Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, critical care, intracranial pressure, mannitol, renal insufficiency, traumatic brain injury

OBJECTIVES:

Mannitol and hypertonic saline are used to treat raised intracerebral pressure in patients with traumatic brain injury, but their possible effects on kidney function and mortality are unknown.

DESIGN:

A post hoc analysis of the erythropoietin trial in traumatic brain injury (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00987454) including daily data on mannitol and hypertonic saline use.

SETTING:

Twenty-nine university-affiliated teaching hospitals in seven countries.

PATIENTS:

A total of 568 patients treated in the ICU for 48 hours without acute kidney injury of whom 43 (7%) received mannitol and 170 (29%) hypertonic saline.

INTERVENTIONS:

None.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

We categorized acute kidney injury stage according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome classification and defined acute kidney injury as any Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome stage-based changes from the admission creatinine. We tested associations between early (first 2 d) mannitol and hypertonic saline and time to acute kidney injury up to ICU discharge and death up to 180 days with Cox regression analysis. Subsequently, acute kidney injury developed more often in patients receiving mannitol (35% vs 10%; p < 0.001) and hypertonic saline (23% vs 10%; p < 0.001). On competing risk analysis including factors associated with acute kidney injury, mannitol (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.3; p = 0.01), but not hypertonic saline (hazard ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.9–2.8; p = 0.08), was independently associated with time to acute kidney injury. In a Cox model for predicting time to death, both the use of mannitol (hazard ratio, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.1; p = 0.03) and hypertonic saline (hazard ratio, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.02–3.2; p = 0.04) were associated with time to death.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, the early use of mannitol, but not hypertonic saline, was independently associated with an increase in acute kidney injury. Our findings suggest the need to further evaluate the use and choice of osmotherapy in traumatic brain injury.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a global health challenge (1–3). Severely injured TBI patients require intensive care and may develop intracranial hypertension (ICHT), which is commonly treated with osmotic agents such as mannitol and hypertonic saline (HTS) (4, 5). Mannitol increases plasma volume and reduces blood viscosity resulting in cerebral vasoconstriction in areas with intact autoregulation. Furthermore, it has an osmotic effect with water removal from cells of areas with an intact blood-brain barrier (6). Finally, mannitol infusion causes a transient increase in serum osmolarity and a shift of intracellular fluid, which decreases intracranial volume (6). Mannitol, however, has side effects including diuresis, electrolyte disturbances, reduction in glomerular filtration ratio (GFR), and may contribute to hypovolemia and renal failure (7, 8). The most recent TBI management guidelines published by the Brain Trauma Foundation recommend using mannitol in patients with intracerebral pressure (ICP) monitoring and ICHT and in patient with clinical suspicion of pending herniation (9). The alternative osmotic agent, HTS, may have certain advantages over mannitol (10). As a plasma expander, HTS increases intravascular volume and blood pressure (5, 11). Although, its routine use in the early phase of TBI care does not appear to improve outcome (12), its effect on the kidney may be less injurious than that of mannitol.

Given the above considerations, we hypothesized that there may be a differential association between renal and clinical outcomes and the administration of mannitol and HTS and that erythropoietin in TBI (EPO-TBI) trial may provide sufficient data to investigate this issue. The EPO-TBI trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00987454) was a randomized controlled multicenter trial comparing the effect of erythropoietin with placebo in intensive care patients with moderate-to-severe TBI. We performed a post hoc analysis of EPO-TBI trial dataset to evaluate associations between the use of osmotic therapy with time to acute kidney injury (AKI) as the primary outcome and time to mortality as secondary outcome.

METHODS

The current study is a post hoc study of the EPO-TBI study a randomized controlled trial conducted in multiple centers between 2010 and 2014 (13). Patients treated in ICU with moderate or severe TBI were screened and included based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria (14). The included patients received either weekly doses of 40,000 international units of subcutaneous epoetin alfa (Eprex Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd, Titusville, NJ) or placebo (0.9% sodium chloride).

Ethical Assessment, Consent, and Trial Registration

Ethical approval was obtained at all EPO-TBI study sites. The patient’s next of kin or legal representative gave informed consent to participation according to local requirements. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00987454), the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12609000827235), and European Drug Regulatory Authorities Clinical Trials (011-005235-22).

Data Collection

The study used a web-based case-record form that included detailed data on patient characteristics, injury mechanism, prehospital care, and immediate hospital management (14). Collected data on illness severity included the International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials (IMPACT) in TBI risk score, the Injury Severity Score (ISS), and the Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score (15). Daily data collected included serum creatinine values, amount and concentration of daily infused mannitol and HTS, whether the patient had an ICP monitor in place, and whether therapeutic hypothermia or hyperventilation was used. In addition, the number of daily hours with an ICP higher than 20 mm Hg was prospectively recorded.

AKI by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Classification and Study Outcomes

Renal function was estimated using daily creatinine levels and categorized according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) (16) classification. We used the first measured creatinine level as the baseline for the assessment of KDIGO during ICU stay. We also estimated preinjury creatinine levels using the modification of diet in renal disease study equation using patient gender and age and an assumed GFR of 75 mL/min for the back calculation (17).

The primary outcome of the study was any AKI, which was defined as the occurrence of any KDIGO stage during ICU care up until 21 days. The exposure of interest was treatment with mannitol or HTS during the first 48 hours. We decided to focus on early mannitol and HTS use, given the unclear evidence regarding late mannitol use in TBI patients (18, 19). We defined no AKI at ICU discharge as the absence of KDIGO stages 1–3 on the day of ICU discharge. We also calculated changes in creatinine after the first 48 hours and compared absolute creatinine levels during days 3–5. The secondary outcome was time to death beyond day 2. Tertiary outcomes included 6-month survival and neurologic function at 6 months with the Glasgow Outcome Scale extended (GOSE). We defined good outcome as a GOSE of 5–8 on a scale of 1–8.

Sample Size

As a post hoc analysis, a priori sample size calculations were not performed. In a previous article, however, we discussed the power of the EPO-TBI trial to identify relevant AKI among the included patients (20). Based on observed frequencies, this study had greater than 80% power (two-sided p = 0.05) to detect hazard ratio (HR) of 2.1 for HTS and 3.7 for mannitol.

Categorical data were compared using chi-square tests with results reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test with results reported as medians (interquartile range). The relationship between mannitol use and time to the development of AKI was determined using multivariable Fine and Gray regression controlling for death (or discharge) as a competing risk with results reported as HRs (95% CI) and presented as cumulate incidence plots with comparison using Gray’s test. Time to death was analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression with results reported as HRs (95% CI) and presented as Kaplan-Meier curves with comparison using log-rank tests. To account for baseline imbalance, each patient’s propensity (probability) of receiving mannitol was determined by logistic regression controlling for imbalanced variables (region, mass lesion evacuation, ICP monitoring, therapeutic hypothermia, hyperventilation during the first 48 hr, and the proportion of time ICP exceeding 20 mm Hg of hours monitored during the first 2 d). All multivariable models were adjusted for site as a random effect, HTS usage in the first 2 days, each patient’s propensity to receive mannitol, and previously described covariates for AKI (20) and mortality (21) (gender, injury mechanism motorcycle or pedestrian accident, TBI severity by IMPACT risk, ISS score, and APACHE II score). To determine effects of overlap between mannitol and HTS, an interaction between mannitol usage and HTS was fitted to the models.

In the model predicting time to AKI, we included patients in the ICU for at least 2 days and excluded AKI occurring during those 2 days. For the mortality model, we excluded patients discharged from the ICU during the first 2 days.

The following multivariable sensitivity analyses were performed:

1) Logistic regression considering AKI and mortality as binomial outcomes.

2) Using estimated preinjury creatinine to determine AKI instead of day 1 values.

3) Using volume of mannitol and HTS.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 24.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Mannitol and HTS Use During the First 2 Days

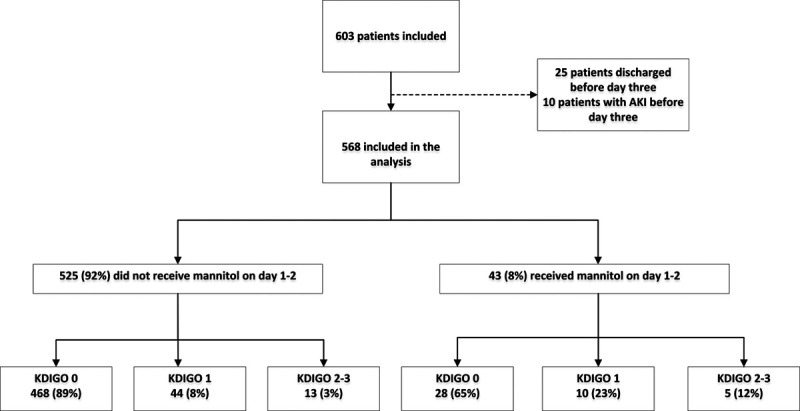

The EPO-TBI trial included a total of 606 patients. Of these, 578 remained in the ICU beyond 2 days with 568 without AKI (Fig. 1). Using admission creatinine as baseline, 82 patients (14%) developed AKI at a median time of 6 days (interquartile range [IQR], 3–8 d) from injury. The corresponding incidence of AKI defined using the estimated creatinine as baseline was 83 patients (14%), with a median time to AKI of 6 days (IQR, 3–9 d). Of the 568 study patients, 183 (32%) received osmotherapy during the first 2 days. Of these, 140 (77%) received only HTS, 13 (7%) received only mannitol, and 30 (16%) received both (Fig. 1) (Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the development of acute kidney injury (AKI) by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) beyond day 3 in patients who did and did not receive early mannitol and remained in the ICU.

The median amount of mannitol administered during the first 2 days was 200 mL (100–325 mL). The most common mannitol concentration was 20% (26/49 [53%]) followed by 25% (21/49 [43%]) and 15% (2/49 [4%]). The median daily amount of mannitol by weight was 0.5 g/kg (IQR, 0.3–0.8 g/kg). The median volume of HTS infused during the first 2 days was 200 mL (IQR, 97.5–933 mL). The most common concentration of HTS used was 3% (49%) followed by 23.4% (27%) and 20% (16%).

Detailed data of patients receiving mannitol and HTS compared with those who did not can be found in Supplemental Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). Supplemental Table 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110) shows the independent predictors of mannitol used to develop the propensity score. There were differences in mannitol use between countries (p < 0.001). Mannitol use was most common in Saudi-Arabia (15%), followed by Europe (7%), Australia (5%), and New Zealand (0%). A similar difference was seen regarding HTS use (p < 0.001). In New Zealand, 41% of patients received HTS, compared with 39% in Saudi-Arabia, 34% in Australia, and 9% in Europe.

Kidney Function in Patients Who Did and Did Not Receive Mannitol or HTS

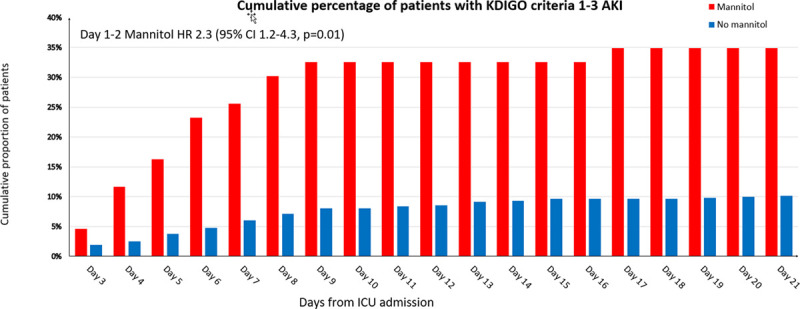

AKI occurred in 15 of 43 mannitol-treated patients (35%) and in 57 of 525 those not treated with mannitol (10%) (p < 0.001). The proportion of patients developing AKI over time based on early mannitol use is shown in Figure 2. Absence of AKI on ICU discharge was more common in those not given mannitol (Table 1). On competing risk regression, early mannitol use was independently associated with time to AKI (HR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.3; p = 0.01) (Table 2) (Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). In contrast, the early use of HTS was not associated with time to AKI (HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.9–2.8; p = 0.08). Sensitivity analysis using a multivariable logistic model predicting any AKI resulted in similar results with early mannitol being associated with AKI (odds ratio, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.3–6.7; p = 0.01) (Supplemental Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). Additional models with AKI assessed with the estimated preinjury creatinine resulted in similar findings with early mannitol predicting time to AKI (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0; p = 0.02) (Supplemental Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110).

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of patients with acute kidney injury (AKI) after day 2 indexed by early use of mannitol. HR = hazard ratio, KDIGO = Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome.

TABLE 1.

Detailed Renal and Clinical Outcomes of Indexed by Osmotherapy Use

| Kidney Function and Outcome | Mannitol (n = 43) | No Mannitol (n = 525) | p | HTS (n = 170) | No HTS (n = 398) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AKI after 2 d, n (%) | 15 (35) | 57 (11) | < 0.001 | 37 (22) | 35 (9) | < 0.001 |

| Absolute change in creatinine between day 3 and 5 (µmol/L), median (interquartile range) | 1 (4.5–11) | –2 (–7 to 3) | 0.003 | –1 (–6 to 5) | –2 (–7 to 2) | 0.005 |

| Proportional change in creatinine between day 3 and day 5 (%), median (interquartile range) | 1 (–5 to 18) | –3 (–10 to 4) | 0.003 | –0.1 (–9 to 9) | –3 (–10 to 3) | 0.003 |

| Median highest creatinine, median (interquartile range) | 73 (63–97) | 72 (62–84) | 0.25 | 72 (64–89) | 72 (62–83) | 0.04 |

| Days to highest Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome stage, median (interquartile range) | 6 (5–9) | 7 (5–10) | 0.53 | 7 (5–9) | 7 (5–11) | 0.96 |

| Renal replacement therapy, n (%) | 1 (2) | 6 (1) | 0.50 | 3 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.45 |

| Lack of AKI at ICU discharge, n (%) | 35 (81) | 509 (97) | < 0.001 | 157 (92) | 387 (97) | < 0.008 |

| ICU LOS, median (interquartile range) | 14 (8–22) | 13 (8–20) | 0.62 | 13 (9–21) | 13 (6–20) | 0.17 |

| Hospital LOS, median (interquartile range) | 27 (9–62) | 26 (15–46) | 0.96 | 28 (14–51) | 25 (15–43) | 0.38 |

| ICU death, n (%) | 12 (28) | 45 (9) | < 0.001 | 30 (18) | 27 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital death, n (%) | 14 (33) | 54 (10) | < 0.001 | 33 (19) | 35 (9) | < 0.001 |

| 6-mo mortality, n (%) | 14 (33) | 62 (12) | < 0.001 | 36 (21) | 40 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Good outcome neurologic outcome (Glasgow Outcome Scale extended 5–8), n (%) | 13 (31) | 289 (56) | 0.002 | 75 (44) | 227 (58) | 0.003 |

AKI = acute kidney injury, HTS = hypertonic saline, LOS = length of stay.

Data regarding creatinine at day 5 were missing in 59 patients on day 5 and in 23 patients on day 3.

TABLE 2.

Competing Risk Regression for the Time to Development of Acute Kidney Injury

| Variables | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.66 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.20 |

| Female | 0.14 (0.03–0.57) | 0.006 | 0.13 (0.03–0.53) | 0.005 |

| Motorcycle or pedestrian accident | 1.97 (1.22–3.16) | 0.005 | 1.81 (1.12–2.92) | 0.02 |

| Injury Severity Score | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.51 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.50 |

| International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials score | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 0.003 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.03 |

| Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II score | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.25 | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 0.80 |

| Any hypertonic saline day 1 or 2a | 2.52 (1.59–4.00) | 0.001 | 1.63 (0.94–2.84) | 0.08 |

| Any mannitol day 1 or 2a | 3.52 (2.00–6.21) | < 0.001 | 2.27 (1.19–4.33) | 0.01 |

| Propensity to receive mannitol | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.0001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.001 |

HR = hazard ratio.

aInteraction between mannitol and hypertonic saline p = 0.81.

In a model including the same covariates but with volumes of osmotherapy, the volume of mannitol (per 100 mL) was associated with time to AKI (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.02–1.3; p = 0.03). No associations was seen with HTS (per 100 mL) regarding time to AKI (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.98–1.06; p = 0.25) (Supplemental Table 5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). All interactions p values for the association between mannitol and HTS use with AKI were nonsignificant.

Patient Survival

Patients who received mannitol or HTS had higher mortality (Table 1). The survival plots of patients who received early mannitol and HTS are shown in Supplemental Figures 4 and 5 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). In a multivariable model including markers of severity of injury and the propensity score for mannitol use, early mannitol (HR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.1; p = 0.03) and HTS (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.02–3.2; p = 0.04) were associated with time to death (Table 3). Similar findings were seen in a logistic regression model predicting death before 180 days (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110). In a model using the same covariates, the volume of mannitol (per 100 mL HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.04–1.45; p = 0.01), but not the volume of HTS (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.93–1.05; p = 0.66), was associated with time to death. (Supplemental Table 7, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/G110).

TABLE 3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Regression for Time to Death

| Variables | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.005 |

| Female | 1.16 (0.65–2.06) | 0.62 | 0.96 (0.52–1.79) | 0.90 |

| Motorcycle or pedestrian accident | 1.12 (0.66–1.89) | 0.68 | 1.20 (0.69–2.08) | 0.52 |

| Injury Severity Score | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.23 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.70 |

| International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials score | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | < 0.0001 | 1.03 (1.01–1.04) | 0.0001 |

| Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II score | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | < 0.0001 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 0.0009 |

| Any hypertonic saline day 1 or 2a | 2.30 (1.47–3.58) | 0.0002 | 1.80 (1.02–3.17) | 0.04 |

| Any mannitol day 1 or 2a | 3.29 (1.84–5.87) | 0.0001 | 2.13 (1.10–4.12) | 0.03 |

| Propensity to receive mannitol | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.0001 | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.006 |

HR = hazard ratio.

aInteraction between mannitol and hypertonic saline p = 0.56.

DISCUSSION

Key Findings

In a post hoc analysis of data collected in a multicenter trial, we found a significant independent association between early mannitol use and AKI with risk appearing associated with the dose of mannitol. We found no such association with HTS. In addition, we demonstrated that both mannitol and HTS were associated with increased mortality, when controlling for injury severity and complexity of TBI care. Our findings highlight the need to further evaluate the role and choice of osmotherapy in TBI.

Relationship to Previous Studies

A recently published study from The Collaborative European Neuro Trauma Effectiveness Research in TBI including 4,500 TBI patients showed that AKI defined according to KDIGO criteria occurred in 10% (22). The development of AKI was associated with both higher mortality and a lower likelihood of good neurologic long-term outcome. Interestingly, as in our study, mannitol but not HTS was significantly associated with development of AKI in patients staying longer than 72 hours. Mannitol-induced AKI may be related to increased serum osmolarity (23). This typically develops 12 hours to 7 days following administration and increases with repeated doses (24). Kim et al (25) observed that 10% of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage administered mannitol developed AKI. Factors associated with risk of AKI were age over 70 years and the pre-existing signs of decreased kidney function such as a GFR less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Lin et al (26) showed that in stroke patients, higher mannitol doses appeared associated with increased AKI risk. Experimental studies demonstrate that HTS can induce vasoconstriction and decreased renal blood flow, mediated by an increase in blood sodium and chloride (27, 28). Although hyperchloremia has been shown to be associated with AKI in critically ill patient, no study has so far shown such a relationship between HTS therapy and AKI (29).

We acknowledge that the most common AKI observed in this study was KDIGO stage 1. Thus, the clinical relevance of this may be challenged. However, stage 1 AKI has been associated with a subsequent greater risk of chronic kidney disease (30). In addition, the EPO-TBI study excluded patients with a high risk of AKI such as the elderly and those with pre-existing severe renal impairment (14). Furthermore, the prevalence of AKI in this sample of TBI patients (10%) was similar to previous studies of AKI after TBI (31) but considerably lower than in patients with major trauma (32). It is plausible that the renal effects of mannitol use in TBI patients with a higher AKI risk, such as patients with diabetes and hypertension, may be considerable.

After adjustment for severity of illness, we found a statistically significant association between early mannitol and HTS use with mortality. It is however plausible that mannitol was used in the more severe cases with pending herniation and those requiring immediate neurosurgery. Nonetheless, concerns regarding mannitol and HTS use in TBI are not new. It has been suggested that repeated mannitol use may result in disruption of the blood-brain barrier and rebound brain edema due to a reverse osmotic gradient (33, 34). In a recent multicenter study by Anstey et al (35) involving around 100 severe TBI patients, a difference in outcome was seen in patients treated only with mannitol compared with those treated only with HTS.

Implications of Study Findings

In this post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial, early mannitol use was less frequent than the use of HTS. Our findings suggest the early use of mannitol, but not HTS, is associated with the development of subsequent AKI. Furthermore, for mortality, the directional effect favors the use of HTS over mannitol. Taken together with previous published observations, our findings support further assessment of mannitol’s safety and efficacy in TBI patients. Until the findings of such full assessments become available, caution should be exercised in its use, especially in patients with additional known risk factors for AKI.

Limitations

We recognize a number of limitations. As this study was not a randomized comparison of mannitol versus HTS, the findings should be seen as hypothesis generating only. It is possible that mannitol was used in patients with a more severe injury, and we may not have controlled for this fully in the analysis. In addition, we had limited data on several variables potentially relevant to the development of AKI: certain patient comorbidities, severity of circulatory shock, arterial blood gases, electrolyte levels, fluid balance, and the use of contrast agents. Finally, because of the sample size and the limited number of patients exposed to mannitol, we were unable to construct more advanced models to assess the exposure to mannitol over time.

CONCLUSIONS

In TBI patients, the early use of mannitol, but not HTS, was independently associated with an increased incidence of AKI. The study design precludes conclusions about causality. However, our findings suggest that HTS may be a safer option than mannitol for the treatment of ICHT in TBI, especially in the presence of additional AKI risk factors. Furthermore, they imply the need to further evaluate the role and choice of osmotherapy in TBI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The current post hoc analysis was planned by Drs. Skrifvars, Bailey, French, Nichol, Cooper, and Bellomo, and all authors were a part of the erythropoietin trial in traumatic brain injury study. Dr. Skrifvars takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and drafted the first version of the article. All authors have read and critically contributed to the final draft.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Erythropoietin trial in traumatic brain injury was supported, in part, by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grant 545902) and the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria (grant D162).

Dr. Skrifvars reports having received a research grant from GE Healthcare, travel reimbursements, and lecture fees from BARD Medical (Ireland), and he received personal research funding from Medicinska Understodsforeningen Liv och Halsa, Finska Läkaresallskapet, Sigrid Juselius Stiftelse, and Svenska Kulturfonden. Dr. Presneill’s institution received funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (project grant ID 545902); he received support from the Victorian Transport Accident Commission (project grant ID D162); and he disclosed off-label product use of erythropoietin trial in traumatic brain injury. Dr. Nichol has received support from the Health Research Board of Ireland. Dr. Little received support for article research from the NHMRC, and she also disclosed off-label product use of Epoetin alfa. Drs. McArthur’s and Cooper’s institutions received funding from the NHMRC. Dr. Cooper’s institution received funding from the Transport Accident Commission and Pressura Neuro. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Myburgh JA, Cooper DJ, Finfer SR, et al. Australasian Traumatic Brain Injury Study (ATBIS) Investigators for the Australian; New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group Epidemiology and 12-month outcomes from traumatic brain injury in Australia and New Zealand. J Trauma. 2008; 64:854–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roozenbeek B, Maas AI, Menon DK. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013; 9:231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raj R, Bendel S, Reinikainen M, et al. Temporal trends in healthcare costs and outcome following ICU admission after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:e302–e309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stocchetti N, Carbonara M, Citerio G, et al. Severe traumatic brain injury: Targeted management in the intensive care unit. Lancet Neurol. 2017; 16:452–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oddo M, Poole D, Helbok R, et al. Fluid therapy in neurointensive care patients: ESICM consensus and clinical practice recommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2018; 44:449–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad SH, Arabi YM. Critical care management of severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012; 20:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manninen PH, Lam AM, Gelb AW, et al. The effect of high-dose mannitol on serum and urine electrolytes and osmolality in neurosurgical patients. Can J Anaesth. 1987; 34:442–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi K, Ogawa N, Suzuki E, et al. Mannitol-induced acute renal failure. Am J Med. 2003; 115:593–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carney N, Totten AM, O’Reilly C, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, fourth edition. Neurosurgery. 2017; 80:6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harutjunyan L, Holz C, Rieger A, et al. Efficiency of 7.2% hypertonic saline hydroxyethyl starch 200/0.5 versus mannitol 15% in the treatment of increased intracranial pressure in neurosurgical patients - a randomized clinical trial [ISRCTN62699180]. Crit Care. 2005; 9:R530–R540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boone MD, Oren-Grinberg A, Robinson TM, et al. Mannitol or hypertonic saline in the setting of traumatic brain injury: What have we learned? Surg Neurol Int. 2015; 6:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper DJ, Myles PS, McDermott FT, et al. HTS Study Investigators Prehospital hypertonic saline resuscitation of patients with hypotension and severe traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 291:1350–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichol A, French C, Little L, et al. EPO-TBI Investigators; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group Erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury (EPO-TBI): A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015; 386:2499–2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nichol A, French C, Little L, et al. EPO-TBI Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group Erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015; 16:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmarou A, Lu J, Butcher I, et al. Prognostic value of the Glasgow Coma Scale and pupil reactivity in traumatic brain injury assessed pre-hospital and on enrollment: An IMPACT analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2007; 24:270–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Section 2: AKI definition. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2012; 2:19–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 145:247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shawkat H, Westwood M-M, Mortimer A. Mannitol: A review of its clinical uses. CEACCP. 2012; 12:82–85 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakai A, McCabe A, Roberts I, et al. Mannitol for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; ; (8):CD001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skrifvars MB, Moore E, Mårtensson J, et al. EPO-TBI Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group Erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury associated acute kidney injury: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019; 63:200–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Presneill J, Little L, Nichol A, et al. EPO-TBI Investigators; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group Statistical analysis plan for the erythropoietin in traumatic brain injury trial: A randomised controlled trial of erythropoietin versus placebo in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Trials. 2014; 15:501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robba C, Banzato E, Rebora P, et al. Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) ICU Participants and Investigators Acute kidney injury in traumatic brain injury patients: Results from the collaborative European neurotrauma effectiveness research in traumatic brain injury study. Crit Care Med. 2021; 49:112–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fink ME. Osmotherapy for intracranial hypertension: Mannitol versus hypertonic saline. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2012; 18:640–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomani AZ, Nabi Z, Rashid H, et al. Osmotic nephrosis with mannitol: Review article. Ren Fail. 2014; 36:1169–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MY, Park JH, Kang NR, et al. Increased risk of acute kidney injury associated with higher infusion rate of mannitol in patients with intracranial hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2014; 120:1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin SY, Tang SC, Tsai LK, et al. Incidence and risk factors for acute kidney injury following mannitol infusion in patients with acute stroke: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015; 94:e2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rein JL, Coca SG. “I don’t get no respect”: The role of chloride in acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019; 316:F587–F605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber JG, Branch RA, Nies AS, et al. Influence of hypertonic saline on canine renal blood flow and renin release. Am J Physiol. 1979; 237:F441–F446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suetrong B, Pisitsak C, Boyd JH, et al. Hyperchloremia and moderate increase in serum chloride are associated with acute kidney injury in severe sepsis and septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2016; 20:315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See EJ, Jayasinghe K, Glassford N, et al. Long-term risk of adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies using consensus definitions of exposure. Kidney Int. 2019; 95:160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore EM, Bellomo R, Nichol A, et al. The incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with traumatic brain injury. Ren Fail. 2010; 32:1060–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Søvik S, Isachsen MS, Nordhuus KM, et al. Acute kidney injury in trauma patients admitted to the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019; 45:407–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castillo LB, Bugedo GA, Paranhos JL. Mannitol or hypertonic saline for intracranial hypertension? A point of view. Crit Care Resusc. 2009; 11:151–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettilä V, Cooper DJ. Treating intracranial hypertension: Time to abandon mannitol? Crit Care Resusc. 2009; 11:94–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anstey JR, Taccone FS, Udy AA, et al. TBI Collaborative Early osmotherapy in severe traumatic brain injury: An international multicenter study. J Neurotrauma. 2020; 37:178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.