Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

There are, to date, no MR imaging diagnostic markers for Lewy body dementia. Nigrosome 1, containing dopaminergic cells, in the substantia nigra pars compacta is hyperintense on SWI and has been called the swallow tail sign, disappearing with Parkinson disease. We aimed to study the swallow tail sign and its clinical applicability in Lewy body dementia and hypothesized that the sign would be likewise applicable in Lewy body dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This was a retrospective cross-sectional multicenter study including 97 patients (mean age, 65 ± 10 years; 46% women), consisting of the following: controls (n = 21) and those with Lewy body dementia (n = 19), Alzheimer disease (n = 20), frontotemporal lobe dementia (n = 20), and mild cognitive impairment (n = 17). All patients underwent brain MR imaging, with susceptibility-weighted imaging at 1.5T (n = 46) and 3T (n = 51). The swallow tail sign was assessed independently by 2 neuroradiologists.

RESULTS:

Interrater agreement was moderate (κ = 0.4) between raters. An abnormal swallow tail sign was most common in Lewy body dementia (63%; 95% CI, 41%–85%; P < .001) and had a predictive value only in Lewy body dementia with an odds ratio of 9 (95% CI, 3–28; P < .001). The consensus rating for Lewy body dementia showed a sensitivity of 63%, a specificity of 79%, a negative predictive value of 89%, and an accuracy of 76%; values were higher on 3T compared with 1.5T. The usefulness of the swallow tail sign was rater-dependent with the highest sensitivity equaling 100%.

CONCLUSIONS:

The swallow tail sign has diagnostic potential in Lewy body dementia and may be a complement in the diagnostic work-up of this condition.

Lewy body dementia (LBD) is often regarded as the second most common dementia in older individuals after Alzheimer disease,1,2 possibly sharing the second place with vascular dementia.3 Clinical symptoms of LBD are similar to those of Parkinson disease (PD) dementia and include fluctuating cognitive decline, recurrent visual hallucinations, and parkinsonism.2,4 LBD and PD dementia are separated by the arbitrary 1-year rule: If dementia exists within 12 months of parkinsonism, the patient is classified as having LBD.2,4 More than 12 months of parkinsonism before the onset of dementia is termed “PD dementia.”2,4

Differential diagnostics between LBD and Alzheimer disease (AD) can be difficult, with both clinical and pathologic overlap.2,5,6 LBD distinguishes itself from AD on MR imaging by having a lesser degree of generalized atrophy and commonly sparing or having less severe atrophy of the medial temporal lobes.6 Besides the loss of atrophy, which in itself is nonspecific, no accurate MR imaging signs for the distinction of LBD and other neurodegenerative diagnoses exist. Functional imaging is useful in diagnostic differentiation and typically shows reduced perfusion and glucose metabolism in an AD-like pattern, sparing the medial temporal lobes, with additional involvement of the occipital regions.6–9 Dopaminergic transporter imaging with SPECT is another reliable method of differentiation, with less binding in the striatum suggesting LBD.6

In recent years, MR imaging of the substantia nigra has shown great promise as a diagnostic tool in Parkinson disease.10–14 Pathophysiologically, PD is characterized by loss of pigmented dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta; 60%–80% of neurons are lost even before manifestation of motor symptoms.15 Clusters of dopamine-containing neurons in calbindin-poor zones in the substantia nigra are termed nigrosomes.16 Nigrosome 1, located in the caudal and posterolateral part of the substantia nigra pars compacta, is the largest dopamine-containing cluster and is mostly affected by PD.17 Recently, nigrosome 1 has been described as hyperintense on iron-sensitive SWI sequences,14 resembling a swallow tail.11 The presence of a swallow tail sign has been shown to be sensitive and specific and has a high negative predictive value in PD on 3T MR imaging,11 but its clinical applicability in LBD warrants further investigation.

Due to the similarity in pathophysiology of PD and LBD, the swallow tail sign should be of diagnostic value even in LBD.18 We aimed to determine the clinical applicability of the swallow tail sign in a memory clinic population with a focus on LBD.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study received institutional review board approval. Informed consent was obtained from each patient or a legal guardian in case of severe dementia, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This was a retrospective multicenter cross-sectional study with patient recruitment from memory clinics at the Karolinska, Uppsala, and Lund University Hospitals. All patients were recruited at initial work-up of their disease, and the MR imaging brain scan was obtained concomitantly as part of the memory investigation. Inclusion criteria were the presence of SWI sequences, a diagnosis of subjective cognitive impairment (used as controls), LBD, frontotemporal lobe dementia (FTD), AD, or mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The exclusion criterion was insufficient scan quality. We aimed to have around 20 patients per diagnostic group and recruited the total amount of consecutive patients with SWI from each center (n = 100). Three patients were excluded because of insufficient scan quality due to motion artifacts. In total, we included 97 patients: subjective cognitive impairment (controls) (n = 21), LBD (n = 19), FTD (n = 20), AD (n = 20), and MCI (n = 17).

Patient demographics are detailed in Table 1. Patients with LBD were recruited from all 3 sites; those with FTD, from Uppsala University Hospital; and the remaining patients, from the Karolinska University Hospital.19 All patients had their diagnosis set according to the International Classification of Diseases-10, the clinically used classification criteria in our country. Diagnosis was determined in multidisciplinary rounds, with consideration of all data (clinical, lab, imaging, and neuropsychological) after a thorough memory clinic investigation. CSF analysis was performed as previously described20 on a subgroup of 56 patients and is seen in Table 1.

Table 1:

Mean age and sex distribution across diagnosesa

| Whole Cohort (n = 97) | Controls (n = 21) | LBD (n = 19) | FTD (n = 20) | AD (n = 20) | MCI (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yr) | 65 ± 10 | 60 ± 6 | 72 ± 6 | 64 ± 11 | 72 ± 6 | 62 ± 12 |

| Female (No.) (mean age) (yr) | 45, 46%; 64 ± 11 | 10, 48%; 58 ± 5 | 5, 26%; 74 ± 65 | 10, 50%; 63 ± 13 | 12, 60%; 68 ± 8 | 8, 47%; 60 ± 12 |

| Male (No.) (mean age) (yr) | 52, 54%; 67 ± 10 | 11, 52%; 62 ± 6 | 14, 74%; 72 ± 6 | 10, 50%; 66 ± 9 | 8, 40%; 70 ± 13 | 9, 53%; 64 ± 11 |

| MMSE (mean) | 26 ± 4 | 30 ± 0 | 22 ± 3 | 27 ± 2 | 23 ± 4 | 28 ± 2 |

| Hypertension (No.) (%) | 8 (9) | 3 (14) | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 2 (12) |

| Diabetes (No.) (%) | 2 (2) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Hyperlipidemia (No.) (%) | 6 (7) | 2 (10) | 0 | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 1 (6) |

| CSF amyloid (median) (IQR) (ng/L) | 575 (403–1250) | 1160 (697–1370) | – | 565 (528–565) | 391 (342–524) | 737 (448–1138) |

| CSF T-τ (median) (IQR) (ng/L) | 52 (36–73) | 274 (211–364) | – | 214 (129–214) | 502 (398–873) | 198 (129–417) |

| CSF P-τ (median) (IQR) (ng/L) | 307 (192–458) | 55 (36–75) | – | 36 (22–36) | 84 (61–115) | 37 (28–67) |

| CSF/serum albumin ratio (median) (IQR) | 249 (153–322) | 230 (166–345) | – | 322 (153–322) | 307 (206–730) | 155 (106–376) |

Note:—P-τ indicates phosphorylated τ; T-τ, total τ; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

All patients, except 8 with LBD, had data on hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. CSF data were available for a subgroup of 56 patients (controls = 18; LBD = 0; FTD = 8; AD = 16; MCI = 14).

MR Imaging and Image Assessment

All patients were scanned with full MR imaging protocols, including an SWI sequence (VenBOLD; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) on 1.5 and 3T scanners; parameters and distribution across scanners are included in Table 2. Patients were assigned to the different scanners on the basis of clinical availability; the proportions of patients scanned at 3T were the following: LBD, n = 15, 74%; AD, n = 7, 35%; MCI, n = 10, 59%; FTD, n = 13, 65%; and controls, n = 9, 43%.

Table 2:

Overview of MRI scanners, SWI sequence parameters, and diagnostic distribution

| Karolinska University Hospital |

Lund University Hospital |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avantoa | Tim Trioa | Achievab | Skyraa | |

| Field strength | 1.5T | 3T | 3T | 3T |

| TE (ms) | 40 | 20 | 25 | 20 |

| TR (ms) | 49 | 28 | 17 | 27 |

| Flip angle | 15° | 15° | 15° | 15° |

| Section thickness (mm) | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Patients (No.) (%) | 43 (43) | 37 (40) | 9 (9) | 8 (8) |

| Controls (n = 21) (No.) (%) | 12 (57) | 9 (43) | – | – |

| LBD (n = 19) (No.) (%) | 4 (21) | 5 (26) | 2 (11) | 8 (42) |

| FTD (n = 20) (No.) (%) | 7 (35) | 6 (30) | 7 (35) | – |

| AD (n = 20) (No.) (%) | 13 (65) | 7 (35) | – | – |

| MCI (n = 17) (No.) (%) | 7 (41) | 10 (59) | – | – |

Siemens, Erlangen, Germany.

Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands.

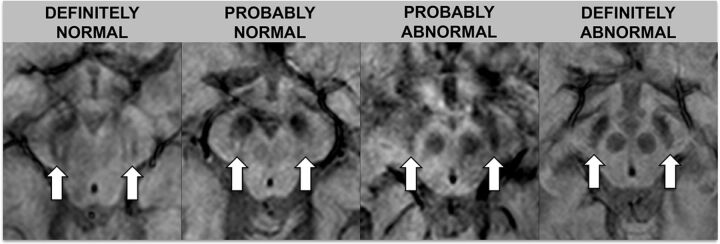

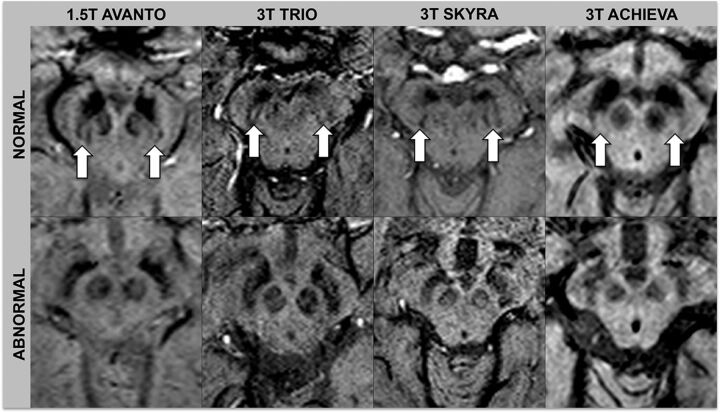

Images were assessed by 2 neuroradiologists (S.H. with 16 years of experience, and S. Schwarz with 9 years of experience). Ratings were performed independently and blinded to diagnosis and the other raters' assessments. One month after independent ratings, a consensus rating, blinded to diagnosis, was performed between the 2 initial raters in conjunction with a third neuroradiologist (E.-M.L with 30 years of experience). The swallow tail sign was rated on an ordinal scale with 5 increments: 0 = unsure, 1 = definitely normal, 2 = probably normal, 3 = probably abnormal, 4 = definitely abnormal. For statistical analysis, the results were dichotomized into normal (ratings 1 and 2) and abnormal (ratings 3 and 4). Raters looked at the nigrosome 1 appearance, located in the posterior third part of the substantia nigra, resembling a swallow tail (Figs 1 and 2).11 Cases with unilateral abnormal findings were considered abnormal. Figures 1 and 2 depict the swallow tail sign.

Fig 1.

Rating scale for the swallow tail sign. The rating scale for the swallow tail sign is detailed in this figure; arrows indicate the normal/abnormal swallow tail signs on SWI sequences.

Fig 2.

Normal and abnormal swallow tail signs across scanners. Arrows indicate the normal swallow tail signs on SWI sequences.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are presented as numbers and percentages. Rating increments for the swallow tail sign were dichotomized into normal (ratings 1 and 2) and abnormal (ratings 3 and 4). Sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values, and accuracy were calculated. χ2 and Fischer exact tests were used for categoric data. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to see whether ratings could predict diagnosis. Diagnosis was set as the dependent variable with the controls as a reference. Rating was dichotomized into normal and abnormal and used as an independent variable. The regression model was controlled for field strength and section thickness (by adding them as covariates in our model). SPSS, Version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis, and P < .05 was set as the threshold of significance, equaling a corrected level of 0.033 after adjustment for the false discovery rate according to the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.21

Results

The κ between raters was 0.4, equaling a moderate agreement, on all scans, as well as on only 1.5T and 3T scans. Table 3 shows the distribution of ratings across raters and diagnoses. The distribution of normal and abnormal swallow tail signs varied significantly across diagnoses (P < .001) (Table 3), and nonsignificantly across different MR imaging scanners (P = .138) for both raters. An abnormal swallow tail sign was significantly more common in LBD than in all other diagnoses (P < .001). The swallow tail sign was abnormal on 1.5 and 3T on consensus rating in the following: controls, 10% (95% CI 0%–23%); LBD, 63% (95% CI, 41%–85%); FTD, 35% (95% CI, 14%–56%); AD, 25% (95% CI, 6%–44%); and MCI, 6% (95% CI, 0%–12%) (Table 3). For rater 1, two patients (2%) had only one of their nigrosomes rated as abnormal, resulting in an abnormal case; the rest of the nigrosomes were bilaterally the same. For rater 2, the corresponding number was 3 (3%) patients. The cases mentioned were not the same for the raters.

Table 3:

Distribution of the abnormal swallow tail sign across diagnosesa

| Controls (n = 21) | LBD (n = 19) | FTD (n = 20) | AD (n = 20) | MCI (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal, 1.5T and 3T (No.) (%) | |||||

| Rater 1 | 2 (10) | 9 (47) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 2 (12) |

| Rater 2 | 5 (24) | 18 (95) | 8 (40) | 9 (45) | 4 (24) |

| Consensus | 2 (10) | 12 (63) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 1 (6) |

| 1.5T | n = 12 | n = 4 | n = 7 | n = 13 | n = 7 |

| Abnormal, 1.5T (No. (%) | |||||

| Rater 1 | 2 (17) | 1 (25) | 3 (43) | 3 (23) | 2 (29) |

| Rater 2 | 4 (33) | 4 (100) | 1 (14) | 6 (46) | 1 (14) |

| Consensus | 2 (17) | 3 (75) | 4 (57) | 3 (23) | 1 (14) |

| 3T | n = 9 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 7 | n = 10 |

| Rater 1 | 0 (0) | 8 (53) | 4 (31) | 2 (29) | 0 (0) |

| Rater 2 | 1 (11) | 14 (93) | 7 (54) | 3 (43) | 3 (30) |

| Consensus | 0 (0) | 9 (60) | 3 (23) | 2 (29) | 0 (0) |

Rater 1, S.H.; rater 2, S.S. Missing cases represent unsure raters due to low-quality images.

Table 4 shows sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracies across raters and field strengths for LBD. The highest sensitivity and negative predictive value were descriptively obtained by rater 2 on 3T (Table 4). Similar values for AD, MCI, and FTD are seen in the On-line Table, showing that the swallow tail sign is only applicable in LBD. In binary logistic regression analysis, controlled for field strength and section thickness, the odds of having LBD with an abnormal swallow tail sign were significant; the swallow tail sign had no predictive value (ie, it was insignificant, in the other diagnoses; Table 5).

Table 4:

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy for Lewy body dementia with the abnormal swallow tail sign

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 and 3T | |||||

| Rater 1 | 50 | 79 | 36 | 87 | 74 |

| Rater 2 | 95 | 66 | 41 | 98 | 72 |

| Consensus | 63 | 79 | 44 | 89 | 76 |

| Consensus, 1.5- and 1.6-mm ST | 69 | 91 | 75 | 88 | 84 |

| Consensus, 2-mm ST | 50 | 69 | 20 | 90 | 67 |

| 1.5T | |||||

| Rater 1, 1.5T | 25 | 75 | 9 | 91 | 70 |

| Rater 2, 1.5T | 80 | 70 | 25 | 97 | 71 |

| Consensus, 1.5T | 60 | 72 | 23 | 93 | 71 |

| 3T | |||||

| Rater 1, 3T | 57 | 84 | 57 | 84 | 76 |

| Rater 2, 3T | 100 | 61 | 50 | 100 | 72 |

| Consensus, 3T | 64 | 86 | 64 | 86 | 80 |

Note:—PPV indicates positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; ST, section thickness.

Table 5:

Predictive role of an abnormal swallow tail sign in cognitive impairmenta

| LBD, OR (95% CI) | FTD, OR (95% CI) | AD, OR (95% CI) | MCI, OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rater 1 | 4 (1–14), P = .010 | 6 (1–39), P = .060 | 3 (1–17), P = .248 | 2 (0–14), P = .668 |

| Rater 2 | 31 (4–244), P = .001 | 11 (0–276), P = .236 | 4 (1–20), P = .070 | 1 (0–4), P = .831 |

| Consensus | 9 (3–28), P <.001 | 7 (1–50), P = .060 | 3 (1–19), P = .229 | 1 (0–10), P = .746 |

Note:—OR indicates odds ratio.

The regression model is controlled for field strength and section thickness.

When comparing the number of abnormal swallow tail signs on 1.5- and 1.6-mm section thicknesses versus 2.0-mm, abnormal swallow tail signs were more frequently seen on 1.5- and 1.6-mm section thicknesses (P = .03). Similarly, descriptively, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, and accuracy were higher with 1.5- and 1.6-mm section thicknesses (Table 4).

Discussion

Considering that no other MR imaging markers for LBD exist, the swallow tail sign may be a useful complement in the diagnosis of LBD. A normal swallow tail sign has a high negative predictive value for exclusion of an LBD diagnosis. However, because 37% of patients with LBD had a normal swallow tail sign, the sign does not qualify as the sole diagnostic test. Accuracy and sensitivity increase with optimized imaging techniques.

To date, the swallow tail sign has mainly been studied in PD. An abnormal swallow tail sign has been shown to be a useful marker in PD with a 100% sensitivity and negative predictive value, 95% specificity, and 69% positive predictive value.11 The swallow tail sign has not been shown to discriminate typical and atypical PD.22 In LBD, the sensitivity and negative predictive value on 3T SWI has been shown to be 93%, with a 87% specificity and positive predictive value.23 No studies exist examining the swallow tail sign in PD dementia. The lower positive predictive value and specificity, as reflected in our study, shows that the swallow tail sign may be abnormal even in other diseases and healthy individuals. However, values may be improved with optimized imaging sequences and techniques.

All our patients were included and had an MR imaging brain scan during their diagnostic work-up. The patients with LBD could thus be considered in their early stages of disease. Thus, this may explain the number of patients rated with a normal swallow tail sign. A similar study with patients in later stages of disease would have been of interest, to see whether results differ. Furthermore, abnormal swallow tail signs were seen in a range of diagnoses, such as in AD and FTD. No study has assessed the distribution and associations of an abnormal swallow tail sign in a large-scale or prospectively acquired memory clinic cohort, to our knowledge. The reason for an abnormal swallow tail sign is not fully known and may be multifactorial. It may represent dopaminergic neuronal loss, neuromelanin loss, or a change in iron storage and oxidation.11,14,24 As the hyperintense feature of the nigrosome 1 decreases, the surrounding hypointensity may increase; this change reduces the demarcation of the nigrosome 1. It would be interesting to see whether dementia-related gait changes, especially because they are more common in dementia than healthy aging,25 are associated with an abnormal swallow tail sign. An abnormal swallow tail sign across dementia diagnoses may also suggest a large overlap in the pathophysiology of cognitive impairment.

Our results demonstrate interindividual variation in the assessment of the swallow tail sign. Despite the use of experienced neuroradiologists, our interrater agreement was moderate, and our interrater variability equals that of another study of swallow tail assessment in PD.22 Consensus ratings resulted in values between both initial ratings. Rater 2 more readily called the swallow tail sign abnormal and, consequently, had a higher sensitivity, at the price of a lower specificity, for LBD. Meanwhile consensus ratings were closer to those of rater 1, showing that rating of the swallow tail sign in a clinical setting is difficult. While the rating was clear and distinct between normal and abnormal in most cases, a substantial portion of patients had less clear findings. This outcome allows individual interpretation of when to call the swallow tail sign abnormal and reflects the challenge of assessing the swallow tail sign and using it as a diagnostic test. Adding to the difficulty of rating and probably lowering our agreement is the inclusion of different MR imaging scanners, field strengths, and section thicknesses in our study. However, this also contributes to our study being more clinically generalizable. Rating of the swallow tail sign, the only MR imaging marker with potential diagnostic value in LBD, should therefore be improved, to increase clinical utility and reliability. We suggest optimizing MR imaging parameters of SWI, including high spatial resolution and high contrast, which should be standardized across MR imaging scanners. Interrater agreement and rating reliability may further be increased with established rating scales,11 such as the one in Fig 1.

Field strength is of importance for the clinical applicability of the swallow tail sign. Accuracy has been shown to be higher at 7T, decreasing with 3T.26 In our cohort, we included both 1.5 and 3T scans, and sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and accuracy for LBD were higher on 3T. Nevertheless, even at 1.5T, the assessment of the swallow tail provided significant information for the diagnosis of LBD. In the absence of other established imaging findings, we argue that though ideally performed at 3T, assessment of the swallow tail sign at 1.5T may still provide added clinical value. Similarly, a thinner section thickness resulted in higher sensitivity for LBD and should be implemented for clinical imaging.

Limitations in our study include the use of multiple scanners and 1.5 and 3T field strengths. However, we performed our statistical analysis subdivided for the different field strengths, and the use of multiple scanners may better reflect the clinical reality. Besides, section thickness and field strength were both corrected for in our regression model. Including the pretest probability of the diagnoses included in our study would have added further insight into the diagnostic use of the swallow tail sign. It would also have increased the external validity of our study, because positive and negative predictive values are influenced by the prevalence of diseases in the population. Subjective cognitive impairment was used as a control group, and to date, clinical methods of detecting whether these individuals may have prodromal disease are scarce. “Subjective cognitive impairment” means patients with no observable clinical or pathologic findings, but with subjective feelings of cognitive decline. Thus, no disease was detected, but using healthy elderly as controls would have provided a cleaner control group. Strengths include a large and well-classified cohort and the use of experienced raters.

Conclusions

The swallow tail sign may be a complement in the diagnosis of LBD but does not qualify as a sole diagnostic marker.

Supplementary Material

ABBREVIATIONS:

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- FTD

frontotemporal lobe dementia

- LBD

Lewy body dementia

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- PD

Parkinson disease

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Stockholm County Council, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Swedish Dementia Association.

References

- 1. Haller S, Garibotto V, Kövari E, et al. Neuroimaging of dementia in 2013: what radiologists need to know. Eur Radiol 2013;23:3393–404 10.1007/s00330-013-2957-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKeith I. Dementia with Lewy bodies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2004;6:333–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McVeigh C, Passmore P. Vascular dementia: prevention and treatment. Clin Interv Aging 2006;1:229–35 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.3.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. ; Consortium on DLB. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863–72 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mrak RE, Griffin WS. Dementia with Lewy bodies: definition, diagnosis, and pathogenic relationship to Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2007;3:619–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mak E, Su L, Williams GB, et al. Neuroimaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6:18 10.1186/alzrt248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brown RK, Bohnen NI, Wong KK, et al. Brain PET in suspected dementia: patterns of altered FDG metabolism. Radiographics 2014;34:684–701 10.1148/rg.343135065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Binnewijzend MA, Kuijer JP, Benedictus MR, et al. Cerebral blood flow measured with 3D pseudocontinuous arterial spin-labeling MR imaging in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: a marker for disease severity. Radiology 2013;267:221–30 10.1148/radiol.12120928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Brien JT, Firbank MJ, Davison C, et al. 18F-FDG PET and perfusion SPECT in the diagnosis of Alzheimer and Lewy body dementias. J Nucl Med 2014;55:1959–65 10.2967/jnumed.114.143347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kwon DH, Kim JM, Oh SH, et al. Seven-Tesla magnetic resonance images of the substantia nigra in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 2012;71:267–77 10.1002/ana.22592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwarz ST, Afzal M, Morgan PS, et al. The “swallow tail” appearance of the healthy nigrosome: a new accurate test of Parkinson's disease—a case-control and retrospective cross-sectional MRI study at 3T. PLoS One 2014;9:e93814 10.1371/journal.pone.0093814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim E, et al. Loss of nigral hyperintensity on 3 Tesla MRI of parkinsonism: comparison with (123) I-FP-CIT SPECT. Mov Disord 2016;31:684–92 10.1002/mds.26584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim JM, Jeong HJ, Bae YJ, et al. Loss of substantia nigra hyperintensity on 7 Tesla MRI of Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016;26:47–54 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blazejewska AI, Schwarz ST, Pitiot A, et al. Visualization of nigrosome 1 and its loss in PD: pathoanatomical correlation and in vivo 7 T MRI. Neurology 2013;81:534–40 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829e6fd2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain 1991;114(pt 5):2283–301 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Damier P, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, et al. The substantia nigra of the human brain, I: nigrosomes and the nigral matrix, a compartmental organization based on calbindin D(28K) immunohistochemistry. Brain 1999;122(pt 8):1421–36 10.1093/brain/122.8.1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Damier P, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, et al. The substantia nigra of the human brain, II: patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson's disease. Brain 1999;122(pt 8):1437–48 10.1093/brain/122.8.1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haller S, Fällmar D, Larsson EM. Susceptibility weighted imaging in dementia with Lewy bodies: will it resolve the blind spot of MRI? Neuroradiology 2016;58:217–18 10.1007/s00234-015-1605-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shams S, Martola J, Granberg T, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: different prevalence, topography, and risk factors depending on dementia diagnosis—the Karolinska Imaging Dementia Study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:661–66 10.3174/ajnr.A4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shams S, Granberg T, Martola J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid profiles with increasing number of cerebral microbleeds in a continuum of cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36:621–28 10.1177/0271678X15606141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1995;57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meijer FJ, Steens SC, van Rumund A, et al. Nigrosome-1 on susceptibility weighted imaging to differentiate Parkinson's disease from atypical parkinsonism: an in vivo and ex vivo pilot study. Pol J Radiol 2016;81:363–69 10.12659/PJR.897090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamagata K, Nakatsuka T, Sakakibara R, et al. Diagnostic imaging of dementia with Lewy bodies by susceptibility-weighted imaging of nigrosomes versus striatal dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography: a retrospective observational study. Neuroradiology 2017;59:89–98 10.1007/s00234-016-1773-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zecca L, Casella L, Albertini A, et al. Neuromelanin can protect against iron-mediated oxidative damage in system modeling iron overload of brain aging and Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem 2008;106:1866–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beauchet O, Allali G, Berrut G, et al. Gait analysis in demented subjects: interests and perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2008;4:155–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cosottini M, Frosini D, Pesaresi I, et al. Comparison of 3T and 7T susceptibility-weighted angiography of the substantia nigra in diagnosing Parkinson disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:461–66 10.3174/ajnr.A4158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.