Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 has engendered a global health crisis along with diverse impacts on economy, society and environment. Efforts to combat this pandemic have also significantly shot-up the quantity of Bio-medical Waste (BMW) generation. Safe disposal of large quantity of BMW has been gradually posing a major challenge. BMW management is mostly implemented at municipal level following regulatory guidelines defined by respective states and the Union. This article is a narrative of the status of BMW generation, management and regulation in India in the context of COVID-19 crisis. The article is based on comparative analysis of data on BMW generation and management from authentic sources, a systematic literature review and review of news reports. In the current pandemic situation where media has been playing a significant role in highlighting all the concerns related to COVID-19 spread and management. Assessing the ground situation regarding effectiveness of prevailing BMW management facilities, requirement and suggestions can provide insights to the subject with policy implications for India and countries as well. The discussion has been built on different dimensions of BMW management during the pandemic including existing infrastructures, capacity utilisation, policy guidelines, operational practices and waste-handlers aspects. The results on state-wise analysis of reported BMW quantity and active COVID-19 patients also reveal some non-linear relationship between the two variables. Delhi, the National Capital is situated at a better position in terms of BMW management as compared to other studied states. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights to the policy makers and other relevant authorities to evaluate adequateness as well as efficiency quotients of entire BMW management landscape. Some of the critical observations of this article are also expected to offer impetus for enhancing national disaster preparedness in future.

Keywords: BMW, Healthcare waste, Safe disposal, Environmental health, Waste management regulations

BMW; Healthcare waste; Safe disposal; Environmental health; Waste management regulations

1. Introduction

Growing medical technologies and modern facilities in hospitals for providing better healthcare have contributed in subsequent increase in quantity of waste generated from health care facilities. The term “Health Care Waste” or “Bio-Medical Waste” includes all the wastes from any medical procedure in healthcare facilities, research centres and laboratories (WHO, 2017). The activities generating Bio-Medical Waste (BMW) may be in healthcare, research or diagnostic facilities with one or more of the activities such as diagnosis, treatment, immunization of human beings and animals and production or testing of biological materials. Biomedical waste also includes waste produced during any healthcare activities taken place at home. The types and characteristics of the contents determine how hazardous is the waste. The classification is based on presence of infectious substances, radioactivity, presence of sharps, genotoxic, cytotoxic, other toxic chemicals and biologically aggressive pharmaceuticals (WHO, 2017). Management of BMW in improper way result in several problems including spread of infectious diseases and different forms of environmental pollution (Rai et al., 2020). It has been established that 10–25% of BMW is dangerous (Rao and Ghosh, 2020) and that part of the waste possess physical, chemical, and/or microbiological risk to anybody exposed or is associated in handling, treatment, and disposal of waste. Report of the Special Rapporteur UN Human Rights Council focuses on the adverse effects that the unsound management and disposal of medical waste may have on the rights to life and recommending additional measures that relevant stakeholders can consider to make improvements in the safe and environmentally sound management and disposal of BMW (Human Rights Council-United Nations, 2011).

Apart from the health risks associated direct contact with BMW, risk of adverse impact on human health can also be associated due to exposure to emissions of highly toxic gases during incineration. Improper operation or deficiency in operation of the small- scale incinerators may result in incomplete waste destruction, inappropriate ash disposal and dioxins emission, which can 40000 times higher than emission limits set forth on Stockholm Convention (Batterman, 2004). In India, to deal with the problems associated with BMW, under the provision of Environment (Protection) Act 1986, Bio Medical Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 1998 was notified; these rules apply to all the persons who generate, collect, receive, store, transport, treat and handle or dispose BMW in any form. Later, it was revised (2016), thereafter amended (2018) to boost the segregation, transportation, and disposal for reducing environmental impact (BMWM Rules, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a global health crisis along with diverse impacts on environment, economy and society. It has posed various challenges to the existing regulations and management practices regarding BMW worldwide. Wuhan in China witnessed a rise of healthcare waste generation by 600% in the middle of COVID-19 outbreak (Jiajun, 2020). Restriction in recycling to prevent the spread of the virus, increase in generation and improper treatment have posed alarming situation (Zambrano-Monserrate et al., 2020). The management of BMW during this pandemic has been highlighted as major concern by several researchers (Wang et al., 2020; Boora et al., 2020; Gupta and Agrawal, 2020; Misra et al., 2020; Shammi et al., 2020), which can increase the risk of further contagion through different pathways.

As the increased generation of BMW is inevitable during COVID-19 outbreak, safe handling, treatment and disposal of waste must be prioritized for minimizing contamination of land, water and air. This paper has attempted to examine the existing situation of BMW in terms of its generation, handling and treatment during this current pandemic situation in India. It has also looked into the regulatory changes formulated at various levels to deal with adverse consequence of COVID-19 related BMW (BMW-COVID).

2. Methodology

The research is based on secondary data, a systematic literature review and review of news articles. A systematic investigation of all the scientific articles and reliable media articles available in web domain pertaining to the subject in the current context of COVID-19 pandemic has been done. Identification of issues regarding BMW-COVID and environmental and health impacts of its mis-management, status of reporting on collection and disposal etc. has been done with the help of review of recent literatures. Data on BMW generation, treatment and disposal across the states as well as data on COVID-19 positive cases have been collected from various government portals [Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), State Pollution Control Board (SPCB)s, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IITD)]. Detailed state-wise analysis is carried out at two levels, one for 13 States/Union Territories (UT)s and another for six states which are with relatively high impact of COVID-19. Number of total positive cases was considered for selection of states. Data synthesis and statistical analysis (descriptive analysis, correlation, multivariate regression) have been done in MS-Excel. Selected data has been used to develop maps using ArcGIS.

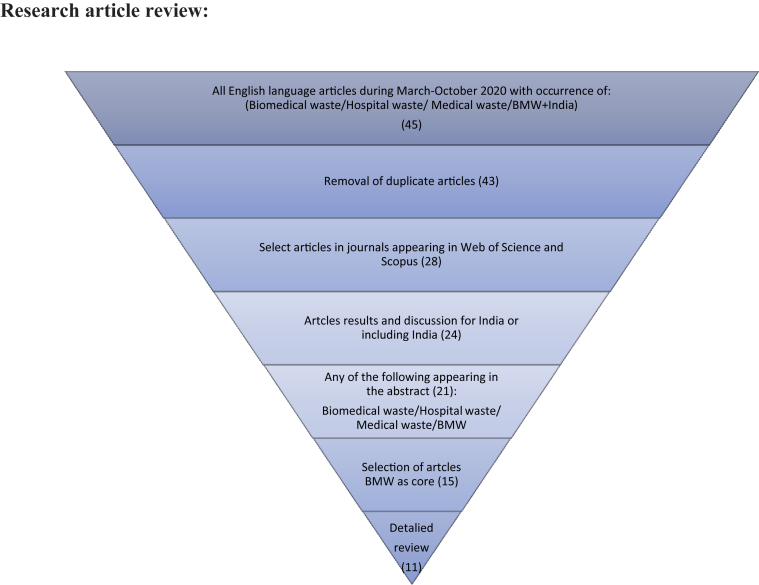

A systematic review of research articles has been done to document the on-going scientific discussion on COVID-19 related BMW (Yang et al., 2018; Mardani et al., 2019; Moher et al., 2015). The exploration of scientific articles is based on a few criteria viz.- time limit (March–October 2020), English language, combination of search terms (Biomedical waste/Hospital waste/Medical waste/BMW + India), presence in Web of Science and Scopus. Further refinement in the selection process has been done as presented in the Figure 1. Recent studies which were screened in the fourth level and didn't qualify for review mostly include mention about safe disposal of PPE, risk of contamination from waste mis-handling, hazards of BMW and biomedical waste management regulations (Panda et al., 2020; Tabish et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Bashir et al., 2020; Misra et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Criteria and selection process for BMW-COVID-19 literature pertaining to India for review.

There have been several methodologies for news review and content analysis, which have been evolved with the evolution of modern mass media (Duan and Takahashi, 2017; Media literature review guide: How to conduct a literature review of news sources, https://www.lib.sfu.ca/). Information from mass media can be very useful to evaluate emerging scientific ideas and concerns across geographical locations and over time (Antilla, 2010). Criteria-based compilation environmental news database shows that environmental information occupies certain columns and spaces in different media (Amiraslani and Caiserman, 2018). BMW-COVID-19 being a recent phenomenon creating emergency situations across the world, all latest developments regarding BMW have been covered uniformly by all the leading dailies in India; which has been established through a screening of all online news platforms including online editions of leading English dailies, web-based news portals and online versions of weekly, bi-monthly and monthly magazines. Other than considering circulation score, 10 expert opinions have been recorded to identify top five daily newspapers with online editions. The highest scored five newspapers have been selected for the review. The selected newspapers include The Hindu, The Times of India, The Hindustan Times, The Indian Express and The New Indian Express. News articles have been selected for review by using Google Search Engine (News) for March–August 2020, searching each month separately. Search phrases/terms used include COVID-19, BMW, Medical Waste India, Biomedical Waste, Hospital Waste and India, where COVID-19 and India were constant in all the searches with any of the other terms. For each of the search, first 50 news articles were screened and all the five selected newspaper articles were studied to extract the required information. All the listed relevant news articles have been distributed in five groups based on content of the articles.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Discussion on BMW-COVID-19 in scientific literature

The papers qualified for the review counted 11 and are presented in the Table 1. Among those studied, nine are review articles and two are based on analysis of secondary data (Kumar et al., 2020a; Sangkham, 2020). Three review articles have COVID-19 related BMW as their core focus (Ilyas et al., 2020; Ramteke and Sahu, 2020; Das et al., 2020) and the rest mostly discussed both positive and negative environmental consequences of COVID-19. In that holistic environmental discourse, BMW received position as the negative externality of the highest degree. The linkages of Biomedical waste management with other wastes, namely, municipal solid waste and more specifically food waste and plastic waste have been emphasized (Kulkarni and Anantharama, 2020; Sharma et al., 2020; Vanapalli et al., 2020). Mixing of waste, improper handling and safety measures, inadequate treatment facility, lack of mechanization and automation, increasing share of plastic wastes, risk of disease transmission and vulnerability of waste handling workers are some of the major concerns emerged from the studied literatures. Studies with implementable goal-oriented objectives leading to suggestions with policy implications, like the one by Kumar et al. (2020a) are need of the hour to deal with the massive problem of BMW management with many un-estimated health and environmental impact. In that study, life cycle assessment of PPE shows that decentralized incinerator is a better option for PPE waste management as compared to centralized facilities including both incinerator and landfill. It has been observed that there is insufficient studies on safety aspects of BMW management.

Table 1.

Brief description of reviewed articles on Biomedical Waste during COVID-19.

| Sl. No. | Author | Title | Focus area | Findings | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sharma et al. (2020) | Challenges, opportunities, and innovations for effective solid waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic | Biomedical, plastic and food waste management during COVID-19 | Contamination from virus-laden BMW and health risks of sanitation workers, increased plastic waste and food waste. Need of building resilience to face future catastrophe. | Review paper mostly based on general waste management literature |

| 2 | Kulkarni and Anantharama (2020) | Repercussions of COVID-19 pandemic on MSW management: Challenges and opportunities | Global overview of MSW management during COVID-19 outbreak. | Increased burden on MSW, mixing of BMW and risk of disease transmission through solid waste handling, impact of increasing BMW on MSW management system. | Review paper with evidences from current pandemic |

| 3 | Ilyas et al. (2020) | Disinfection technology and strategies for COVID-19 hospital and bio-medical waste management | Disinfection technologies for handling COVID-19 waste | Emergence of new type of BMW. A combined approach by environmental and medical researchers to adopt appropriate technique. | Review paper on waste management practices in a few COVID-19 affected countries. |

| 4 | Ramteke and Sahu (2020) | Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: considerations for the biomedical waste sector in India | Potential impact of COVID-19 on BMW administrations, focuses where option working methodology or extra moderation measures might be fitting. | Highlights the need for considerations for further measures towards BMW management | Review article mostly from disease transmission point of view and general implication in BMW sector |

| 5 | Das et al. (2020) | Biomedical Waste Management: The Challenge amidst COVID-19 Pandemic | Irrational use and disposal of PPE, mixing of BMW with other wastes and other ill-management practices | The indiscriminate disposal of BMWs in the general garbage posing risk to the susceptible community | Short article based on literature |

| 6 | Somani et al. (2020) | Indirect implications of COVID-19 towards sustainable environment: An investigation in Indian context | Effects of COVID-19 restrictions on the environment in India. Investigate the impact of COVID-19 on waste management. | Automation and mechanization of waste management system is required | Review article on environmental impact of COVID-19. Status of BMW generation and management capacity in India was discussed |

| 7 | Vanapalli et al. (2020) | Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic | Plastic waste management during pandemic | Proper segregation and safety measures for plastic waste in BMW. Contaminated BMW should not be part of MSW | Review article in general for plastic waste and discussion on precautions for plastic waste as part of BMW |

| 8 | Kumar et al. (2020a) | COVID-19 Creating another problem? Sustainable solution for PPE disposal through LCA approach | Life Cycle Assessment of PPE kits under two disposal scenarios, namely landfill and incineration (both centralized and decentralized) for six environmental impact categories | Disposal of coverall has the maximum impact, followed by gloves and goggles, in terms of GWP. The incineration process showed high GWP but significantly reduced impact w.r.t. other environmental and health impacts. High overall impact of landfill disposal compared to incineration. The decentralized incineration has emerged as environmentally sound option. | It is a comprehensive study to assess environmental impacts of PPE and findings have potential to contribute towards making policy decisions |

| 9 | Rume and Islam (2020) | Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability | Positive and negative environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Negative consequences of COVID-19, such as increase of medical waste, haphazard use and disposal of disinfectants, mask, and gloves | Review article on environmental impact of COVID-19, BMW is one of the components |

| 10 | Sangkham (2020) | Face mask and medical waste disposal during the novel COVID-19 pandemic in Asia | A rapid estimation of face mask and medical waste generation and environmental consequences related with the COVID-19 pandemic. | Discussion on reducing impacts of waste management through standardisation, procedures, guidelines and strict implementation of medical waste management related to COVID-19. | The study presents potential impacts of face masks estimated on the basis of secondary data. It gives an insight to the massive problem of waste management |

| 11 | Salve and Jungari (2020) | Sanitation workers at the frontline: work and vulnerability in response to COVID-19 | A study on socioeconomic status and vulnerability of Sanitation workers | Policy to safeguard sanitation workers by providing them adequate protective equipment, ensure regular and good payment and health insurance. | It is a short review article highlighting the vulnerability of sanitation workers |

3.2. Discussion on BMW-COVID-19 in mass media

A total of 74 newspaper articles have been reviewed to assess the types of information available in mass media on COVID-19 related BMW from March 2020 to August 2020 across different states of India. All documented news articles with relevant analysis parameters are in Annexure-1. When the news articles were grouped into five aspects of BMW management, it was observed that the group “monitoring, action and penalty” has the highest number of news articles, followed by regulation and notification (Annexure-2a). During initial days of the pandemic i.e. the month of March, the number of reports was the highest as compared to other studied months; where, emphasis was largely on regulatory guidelines and CPCB notifications for proper management of BMW. It also highlighted the inadequate infrastructure and resources for BMW management. Reporting on monitoring, management initiatives and penalty gradually increased with the spread of virus from May to August, when violations of BMWM Rules 2016 were apparently increasing. Mixing of BMW with household solid waste, deceased patients' beddings and other non-hazardous wastes from quarantine homes and COVID-care centres, which led to increased quantity of BMW and associated problems in treatment facilities were reported in 12 articles across the country. Figure 3 represents state-wise news reporting in the five leading dailies, where highest reporting has been observed in Maharashtra with 20 news articles covering all the five aspects of BMW management. Rest of the articles cover other 15 states/UTs of the country. Concerns regarding safe handling and health of waste workers have been reported in seven states.

Figure 3.

Change of active cases of COVID-19 in selected states/Union Territories high impacts of COVID-19.

3.3. COVID-19 cases and BMW management; a state-wise overview

Central Pollution Control Board Annual Report- 2018 (CPCB, 2018) mentions that 28 Indian states have arrangements for environmentally safe disposal of BMW. Those states have 200 authorized Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facilities (CBWTFs) and remaining seven states (Goa, Andaman Nicobar, Arunachal Pradesh, Lakshadweep, Mizoram, Nagaland and Sikkim) do not have CBWTFs. In addition to those facilities, there are 12,296 captive treatment and disposal facilities installed by Healthcare Facilities and authorised by concerned State Pollution Control Board/Pollution Control Committee (SPCB/PCC). As per CPCB Annual Report for the year 2018, the total number of healthcare facilities is 2,60,889, which is estimated to generate about 608 MT per day of BMW, out of which 528 MT is treated and disposed through either CBWTF or Captive disposal facility (CPCB, 2018). Results of a research in Pune city revealed 69.2% of the hospitals had a biomedical waste management facility (Kulkarni and Yeravdekar, 2020).

India's utmost effort in combating this pandemic have significantly shot-up the quantity of waste generated from healthcare facilities, quarantine facilities and laboratories etc. This manyfold increase in hospital waste generation is likely to exert pressure on the waste management system and may bring a situation of jeopardized environment and community health. Under conventional situations, India generates a much lower quantity (0.3–1kg/bed/day) of BMW as compared to Netherlands (2.7 1kg/bed/day), France (2.51kg/bed/day) and USA (4.51kg/bed/day) (CPCB, 2015). India's reported BMW generation per bed per day is even lower than other developing countries; for example, Bangladesh generates 1·63–1·99 kg per bed per day in Dhaka (Rahman et al., 2020). In Europe, Suez (a company engaged in treatment, disposal and energy recovery of BMW) has presented some estimates of increase in Biomedical waste generation during this pandemic. Their facilities in different locations with impacts of COVID-19 have observed momentous increase in the quantity received for treatment; Sausheim (Haut-Rhin) plant in Grand Est has an increase of 40%, a 50% rise in VALO'MARNE in Ile-de-France and a 30%–50% increase in Netherlands. The hospitals in Wuhan, China are generating six times more waste during the peak of COVID-19 outbreak than any normal day prior to the crisis (The Verge, 2020).

In Kerala, according to another media report, COVID-19 related BMW rose by more than 13000kg per day within a week (between 13–18 May, 2020), which is 2–2.5 Tonnes/day increase in quantity (Times of India, 22nd May 2020). The National Green Tribunal, Principal Bench Order of July 20, provide information that available capacity for incineration of COVID-19 biomedical waste in India is about 840 Metric Tons (MT). It is estimated that about 55% of cumulative incinerator capacity in the country is being utilised. However, there may be capacity limitation in specific areas or cities when the available capacity of CBWTFs in a coverage area of 150 km may not be adequate due to spike in generation of biomedical waste (NGT, 2020a).

Estimation of BMW generation in India varies 0.3kg–1kg BMW per bed per day and statements of medical practitioners reveal approximately 15 times increase in BMW in case of treating COVID-19 patient (Hindustan Times, 18th April, 2020), 4.5kg-15 kg of BMW production per COVID-19 patient per day is a rational figure to consider for the estimation in India. Calculation considering lower value can come close to the reported waste generated only in case of Delhi (4.1kg/day/patient as in Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimation of COVID-19 positive cases and pattern of BMW-COVID generation in selected states.

| State/UT | Number of COVID-19 cases | Percentage of infected to total population | BMW-COVID- 19 (tons in Aug 2020) | Assumed patients in Hospital∗ (1in 5 active) ∗∗ | Per capita BMW generation (kg/day) | No. of HCFs having Captive Treatment Facilities | No of Captive Incinerators Operated by HCFs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maharashtra | 1224000 | 1.07 | 1359 | 33400 | 1.36 | 218 | 4 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 630000 | 1.27 | 118.8 | 17868 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 |

| Tamilnadu | 547000 | 0.81 | 481 | 10732 | 1.49 | 0 | 0 |

| Karnataka | 526000 | 0.82 | 588 | 16344 | 1.20 | 2985 | 3 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 358000 | 0.18 | 408.8 | 9865 | 1.38 | 10 | 10 |

| Delhi | 250000 | 1.32 | 296.1 | 2402 | 4.11 | 3 | 0 |

∗Based on average daily active cases; ∗∗ WHO estimation.

Date Sources: CPCB, GoI; Census of India, GoI.

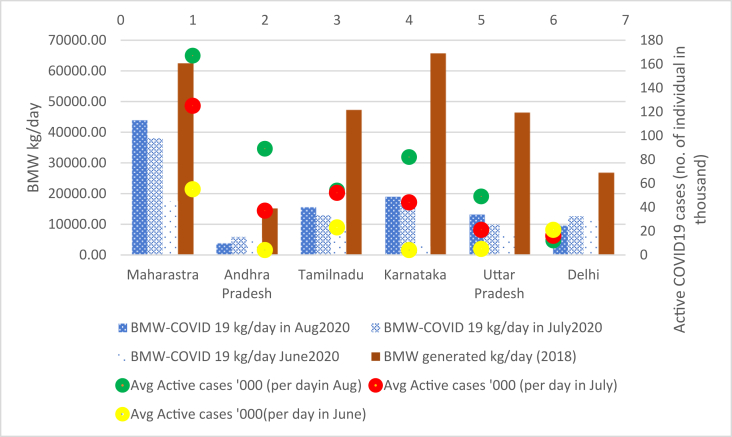

Average daily active patients and generation of BMW-COVID-19 (daily average) for three months (June–August) in top six affected states have been presented in Figure 2. Average daily BMW generation during 2018 is presented as three-dimensional bars in the figure. Karnataka and Maharashtra generate the highest amount of BMW in non-COVID-19 situations with 65 MT per day and 62 MT per day respectively. BMW-COVID-19 generation in these two states have reached approximately 44 MT per day in Maharashtra and 19MT in Karnataka. Maharashtra also tops the list of states with bedded healthcare facilities with 19,647 HCFs, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Karnataka. Increase in number of average daily active cases from the month of June to August varies from 2.34 to 22.25 times in top five states except Delhi where there was a decrease in number of cases over the three months. Andhra Pradesh exhibits the highest rise is active cases (22.25 times) with a decrease in BMW-COVID-19 generation (0.7 times change) from June to August. The changes in active case and corresponding BMW generation per day are comparable in case of Maharashtra, Delhi and Tamil Nadu.

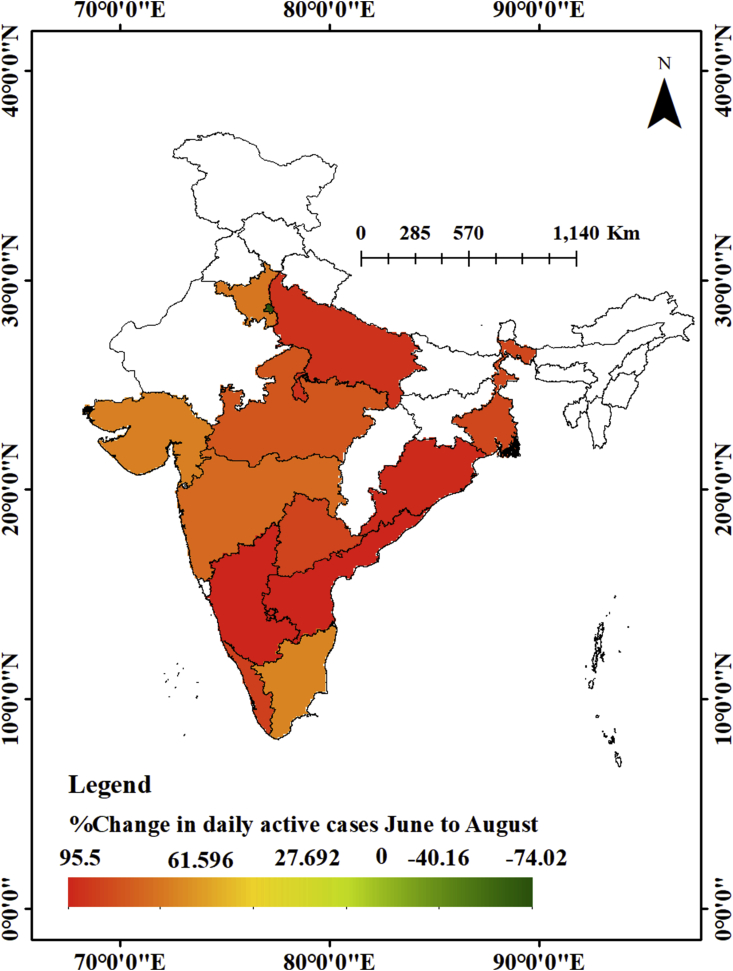

Figure 2.

Active COVID-19 patients, corresponding BMW-COVID-19 generated during June–Aug 2020 and business as usual BMW generation in top six affected states (Source: CPCB, 2018, NGT, 2020a)

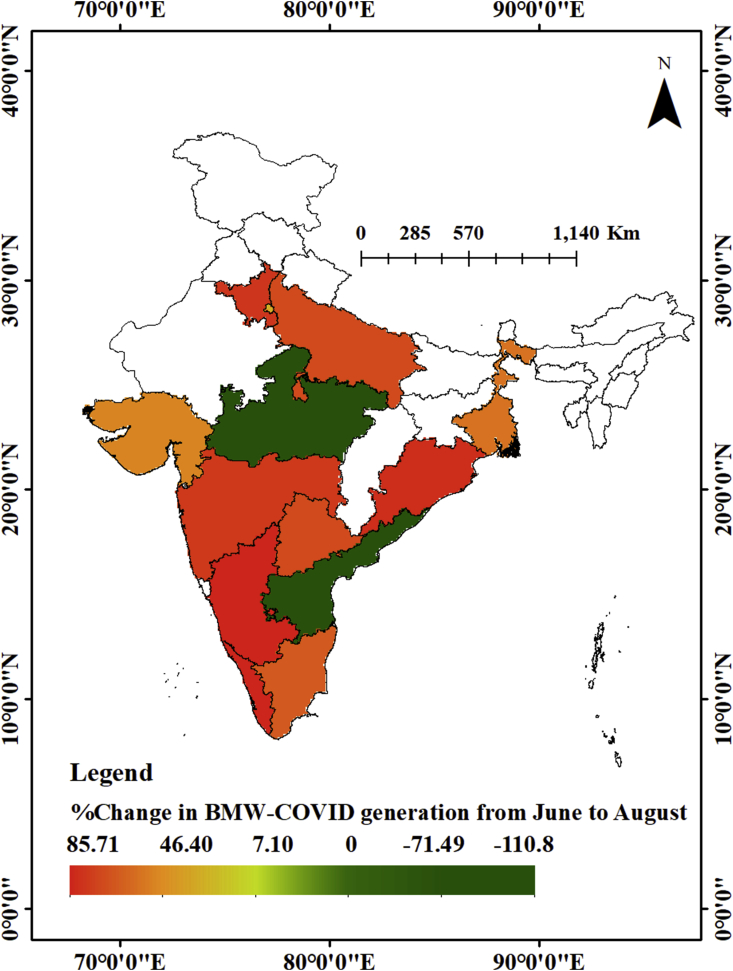

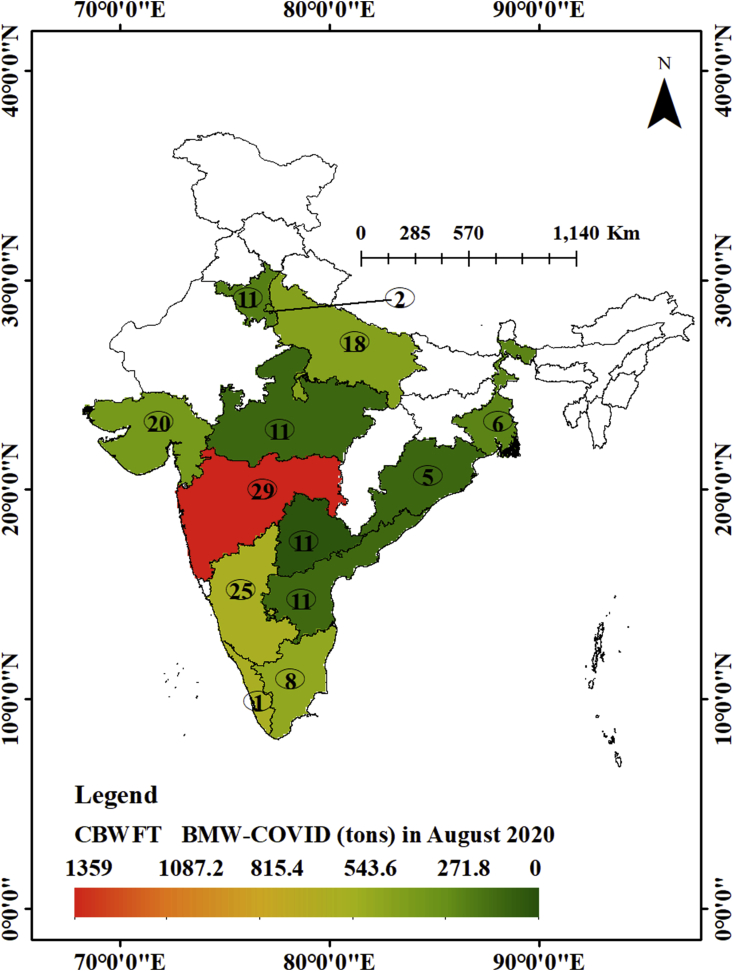

The percentage change in average daily active cases from June to August in 13 states/Union Territories are presented in Figure 3. Among the studied states/Union Territories, only Delhi has experienced a decrease in average daily active cases and the decline accounts 74% from June to August. However, the corresponding change in BMW-COVID quantity is just -12.6%. On the other hand, two states (Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh) have shown 75% and 95% increase in average daily active cases over the two months with whimsical decrease in BMW-COVID generation, i.e. 110% and 39% respectively (Figure 4). In non-COVID-19 situation, Karnataka is the largest producer of BMW followed by Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. The overall change in active COVID-19 cases and generation of COVID-19 related BMW has been studied for 13 states/UT of India which have been at the top in terms of total COVID-19 positive cases. These studied states/UT have 158 of total 198 CBWFTs of India (Figure 5). The increase in average daily active cases for 12 states of India has been observed over three months, viz.- June–August 2020.

Figure 4.

Change in generation of BMW-COVID in states/Union Territories high impacts of COVID-19.

Figure 5.

Generation of BMW-COVID and treatment facilities in states/Union Territories with high impacts of COVID-19 [Note: White pixels in all the above three maps (3–5ca) represent no data regions].

Maharashtra is the worst affected state due to the current pandemic, and in non-COVID-19 situation, it is among the top BMW generating states in India and with comparatively better management facilities. Annual report of Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) (2018–19) states that the state has 60,414 healthcare facilities, where 50,440 kg/day of BMW is generated from bedded hospitals, 11,793 kg/day is generated from non-bedded hospitals and 185 kg/day is generated from other sources. The state has 34 treatment facilities, out of which 29 have incinerators and five are deep burial facilities. There are three incinerator-based facilities within Bruhanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) to deal with BMW. Pollution Control Boards of specific states have also formulated and issued guidelines for Management of BMW with specific instructions for implementation. It is also seen that quantity has gone down in some days during that period, which is dubious in reality looking at the increasing number of active patients in the city. Officials attribute such discrepancies to improper segregation of waste at the source.

Among the six states (Table 2) the percentage of population reported as infected with COVID-19 varies from 0.18 (Uttar Pradesh) to 1.32 (Delhi) till August 2020. Estimation of patients in hospitals have been done as per WHO report (WHO, 2020a) that one in five COVID-19 patients worldwide is to be given medical care in hospital. The quantity of BMW-COVID thus calculated has shown 4.11kg per patient per day in Delhi; whereas, the same is remarkably low (0.22–1.49 kg per day per patient) for other five states. Among all six states/UTs, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu don't have any healthcare facility with captive treatment or incinerator facility. In such case, reports of low generation of BMW-COVID indicates mis-management of hospital wastes. Considering number of active cases across the states as the explanatory variable, a bivariate regression analysis has been done and the results are presented in Table 3. The analysis reveals that in the month of July (2020), the correlation between number of active cases and quantity of BMW-COVID has the highest R value (0.909) as compared to the preceding and proceeding months. Looking at the changing pattern of strengths of the correlation over the three months, it may be rational to assume that collection and reporting improved from June to July. The result is suggestive of situations where either COVID-19 related hospital waste was done in proper manner or there was a drastic decline in need of hospitalization for active patients in the month of August, even after a sharp rise in active cases from June to August.

Table 3.

Summary of regression analysis (Confidence level 95%).

| Variables | June 2020 | July 2020 | Aug 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | 0.815 | 0.909 | 0.77 |

| Standard Error | 88.54 | 130.80 | 232.54 |

| Significance F | 0.0007 | 1.69E-05 | 0.0021 |

| Intercept | 120.99 | 85.91 | 116.26 |

| X Variable 1 | 0.008 | 0.0083 | 0.0059 |

Waste producers' behaviour, segregation of waste, human resource capacities (staff and authorities), a well-established transportation system with treatment and disposal infrastructures, and monitoring functions are some of the factors influencing management of waste (Amitha and Manoj, 2020; Di Foggia and Beccarello, 2020; Datta et al., 2018). BMW in India is basically handled by third party organizations linked to municipalities. Capacities and compliance of those organizations play a major role in safe management of BMW (Rahman et al., 2020). Healthcare facilities with registration, legal recognition and linkage to third party waste management companies can be important determinants in adequate collection and reporting of actual BMW generated. Non-compliance of regulatory norms by healthcare facilities is highly prevalent in non-COVID-19 situation in India; where, only in 2018, State Pollution Control Boards and Committees have recorded 27427 HCFs or CBWTFs violating BMWM Rules, 2016 (MoHFW, 2020). Government data shows that India has more than 2 million hospital beds in 97382 hospitals. There are 68467 HCFs are running without authorization in the country. In addition to it, inadequate capacity of the existing facilities is likely to contribute to this intricate situation of BMW-COVID management. Report dated 17th June (NGT, 2020b) revealed that in the month of May (2020), most of the states (to name- Assam, Bihar, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Orissa, Rajasthan, Goa) didn't have adequate capacity to treat the growing quantity of BMW, where 70–90% of the states' CBWFT- capacity was utilized. A positive aspect reported was adequacy of treatment facilities in some of the highly affected states, viz.- Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh.

3.4. Interventions of regulatory authorities in BMW-COVID-19 management

Considering the magnitude of problem associated with BMW management during pandemic, Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has initially formulated guidelines (Guidelines for Handling, Treatment and Disposal of Waste Generated during Treatment/Diagnosis/Quarantine of COVID-19 Patients) based on current knowledge on COVID-19 and from other contagious diseases like HIV, H1N1 etc, and existing practices in managing infectious and hazardous wastes. CPCB has been issuing specific guidelines about segregation, collection, storing, transportation and disposal of BMW generating from the COVID-19 treatment facilities. The guidelines further stipulated that the Common Bio-Medical Waste Treatment Facilities (CBWTF) operators “shall ensure regular sanitisation of workers involved in handling and collection of biomedical waste and that they should be provided with adequate personal protective equipment”. PPE has been suggested as mandatory for all medical personnel with probable exposure to the virus including ambulance staff, persons involved in handling of any material exposed to COVID-19 care facilities.

Four revisions of the guidelines have been done to incorporate specific needs and tasks to be followed. First two revised guidelines specifically provide instructions on

-

•

Duties and responsibilities of persons of State Pollution Control Boards, Pollution Control Committees, Urban Local Bodies and persons involved in handling of wastes in Common Biomedical Waste Treatment Facilities and persons operating sewage treatment plants at healthcare facilities

-

•

Segregation of waste at the point of generation

-

•

Management of general waste from quarantine facilities

National Green Tribunal, India, expressed the need for further revision of the guidelines so that all aspects of scientific disposal of liquid and solid waste management are taken care of not only at institution level but also at individual levels, such as manner of disposal of used Personal Protection Equipment (PPE), without the same getting mixed with other municipal solid waste causing contamination. Administrations and the management of the service providers are required to provide adequate PPEs for the human resources handling BMW as prescribed in the guidelines. Training of the staff on proper provided disposal of waste material arising from COVID-19 care facilities is another key precautionary measure to be conducted to prevent exposure risks to contaminated substances.

Subsequent revisions (CPCB, 2020a) of the Guidelines incorporated guidance on

-

•

Segregation of general solid waste and BMW

-

•

Safety of waste handlers and sanitation workers

-

•

Providing training to waste handlers about infection prevention measures

-

•

Electronic tracking of BMW through an App “COVID19BMW”

-

•

Disposal of used PPEs

Technology enabled monitoring and tracking of BMW from generation to safe disposal became essential for efficiency optimization. CPCB developed COVID-19 waste tracking software named “COVID19BMW”, which can track BMW at the time of generation, collection and disposal. This application was designed for waste generators, CBWTF Operators, State Pollution Control Boards/Pollution Control Committees and Urban Local Bodies. The average daily quantity of COVID-19 related BMW generation is about 169 MT in August 2020, as reported from the data collected through the APP (CPCB, 2020b).

3.5. Changing composition of BMW and disposal risks

Amid sudden influx of Corona-virus patients in various healthcare facilities across India, disposal of BMW-COVID is becoming a major challenge. With approximately five million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and one million active cases by mid-September, India has second largest number of Corona-virus infected individuals in the world. Immense environmental health consequences, may arise due to improper management of BMW; due to highly contagious nature of the Corona virus, it can lead to serious situation by amplifying the status of COVID-19 spread, if appropriate and adequate measures are not implemented in each stage of BMW management. During the fight against COVID-19, it is expected to increase the amount of BMW from healthcare centres, quarantine and testing facilities. The quantity of BMW related to coronavirus disease in the district has increased by 585% between April and June months, showed data compiled by Biotic (Hindustan Time, 30thJune 2020). Along with the normal constituents of BMW, in case of COVID-19 related treatment procedures also generate huge quantity of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), primarily consisting of gloves, masks, goggles, face shield, shoe cover and hazmat (coverall) suits, used by the frontline healthcare personnel. The discarded PPEs are to be collected in Yellow and Red bags as classified under the BMW guidelines and to be disposed with utmost care at Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facilities (CBWTFs). The yellow category waste also includes human and animal anatomical waste, placenta, foetus, soiled waste, pre-treated microbiological and biotechnological waste, pharmaceutical and cytotoxic waste; linen and mattresses (BMWM Rules, 2016). The prescribed disposal method of BMW including PPEs, is incineration or plasma pyrolysis or deep burial. As polymer polypropylene, polyethylene, PVC and PET are used in making the PPEs, if proper procedures are not followed, disposal procedure may lead to potential environmental risks. Plastics mixed with other materials lowers the recyclability and infected plastic waste may pose high risk of viral transmission to the people in the recycling job (Tenenbaum, 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). The National Green Tribunal (NGT), India, has urged the State Pollution Control Board and Pollution Control Committee to put in serious efforts to mitigate the possible risk of unscientific disposal of the BMW arising out of the handling of the COVID-19 disease.

Other important issue, which needs a careful consideration is the potential environmental impact of disposal of non-biodegradable BMW (PPEs and other equipment), as there is a huge spike in number of such items. A consolidated UN inter-agency demand forecast for PPEs suggested the needs for Low Income Countries (LICs) and Middle Income Countries (MICs) for the remainder of 2020 is 2.2 billion surgical masks, 1.1 billion gloves, 13 million goggles and 8.8 million face shields. Based on simulation exercises on the use of PPE during previous outbreaks with similar transmission modes, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), WHO recommends the need of 25 units of gown, 25 units of medical masks, 50 units of gloves, 1 unit each of N95 mask and face-shield each day per patient (UNICEF, 2020). Based on WHO modelling, an estimated 89 million medical masks, 76 million examination gloves and 1.6 million goggles per month would be needed globally. WHO estimates that PPE production needs to be increased by 40% to meet the global demand (WHO, 2020b).

According to market assessment report the demand for Polypropylene (PP) in India grew at a CAGR of around 8.51% during 2015–2019 period. As a response to the pandemic outbreak and call by WHO (WHO, 2020b), there has been a surge in manufacturing of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), demand for polypropylene gained and expected to grow further in coming years (Businesswire, 2020). By mid-May according to media report, around 600 companies started manufacturing about 450000 PPE suits per day, which is mostly contributed by textile sector manufacturing units (NDTV, 2020; Mezzadri and Ruwanpura, 2020).

As incineration is the most preferred choice of disposal of CBWTF in India because of its potential for pathogen destruction and volume reduction; but it will be prudent to keep in mind the potential spike of emission of hazardous elements from the incinerators. Incomplete burning in incinerator operation can result in production of dioxins, which are unintentional by-products of waste combustion. Dioxins, a group of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are referred to the family of structurally and chemically related polychlorinated dibenzo para dioxins (PCDDs), polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs) and certain dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) with similar toxic properties (WHO, 2016). Risk of adverse impact on human health like reproductive and developmental problems, can also be associated due to exposure to emissions of highly toxic gases. Chronic exposure to dioxin can also lead to damage to the immune system, endocrine mechanisms, nervous system and they are known carcinogens (WHO, 2017; Rai et al., 2020; Rao and Ghosh, 2020; Vilavert et al., 2015). Due to the chemical stability of dioxins, these toxins can stay longer in the body and have the ability to be accumulated in fatty tissues. The estimated half-life of dioxin is 7–11 years (WHO, 2016). Burning of medical devices made up of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is the largest dioxin producers in the environment (Mattiello et al., 2013). In addition, medical waste with metal component can act as a catalyst for dioxin formation. Standards for dioxin and furan emission from incinerators have been modified in the amended BMWM Rules, 2016. Standard for dioxin and furans has been set at 0.1 ng TEQ per cubic meter. Another pollution associated with incineration is disposal of bottom ash which are enriched with heavy metals and other toxics (Vivek et al., 2019). Indian scientists have proposed a strategy to dispose the PPE kits (nonwoven polypropylene) by converting to liquid fuel by catalytic pyrolysis method (Jain et al., 2020).

3.6. Capacity building of sanitation workers

Similar to the frontline warriors like doctors and nurses in the healthcare setup, sanitation workers are equally important group of stakeholders engaged effective management of COVID-19 pandemic. According to a study conducted by Dalberg Advisors (2017), there are estimated to be 5 million sanitation workers in India, where 50% of them are women. These workers are considered to be among one of the most vulnerable and marginalized communities in the socio-economic ladder.

One of the major concerns is lack of awareness about the hazards of biomedical waste among people exposed to or handling the waste at various levels. Awareness generation and training of the human resources dealing with collection and disposal of BMW are the key areas for ensuring safety and minimizing risks. Studies show that non-technical hospital staff and undergraduate medical students do not have adequate knowledge on BMW management (Pandey et al., 2020; Choudhary et al., 2020). A study in Pakistan during the current pandemic shows that less than half of the healthcare workers are aware about safe disposal of hospital waste such as personal protective measures (Kumar et al., 2020b). CPCB guidelines on COVID-19 related BMW management, instructed various authorities to provide training to waste handlers on infection prevention measures, hand hygiene, respiratory etiquettes, social distancing, use of PPE etc. CPCB also created audio-visual awareness generating material for relevant stakeholders (CPCB, 2020).

4. Discussion

It is encouraging to witness that the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has been in the forefront to come up with timely guidelines towards BMW-COVID-19. There are apparent challenges and gaps in implementing the guidelines due to inadequate infrastructure across the states and inconsistent operational efficiency of implementing agencies. Though there have been many revisions in regulatory guidelines for better management of BMW during this pandemic, no significant improvement of management efficiency has been observed over the study period. Weak monitoring system and low accountability are to be rectified through a strong penalty-based monitoring at each level. In spite of regulations in place for segregation of healthcare waste for safe disposal, mixing with municipal solid waste and other plastic waste is a major challenge in BMW-COVID-19 management in India (Sharma et al., 2020; Kulkarni and Anantharama, 2020). The gap between policy and implementation, more specifically pertaining to infrastructure, capacity and monitoring to be bridged. Strategies are essential to collaborate with private and public sector entities for innovation and technology integration to overhaul these manifested breaches. Considering the quantity of waste generated, technology for recycling and resource recovery should be given priority.

Incinerators, shredder, sharp pit, encapsulation, deep burial and chemical disinfection, which are obligatory for BMW management were found non-existing in 60%–90% of hospitals. Study in four states (West Bengal, Bihar Uttarakhand and Jharkhand) of India shows that 72% of hospital wastes are not segregated and 74% of the hospitals are not connected to any CBWTF (WHO, 2017). Though most of the hospitals are tied to a centralized waste management facility, open dumping is still prevalent in the country, which is either by the healthcare facility or by the treatment facility while on the roadside while transporting the waste. High prevalence of open dumping (56%) and irregular collection by CBWTF vehicles, low level of staff awareness etc. are some of the major lacuna that affecting hospital waste management (WHO, 2017). Pollution Control Committees (SPCBs/PCCs) for the year 2018, about 27427 instances of violations under Bio-Medical Waste Management Rules, 2016 were reported against Healthcare Facilities (HCFs) or Common Biomedical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facilities (CBWTFs). Another report (ASSOCHAM-Velocity MR report, 2018) revealed that in India, the major challenges pertaining to BMW management are under-reporting of waste generated and handling capacities, operation of healthcare facility without authorization, lack of awareness among the people involved in handling of BMW at different levels. Study in Bhutan during this pandemic has also identified lack of healthcare workers capacity and weak implementation of National guidelines as major shortcomings in proper management of BMW (Zimba Letho et al., 2021). Another study in Saudi Arabia revealed that the healthcare workers are well-aware of the safety precautions to be taken but have low level of knowledge about waste management procedure in their healthcare facilities (Aleanizy and Alqahtani 2020).

There are several loopholes in the existing system of BMW management in the country which might have posed grievous toiling situation in BMW-COVID-19 management. Lack of awareness, strong need of training for technical and non-technical staff, improper segregation etc. are some of the concerns to be addressed for enhancing efficient implementation (Pandey et al., 2020; Krishna et al., 2018; Archana et al., 2016; Goyal et al., 2017; Soyam et al., 2017; Sudeep et al., 2017). This shortcoming may be attributed to inadequate functioning of institutional and financial mechanisms for surveillance, monitoring, incentives and penalty. CAG report (Comptroller and Auditor General of India GoI, 2017) on BMW in Maharashtra emphasized the need of implementation of the Rules with adequate administrative and regulatory framework. The non-compliances and initiatives for BMWM are in a bi-directional impact loop; specifically, functioning of healthcare establishments without authorization amplify the threats, which certainly alienate significant quantity of BMW unaccounted further resulting in discrepancies in planning. Costs for safe treatment and disposal of hazardous health-care waste are typically more than ten times higher than those for general waste in non-pandemic situation (WHO, 2018); whereas is India, it has been identified that shortage of fund is the prime problem in implementing BMWM efficiently (Datta et al., 2018). This cost estimation might have increased considerably when it comes to managing COVID-19 related BMW.

It is evident from the above results and analysis that there are existing gaps in infrastructure, capacity, monitoring, disposal and awareness levels required for effective management of BMW in India. Not all states have adequate facilities and resources to manage BMW as prescribed by the authorities. Some of the states like Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat and Delhi have comparatively better BMW management infrastructure than the other states. Observations show manifold increase in domestic consumption of PPE and this trend is expected to continue. Media reports have been affirming the intricacies regarding management of increased quantity of BMW across the globe. The authorities need to adopt innovative strategies to manage plastic waste generated due to this pandemic and in this regard, the collaboration with scientific community will be paramount. It is revealed in both the reviews, scientific literature and media articles, that there is a critical need for emphasis on capacity building of the BMW handlers with proper training and providing them with modern equipment for safe and effective management of hazardous waste.

5. Conclusion

This article provides an overall position of India in management of BMW during the outbreak of COVID-19. There is a need to evaluate the entire BMW management infrastructure and necessary investments have to be made for expansion to improve the capacity and coverage. Such expenditure will worth its value and will ensure safe and sound BMW management with adequate capacity to get the country prepared for any future disaster. Stringent monitoring mechanism, operational and functional efficiency of CBWTFs and transparency aspects are other important elements, where constant focus from the relevant authorities is required to ensure safe and proper disposal of the BMW. More emphasis on innovation of environment-friendly technologies and capacity building of healthcare workers and waste-handlers are other concerns to be prioritized for safe collection, treatment and disposal of BMW. The experience of BMW management in this global crisis can be a learning for authorities to develop a well-equipped system for safe disposal in post-COVID-19 scenario and to provide insights for disaster preparedness in future.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Sunil Nautiyal, Mrinalini Goswami, Pranjal J. Goswami and Satya Prakash: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks to Dr. HUU HAO NGO, Associate Editor – Environment, Heliyon and four anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions, thought providing insights and constructive comments to improve the paper. This has helped the authors to revised paper and improved overall scientific outcomes of this interesting study on contemporary issue in India. We are thankful to the Director, Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC), Bengaluru for support and facilities. Views expressed here are of the authors only and not of the organization with which they are affiliated.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Aleanizy F.S., Alqahtani F.Y. 2020. Healthcare Workers Awareness and Knowledge of Covid-19 Infection Control Precautions and Waste Management: Saudi Arabia Cross Sectional Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiraslani F., Caiserman A. From air pollution to airing pollution news: multi-layer analysis of the representation of environmental news in Iranian newspapers. J. Int. Commun. 2018;24(2):262–282. [Google Scholar]

- Amitha A.J., Manoj V. Sustainable Waste Management: Policies and Case Studies. Springer; Singapore: 2020. Evidence-based analysis of patterns of challenges in solid waste management by Urban local Bodies in India; pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Antilla L. Self-censorship and science: a geographical review of media coverage of climate tipping points. Publ. Understand. Sci. 2010;19(2):240–256. [Google Scholar]

- Archana B.R., Gupta V., SreeHarsha S. Awareness of biomedical waste management among health care personnel in Bangalore, Karnataka. Indian J. Publ. Health Res. Dev. 2016;7(3):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Assocham-Velocity MR Report . Assocham; India: 2018. Unearthing the Growth Curve and Necessities of Bio Medical Waste Management in India. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B.J., Bilal K.B., Bashir M.A., Farooq T.H., Iqbal N., Bashir M. Correlation between environmental pollution indicators and COVID-19 pandemic: a brief study in Californian context. Environ. Res. 2020;187:109652. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterman S. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. Assessment of Small-Scale Incinerators for Health-Care Waste. 21 January. [Google Scholar]

- Bio-Medical Waste Management Rules National accreditation board for hospitals and healthcare providers. 2016. http://nabh.co/Announcement/BMW_Rules_2016.pdf [online]

- Bio-Medical Waste Management (Amendment) Rules. 2018. https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1526326 [Google Scholar]

- Boora S., Gulia S.K., Kausar M., Tadia V.K., Choudhary A.H., Lathwal A. Role of hospital administration department in managing Covid-19 pandemic in India. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2020;8(5) [Google Scholar]

- Businesswire . 3rd June 2020. India Polypropylene Market Assessment 2015-2030 - Tremendous Growth Opportunities in the Manufacturing of PPE - ResearchAndMarkets.Com.https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200603005330/en/India-Polypropylene-Market-Assessment-2015-2030---Tremendous [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary M., Verma M., Ghosh S., Dhillon J.K. Assessment of knowledge and awareness about biomedical waste management among health care personnel in a tertiary care dental facility in Delhi. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020;31(1):26. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_528_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comptroller and Auditor General of India, GoI . Government of Maharashtra; 2017. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (Civil) for the Year 2016.https://cag.gov.in/content/report-no5-2017-local-bodies-government-maharashtra [Google Scholar]

- CPCB . Central Pollution Control Board. Government of India; 2020. Guidelines for Handling, Treatment, and Disposal of Waste Generated during Treatment/Diagnosis/Quarantine of COVID-19 Patients - Rev. 4.https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/Projects/Bio-Medical-Waste/BMW-GUIDELINES-COVID_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CPCB . Central Pollution Control Board; 2020. Report on COVID-19 Waste Management.https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/Projects/Bio-Medical-Waste/COVID19_Waste_Management_status_August2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- CPCB . Ministry of Environment & Forests; GOI: 2015. Annual Report 2014-15. Central Pollution Control Board. [Google Scholar]

- CPCB . Ministry of Environment & Forests; GOI: 2018. Annual Report 2017-18. Central Pollution Control Board. [Google Scholar]

- Dalberg Advisor . 2017. Sanitation Worker Safety and Livelihoods in India: A Blueprint for Action.https://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/3-3483-7-1542726162.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Garg R., Ojha B., Banerjee T. Biomedical waste management: the challenge amidst COVID-19 pandemic. J. Lab. Phys. 2020;12(2):161. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta P., Mohi G.K., Chander J. Biomedical waste management in India: critical appraisal. J. Lab. Phys. 2018;10(1):6. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_89_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Foggia G., Beccarello M. Drivers of municipal solid waste management cost based on cost models inherent to sorted and unsorted waste. Waste Manag. 2020;114:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2020.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan R., Takahashi B. The two-way flow of news: a comparative study of American and Chinese newspaper coverage of Beijing’s air pollution. Int. Commun. Gaz. 2017;79(1):83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K.C., Goyal S.N., Goyal R. Analysis of bio-medical waste management in private hospital at Patiala State of Punjab, India. Octa J. Environ. Res. 2017;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Agrawal H. It will Be a different world for surgeons post-COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J. Surg. 2020:1. doi: 10.1007/s12262-020-02392-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindustan Times . 18th April 2020. 10% of Gurugram’s Biomedical Garbage Is Related to Covid-19.https://www.hindustantimes.com/gurugram/covid-19-waste-accounts-for-10-of-gurugram-s-biomedical-refuse/story-Zf4FZR0UuPM8MIwrlPBvdP.html [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Council, United Nations . Calin Georgescu; 2011. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Adverse Effects of the Movement and Dumping of Toxic and Dangerous Products and Wastes on the Enjoyment of Human Rights.https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/1683/A-HRC-18-31_en.pdf 18th Session, 4th July. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas S., Srivastava R.R., Kim H. Disinfection technology and strategies for COVID-19 hospital and bio-medical waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;749:141652. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Bhawna Y.L., Kumar S., Singh D. Strategy for repurposing of disposed PPE kits by production of biofuel: pressing priority amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Biofuels. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Jiajun W. 2020. Cement Industry in China Assisted with Disposal of Covid-19 Healthcare Waste.https://www.zkg.de/en/artikel/zkg_Cement_industry_in_China_assisted_with_disposal_of_Covid-19_healthcare_3535100.html [Google Scholar]

- Krishna C., Nisar J., Iyengar K., Das S.R. Awareness about biomedical waste management among hospital staff in a tertiary care hospital in Tumkur. Indian J. Prev. Med. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni B.N., Anantharama V. Repercussions of COVID-19 pandemic on municipal solid waste management: challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743:140693. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Katto M.S., Siddiqui A.A., Sahito B., Jamil M., Rasheed N., Ali M. Knowledge, attitude, and practices of healthcare workers regarding the use of face mask to limit the spread of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Cureus. 2020;12(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Azad A., Gupta A. COVID-19 Creating another problem? Sustainable solution for PPE disposal through LCA approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-01033-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardani A., Streimikiene D., Cavallaro F., Loganathan N., Khoshnoudi M. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and economic growth: A systematic review of two decades of research from 1995 to 2017. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;649:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiello A., Chiodini P., Bianco E., Forgione N., Flammia I., Gallo C. Health effects associated with the disposal of solid waste in landfills and incinerators in populations living in surrounding areas: a systematic review. Int. J. Publ. Health. 2013;58:725–735. doi: 10.1007/s00038-013-0496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzadri A., Ruwanpura K. 2020. How Asia’s Clothing Factories Switched to Making PPE–But Sweatshop Problems Live on. The Conversation UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Home and Family Welfare . 2020. Press Note released on 07 FEB 2020 12:49PM by PIB Delhi.https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1602353 [Google Scholar]

- Misra V., Bhardwaj A., Bhardwaj S., Misra S. Novel COVID-19–Origin, emerging challenges, recent trends, transmission routes and Control-A review. J. Contemp. Orthod. 2020;4(1):55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGT . 2020. BEFORE THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL PRINCIPAL BENCH, NEW DELHI. In reply to: Scientific Disposal of Bio-Medical Waste arising out of Covid-19 treatment- Compliance of BMW Rules 2016.https://greentribunal.gov.in/gen_pdf_test.php?filepath=L25ndF9kb2N1bWVudHMvbmd0L2Nhc2Vkb2Mvb3JkZXJzL0RFTEhJLzIwMjAtMDctMjAvY291cnRzLzEvZGFpbHkvMTU5NTMxOTc1NjEyNjg2OTQ2ODc1ZjE2YTVjY2JjMDM5LnBkZg== [Google Scholar]

- NGT . 2020. BEFORE THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL PRINCIPAL BENCH. Report on Scientific Disposal of Bio-Medical Waste arising out of Covid-19 treatment- Compliance of BMW Rules 2016.https://greentribunal.gov.in/sites/default/files/news_updates/Status%20Report%20in%20O.A%20No.%2072%20of%202020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- NDTV. 19th May 2020. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/from-zero-india-now-manufactures-4-5-lakh-ppe-suits-a-day-to-fight-coronavirus-2231742https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/from-zero-india-now-manufactures-4-5-lakh-ppe-suits-a-day-to-fight-coronavirus-2231742 [Google Scholar]

- Panda R., Kundra P., Saigal S., Hirolli D., Padhihari P. COVID-19 mask: a modified anatomical face mask. Indian J. Anaesth. 2020;64(14):144. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_396_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Pandey A.S., Sharma P. Revised biomedical waste management guidelines, 2016- knowledge, attitude and practices among healthcare workers in various healthcare facilities of Central India. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2020;8(12) [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.M., Bodrud-Doza M., Griffiths M.D., Mamun M.A. Biomedical waste amid COVID-19: perspectives from Bangladesh. Lancet Global Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai A., Kothari R., Singh D.P. Waste Management: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. IGI Global; 2020. Assessment of available technologies for hospital waste management: a need for society; pp. 860–876. [Google Scholar]

- Ramteke S., Sahu B.L. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: considerations for the biomedical waste sector in India. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020:100029. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V.V., Ghosh S.K. Urban Mining and Sustainable Waste Management. Springer; Singapore: 2020. Sustainable bio medical waste management—case study in India; pp. 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rume T., Islam S.D.U. Environmental effects of COVID-19 pandemic and potential strategies of sustainability. Heliyon. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salve P.S., Jungari S. Sanitation workers at the frontline: work and vulnerability in response to COVID-19. Local Environ. 2020;25(8):627–630. [Google Scholar]

- Sangkham S. Face mask and medical waste disposal during the novel COVID-19 pandemic in asia. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020:100052. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammi M., Bodrud-Doza M., Islam A.R.M.T., Rahman M.M. COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic crisis and human stress in resource-limited settings: a case from Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H.B., Vanapalli K.R., Cheela V.S., Ranjan V.P., Jaglan A.K., Dubey B., Goel S., Bhattacharya J. Challenges, opportunities, and innovations for effective solid waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020;162:105052. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somani M., Srivastava A.N., Gummadivalli S.K., Sharma A. Indirect implications of COVID-19 towards sustainable environment: an investigation in Indian context. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020;11:100491. doi: 10.1016/j.biteb.2020.100491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyam G.C., Hiwarkar P.A., Kawalkar U.G., Soyam V.C., Gupta V.K. KAP study of bio-medical waste management among health care workers in Delhi. Int. J. Commun. Med. Publ. Health. 2017;4(9):3332–3337. [Google Scholar]

- Sudeep C.B., Joseph J., Chaitra T., Joselin J., Nithin P., Jose J. KAP study to assess biomedical waste management in a dental college in south India. World J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;6:1788–1794. [Google Scholar]

- Tabish M., Khatoon A., Alkahtani S., Alkahtane A., Alghamdi J., Ahmed S.A., Mir S.S., Albasher G., Almeer R., Al-Sultan N.K., Aljarba N.H. Approaches for prevention and environmental management of novel COVID-19. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10640-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum L. 2020. The Amount of Plastic Waste Is Surging Because of the Coronavirus Pandemic Forbes.https://www.forbes.com/sites/lauratenenbaum/2020/04/25/plastic-waste-during-the-time-of-covid-19/#7c4e661f7e48 [Google Scholar]

- The Verge . March 26th, 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Generating Tons of Medical Waste.https://www.theverge.com/2020/3/26/21194647/the-covid-19-pandemic-is-generating-tons-of-medical-waste [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. COVID-19 Impact Assessment and Outlook on Personal Protective Equipment.https//www.unicef.org/supply/stories/covid-19-impact-assessment-and-outlook-personal-protective-equipment#:∼:text=A%20consolidated%20UN%20inter%2Dagency,and%208.8%20million%20face%20shields [Google Scholar]

- Vanapalli K.R., Sharma H.B., Ranjan V.P., Samal B., Bhattacharya J., Dubey B.K., Goel S. Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;750:141514. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilavert L., Nadal M., Schuhmacher M., Domingo J.L. Two decades of environmental surveillance in the vicinity of a waste incinerator: human health risks associated with metals and PCDD/Fs. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015;69:241–253. doi: 10.1007/s00244-015-0168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivek J.M., Singh R., Sutar R.S., Asolekar S.R. Advances in Waste Management. Springer; Singapore: 2019. Characterization and disposal of ashes from biomedical waste incinerator; pp. 421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Shen J., Ye D., Yan X., Zhang Y., Yang W., Li X., Wang J., Zhang L., Pan L. Disinfection technology of hospital wastes and wastewater: suggestions for disinfection strategy during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. Environ. Pollut. 2020:114665. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2016. Dioxins and Their Effects on Human Health.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health#:∼:text=Short%2Dterm%20exposure%20of%20humans,endocrine%20system%20and%20reproductive%20functions [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2017. Report on Health-Care Waste Management (HCWM) Status in Countries of the South-East Asia Region (No. SEA-EH-593) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2018. Health-care Waste Fact sheet Updated February 2018, Media centre.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs253/en/ [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Media Statement: Knowing the Risks for COVID-19.https://www.who.int/indonesia/news/detail/08-03-2020-knowing-the-risk-for-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment Endangering Health Workers Worldwide.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.Y., Qian Z., Howard S.W., Vaughn M.G., Fan S.J., Liu K.K., Dong G.H. Global association between ambient air pollution and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2018;235:576–588. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.