Abstract

Through analysis of paired high-throughput DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq data, researchers quickly recognized that RNA-Seq can be used for more than just gene expression quantification. The alternative applications of RNA-Seq data are abundant, and we are particularly interested in its usefulness for detecting single-nucleotide variants, which arise from RNA editing, genomic variants and other RNA modifications. A stunning discovery made from RNA-Seq analyses is the unexpectedly high prevalence of RNA-editing events, many of which cannot be explained by known RNA-editing mechanisms. Over the past 6–7 years, substantial efforts have been made to maximize the potential of RNA-Seq data. In this review we describe the controversial history of mining RNA-editing events from RNA-Seq data and the corresponding development of methodologies to identify, predict, assess the quality of and catalog RNA-editing events as well as genomic variants.

Keywords: RNA editing, ADAR, SNP, SNV, RNA-Seq, non-canonical RNA editing

Introduction

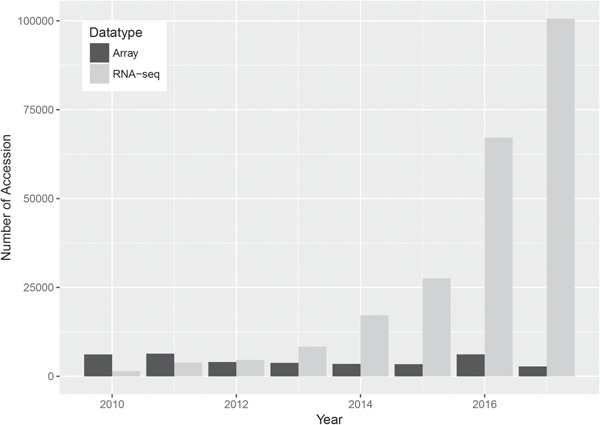

The two major High throughput Sequencing (HTS) paradigms are DNA and RNA sequencing, abbreviated as DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq, respectively [1, 2]. DNA-Seq, such as exome or whole-genome sequencing, has been used to characterize single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs) and structural variants including insertion–deletions (indels), translocations and inversions. RNA-Seq refers to the sequencing of the transcriptome and has been primarily used as a replacement for hybridization-based gene expression microarrays to quantify transcript abundance. Compared to microarrays, RNA-Seq bears several noticeable advantages, especially the ability to capture all expressed transcripts (rather than being limited to known genes with pre-designed probes) and to characterize the RNA sequence base by base. Thus, in theory, RNA-Seq data can be used to detect SNVs, which are a predominant part of clinically actionable variants in public knowledge bases. Due to the high popularity of RNA-Seq (Figure 1), huge amounts of RNA-Seq data have been accumulated and deposited in the public domain for future data mining.

Figure 1.

Data deposit comparison between RNA-Seq and microarray from 2010 to 2017 in Gene Expression Omnibus. The number of RNA-Seq data set steadily increased, while the number of microarray data set showed a decreasing tread. There is a small spike for microarray data set deposit in 2016. Upon further investigation, the majority of the microarray data sets deposited in 2016 were miRNA microarray data sets.

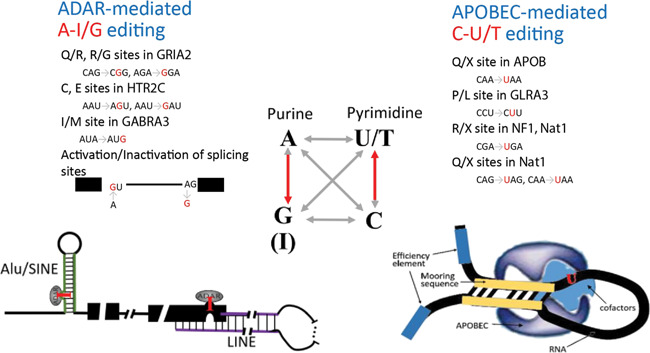

SNVs identified from RNA-Seq data can be divided into four major categories: RNA editing, genomic variants, other RNA modifications and sequencing errors. RNA editing creates a type of nucleotide variation of notable bio-medical significance [3]. By definition, RNA editing (Figure 2) describes processes of nucleotide alterations in RNA that post-transcriptionally change the genetic meaning encoded in the genome [4]. Genomic variants happen at the DNA level and some can be detected by RNA-Seq after transcription. Other RNA modifications such as m1A and m6A methylations may induce retrotranscription misincorporations, which are captured as SNVs by RNA-Seq. A portion of the SNVs identified by RNA-Seq may also be errors caused by imperfections in sequencing and bioinformatics approaches.

Figure 2.

Human RNA-editing events are composed of mainly A-to-I and C-to-U substitutions. The building blocks of DNA/RNA are adenine (A), thymine (T)/uracil (U), guanine (G) and cytosine (C). From DNA to RNA, 12 types of single-nucleotide substitutions may arise theoretically, whereas adenine-to-inosine (A→I/G, inosine is read as guanine in protein synthesis) and cytosine-to-uracil (C→U/T) are the 2 canonical types with characterized biological mechanisms. These two substitution types (red arrow) are both transitions. Mediated by ADAR enzymes, A-to-I RNA editing occurs in pre- or mature mRNAs and non-coding RNAs possessing imperfect double-strand motifs, such as Alu, SINE or LINE regions. C-to-U editing site is dependent on nearby cis-elements and multiple trans-factors coordinating with APOBEC. So far several tens of A-I/G and C-U/T editing events have been well resolved, a few of which are exemplified here with information on the affected genes and the specific amino acid codon changes. SINE, short interspersed nuclear element; LINE, long interspersed nuclear element; ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA; APOBEC, a family of cytidine deaminases or ‘apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzymes, catalytic polypeptide-like’.

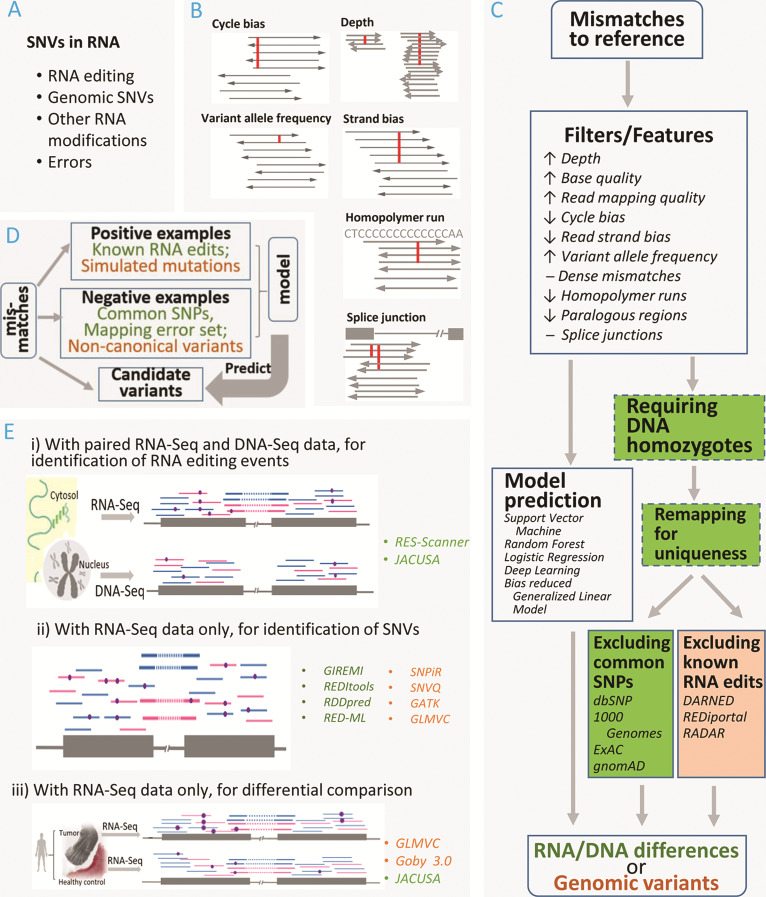

Most of the RNA-Seq data have been used only to study gene expression. Nonetheless, given the single-nucleotide resolution of RNA-Seq, some researchers have made significant efforts to identify SNVs from RNA-Seq data, including RNA-editing events and genomic variants (Figure 3A). Using this opportunity, we describe the historical aspect of how SNV detection evolved around the development of HTS.

Figure 3.

Identification of RNA edits or genomic SNVs from RNA-Seq data. (A) SNVs identified from RNA-Seq data can be divided into four major categories: RNA-editing events, genomic variants, SNVs originating from other RNA modifications and errors. Other RNA modifications such as m1A and m6A methylations may induce retrotranscription misincorporation, thus resulting in SNVs in RNA-Seq data. Errors are attributed to sequencing flaws, suboptimal alignment and random mistakes. (B) Factors that may be considered as indications of errors in SNV detection. Cycle bias: sequencers may have technical bias resulting in artifacts within close proximity to read ends. Depth: number of reads spanning the concerned variant. Variant allele frequency: fraction of reads carrying the variants. Strand bias: reads supporting the variant mostly map to one strand of the reference genome. Homolopolymer run: a tract of multiple identical nucleotides are more susceptible to false positives due to misalignment. Splice junction: variants close to intron-exon junctions are usually of lower confidence due to imprecise junction boundaries. (C) Common analysis modules assembled into generic pipelines for identifying RNA edits or genomic SNVs. A number of relevant factors positively (↑) or negatively (↓) associated with meaningful SNV identification are utilized as basic filters or are coded into features for model prediction. Dense mismatches and splice junctions have complex association with the findings. Dense mismatches may reflect low sequencing quality but may also signify RNA hyper-editing regions; exon-first mapping is generally recommended to reduce errors but this has been blamed for leading to erroneous preference of intronless pseudogenes over transcriptionally active genes. To rule out the suspicion on homology-led false positives, a realignment step is often practiced but not mandated. When DNA-Seq data are available, RNA editing events must be guaranteed with homozygote status of the counterpart DNA variants. Alternative to the stepwise filtration pipeline, machine learning approaches build the relevant factors into features and construct models to predict true variants. Green: detection of RNA editing. Orange: detection of genomic variants. (D) Scaffold of model prediction, typically involving machine learning approaches. For predicting RNA edits (green), previously known RNA edits form positive examples, while common SNPs or artificially planted mismatches (‘mapping error set’) are taken as negative examples. For predicting DNA variants (orange), a deep-learning approach (doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/079087) simulated somatic mutations for positive examples and identified non-canonical variants from raw variant set as negative examples. (E) Application of RNA-Seq in three scenarios to study SNVs in RNA. i) For identification of RNA-editing events, the most straightforward experimental design entails RNA-Seq and the coupled DNA-Seq for the same sample source. ii) Due to practical reasons, a surge of methods are developed to identify RNA-editing events or genomic variants from RNA-Seq data only. Some RNA editing methods handle optional input of DNA-Seq data. iii) RNA-Seq is conducted on multiple disparate samples with a primary focus of differential comparison. This scenario has been deployed for detection of somatic mutations or quantification of varied RNA-editing levels.

Historical reflection on HTS-assisted RNA-editing studies

In humans, RNA editing causes nucleotide substitutions in RNA as compared to the corresponding DNA sequence. Among the 12 possible types of RNA-editing substitutions, A➔I and C➔U are canonical RNA-editing events with well-characterized biological mechanisms (Figure 2). Aberration of A➔I editing mostly leads to neurological disorders [3], and malfunction of C➔U editing causes a variety of diseases, including atherosclerosis, myopathy and certain cancers [3]. RNA-editing events occur in both coding and non-coding RNAs, and they effectively increase the diversity of human transcriptome and induce a layer of swift regulation of mRNAs and non-coding RNAs at the post-transcriptional level.

In the early days, A-to-I RNA-editing events were primarily discovered in Alu elements of the human genome [5]. Alu is a type of nonautonomous retrotransposon of ∼300 bp in size, widely distributed across the human genome with over 1 million copies [6]. Inverted repeated Alu elements in a transcribed RNA induce the formation of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures, which are recognizable to adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) enzymes. ADAR enzymes make adenine-to-inosine (A-to-I) substitutions in imperfect dsRNA motifs commonly seen in Alu and other short or long interspersed nuclear elements (Figure 2). In humans, A-to-I substitutions are found as the dominant RNA-editing events, much more prevalent than the other canonical C➔U events [7]. Before the wide application of HTS, sporadic reports accumulated only a few dozen RNA-editing events outside repetitive regions in humans, predominantly A➔I or C➔U events [3].

The earliest HTS-assisted endeavors to describe human RNA-editing events were accomplished through targeted RNA-Seq in 2009 [8, 9]. These studies were limited by the HTS and bioinformatics methodology at the time. The very first high-throughput catalog of human RNA editing appeared in Science in 2011 [10]. In that study, Li et al. claimed to observe widespread RNA editing by comparing paired RNA-Seq to exome sequencing data from 27 individuals. This study found 10 210 exonic RNA-editing events, including 6698 A➔I, 1220 C➔U and 2292 other (non-canonical) RNA-editing events.

Li et al.’s report immediately initiated an intense and prolonged debate focusing on the magnitude of human RNA-editing events and the bioinformatics approaches. Three comments [11–13] were published in Science the following year questioning the conclusion by Li et al. All three comments had the common theme that a large portion of the RNA-editing events identified by Li et al. represented merely technical artifacts such as sequencing or alignment errors. In all three comments, the authors focused on sequencing cycle bias, which introduces more errors at either the beginning or the end of reads (Figure 3B). Cycle bias is ubiquitous with Illumina HTS technology and is especially common for the shorter reads produced by older sequencing machines, such as the Genome Analyzer II—the exact instrument used in Li et al.’s study. Cycle bias was not quite denounced at the time of Li et al.’s study, but it soon came to the attention of researchers [14, 15] and was later included as a quality control parameter in some variant callers [16, 17]. In Lin’s comment [13], it was also pointed out that some false positives might have arisen from alignment errors, due to an incomplete transcriptome reference and the complexity of correctly mapping intron-exon junction reads. At the time (2011), Li et al. used the GRCh36 version of the human reference genome. Since then two generations of reference genomes (GRCh37 and GRCh38) have succeeded GRCh36, which allow more accurate alignment and variant detection [18]. Another possible source of error pointed out in these comments and in another study by Schrider et al. [19] was the effect of paralogous loci. Schrider et al. reanalyzed the same data and found that 2206 of the original 10 210 exonic RNA-editing events reported by Li et al. had at least one paralog in the genome; they suspected that these paralog genes may harbor genomic variants that were mistakenly detected as RNA editing by Li et al. A later DNA/RNA parallel sequencing study of 18 Korean individuals found 1809 RNA-editing events [20], also substantially fewer than Li et al.’s report even after adjusting for sample size. One year after their initial study, Li et al. responded to the controversies by conducting additional sequencing and analyses [21]. In the response, the authors agreed that part of their original results were attributed to technical artifacts but insisted that the magnitude of RNA-editing events was much higher than previously anticipated.

Since the publication of Li et al.’s study, large-scale RNA-editing events have been documented by multiple studies. For example, in a study by Peng et al. [22], the authors identified 22 688 RNA-editing events, 93% of which were A➔I changes. In another study [23], Bahn et al. identified ∼10 000 RNA DNA difference (RDD)s with more than a half being A➔I substitutions. Recently, a study examined exome sequencing and RNA-Seq data of 10 subjects from The Cancer Genome Atlas [24]. Out of the 41 529 RNA DNA difference (RDD) detected, the majority were A➔I, but only 877 were documented in existing RNA-editing databases at that time. More importantly, later studies have found functional effect of A➔I RNA editing, such as the generation of alterative proteins by modifying amino acid sequences [25], potential drug sensitivity regulations [26] and increased editing activity is associated with poor prognosis [27].

Beyond A➔I and C➔U events, non-canonical RNA-editing events have been discovered within a few genes through low-throughput experiments, including U➔C [28] and G➔A changes [29, 30]. More recently, HTS studies reported appreciable amounts of non-canonical RNA-editing events [10, 22, 23]. Generally, the quantity of non-canonical changes is much lower compared to canonical ones, and their experimental validation rate was found to be lower than canonical editing events [22]. More importantly, there is currently no plausible biological mechanism to explain the non-canonical RNA-editing events. Contradictory voices call out that non-canonical RNA editing is unlikely to occur [31, 32]. Whether non-canonical RNA-editing events genuinely exist is an open question that invites more research and may require new technologies, such as direct RNA sequencing, rather than current approaches that utilize cDNA intermediates.

Bioinformatics approaches of RNA-editing identification

With accelerated characterization of human RNA edits in recent years, several methods analyzed the flanking nucleotides of known RNA-editing sites to predict undocumented RNA edits. To this end, InosinePredict [33] utilized four nucleotides upstream and downstream from the known RNA-editing events. AIRLINER [34] considered 21–41 nucleotides spanning the centering adenosine site. While the flanking sequence-based prediction methods do not require HTS data to function, the majority of published methods were built for RNA-Seq.

The first wave of studies that described pipelines to detect RNA editing from RNA-Seq data was in 2012 by Bahn et al. [23], Peng et al. [22] and Ramaswami et al. [35], all involving a single subject or cell line. These early attempts all comprised typical HTS analysis steps, including alignment, removal of duplicate reads, calling variants and variant distillation by various filters. For the alignment step, Bahn et al. jointly applied multiple aligners and imposed a ‘double-filtering’ of mismatches in the mapped reads, such upfront stringent mapping may bypass much of the need for post-filtering as concluded in a later comparative evaluation [36]. The other pipelines, on the contrary, rely heavily on post-filtering of called variants to remove errors (Figure 3B and C). Basic filters include depth (coverage) of reads, number and frequency of edited alleles, base and mapping quality etc. Cycle bias was counteracted with a removal of 5′ end reads [35] and strand filter was exerted to drop variants biased to either strand [22]. Since RNA-editing events are less likely to occur in non-Alu regions, more stringent criteria or additional filters were applied on non-Alu editing candidates [35]. Most importantly, some methods [22, 35] append a realignment step to the pipeline to ensure unique mapping, ruling out the spurious editing sites attributable to homologous genes.

In 2013, Picardi and Pesole released REDItools [37], the first software package purposed for RNA-editing detection from RNA-Seq data. A series of similar tools have been developed ever since (summarized in Table 1). In 2017, Diroma et al. systematically evaluated five tools using simulated and real data sets, and they found that most had application limitations and none was able to stand out in all assessment aspect [38]. Diroma et al.’s article also summarized general principles of RNA-Seq experiment design and compared methodological specifics of these analysis tools.

Table 1.

RNA-editing resources

| Name | First author | Year | Purpose* | PMID | Required HTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DARNED | Kiran | 2010 | Database | 20547637 [54] | N/A |

| InosinePredict | Eggington | 2011 | Prediction | 21587236 [33] | RNA-Seq |

| N/A | Ramaswami | 2012 | Detection | 22484847 [35] | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq |

| REDItools | Picardi | 2013 | Detection | 23742983 [37] | RNA-Seq, optional DNA-Seq |

| VIRGO | Distefano | 2013 | Visualization | 23815474 [78] | RNA-Seq |

| RADAR | Ramasawmi | 2013 | Database | 24163250 [55] | N/A |

| GIREMI | Zhang | 2015 | Detection | 25730491 [46] | RNA-Seq |

| RASER | Ahn | 2015 | Detection | 26323713 [79] | RNA-Seq |

| AIRLINER | Nigita | 2015 | Prediction | 25759810 [34] | RNA-Seq |

| DREAM | Alon | 2015 | Detection | 25840043 [80] | RNA-Seq |

| RES-Scanner | Wang | 2016 | Detection | 27538485 [81] | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq |

| RDDpred | Kim | 2016 | Detection | 26817607 [44] | RNA-Seq |

| N/A | Sun | 2016 | Prediction | 27764195 [82] | N/A |

| RNAEditor | John | 2017 | Detection | 27694136 [49] | RNA-Seq |

| REDiportal | Picardi | 2017 | Database | 27587585 [56] | N/A |

| RED-ML | Xiong | 2017 | Detection | 28328004 [45] | RNA-Seq, optional DNA-Seq |

| JACUSA | Piechotta | 2017 | Detection | 28049429 [41] | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq |

| RNA Editing Plus | Yao | 2017 | Detection, Annotation | 28968662 [47] | RNA-Seq |

| LNCediting | Gong | 2017 | Annotation | 27651464 [58] | N/A |

| miREDB | Li | 2017 | Annotation | 29233923 [57] | N/A |

*Prediction: predicting unknown RNA-editing sites from genome or RNA sequences without the necessity of HTS data. Detection: discrimination of plausible RNA-editing sites from raw variants called from HTS data. Annotation: characterizing reported RNA-editing sites with potential functional roles as to protein coding distortion and dysregulation of non-coding RNAs.

Table 2.

Resources of variants calling from RNA-Seq.

| Name | First author | Year | Purpose | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNVQ | Duitama | 2012 | SNP detection | 22537301 [66] |

| FX | Hong | 2012 | Cloud Computing, SNP Detection | 22257667 [67] |

| SNPiR | Piskol | 2013 | SNP detection | 24075185 [68] |

| GATK | McKenna | 2010 | SNP indel detection | 20644199 [70] |

| GLMVC | Sheng | 2016 | Somatic mutation detection | 27046520 [16] |

| Goby 3.0 | Torracinta | 2016 | Somatic mutation detection | [83] |

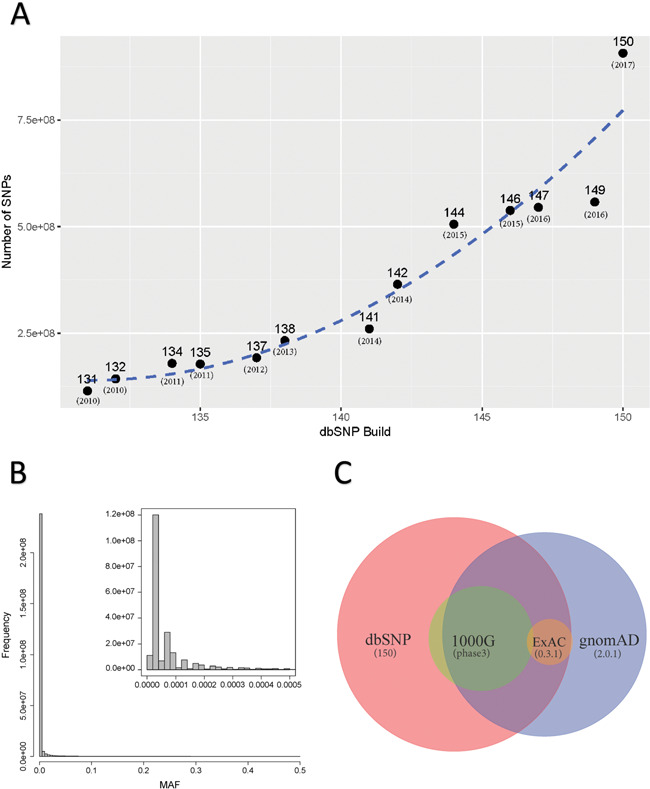

The RNA-editing detection tools can be categorized by whether they require paired DNA–RNA HTS data or only RNA-Seq data (Figure 3E). Having paired DNA and RNA-Seq data is the most ideal scenario, as practiced in the aforementioned three early studies [22, 23, 35]. Given paired DNA–RNA HTS data, RNA-editing events are identified as alleles present in RNA yet absent in DNA (Figure 3E). In a way, this process is similar to somatic mutation detection where a tumor DNA sample is compared against a normal DNA control, so, unsurprisingly, somatic mutation detection tools such as MuTect [39] are frequently repurposed to identify RNA-editing sites [40, 41]. The DNA–RNA-paired design inevitably ignores much data afforded by DNA-Seq because the overlapping regions between exome sequencing and RNA-Seq are only ∼50% [16]. Moreover, in public data repositories, the vast volume of accumulated RNA-Seq data does not have paired DNA-Seq data. Therefore, many tools opted to detect RNA-editing events without requiring paired DNA-Seq data (Table 1, Figure 3E). In the absence of DNA-Seq data, the common approach is to sacrifice sensitivity for specificity by removing all SNPs documented in dbSNP [42]. However, the size of dbSNP has increased nearly exponentially with the recent releases (Figure 4). The latest version, dbSNP150 for humans contains nearly 1 billion records. Consequently, filtering against dbSNP can potentially remove a significant portion of genuine RNA-editing events. Therefore, utilization of dbSNP should be restricted to SNPs with high minor allele frequency (e.g. >5%). Lately, exome or whole-genome sequencing of large human cohorts has resulted in alternative SNP resources such as ExAC and gnomAD [43]. One advantage with these resources is that documented SNPs are always annotated with population frequency, therefore allowing for flexible filtration by prevalence.

Figure 4.

(A) Number of dbSNPs increased near exponentially from version 149 to 150. However, only 14.3% of the SNPs currently in dbSNP150 have MAF information. (B) Minor allele frequencies were extract from gnomAD and then plotted. This demonstrates that majority of SNPs detected currently are of very low MAF. Filtering by any SNP resources should only be done for SNPs with high MAF. (C) Venn diagram shows the relationship with the four big SNP resources.

More recently, machine learning approaches have emerged in RNA-editing studies, where read-alignment features are modeled to predict the RNA-editing event’s correctness (Figure 3C). RDDpred [44] deploys a Random Forest model working on 15 features grouped into 6 categories, e.g. read depth, mapping quality etc. RED-ML [45] uses logistic regression to infer the probability that an SNV detected from RNA-Seq is an RNA-editing event, adjusting for read depth, mapping quality, known RNA-editing databases and other common features. In these machine learning approaches as well as another method GIREMI [46], previously known RNA edits were identified to form a positive example set, whereas common SNPs or simulated mismatches were taken as negative examples (Figure 3D). In 2017, RNA Editing Plus [47], a platform for RNA-editing (A➔I) identification and functional annotation was released. This platform integrates multiple existing tools to predict RNA-editing events from RNA-Seq data and catalogued the editing sites into functional regions of microRNAs (pri-, pre- and mature) and mRNAs (pre- and mature). The authors allegedly found more than 60 000 RNA-editing events in human coding genes, and they observed that some RNA-editing events are preferentially located in regulatory sequences, including splicing junction sites, microRNA seed regions and untranslated regions.

Furthermore, multiple groups found RNA-editing sites tend to form ‘clusters’ [48], ‘editing islands’ [49] or ‘hyper-editing regions’ [50, 51] in the human genome. Alternative pipelines [49, 50] were devised to detect hyper-editing clusters through alignment of unmapped RNA-Seq reads with loosened mismatch tolerance. Another trending analysis is quantitative RNA-editing analysis, which represents a major forward step from the current focus of RNA-editing identification. JACUSA [41] is a pioneer in this front and it was designed to differentiate the editing levels of the same RNA-editing site among different experimental conditions (Figure 3E).

The efforts to catalog known RNA-editing events can be traced back as early as 2007 with the establishment of two databases: dbRES [52] and REDIdb [53]. These early attempts at curating RNA-editing events did not take advantage of HTS technology and were not maintained on a regular basis. Another RNA-editing database, DARNED [54], was released in 2010 with primary focus on humans, and in 2013 it was extended to drosophila and mouse. To date, DARNED contains 333 215 human (GRCh37), 1968 drosophila (DM3) and 8340 mouse (MM10) RNA-editing events. In addition, RADAR [55] was released in 2013 as an RNA-editing event database that contains 2 461 955 human (GRCh37), 5025 drosophila (DM3) and 8823 (MM9) mouse RNA-editing events in its current version. Finally, the largest and most comprehensive collection of RNA editing in humans was delivered in 2017 through REDIportal [56], which absorbs DARNED and RADAR annotations and contains a total of 4 668 508 RNA-editing events. Besides these general databases dominated by protein coding genes, specialized resources focusing on RNA editing in the non-coding transcriptome have arisen. These latest efforts led to the birth of miREDB [57] and LNCediting [58], which report RNA-editing events in multiple species (including humans) that are pertinent to microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs, respectively. It is worth noting that these RNA-editing databases contain non-canonical RNA-editing events.

Beyond RNA editing: single-nucleotide genomic variants in RNA

Another major type of SNV detectable through RNA-Seq is genomic SNV. Researchers found that RNA-Seq is a good alternative resource for calling variants in genes with sufficiently high expression levels [59]. In the conventional application of RNA-Seq, approximate alignment of RNA-Seq reads within the gene span suffices to quantify gene expression adequately. Nevertheless, accurate alignment down to the individual nucleotide is required to call genomic variants. As revealed in the aforementioned controversies surrounding Li et al.’s RNA-editing study, variants called from HTS data are mingled with artifacts resulting from sequencing error and alignment complications (Figure 3A). Due to factors like incomplete transcriptome, inexact exon-intron junctions and Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) duplication errors [60], a higher level of noise has been observed in RNA-Seq than in DNA-Seq [16, 24, 61]. In addition, given the prevalence of RNA-editing events, care must be exercised to distinguish RNA edits from DNA variants (Figure 3A). Thus, identification of genomic variants from RNA-Seq data poses stronger bioinformatics challenges than doing so from DNA-Seq data.

Among early endeavors to call variants from RNA-Seq data, a primitive strategy was to analyze RNA-Seq data as if they were DNA-Seq data, without accounting for RNA-Seq-specific characteristics. In 2009, Chepelev et al. first tried out this strategy in their analysis of RNA-Seq data of two cell lines [62]. This study did not involve DNA-Seq, and no RNA-Seq quality control filters were applied. Thereafter, quite a few studies [63–65] have followed the same approach to call DNA variants from RNA-Seq data. However, such naive strategies are likely to result in a large amount of false positives. More prudent approaches to calling variants from RNA-Seq data usually require a higher standard for quality control than is routinely practiced in DNA-Seq studies [36]. Besides the common quality control parameters, additional filters frequently applied include mapping uniqueness and distance to junction, which are also relevant to RNA-editing detection (Figure 3B and C).

In recent years, the bioinformatics developments surrounding RNA-Seq variant detection has accelerated (Figure 3E). Tools tailored specifically for inferring genomic variants from RNA-Seq data emerged in 2012 with the release of SNVQ [66] and FX [67]. These early tools did not give much thought to the unique characteristics of RNA. In 2013, SNPiR [68] implemented a series of filters discussed above (Figure 3B) into a streamlined pipeline. It increased the specificity of variant detection by removing a large amount of spurious variants, especially those in homopolymer runs or proximity to splice junctions. However, SNPiR’s study had limitations as it was conducted using two cell lines. Consisting of pure cancer cells that lack real-life heterogeneity, cell lines enable a lowered complexity of variant calling compared with tumor samples. In the same year, Quinn et al. [69] made several instructive conclusions after evaluating eight strategies for calling SNVs from RNA-Seq data. They found that aligning to a genome reference produced more SNVs than aligning to a transcriptome reference, but these additional SNVs could be errors resulting from aligning transcript reads to the unspliced genome. Another finding was that post-alignment removal of duplicate reads led to higher specificity. In 2014, GATK [70], the most authoritative HTS data processing and variant calling pipeline, released best-practice protocols for RNA-Seq data, signifying the official advent of the era of calling variants from RNA-Seq data.

Among all variant calling efforts, a very attractive application is to identify somatic mutations, which are frequently associated with cancers. Classically, calling somatic mutations requires paired DNA-Seq samples from disease tissues and normal controls, and RNA-Seq was recruited only for verifying the penetrance of somatic mutations in the transcriptome. Recently, researchers began to make ab initio discovery of somatic mutations from paired RNA-Seq samples [71] (Figure 3E). Inferring somatic mutation from a pair of RNA-Seq samples poses extra difficulties due to the additional noise and errors introduced by the second sample. The cross contamination between tumor and adjacent normal tissues can substantially impair the detection integrity [72] for somatic mutations. In 2016, GLMVC [16] leveraged a bias reduced generalized linear model to identify somatic mutation candidates from RNA-Seq data. This program accommodated most of the unique filters pertaining to RNA-Seq data (Figure 3B).

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Variant calling was traditionally performed on DNA-Seq data. Due to the disproportional popularity and accelerated data accumulation of RNA-Seq, a trending strategy is to mine variants in RNA-Seq data. In the early phase, paired DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq data sets were conjectured as an ideal and desirable setting, especially for the sake of detecting RNA editing. Soon after, most bioinformatics tools waived the prerequisite of DNA-Seq data for detecting RNA editing. DNA-Seq and RNA-Seq can demonstrate a big discrepancy in their covered genome regions. DNA-Seq, such as exome sequencing, targets all known and putative exons, only part of which are expressed in a particular biological sample [73, 74]. RNA-Seq targets all transcribed genome regions, which may surpass the capture boundary of exome sequencing [75]. To maximize exploitation of the abundant RNA-Seq data, many bioinformatics tools for RNA-editing detection require RNA-Seq data only, some allowing for optional input of DNA-Seq data.

Detection of RNA SNV from RNA-Seq data remains a challenging task and it needs to be addressed both technically and bioinformatically. Compared to DNA-Seq, RNA-Seq data are subjected to more sequencing errors, these can be addressed by improved library preparation and more accurate sequencing technology. Lately, there are novel sequencing techniques developed for RNA-editing detection, including cyanoethylation-based inosine chemical erasing sequencing [76] and microfluidics-based multiplex PCR coupled with deep sequencing [77]. These technologies might hold the promise for resolving the inconclusive questions in human RNA editome. Bioinformatically, most RNA-Seq studies have resorted to general RNA aligners, which adopt an exon-first approach to transcriptome reconstruction. Several groups [19, 31, 32] have pointed out that paralogous genes or intronless pseudogenes can falsely inflate the detected RNA editing. Strategies such as realignment to ensure unique mapping and control for reads with multiple best matches should be employed.

The inference of SNVs using HTS data involves finding the perfect balance between sensitivity and specificity. This is especially true for RNA-Seq. In our opinion, RNA-Seq works better as a source of genomic variants when specificity is weighted over sensitivity due to the extra complications involved in RNA-Seq compared to DNA-Seq. For screening genomic variants in the entire genome, DNA-Seq remains superior for technical reasons aforementioned. Given the high false-positive rate, the integrity of SNV detected in RNA-Seq rests on the validation with additional methods such as PCR and Sanger sequencing.

The stunning discovery of more than 10 thousand human RNA-editing sites made by Li et al. [10] triggered a series of refutations and defenses, which in consequence led to a consensus that accurate identification of variants using RNA-Seq data requires meticulous filters or models to rule out artifacts. While flawed with immature technique and imperfect analysis, Li et al.’s work propelled the research of RNA editing forward and fueled intense bioinformatics development for variant calling in RNA-Seq data. The case of Li et al.’s study was a perfect example of how science research in general is a scenario of trials and errors.

Key Points

High-throughput sequencing accelerated the research of RNA editing substantially.

The prevalence of RNA-editing events in the human genome is higher than previously thought.

RNA-Seq data has been used to detect SNVs at the cost of higher false-discovery rate compared to DNA-Seq data.

Functional effects of A➔I editing have been demonstrated.

Yan Guo is an associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, University of New Mexico. He is also the Director of Bioinformatics Shared Resources for University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Hui Yu is a research fellow at the University of New Mexico, Comprehensive Cancer Center, her research areas include cancer genomics, genetics and computational methodology.

David C. Samuels is an associate professor at the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics at Vanderbilt University. His research interests include mitochondria, population genetics and computational model.

Wei Yue is a research fellow at the University of New Mexico, Comprehensive Cancer Center. His research focused on plant genetics.

Scott Ness is a Professor of Cancer Genomics and Director of the genomics and bioinformatics shared resource, Dr. Ness focuses on translational genetics and molecular medicine. The Ness laboratory uses innovative approaches to study topics at the interface between cancer biology, molecular biology, stem cells, differentiation, transcription, epigenetics and genomics. The research in the Ness laboratory focuses on the activities and regulation of Myb transcription factors.

Ying-yong Zhao is a professor at the Northwest University China. His research is focused on genomics and genetics of chronic kidney disease.

References

- 1. van Dijk EL, Auger H, Jaszczyszyn Y, et al. Ten years of next-generation sequencing technology. Trends Genet 2014;30:418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17:333–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meier JC, Kankowski S, Krestel H, et al. RNA editing-systemic relevance and clue to disease mechanisms? Front Mol Neurosci 2016;9:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brennicke A, Marchfelder A, Binder S. RNA editing. FEMS Microbiol Rev 1999;23:297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol 2004;2:e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001;409:860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, et al. Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nat Biotechnol 2004;22:1001–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li JB, Levanon EY, Yoon JK, et al. Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science 2009;324:1210–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wahlstedt H, Daniel C, Enstero M, et al. Large-scale mRNA sequencing determines global regulation of RNA editing during brain development. Genome Res 2009;19:978–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li M, Wang IX, Li Y, et al. Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. Science 2011;333:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pickrell JK, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Comment on “Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome”. Science 2012;335:53–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kleinman CL, Majewski J. Comment on “Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome”. Science 2012;335:1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin W, Piskol R, Tan MH, et al. Comment on “Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome”. Science 2012;335:1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo Y, Ye F, Sheng Q, et al. Three-stage quality control strategies for DNA re-sequencing data. Brief Bioinform 2014;15:879–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schirmer M, Ijaz UZ, D'Amore R, et al. Insight into biases and sequencing errors for amplicon sequencing with the Illumina MiSeq platform. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sheng QH, Zhao SL, Li CI, et al. Practicability of detecting somatic point mutation from RNA high throughput sequencing data. Genomics 2016;107:163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2011;27:2987–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo Y, Dai YL, Yu H, et al. Improvements and impacts of GRCh38 human reference on high throughput sequencing data analysis. Genomics 2017;109:83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schrider DR, Gout JF, Hahn MW. Very few RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. PLoS One 2011;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ju YS, Kim JI, Kim S, et al. Extensive genomic and transcriptional diversity identified through massively parallel DNA and RNA sequencing of eighteen Korean individuals. Nat Genet 2011;43:745–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li MY, Wang IX, Cheung VG. Response to comments on "Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome". Science 2012;335:1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peng ZY, Cheng YB, Tan BCM, et al. Comprehensive analysis of RNA-Seq data reveals extensive RNA editing in a human transcriptome. Nat Biotechnol 2012;30:253–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bahn JH, Lee JH, Li G, et al. Accurate identification of A-to-I RNA editing in human by transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res 2012;22:142–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo Y, Zhao SL, Sheng QH, et al. The discrepancy among single nucleotide variants detected by DNA and RNA high throughput sequencing data. BMC Genomics 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peng X, Xu X, Wang Y, et al. A-to-I RNA editing contributes to proteomic diversity in cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33:817–28.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Han L, Diao L, Yu S, et al. The genomic landscape and clinical relevance of A-to-I RNA editing in human cancers. Cancer Cell 2015;28:515–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paz-Yaacov N, Bazak L, Buchumenski L, et al. Elevated RNA editing activity is a major contributor to transcriptomic diversity in tumors. Cell Rep 2015;13:267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sharma PM, Bowman M, Madden SL, et al. RNA editing in the Wilms‘ tumor susceptibility gene, WT1. Genes Dev 1994;8:720–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klimek-Tomczak K, Mikula M, Dzwonek A, et al. Editing of hnRNP K protein mRNA in colorectal adenocarcinoma and surrounding mucosa. Br J Cancer 2006;94:586–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niavarani A, Currie E, Reyal Y, et al. APOBEC3A is implicated in alpha novel class of G-to-A mRNA editing in WT1 transcripts. PLoS One 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Piskol R, Peng Z, Wang J, et al. Lack of evidence for existence of noncanonical RNA editing. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:19–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kleinman CL, Adoue V, Majewski J. RNA editing of protein sequences: a rare event in human transcriptomes. RNA 2012;18:1586–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eggington JM, Greene T, Bass BL. Predicting sites of ADAR editing in double-stranded RNA. Nat Commun 2011;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nigita G, Alaimo S, Ferro A, et al. Knowledge in the investigation of A-to-I RNA editing signals. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2015;3:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ramaswami G, Lin W, Piskol R, et al. Accurate identification of human Alu and non-Alu RNA editing sites. Nat Methods 2012;9:579–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JH, Ang JK, Xiao X. Analysis and design of RNA sequencing experiments for identifying RNA editing and other single-nucleotide variants. RNA 2013;19:725–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Picardi E, Pesole G. REDItools: high-throughput RNA editing detection made easy. Bioinformatics 2013;29:1813–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Diroma MA, Ciaccia L, Pesole G, et al. Elucidating the editome: bioinformatics approaches for RNA editing detection. Brief Bioinform 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Porath HT, Schaffer AA, Kaniewska P, et al. A-to-I RNA editing in the earliest-diverging eumetazoan phyla. Mol Biol Evol 2017;34:1890–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Piechotta M, Wyler E, Ohler U, et al. JACUSA: site-specific identification of RNA editing events from replicate sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017;18:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ramaswami G, Zhang R, Piskol R, et al. Identifying RNA editing sites using RNA sequencing data alone. Nat Methods 2013;10:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim MS, Hur B, Kim S. RDDpred: a condition-specific RNA-editing prediction model from RNA-seq data. BMC Genomics 2016;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xiong H, Liu DB, Li QY, et al. RED-ML: a novel, effective RNA editing detection method based on machine learning. Gigascience 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Q, Xiao XS. Genome sequence-independent identification of RNA editing sites. Nat Methods 2015;12:347–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yao L, Wang H, Song Y, et al. Large-scale prediction of ADAR-mediated effective human A-to-I RNA editing. Brief Bioinform 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Danecek P, Nellaker C, McIntyre RE, et al. High levels of RNA-editing site conservation amongst 15 laboratory mouse strains. Genome Biol 2012;13:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. John D, Weirick T, Dimmeler S, et al. RNAEditor: easy detection of RNA editing events and the introduction of editing islands. Brief Bioinform 2017;18:993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Porath HT, Carmi S, Levanon EY. A genome-wide map of hyper-edited RNA reveals numerous new sites. Nat Commun 2014;5:4726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Carmi S, Borukhov I, Levanon EY. Identification of widespread ultra-edited human RNAs. PLoS Genet 2011;7: e1002317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. He T, Du P, Li Y. dbRES: a web-oriented database for annotated RNA editing sites. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:D141–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Picardi E, Regina TMR, Brennicke A, et al. REDIdb: the RNA editing database. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:D173–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kiran A, Baranov PV. DARNED: a DAtabase of RNa EDiting in humans. Bioinformatics 2010;26:1772–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ramaswami G, Li JB. RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Picardi E, D'Erchia AM, Lo Giudice C, et al. REDIportal: a comprehensive database of A-to-I RNA editing events in humans. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:D750–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li L, Song Y, Shi X, et al. The landscape of miRNA editing in animals and its impact on miRNA biogenesis and targeting. Genome Res 2018;28:132–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gong J, Liu C, Liu W, et al. LNCediting: a database for functional effects of RNA editing in lncRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:D79–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cirulli ET, Singh A, Shianna KV, et al. Screening the human exome: a comparison of whole genome and whole transcriptome sequencing. Genome Biol 2010;11:R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bansal V. A computational method for estimating the PCR duplication rate in DNA and RNA-seq experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang P, Samuels DC, Lehmann B, et al. Mitochondria sequence mapping strategies and practicability of mitochondria variant detection from exome and RNA sequencing data. Brief Bioinform 2015;42:D109–D113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chepelev I, Wei G, Tang Q, et al. Detection of single nucleotide variations in expressed exons of the human genome using RNA-Seq. Nucleic Acids Res 2009;37:e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Miller AC, Obholzer ND, Shah AN, et al. RNA-seq-based mapping and candidate identification of mutations from forward genetic screens. Genome Res 2013;23:679–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yoon K, Lee S, Han TS, et al. Comprehensive genome- and transcriptome-wide analyses of mutations associated with microsatellite instability in Korean gastric cancers. Genome Res 2013;23:1109–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Heap GA, Yang JH, Downes K, et al. Genome-wide analysis of allelic expression imbalance in human primary cells by high-throughput transcriptome resequencing. Hum Mol Genet 2010;19:122–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Duitama J, Srivastava P, Mandoiu I. Towards accurate detection and genotyping of expressed variants from whole transcriptome sequencing data. BMC Genomics 2012;13:S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hong D, Rhie A, Park SS, et al. FX: an RNA-Seq analysis tool on the cloud. Bioinformatics 2012;28:721–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Piskol R, Ramaswami G, Li JB. Reliable identification of genomic variants from RNA-seq data. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:641–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Quinn EM, Cormican P, Kenny EM, et al. Development of strategies for SNP detection in RNA-seq data: application to lymphoblastoid cell lines and evaluation using 1000 genomes data. PLoS One 2013;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Xu X, Zhu K, Liu F, et al. Identification of somatic mutations in human prostate cancer by RNA-Seq. Gene 2013;519:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wei L, Papanicolau-Sengos A, Liu S, et al. Pitfalls of improperly procured adjacent non-neoplastic tissue for somatic mutation analysis using next-generation sequencing. BMC Med Genomics 2016;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Su AI, Cooke MP, Ching KA, et al. Large-scale analysis of the human and mouse transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:4465–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ramskold D, Wang ET, Burge CB, et al. An abundance of ubiquitously expressed genes revealed by tissue transcriptome sequence data. PLoS Comput Biol 2009;5: e1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. O'Brien TD, Jia P, Xia J, et al. Inconsistency and features of single nucleotide variants detected in whole exome sequencing versus transcriptome sequencing: A case study in lung cancer. Methods 2015;83:18–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Suzuki T, Ueda H, Okada S, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of adenosine-to-inosine editing using the ICE-seq method. Nat Protoc 2015;10:715–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhang R, Li X, Ramaswami G, et al. Quantifying RNA allelic ratios by microfluidic multiplex PCR and sequencing. Nat Methods 2014;11:51–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Distefano R, Nigita G, Macca V, et al. VIRGO: visualization of A-to-I RNA editing sites in genomic sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ahn J, Xiao XS. RASER: reads aligner for SNPs and editing sites of RNA. Bioinformatics 2015;31:3906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Alon S, Erew M, Eisenberg E. DREAM: a webserver for the identification of editing sites in mature miRNAs using deep sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015;31:2568–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang ZJ, Lian JM, Li QY, et al. RES-Scanner: a software package for genome-wide identification of RNA-editing sites. Gigascience 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sun J, De Marinis Y, Osmark P, et al. Discriminative prediction of A-To-I RNA editing events from DNA sequence. PLoS One 2016;11: e0164962. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Torracinta R, Mesnard L, Levine S, et al. Adaptive somatic mutations calls with deep learning and semi-simulated data. bioRxiv2016.