Health disparities have been documented across the economic spectrum and around the globe for decades; they are a major societal problem.1 Health disparities among children are particularly important because of their long-term impact on important outcomes, such as adult health, educational attainment, and economic success.2,3 There has been a growing awareness that addressing health disparities extends beyond documenting group-based differences in health outcomes and requires an exploration of the inequalities on which they are founded, often long-standing structural racism and social injustice.2,4 As a result, the idea of progressing toward and achieving “health equity” has gained visibility. There is also increasing recognition that the concept of health equity applies to health policy, health systems, and the professional scope of responsibilities assigned to clinicians, medical educators, researchers, health administrators, public health professionals, and legislators.

We discuss recent conceptualizations of the term “health equity” and present the justification for efforts to advance pediatric health equity. After reviewing the foundational concepts reported in the literature, we conclude with an exploration of the most pressing issues for stakeholders engaged in the pursuit of health equity for children and families.

What Is Health Equity?

There are many definitions for the term “health equity,” and there is considerable overlap in themes. The National Academies’ definition provides a strong foundation: “Health equity is the state in which everyone has the opportunity to attain full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance.”5 Other definitions emphasize the element of justice and the inherent injustice related to experiencing inequalities in opportunities to attain optimal health.6, 7, 8, 9 A consistent theme across all definitions of health equity is the gap between the current and ideal states and enumeration of the factors that impede attainment of the ideal state.10,11 Another common element among definitions is the concept that inequitable health differences are avoidable or preventable.2,6

In the context of clearly defining health equity, it is essential to distinguish the terms “health equity” and “health disparities.” In general, health equity is considered the principle, goal or process that motivates or underpins efforts to eliminate health disparities.12 Alternatively, health disparities have been defined as the yardstick by which we measure progress toward health equity.12 Whereas health disparities focus on individual outcomes or outcomes among specific population subgroups, health equity draws attention to the social, economic, cultural, and environmental conditions that contribute to health outcomes at the population level.8

Achieving the goal of health equity has been recognized as important by many, if not all, members of the health community. The Institute of Medicine's 2001 report, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” catapulted quality into the lexicon of the health professions.13 Equity has been repeatedly defined as an important component or characteristic of quality.14 For instance, each year the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality produces a National Healthcare Disparities report that provides updated information about the type and magnitude of health disparities in an effort to highlight areas of focus for equity efforts.15 In other publications, such as the 2010 Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports, equity has been conceived as a cross-cutting dimension that intersects with all subcomponents of quality.16

In addition, as noted by Beal, the concept of health care disparities was incorporated into the Affordable Care Act of 2010, thereby embedding the concepts of disparities and equity into national policy.17 Professional organizations in the US, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, have also contributed to the national conversation by defining health equity as an essential element for the profession of pediatric, on par with the pillar of the medical home, and many public health departments have established health equity as a priority.18,19 The call for equity has resonated around the world. In 2005, the World Health Organization established the Commission on Social Determinants of Health to review the evidence on global efforts to promote health equity and mobilize the global community.9

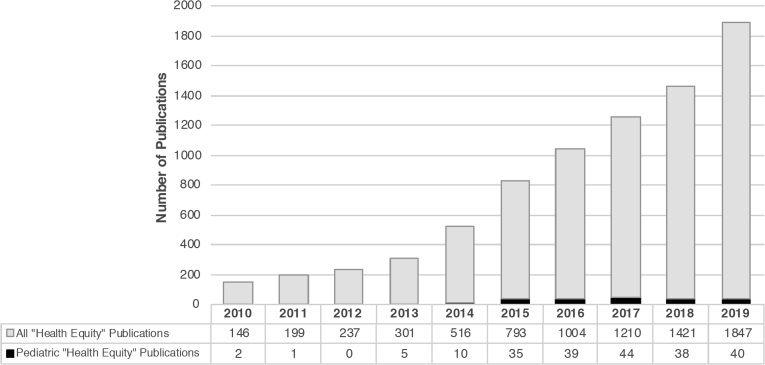

Despite national and international efforts to promote health equity, the scientific literature to date has largely focused on identifying or describing disparities and inequities, with many fewer publications focusing on health equity. In the last decade, however, there has been a sharp increase in publications on health equity. We searched PubMed using the key words “health equity” and documented a tenfold increase in published manuscripts, from 146 in 2010 to 1847 in 2019 (Figure 1). By contrast, the number of publications retrieved using the key words “health disparities” increased 3-fold over the same period (from 612 in 2010 to 2153 in 2019; Figure 2). However, our knowledge of health equity and health disparities in the pediatric population is much more limited. Over 2010-2019, the number of publications retrieved with the key words “health equity” and a term for pediatrics (“pediatric,” “pediatrics,” “child,” or “children”) increased from 2 to 40, and the number of publications identified with the key words “health disparities” and a term for pediatrics increased from 9 to 80 (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

PubMed publications focused on health equity (gray bar) and pediatric health equity (black bar) by year: 2010-2019.

Figure 2.

PubMed publications focused on health disparities (gray bar) and pediatric health disparities (black bar) by year: 2010-2019.

The Arguments for Promoting Health Equity

Many have framed the argument for health equity in ethical terms, highlighting that inequities must be ameliorated because they are, at their root, unfair.9 Indeed, the avoidable and remediable aspects of health inequities are often cited as reasons to explain the fundamental injustice of such inequities.9 For example, Braveman stated “advancing health equity requires societal actions to increase opportunities to be as healthy as possible, particularly for the groups that have suffered avoidable ill health and encountered the greatest social obstacles to achieving optimal health.”4 With regard to children, the American Academy of Pediatrics' Council on Community Pediatrics has noted that the principles of pediatric health equity include a recognition of children's rights, social justice, and ethics.8 In their 2010 policy statement, they emphasized that the well-being of children and their families requires the existence of equity.8

The changing demographics of the US population, however, mandates efforts to address health equity beyond the issue of justice. As highlighted by Beal, the term “minority health status” has traditionally described the health status of racial/ethnic minority groups (non-Whites), but with the growing population of racial/ethnic minorities within the US, the health status of racial/ethnic minorities now actually represents the health status of the general population.17 This is a subtle, but important, demographic transition that also highlights the importance of recognizing, tracking and working to eradicate health inequities that exist by socioeconomic status.17 In addition, health disparities and health inequity have an impact on the national economy, and not solely on the health sector.5 According to the Harvard Business Review, the annual economic impact of racial and ethnic disparities in the US is at least $245 billion as a result of excess health care expenditures, illness-related lost productivity and premature death.20 Thus, whether the justification for efforts addressing health equity is ethical, demographic or financial, there is ample evidence that health equity is linked to broader societal goals of well-being and success for all.

Within academic medicine, the pursuit of health equity extends across mission areas. In the broadest sense, academic health centers have been called to consider their role in improving population health and health-related social justice.21 Academic physicians have recognized that, in addition to conducting research to understand disparities, academia offers an opportunity to amplify the impact of their work by teaching students, residents, and fellows to address health equity.7 This has led to the notion of an “institutional responsibility” toward promoting health equity, a responsibility that is expected to be upheld.7 Beyond research and education, recognizing the need for health equity is critical to the clinical practice of medicine because as Cheng et al pointed out, disparities are fundamentally a “health care quality and safety issue.”22 The argument to prioritize health equity is particularly aligned with pediatrics. Pediatric clinicians are poised to identify disparities and address elements of health equity not only because of the ubiquity of inequities among children but also because of the relatively high number of touchpoints that pediatricians have with their patients in early life.22 As natural champions for the health of children and their families, pediatricians are thus uniquely positioned to understand the drivers of pediatric health inequities and advocate for efforts to address these inequities at the community and population levels.23

Intersectional Concepts that Contribute to Our Understanding of Health Equity

It is impossible to discuss health equity without considering the social determinants of health (SDOH).9 There is widespread acceptance that social factors such as poverty, education, immigration status, access to health care, housing, transportation, food, and employment contribute to health.24 SDOH are estimated to influence up to 80% of all health outcomes and play crucial roles in creating and perpetuating health disparities owing to the way in which broad societal systems and institutional structures lead to inequitable access to protective factors and inequitable burden of harmful ones.25 Thus, efforts to improve health equity at the population level will not be successful unless we take concrete action to address the SDOH.19

Racism is a particularly important social determinant of health. A crucial and growing body of literature has documented the impact of racism as a key driver for the creation and perpetuation of health inequities.21,26 Throughout history, structural and institutional racism have created direct and indirect pathways that contribute to poor access to health care, poor quality of delivered care, increased health risks, and poor health status for marginalized population subgroups.27 This history and the continued reality of racism contribute to mistrust, as individuals who belong to marginalized groups interact with the health system within the broader context of long-standing discrimination, segregation, and inequality.1 This factor is especially true given the manner in which racial bias has permeated both the practice of science and the practice of medicine, resulting systematic mistreatment of minority groups.28, 29, 30 Furthermore, research has documented that health care providers’ biases, both explicit and implicit, are prevalent and have a measurable impact on health care delivery and health outcomes.26,27

The life course framework is another important paradigm that can be used to understand pathways to health and health inequities.31 Previous studies suggest that there may be discrete, critical periods in early life or even during gestation when social exposures, both protective and adverse, can have a lasting impact on health.31 The impact of exposures can accumulate and affect health during an individual's lifetime and may even affect health across generations.8 A growing body of evidence has linked social factors during childhood with chronic diseases of adulthood, such as cardiovascular disease.3 Beyond contributing to our understanding of the development of disease in general, the life course framework could facilitate an understanding of how disparities in early life risk factors predispose, contribute to, or even exacerbate disparities in vulnerabilities or resilience later in life.31 For instance, a life course framework takes into consideration the ways in which early childhood adversity and psychosocial stress, which are disproportionately experienced by certain population subgroups, contribute to the development of disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes or cardiovascular risk in adulthood.31 Emerging research into gene-environment interactions and epigenetic mechanisms have further highlighted the importance of fetal development and early childhood on health across the lifespan and health disparities in the population.21 Thus, it is critical to consider social factors in early life in the development of strategies to combat health inequities, particularly those that may impact multiple generations.

Considerations for Measuring Health Equity

To track the progress toward health equity, we must identify evidence-based indicators and thresholds that define success or progress in health equity. The Healthy People 2020 initiative has led the way by establishing national objectives for health indicators such as childhood immunization rates and tobacco use, encouraging the collection of data on indicator rates across population subgroups to track health disparities, and by defining health equity as one of its overarching goals.32 According to the Healthy People framework, achieving health equity requires the elimination of systematic avoidable differences among subpopulations and the attainment of specific, optimal baseline rates or levels for each health indicator in all subpopulations, although how the optimal rate is determined remains unclear.33

As we search to define indicators of health equity, it is important to note that tracking adherence to clinical care guidelines may not be an appropriate proxy for measuring improvements in health equity for all conditions.32 For example, adult patients who adhere to the recommendations outlined in guidelines for hypercholesterolemia or diabetes have not necessarily experienced fewer disparities in outcomes, in part because the scientific basis for the clinical guidelines has often excluded people with multiple morbidities and from vulnerable communities.32 Given group-level differences in disease processes and the tendency for disadvantaged populations to experience complex interactions between diseases and treatments, solely tracking adherence to clinical guidelines has the potential to obscure opportunities to advance equity and may even reinforce inequities.32

In addition, although it is important to consider how to accurately track progress toward a greater degree of equity for racial/ethnic minorities, it is also crucial to measure and track health inequities among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Although these groups overlap at times, inequities by race/ethnicity vs socioeconomic status may at times require different approaches and thus different metrics for progress.34 Efforts to progress toward health equity must acknowledge that disparities exist across a wide spectrum of privilege.35

Practical Guidelines to Advance the Pursuit of Health Equity

Despite a growing body of literature on health disparities and inequities, there are still needs and gaps that must be addressed to advance the pursuit of health equity. We summarize a series of issues that could be considered practical guidelines for future work by health equity-oriented investigators and other communities of stakeholders.

Strengthen Relationships Between Stakeholders Who Share a Commitment to Health Equity

There is widespread agreement that advancing the agenda of health equity will require collaboration between clinicians, researchers, health system leaders, policymakers, and community stakeholders.36 Given the impact of political, social, and economic forces on the conditions that influence health and contribute to inequities, achieving the goal of health equity will require interdisciplinary and innovative approaches to develop and implement interventions. One sector alone cannot accomplish the breadth and depth of change that is needed.9

Collaborate with Funding Agencies to Prioritize Health Equity

Embracing the goal of achieving health equity will require changes for institutions and agencies that support research and public health interventions. A recent study within the National Institutes of Health documented significant underfunding of both researchers and research related to health disparities and health equity.37 There were significant racial disparities among principal investigators and research topics that received funding: Black scientists were more likely to submit research proposals related to community or population health disparities and interventions and were less likely to be funded than White investigators.37 In this study, the proposed research topic alone accounted for more than 20% of the racial/ethnic disparities in funding, after controlling for variables such as applicant achievement. The authors concluded that proposals which focused on disparities were “less likely to excite the enthusiasm of the scientific community.”37

The challenges of obtaining National Institutes of Health funding for research in health equity contribute to existing funding barriers reported by investigators and equity advocates in other settings. Public health departments, for instance, often rely on sporadic, one-off budget allocations or disease-specific funding opportunities rather than sustained funding.36 The unpredictable nature of funding available through the public sector has damaged the trust between community partners and public health practitioners, 2 groups that are directly affected when interventions or programs are not reliably funded.36 Thus, there is a need for reimagined pathways to provide funding for health equity work, including research projects and other forms of scholarship. Specifically, funding agencies, both private and public, are called to prioritize health equity-oriented projects and to facilitate cross-collaboration and community development through the funding process as a strategy to develop flexible yet sustainable funding streams that can nimbly respond to local needs.36,38

Assess Marginalized Populations’ Unique Needs Related to Health Equity

In general, health disparities research has relied on analyses of existing datasets. Given that many datasets are based on limited sampling among minorities and researchers tend to aggregate raw data into a series of broad categories, the use of existing such datasets has been associated with the masking of inequities and/or the exaggeration of improvements.39 For example, research on birth outcomes among Latina women in the US has consistently demonstrated paradoxically favorable outcomes in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage and barriers to health care.40 However, research on subgroup variation within Latinas has documented significant differences by national origin and birth place and inequities by race or immigration status.41,42 The call for disaggregated data collection applies to Black and Asian communities as well, given the heterogeneity of experience and existence of health disparities that may also exist within racial/ethnic subgroups according to country of origin or other measures.43 Similarly, the use of traditional categories of gender in existing datasets has obscured the health needs of non-cisgender and other sexual minority individuals, which contribute to entrenchment of inequities among LGBTQ communities.39,44

Challenges related to collecting disaggregated data are magnified by the related but distinct issue of ensuring adequate representation of minority groups in research. Racial/ethnic minorities have been historically underrepresented in research, even for conditions or disease processes that disproportionately affect them.45 There are many reasons for this sampling bias, all of which are important to consider, as progress toward health equity is hampered when scientific conclusions are not valid for the populations most at risk of inequities.45

In short, the pursuit of health equity applies to all individuals and communities that experience negative health outcomes and requires collection of data that is designed to capture nuances and variation among subgroups. Traditionally, efforts to ensure detailed data collection has been superseded by the goal of efficiently capturing information from the broadest or largest possible group.46 However, to accurately identify at-risk groups and develop effective interventions and prevention strategies, researchers and non-researchers must develop mechanisms to efficiently collect detailed data, both at the level of investigator-initiated cohort research and within population-level datasets, such as the National Vital Statistics System. Importantly, efforts to create datasets that are inclusive and granular must be accompanied by thoughtful consideration of challenging, sometimes competing, concerns about data governance and privacy.47

Refine the Measurement of SODH

Health systems’ efforts to implement screening for SDOH as a “vital sign” that can be used to identify factors that may culminate in disparities is considered a critical first step in the pursuit toward institutional approaches to achieving health equity.22,48 The emphasis on identifying SDOH has contributed to a proliferation of screening tools, although most tools focus on a single domain.24 Although pediatricians and child health researchers have pioneered research efforts to develop screeners for SDOH, there is a dearth of data regarding the appropriate selection of screening tools, the effectiveness of screeners, and optimal implementation of tools into clinical workflows.25,49 As a result, there is widespread variation in the use of such tools across health care and social service systems.24

In addition, screening for SDOH can have unintended consequences, especially in the absence of appropriate supports and resources, such as patient-centered screening, trauma-informed care, and adequate referral networks and resources.50 Clinicians often have limited knowledge of available resources or solutions for the social needs that are identified, referral pathways, and reimbursement models, all of which are associated with decreased screening rates for SDOH.22 Thus, it is essential to transition from research that is focused solely on describing the SDOH to research that applies SDOH concepts to the development of translatable interventions and health policies. More work is needed to assess the efficacy of SDOH screening tools, potential unintended consequences, and successful implementation models. These efforts will require investigators and health professionals to purposefully consider these issues in their research, programs, and curricula from the time that such efforts are initiated.

Define Pediatric-Specific Health Equity Indicators

To transition from identifying health disparities and their determinants to pursuing health equity, institutions must make health equity a strategic priority.51 To track progress and operationalize this aim, institutional leaders must collect data on health indicators, establish goals, and track progress.51 However, there is currently a lack of data to guide the development of strategic priorities for pediatric health disparities or health equity (Figure 1 and Figure 2). This lack is in part due to the sparse evidence regarding pediatric-specific health indicators.52 For example, the majority of leading health indicators included in Healthy People 2020 report pertain to adolescents or adults.32 Therefore, developing evidence-based pediatric-focused health equity indicators remains an unmet priority.

Prioritize Research on Interventions Aimed at Improving Health Equity

The distinction between health disparities and health equity also highlights the difference between conducting research to document the existence and drivers of disparities and the equally important, although less voluminous, body of work that evaluates interventions aimed at interrupting the drivers of health inequity (Figure 1 and Figure 2). There is an urgent need to move beyond the description of disparities and intentionally focus on developing and implementing interventions that address the drivers of these disparities.21 Although there have been recent efforts to develop interventions and policies aimed at addressing disparities and attaining health equity, our understanding of the health impacts of these efforts remains incomplete.27,53,54 Plainly speaking, we still do not understand how to best address the social needs and inequalities that prevent health equity. Beyond efficacy studies, analyses of the cost, cost effectiveness, and return on investment of interventions that are intended to improve health equity would guide the development of policies and programs on a broader scale.36,53

This dearth of actionable studies may be related to a traditional emphasis on the manifestations of health inequities rather than on the investigation of root causes, including the historical contexts that reify disadvantage.39 Research studies that are oriented toward outcomes instead of prevention have contributed to oversimplified conceptual models, wherein the characteristics of individuals or population subgroups are defined as the problem. Instead, a sharper focus on the structural context and upstream factors that culminate in disproportionate distribution of disease burden is needed.39 In addition, many interventions developed to address health disparities have focused on improving access to health care, but solutions to increase health equity will need to address broader systems of care and determinants of health that operate outside of the healthcare system.38

One example of a health equity-oriented intervention that should be more closely examined is the one-stop shopping model that has been adopted by some health care systems. The model is based on the premise of facilitating access to comprehensive services to address SDOH during primary care or specialty visits.22 This intervention has been used to integrate mental health services, social work, case management, health education, substance use counseling, legal advocacy, career counseling, and other wraparound services within the primary care setting.22,55 Although there has been a significant emphasis on the implementation of such models of care coordination and the rationale for them is sound, there has been limited research to assess the success of their implementation and their efficacy in achieving desired outcomes, particularly in pediatrics.56

More research is needed to better understand how to address the contributions of racism and bias to health inequities.21,26 For instance, there has been widespread use of the implicit bias association test in research studies and academic institutions, particularly among admissions and hiring committees, but there is a lack of data examining whether interventions developed to address implicit bias actually decrease bias in clinical care or other processes. It remains unclear whether these interventions make a difference in patient care and institutional cultures and climates.57 As with the study of other interventions, addressing the role of racism within the health sector will require cross-sectoral collaborations, because the origins and impact of structural racism extend beyond the walls of health care settings.27

Consideration of Appropriate Methodologies for Rigorous Health Equity Research

Strengthening relationships across groups of research stakeholders may require greater prioritization of mixed-method research methodologies.53 Randomized trials, which are considered the pinnacle of scientific evidence, may not be the most appropriate methodology for advancing health equity, because randomized trials often require a controlled scientific environment rather than real-world contexts.53 Other investigators have highlighted the value of complementing controlled studies with contextual qualitative data, such as the lived experiences of those who have been impacted by health inequities.39,58 It is critical to use quantitative and qualitative methods to integrate a diverse set of stakeholders’ input into research design and findings.39,54 From the perspective of pediatric health equity, it is particularly important to consider including the perspectives of families from diverse backgrounds in research protocols and programmatic evaluations.22,59 Similarly, given the role of education as a social determinant of pediatric health, educators are also important stakeholders who should be included in pediatric health equity research.60 Finally, the process of collecting data on the implementation of interventions and outcome indicators of health equity from different voices in distinct sectors will require the development of innovative linkage strategies for existing datasets, as well as the creation of new collaborative data systems.39,61,62

Use Quality Frameworks to Guide Health Equity Research and Interventions

Plans to eliminate disparities and advance equity require tailored approaches that address the root causes of inequities and consider the social, cultural, and political environment in which individuals live and work.14,17 Such contextually tailored approaches are also a foundational aspect of quality improvement efforts. This has prompted recommendations to apply the quality improvement framework to interventions aimed to advance health equity.46 Specifically, the prioritization of patient safety, which began in the 1990s and contributed to the creation of new technologies, infrastructure, and resources to bolster quality improvement efforts, could be leveraged to evaluate strategies intended to advance health equity, especially as we begin to understand that health inequities are patient safety issues.46,51 Many institutions, including the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Academy of Medicine, have recognized the relationship between quality and equity and formally link these concepts or explicitly identify equity as an integral component of quality improvement.14,51,63

Furthermore, applying an equity lens to quality improvement and safety work is considered particularly important to ensure that efforts intended to increase patient safety and health care quality are not unintentionally increasing inequities.46,51,63 This can occur, for instance, when interventions do not account for population-specific drivers or when there are insufficient resources to implement improvement efforts in health care systems or practices that serve minority populations, which leads to differential adoption of evidence-based interventions at the level of health institutions and effectively perpetuate or worsen disparities.3,63 In short, quality improvement and patient safety frameworks may provide useful conceptual approaches and concrete mechanisms to advance and monitor health equity efforts, but more research is needed to assess efficacy and diminish the risk of unintended consequences.46,63

Conclusions: Assessing Success

Recent events related to the public, tragic loss of Black lives have put a spotlight on all social inequities.30 The medical community, including physicians, nurses, and other allied health professionals, is increasingly recognizing the importance of health equity and need for a more equitable society and healthcare system.13,30,51 Many governing bodies and organizations have articulated their commitment to health equity agendas and have reinvigorated these efforts with strategic plans, including pediatric organizations.4,8,13,15,64 There is also global consensus that progressing toward a greater degree of health equity will require a multidimensional approach that includes strengthening individuals and communities, improving the social determinants most closely related to living conditions and the work environment, and promoting the study of interventions and policies aimed at mitigating inequalities.2,9 These statements and acknowledgments are important initial steps; because health inequities have their roots in systemic forms of racism and discrimination that have been codified into policies, we will need innovative and permanent systems-based changes at the societal level.46

Unfortunately, we do not yet have a standard definition of success that will allow us to ascertain that we, as a society, have moved toward a greater degree of health equity. Just as disease is more easily identified and addressed than health, health disparities have been more readily defined and identified than health equity (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Thus, we recommend returning to the outcomes-based definition of health equity: when everyone “has the opportunity to attain full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position.”5

Given the complexity of transitioning from health inequity to health equity, we suggest following indicators of success, stepping stones that signal progress on the path toward achieving health equity. For example, the development of authentic, collaborative relationships between research and non-research-based stakeholders could indicate that the groundwork has been laid for the sustainable implementation of evidence-based equity interventions at the community and population levels.58 Another potential indicator of success could be the allocation of federal research funds to advance health equity, including the prioritization of dissemination and implementation studies and/or interventions that use community-based participatory research. We believe that identifying underlying risk factors and social conditions that contribute to health inequities for marginalized groups will move the needle toward health equity only if our body of knowledge is used as the foundation to develop mitigation and intervention strategies.

As pediatricians, we care for children from all backgrounds and support their journey to adulthood across a discrete, developmentally formative phase of life. Thus, achieving health equity for children can, in turn, promote health equity across the lifespan and across generations.3 Although the goal of health equity remains unrealized in 2020, we are confident that it is attainable through collaboration and partnership between families, community leaders, researchers, clinicians, educators, public health officials, funding agencies, and policymakers.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Footnotes

M-M.P. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32HL098054-11 Training in Critical Care Health Policy Research). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2002. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care; p. 780. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spencer N., Raman S., O’Hare B., Tamburlini G. Addressing inequities in child health and development: towards social justice. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2019;3:e000503. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braveman P., Barclay C. Health disparities beginning in childhood: a life-course perspective. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S163–S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P., Arkin E., Orleans T., Proctor D., Acker J., Plough A. What is health equity? Behav Sci Policy. 2018;4:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States . National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2017. Communities in action: pathways to health equity; p. 582. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P., Arkin E., Orleans T., Proctor D., Plough A. 2017. What Is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? [Internet]. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braveman P.A. Swimming against the tide: challenges in pursuing health equity today. Acad Med. 2019;94:170–171. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Council on Community Pediatrics and Committee on Native American Child Health Policy statement--health equity and children’s rights. Pediatrics. 2010;125:838–849. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Public Health Association Health equity. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.CDC . 2020. Health equity.www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):5–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine (US) National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2014. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century; p. 360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin M.H., Clarke A.R., Nocon R.S., Casey A.A., Goddu A.P., Keesecker N.M., et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.2018 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville (MD): 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services, Committee on Future Directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports . National Academies Press; 2010. Future directions for the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports; p. 246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beal A.C. High-quality health care: the essential route to eliminating disparities and achieving health equity. Health Aff. 2011;30:1868–1871. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AAP AAP agenda for children. www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-facts/AAP-Agenda-for-Children-Strategic-Plan/Pages/AAP-Agenda-for-Children-Strategic-Plan.aspx

- 19.Narain K.D.C., Zimmerman F.J., Richards J., Fielding J.E., Cole B.L., Teutsch S.M., et al. Making strides toward health equity: the experiences of public health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25:342–347. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wheeler S.M., Bryant A.S. Racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck A.F., Edwards E.M., Horbar J.D., Howell E.A., McCormick M.C., Pursley D.M. The color of health: how racism, segregation, and inequality affect the health and well-being of preterm infants and their families. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:227–234. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0513-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng T.L., Emmanuel M.A., Levy D.J., Jenkins R.R. Child health disparities: what can a clinician do? Pediatrics. 2015;136:961–968. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satcher D., Kaczorowski J., Topa D. The expanding role of the pediatrician in improving child health in the 21st century. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4 Suppl):1124–1128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2825C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andermann A. Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Rev. 2018 22;39:19. doi: 10.1186/s40985-018-0094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raphael J.L. Addressing social determinants of health in sickle cell disease: the role of Medicaid policy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28202. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson T.J. Racial bias and its impact on children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67:425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey Z.D., Krieger N., Agénor M., Graves J., Linos N., Bassett M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd R.W., Lindo E.G., Weeks L.D., Lemore M.R. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. 2020. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

- 29.Parsons S. Addressing racial biases in medicine: a review of the literature, critique, and recommendations. Int J Health Serv. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020731420940961. 20731420940961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dreyer B.P., Trent M., Anderson A.T., Askew G.L., Boyd R., Coker T.R., et al. The death of George Floyd: bending the arc of history towards justice for generations of children. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009639. e2020009639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braveman P. What is health equity: and how does a life-course approach take us further toward it? Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:366–372. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CDC . 2020. About healthy people. Healthy People.www.healthypeople.gov/2020/About-Healthy-People [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keppel K., Pamuk E., Lynch J., Carter-Pokras O., Kim I., Mays V., et al. Methodological issues in measuring health disparities. Vital Health Stat 2. 2005;141:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lantz P.M., Rosenbaum S. The potential and realized impact of the Affordable Care Act on health equity. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020 doi: 10.1215/03616878-8543298. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosworth B. Increasing Disparities in Mortality by Socioeconomic Status. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:237–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narain K., Zimmerman F. Advancing health equity: facilitating action on the social determinants of health among public health departments. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:737–738. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoppe T.A., Litovitz A., Willis K.A., Meseroll R.A., Perkins M.J., Hutchins B.I., et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaaw7238. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doykos P., Gray-Akpa K., Mitchell F. New directions for foundations in health equity. Health Aff. 2016;35:1536–1540. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plamondon K.M., Susana Caxaj C., Graham I.D., Bottorff J.L. Connecting knowledge with action for health equity: a critical interpretive synthesis of promising practices. Intl J Equity Health. 2019;18 doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1108-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Hispanic paradox. Lancet. 2015;385:1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60945-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montoya-Williams D., Burris H., Fuentes-Afflick E. Perinatal outcomes in Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states among Hispanic women. JAMA. 2019;322:893–894. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philbin M.M., Flake M., Hatzenbuehler M.L., Hirsch J.S. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen K.H., Trivedi A.N. Asian American access to care in the Affordable Care Act era: findings from a population-based survey in California. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2660–2668. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05328-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacCarthy S., Martino S.C., Burkhart Q., Beckett M.K., Schuster M.A., Quigley D.D., et al. An integrated approach to measuring sexual orientation disparities in women’s access to health services: a national health interview survey application. LGBT Health. 2019;6:87–93. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konkel L. Racial and ethnic disparities in research studies: the challenge of creating more diverse cohorts. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:297–302. doi: 10.1289/ehp.123-A297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sivashanker K., Gandhi T.K. Advancing safety and equity together. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:301–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1911700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Price W.N., 2nd, Cohen I.G. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat Med. 2019;25:37–43. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0272-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arkin E., Braverman P., Egerter S., Williams D. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2014. Time to act: investing in the health of our children and communities. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wortman Z., Tilson E.C., Cohen M.K. Buying health for North Carolinians: addressing nonmedical drivers of health at scale. Health Aff. 2020;39:649–654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garg A., Boynton-Jarrett R., Dworkin P.H. Avoiding the unintended consequences of screening for social determinants of health. JAMA. 2016;316:813–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyatt R., Laderman M., Botwinick L., Mate K., Whittington J. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Cambridge (MA): 2016. Achieving health equity: a guide for health care organizations. IHI white paper. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Starfield B., Gérvas J., Mangin D. Clinical care and health disparities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:89–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farrer L., Marinetti C., Cavaco Y.K., Costongs C. Advocacy for health equity: a synthesis review. Milbank Q. 2015;93:392–437. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penman-Aguilar A., Talih M., Huang D., Moonesinghe R., Bouye K., Beckles G. Measurement of health disparities, health inequities, and social determinants of health to support the advancement of health equity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(Suppl 1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vest J.R., Harris L.E., Haut D.P., Halverson P.K., Menachemi N. Indianapolis provider’s use of wraparound services associated with reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Health Aff. 2018;37:1555–1561. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pannebakker N.M., Fleuren M.A.H., Vlasblom E., Numans M.E., Reijneveld S.A., Kocken P.L. Determinants of adherence to wrap-around care in child and family services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:76. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3774-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maina I.W., Belton T.D., Ginzberg S., Singh A., Johnson T.J. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duran B., Oetzel J., Magarati M., Parker M., Zhou C., Roubideaux Y., et al. Toward health equity: a national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2019;13:337–352. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2019.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schor E.L., American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on the Family Family pediatrics: report of the Task Force on the Family. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1541–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hahn R.A., Truman B.I. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45:657–678. doi: 10.1177/0020731415585986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harrison K.M., Dean H.D. Use of data systems to address social determinants of health: a need to do more. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(Suppl 3):1–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindsell C.J., Stead W.W., Johnson K.B. Action-informed artificial intelligence-matching the algorithm to the problem. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5035. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lion K.C., Raphael J.L. Partnering health disparities research with quality improvement science in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;135:354–361. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Trent M., Dooley D.G., Dougé J., Section on Adolescent Health, Council on Community Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.