Abstract

Background

Concerns have been raised on a potential interaction between renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASI) and the susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). No data have been so far reported on the prognostic impact of RASI in patients suffering from ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during COVID-19 pandemic, which was the aim of the present study.

Methods

STEMI patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) and enrolled in the ISACS-STEMI COVID-19 registry were included in the present sub-analysis and divided according to RASI therapy at admission.

Results

Our population is represented by 6095 patients, of whom 3654 admitted in 2019 and 2441 in 2020. No difference in the prevalence of SARSCoV2 infection was observed according to RASI therapy at admission (2.5% vs 2.1%, p = 0.5), which was associated with a significantly lower mortality (adjusted OR [95% CI]=0.68 [0.51–0.90], P = 0.006), confirmed in the analysis restricted to 2020 (adjusted OR [95% CI]=0.5[0.33–0.74], P = 0.001). Among the 5388 patients in whom data on in-hospital medication were available, in-hospital RASI therapy was associated with a significantly lower mortality (2.1% vs 16.7%, OR [95% CI]=0.11 [0.084–0.14], p < 0.0001), confirmed after adjustment in both periods. Among the 62 SARSCoV-2 positive patients, RASI therapy, both at admission or in-hospital, showed no prognostic effect.

Conclusions

This is the first study to investigate the impact of RASI therapy on the prognosis and SARSCoV2 infection of STEMI patients undergoing PPCI during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both pre-admission and in-hospital RASI were associated with lower mortality. Among SARSCoV2-positive patients, both chronic and in-hospital RASI therapy showed no impact on survival.

Keywords: Renin-Angiotensin System inhibitors, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, Mortality, COVID-19, Percutaneous coronary intervention

1. Background

The global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has dramatically impacted on healthcare and its effects are ongoing. As of 8 September 2020, more than 27 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in more than 185 countries and territories, resulting in over 90,000 deaths, especially in Europe, the United States and Latin America.

Large interests have been focused on a potential harmful effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), the so-called renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASI) in infected patients. These therapies were suspected to condition the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect the cells through an upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 cell entry [1], [2]. The increased expression of ACE2 under RASI was suspected to increase the patient’s susceptibility to COVID-19, and the large prevalence of hypertension among patients affected by COVID-19 has raised the fear of contagion and worsened the clinical outcome among patients with cardiovascular disease. This might have affected prescription and the patients’ compliance to such therapy. Professional societies and opinion leaders have overcome this uncertainty by recommending that patients receiving ACE-inhibitors and ARBs should continue taking their medication until the results of powered outcome studies become available [3], [4], [5].

Data emerging from selected cohorts have suggested, to date, that ACEI/ARB use was not associated with increased risk of COVID-19 or worse outcomes among those with infection [6], [7], [8]. However, no data have been, so far, reported in patients suffering from ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a very high-risk population with a large use of RASI.

The International Study on Acute Coronary Syndromes – ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (ISACS-STEMI) COVID-19 was established in response to the emerging outbreak of COVID-19, aiming at providing a European snapshot and estimating the true impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the treatment and outcome of STEMI patients treated by PPCI. The aim of this analysis was to investigate whether the use of RASI at the time of hospitalization was associated with the susceptibility to COVID-19 and with an increased mortality risk.

2. Study design and population

Our study population is represented by patients enrolled in the ISACS-STEMI COVID-19 (NCT 04412655), a multicenter registry including STEMI patients enrolled by 77 high-volume European primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centers, which was conducted to compare STEMI patients treated from March 1st until April 30th of 2019 with those admitted within the same period of 2020.

We collected demographic, clinical, procedural data, data on total ischemia time, door-to-balloon time, referral to primary PCI facility, PCI procedural data and in-hospital mortality. Follow-up was performed for the duration of the hospitalization. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was performed by molecular nasal/oropharyngeal swab, according to the single center protocols. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of AOU Maggiore della Carità, Novara.

2.1. Patients and public involvement

Not applicable since recruitment was retrospective and anonymous.

2.2. Statistics

Data analysis was performed by using SPSS Statistics Software 23.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and supervised by an experienced independent statistician (GC). Quantitative variables were described using median and interquartile range. Absolute frequencies and percentages were used for qualitative variables. ANOVA or Mann-Whitney and the chi-square test were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Normal distribution of continuous variables was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

As previously described [9], a propensity score analysis was performed in order to overcome the potential bias related to the differences in baseline characteristics. For each patient, a propensity score indicating the likelihood of having chronic or in-hospital RASI administration was calculated by the use of forward logistic regression analysis that identified variables independently associated with RASI prescription.

The discriminatory capacity of the propensity score was assessed by the area under the ROC curve (c-statistic) as an index of model performance [10]. On the basis of the propensity score, the population was divided in four groups (from the lowest to the highest probability to have RASI prescribed) by the use of quartiles. The impact of RASI on mortality and SARS-2 positivity was evaluated for each quartile, separately.

Furthermore, multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the association of RASI with in-hospital mortality and SARS-CoV-2 infection after adjustment for baseline confounding factors between the two groups, including the propensity score. All variables of interest (set at a P‐value < 0.1) were entered in block into the model. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data coordinating center was established at the Eastern Piedmont University, Novara, Italy.

3. Results

The study population comprises a total of 6095 STEMI patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion, in whom complete demographic, clinical, procedural, and outcome data were available as well as information regarding chronic RASI therapy at admission. Median age was 64 [55–73] years, including 4517 males (74.1%). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients with versus without chronic RASI therapy at admission, according to the year of treatment. Several differences were observed in baseline characteristics, similarly observed in 2019 and 2020. Patients on RASI were older, more often female, suffering from diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, previous STEMI, previous coronary revascularization, but less often active smokers. Patients on RASI had a longer door-to-balloon and total ischemia time. Patients on RASI had less often out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock, especially in 2020 (7.5% vs 10.2%, p = 0.02). No difference was observed between 2019 and 2020 in terms of RASI discontinuation after hospital admission (information available in 5388 patients: 21.2% in 2019 vs 20.6% in 2020).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics according to chronic RASI therapy at admission.

| OVERALL POPULATION (N = 6095) |

YEAR 2019 (N = 3389) |

YEAR 2020 (N = 2706) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASI (n = 2441) | No RASI 2019 (n = 3654) | P value | RASI (n = 1375) | No RASI 2019 (n = 2014) | P value | RASI (n = 1066) | No RASI 2020 (n = 1640) | P value | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 67 [58–75] | 62 [53–71] | < 0.001 | 67 [58–75] | 62 [53–71] | < 0.001 | 67 [59–75] | 62 [53–71] | < 0.001 |

| Age > 75 year – n. (%) | 664 (27.2) | 633 (17.6) | < 0.001 | 373 (27.1) | 358 (17.8) | < 0.001 | 291 (27.3) | 275 (16.8) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender – n. (%) | 1801 (71.3) | 2870 (75.8) | < 0.001 | 969 (70.5) | 1527 (75.8) | 0.001 | 765 (71.8) | 1256 (76.6) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes Mellitus- n (%) | 758 (31.1) | 568 (15.5) | < 0.001 | 428 (31.1) | 316 (15.7) | < 0.001 | 330 (31) | 252 (15.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension- n (%) | 2170 (88.9) | 1148 (31.4) | < 0.001 | 1234 (89.7) | 634 (31.5) | < 0.001 | 936 (87.8) | 514 (31.3) | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia - n (%) | 1225 (50.2) | 1350 (36.9) | < 0.001 | 679 (49.4) | 739 (36.7) | < 0.001 | 546 (51.2) | 611 (37.3) | < 0.001 |

| Active Smokers – n (%) | 895 (36.7) | 1639 (44.9) | < 0.001 | 514 (37.4) | 901 (44.7) | < 0.001 | 381 (35.7) | 738 [45] | < 0.001 |

| Family History of CAD - n (%) | 550 (22.5) | 859 (23.5) | 0.37 | 319 (23.2) | 479 (23.8) | 0.71 | 231 (21.7) | 380 (23.2) | 0.37 |

| Previous STEMI- n (%) | 396 (16.2%) | 184 (5.0) | < 0.001 | 219 (15.9) | 101 (5) | < 0.001 | 177 (16.6) | 83 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| Previous PCI – n (%) | 500 (20.5) | 269 (7.4) | < 0.001 | 276 (20.1) | 154 (7.6) | < 0.001 | 224 (21) | 115 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Previous CABG - n (%) | 67 (2.7) | 40 (1.1) | < 0.001 | 30 (2.2) | 27 (1.3) | 0.08 | 37 (3.5) | 13 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Referral to Primary PCI Hospital | |||||||||

| Ambulance (from community) – n (%) | 1304 (53.4) | 2057 (56.3) | 0.027 | 717 (52.1) | 1091 (54.2) | 0.25 | 587 (55.1) | 966 (58.9) | 0.049 |

| Time delays | |||||||||

| Ischemia time, median [25–75th] | 200 [130–358] | 184 [120–310] | < 0.001 | 200 [1125–330] | 180 [120–300] | 0.009 | 210 [135–385] | 195 [125–330] | 0.006 |

| Total Ischemia time > 12 h – n (%) | 270 (11.1) | 348 (9.5) | 0.051 | 123 (8.9) | 184 (9.1) | 0.85 | 147 (13.8) | 164 (10.0) | 0.003 |

| Door-to-balloon time, median [25–75th] | 40 [25–60] | 35 [22–60] | < 0.001 | 38 [25–60] | 32 [21–60] | 0.006 | 40 [28–63] | 35 [24–60] | < 0.001 |

| Door-to-balloon time > 30 min (%)– n (%) | 1490 (61.1) | 1936 [53] | < 0.001 | 800 (58.2) | 1038 (51.6) | < 0.001 | 690 (64.8) | 898 (54.8) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical Presentation | |||||||||

| Anterior STEMI – n (%) | 1079 (44.2) | 1695 (46.4) | 0.093 | 607 (44.1) | 941 (46.7) | 0.14 | 472(44.3) | 754 [46] | 0.41 |

| Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest – n (%) | 134 (5.5) | 280 (7.7) | 0.001 | 77 (5.6) | 148 (7.3) | 0.045 | 57 (5.3) | 132 (8) | 0.007 |

| Cardiogenic shock– n (%) | 198 (8.1) | 314 (8.6) | 0.51 | 118 (8.6) | 147 (7.3) | 0.17 | 80 (7.5) | 167 (10.2) | 0.02 |

| Rescue PCI for failed thrombolysis – n (%) | 93 (3.8) | 126 (3.4) | 0.46 | 51 (3.7) | 73 (3.6) | 0.93 | 42 (3.9) | 53 (3.2) | 0.34 |

*Mann-Whitney test

CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; STEMI = ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; CABG 0 Coronary Artery Bypass Graft;

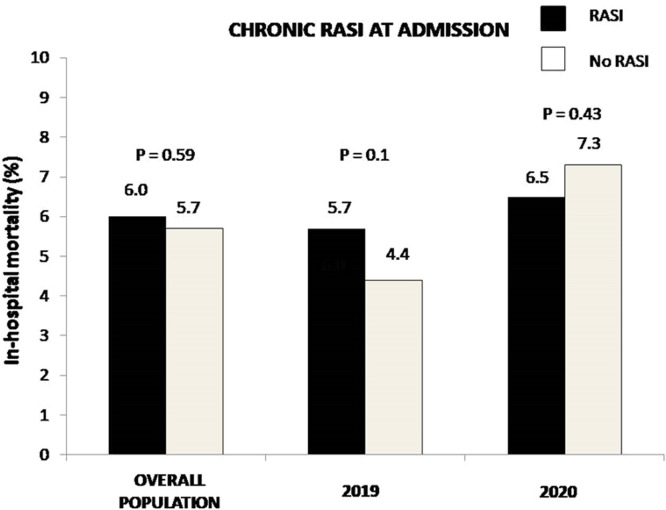

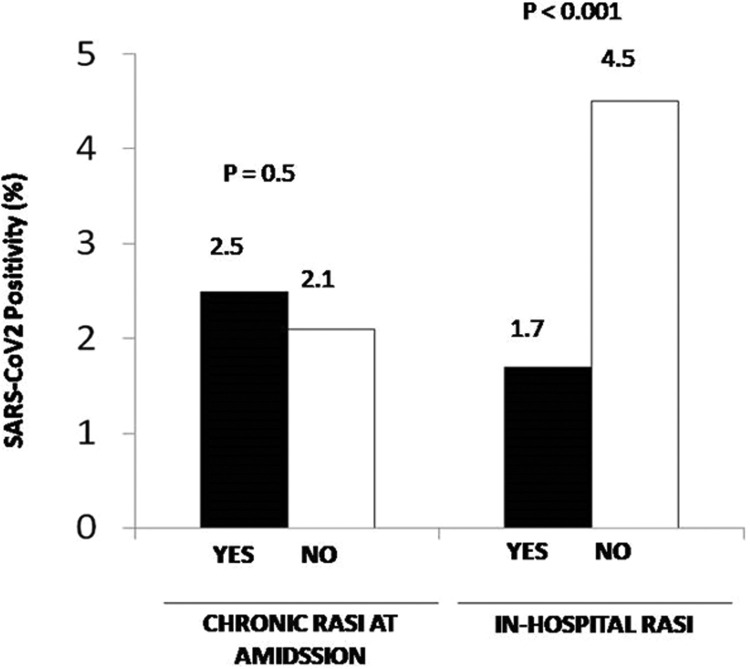

Angiographic and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 1S. RASI patients underwent less frequently PPCI via a radial approach and had less often DES implanted, but presented more often with in-stent thrombosis and multivessel disease. The duration of follow-up (hospitalization) was 5 [3–7] days. No difference was observed for in-hospital mortality (6.0% vs 5.7%, OR [95% CI] = 0.94 [0.76–1.17], p = 0.59, Fig. 1). Fig. 1S shows the impact of chronic RASI therapy in each quartile of the propensity score. In most of them, chronic RASI therapy was associated with a trend in beneficial effects. In fact, after adjustment for all baseline confounding factors, including the propensity score, chronic RASI therapy was associated with lower mortality (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.67 [0.51–0.89], p = 0.005). In the analysis restricted to 2020, we confirmed the benefits in mortality (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.5 [0.33–0.74], P = 0.001). Furthermore, between patients with vs. without chronic RASI therapy, no difference was observed in the prevalence of SARS-CoV2 infection (n = 62) (2.5% vs 2.1%, OR [95% CI] = 1.19 [0.72–1.98], p = 0.5, adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.06 [0.56–2.0], p = 0.86) ( Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Bar graphs show in-hospital mortality in overall population, in 2019 and 2020 patients according to chronic RASI therapy at admission.

Fig. 2.

Bar graphs show the prevalence of SARS-CoV2 infection in patients treated in 2020 according to chronic RASI therapy at admission (left graph) and in-hospital RASI (right graph).

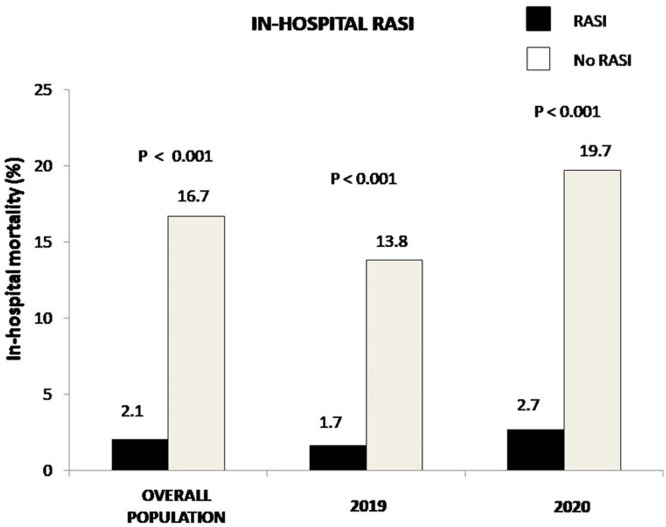

A further analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of in-hospital RASI therapy (data available in 5388 patients). Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. Patients receiving RASI during hospitalization were younger and more often males, more often diabetics (especially in 2019), active smokers, hypercholesterolemic, and had more often a family history of CAD and anterior STEMI; nevertheless, these patients less often presented with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock. Angiographic and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2S. Patients receiving RASI during hospitalization had more often radial access, LAD as culprit, postprocedural TIMI 3 flow, DAPT, while they displayed less often proximal lesion locations). In-hospital RASI therapy was associated with a significantly lower mortality (2.1% vs 16.7%, OR [95% CI] = 0.11 [0.084–0.14], p < 0.0001) ( Fig. 3). The benefits were confirmed in almost all the quartiles of the propensity score (Fig. 2S) and confirmed after the adjustment for all the confounding baseline characteristics, including the propensity score (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.15 [0.11–0.21], p < 0.001). In the analysis restricted to patients treated in 2020, we confirmed the survival benefits in mortality with in-hospital RASI therapy (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.15 [0.10–0.22], p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The prevalence of SARS-CoV2 infection (n = 62) was significantly lower among patients receiving RASI during hospitalization (1.7% vs 4.5%, OR [95% CI] = 0.37 [0.22–0.62], p < 0.001, adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.39 [0.23–0.66], p = 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics according to in-hospital RASI therapy.

| OVERALL POPULATION (N = 5388) |

YEAR 2019 (N = 2877) |

YEAR 2020 (N = 2511) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RASI (n = 4080) | No RASI (n = 1308) | P value | RASI (n = 2187) | No RASI 2019 (n = 680) | P value | RASI (n = 1883) | No RASI 2020 (n = 628) | P value | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 63 [55–72] | 66 [57–75] | < 0.001 | 63 [55–72] | 67 [57–75] | < 0.001 | 63 [54–71] | 65 [57–75] | < 0.001 |

| Age > 75 year – n. (%) | 795 (19.5) | 338 (25.8) | < 0.001 | 442 (20.1) | 177 (26) | 0.001 | 353 (18.7) | 161 (25.6) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender – n. (%) | 3047 (74.7) | 917 (70.1) | 0.001 | 1603 (73) | 482 (70.9) | 0.30 | 1444 (76.7) | 435 (69.3) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus- n (%) | 872 (21.4) | 310 (23.7) | 0.08 | 465 (21.2) | 176 (25.9) | 0.01 | 407 (21.6) | 134 (21.3) | 0.91 |

| Hypertension- n (%) | 2295 (53.6) | 700 (53.5) | 0.08 | 1256 (57.2) | 377 (55.4) | 0.45 | 1039 (55.2) | 323 (51.4) | 0.11 |

| Hypercholesterolemia - n (%) | 1799 (44.1) | 509 (38.9) | 0.001 | 957 (43.6) | 263 (38.7) | 0.03 | 842 (44.7) | 246 (39.2) | 0.02 |

| Active Smokers– n (%) | 1765 (43.3) | 507 (38.8) | 0.004 | 952 (43.3) | 259 (38.1) | 0.02 | 813 (43.2) | 248 (39.5) | 0.11 |

| Family History of CAD - n (%) | 961 (23.6) | 259 (19.8) | 0.005 | 519 (23.6) | 141 (20.7) | 0.13 | 442 (23.5) | 118 (18.8) | 0.02 |

| Previous STEMI- n (%) | 390 (9.6) | 108 (8.3) | 0.17 | 211 (9.6) | 51 (7.5) | 0.11 | 179 (9.5) | 57 (9.1) | 0.81 |

| Previous PCI – n (%) | 530 (13) | 138 (10.6) | 0.01 | 247 (12.5) | 81 (11.9) | 0.74 | 256 (13.6) | 57 [91] | 0.03 |

| Previous CABG - n (%) | 59 (1.4) | 29 (2.2) | 0.06 | 28 (1.3) | 14 (2.1) | 0.14 | 31 (1.6) | 15 (2.4) | 0.23 |

| Referral to Primary PCI Hospital | |||||||||

| Ambulance (from community) – n (%) | 2247 (55.1) | 682 (52.1) | 0.06 | 1169 (53.2) | 339 (44.9) | 0.14 | 1078 (52.7) | 343 (54.6) | 0.27 |

| Time delays | |||||||||

| Ischemia time, median [25–75th] | 195 [121–330] | 191 [125–330] | 0.76 | 190 [120–313] | 180 [120–289] | 0.18 | 200 [127–345] | 210 [130–380] | 0.36 |

| Total Ischemia time > 12 h – n (%) | 425 (10.4) | 127 (9.7) | 0.50 | 207 (9.4) | 53 (7.8) | 0.22 | 218 (11.6) | 74 (11.8) | 0.89 |

| Door-to-balloon time, median [25–75th] | 35 [25–60] | 40 [25–68] | < 0.001 | 35 [24–60] | 40 [25–68] | < 0.001 | 37 [25–60] | 40 [25–69] | 0.007 |

| Door-to-balloon time | |||||||||

| >30 min– n (%) | 2259 (55.4) | 816 (62.4) | < 0.001 | 1184 (53.9) | 424 (62.4) | < 0.001 | 1075 (57.1) | 392 (62.4) | 0.002 |

| Clinical Presentation | |||||||||

| Anterior STEMI– n (%) | 1922 (47.1) | 554 (42.2) | 0.003 | 1043 (47.5) | 287 (42.2) | 0.02 | 879 (46.7) | 267 (42.5) | 0.07 |

| Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest – n (%) | 226 (5.5) | 122 (9.3) | < 0.001 | 119 (5.4) | 55 (8.1) | 0.02 | 107 (5.7) | 67 (10.7) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock– n (%) | 223 (5.5) | 224 (17.1) | < 0.001 | 109 (5) | 106 (15.6) | < 0.001 | 114 (6.1) | 118 (18.8) | < 0.001 |

| Rescue PCI for failed thrombolysis – n (%) | 148 (3.6) | 48 (3.7) | 0.93 | 77 (3.5) | 26 (3.8) | 0.72 | 71 (3.8) | 22 (3.5) | 0.81 |

*Mann-Whitney test

CAD = Coronary Artery Disease; STEMI = ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; CABG 0 Coronary Artery Bypass Graft;

Fig. 3.

Bar graphs show in-hospital mortality in overall population, in 2019 and 2020 patients according to in-hospital RASI therapy.

Among the 62 SARSCoV-2 positive patients, both chronic RASI (OR [95% CI] = 1.95 [0.65–6.0], p = 0.23, adjusted OR [95% CI] = 1.41 [0.29–6.78], p = 0.67 or in-hospital RASI therapy (OR [95% CI] = 0.5 [0.16–1.56], p = 0.24; adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.9 [0.2–4.1], p = 0.89) had no significant negative effect on survival (Fig. 3S).

4. Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that among STEMI patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion during the COVID-19 pandemic, RASI therapy at admission had no negative impact on survival or the prevalence of SARSCoV-2 infection. In-hospital RASI therapy was even associated with a significantly lower mortality and less often with SARSCoV-2 infection. Finally, among SARSCoV-2 positive patients, both chronic RASI therapy before admission and in-hospital RASI did not have a significant negative impact on survival.

ACEI/ARB treatment has been studied in various cardiovascular disease and was found to be efficacious in reducing death and adverse cardiovascular end points [11], [12], [13], [14], with significant benefits observed among STEMI patients already at short-term follow-up, when the treatment was initiated within the first weeks after the event [15], [16].

However, insights from animal studies suggest that ACE2 inhibition might play a negative prognostic role of ACE2 inhibition in COVID-19 patients. In fact, the ACE2 enzyme is a cell membrane protein, that is used by the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter cells [2], [17]. Given the increased ACE2 expression in cardiovascular and renal systems shown in experimental studies with angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and an ACE inhibitor (ACEI), concerns have been raised that these drugs might augment the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of the coronavirus disease in patients with arterial hypertension and CVD, receiving these drugs [18], [19], [20].

The use of ACEI/ARBs in patients with COVID-19 is controversial in part due to the early reports from China, suggesting that COVID-19 patients with hypertension have worse outcomes [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. The analyses were crude and confounding factors were present that were also associated with hypertension, such as older age and cardiovascular disease. In patients with cardiovascular disease, COVID-19 is associated with substantial mortality, and clarification of confounding by disease or indication is crucial. In fact, several additional studies have shown no harmful effects or even beneficial effects from RASI therapy [6], [7], [8].

Mangia et al. [26] carried out a population-based case–control study in the Lombardy region of Italy. A total of 6272 case patients in whom infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was confirmed between February 21 and March 11, 2020, were matched with 30,759 beneficiaries of the Regional Health Service (controls) according to sex, age, and municipality of residence. Due to the higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease, the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs was more frequent among patients with COVID-19 than among control subjects. However, there was no evidence that ACE inhibitors or ARBs affected the risk of COVID-19. Li et al. [6] examined a case series from hospitals in Wuhan, China, and found no association between RASI and COVID-19. Similar results have been described from North America [10], [11]. Reynolds et al. [27] studied patients with COVID-19 and hypertension and found no significant difference in COVID-19 outcomes with RASI use as compared to other antihypertensive drugs. The results have been confirmed in population studies conducted in Spain [7] and Denmark [8]. In both analyses, RASI were associated with higher mortality that disappeared after adjustment for confounding factors. The authors concluded that the prior use of ACEI/ARBs was not significantly associated with COVID-19 diagnosis among patients with hypertension or with mortality or severe disease among patients diagnosed as having COVID-19. The absence of any harmful effect of ACE-Inhibitors has been recently confirmed in several meta-analysis [28], [29].

However, so far, no data have been reported in patients with an acute STEMI, representing a population with a very high adverse event risk and guideline-recommended RASI use in the majority of patients.

Our report is the first study focused on STEMI patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion, including more than 6000 patients treated with primary PCI. We found that chronic RASI at admission did not affect the prevalence of SARSCoV2 infection and was associated with lower mortality and cardiogenic shock at presentation. Furthermore, in-hospital RASI therapy was associated with a significantly lower mortality, and a lower prevalence of SARSCoV2 infection, but showed no significant relationship with the survival of infected patients. Therefore, the present study confirms the overall mortality benefit of RASI in patients with STEMI, and additionally it does not suggest a link between RASI therapy and COVID-19 susceptibility or subsequent worse outcomes in case of COVID-19 infection.

Professional societies have issued position statements that ACEI/ARBs should not be discontinued [5], statements that this study supports. Several randomized studies have been initiated in various settings of COVID-19 (hospitalized and outpatient) and for both ACEIs and ARBs as well [30], [31]. In the recent randomized BRACE-CORONA Trial [32], 659 patients with chronic RASI therapy at admission and confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 were randomly assigned to a temporary 30-day suspension or continuation of RASI therapy. A similar 30-day mortality (2.8% vs 2.7%) was observed between the two groups. Waiting for the results of further randomized trials, that will definitively provide information on the harmful or beneficial effects on the occurrence of COVID and its mortality rates, RASI therapy should still be prescribed and not interrupted, especially among patients suffering from hypertension, heart failure or STEMI, clinical settings in which the greatest benefits in outcome may be expected.

5. Limitations

This study, which assessed data from 77 high-volume European primary PCI centers, is limited by its retrospective, non-randomized design. As it may be expected, patients on RASI therapy differed from the other patients in age and some comorbidities, and displayed a more composite cardiovascular history, with potential negative impact on the prognosis. Nevertheless, these patients could also have been the ones with previous regular hospital visits and with good compliance to medication. However, since we included an all-comers population, we expect a balancing between these two opposite potential biases and moreover we adjusted the findings for all known confounding factors. Furthermore, our research was conducted during a pandemic emergency, which was a challenge and expected to encounter some missing data. Nevertheless, considering all adversities, the proportion of patients with missing data regarding in-hospital RASI therapy was acceptable. As we did not collect information on the type and dosage of RASI, we cannot perform a further in-depth assessment of prognostic implications. Although in 2019 and 2020 similar rates of RASI prescription were observed, we cannot exclude that during hospitalization RASI might have been less often prescribed among patients with (actual or presumed) SARS-CoV2 positivity, because of the fear of a potential negative impact of RASI on surviving COVID-19. In fact, even though the results of the molecular swab were generally available only after PCI, therefore not affecting procedural indications, such information could have, instead, potentially conditioned the RASI prescription after the intervention. Therefore, the present report provides a real-life picture of the management of STEMI patients during the pandemic. In addition, acute kidney failure, heart failure, and hypotension might have represented severe comorbidities, preventing the introduction of RASI therapy during hospitalization and negatively affecting the prognosis. Unfortunately, these data were not routinely collected and are, therefore, not available. However, these factors could have biased the evaluation of the prognostic implications of initiation of RASI therapy during hospitalization rather than the prognostic impact chronic RASI at admission, that represented our main primary analysis. In addition, although our database comprised almost 5400 STEMI patients with known in-hospital pharmacological therapy and clinical outcome following mechanical reperfusion therapy, the evaluation of the prognostic impact of RASI therapy among SARS-CoV2-positive patients was limited due to the relatively low prevalence of the infection, and neither we could evaluate the incidence of respiratory complications in these patients.

Finally, we included only patients undergoing primary PCI, excluding those who died before hospital admission or prior to angiography, and STEMI patients managed conservatively. Therefore, caution should be exercised in the interpretation the prognostic implications of our results.

6. Conclusions

This is the first study investigating the prognostic impact of RASI therapy in STEMI patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion during COVID-19 pandemic. We found that chronic RASI therapy at admission and RASI therapy during hospitalization were associated with a significant reduction in mortality, without any negative effect on SARSCoV2 infection or survival among SARSCoV2 positive patients. Therefore, waiting for future randomized trials, RASI should not be suspended or omitted, unless contraindicated, among STEMI patients undergoing mechanical reperfusion, even in case of SARSCoV2 infection.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

All authors contributed to the collection of data and final approval of the manuscript. Giuseppe DeLuca and Monica Verdoia contributed to the analysis of the data and manuscript editing, Giuliana Cortese and Giuseppe De Luca to the statistical analysis.

Acknowledgments

The study was promoted and partially funded by the Aging Project- Department of Excellence, Department of Translational Medicine, Eastern Piedmont University, Novara, Italy.

The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents. The authors declare no conflict of interest with the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K.S.M., Lau E.H.Y., Wong J.Y., Xing X., Xiang N., Wu Y., Li C., Chen Q., Li D., Liu T., Zhao J., Liu M., Tu W., Chen C., Jin L., Yang R., Wang Q., Zhou S., Wang R., Liu H., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shao G., Li H., Tao Z., Yang Y., Deng Z., Liu B., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Shi G., Lam T.T.Y., Wu J.T., Gao G.F., Cowling B.J., Yang B., Leung G.M., Feng Z. Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, china, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. Mar 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaduganathan M., Vardeny O., Michel T., McMurray J.J.V., Pfeffer M.A., Solomon S.D. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(17):1653–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.https://professional.heart.org/professional/ScienceNews/UCM_505836_HFSAACCAHA-statement-addresses-concerns-re-using-RAAS-antagonists-in-COVID-19.jsp.

- 5.European Society of Cardiology. Position statement of the ESC council on hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. Published March 13, 2020. (Accessed 12 June 2020). https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang.

- 6.Li J., Wang X., Chen J., Zhang H., Deng A. Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):1–6. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1624. Apr 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Abajo F.J., Rodríguez-Martín S., Lerma V., Mejía-Abril G., Aguilar M., García-Luque A., Laredo L., Laosa O., Centeno-Soto G.A., Ángeles Gálvez M., Puerro M., González-Rojano E., Pedraza L., de Pablo I., Abad-Santos F., Rodríguez-Mañas L., Gil M., Tobías A., Rodríguez-Miguel A., Rodríguez-Puyol D. MED-ACE2-COVID19 study group.Use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1705–1714. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8. May 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fosbøl E.L., Butt J.H., Østergaard L., Andersson C., Selmer C., Kragholm K., Schou M., Phelps M., Gislason G.H., Gerds T.A., Torp-Pedersen C., Køber L. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. JAMA. 2020;324(2):168–177. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11301. Jun 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Luca G., Suryapranata H., Ottervanger J.P., van ’t Hof A.W., Hoorntje J.C., Gosselink A.T., Dambrink J.H., de Boer M.J. Impact of statin therapy at discharge on 1-year mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(1):186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanley J.A., McNeil B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox K.M. EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease Investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study) Lancet. 2003;362:782–788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braunwald E., Domanski M.J., Fowler S.E., Geller N.L., Gersh B.J., Hsia J., Pfeffer M.A., Rice M.M., Rosenberg Y.D., Rouleau J.L. PEACE trial investigators. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2058–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfeffer M.A., Braunwald E., Moye L.A., Basta L., Brown E.J.Jr, Cuddy T.E., Davis B.R., Geltman E.M., Goldman S., Flaker G.C., Klein M., Lamas G.A., Packer M., Rouleau J., Rouleau J.L., Rutherford J., Wertheimer J.H., Hawkins M. Effect of Captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction: results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. New Engl. J. Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. 669–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flather M.D., Yusuf S., Kober L., Pfeffer M., Hall A., Murray G., Torp-Pedersen C., Ball S., Pogue J., Moye L., Braunwald E. Long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy in patients with heart failure or left-ventricular dysfunction: a systematic overview of data from individual patients. ACE-inhibitor myocardial infarction collaborative group. Lancet. 2000;355:1575–1581. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ambrosioni E., Borghi C., Magnani B. The effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor zofenopril on mortality and morbidity after anterior myocardial infarction. The survival of myocardial infarction long-term evaluation (SMILE) study investigators. New Engl. J. Med. 1995;332(2):80–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501123320203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Indications for ACE inhibitors in the early treatment of acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview of individual data from 100,000 patients in randomized trials. ACE Inhibitor Myocardial Infarction Collaborative Group. Circulation. 1998 Jun 9;97(22):2202–2212. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181(2):281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agata J., Ura N., Yoshida H., Shinshi Y., Sasaki H., Hyakkoku M., TANIGUCHI S., SHIMAMOTO K. Olmesartan is an angiotensin II receptor blocker with an inhibitory effect on angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertens. Res. 2006;29:865–874. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X., Ye Y., Gong H., Wu J., Yuan, Wang S., Yin P., Ding Z., Kang L., Jiang Q., Zhang W., Li Y., Ge J., Zou J Y. The effects of different angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers on the regulation of the ACE-AngII-AT1 and ACE2-Ang(1-7)-Mas axes in pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling in male mice. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M Y., Wu X., Zhang L., He T., Wang H., Wan J., Wang X., Lu Z. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie J., Tong Z., Guan X., Du B., Qiu H. Clinical characteristics of patients who died of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., Ji R., Wang H., Wang Y., Zhou Y. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H., Wu Y., Zhang L., Yu Z., Fang M., Yu T., Wang Y., Pan S., Zou X., Yuan S., Shang Y. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao C., Cai Y., Zhang K., Zhou L., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Li Q., Li W., Yang S., Zhao X., Zhao Y., Wang H., Liu Y., Yin Z., Zhang R., Wang R., Yang M., Hui C., Wijns W., McEvoy J.W., Soliman O., Onuma Y., Serruys P.W., Tao L., Li F. Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID-19 mortality: a retrospective observational study. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41(22):2058–2066. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mancia G., Rea F., Ludergnani M., Apolone G., Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of COVID-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(25):2431–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006923. Jun 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds H.R., Adhikari S., Pulgarin C., Troxel A.B., Iturrate E., Johnson S.B., Hausvater A., Newman J.D., Berger J.S., Bangalore S., Katz S.D., Fishman G.I., Kunichoff D., Chen Y., Ogedegbe G., Hochman J.S. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(25):2441–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008975. Jun 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grover A., Oberoi M. A systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flacco ME, Acuti Martellucci C., Bravi F., Parruti G., Cappadona R., Mascitelli A., Manfredini R., Mantovani LG, Manzoli L. Treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs and risk of severe/lethal COVID-19: a meta-analysis.Heart. 2020 Jul 1:heartjnl-2020–317336. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020–317336. Online ahead of print.PMID: 32611676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Lopes R.D., Macedo A.V.S., de Barros E., Silva P.G.M., Moll-Bernardes R.J., Feldman A., D’Andréa Saba Arruda G., de Souza A.S., de Albuquerque D.C., Mazza L., Santos M.F., Salvador N.Z., Gibson C.M., Granger C.B., Alexander J.H., de Souza O.F. BRACE CORONA investigators. Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: impact on adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The BRACE CORONA Trial. Am. Heart J. 2020;226:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stopping ACE-inhibitors in COVID-19 (ACEI-COVID).https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/ show/NCT04353596?term=Ace-inhibitor&draw=2& rank =1.

- 32.Brace Corona Trial. https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/LOPES.