Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

The neuronal substrate is highly sensitive to temperature elevation; however, its impact on the fate of the ischemic penumbra has not been established. We analyzed interactions between temperature and penumbral expansion among successfully reperfused patients with acute ischemic stroke, hypothesizing infarction growth and worse outcomes among patients with fever who achieve full reperfusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data from 129 successfully reperfused (modified TICI 2b/3) patients (mean age, 65 ± 15 years) presenting within 12 hours of onset were examined from a prospectively collected acute ischemic stroke registry. CT perfusion was analyzed to produce infarct core, hypoperfusion, and penumbral mismatch volumes. Final DWI infarction volumes were measured, and relative infarction growth was computed. Systemic temperatures were recorded throughout hospitalization. Correlational and logistic regression analyses assessed the associations between fever (>37.5°C) and both relative infarction growth and favorable clinical outcome (90-day mRS of ≤2), corrected for NIHSS score, reperfusion times, and age. An optimized model for outcome prediction was computed by using the Akaike Information Criterion.

RESULTS:

The median presentation NIHSS score was 18 (interquartile range, 14–22). Median (interquartile range) CTP-derived volumes were: core = 9.6 mL (1.5–25.3 mL); hypoperfusion = 133 mL (84.2–204 mL); and final infarct volume = 9.6 mL (8.3–45.2 mL). Highly significant correlations were observed between temperature of >37.5°C and relative infarction growth (Kendall τ correlation coefficient = 0.24, P = .002). Odds ratios for favorable clinical outcome suggested a trend toward significance for fever in predicting a 90-day mRS of ≤2 (OR = 0.31, P = .05). The optimized predictive model for favorable outcomes included age, NIHSS score, procedure time to reperfusion, and fever. Likelihood ratios confirmed the superiority of fever inclusion (P < .05). Baseline temperature, range, and maximum temperature did not meet statistical significance.

CONCLUSIONS:

These findings suggest that imaging and clinical outcomes may be affected by systemic temperature elevations, promoting infarction growth despite reperfusion.

The exquisite temperature sensitivity of the neuronal substrate has been detailed extensively since initial reports in canine models in the early 20th century.1 The development of pyrexia following acute ischemic stroke (AIS) has been well-documented and has been tied to stroke severity, infarct size, and poor functional outcomes, as well as to both short-term and long-term mortality.2–6

The untoward impact of even small brain temperature elevations during ischemic injury is well-described, with histopathologic evidence of irreversible ischemic injury varying substantially with minor temperature changes, and even across physiologic ranges.7 It remains unclear, however, whether temperature elevation is associated with poor outcome as a causal factor driving stroke severity and penumbral expansion or as an epiphenomenon to inherently severe or extensive ischemic injury.

The goals of this study were to analyze the impact of temperature elevation on the fate of at-risk tissues as derived from the penumbra paradigm of cerebrovascular ischemia by using CTP. We studied the interaction of systemic temperature fluctuations with expansion of infarcted tissues in a cohort of successfully reperfused patients with AIS, hypothesizing greater relative infarction growth as a function of temperature elevation in the early aftermath of AIS.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We retrospectively reviewed a prospectively collected endovascular stroke therapy registry of 605 consecutive patients at the Marcus Stroke and Neuroscience Center at Grady Memorial Hospital, spanning December 2010 to September 2014, with approval of the institutional review board. Patients were included for analysis if they met all of the following criteria: 1) AIS due to cerebrovascular large-vessel occlusion, including the internal carotid artery, anterior cerebral artery, and/or the middle cerebral artery (M1 and/or M2 segments), or vertebrobasilar circulation on CTA; 2) time from last known well to groin puncture, ≤12 hours; 3) successful endovascular reperfusion (mTICI 2b/3); and 4) full CTP datasets obtained and technically adequate for analysis of ischemic core and penumbral volumes.

Imaging Protocol

All patients underwent an institutional imaging protocol, including noncontrast CT, CTA, and CTP. CT was performed on a 40-mm, 64–detector row clinical system (LightSpeed VCT; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Helical noncontrast CT (120 kV, 100–350 auto-mA) was performed from the foramen magnum through the vertex at a 5.0-mm section thickness. In the absence of visible intracranial hemorrhage during real-time evaluation by a radiologist and stroke neurologist, 2 contiguous CTP slabs were obtained for 8-cm combined coverage of the supratentorial brain, obtained at eight 5-mm sections per slab. Cine mode acquisition (80 kV, 100 mA) permitting high-temporal-resolution (1-second sampling interval) dynamic bolus passage imaging was obtained following the administration of 35 mL of iodinated contrast (iopamidol, Isovue 370; Bracco, Princeton, New Jersey), power injected at 5 mL/s through an 18-ga or larger antecubital IV access. Contrast administration was followed by a 25-mL saline flush at the same rate. Lastly, helical CTA (120 kV, 200–350 auto-mA) was performed from the carina to the vertex (section thickness/interval, 0.625/0.375 mm) following IV administration of 70 mL of iodinated contrast injected at 5 mL/s and followed by a 25-mL saline flush. All images were transferred to a separate workstation for analysis (Apple Mac Pro; Apple, Cupertino, California) by using a third-party viewer (OsiriX 64-bit; http://www.osirix-viewer.com).

CT Perfusion Analysis

All perfusion imaging was processed by using the fully user- and vendor-independent software platform RApid processing of PerfusIon and Diffusion (RAPID version 4.5; iSchemaView, Stanford, California) to produce irreversible infarction core and total hypoperfused tissue volume estimates, detailed below. Details of the CTP processing pipeline were provided previously.8 Briefly, following preprocessing steps correcting rigid body motion, arterial input function selection was performed and deconvolved from the voxel time-attenuation course using a delay-insensitive algorithm for isolation of the tissue residue function (R). Time-to-maximum (Tmax) of R was determined on a voxelwise basis, with Tmax maps thresholded at 6 seconds and overlaid on the source CTP data. All analyses and data collection were performed under the direct supervision of a dedicated neuroradiologist (S.D.) with subspecialty certification and >8 years of experience in advanced clinical stroke imaging and research, and blinded to the clinical and outcome data.

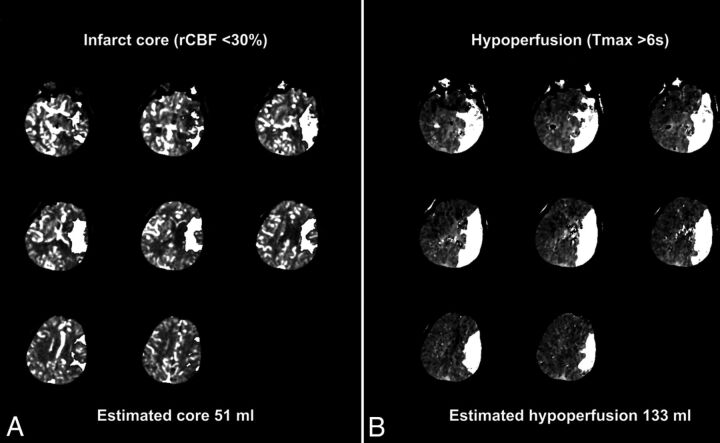

CBF expressed in milliliters/100 g/min was computed on a voxelwise basis for estimation of irreversibly infarcted (core) tissues determined at relative CBF <30% of contralateral normal tissues, as conducted recently in the clinical and stroke trial setting.8,9 Processed maps were automatically generated and overlaid on source images for review purposes. A mismatch volume defining the putative ischemic penumbra was calculated as the difference between Tmax >6 volumes and relative CBF core infarction volumes (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

CT perfusion mismatch maps for infarct core and penumbral volume estimates. Representative sample of the CT perfusion analysis pipeline with estimated infarction core (A) determined as relative cerebral blood flow <30% of normal and total hypoperfused tissue volume (B) measured from regions of time-to-maximum of residue function of >6 seconds. Lesion estimates (white overlays) produced from sequential sections obtained from presentation CT perfusion in a 62-year-old woman presenting with acute left MCA syndrome. Segmented lesions are overlaid on raw perfusion images for review purposes, and automated lesion volumes are produced as shown. Penumbral mismatch is computed from the difference between estimated lesion volumes and is summed for each of 2 contiguous perfusion slabs.

Temperature Analysis

Systemic temperatures were recovered from the patient medical record, beginning from the initial presentation and continuously to the time of follow-up MR imaging, up to every 15 minutes, with minima, maxima, and total ranges collected for each patient. Tympanic temperatures were preferentially used for analysis. In addition to maximum temperature, the following temperature-related parameters were determined for each patient: 1) presentation baseline temperature, 2) temperature range (maximum-minimum), and 3) dichotomized fever (defined as a temperature of >37.5°C during the recording period).10 Patient records were reviewed for positive cultures or other clinical factors indicating the presence of profound systemic infection during hospitalization and up to the time of final follow-up imaging. Antipyretic administration was obtained from the medical record. Data on procedure duration for endovascular thrombectomy and the use of general or monitored anesthesia care were collected from intraoperative reports.

Imaging Outcome

All patients underwent follow-up MR imaging with diffusion-weighted imaging for determination of final infarction volumes before discharge. A semiautomated DWI lesion mask and segmentation methodology were used, with full details of the analysis pipeline elaborated previously.8 Final infarct volumes were used to compute relative infarction growth, defined as [(final infarction volume–initial CTP core)/initial CTP mismatch], and were computed for each patient as a measure of the relative expansion of initial infarction core by incorporation of the initial at-risk volume. Imaging analysis and final infarction volume measures were conducted under the direct supervision of the same neuroradiologist (S.D.), again blinded to other clinical, imaging, and outcome data.

Clinical Outcome

Ninety-day mRS was determined by mRS-certified investigators on clinical follow-up or by phone interview. Favorable clinical outcomes were assigned at a 90-day mRS of ≤2.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD or median and interquartile ranges. The Kendall τ correlation coefficient test (denoted as τ) was applied to assess the nonlinear relationship between temperature-related parameters (baseline temperature, range, maximum, and fever >37.5°C) versus the primary outcome variable of relative infarction growth.

A linear regression model was fitted with relative infarction growth as the response variable and age, presentation NIHSS, last-known-well time to reperfusion, and procedure time to reperfusion as covariates, to establish the correlation of temperature with relative infarction growth, corrected for potentially confounding variables.

The impact of temperature on the likelihood of favorable clinical outcome, mRS ≤ 2, was secondarily tested. The Kendall τ correlation between the same temperature profiles described above and favorable clinical outcome was computed with statistical significance set to P < .05. An additional 2-sample t test was conducted to test the difference in likelihoods of favorable clinical outcome as a function of differences in systemic temperature ranges and fever. Odds ratios for favorable clinical outcome were evaluated in binary logistic regression, with a 90-day mRS of ≤2 as the outcome variable, expressed as OR and 95% confidence intervals. Age, presentation NIHSS score, initial core volume, procedure time, time to reperfusion, temperature change from baseline, range, maximum, and fever (temperature of >37.5°C) were assessed in the development of a multivariable model for prediction of favorable clinical outcome by using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for model selection. Optimal model selection was achieved by minimization of AIC, and the final model was tested by both a goodness-of-fit test and a likelihood ratio to inform the significance of inclusion of temperature in the prediction of favorable clinical outcome. Statistical analysis was performed in R (R statistical and computing software; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

One hundred twenty-nine patients of the 605 consecutive patients with AIS who underwent endovascular therapy during the study period met the inclusion criteria for the current analysis. The main reason for exclusion from the study was the lack of routine CTP preceding thrombectomy early in the study period, before full incorporation of CTP into our stroke imaging protocol, affecting 373 patients. The remainder were excluded due to some combination of unsuccessful reperfusion, thrombectomy outside the 12-hour window, and isolated extracranial occlusions. Demographic details of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, among patients meeting all the inclusion criteria, the median age was 65 years (interquartile range [IQR], 18–94 years). Sixty were women (median age, 68.5 years; IQR, 17–94 years); 69 were men (median age, 64 years; IQR, 30–86 years). The median baseline NIHSS score was 18 (IQR, 14–22). The site of vessel occlusion was distributed as follows: intracranial ICA = 17; extracranial ICA = 2; M1 = 63; M2 = 24; anterior cerebral artery = 4; vertebrobasilar = 1; tandem cervical ICA with intracranial ICA or proximal MCA lesions = 18.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics and temperature profilea

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 65 (range, 18–94) |

| NIHSS score | 18 (14–22) |

| Women | 60 (46.5%) |

| Presentation core infarction volumeb | 9.6 mL (1.5–25.3) |

| Hypoperfused volumec | 132.6 mL (84.2–204) |

| Occluded vessels | n (%) |

| Intracranial ICA | 17 (13.2%) |

| Extracranial ICA | 2 (1.6%) |

| M1 MCA | 63 (48.8%) |

| M2 MCA | 24 (18.6%) |

| ACA | 4 (3.1%) |

| Vertebrobasilar | 1 (0.8%) |

| Tandem | 18 (14%) |

| Reperfusion score | |

| mTICI 2b | 67 (52.9%) |

| mTICI 3 | 62 (48.1%) |

| Last known well to reperfusion | 414 min (295–572) |

| CTP to reperfusion | 119 min (84–162) |

| Procedure time to reperfusion | 58.0 min (38.5–94.5) |

| Total procedural duration | 77 min (51–118) |

| CTP-to-MRI time | 26.8 hr (20–47.2) |

| Last known well to MRI | 30.6 hr (24.0–51.2) |

| General anesthesia (No.) | 44 (34.1%) |

| Aspirin therapy (No.) | 125 (96.9%) |

| Received acetaminophen (No.) | 91 (70.5%) |

| Final infarct volume | 19.6 mL (8.3–45.2 mL) |

| Mean 90-day mRS | 2 |

| Favorable clinical outcome (mRS ≤2) (No.) | 77 (59.7%) |

| 90-day mortality (No.) | 11 (8.5%) |

| Population temperature minima (mean) | 35.3°C |

| Population temperature maxima (mean) | 37.9°C |

| Per-patient temperature fluctuation | 2.4°C (1.8°C–3.3°C) |

| Temperature increase from baseline | 1.6°C (1.0°C–2.5°C) |

Note:—ACA indicates anterior cerebral artery.

Data are reported as proportions and median (IQR), unless otherwise stated.

Relative cerebral blood flow <30% of contralateral normal tissues.

Tmax of >6 seconds.

Median presentation CTP core infarction volume was 9.6 mL (IQR, 1.5–25.3 mL), and the median hypoperfused volume at Tmax > 6 seconds was 132.6 mL (IQR, 84.2–204 mL). Median procedure time to reperfusion was 58.0 minutes (IQR, 38.5–94.5 minutes). Forty-four patients (34.1%) received general anesthesia. The median time from last known well to reperfusion was 414 minutes (IQR, 294.5–572.3 minutes), and median CTP to reperfusion was 119 minutes (IQR, 84–162.5 minutes). A total of 67 (52.9%) patients achieved modified TICI (mTICI) 2b, and 62 (48.1%) achieved mTICI 3 reperfusion. The median time from CTP to follow-up MR imaging was 26.8 hours (IQR, 20.0–47.2 hours). The median final DWI infarct volume was 19.6 mL (IQR, 8.3–45.2 mL). The mean 90-day mRS score was 2, and 77 (59.7%) patients achieved a favorable clinical outcome as characterized by a 90-day mRS of ≤ 2. The 90-day mortality was 8.5% (11 patients).

The mean of the population temperature minima was 35.3°C, and maxima, 37.9°C. A median per-patient temperature fluctuation in the population of 2.4°C (IQR, 1.8°C–3.3°C) was observed. The median temperature increase from presentation baseline was 1.6°C (IQR, 1.0°C–2.5°C). Relative infarction growth corresponding to the first and third quartiles of temperature elevation was 19.0% and 66.6%, respectively. Ninety-one patients (70.5%), reached a maximum temperature of >37.5°C. The median infarction expansion was 8.3 mL (IQR, 22.0 mL). Ninety-five patients (73.6%) had expansion of their infarction; of these, 71 (74.7%) also had fever. All except 4 patients (96.9%) received aspirin therapy; 91 patients (70.5%) received at least 1 dose of acetaminophen during hospitalization. No patients were found to have evidence of severe systemic infections or septicemia prior to their final imaging analysis.

Imaging Outcomes

The Kendall τ correlation between fever and relative infarction growth demonstrated significant associations among patients with a temperature of >37.5°C (τ = 0.27, P < .001). Fever exceeding 37.5°C did not, however, correlate with the size of the initial core (P = .14). Additionally, initial core volume had a small but significant association with relative infarction growth (τ = −0.24, P < .001). When corrected for the potential confounders of age, procedure time, onset to reperfusion, initial NIHSS score, initial CTP predicted core volume, and time from symptom onset, the presence of fever (>37.5°C) remained significantly correlated with infarction expansion (τ = 0.24, P = .002). By comparison, correlations for baseline temperature at presentation (τ = 0.06, P = .38), range (τ = 0.01, P = .89), and maximum (τ = 0.12, P = .053) did not reach statistical significance when adjusted.

Clinical Outcomes

Similar results were observed in a 2-sample t test examining the relationship among fever (P = .002), temperature range (P = .03), and absolute temperature maximum (P = .03) and favorable clinical outcome, while statistical significance was not achieved for baseline temperature or temperature range in relation to favorable clinical outcome.

The results of binary logistic regression with model selection by using AIC produced an optimized model for prediction of favorable clinical outcome, which included variables of age, NIHSS score, procedure time, and fever of >37.5°C, while initial core volume; baseline temperature, range, and maximum; and time from symptom onset to reperfusion did not meet optimization criteria in AIC (Table 2). The likelihood ratio testing confirmed the superiority for model inclusion of fever (P < .05) compared with the elimination of fever from the model, and the goodness-of-fit test further supported the robustness of the selected model for prediction of favorable clinical outcome (P > .05).

Table 2:

Optimal model for prediction of favorable clinical outcome: variable selection by Akaike Information Criteriona

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever (>37.5°C) | 0.31 | 0.09–0.96 | .052 |

| Age | 0.96 | 0.92–0.99 | .007 |

| Total procedure time | 0.99 | 0.98–0.995 | .003 |

| NIHSS score | 0.84 | 0.75–0.92 | <.001 |

Variable selection using Akaike Information Criterion minimization, indicated by the goodness-of-fit test (P > .05), and the likelihood ratio test for inclusion of fever (P = .041) vs exclusion of fever in the prediction of favorable clinical outcome.

Adjusted odds ratios for favorable clinical outcome were computed, suggesting a possible trend toward significance for fever in the likelihood of 90-day mRS of ≤2 (OR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.08–0.97; P = .056). The remaining temperature-related parameters did not approach statistical significance (P > .05).

Discussion

These findings lend further support to the hypothesized, detrimental influence of temperature elevation on the fate of ischemic tissues in the early aftermath of cerebrovascular injury. The sensitivity of the neurovascular unit to potentially subclinical temperature elevations and, conversely, the neuroprotective attributes of therapeutic hypothermia have been observed in humans, as well as in nonhuman experimental animal models.11,12 However, this study represents, to our knowledge, the first investigation of the interaction between systemic temperature change and the fate of reperfused tissues following AIS. In this study, reaching febrile temperatures during hospitalization impacted not only relative infarction growth in a cohort of reperfused patients with AIS but moreover suggested a possible negative influence on the likelihood of favorable clinical outcome. This association remained significant even when correcting for known confounders such as age, procedure time, initial stroke severity (NIHSS score), and CTP predicted core size, as well as all reperfusion and procedural times. Although these variables demonstrated significant associations, in the development of a parsimonious and optimized model, only age, procedure time, and initial NIHSS score met inclusion in the final AIC model, in keeping with findings in recent trials reporting that the association between endovascular therapy and good functional outcomes is not strictly time-dependent among patients presenting within 12 hours.13

Our findings add to earlier work establishing the association between poor long-term outcome and even small increases in systemic temperatures.5,14,15 The influence of systemic temperature changes on the rescue or progression of putatively at-risk brain tissues is likely multifactorial and may be nonlinear; accordingly, within our analysis, the modest but highly significant correlation between elevated temperatures and relative infarction growth may belie the overall complexity of this relationship. Nevertheless, just as therapeutic hypothermia regimens aim for the achievement of a predefined minimum temperature to achieve neuroprotection, the negative influence of temperature elevation in this study was observed at a discrete febrile temperature (>37.5°) defined a priori.16,17 Importantly, admission temperatures were not significantly associated with the measured outcomes, in line with existing studies suggesting that the effects of temperature elevation may more commonly manifest hours after the initial injury.14,15

Pyrexia represents an adaptive response to numerous exogenous or endogenous stimuli, though particular definitions for fever are inconsistent.18 In the context of neurologic diseases, reported fever thresholds vary, including 37.5°C, which we used in a conservative first approximation of the hypothesized interaction in this study.10 While other fever thresholds could be used in such investigations, our selection was intended to reasonably represent conventions within the literature. For this study, we examined the influence of systemic temperatures on the expansion of initial infarction estimates relative to predicted penumbral volumes. Systemic modes of thermometry were used, given their nearly universal availability and known association with NIHSS severity and clinical outcome.5,6,19,20 More recently, dedicated brain temperature estimates have been achieved noninvasively by MR imaging, expanding the potential for direct brain thermometry beyond the costly and invasive approaches to temperature probe implantation.19,21–23 Noninvasive brain thermometry has emphasized the potential for significant differences between brain and body temperatures, decoupling of the brain-systemic temperature gradient during brain injury, and the presence of intracerebral temperature gradients, which may themselves differ between injured and noninjured tissues.19,21,22 While the influence of systemic temperature elevations on ischemic expansion is apparent from this and other studies, the impact of more specific signatures of brain spatial and temporal temperature gradients remains uncertain and requires continued investigation.

We acknowledge a number of study limitations, particularly those inherent in the retrospective nature of the analysis. These results were obtained from a single-institution prospectively collected stroke registry. Analysis included primarily objective, quantitative data such as systemic temperatures and a fully automated, user-independent software environment for CT perfusion analysis as reported recently in the clinical and trial setting for stroke imaging analysis.24–26 The absolute error of CTP may be non-negligible. However, we contend that the use of a validated user-independent platform for analysis is in line with contemporary clinical and trial implementations of CTP, and we would not anticipate that potential errors relating to such inaccuracies would impart specific bias significantly affecting the relationship between infarct expansion and temperature.8,24,26 Systemic temperatures were primarily tympanic, as detailed in the study “Materials and Methods.” Occasional variability in this respect relates to several factors that could not be controlled within the retrospective design, including patient condition, location within the hospital, and nursing-specific variables requiring the use of urinary catheter temperatures in some circumstances. We believe the systematic bias related to temperature acquisition from different sites to be minor because the concordance between temperatures collected from standard locations is high.27

Several potential medications administered during hospitalization may have an impact on systemic temperatures. Principally, antipyretics such as aspirin and acetaminophen and anesthetics administered during the intervention may affect systemic or brain temperature.28,29 In this study, most patients received aspirin and acetaminophen, and all received anesthetics during endovascular therapy. Unfortunately, sample size limitations precluded direct analysis of the relationship between antipyretic exposure, fever, and ischemic expansion. While this may affect the temperature profile of an individual patient, the goals of this study were to establish the relationship between febrile temperatures and relative infarction growth, irrespective of external influences on temperature profile.

In this study, we aimed to isolate the impact of temperature elevation on relative infarction growth and, to this end, selected a cohort of revascularized patients (mTICI 2b/3). We acknowledge that heterogeneity in full reperfusion and infarction evolution may exist across this cohort, given the inclusion of mTICI 2b, as well as variability in time to follow-up MR imaging; however, previous studies have indicated generally high accuracy in the ability of DWI obtained in the early stroke aftermath (<5 days) to predict chronic infarction volumes and clinical outcomes.30,31

Last, we acknowledge that the duration of time spent at or above the threshold temperature for fever could influence both the rate and extent of relative infarction growth. Unfortunately, this retrospective investigation was not powered to assess such interactions. Further study of a potential dose- and time-dependent response of infarction expansion and fever in a larger population of matched patients is thus warranted.

Conclusions

These preliminary findings suggest that temperature dysregulation may potentiate neuronal injury following acute ischemic stroke, compelling further investigation into the mechanistic and temporal relationship in larger cohorts.20,29,32,33 Infarction progression despite reperfusion is well-documented and multifactorial and not yet fully understood.34 We propose that the relative contribution of temperature elevation remains a comparatively under-recognized factor potentially modulating infarction expansion despite reperfusion. Viable penumbra can be found up to 48 hours following stroke onset, during which time temperature dysregulation may drive ischemic expansion.35 These findings suggest that neuronal fate may be affected by mild temperature changes, motivating future work to further elaborate the nature of this relationship and to advance our understanding of temperature as a biomarker in prognostication following ischemic stroke.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- IQR

interquartile range

- mTICI

modified TICI

- R

tissue residue function

- Tmax

time-to-maximum of the tissue residue function

Footnotes

Disclosures: Raul G. Nogueira—UNRELATED: Other: Stryker Neurovascular (Thrombectory Revascularization of large Vessel Occlusions (TREVO) II trial Principal Investigator—modest; Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) or Computerized Tomography Perfusion (CTP) Assessment With Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention (DAWN) Trial Principal Investigator—no compensation), Medtronic (Solitaire With the Intention For Thrombectomy (SWIFT) Trial Steering Committee—modest; Solitaire With the Intention For Thrombectomy as PRIMary Endovascular Treatment Trial Steering Committee—no compensation; Solitaire FR Thrombectomy for Acute Revascularisation (STAR) Trial Angiographic Core Laboratory—significant), Penumbra (3D Separator Trial Executive Committee—no compensation), Editor-in-Chief of Interventional Neurology Journal (no compensation).

The corresponding author had full access to the data in the study and maintains final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Paper previously presented at: Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, November 29 to December 4, 2015; Chicago, Illinois. “Body Temperature Fluctuations Modulate Infarct Expansion, Penumbral Rescue, and Clinical Outcome in AIS Following Successful Endovascular Reperfusion: Impact of Subclinical Temperature Changes on Ischemic Progression.” Paper No. RC305-11.

References

- 1. Wolfe KB. Effect of hypothermia on cerebral damage resulting from cardiac arrest. Am J Cardiol 1960;6:809–12 10.1016/0002-9149(60)90231-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azzimondi G, Bassein L, Nonino F, et al. Fever in acute stroke worsens prognosis: a prospective study. Stroke 1995;26:2040–43 10.1161/01.STR.26.11.2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Castillo J, Davalos A, Marrugat J, et al. Timing for fever-related brain damage in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 1998;29:2455–60 10.1161/01.STR.29.12.2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hajat C, Hajat S, Sharma P. Effects of poststroke pyrexia on stroke outcome: a meta-analysis of studies in patients. Stroke 2000;31:410–14 10.1161/01.STR.31.2.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kammersgaard LP, Jorgensen HS, Rungby JA, et al. Admission body temperature predicts long-term mortality after acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke 2002;33:1759–62 10.1161/01.STR.0000019910.90280.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reith J, Jorgensen HS, Pedersen PM, et al. Body temperature in acute stroke: relation to stroke severity, infarct size, mortality, and outcome. Lancet 1996;347:422–25 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Busto R, Dietrich WD, Globus MY, et al. Small differences in intraischemic brain temperature critically determine the extent of ischemic neuronal injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1987;7:729–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dehkharghani S, Bammer R, Straka M, et al. Performance and predictive value of a user-independent platform for CT perfusion analysis: threshold-derived automated systems outperform examiner-driven approaches in outcome prediction of acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:1419–25 10.3174/ajnr.A4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Straka M, Albers G, Bammer R. Real-time diffusion-perfusion mismatch analysis in acute stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010:1024–37 10.1002/jmri.22338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Axelrod YK, Diringer MN. Temperature management in acute neurologic disorders. Neurol Clin 2008;26:585–603, xi 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dumitrascu OM, Lamb J, Lyden PD. Still cooling after all these years: meta-analysis of pre-clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia for acute ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36:1157–64 10.1177/0271678X16645112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hong JM, Lee JS, Song HJ, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia after recanalization in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2014;45:134–40 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lansberg MG, Cereda CW, Mlynash M, et al. ; Diffusion and Perfusion Imaging Evaluation for Understanding Stroke Evolution 2 (DEFUSE 2) Study Investigators. Response to endovascular reperfusion is not time-dependent in patients with salvageable tissue. Neurology 2015;85:708–14 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boysen G, Christensen H. Stroke severity determines body temperature in acute stroke. Stroke 2001;32:413–17 10.1161/01.STR.32.2.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim Y, Busto R, Dietrich WD, et al. Delayed postischemic hyperthermia in awake rats worsens the histopathological outcome of transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 1996;27:2274–80; discussion 2281 10.1161/01.STR.27.12.2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krieger DW, De Georgia MA, Abou-Chebl A, et al. Cooling for acute ischemic brain damage (COOL AID): an open pilot study of induced hypothermia in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2001;32:1847–54 10.1161/01.STR.32.8.1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. De Georgia MA, Krieger DW, Abou-Chebl A, et al. Cooling for Acute Ischemic Brain Damage (COOL AID): a feasibility trial of endovascular cooling. Neurology 2004;63:312–17 10.1212/01.WNL.0000129840.66938.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aiyagari V, Diringer MN. Fever control and its impact on outcomes: what is the evidence? J Neurol Sci 2007;261:39–46 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karaszewski B, Carpenter TK, Thomas RG, et al. Relationships between brain and body temperature, clinical and imaging outcomes after ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1083–89 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whiteley WN, Thomas RG, Lowe G, et al. Do acute phase markers explain body temperature and brain temperature after ischemic stroke? Neurology 2012;79:152–58 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f04d8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cady EB, D'Souza PC, Penrice J, et al. The estimation of local brain temperature by in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med 1995;33:862–67 10.1002/mrm.1910330620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dehkharghani S, Mao H, Howell L, et al. Proton resonance frequency chemical shift thermometry: experimental design and validation toward high-resolution noninvasive temperature monitoring and in vivo experience in a nonhuman primate model of acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:1128–35 10.3174/ajnr.A4241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marshall I, Karaszewski B, Wardlaw JM, et al. Measurement of regional brain temperature using proton spectroscopic imaging: validation and application to acute ischemic stroke. Magn Reson Imaging 2006;24:699–706 10.1016/j.mri.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lansberg MG, Straka M, Kemp S, et al. ; DEFUSE 2 study investigators. MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:860–67 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70203-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Yan B, et al. ; EXTEND-IA investigators. A multicenter, randomized, controlled study to investigate EXtending the time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits with Intra-Arterial therapy (EXTEND-IA). Int J Stroke 2014;9:126–32 10.1111/ijs.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. ; SWIFT PRIME Investigators. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2285–95 10.1056/NEJMoa1415061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Christensen H, Boysen G. Acceptable agreement between tympanic and rectal temperatures in acute stroke patients. Int J Clin Pract 2002:56:82–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. den Hertog HM, van der Worp HB, van Gemert HM, et al. An early rise in body temperature is related to unfavorable outcome after stroke: data from the PAIS study. J Neurol 2011;258:302–07 10.1007/s00415-010-5756-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhu M, Nehra D, Ackerman JH, et al. On the role of anesthesia on the body/brain temperature differential in rats. J Therm Biol 2004:29:599–603 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ritzl A, Meisel S, Wittsack HJ, et al. Development of brain infarct volume as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): follow-up of diffusion-weighted MRI lesions. J Magn Reson Imaging 2004;20:201–07 10.1002/jmri.20096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim SM, Kwon SU, Kim JS, et al. Early infarct growth predicts long-term clinical outcome in ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci 2014;347:205–09 10.1016/j.jns.2014.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parry-Jones AR, Liimatainen T, Kauppinen RA, et al. Interleukin-1 exacerbates focal cerebral ischemia and reduces ischemic brain temperature in the rat. Magn Reson Med 2008;59:1239–49 10.1002/mrm.21531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Karaszewski B, Wardlaw JM, Marshall I, et al. Early brain temperature elevation and anaerobic metabolism in human acute ischaemic stroke. Brain 2009;132:955–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haussen DC, Nogueira RG, Elhammady MS, et al. Infarct growth despite full reperfusion in endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg 2016;8:117–21 10.1136/neurintsurg-2014-011497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schlaug G, Benfield A, Baird AE, et al. The ischemic penumbra operationally defined. Neurology 1999;53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]