny. The tick immune system, as well as the immune system of other invertebrates, is more rudimentary than the immune system of vertebrates, presenting only innate immune responses. Although simpler, the large number of tick species evidences the efficiency of their immune system. The factors of their immune system act in each tick organ that interacts with pathogens; therefore, these factors are potential targets for the development of new strategies for the control of ticks and tick-borne diseases. The objective of this review is to present the prevailing knowledge on the tick immune system and to discuss the challenges of studying tick immunity, especially regarding the gaps and interconnections. To this end, we use a comparative approach of the tick immune system with the immune system of other invertebrates, focusing on various components of humoral and cellular immunity, such as signaling pathways, antimicrobial peptides, redox metabolism, complement-like molecules and regulated cell death. In addition, the role of tick microbiota in vector competence is also discussed.

Keywords: cell-mediated immunity, immune signaling pathway, immune system, microbiota, tick-borne pathogen

Introduction

Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) are ectoparasitic arthropods that obligatorily feed on the blood of a diverse list of vertebrate hosts, including mammals, birds, reptiles, and even amphibians. More than 950 tick species have been described to date, which, according to morphological and physiological characteristics, are divided into two main families, Ixodidae (hard ticks), comprising more than 75% of tick species, and Argasidae (soft ticks); a third family, known as Nuttalliellidae, is monospecific (1, 2). As a result of blood spoliation [a single ixodid adult female can ingest more than ~1 mL of blood (3)], the host can suffer from anemia, which negatively impacts the productivity of livestock and causes a huge economic burden worldwide. For example, the estimated annual losses due to reductions in weight gain and milk production caused by the cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus are approximately 3.24 billion dollars in Brazil alone (4).

In addition to ingesting blood, ticks also secrete saliva into the host during feeding. Tick saliva, produced by their salivary glands, returns excess water and ions to the host, thereby concentrating the blood meal (5). Tick saliva contains an arsenal of bioactive molecules that modulate host hemostasis and immune reactions, thus enabling blood acquisition (6, 7). The antihemostatic and immunomodulatory properties of saliva can also facilitate the infection of pathogens that use saliva as a vehicle to be transmitted to the host during tick blood feeding (6, 8). Indeed, ticks are versatile vectors of viruses, bacteria, protozoans and nematodes, which cause life-threatening diseases to humans as well as to other animals, including livestock, pets, and wildlife (9). Among human diseases, we highlight Lyme disease, the most common tick-borne zoonosis, which is caused by spirochetes from the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex. After transmission by the bite of an infected tick, the typical clinical sign of Lyme disease is erythema migrans, but infection can spread and affect joints, heart, and the nervous system (10).

The first organ that a pathogen acquired within the blood meal interacts with is the tick gut (Figure 1). Then, the pathogen must colonize the gut epithelial cells and/or cross the gut epithelium to enter the hemocoel, an open body cavity filled with hemolymph, the fluid that irrigates all the tissues and organs in the tick. The pathogen must then reach the salivary glands. In each of these organs, the pathogen must counteract tick immune factors to be successfully transmitted through saliva to the vertebrate host in a subsequent blood-feeding (11). Some pathogens also have the ability to invade tick ovaries and can therefore be transovarially transmitted to progeny (Figure 1). Thus, elucidation of the immune factors involved in the interactions between ticks and tick-borne pathogens (TBPs) in each of these steps is essential to understand the biology of tick-transmitted diseases and may help to identify targets for the development of new strategies to block pathogen transmission. In this review, we present an update on humoral and cellular tick immunity components (Figure 1), including signaling pathways, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), redox metabolism, complement-like proteins, and regulated cell death. Using a comparative approach with the immune system of other invertebrates, we highlight the challenges of studying tick immunity, the gaps, such as prophenoloxidase (PPO) and coagulation cascades, and the interconnections, such as immune system signaling pathway crosstalk. In addition, the role of tick microbiota in vector competence is also discussed.

Figure 1.

Main interactions among tick immune system components, microbiota, and pathogens. Pathogens ingested within the blood meal initially reach the tick gut, where they interact with components of the gut microbiota and with cytotoxic molecules, such as AMPs (hemocidins and endogenous AMPs) and possibly with factors of redox metabolism, despite not being fully comprised. Pathogens must colonize and/or cross the gut epithelium to reach the hemocoel, which is filled with hemolymph. In hemolymph, complement-like molecules attach to pathogens that can be engulfed or trapped by hemocyte-mediated processes named phagocytosis and nodulation, respectively. Invaders can also be killed by several types of effector molecules, including AMPs, complement-like molecules, and factors of redox metabolism. The tick salivary glands return excess water and ions from the blood meal to the host through saliva, which also contains antihemostatic and immunomodulatory molecules. Pathogens use tick saliva as a vehicle to be transmitted to the host, in which infection can be facilitated by saliva properties. Some pathogens can also colonize the tick ovaries and are transmitted to progeny. In the tick salivary glands and ovaries, as in the gut, pathogens must deal with the members of resident microbiota as well as tick immune reactions. Additional studies are required to elucidate the molecules responsible for hemolymph clotting and melanization in ticks.

A Brief History of Studies on the Immune System of Arthropods

The first records of studies on arthropod disease date to the 19th century, when Louis Pasteur investigated the cause of brown dots on the cuticle of larvae of Bombyx mori that predestined larvae to death and affected silk production in France (12). In the 1980s, the isolation of several immune factors from the hemolymph of arthropods that have a large volume of hemolymph, such as larvae of dipteran and lepidopteran insects, horseshoe crabs and crayfish, was achieved. Indeed, the first animal AMP to be characterized was cecropin, isolated from the hemolymph of the moth Hyalophora cecropia (13). After that, AMPs were identified as important effectors of mammalian immunity (14, 15). In addition to AMPs, components of the PPO cascade from the hemolymph of H. cecropia (16), B. mori (17), and the crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus (18) were also elucidated. Some years later, the components of the coagulation cascade, another important arthropod immune reaction, were characterized in P. leniusculus (19) and horseshoe crabs (20).

In the 1990s, relevant studies on the immune pathways that regulate AMP production were conducted using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (hereafter referred to as Drosophila) as a model (21–24). Among them, we highlight the identification of a kappa B (κB)-binding region in the promotor region of certain insect AMP genes (25) and the identification of Toll receptors, posteriorly identified to be homologous to interleukin-1 receptor of mammals (26). Some years later, with the improvement of molecular techniques and funding by major support agencies, such as the MacArthur Foundation, the World Health Organization, and the National Institutes of Health (USA), studies on the arthropod immune system were redirected to vectors of human diseases, principally mosquitoes (27). In this period, Sanger-based technology was largely used to elucidate genomes and generate datasets of expressed sequence tags (ESTs). After the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, additional information on arthropod genomes and transcriptomes was added to public databases (28). Indeed, currently, more than 40 arthropod genomes are available in the VectorBase database (https://www.vectorbase.org/organisms).

Knowledge of vector genomes and ESTs allowed in silico comparisons of immune factors among species [for example, see (29–33)]. Moreover, studies with diverse approaches, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics analyses, to assess the arthropod response to different microbial stimuli were significantly expanded in the postgenomic era (28). The development and application of RNA interference (RNAi) and CRISPR-Cas9 technologies to arthropods [(34, 35), respectively] were also important to determine the role played by immune factors in the interaction between vectors and vector-borne pathogens.

Despite the importance of ticks as disease vectors, studies on their genomes and the molecular factors involved in their interactions with pathogens are scarce compared to studies on other arthropod vectors. The large size of tick genomes and the high contents of repetitive regions make genome assembly difficult. Indeed, the size of tick genomes is approximately 1.3 Gbp in argasids and 2.6 Gbp in ixodids (36). However, the genome of the cattle tick R. microplus is even larger and has been estimated to be approximately 7.1 Gpb, which is more than twice the size of the human genome (37). In addition, approximately 70% of the tick genome includes repetitive regions (37, 38). For this reason, until very recently, only the genome of the tick Ixodes scapularis had been annotated (38). Additional genomes were recently assembled by the use of NGS (37, 39). The scarcity of studies on the molecular factors involved in ticks and TBPs is in part due to the need for sophisticated structures to raise vertebrate animals to feed ticks, which is laborious and involves ethical concerns. In the last few years, artificial feeding systems have been successfully used to maintain laboratory tick colonies; however, an animal blood source is still required (40). Finally, the development of continuous cell lines derived from tick embryos, despite representing a mixture of different cell types, has also contributed considerably to studies on tick biology and their interactions with TBPs (41).

Tick Immune Signaling Pathways

Blood feeding represents a challenge for hematophagous arthropods due to the large diversity of pathogens to which these animals are exposed. In contrast to other arthropods, hard ticks are strictly hematophagous, feeding on the blood of their host for several days. In addition, some species feed on a different host in each developmental stage (larvae, nymphs, and adults), thereby increasing the chance of either acquiring or transmitting pathogens. Therefore, ticks are important vectors of a large list of disease-causing pathogens (42). In addition to host pathogens, ticks are in close contact with the microbiota of the host skin, which may also be acquired within the blood meal (43). Ticks are also exposed to microorganisms in the environment during the nonparasitic phases of their life cycle. Hence, the immune system of ticks must be activated continuously to protect them from harmful infections.

Most of our knowledge on arthropod immune responses has come from studies on dipteran insects, especially Drosophila and the mosquitoes Aedes spp. and Anopheles spp. In Drosophila, invading microorganisms are mainly recognized by the Toll, immune deficiency (IMD), Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK), Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) and/or RNAi pathways (44). Nonetheless, the hypothesis that the level of conservation of arthropod immune responses might be high has been rejected by several studies on ticks, mites, lice, hemipterans, and others, and it is now recognized that the immune system displays remarkable diversification across the Arthropoda phylum (30). Tick immunity is, however, still greatly neglected and unexplored (45). Hence, we review the prevailing knowledge on tick immune signaling pathways alongside the connections between them and other equally important factors, such as AMPs, redox metabolism, complement-like proteins, and regulated cell death.

Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Signaling Pathways: Molecular Regulators for Pathogen Recognition

The Unexplored Toll Pathway

The Toll signaling pathway is well studied in Drosophila, in which it is preferentially activated in the presence of bacterial [by recognition of lysine-type peptidoglycan (PGN) from the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria) and fungal (by recognition of (1,3)-glucan polymers of D-glucose from the cell wall] pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (44, 46). In silico and genomic analyses have shown that ticks encode most Toll pathway components (31, 33, 38, 47) (Figure 2A), including the NF-κB Dorsal, indicating that conserved mechanisms of Toll pathway activation may exist. Indeed, the NF-κB transcription factor dorsal-related immunity factor (DIF) is the only component of the Toll pathway not yet reported in any tick species.

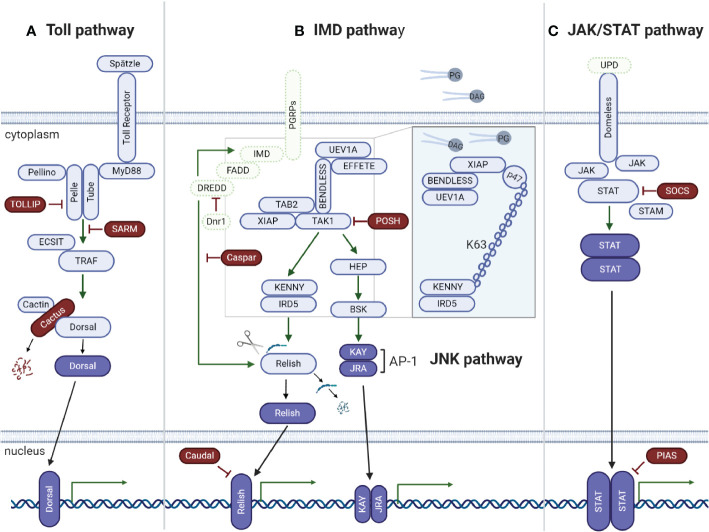

Figure 2.

Tick signaling-related genes in the three main immune signaling pathways of arthropods: (A) Toll, (B) IMD, and (C) JAK/STAT. (A) A previous in silico study (31) showed that components of the Toll signaling pathway of arthropods are conserved in ticks: extracellular cytokine Spatzle (Spz), transmembrane cytokine receptor Toll, Toll-interacting protein (TOLLIP), adaptor protein MyD88, kinases Tube (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 or IRAK4), Pelle (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 or IRAK1), Pelle-interacting protein Pellino, TNF receptor associated factors (TRAFs), evolutionarily conserved signaling intermediate in toll pathway (ECSIT), sterile alpha- and armadillo-motif-containing protein (SARM), Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factor Dorsal, Dorsal inhibitor protein IkappaB Cactus (IkB), and interacting protein Cactin of the IkB. (B) Regarding the IMD pathway, genes encoding downstream members of both the NF-kB/Relish and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) branches were identified: peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs), enzymes involved in ubiquitination (UEV1a, Effete/Ubc13 and Bendless/Ubc5), X-linked inhibitor apoptosis protein (XIAP), negative regulators Caspar (Fas-associating factor 1) and POSH (E3 ligase Plenty of SH3), transforming growth factor-beta activated kinase 1 (TAK1), TAK1-binding protein 2 (TAB2), IRD5 and Kenny/NEMO (IKKγ), and Relish-like Rel/NF-kB transcription factor. The adaptor protein IMD (immune deficiency), its associated molecule FAAD (Fas associated protein with death domain), the caspase DREDD (death related ced-3/Nedd2-like) and Dnr1 (defense repressor 1) have not yet been described in ticks. Components of the JNK branch of the tick IMD pathway include mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase hemipterous (HEP), Jun-kinase basket (BSK), activator protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factors JRA (Jun-related antigen) and KAY (Fos-related antigen, Kayak). Some IMD pathway components were functionally characterized by (48) (Insert). The authors showed that the IMD pathway is activated by PODAG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl diacylglycerol) or POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol). Once activated, XIAP interacts with the heterodimer Bendless : UEV1a, leading to the ubiquitination of p47 in a K63-dependent manner. Ubiquitylated p47 connects to Kenny (also named NEMO) and induces the phosphorylation of IRD5 and Relish. (C) Components of the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway are also conserved in ticks: the transmembrane cytokine receptor Domeless, tyrosine kinase JAK (Hopscotch), transcription factor STAT, signal transducing adaptor molecule (STAM) and the inhibitor proteins PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STAT) and SOCS (suppressor of cytokine signaling). The ligand of the Domeless receptor (UPD gene) was not identified in ticks (C). Activated transcription factors are represented in dark blue; the immune signaling pathway components not yet described in ticks are represented in green.

How the tick Toll pathway operates is largely unclear. Rosa and collaborators showed that the Toll pathway components are differentially expressed in the tick cell line BME26, which is derived from the tick R. microplus, in response to live Anaplasma marginale and Rickettsia rickettsii (two obligate intracellular bacteria) and heat-killed Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), Enterobacter cloacae (Gram-negative bacterium) and Micrococcus luteus (Gram-positive bacterium) (31). Interestingly, heat-killed microorganisms upregulated the gene expression of the majority of the Toll pathway components, R. rickettsii upregulated some Toll pathway components and downregulated others, and infection with A. marginale (a pathogen naturally transmitted by R. microplus) downregulated most of the Toll pathway components. These results suggest that A. marginale may downregulate Toll pathway components in an attempt to favor vector colonization, which might correspond to coevolutionary adaptation. Of note, similar results were found for the IMD, JNK, and JAK/STAT signaling pathways (31). However, studies on the mechanisms used by this pathogen to overcome tick immune responses are warranted to confirm the authors’ hypothesis. In adult R. microplus, only Dorsal was downregulated in both the gut and salivary glands of A. marginale-infected ticks, while Relish and STAT remained unmodulated (49). Moreover, Dorsal silencing promoted an increase in the A. marginale burden as well as knockdown of Relish and STAT. However, while Relish dsRNA (dsRelish) specifically silenced Relish, this transcription factor was also downregulated in both the dsDorsal and dsSTAT groups, which might explain the increase in the A. marginale load in these two groups as well. To determine the pathway responsible for infection control, the gene expression of specific effectors of each immune signaling pathway, which are currently unknown, is warranted. As Dorsal-, Relish-, and STAT-encoding genes do not exhibit significant sequence similarity, the authors suggested the existence of putative crosstalk among the Toll, IMD, and JAK/STAT signaling pathways (49) (Figure 3C). Nonetheless, an off-target effect cannot be ruled out. It is also possible that the knockdown of immune signaling transcription factors exerts an effect on the gut microbiota, which, in turn, may modulate their gene expression. In contrast to the results obtained with R. microplus, gene silencing of Toll (ISCW018193) did not exhibit any effect on the Anaplasma phagocytophilum burden in the salivary glands of I. scapularis nymphs (53). However, gut colonization was not evaluated; therefore, it is not possible to guarantee that the Toll pathway is not involved in controlling A. phagocytophilum infection in this tick species. In a study carried out with I. ricinus cells (IRE/CTVM20), it was shown that the expression of a Toll gene (homologous to the Toll ISCW022740 of I. scapularis) is upregulated after 72 and 120 h of infection with flaviviruses [tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) and louping ill virus (LIV)] but remained unmodulated in response to A. phagocytophilum (54). Conversely, infection with these flaviviruses downregulated the expression of three other Toll transcripts (homologous to ISCW017724; ISCW007727; ISCW007724 of I. scapularis), while Toll ISCW00727 expression was downregulated by A. phagocytophilum (54). The expression of another component of the Toll pathway, MyD88, was also downregulated by infection with these three pathogens, suggesting that they might suppress this pathway to promote vector colonization. To confirm this hypothesis, it is necessary to functionally characterize the role played by Toll components in pathogen proliferation.

Figure 3.

Immune pathway crosstalk. (A) In Drosophila, the DIF-Relish heterodimer activates the expression of both Toll and IMD pathway effectors, resulting in a stronger response against infection (50). (B) In Culex, after recognition of West Nile virus (WNV) dsRNA by Dcr-2, TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF) stimulates Relish, upregulating Vago expression (51, 52). Vago is then secreted by the infected cell and activates the JAK/STAT pathway in adjacent cells, upregulating the expression of antiviral genes. (C) In R. microplus, knockdown of Dorsal downregulates both Dorsal and Relish expression in salivary glands, while the levels of all the transcription factors remain unaltered in the gut. Relish is also downregulated in the gut and salivary glands of STAT-deficient ticks. Conversely, knockdown of Relish results in the specific silencing of its target gene in both the gut and salivary glands (49).

The Unconventional Immune Deficiency Pathway

In Drosophila, bacterial infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria and certain Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus and Listeria species, are mainly controlled by the IMD pathway through the recognition of diaminopimelic acid (DAP)-type PGN, which is present in the bacterial cell wall, by PGN-recognition proteins (PGRPs) (44, 55). Genomic and in silico studies have shown that ticks lack orthologs of many key elements of the IMD pathway, including the transmembrane PGRP, the Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), the adaptor molecule IMD, and the death-related ced-3/Nedd2-like protein (DREDD) (31, 33, 38, 48) (Figure 2B). Losses of IMD pathway components are not exclusive to ticks since they have also been described in other arachnids and hemipterans (30, 56). Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that some arthropods have unusual gene architectures, resulting in inaccurate annotation due to the use of software based on standard gene structures, as reported for the kissing bug Rhodnius prolixus (57). Gathering data from the genome and transcriptome associated with reciprocal BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) and hidden Markov model profile searches, the authors showed that most of the missing IMD pathway components are present in this hemipteran. Therefore, it is possible that the missing IMD pathway components might be a consequence of incorrect annotations due to structural divergences. Indeed, assays showed that the IMD cascade is functional in the insect fat body and is predominantly responsive against Gram-negative bacterial infection (57).

Despite missing several elements, the tick IMD pathway is functional and responsive to distinct pathogens (48, 49, 58). RNAi silencing of several IMD pathway components, including Bendless, ubiquitin E2 variant 1A (UEV1a), Relish, and Caspar (Figure 2B, insert), showed that this cascade controls A. phagocytophilum and B. burgdorferi burden in I. scapularis nymphs (48). In contrast to the classical Drosophila model of DAP-PGN recognition by PGRPs (44, 55), glycerophospholipids from bacterial membranes, including 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl diacylglycerol (PODAG), were reported to act as PAMPs for IMD pathway activation in ticks (48) (Figure 2B, insert). However, the mechanisms of POPG and PODAG recognition remain unclear, but it is hypothesized that they are sensed by a yet uncharacterized pattern-recognition receptor. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is an upstream signaling component of the IMD pathway and, when activated, specifically and directly interacts with the heterodimer E2 conjugating enzyme complex Bendless : UEV1a (48). Upon microbial activation, XIAP, together with Bendless : UEV1a, binds and ubiquitylates its p47 substrate in a K63-dependent manner. Ubiquitylated p47 connects to Kenny (also named NEMO) and induces, by a yet unknown mechanism, phosphorylation of the inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK) β (also known as IRD5) and Relish, the IMD transcription factor. Consequently, Relish is cleaved and translocated to the nucleus (58) (Figure 2B, insert). On the other hand, RNAi knockdown of two other components of the IMD pathway, transforming growth factor-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and TAK1 adaptor protein 1 (TAB1) (Figure 2B), presented no effect on the A. phagocytophilum burden in the salivary glands of I. scapularis nymphs (53). Therefore, studies carried out by Dr. Pedra’s group (48, 58) showed how the IMD pathway is activated in ticks, which is highly relevant since there is a lack of components in this pathway, different from the classic Drosophila model (44). However, the effector molecule(s) regulated by the IMD pathway that control(s) infections by pathogens such as A. phagocytophilum and B. burgdorferi still need to be identified.

In adult R. microplus, RNAi silencing of immune signaling of the Toll, IMD, and JAK/STAT pathway transcription factors identified the IMD pathway as the main controller of A. marginale infection in the tick gut and salivary glands (49). The expression of the genes encoding the AMPs microplusin, defensin, ixodidin, and lysozyme was analyzed in the gut and salivary glands of R. microplus after knockdown of Relish and infection with A. marginale. Interestingly, only the microplusin transcript levels were downregulated in dsRelish ticks, implicating this AMP as an effector of the IMD signaling pathway, which may act against A. marginale (49). However, although microplusin appears to be under IMD pathway regulation, possible coregulation by the JAK/STAT pathway cannot be discarded (49).

The other branch that constitutes the IMD pathway is JNK signaling (Figure 2B). In Drosophila, JNK has been shown to be involved in a wide range of biological processes, including cellular immune and stress responses, but it seems to not be required to induce AMP gene expression (59). Although activation of both the JNK and Relish branches of the IMD pathway occurs via TAK1 in Drosophila (59), additional studies are warranted to determine the activation of JNK pathways in ticks (48, 53, 58).

JAK/STAT Pathway: Just a Support Molecular Circuit?

In Drosophila, the JAK/STAT signaling pathway only plays an indirect role in controlling bacterial and fungal infection. Therefore, this pathway is considered a support circuit to the Toll and IMD pathways; however, it is especially sensitive to viral infections (60). Beyond its effects on the immune response, the JAK/STAT signaling pathway also regulates multiple biological processes, including repair and renewal of the gut epithelial layer (61), a function that was also reported to occur in ticks (62).

Although still poorly understood, the tick JAK/STAT pathway (Figure 2C) was reported to be functional, playing an important role in the control of pathogens (53, 62, 63). However, it is not clear how ticks activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, as the unpaired (Upd) encoding gene, a cytokine-like signaling molecule ligand of the transmembrane receptor Domeless, is missing. In I. scapularis, knockdown of the transcription factor STAT and JAK yielded evidence that this pathway is key to the control of A. phagocytophilum infection (53). The results also showed that the 5.3-kDa AMP is an effector regulated by the JAK/STAT pathway, which is essential to restrict A. phagocytophilum proliferation in tick salivary glands and hemolymph but not in the gut, indicating that additional effectors under JAK/STAT pathway regulation are required in this organ (53). Interestingly, it was reported that I. scapularis employs a sophisticated immune strategy that uses a vertebrate host-derived cytokine to stimulate its own JAK/STAT immune pathway (63). During feeding, the interferon-gamma (INFγ) acquired within the infected bloodmeal activates STAT by a yet unknown receptor and, through mediation of a Rho-like GTPase, leads to the synthesis of the AMP domesticated amidase effector 2 (Dae2), limiting the level of B. burgdorferi. Other evidence that indicates that the JAK/STAT pathway is associated with the regulation of AMPs was reported by Capelli-Peixoto and collaborators in adult R. microplus (49). The authors observed the downregulation of the AMPs ixodidin and lysozyme in the salivary glands and defensin in the gut and salivary glands of STAT-deficient ticks.

Effectors from signaling pathways, such as JAK/STAT, can act as either positive or negative regulators of infection. As presented above, Dae2 (63) and the 5.3-kDa AMP (53) are negative regulators, as they control pathogen proliferation. In contrast, peritrophin-1, another effector from the tick JAK/STAT pathway, was reported to increase B. burgdorferi survival in the gut of I. scapularis nymphs (62). Knockdown of STAT had a direct impact on the gut epithelium, affecting its mitotic activity as well as decreasing peritrophin-1 expression, which consequently disrupted the structural integrity of the peritrophic matrix (62). Therefore, peritrophin-1, which is a component of the peritrophic matrix, favors B. burgdorferi establishment (62). Interestingly, peritrophin-1 exhibits the opposite effect on A. phagocytophilum, another pathogen naturally transmitted by I. scapularis (64). Infection with A. phagocytophilum upregulates a tick antifreeze glycoprotein, which, in turn, alters bacterial biofilm formation and, consequently, disturbs the natural gut microbiota. This microbiota alteration affects the integrity of the peritrophic matrix, favoring pathogen colonization (64). Knockdown of peritrophin-1 and, therefore, the reduction in the thickness of the peritrophic matrix increases the A. phagocytophilum load in the tick gut (64).

RNAi as a Tick Innate Immunity Component

RNAi is a biological process that plays an important role in the defense of arthropods against viruses and transposable elements. Four main RNAi-related pathways have been described based on the origin of the activating small RNAs. The origin of three of these small RNAs is endogenous [microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (endo-siRNA), and piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA)], while the origin of the fourth is exogenous (siRNA) (65). The exogenous siRNA pathway is especially important and has been proposed to be the main antiviral response in Drosophila and mosquitoes (66). In general, after infection, long viral dsRNA is recognized and cleaved by Dicer-2 (Dcr-2) into 21 nucleotide (nt) siRNAs, known as viRNAs (65, 66). These viRNAs are then transferred to Argonaute-2 (Ago2), which couples to other members of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Only one strand of the viRNA remains coupled to RISC and guides the degradation of complementary viral RNA (65, 66). miRNAs use a similar mechanism, although involving Dcr-1 and Ago-1 (67).

The genome of I. scapularis exhibits significant gene expansion in RNAi elements, including five Ago homologous genes: Ago-78, homologous to insect Ago-1, and Ago-96, -68, -16, and-30, homologous to insect Ago-2 (68). Additionally, two Dcr genes, Dcr-89 and -90, were clustered with Drosophila Dcr-2 and -1, respectively. Similar gene expansion was identified in Hyalomma asiaticum RNAi components (viz., two copies of Dcr-2 and five copies of Ago-2) (69). Infection of I. scapularis IDE8 cells with Langat virus (LGTV) showed that Ago-16 and Ago-30 neutralized both LGTV and its replicon, as well as Dcr-90, despite the clustering of the last element with insect Dcr-1, which is involved in miRNA processing but not in siRNA (68). Shortly thereafter, knockdown of Ago-30 and Dcr-90 confirmed their antiviral role upon LGTV infection in I. scapularis IDE8 and I. ricinus IRE/CTVM19 cell lines (70).

Interestingly, viral or endogenous siRNAs were shown to be mostly 22 nt in length depending on the tick (68), in contrast with Drosophila and mosquito viRNAs and endo-siRNAs, which contain 21 nt (66). Moreover, these viRNAs mapped at the highest frequency around the 5’ and 3’ UTRs of the viral genome and antigenome (68). The 3’ UTRs of LGTV and TBEV express subgenomic flavivirus RNAs (sfRNAs), which are a counterdefense against the tick RNAi system, assuring vectorial competence (68). Of note, sfRNAs are expressed by almost all Flaviviridae members as an evolved balance between arthropods and viruses (67).

Grubaugh and collaborators (71) validated the in vitro data previously obtained by Schnettler et al. (68), showing that most viRNAs are, indeed, 22 nt in length and originate from the UTR of the viral genome and antigenome of I. scapularis in its life stages (larvae, nymphs, and adults) naturally infected with Powassan virus (POWV) (71). Moreover, the viral genetic diversity in ticks is lower than that in mice, suggesting that ticks exert stronger viral control than their vertebrate hosts. Therefore, POWV evolution seems to depend on RNAi-mediated diversification and selective constraints (71).

Regarding endogenous miRNAs, recent studies have shown that pathogens, such as viruses (72) and bacteria (73), modulate tick miRNA profiles, with a potential role in controlling pathogen replication within the vector (72, 73). On the other hand, the piRNA response to infection is still unknown in ticks. Nonetheless, the piRNA response has been implicated in the response of mosquitoes to viral infections (74, 75). Moreover, Hess and colleagues (76) suggested that the mosquito piRNA response precedes the RNAi-Dcr-2-dependent (siRNA) response during viral infection. In contrast with siRNAs, piRNA activation seems to be mediated by single-stranded RNAs that are Dcr1- and Dcr2-independent and possibly mediated by the endonuclease activity of Piwi proteins, resulting in 24–30 nt small RNAs, as found in Drosophila. In addition to antiviral activity, piRNAs seem to have important roles in controlling the activity of transposable elements in the genome and in the development of reproductive tissues (65). Considering the knowledge of the role played by RNAi in the defense of insects against infections, the tick RNAi system represents a wide and still unexplored field awaiting investigation.

Independent Immune Pathways or Dynamic and Indispensable Crosstalk?

Although the term crosstalk is commonly applied to the arthropod immunity literature, its definition remains conflicting, and in many cases, the mechanism by which it occurs remains unknown. Here, we consider crosstalk to occur when (i) the same effector is regulated by more than one immune signaling pathway (50, 56, 77) and (ii) the components of a specific immune signaling pathway modulate the components of other pathways (49, 51, 52, 78–80).

The regulation of AMP expression by Toll and IMD pathways was initially established in Drosophila, as well documented in the historical review by Imler (24). Originally, it was accepted that AMPs were regulated by a specific immune pathway; however, subsequent studies carried out by different research groups showed that this regulation was more complex than initially known, and crosstalk among immune pathways could occur, as described in the examples below. Although AMPs are mostly regulated by either Toll or IMD pathways in Drosophila, it has been reported that some AMP-encoding genes can be activated synergistically by both immune pathways (50) (Figure 3A). It was shown that the NF-κB transcription factors Dorsal, DIF, and Relish can dimerize as homo- or heterodimers with varying degrees of efficiency. The DIF-Relish heterodimer mediates the crosstalk between the Toll and IMD pathways, resulting in the activation of effectors from both pathways and, consequently, targeting a broader spectrum of infectious microorganisms (50).

Another example of a certain effector being regulated by more than one immune pathway occurs in the hemipteran stinkbug Plautia stali (56). As shown by Nishide and collaborators, knockdown of IMD, as well as Toll pathway components, modulates effectors of both pathways. Interruption of both pathways at the same time had a more conspicuous effect on AMP production, strengthening crosstalk (56). The authors proposed an intriguing hypothesis that the redundancy between these two immune signaling pathways may have predisposed them to and facilitated the loss of some IMD-related genes in P. stali.

The crosstalk between RNAi and immune signaling pathways has been shown in recent publications (51, 52, 78, 79). In Culex mosquitoes, Dcr-2, a central component of the siRNA pathway, recognizes West-Nile virus (WNV) dsRNA and activates a signaling cascade to stimulate Relish via tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor (TRAF) to increase Vago expression (Figure 3B) (51, 52). Following this transcriptional upregulation, Vago is secreted from infected cells and acts as a vertebrate cytokine functional homolog, binding to a still unknown cellular receptor in surrounding cells and triggering the JAK/STAT pathway. Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway ultimately results in an appropriate antiviral response in uninfected cells, such as upregulation of vir-1 and other antiviral genes. These studies thereby revealed a paracrine signaling response mediated by a complex network of crosstalk, opening up several intriguing lines of investigation for future studies on arthropod immunity. Other studies have shown crosstalk between RNAi and the Toll pathway in Ae aegypti Aag2 cells (78) and Drosophila (79). In the first study, the miRNA aae-miR-375 upregulated Cactus, inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB transcription factor and reducing AMP synthesis, consequently enhancing dengue virus (DENV) infection (78). In Drosophila, on the other hand, four distinct members of the miR-310 family directly regulate drosomycin expression, a Toll-derived AMP (79). In addition to the connection between RNAi and signaling pathways, the redundancy of distinct miRNAs cotargeting the same transcript highlights the tight regulation imposed by miRNAs on the innate response.

It was also shown that the transcription factors activator protein 1 (AP-1; from the JNK pathway) and STAT neutralize Relish-mediated activation during the innate immune response in Drosophila, which is necessary for a proper and balanced immune response. The mechanism for controlling Relish-mediated transcriptional activation is through the formation of a complex composed of AP-1 and STAT with the dorsal switch protein (Dsp1), which recruits a histone deacetylase to prevent Relish transcription (80).

In ticks, to the best of our knowledge, there is only one study reporting putative crosstalk among the immune signaling pathways, which was reported by Capelli-Peixoto and collaborators (49). The authors showed that knockdown of the transcription factors Dorsal, Relish, or STAT downregulates Relish expression (Figure 3C), with a consequent increase in the A. marginale load in R. microplus salivary glands. In contrast, Dorsal-deficient ticks presented no effects on Relish expression in the gut, where, intriguingly, ticks exhibited only modest silencing of Dorsal itself. Relish levels were also diminished in STAT-deficient guts. Only treatment with dsRelish resulted in specific silencing of its target gene in both the gut and salivary glands (Figure 3C). Nonetheless, the A. marginale burden was higher in the gut of ticks from all groups (dsDorsal, dsRelish, and dsSTAT) than in the control (49). As similarities among Dorsal, Relish, and STAT gene sequences were insignificant, the authors hypothesized that crosstalk of the immune pathways in ticks might occur to enhance the immune response. However, an off-target effect cannot be completely disregarded. Although the regulation of AMPs by the IMD and JAK/STAT pathways has been established, as already described above, it is still necessary to silence AMP-encoding genes to assign their role in A. marginale control. Therefore, the tick immune system, as shown in some insects, is also integrated, versatile, and possibly capable of making a network of connections among innate signaling pathways, giving rise to effective antimicrobial responses.

Antimicrobial Peptides: May the “Source” Be With You!

AMPs are important effectors of the immune systems of both invertebrates and vertebrates, having a broad spectrum of activity against microorganisms (81). In ticks, the main sites of AMP expression are hemocytes, fat body, gut, ovaries, and salivary glands, where they can be modulated in response to either blood feeding or microbial challenge (82). Several reviews of tick AMPs addressing their characterization, as well as their interaction with microorganisms, have been published in the last decade (11, 33, 83, 84).

Interestingly, ticks use host hemoglobin, one of the most abundant proteins within the blood meal, as a source for the production of antimicrobial-derived fragments (85–88). Hemoglobin-derived AMPs, referred to as hemocidins (89), are produced by the proteolytic activity of aspartic and cysteine (catepsin-L like) proteinases from the tick gut (90). Structural studies with the synthetic amidated hemocidin Hb33-61a of R. microplus showed that its α-helical C-terminus is responsible for the permeabilization of the microbial membrane (91). However, it is still unknown whether hemocidins act intracellularly or if they are released to the tick gut lumen, where they can fight against microorganisms.

In addition to hemocidins, ticks also produce endogenous (ribosomally synthesized) AMPs (11, 83). Among the several tick AMPs identified to date, microplusins (also known as hebraeins) are among the most well characterized. Microplusin is a cysteine- and histidine-rich AMP that was first isolated from the hemolymph of adult R. microplus (92) and Amblyomma hebraeum (93). Microplusin was also identified in the ovaries and eggs of R. microplus (94), suggesting that in addition to protecting adults, it may also play a role in the protection of embryos before and after oviposition. Microplusin exhibits an α-helical globular domain and chelates metal ions (95). The bacteriostatic activity of microplusin against the Gram-positive bacterium M. luteus was reversed by the addition of copper II but not iron II. Indeed, microplusin interferes with the respiration (a copper-dependent process) of both M. luteus (95) and the fungus Cryptococcus neoformans (96). Microplusin was also reported to affect melanization and capsule formation, which are important virulence factors of C. neoformans (96). Interestingly, knockdown of microplusin increased the load of R. rickettsii in Amblyomma aureolatum (97). On the other hand, this AMP had no effect on either rickettsial transmission or tick fitness. Defensins compose another class of AMPs that have been described in several tick species, displaying activity against different types of microorganisms [for review, see (11, 83)]. For example, defensin-2 of Dermacentor variabilis was shown to protect against another bacterium of the genus Rickettsia, R. montanensis, as its neutralization with antidefensin-2 IgG increased the rickettisal load in the tick gut (98). Defensin-2 causes permeabilization of the bacterial membrane with consequent leakage of cytoplasmic proteins (98).

Dae2 is an AMP of I. scapularis that was acquired by horizontal bacterial gene transfer and has become an important effector to control B. burgdorferi infection (99), although it does not exhibit direct action on this pathogen (63). Indeed, it was recently shown that Dae2 is physically unable to overcome the outer membrane structure of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria; thus, it does not present lytic activity against B. burgdorferi, suggesting the need for other factors, such as membrane-permeabilizing agents (100). As Dae2 is delivered to the vertebrate host bite site via saliva and exhibits strong activity against bacteria usually encountered in the host skin, this AMP may protect ticks from the acquisition and proliferation of host skin microbes (100).

Serine proteinase inhibitors have also been reported to play a role in the arthropod immune system. For instance, serine proteinase inhibitors mediate both coagulation and melanization processes of hemolymph and the production of AMPs (101). In addition, serine proteinases may also exert antimicrobial activity, possibly inhibiting proteinases that microorganisms use to colonize host tissues and evade the immune system (102). The first report of a tick serine proteinase inhibitor with antimicrobial properties was the ixodidin of R. microplus (103), which presents the key features of trypsin inhibitor-like domain proteins (104). Interestingly, one Kunitz inhibitor was reported to control R. montanensis infection in the gut of D. variabilis (105). In contrast to defensin, D. variabilis Kunitz-type inhibitors present a bacteriostatic effect on R. montanensis (106). Therefore, serine proteinase inhibitors are also used by ticks as powerful antimicrobial molecules.

Despite the diverse nature of molecules used by ticks as antimicrobials, little information on their synthesis regulation is available, as discussed above. Therefore, additional studies on the regulation of tick AMPs by immune signaling pathways are required to better understand their role in the control of distinct pathogens.

Redox Metabolism as an Important Player in the Infection Control Orchestra

In addition to AMPs, triggering of the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in response to infection has been described in several arthropods, such as Drosophila (107) and mosquitoes (108). ROS have an essential role in infection-related physiological as well as pathophysiological processes, such as signaling, regulation of tissue injury and inflammation, cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (109, 110).

In ticks, there is still little available information on ROS metabolism and their impact on pathogen control. Nonetheless, it is recognized that hemocytes produce ROS under stimulation. Gram-positive bacteria, zymosan, and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate elicit the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide () by hemocytes of R. microplus (111). In contrast, stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the major component of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane, failed to induce ROS generation, indicating that different mechanisms or roles for ROS upon infection with either Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria may exist (111). Further studies with R. microplus showed that cytochrome c oxidase subunit III (COXIII), an enzyme of mitochondrial electron transport complex IV involved in mitochondrial ATP and ROS generation, is important for the transmission of A. marginale to calves (112). It is possible that COXIII knockdown imbalances tick redox metabolism, affecting its ability to transmit this pathogen (112). The peroxiredoxin Salp25D from I. scapularis had no effect on the transmission of B. burgdorferi but instead played a role in spirochete acquisition by the tick (113). RNAi-mediated silencing of Salp25D affects bacterial acquisition by ticks fed on B. burgdorferi-infected mice. The same effect was obtained when ticks were fed on Salp25-immunized mice (113). It is possible that Salp25 may detoxify ROS at the tick feeding site and gut, thus affording a survival advantage to B. burgdorferi.

In the mosquito An. gambiae, an extracellular matrix crosslinked by dityrosine covalent bonds catalyzed by dual oxidase (DUOX) and heme peroxidase is located in the gut ectoperitrophic space (between the epithelial cell layer and the peritrophic matrix). This extracellular matrix acts as an additional physical barrier to decrease gut permeability to bacterial PAMPs, impairing immune response activation by the resident microbiota (114). Importantly, the dityrosine network also provides a favorable environment for Plasmodium development, as it prevents the activation of nitric oxidase synthase (iNOS), a nitric oxide-generator enzyme (114). iNOS is responsible for parasite nitration, a key step in the action of the antiplasmodium complement-like molecule TEP1. Later, it was shown that the heme peroxidase 2/NADPH oxidase 5 system plays a central role in epithelium nitration, therefore potentiating the antiparasitic effect of nitric oxide (115). Similar to An. gambiae (114), an extracellular matrix was described in the tick I. scapularis, which acts as a shield that favors B. burgdorferi survival and indirectly prevents the induction of borreliacidal agents in the tick gut (116).

Intriguingly, A. marginale upregulated the genes encoding antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione S-transferase, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, and peroxiredoxin, whereas genes encoding ROS-generating enzymes, such as DUOX and endoplasmic reticulum oxidase, were downregulated in R. microplus-derived BME26 cells (117). Conversely, R. rickettsii and heat-killed S. cerevisiae, E. cloacae or M. luteus triggered the opposite gene expression pattern (117). Furthermore, simultaneous RNAi knockdown of catalase, thioredoxin, and glutathione peroxidase, three representative members of the tick antioxidant enzymatic system, as well as the oxidation resistance 1 (OXR1), which regulates the expression of ROS detoxification enzymes, decreased A. marginale infection (117). Therefore, while BME26 cells respond to infection, producing an oxidant environment, A. marginale seems to subvert this response to create an antioxidant environment, which is required for its survival (117). It is possible that A. marginale manipulates R. microplus redox metabolism (and production of immune signaling pathway effectors, as aforementioned) to favor its proliferation. Additional studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms that this bacterium uses to subvert tick immune responses.

Cell-Mediated Immunity in Ticks

Hemocytes, which are sessile or circulating cells from arthropod hemolymph, are responsible for several immune responses. The nomenclature of hemocytes varies considerably depending on the arthropod species and/or the approaches of the study (118). Earlier morphological, ultrastructural, and physiological studies of the hemocyte repertoire in different tick species consistently reported the presence of three basic types of hemocytes, namely, phagocytic plasmatocytes and granulocytes and nonphagocytic granulocytes (119–121). These cells apparently differentiate from rarely occurring prohemocytes (120, 122). More recent studies have described additional types of tick hemocytes, namely, adipohemocytes in Rhipicephalus sanguineus (123) and spherulocytes and oenocytoids in R. microplus (122). The most important immune responses of arthropod hemocytes are phagocytosis, encapsulation, nodulation (which involves melanization by the PPO cascade), coagulation, and production of immune-related molecules.

The role of tick hemocytes in the phagocytosis of a variety of microbes, including bacteria, yeast, spirochetes, and foreign particles, has been investigated by several studies [for example, see (111, 124–127)]. By contrast, very little is known about the encapsulation and nodulation mechanisms. Indeed, there is only one report on encapsulation (128) and one on nodulation (129), both in D. variabilis. After the inoculation of ticks with Escherichia coli, hemocytes did not form circular layers but aggregated around the bacteria, which is a characteristic feature of nodule formation (129). As the encapsulation study was performed using an implant of Epon−Araldite under the tick cuticle, it is still unknown whether it also occurs against microorganisms (128).

In invertebrates such as insects and crustaceans, hemocytes produce components of the melanization response, which involves an enzymatic cascade referred to as the PPO activating system, ultimately resulting in the production of melanin (130, 131). This process can be locally activated by cuticle injury or systemically triggered by microbial invasion of the hemocoel. Interestingly, in the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera, infection with the baculovirus HearNPV decreased the levels of the majority of PPO cascade components, while serpin-9 and serpin-5 (which were also shown to regulate the proteases cSP4 and cSP6, respectively) were increased (132). In addition, in vitro assays showed that hemolymph melanization can kill baculovirus, an effect abolished by the specific PO inhibitor phenylthiourea. Together, the results suggest that baculovirus inhibits the melanization response to ensure its survival in H. armigera (132). There is no evidence of the existence of the PPO cascade in ticks based on available genomic and transcriptomic data. In line with this, no PPO activity has been reported to be present in the hemolymph of the hard ticks Amblyomma americanum, D. variabilis, and I. scapularis (133). In contrast, two studies reported PPO-like activity using L-DOPA as a substrate in the hard tick R. sanguineus (134) and in the soft tick Ornithodoros moubata (135). However, the enzymes responsible for such activity have not yet been identified, and enzymatic assays did not employ phenylthiourea as a control.

Coagulation is another important immune response of arthropods. The final product of coagulation is a protein clot, which is essential to avoid the loss of hemolymph in cases of an injury and the spread of an invader microorganism throughout the hemocoel (136). In horseshoe crabs, the clotting process involves a serine-protease cascade that leads to the activation of the clotting enzyme that converts the coagulogen into the insoluble clot (137), while in crayfish, the process depends on direct transglutaminase (TG)-mediated cross-linking of a specific plasma protein homologous to vitellogenins (19, 136). TG is also involved in the final step of coagulation in horseshoe crabs, cross-linking coagulin with hemocyte surface proteins named proxins (138). Interestingly, factors of the coagulation cascade interact with hemocyanin, causing it to present PO activity in the horseshoe crab Tachypleus tridentatus, demonstrating crosstalk between melanization and coagulation cascades (139). In Drosophila, coagulation and PO activity were also described to be tightly associated (140). Wound sealing in flies involves two steps: in the first step, TG-mediated crosslinking of hemolymph proteins occurs, and in the second step, PO-dependent crosslinking takes place, hardening the clot and producing melanin. In ticks, putative coagulation was uniquely reported for D. variabilis, where a fibrous matrix was observed around an inert implant (128). TGs and proclotting enzyme precursors have been detected in tick genomes (33). Moreover, an injury-responsive multidomain serine protease homologous to Limulus Factor C has been characterized in I. ricinus (141). Therefore, additional studies based on appropriate in vitro assays are needed to ultimately resolve the question of the existence of hemolymph clotting in ticks.

Tick hemocytes (83), as well as the hemocytes of other arthropods, such as mosquitoes (142), also produce a series of immune-related molecules. Intriguingly, the hemocytome of I. ricinus showed that only 1.48% of the 15,716 coding sequences (CDSs) identified were related to immune factors (143). Of the identified CDSs, 327 were five times more highly expressed in hemocytes than in salivary glands and the gut, among which 11 encode immune factors, including AMPs and proteins involved in pathogen recognition. As presented in this section, hemocytes are versatile components of the arthropod immune system that play diverse and key roles. The principal insect tissue that produces the majority of soluble immune molecules in hemolymph is the fat body (44). The role of tick fat body in the tick immune system requires further investigation.

The Primordial Complement System of Ticks

One important branch of both cellular and humoral innate immunity in vertebrate and invertebrate metazoan organisms is carried out by the complement system. In higher vertebrates, the complement system is composed of approximately thirty components arranged in classical, lectin, and alternative pathways, which recognize foreign cells (microbes), specifically tag them via opsonization, and ultimately, eliminate them via phagocytosis or cell lysis (144). The common denominator of all three pathways is the proteolytic activation of the central C3 complement component. The occurrence of this molecule can be traced back in most ancient invertebrates, such as horseshoe crabs (subphylum Chelicerata, class Merostomata), implying that an ancestor of the complement system existed on Earth for more than 500 mil. years (145, 146). For ticks, which are also chelicerates, advanced knowledge of the primitive complement system of horseshoe crabs gathered during the past two decades presents the best matching comparative model (137, 145, 147).

Microbial pattern recognition by the vertebrate lectin pathway is mediated by multimeric mannose-binding lectins (MBLs) or ficolins. The horseshoe crab counterparts of mammalian ficolins are lectins named tachylectin-5 or carcinolectin-5 (148–150). These lectins share a fibrinogen-related protein (FRED) with ficolins but lack the N-terminal collagen-like domain responsible for forming complexes with MBL-associated serine proteases (MASPs) (151), which are absent in arthropods (146). The lectin Dorin M, purified from the plasma of the soft tick O. moubata (152), was shown to be a clear ortholog of the horseshoe crab tachylectins-5 (153), and similarly to ficolins and tachylectins, it forms high molecular weight multimers in the native state (152). The search for homologous lectins in I. ricinus (154) and in the genome of I. scapularis (155) revealed the existence of two phylogenetically distinct families, further referred to as ixoderin A and ixoderin B (Figure 4). Ixoderin A is mainly present in plasma and is responsible for the hemagglutination of mouse erythrocytes (155). On the other hand, the salivary gland transcriptomes of I. ricinus (157, 158) indicate that ixoderin B represents a highly variable multigene family that is preferentially expressed in the salivary glands and secreted into saliva. The function of these FREPs in tick saliva is still obscure, but we can hypothesize that they may play a role in the recognition of a specific tick host.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of tick complement-related molecules (TEPs, convertases, lectins). Invertebrate TEPs are divided into four groups: panprotease inhibitors of the α2-macroglobulin type (α2M); C3-like complement components (C3); macroglobulin complement-related (MCR); and insect-type TEPs (iTEPs). IrA2M(1–3) represents I. ricinus α2M: IrA2M-1, 2 and 3; IrC3(1-3) represents I. ricinus C3: IrC3-1, IrC3-2, and IrC3-3; IrMCR (1,2) represents I. ricinus MCR: IrMcr-1 and IrMCR-2; and IrTEP represents I. ricinus iTEP. Other components of the I. ricinus primitive complement system are two putative convertases: IrFactor C, which shows the domain organization of the I. ricinus injury-responsive convertase related to Limulus Factor C (141), and IrC2/Bf, which shows the domain organization of the I. ricinus convertase related to the complement components C2 and/or Bf (156). Ixoderins A and B show the monomer structure of Ixodes sp. lectins related to ficolins (155). Domain abbreviations and nomenclature according to the NCBI conserved domain database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and symbols used in the figure: MG1, 3, 4 – macroglobulin domains 1, 3, 4; A2M_N – MG2 domain of α2-macroglobulins; A2M_N_2 – α2-macroglobulin family N-terminal region; Scissors – indicate the posttranslational cleavage site (not present in IrA2M-3); BR – bait region of α2-macroglobulins (variable by alternative splicing); ANAT – anaphylatoxin homologous domain (signature domain of C3-complement components); LD – low density lipoprotein class A domain (signature domain of MCRs); A2M_2/TED – thioester containing domain; Blue asterisks – thioester bond present; White asterisks – thioester bond absent in IrA2M-2 and IrMCR-1; A2M_r – α2-macroglobulin receptor domain; NTR_like – the signature C-terminal domain of C3,C4, and C5 complement components; ccccccccc – the cysteine-rich N-terminal region of Limulus Factor C; CCP – complement control protein module (aka short consensus repeats SCRs or SUSHI repeats); LCCL – LCCL domain; CLECT – C-lectin domain; Tryp_Spc – Trypsin-like serine protease; vWFA – Von Willebrand factor A domain; FReD – Fibrinogen-related domain.

The central effector molecules of vertebrate and invertebrate complement systems are proteins belonging to the thioester-containing protein (TEP) family, formerly referred to as proteins of the α2-macroglobulin superfamily (144, 159, 160). The TEP designation is given due to the presence of a highly reactive β-cysteinyl-γ-glutamyl thioester (TE) bond within a thioester domain. Invertebrate TEPs are divided into four major phylogenetically distinct groups: (i) panprotease inhibitors of the α2-macroglobulin type (α2M), (ii) C3-like complement components (C3), (iii) insect-type TEPs (iTEPs), and (iv) macroglobulin complement-related proteins (MCRs) (124, 146, 161). Genome-wide screening of the I. scapularis genome (124) and the recently available horseshoe crab genomes (162, 163), together with transcriptome data from a variety of arthropods, reveal that all these major groups of TEPs are present in chelicerates, but C3-like molecules are absent in crustaceans and hexapods, while α2Ms were lost in the evolution of some insect lineages, such as Drosophila and mosquitoes (146).

Orthologs of nine TEPs present in the I. scapularis genome (124) were identified in closely related I. ricinus (125), and their full CDSs were recently deposited in GenBank: IrA2M-1 (MT779788); IrA2M-2 (MT779789); IrA2M-3 (MT779790); IrTep (MT779791); IrC3-1 (MT779792); IrC3-2 (MT779793); IrC3-3 (MT779793); IrMcr-1 (MT779795); and IrMcr-2 (MT779796). The domain structure of tick TEP representatives is shown in Figure 4. The hallmark domain of α2Ms is the presence of the bait region (BR), which is cleaved by the target protease. Several bait region alternative splicing variants were reported in the α2M region of the soft tick O. moubata (164) as well as in IrA2M-1 of I. ricinus (165). IrTEP has a domain architecture quite similar to that of IrA2Ms; however, this molecule is phylogenetically more closely related to insect TEPs (124). Tick C3-like molecules (IrC3-1, IrC3-2, IrC3-3) possess two signature domains, namely, the anaphylatoxin domain and C-terminal NTR complement_C345C domain. The MCRs can be clearly identified based on the presence of the short low-density lipoprotein receptor domain (LD), which occurs in the central part of the molecule (Figure 4). Tick TEPs are specifically expressed in tick fat body (IrA2M-1, IrA2M-3, IrC3-1, IrC3-2, IrC3-3), tick hemocytes (IrA2M-2, IrA2M-3), salivary glands (IrC3-2, IrMcr-1), and ovaries (IrTEP) (125).

Other characterized components of the I. ricinus primitive complement system are two putative convertases: (i) IrC2/Bf (156), which is related to the vertebrate complement components C2 and/or FactorB (Bf) (144) and homologous to convertases from horseshoe crabs (145, 166), and (ii) IrFC (141), homologous to Limulus Factor C, which plays a dual function as the factor that triggers the clotting cascade upon sensing Gram-negative bacterial endotoxins and as an LPS-sensitive convertase of the horseshoe crab C3 complement component (147, 167). Both IrC2/Bf and IrFC are multidomain convertases that share the N-terminal trypsin-like domain and numerous CCP modules (complement control protein, aka sushi domains) (Figure 4). While IrC2/Bf is mainly expressed in the tick fat body and its expression is responsive to injection of the yeast Candida albicans and a variety of Borrelia species (156), IrFC is produced by tick hemocytes, and its expression is responsive to any injury, including injection of sterile phosphate-buffered saline, implicating its role in hemolymph clotting and wound healing (141).

RNAi-based functional studies of I. ricinus complement components successively deciphered their nonredundant roles in the phagocytosis of different microbes by tick hemocytes (124, 125, 141, 155, 156, 165). Phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria represented by the tick pathogen Chryseobacterium indologenes (168) depends mainly on the convertase IrFC, which seems to be linked to the IrC3-3 component. Interestingly, phagocytosis of this bacterium is also clearly mediated by α2Ms IrAM2-1 and IrAM2-2 by a yet unknown mechanism that likely involves the interaction of these macromolecular protease inhibitors with the potent metalloprotease secreted by the bacterium (168).

A distinct phagocytic pathway dependent on the convertase IrC2/Bf is responsible for the phagocytosis of the yeast C. albicans and spirochete Borrelia. Phagocytosis of C. albicans is further facilitated by IrC3-1 and IrMcr-2, consistent with the reported role of its related molecule MCR (DmTep6) in the phagocytosis of this yeast by Drosophila S2 cells (161). Similar to other Gram-negative bacteria, phagocytosis of Borrelia is also mediated by IrC3-3. Ixoderins A and B were found to be involved in the phagocytosis of all the tested microbes, except Borrelia. Although Borrelia afzelii (the principal Lyme disease-causative agent in Europe) is actively phagocytosed by tick hemocytes; neither RNAi-mediated silencing of any tick complement-related molecules nor the total elimination of phagocytosis by preinjection of latex beads have shown any effect on the transmission of these spirochetes to the host (126). These results indirectly support the recent finding that the transmission of B. afzelii from infected I. ricinus nymphs to naive mice avoids the tick hemocoel and salivary glands and occurs by a direct gut-to-mouthpart route (169). However, it is possible that the tick complement plays a role in the transmission of other tick-borne pathogens, such as intracellular bacteria, including Anaplasma spp. and Rickettsia spp., or protozoan parasites, including Babesia spp. These objectives await an intensive research focus in the future.

Regulated Cell Death as an Immune Defense

Regulated cell death (RCD) is widely distributed in nature, occurring in both unicellular and multicellular organisms (170). As extensively stated above, the arthropod innate immune system must coordinate pathogen recognition with effector mechanisms to successfully control infection. Nonetheless, over the past decade, several studies have established RCD processes as important mechanisms for the regulation of the immune response as well as the control of infections (171–173). Autophagy, apoptosis, and necrosis are the main types of RCD that have been described to be related to insect immunity in the last few years (173). In this section, we focus on autophagy and apoptosis and their interconnections with immune signaling pathways.

Autophagy is a highly conserved process in which endogenous material (misfolded proteins and aggregates, damaged organelles, and other macromolecules) or exogenous material (such as invading pathogens) are selectively recognized and sequestered within autophagosomes (double-membrane vesicles) that subsequently fuse with lysosomes, leading to cargo degradation (174). Autophagy is executed by a series of evolutionarily conserved autophagy-related (ATG) proteins that have orthologs in eukaryotic organisms ranging from yeasts to humans (174). Studies on Drosophila have provided excellent insights into the importance of autophagy during microbial infection (175). For instance, infection with the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes induces autophagy in both hemocytes and a hemocyte-derived Drosophila cell line (176). Interestingly, the IMD pathway receptor PGRP-LE is involved in bacterial recognition for autophagy activation. In addition, RNAi-mediated silencing of the autophagy genes atg5 and atg1 increases the bacterial load within cells, showing that this pathway is important to control infection. Autophagy is also important to control infection by vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in Drosophila (177, 178). In this process, the viral glycoprotein VSV-G is recognized by Toll-7, activating autophagy via a still unknown pathway that is independent of the canonical Toll, IMD, and JAK/STAT pathways (178). The role played by autophagy in the protection of mosquitoes against viruses is somewhat controversial, with reports suggesting both pro- and antiviral effects (179). In ticks, the expression of atg genes was upregulated under starvation in Haemaphysalis longicornis (180, 181), I. scapularis (182), R. microplus, and A. sculptum (183), correlating with the classical role of autophagy in stress. However, studies correlating tick autophagy with immune responses still need to be performed.

Apoptosis is another highly conserved RCD that is essential for removing damaged and infected cells to maintain homeostasis. There are two major apoptotic signaling pathways: extrinsic, also called death receptor pathway, and intrinsic, in which mitochondria play a central role (Figure 5). Both of these pathways culminate in the activation of executer caspases that are key for eliminating apoptotic cells (184). Apoptosis is activated in Drosophila by infection with Drosophila C virus (DCV), and infected cells are phagocytized by hemocytes in a phosphatidylserine-mediated process (185). Apoptosis can also control viral infection in mosquitoes (186, 187). Interestingly, the expression of proapoptotic genes was significantly higher in the refractory strain Cali-MIB of Ae. aegypti than in the susceptible strain Cali-S upon experimental infection with DENV-2, suggesting that apoptosis is involved in the distinct susceptibility of mosquitoes to infection (186). Apoptosis is also involved in the control of the proliferation of WNV in the midgut of a refractory strain of the mosquito Culex pipiens pipiens (187). Studies on the apoptotic response upon pathogen infection in ticks are also scarcer than those in insects. Infection of the I. ricinus cell line IRE/CTVM20 with the bacterium A. phagocytophilum and the flaviviruses TBEV and LIV upregulated the expression of apoptosis-associated components, such as cytochrome c and fatty-acid synthase (FAS) (54, 188).

Figure 5.

Components of apoptosis activation pathways identified in ticks. Apoptosis is triggered by two main pathways. The extrinsic pathway is activated by recognition of external stimuli by transmembrane death receptors, such as fatty acid synthase (FAS), leading to the activation of caspase-8. The intrinsic pathway, also known as the mitochondrial pathway, is activated by internal stimuli. Subsequently, mitochondrial channels composed, for example, of porins, allow the release of mitochondrial components, such as cytochrome c, to the cytosol, activating the initiator caspase-9. B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2) can inhibit cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Both pathways culminate in the activation of effector or executioner caspases, such as caspases -3 and -7, resulting in chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, degradation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins and protein cross-linking, which ultimately cause cell death.

To guarantee their replication and survival within the host cell, many pathogens, including viruses, bacteria and protozoa, subvert apoptosis induced by infection (189). For instance, infection with Zika virus (ZIKV) inhibits apoptosis in Ae. aegypti through the action of sfRNAs (190). Until very recently, the unique example of a pathogen that inhibits apoptosis in tick cells was A. phagocytophilum (188, 191, 192). This bacterium inhibits the intrinsic apoptosis pathway in I. scapularis salivary glands and ISE6 cells by porin (voltage-dependent anion-selective channel) downregulation, resulting in the inhibition of cytochrome c release. Nonetheless, while the intrinsic pathway is inhibited, the extrinsic pathway seems to be activated through the inhibition of FAS by an unknown mechanism as a possible attempt to limit bacterial infection (192, 193). Conversely, in the I. scapularis gut and I. ricinus IRE/CTVM20 cells, A. phagocytophilum supposedly inhibits apoptosis through upregulation of the JAK/STAT pathway (191). However, these conclusions were mostly based on transcriptomics and proteomics data, and only a few genes were functionally characterized by RNAi. In addition, the effectors that A. phagocytophilum uses to inhibit tick apoptosis have not been elucidated to date, as they have been for the manipulation of apoptosis in human neutrophils (194). Recently, it was reported that R. rickettsii downregulates negative regulators of apoptosis in the initial phase of BME26 cell infection, which are upregulated later. Infection also prevents the fragmentation of DNA and decreases the activity of caspase-3 as well as the exposure of phosphatidylserine. Remarkably, bacterial growth is higher in apoptosis-inhibited tick cells, suggesting that such an inhibitory effect is important to guarantee cell colonization (195).

Apoptosis is closely regulated by apoptosis inhibitor proteins (IAPs) (Figure 5) (196, 197). IAPs present at least two conserved motifs: baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) motifs, which are represented from one to three tandem repeats in the N-terminus, and the C-terminal really interesting new gene (RING) motif; this last motif presents E3-ubiquitin ligase activity. In Drosophila, the E3-ubiquitin ligase activity of DIAP-2 has been described as being important for the activation of Relish after recognition of Gram-negative bacteria (198–201). Knockdown of the XIAP of I. scapularis from the IMD pathway, which also possesses E3-ubiquitin ligase activity, increased colonization by A. phagocytophilum, showing that E3 is important for the control of infection (202) (see the above section “The unconventional IMD pathway”). However, it is still unknown whether XIAP plays a role in tick apoptosis.

Additional studies are warranted to better understand the role played by tick apoptosis pathway components in infection control and their interconnections with immune signaling pathways as well as the mechanisms that pathogens use to subvert the death of tick cells, thereby guaranteeing their survival and proliferation.

The Role of Tick Microbiota in Vector Competence

Ticks, as well as most multicellular eukaryotes, possess associated bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea, mainly in mucosal organs, composing their microbiota (203). In the last decade, several studies have focused on the bacterial composition of different genera of ticks and have explored the interaction of TBPs with nonpathogenic tick endosymbionts to elucidate the impact of microbiota on their vector competence (62, 64, 204–206). The tick immune responses to microbiota, despite its importance for a more comprehensive understanding of tick biology, is a field that requires attention since little is known in comparison with other arthropods. Therefore, in this section, we summarize the Ae. aegypti immune responses to the gut microbiota and relate this knowledge to ticks.

In adult mosquitoes, the IMD pathway is activated in response to microbiota proliferation induced by the blood meal, limiting Sindbis infection (207). ROS production is mediated by DUOX, whose expression is regulated by a gut membrane-associated protein named Mesh (208). However, a reduction in ROS due to heme release upon blood digestion protects the gut microbiota (209). To counteract the action of Relish-dependent AMPs, the gut microbiota stimulates the expression of C-type lectins (CLTs) in Ae. aegypti, which bind to bacterial cell walls, thereby protecting the bacteria (210).

In addition to the immune response to microbiota, there is interest in the impact of microbiota on the vector capacity of mosquitoes and ticks. In Ae. aegypti, several studies have shown that larval microbiota can influence vector competence in adult mosquitoes, playing a critical role in their response to viral infections (211). For instance, E. coli infection during the larval stage stimulates the production of AMPs and nitric oxide, protecting the mosquito from other infections (212). In addition, when Enterobacteriaceae bacteria are the only members of the larval microbiota, DENV infection in adults is reduced in comparison to Salmonella sp. as the only member (213). Conversely, exposure to pathogenic Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis in resistant larvae increases adult susceptibility to DENV [but not to Chikungunya (CHIKV)] (214), possibly due to changes in the microbial community (215).

Of all the bacteria present in insect microbiota, Wolbachia pipientis may be the most ubiquitous symbiont, as it is naturally present in 40% of all terrestrial arthropod species (216). Intracellular and maternally transmitted Wolbachia can cause pathogen interference (PI; the ability to reduce the chance of pathogen infection and decrease pathogen load) and cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI; when infected males mate with uninfected females, the hatch of eggs is heavily reduced), manipulating host reproduction and working as a genetic driver (the ability to spread through a population in a non-Mendelian way) (217). In Ae. aegypti, Wolbachia strongly reduces CHIKV, DENV and ZIKV infection and vector competence via the PI phenotype (217–220). For this reason, there is an ongoing program, the World Mosquito Program, to infect mosquito eggs with Wolbachia (from Drosophila – wMel) in the laboratory and release them in dengue-endemic areas, such as the city of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil (221, 222).