Abstract

Aims

Although catheter ablation has emerged as an important therapy for patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF), there are limited data on sex-based differences in outcomes. We sought to compare in-hospital outcomes and 30-day readmissions of women and men undergoing AF ablation.

Methods and results

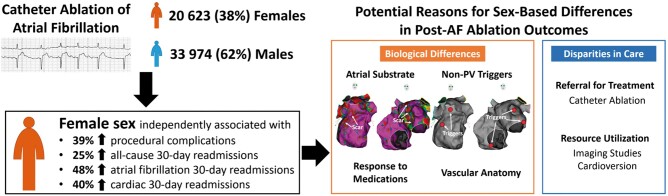

Using the United States Nationwide Readmissions Database, we analysed patients undergoing AF ablation between 2010 and 2014. Based on ICD-9-CM codes, we identified co-morbidities and outcomes. Multivariable logistic regression and inverse probability-weighting analysis were performed to assess female sex as a predictor of endpoints. Of 54 597 study patients, 20 623 (37.7%) were female. After adjustment for age, co-morbidities, and hospital factors, women had higher rates of any complication [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.39; P < 0.0001], cardiac perforation (aOR 1.39; P = 0.006), and bleeding/vascular complications (aOR 1.49; P < 0.0001). Thirty-day all-cause readmission rates were higher for women compared to men (13.4% vs. 9.4%; P < 0.0001). Female sex was independently associated with readmission for AF/atrial tachycardia (aOR 1.48; P < 0.0001), cardiac causes (aOR 1.40; P < 0.0001), and all causes (aOR 1.25; P < 0.0001). Similar findings were confirmed with inverse probability-weighting analysis. Despite increased complications and readmissions, total costs for AF ablation were lower for women than men due to decreased resource utilization.

Conclusions

Independent of age, co-morbidities, and hospital factors, women have higher rates of complications and readmissions following AF ablation. Sex-based differences and disparities in the management of AF need to be explored to address these gaps in outcomes.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Sex, Readmission, Mortality, Outcomes research

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia worldwide. Although the age-adjusted incidence of AF is estimated to be 1.5 to 2 times higher in men than in women,1 the prevalence of women with AF exceeds that of men due to increased longevity.2 Recent studies have identified significant sex-based differences and disparities with respect to the clinical presentation and treatment of AF. Women with AF have more symptoms and worse quality of life compared to men with AF.3 Women are older at the time of presentation and are more likely to seek medical attention due to symptoms from AF.4

Yet, despite the well-established role of pulmonary vein (PV) isolation for the treatment of symptomatic AF,5 women are less likely than men to be referred for catheter ablation.6 , 7 Studies examining sex-based outcomes after AF ablation have yielded conflicting results.8 Currently, there are limited contemporary population-based data on differences in AF ablation outcomes between females and males. Therefore, using the all-payer, nationally representative Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD), we sought to compare sex-based outcomes, 30-day readmissions, and costs following catheter ablation of AF.

Methods

A detailed description of the methods used in this study is in the Supplementary material online. Briefly, data were obtained from the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) NRD, which is a publicly available research database designed to allow nationally representative readmission analyses. Data from the NRD between 2010 and 2014 were analysed. Each admission record in the NRD contains information on patient diagnoses and procedures performed based on International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. All hospitalizations for catheter ablation of AF were selected by searching for admissions with a primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for AF (427.31) and for catheter ablation (37.34). Any admission with a secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for other arrhythmias or a procedure code for device implantation was excluded (Supplementary material online, Table S1). Patient-level variables, hospital-level variables, and cardiac diagnoses were defined using ICD-9-CM codes, Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) codes, or AHRQ comorbidity measures as defined in Supplementary material online, Table S2. All study endpoints were compared with respect to sex. The primary endpoint of this study was 30-day all-cause readmission and secondary endpoints were in-hospital mortality, procedural complications, and cost. Primary causes of 30-day readmissions were identified using primary CCS and ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (Supplementary material online, Table S3).

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). Categorical variables were shown as frequencies and continuous variables were presented as mean or median. Baseline characteristics were compared by the Rao-Scott χ2 test for categorical variables and either survey-specific linear regression or the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon non-parametric test for continuous variables. To identify the association of female sex and endpoints, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models by including covariates that were associated with outcomes of interest in univariate analysis (P < 0.10). In addition, we performed inverse probability-weighting to account for imbalances in patient-level and hospital-level characteristics between female and male patients. Cumulative incidence curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by using the log-rank statistic. Cumulative cost was defined as cost of 30-day readmission plus cost of index admission. For patients who were not readmitted, cumulative cost was equivalent to cost of index admission. To examine factors associated with cumulative cost, multivariable linear regression of log transformation of costs was performed. All tests were two-sided with P-values <0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics of females and males undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation

The NRD database included 181 545 078 admissions between 2010 and 2014. Of these, 54 597 admissions for catheter ablation of AF were identified with women accounting for 37.7% of the study population (Table 1). There was a 4.3% increase in the proportion of females undergoing AF ablation, from 37.2% in 2010 to 38.8% in 2014 (P-for-trend = 0.014). Compared to men, women were older and had an increased prevalence of congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, anaemia, and valvular heart disease. Women were less likely to have coronary artery disease and history of smoking, alcohol abuse, and substance abuse. Overall, women had a higher burden of co-morbidities (18.0% vs. 11.0% with Elixhauser co-morbidity score > 4; P < 0.0001). Females resided in lower household income neighbourhood by zip code and underwent ablation at more non-teaching and low AF ablation volume hospitals. Compared to males, females had longer index hospitalization stays but had lower index admission hospitalization costs.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and hospital characteristics for all patients and patients stratifed by sex undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation 2010–14

| Characteristics | Overall | Female | Male | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of admissions | 54 597 | 20 623 | 33 974 | |

| Age, mean (SE), years | 64.3 (0.15) | 67.9 (0.16) | 62.2 (0.16) | <0.0001 |

| Age group | <0.0001 | |||

| <65 | 25 572 (46.8) | 6991 (33.9) | 18 580 (54.7) | |

| 65–74 | 19 422 (35.6) | 8074 (39.1) | 11 348 (33.4) | |

| 75- | 9603 (17.6) | 5558 (26.9) | 4046 (11.9) | |

| History of CHF | 9295 (17.0) | 3960 (19.2) | 5335 (15.7) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 14 432 (26.4) | 4499 (21.8) | 9933 (29.2) | <0.0001 |

| Prior PCI | 4311 (7.9) | 1217 (5.9) | 3094 (9.1) | <0.0001 |

| Prior CABG | 3054 (5.6) | 684 (3.3) | 2370 (7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Prior PPM | 6432 (11.8) | 3768 (18.2) | 2664 (7.8) | <0.0001 |

| Prior ICD | 2835 (5.2) | 761 (3.7) | 2074 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 31 704 (58.1) | 12 459 (60.4) | 19 245 (56.6) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 077 (20.3) | 4223 (20.5) | 6854 (20.2) | 0.5945 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 24 489 (44.9) | 9083 (44.0) | 15 406 (45.3) | 0.0954 |

| Obesity | 8641 (15.8) | 3470 (16.8) | 5171 (15.2) | 0.0058 |

| History of stroke | 3303 (6.0) | 1597 (7.7) | 1706 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease | 7321 (13.4) | 3420 (16.6) | 3900 (11.5) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1847 (3.4) | 712 (3.5) | 1135 (3.3) | 0.6860 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1643 (3.0) | 1031 (5.0) | 612 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 8163 (15.0) | 3925 (19.0) | 4237 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking | 2784 (5.1) | 785 (3.8) | 1999 (5.9) | <0.0001 |

| Renal disease | 3880 (7.1) | 1465 (7.1) | 2416 (7.1) | 0.9830 |

| Alcohol abuse | 647 (1.2) | 82 (0.15) | 565 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Substance abuse | 211 (0.4) | 20 (0.1) | 191 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 572 (1.0) | 223 (1.1) | 348 (1.0) | 0.7140 |

| Anemia | 3177 (5.8) | 1832 (8.9) | 1346 (4.0) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1040 (1.9) | 390 (1.9) | 650 (1.9) | 0.9152 |

| Elixhauser co-morbidity score | <0.0001 | |||

| ≤4 | 47 150 (86.4) | 16 902 (82.0) | 30 248 (89.0) | |

| >4 | 7447 (13.6) | 3721 (18.0) | 3726 (11.0) | |

| Hospital AF ablation volume | <0.0001 | |||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 931 (1.7) | 488 (2.4) | 443 (1.3) | |

| 2nd quartile | 3704 (6.8) | 1610 (7.8) | 2095 (6.2) | |

| 3rd quartile | 9705 (17.8) | 3858 (18.7) | 5847 (17.2) | |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 40 257 (73.7) | 14 667 (71.1) | 25 590 (75.3) | |

| Elective procedure | 37 557 (68.8) | 13 603 (66.0) | 23 953 (70.5) | <0.0001 |

| Median household income | <0.0001 | |||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 10 523 (19.6) | 4538 (22.3) | 5985 (17.9) | |

| 2nd quartile | 12 667 (23.6) | 5172 (25.5) | 7495 (22.5) | |

| 3rd quartile | 14 234 (26.5) | 5202 (25.6) | 9032 (27.1) | |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 16 245 (30.3) | 5404 (26.6) | 10 841 (32.5) | |

| Primary payer | <0.0001 | |||

| Medicare | 28 852 (52.9) | 13 671 (66.3) | 15 180 (44.7) | |

| Medicaid | 1605 (2.9) | 587 (2.8) | 1018 (3.0) | |

| Private including HMO | 22 363 (41.0) | 5911 (28.7) | 16 451 (48.4) | |

| Self-pay/no charge/other | 1757 (3.2) | 448 (2.3) | 1310 (3.9) | |

| Hospital location | 0.0407 | |||

| Urban | 54 026 (99.0) | 20 365 (98.7) | 33 661 (99.1) | |

| Rural | 571 (1.0) | 259 (1.3) | 312 (0.9) | |

| Hospital type | 0.009 | |||

| Teaching | 40 571 (74.3) | 15 056 (73.0) | 25 515 (75.1) | |

| Non-teaching | 14 026 (25.7) | 5568 (27.0) | 8459 (24.9) | |

| Hospital bed size | 0.6784 | |||

| Small | 1892 (3.5) | 735 (3.6) | 1157 (3.4) | |

| Medium | 9471 (17.3) | 3514 (17.0) | 5957 (17.5) | |

| Large | 43 234 (79.2) | 16 374 (79.4) | 26 860 (79.1) | |

| Length of index hospital stay, mean (SE) [median], days | 2.4 (0.04) [1.0; 1.0–2.4] | 2.8 (0.05) [1.2; 1.0–2.8] | 2.2 (0.04) [1.0; 1.0–2.0] | <0.0001 |

| Prolonged index hospital stay | 15 770 (28.9) | 7121 (34.5) | 8649 (25.5) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay, days ≥ 3 | ||||

| Cost of index hospitalization, mean (SE) [median], $ | 24 188 (398.5) [22 922; 16 189–29 839] | 23 466 (371.9) [22 334; 15 256–29 538] | 24 628 (440.2) [23 299; 16 831–30 043] | <0.0001 |

| Index hospitalization disposition | <0.0001 | |||

| Home | 53 350 (97.7) | 19 918 (96.6) | 33 432 (98.4) | |

| Facilitya | 1107 (2.0) | 661 (3.2) | 445 (1.3) | |

| AMA/unknown | 54 (0.1) | 14 (0.07) | 40 (0.12) | |

| Died | 86 (0.2) | 30 (0.14) | 56 (0.17) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMA, against medical advice; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; HMO, health maintenance organization; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker; SE standard error.

Facility indicates skilled nursing facility, intermediate care facility, and inpatient rehabilitation facility.

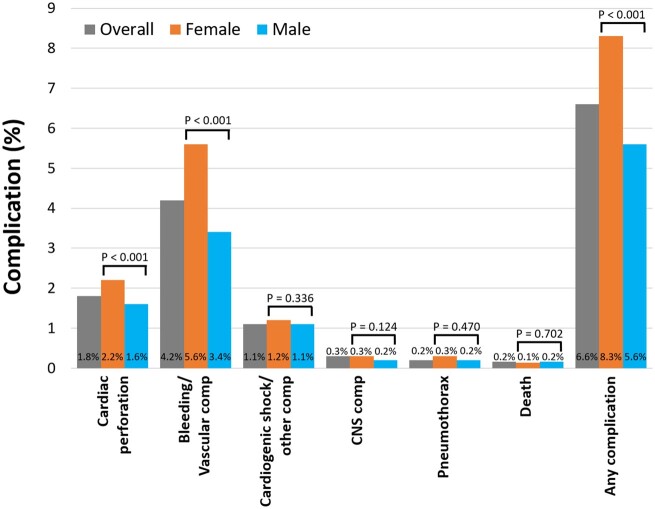

Complications during index hospitalization for atrial fibrillation ablation in females and males

The median length of stay during the index admission for AF ablation was 1.0 (interquartile range [IQR] 1.0–2.4) days. The overall rate of in-hospital mortality was 0.16% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12–0.19%] and of any complication was 6.6% (95% CI 6.4–6.8%). Unadjusted rates of specific complications associated with AF ablation for the overall study population and stratified by sex are shown in Figure 1. Women had similar in-hospital mortality rates compared to men but higher rates of any complication (8.3% vs. 5.6%; P < 0.0001). Univariate and multivariable risk factors of the occurrence of any complication are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for clinical and hospital characteristics, female sex was independently associated with AF ablation-associated complications with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.39 (95% CI 1.23–1.58; P < 0.0001). Furthermore, female sex was associated with increased cardiac perforation [aOR 1.39 (95% CI 1.10–1.76; P = 0.006)] and bleeding/vascular complications, [aOR 1.49 (95% CI 1.28–1.73; P < 0.0001)] (Table 3). Using inverse probability-weighting analysis, female sex was also found to be associated with increased risk of death/any complication, cardiac perforation, and bleeding/vascular complications. In subgroup analysis with multivariable logistic regression models, female sex was independently associated with increased complications regardless of age < 65 years vs. age ≥ 65 years (Supplementary material online, Table S4). Compared to patients without prior heart failure, the impact of female sex on complications in the subgroup of patients with heart failure was attenuated.

Figure 1.

Rates of complications and mortality during index admission for atrial fibrillation ablation for the overall study population and stratified by sex. CNS, central nervous system; Comp, complication.

Table 2.

Predictors of combined mortality/any complication associated with atrial fibrillation ablation

| Univariate |

Multivariable |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Unadjusted OR | P-value | Adjusted OR | P-value |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||

| Female | 1.51 (1.34–1.70) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 1.40 (1.20–1.64) | <0.0001 | 1.34 (1.14–1.58) | 0.0004 |

| Anemia | 2.67 (2.20–3.23) | <0.0001 | 2.09 (1.71–2.55) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 3.85 (2.89–5.14) | <0.0001 | 3.22 (2.34–4.41) | <0.0001 |

| Hospital AF ablation volume | ||||

| 1st quartile | 1.54 (1.12–2.11) | 0.007 | 1.48 (1.04–2.08) | 0.027 |

| 2nd quartile | 1.74 (1.43–2.13) | <0.0001 | 1.76 (1.41–2.19) | <0.0001 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.53 (1.31–1.79) | <0.0001 | 1.51 (1.28–1.77) | <0.0001 |

| 4th quartile | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||

| Age | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.0006 | ||

| CHF | 1.36 (1.18–1.57) | <0.0001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 (1.07–1.43) | 0.004 | ||

| History of stroke | 1.27 (1.03–1.58) | 0.028 | ||

| Valvular disease | 1.26 (1.07–1.49) | 0.005 | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1.35 (1.02–1.80) | 0.037 | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | 0.013 | ||

| Smoking | 0.79 (0.61–1.03) | 0.083 | ||

| Chronic renal disease | 1.70 (1.40–2.05) | <0.0001 | ||

| Teaching hospital | 1.18 (0.98–1.43) | 0.076 | ||

| Primary payer | ||||

| Medicare | 1 (Ref) | |||

| Medicaid | 0.86 (0.65–1.15) | 0.312 | ||

| Private includingHMO | 0.82 (0.72–0.94) | 0.005 | ||

| Self-pay/no charge/other | 0.97 (0.66–1.43) | 0.881 | ||

Among the 54 597 estimated admissions, there were 3613 (6.6%) combined mortality/any complication events analysed in the logistic regression model.

AF, atrial fibrillation; AMA, against medical advice; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; HMO, health maintenance organization; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPM, permanent pacemaker; SE standard error.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for procedural complications based on female sex (male as reference)

| Event rates (%) |

Logistic regression analysis |

Inverse probability weighting analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Female | Male | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Cardiac perforation/effusion/tamponade | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.44 (1.16–1.78) | 0.0011 | 1.39 (1.10–1.76) | 0.006 | 1.36 (1.06–1.75) | 0.015 |

| Bleeding/vascular complications | 5.6 | 3.4 | 1.67 (1.45–1.92) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.28–1.73) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.24–1.71) | <0.0001 |

| CNS complication | 0.34 | 0.23 | 1.48 (0.91–2.39) | 0.114 | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) | 0.497 | 1.22 (0.67–2.22) | 0.526 |

| Pneumothorax | 0.26 | 0.20 | 1.28 (0.65–2.54) | 0.476 | 1.08 (0.54–2.15) | 0.838 | 1.14 (0.50–2.60) | 0.750 |

| Other cardiac complication /cardiogenic shock/arrest | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.17 (0.86–1.58) | 0.314 | 1.16 (0.84–1.60) | 0.364 | 1.16 (0.83–1.61) | 0.395 |

| Death | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.87 (0.42–1.80) | 0.697 | 0.64 (0.33–1.23) | 0.180 | 0.56 (0.28–1.11) | 0.099 |

| Any complication | 8.3 | 5.6 | 1.51 (1.34–1.70) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) | <0.0001 | 1.35 (1.18–1.54) | <0.0001 |

CNS, central nervous system; OR, odds ratio.

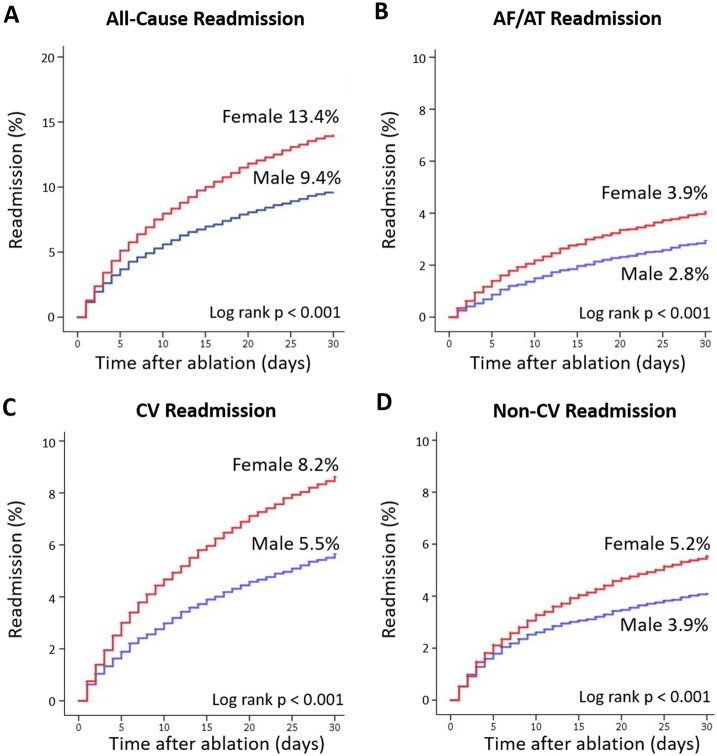

Thirty-day readmissions after atrial fibrillation ablation in females and males

Among 54 411 patients who survived to discharge following AF ablation, the 30-day all-cause readmission rate was 10.9% (95% CI 10.7–11.2%). Readmission rates were significantly higher for women compared to men (13.4% vs. 9.4%; P < 0.0001). Median length of hospitalization during readmission was 2.5 (IQR 1.2–4.5) days with an in-hospital mortality rate of 2.2% (95% CI 1.9–2.6%). The leading causes of in-hospital mortality during readmission were congestive heart failure (14%), pneumonia (11.9%), sepsis (10.8%), acute respiratory failure (7.9%), and cardiac arrest (5.6%). Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by presence and absence of 30-day readmission are shown in Supplementary material online, Table S5. Patient readmitted following discharge from AF ablation were more likely to be female and to have co-morbidities. The univariate and multivariable risk factors of 30-day all-cause readmission after initial hospitalization for AF ablation are listed in Supplementary material online, Table S6. Female sex was associated with a 25% increased risk of all-cause readmission after AF ablation [aOR 1.25 (95% CI: 1.14–1.39); P < 0.0001].

Timing and causes of 30-day readmission in females and males

The distribution of time to readmission following discharge from the index hospitalization for AF ablation stratified by sex is shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S1. The median time to 30-day readmission for women and men were similar (P = 0.325). Overall, cardiac causes and non-cardiac causes accounted for 59% and 41% of all 30-day readmissions, respectively (Supplementary material online, Figure S2). Specifically, AF/atrial tachycardia (AT) and congestive heart failure accounted for 29% and 13% of all readmissions. The leading categories of non-cardiac readmissions were infectious (8.4%), gastrointestinal (5.3%), and vascular (4.7%). Hazard curves for all-cause, AF/AT, cardiac and non-cardiac 30-day readmissions stratified by sex are shown in Figure 2A–D. Using multivariable logistic regression analysis and inverse probability weighting analysis, female sex was associated with an increased risk of 30-day all-cause, AF/AT, and cardiac readmissions (Table 4). In subgroup analysis, female sex was independently associated with all-cause readmission regardless of age < 65 years vs. age ≥ 65 years and of history of prior CHF vs. no CHF (Supplementary material online, Table S7).

Figure 2.

Hazard curves for 30-day readmission stratified by sex. (A) All-cause readmission. (B) Atrial fibrillation/tachycardia readmission. (C) Cardiac readmission. (D) Non-cardiac readmission. AF, atrial fibrillation; AT, atrial tachycardia; CV, cardiac; Non-CV, non-cardiac.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for all-cause, atrial fibrillation/tachycardia, cardiac, and non-cardiac 30-day readmissions based on female sex (male as reference)

| Event rates (%) |

Logistic regression analysis |

Inverse probability weighting analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Female | Male | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| All-cause readmission | 13.4 | 9.4 | 1.49 (1.36–1.63) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.14–1.39) | <0.0001 | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) | <0.0001 |

| AF/AT readmission | 3.9 | 2.8 | 1.44 (1.23–1.68) | <0.0001 | 1.48 (1.25–1.75) | <0.0001 | 1.39 (1.17–1.66) | 0.0002 |

| Cardiac readmission | 8.2 | 5.5 | 1.54 (1.38–1.73) | <0.0001 | 1.40 (1.23–1.58) | <0.0001 | 1.36 (1.18–1.55) | <0.0001 |

| Non-cardiac readmission | 5.2 | 3.9 | 1.34 (1.17–1.54) | <0.0001 | 1.08 (0.92–1.25) | 0.349 | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 0.368 |

AF/AT, atrial fibrillation/tachycardia; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Total costs of atrial fibrillation ablation in females and males

Compared to males, median index hospitalization costs for AF ablation were significantly lower for females [$22 334 (IQR $15 256–$29 538) vs. $23 299 (IQR $16 831–$30 043); P < 0.0001]. During index hospitalization, women were significantly less likely to undergo transthoracic/transoesophageal echocardiography, intracardiac echocardiography, cardioversions, and unspecified cardiac diagnostic procedures (Supplementary material online, Table S8). Among patients readmitted within 30 days, the median costs of readmission trended higher for females compared to males [$5774 (IQR $3286–$10 661) vs. $5519 (IQR $3263–$10 071); P = 0.076]. During readmissions, females were more likely to undergo blood transfusions and thoracentesis but had similar rates of cardiac procedures as males (Supplementary material online, Table S9). Overall, cumulative (index plus readmission) hospitalization costs for females after AF ablation were significantly less at $23 111 (IQR $15 924–$30 583) vs. $23 819 (IQR $17 269–$30 874) (P < 0.001), respectively. After adjustment for predictors of hospitalization costs including readmission, co-morbidities, and hospital factors, female sex was associated with a small, although statistically significant, 2.4% decrease in cumulative hospitalization costs (95% CI −0.042 to −0.007; P = 0.0067).

Discussion

In this analysis of a real-world, all-payer, nationally representative NRD from the United States which included >54 000 index admission records between 2010 and 2014, we identified significant differences in the characteristics and outcomes between females and males following catheter ablation of AF. First, compared to males, females undergoing AF ablation were older and had more co-morbidities. Second, even after adjusting for age, co-morbidities, and hospital factors, women had more procedural complications. Third, adjusted 30-day readmission rates for all causes, recurrent AF/AT, and cardiac causes following AF ablation were 25%, 48%, and 40% higher for females compared to males, respectively. Finally, surprisingly, despite higher rates of complications and readmissions, total cumulative costs for AF ablation were lower for women, which may have been due to decreased resource utilization. To our knowledge, this is the largest study based on an all-payer, nationally representative population to examine the impact of female sex on AF ablation outcomes and cost.

Consistent with findings from other studies, females undergoing AF ablation in our study were older and had more co-morbidities.9–11 A critical finding of our study is that the increased rate of complications among women undergoing AF ablation cannot be explained by age and co-morbidity burden alone. Previous studies have shown increased unadjusted rates of tamponade and bleeding among women following AF ablation.11–13 To address confounding, we adjusted for age and co-morbidities using both multivariable logistic regression and inverse probability-weighting analysis and found that female sex was an independent and strong risk factor for complications following ablation. Therefore, female-specific biologic factors that increase the risk of complications are likely at play. Differences in left atrial size, geometry, and substrate among women may increase the risks of perforation during transseptal puncture and catheter manipulation and of steam pops during radiofrequency ablation energy delivery. Increased vascular and bleeding complications among women have been consistently described in the percutaneous coronary intervention and acute coronary syndrome literature.14 , 15 Sex-based variations in body size, vascular anatomy, and anticoagulation response may account for increased rates of bleeding in women.

Furthermore, female sex is a strong predictor of 30-day all-cause, AF/AT, and cardiac readmissions. Although previous single centre studies revealed similar AF ablation success rates between women and men,16 , 17 our study supports more recent data that demonstrate higher rates of recurrent AF among women. Patel et al.10 identified unadjusted AF recurrence rates of 32% in women and 23% in men. A study based on administrative claims data obtained largely from private payers on AF ablations performed between 2007 and 2011 identified a modest 12% increase in the rate of AF readmissions among women.11 In comparison, we found a 48% increase in AF readmissions among women. Because the NRD is an all-payer, nationally representative database, our study population was older, as >50% of our cohort had Medicare insurance. Our findings are consistent with those of a recent sub-analysis of the FIRE and ICE trial, which found that female sex was independently associated with a 37% increase in recurrent AF post-ablation.18

The potential reasons for increased AF readmissions among women are myriad. First, women are often referred for ablation at a later time during their course of AF, which translates to a higher prevalence of non-paroxysmal AF10 and co-morbidities which are associated with more AF recurrences. Second, several studies have shown an increased rate of non-PV triggers among women,10 , 19 which are associated with increased post-ablation AF recurrences.20 , 21 Third, sex-based differences in atrial substrate may be a factor. Female sex has been independently associated with increased atrial fibrosis as defined by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.22 Finally, beyond AF recurrence itself, symptom burden can be a driver of readmission. Given that women tend to be more symptomatic from AF than men,3 , 4 an increased desire to seek medical attention may drive readmissions.

A major paradoxical finding in our study was that despite increased complication rates, readmission rates, and lengths of stay among women, the unadjusted cumulative costs for AF ablation were not higher for women. Notably, women had significantly lower costs at index admission for AF ablation, which may have been driven by decreased utilization of cardiac procedures and testing. Specifically, we identified lower rates of cardioversion, all forms of echocardiographic imaging, and other cardiac diagnostic procedures among women. In this study, reduced use of imaging such as intracardiac echocardiography did not appear to lead to increased complications among women. In an exploratory analysis, we identified no difference in unadjusted rates of complications among women who underwent intracardiac echocardiography at index admission vs. those who did not (8.0% vs. 9.5%; P = 0.125). Regardless, the reasons for the disparity in management are unclear, especially since female patients in our cohort were older and had more co-morbidities. We found that women were more likely to have procedures performed at lower AF ablation volume hospitals and at non-teaching hospitals and hence, cost considerations may have been a factor. Our findings add to a growing body of literature showing decreased utilization of cardiac testing and procedures among women compared to men who are undergoing treatment for the same diagnoses. A study based on the Nationwide Inpatient Sample found significantly lower rates of echocardiography use among females undergoing cardiac admission when compared to males.23 Another study found that women had increased re-hospitalizations for AF after ablation, but paradoxically had less subsequent cardioversions.11 Finally, younger women with ST elevation myocardial infarction have been shown to be less likely to receive revascularization compared to men.24 This, together with increased pre-hospital delays has translated to increased mortality in women with ST elevation myocardial infarction.25 These unexplained sex-based differences and disparities in care raised by our study (Take home figure) and others underscore the importance of detailed investigation into its root causes.

Take home figure.

Summary of study findings and of potential differences and disparities that account for sex-based differences in outcomes after atrial fibrillation ablation. AF, atrial fibrillation; PV, pulmonary veins.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study based on administrative data from the NRD. Therefore, clinical variables such as type and duration of AF, left atrial volume, left ventricular ejection fraction, body mass index, and medication use were lacking. In addition, details from the AF ablation procedures such as PV isolation technique, targeting of non-PV triggers, and creation of linear ablation lesions were not available. Second, although the NRD sample is designed to approximate the national distribution of hospital characteristics, it is derived from a 50% sample of all US hospitals, which may introduce over- or under-representation of certain hospital types. In addition, the NRD only includes information from 22 states in the USA, which may limit its generalizability to the entire national population. Third, miscoded and missing data can occur in large administrative datasets, which can compromise quality of estimates. However, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project quality control measures are routinely performed to confirm data validity and reliability.26 Fourth, patients who underwent AF ablation in one state but were readmitted to another state would not be tracked by the NRD, which would lead to under-estimation of true readmission rates. Finally, the NRD does not provide information on referring or operating physician demographics which precludes any analysis of physician-based factors that might impact outcomes.

Conclusions

In this contemporary, nationally representative cohort of patients undergoing catheter ablation of AF, female sex was independently associated with worse outcomes. After adjustment for age and co-morbidities with both multivariate regression and inverse probability weighting analysis, women had higher rates of complications and 30-day readmissions. Paradoxically, despite increased complications and readmissions, costs associated with AF ablation were not higher among women, which may have reflected sex-based variations in resource utilization. Our findings underscore the importance of recognizing and distinguishing between sex-based differences and disparities that explain worse outcomes among women after AF ablation.

Funding

The Michael Wolk Heart Foundation, the New York Cardiac Center, Inc., the New York Weill Cornell Medical Center Alumni Council, and the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medicine (UL1-TR002384-01) provided funding for this study. The Michael Wolk Heart Foundation, the New York Cardiac Center, Inc., the New York Weill Cornell Medical Center Alumni Council and the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medicine had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: Dr J.W.C. has received consulting fees from Biosense Webster and fellowship grant support from Biosense Webster and Abbott. Dr S.M.M. has received fees from Boston Scientific for serving on a data safety monitoring board. Dr C.F.L. has received consulting fees from Biotronik. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Declaration of Helsinki

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given that the study is based on a de-identified, publically available administrative database, neither locally appointed ethics committee approval nor informed consent is applicable.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jim W Cheung, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

Edward P Cheng, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

, Xian Wu, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Ilhwan Yeo, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Paul J Christos, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Hooman Kamel, Department of Neurology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA.

Steven M Markowitz, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

Christopher F Liu, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

George Thomas, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

James E Ip, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

Bruce B Lerman, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

Luke K Kim, Weill Cornell Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Group (CORG), Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital, 520 East 70th Street, Starr 4, New York, NY 10021, USA.

See page 3044 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz193)

References

- 1. Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, Larson MG, Beiser AS, McManus DD, Newton-Cheh C, Lubitz SA, Magnani JW, Ellinor PT, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piccini JP, Hammill BG, Sinner MF, Jensen PN, Hernandez AF, Heckbert SR, Benjamin EJ, Curtis LH. Incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1993-2007. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piccini JP, Simon DN, Steinberg BA, Thomas L, Allen LA, Fonarow GC, Gersh B, Hylek E, Kowey PR, Reiffel JA, Naccarelli GV, Chan PS, Spertus JA, Peterson ED. Outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation I and patients. Differences in clinical and functional outcomes of atrial fibrillation in women and men: two-year results from the ORBIT-AF registry. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Humphries KH, Kerr CR, Connolly SJ, Klein G, Boone JA, Green M, Sheldon R, Talajic M, Dorian P, Newman D. New-onset atrial fibrillation: sex differences in presentation, treatment, and outcome. Circulation 2001;103:2365–2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, Castella M, Diener H-C, Heidbuchel H, Hendriks J, Hindricks G, Manolis AS, Oldgren J, Popescu BA, Schotten U, Van Putte B, Vardas P, Agewall S, Camm J, Baron Esquivias G, Budts W, Carerj S, Casselman F, Coca A, De Caterina R, Deftereos S, Dobrev D, Ferro JM, Filippatos G, Fitzsimons D, Gorenek B, Guenoun M, Hohnloser SH, Kolh P, Lip GYH, Manolis A, McMurray J, Ponikowski P, Rosenhek R, Ruschitzka F, Savelieva I, Sharma S, Suwalski P, Tamargo JL, Taylor CJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zeppenfeld K. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kummer BR, Bhave PD, Merkler AE, Gialdini G, Okin PM, Kamel H. Demographic differences in catheter ablation after hospital presentation with symptomatic atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4:e002097.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel N, Deshmukh A, Thakkar B, Coffey JO, Agnihotri K, Patel A, Ainani N, Nalluri N, Patel N, Patel N, Patel N, Badheka AO, Kowalski M, Hendel R, Viles-Gonzalez J, Noseworthy PA, Asirvatham S, Lo K, Myerburg RJ, Mitrani RD. Gender, race, and health insurance status in patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1117–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ganesan AN, Shipp NJ, Brooks AG, Kuklik P, Lau DH, Lim HS, Sullivan T, Roberts-Thomson KC, Sanders P. Long-term outcomes of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e004549.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deshmukh A, Patel NJ, Pant S, Shah N, Chothani A, Mehta K, Grover P, Singh V, Vallurupalli S, Savani GT, Badheka A, Tuliani T, Dabhadkar K, Dibu G, Reddy YM, Sewani A, Kowalski M, Mitrani R, Paydak H, Viles-Gonzalez JF. In-hospital complications associated with catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the United States between 2000 and 2010: analysis of 93 801 procedures. Circulation 2013;128:2104–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, Sanchez JE, Shaheen MH, Burkhardt JD, Bassouni M, Cummings J, Wang Y, Lewis WR, Diaz A, Horton RP, Beheiry S, Hongo R, Gallinghouse GJ, Zagrodzky JD, Bailey SM, Al-Ahmad A, Wang P, Schweikert RA, Natale A. Outcomes and complications of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation in females. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaiser DW, Fan J, Schmitt S, Than CT, Ullal AJ, Piccini JP, Heidenreich PA, Turakhia MP. Gender differences in clinical outcomes after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2016;2:703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michowitz Y, Rahkovich M, Oral H, Zado ES, Tilz R, John S, Denis A, Di Biase L, Winkle RA, Mikhaylov EN, Ruskin JN, Yao Y, Josephson ME, Tanner H, Miller JM, Champagne J, Della Bella P, Kumagai K, Defaye P, Luria D, Lebedev DS, Natale A, Jais P, Hindricks G, Kuck KH, Marchlinski FE, Morady F, Belhassen B. Effects of sex on the incidence of cardiac tamponade after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: results from a worldwide survey in 34 943 atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. Cir Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zylla MM, Brachmann J, Lewalter T, Hoffmann E, Kuck KH, Andresen D, Willems S, Eckardt L, Tebbenjohanns J, Spitzer SG, Schumacher B, Hochadel M, Senges J, Katus HA, Thomas D. Sex-related outcome of atrial fibrillation ablation: insights from the German Ablation Registry. Heart Rhythm 2016;13:1837–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, Klein W, Lopez SJ, Montalescot G, White K, Goldberg RJ. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J 2003;24:1815–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Atar D, Badimon L, Bassand JP, De Caterina R, Eikelboom JA, Gulba D, Hamon M, Helft G, Fox KA, Kristensen SD, Rao SV, Verheugt FW, Widimsky P, Zeymer U, Collet JP. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1854–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dagres N, Clague JR, Breithardt G, Borggrefe M. Significant gender-related differences in radiofrequency catheter ablation therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1103–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forleo GB, Tondo C, De Luca L, Dello Russo A, Casella M, De Sanctis V, Clementi F, Fagundes RL, Leo R, Romeo F, Mantica M. Gender-related differences in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2007;9:613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuck KH, Brugada J, Furnkranz A, Chun KRJ, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Schluter M, Elvan A, Braegelmann KM, Kueffer FJ, Arentz T, Albenque JP, Kuhne M, Sticherling C, Tondo C; Fire and Investigators ICE. Impact of female sex on clinical outcomes in the FIRE AND ICE trial of catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018;11:e006204.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee SH, Tai CT, Hsieh MH, Tsao HM, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Huang JL, Lee KT, Chen YJ, Cheng JJ, Chen SA. Predictors of non-pulmonary vein ectopic beats initiating paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: implication for catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayashi K, An Y, Nagashima M, Hiroshima K, Ohe M, Makihara Y, Yamashita K, Yamazato S, Fukunaga M, Sonoda K, Ando K, Goya M. Importance of nonpulmonary vein foci in catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:1918–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hojo R, Fukamizu S, Kitamura T, Aomyama Y, Nishizaki M, Kobayashi Y, Sakurada H, Hiraoka M. Development of nonpulmonary vein foci increases risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after pulmonary vein isolation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017;3:547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Akoum N, Mahnkopf C, Kholmovski EG, Brachmann J, Marrouche NF. Age and sex differences in atrial fibrosis among patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 2018;20:1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papolos A, Narula J, Bavishi C, Chaudhry FA, Sengupta PP. U.S. hospital use of echocardiography: insights from the nationwide inpatient sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khera S, Kolte D, Gupta T, Subramanian KS, Khanna N, Aronow WS, Ahn C, Timmermans RJ, Cooper HA, Fonarow GC, Frishman WH, Panza JA, Bhatt DL. Temporal trends and sex differences in revascularization and outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in younger adults in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1961–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Benamer H, Bataille S, Tafflet M, Jabre P, Dupas F, Laborne FX, Lapostolle F, Lefort H, Juliard JM, Letarnec JY, Lamhaut L, Lebail G, Boche T, Loyeau A, Caussin C, Mapouata M, Karam N, Jouven X, Spaulding C, Lambert Y. Longer pre-hospital delays and higher mortality in women with STEMI: the e-MUST Registry. EuroIntervention 2016;12:e542–e549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barrett ML, Ross DN, HCUP quality control procedures deliverable #1707.05. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/quality.pdf (20 February 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.