SUMMARY:

Animal models are necessary to develop and test innovations in aneurysm therapy before clinical introduction. This review aims at identifying the most likely candidates for standardizing preclinical testing of aneurysm devices. We systematically searched electronic databases for publications on animal aneurysm models from 1961–2008 to assess the methodologic quality of the studies and collect data on the patency and angiographic and pathologic outcomes of treatments. There has been a steady increase in the annual number of publications with time. Species that were most frequently used were dogs, rabbits, and rodents, followed by swine. Most publications are single-laboratory studies with variables and poorly validated outcome measures, a small number of subjects, and limited standardization of techniques. The most appropriate models to test for recurrences after endovascular occlusion were the surgical bifurcation model in dogs, and the elastase-induced aneurysm model in rabbits. A standardized multicenter study is needed to improve the preclinical evaluation of endovascular devices in aneurysm therapy.

Therapeutic innovations carry with them the promise of new treatments as well as the fear of new adverse events. Some form of preclinical screening test is necessary to minimize the risks for patients and to limit large-scale clinical investigations to the most promising devices. If initial development often involves in vitro experiments and bench testing, the last steps of device assessment before clinical introduction must take into account the complexity of the in vivo environment. Animal models are used for that purpose.

Naturally occurring intracranial aneurysms are rare in laboratory animals. Therefore, various models have been designed in many species, including mice, rats, rabbits, swine, sheep, dogs, and primates. Each model has advantages and limitations, and the choice will depend on the purpose. Experimental aneurysm models can be used for the following: 1) understanding the mechanisms involved in the initiation, progression, and rupture of aneurysms; 2) testing endovascular devices; and 3) training interventionists.

Using a variety of physiologic and pathologic manipulations, such as carotid ligation, renovascular hypertension, and lathyrism in rodents and primates, Hashimoto et al1 developed 1 model that closely resembled the morphologic, histologic, and hemodynamic features of human intracranial aneurysms. One advantage of this model is the induction of cerebral aneurysms without direct manipulation of intracranial arteries.2 These models could offer insight into the potential efficacy of pharmaceutical prevention of aneurysm formation and improved understanding of aneurysmal growth. However, the small size of aneurysms in mice and rats render these models inappropriate for the testing of endovascular interventions.

Murine models are useful for looking into the biology of arterial aneurysms, far beyond what can be achieved in large animals, thanks to the availability of sophisticated molecular and cellular techniques, including a wide array of genetically modified mice strains. An effort to retain these advantages in testing human devices has led some teams to construct aneurysms on the lateral wall of the abdominal aorta of rats or mice by using microsurgical techniques,3 and others to simplify models by eliminating the need for an aneurysm altogether and studying the direct implantation of coils into normal arteries4,5 or stents and flow diverters to determine branch preservation. Even though simpler designs such as arterial occlusion models can provide important insight regarding fundamental vascular phenomena, such as recanalization after coil embolization,5,6 they cannot comprehensively anticipate the potential advantages and complications related to the use of devices in human aneurysms. Hence, the development and refinement of new endovascular therapies have mostly relied on larger aneurysm models such as those in rabbits, swine, and canines,7–11 induced by vessel ligations combined with enzymatic injury or surgically constructed from autologous venous pouches. These larger models will be the focus of this review.

Inspired by the pioneering work of German and Black (1954),12 surgical constructions in rabbits, swine, and dogs varied in complexity, from lateral wall types by end-to-side suturing of a segment of vein to carotid arteries,13–15 to bifurcation aneurysms, anastomosing the right and left carotid arteries at the site of venous pouch implantation.8,16–19 (For a review, see Massoud et al 1994.20) The elastase-induced aneurysm model, most frequently used in rabbits,21,22 has been modified in various ways.23,24 Our aim was to review in the literature the main features of these models and their strengths and weaknesses in an effort to identify those that could serve as the most appropriate final assessor of new aneurysm devices immediately before clinical use. We paid special attention to models assessing coil embolization.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

We performed a computerized search strategy of Medline/PubMed (1961–2008) and EMBASE (1980–2008) for reports on animal models of aneurysms. We used the following keywords: aneurysm, saccular aneurysm, intracranial aneurysm, experimental aneurysm, animal models, swine, rabbit, dog, primate, mice, and rat in different combinations (by using the Boolean operator OR in conjunction with the Boolean operator AND). We performed a hand search in journals not indexed in PubMed and in bibliographies of included articles and review articles for additional studies. This method of cross-reference checking was continued until no further publications were found. We included studies that met all of the following criteria: 1) peer-reviewed articles, 2) original studies (not a letter, review article, conference abstract, or editorial), 3) English or French language, 4) a treatment (stents, coils, embolic agent) performed, 5) minimum number of 5 aneurysms, 6) minimal follow-up of 2 weeks, and 7) angiographic or pathologic outcomes.

The second author (O.N.) independently assessed the reproducibility of the search strategy and the eligibility of studies. In the case of disagreement, both observers (F.B. and O.N.) reviewed the article in question together until a consensus was reached.

Data were extracted to a data sheet, including the following: publication (first author's name, URL), aim of the study, species, the number of animals/aneurysms, aneurysm induction, outcomes, follow-up, compliance with animal welfare regulations, and embolization technique.

General Characteristics and Angiographic and Pathologic Outcomes

The absence of standardized end points precluded a meta-analysis. We collected general characteristics of the models (aneurysm size, neck morphology, patency of untreated aneurysms, angiographic occlusion rates, histologic techniques, and surgical complications) as claimed by the authors of the various source articles, and the results are given as a narrative report with references, without an attempt at quantification and cross-comparison.

Quality Assessment

The methodologic quality of the studies was scored against the following criteria (1 point each)25: 1) compliance with regulations, 2) inclusion of a control groups, 3) aneurysm size, 4) long-term patency, 5) rate of occlusion/recurrences, 6) correlation between angiography and histology, 7) blinding of outcome assessment; 8) randomization; and 9) procedural complications. Results expressed as means ± standard error of the mean were compared with analysis of variance, by using P < .05 as significant.

Results

Description of Studies

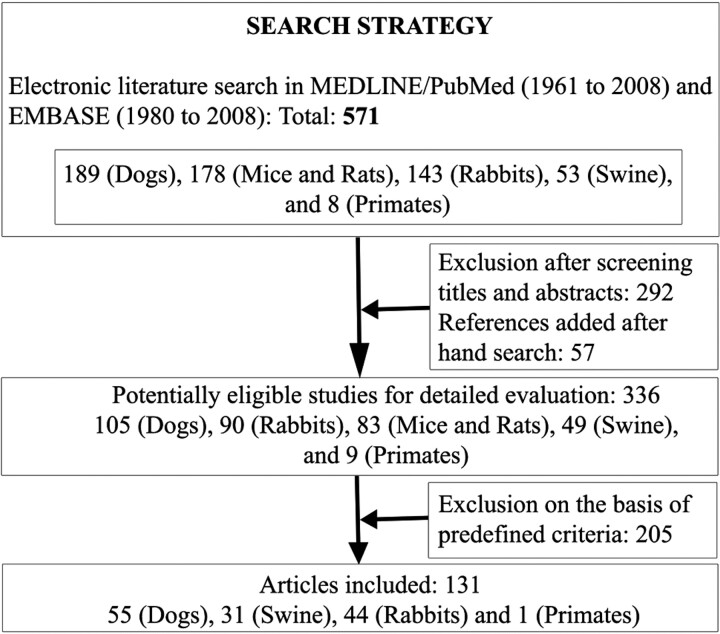

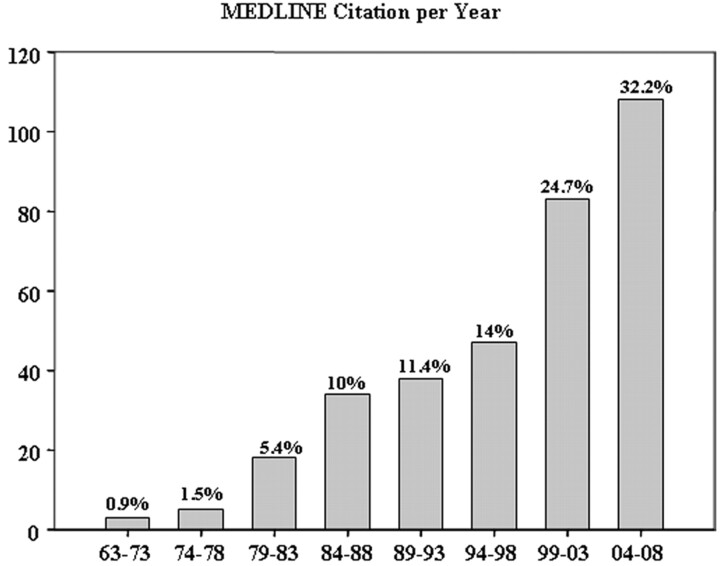

The initial search retrieved 571 publications (Fig 1). After viewing abstracts, we excluded 292 (51%); 57 articles were identified on hand searching of bibliographies and review articles, giving a total of 336 articles that were fully evaluated. We found an increasing number of articles per year published between 1961 and 2008 (Fig 2). Canine models were the most frequent (105 publications), followed by rabbits (90), rodents (83), swine (49), and primates (9).

Fig 1.

Search strategy and selection process for identifying articles on aneurysm models.

Fig 2.

Number of publications per year reporting intracranial aneurysm models, as recruited in electronic data bases, showing a threefold output in the 2000s compared with the decades from 1963 to 1993.

After examination of the full texts, we excluded 205 articles (61%) on the basis of selection criteria, yielding 131 studies. There were 55 reports on dogs, 31 on swine, 44 on rabbits, and 1 study on primates (Table 1). We identified 3 different models: lateral wall (82 studies; 2143 aneurysms, 57%); bifurcation (31 studies; 848 aneurysms, 22%); and elastase-induced aneurysms (27 studies; 794 aneurysms, 21%). In the 55 reports on dogs, 34 (62%) were on the lateral wall aneurysms, 12 (22%) were on bifurcation aneurysms, and 9 (16%) studies were about both. In the 44 studies on rabbits, 27 (61%) were on elastase-induced aneurysms, 7 (16%) on lateral wall aneurysms, and 10 (23%) on bifurcation aneurysms.

Table 1:

Number of each type of aneurysm per species in the final set of included studies (n = 131)

| Species (No. of Studies) | Lateral Wall, No. of Aneurysms (No. of Studies) | Bifurcation, No. of Aneurysms (No. of Studies) | Elastase, No. of Aneurysms (No. or % of Studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dogs (55) | 1051 (43)a | 442 (21)a | 0 |

| Swine (31) | 756 | 0 | 0 |

| Rabbits (44) | 313 (7) | 406 (10) | 794 (27) |

| Primates (1) | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2143 (57%) | 848 (22%) | 794 (21%) |

Nine studies reported both lateral wall and bifurcation aneurysms.

Quality of Studies

Methodologic domains that were most frequently respected are summarized in Table 2. Few studies used randomization or blind assessment of outcomes or attempted to correlate pathologic end points with angiographic outcomes. There was no difference in quality scores among the lateral wall (5.07 ± 0.19; n = 72), bifurcation (5.41 ± 0.22; n = 31), and elastase-induced aneurysm models (5.56 ± 0.27; n = 27) (P = .38).

Table 2:

Results of quality assessment of included studies

| Criteria | No. of Studies (%) (Total, 131) |

|---|---|

| Compliance with animal welfare regulations | 90 (70) |

| Control groups included | 91 (70) |

| Aneurysm size and morphology | 95 (73) |

| Patency of untreated aneurysms | 76 (59) |

| Angio and/or histologic scores | 117 (90) |

| Correlation between angio and histologic results | 34 (26) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | 27 (20) |

| Randomization of the experiment | 19 (15) |

| Surgery and procedural complications | 105 (81) |

General Characteristics

The main characteristics of the 5 most frequent models are summarized in on-line Table 1.

Surgical constructions were most frequent: 2991 (57%) of 3785 aneurysms were surgically created, while 794 (21%) elastase-induced aneurysms were recorded. Canine models were most frequently used; many desirable features, including reliable anesthesia, large vessels, and excellent long-term survival, were reported.7,11,17,19,26

Claims in favor of swine models included similarities to human physiology and coagulation systems; these models are commonly used in the field of cardiovascular research.27

Surgical constructions have been used in all species, most frequently the lateral wall model (n = 2143, 57%). Bifurcation models included many variants.19,28,29 The ability to vary the anatomy of the bifurcation, aneurysm size, neck size, and fundus-to-neck ratio is a potential advantage of surgical models.20

Creation of bifurcation aneurysms in rabbits is more difficult and perhaps less reliable, with a higher incidence of anesthesia-related deaths, procedure-related mortality, and parent vessel occlusions.8,30,31

The elastase model was limited to rabbits, with advantages of easy in handling and long-term survival with aneurysms followed for >5 years.32 With some training, the results seem to be reproducible. Limitations included the uncontrolled size of aneurysms (potentially corrected by adjusting the ligation site),33 sacrifice of the arterial access for each angiogram, and the small size of the animal, limiting the evaluation of large devices or techniques requiring multiple catheters.34

Angiographic Outcomes

The lack of spontaneous thrombosis is an important criterion for a good model. Natural history studies of untreated aneurysms are few, however. In swine, the patency of untreated aneurysm was evaluated in only 7/31 studies (22%); swine aneurysms, when left untreated, have a tendency for postoperative rupture or spontaneous thrombosis. This drawback necessitated immediate embolization following aneurysm construction.9,35 We noted spontaneous thrombosis between 2 and 7 weeks of lateral wall swine aneurysms (n = 5).13,35 Aneurysm patency was reported in 5/12 canine bifurcation aneurysm studies, in 6/9 on bifurcation and lateral wall aneurysms, and in 21/34 on lateral wall aneurysms. Canine lateral wall aneurysms may infrequently undergo thrombosis (<10%), but most aneurysms (90%) remained patent during a follow-up period of ≥7 months.36–38 Bifurcation aneurysms enlarge during the first several weeks.38 The incidence of spontaneous thrombosis is influenced by the ratio of the volume of the aneurysm to the area of the neck (ostium).12 Modifications of the ostium can also minimize thrombosis.26,39

In rabbits, 1/7 studies assessed the patency of surgically created lateral wall aneurysms, and 8/10, of bifurcation aneurysms. In the elastase model, 20/27 studies confirmed aneurysm patency. A long-term study showed neither spontaneous thrombosis nor significant change in dimensions 24 months after aneurysm creation.40

The standard method for the evaluation of the treatment is angiography. The occlusion and recanalization rates found after embolization will, of course, depend on the device targeted by the publication.

Coil embolization of swine aneurysms is routinely followed by progressive and finally complete occlusion.35 Residual necks and recurrences after coil embolization have been demonstrated in lateral wall aneurysms in dogs; however, recurrences are rare when lateral wall aneurysms are completely occluded initially.28 Bifurcation aneurysm models in dogs and rabbits can show recurrences with variable frequencies, despite treatment with various types of devices.12,13,16,28,41–43 Angiographic recurrences are rarely documented after coil embolization of the rabbit elastase aneurysms, but “microrecurrences” (only seen at pathology) are common.10,44,45

Pathologic Analyses of Treated Aneurysms

The pathology of aneurysms treated by embolization or stent placement is hampered by the presence of metallic or polymeric materials. One option is to embed the specimen in resins with the device in situ and resort to cutting-grinding thick sections, a method that precludes standard processing methods and advanced techniques such as immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence. An alternative is to carefully dissect the device from the tissues and use standard paraffin embedding. A variety of ways to circumvent these difficulties have been published,46–48 but high-quality analyses of early fragile specimens (within days after embolization), which could have been mechanistically revealing, often remain problematic. Studies reporting pathologic techniques are summarized in Table 3. In the 120 studies that included histologic findings, only 23 (19%) used a qualitative or semiquantitative grading system developed by the authors.

Table 3:

Number of studies reporting the different histologic techniques (tissue-processing procedure, conventional staining, IHC, SEM) and the use of scoring technique

| Species, Aneurysm (No. of studies) | Studies with Histology, No. (%)a | Plastic Inclusion, No. (%)b | Paraffin Inclusion, No. (%)b | Stains, No. (%)b | IHC, No. (%)b | SEM, No. (%)b | Scoring Technique, No. (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canine, lateral wall (43)c | 37 (86) | 15 (40) | 24 (65) | 37 (100) | 9 (24) | 12 (32%) | 4 (11) |

| Canine, bifurcation (21)c | 19 (90) | 8 (42) | 11 (58) | 19 (100) | 8 (42) | 4 (21%) | 2 (10) |

| Swine, lateral wall (31) | 26 (84) | 10 (38) | 19 (73) | 25 (96) | 8 (30) | 4 (15%) | 7 (27) |

| Rabbit, lateral wall (7) | 4 (57) | 0 | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 3 (75) | 1 (25%) | 0 |

| Rabbit, bifurcation (10) | 8 (80) | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 8 (100) | 1 (12) | 3 (37%) | 0 |

| Rabbit, elastase (27) | 26 (96) | 14 (54) | 17 (65) | 26 (100) | 5 (19) | 4 (15%) | 10 (38) |

| Total (139) | 120 (86) | 49 (41) | 81 (67.5) | 119 (99) | 34 (28) | 27 (22.5) | 23 (19) |

Percentage of studies in aneurysms of each animal species.

Percentage of studies with histology.

Nine studies reported on both lateral wall and bifurcation aneurysms.

A correlation between pathologic and angiographic outcomes has rarely been documented, except for canine bifurcation aneurysms.29,42,43 Among the 10 studies performed in bifurcation aneurysms in rabbits, 5 revealed a considerable discrepancy between radiologic and pathologic findings, with angiography overestimating the degree of occlusion in all cases.8,18,30,31 Microscopic recurrences have been described with the rabbit elastase model, but a correlation with angiographic recurrences is rarely possible.45,49,50

Nevertheless, characteristics of the healing of experimental aneurysms, mainly gleaned from cross-species comparisons, have been described. These studies have uniformly revealed organization of the thrombus within the aneurysmal sac within 6 months of platinum coil embolization of surgically created aneurysms in canines and swine, as well as neointimal coverage of the ostium of occluded aneurysms.7,51–53 The most frequent descriptions of coil embolization of aneurysms are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4:

Primary histopathologic findings after coil embolization of experimental aneurysms

| Species, Aneurysm | Neck | Dome | Reaction Around and Inside Coils | Inflammation Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canine, lateral wall7,41,52,57 | Neointima in the obliterated and recanalized aneurysms (170.00 ± 42.43 μm) | Variably organized connective tissue | Neointima and connective tissue tightly adhering to the coils | Minimal inflammatory reaction |

| Canine, bifurcation28,29,43,52 | Very thin neointima (29.80 ± 24.35 μm); frequent endothelialized clefts | Little-to-no residual thrombus; organized vascularized fibrocellular tissue | Coils apparently bare or covered by a neointimal membrane of variable thickness | Minimal degree of inflammation |

| Swine, lateral wall35,41,55,56 | Thick fibrous neointimal membrane >1000 μm | Dense fibrotic tissue | Neointima and connective tissue tightly adhering to the coils | Attenuated inflammatory reaction |

| Rabbit, bifurcation8,15,18,30,31 | No endothelialization | No evidence of organized thrombus | Uncovered coils in the lumen and no fibrosis between the loops of coils | Severe chronic or no major inflammatory reaction |

| Rabbit, elastase10,44–46,72 | Partial or complete thin neointimal coverage | Loose hypocellular vascularized connective tissue; no contractile cells and no collagen deposition | No endothelial layer covering the coils close to the aneurysm neck | Marked-to-mild localized chronic inflammatory infiltration |

Aneurysms in swine have a tendency to heal, with or without embolization and with any material.9,13,35,54,55 Early inflammatory changes39,54,55 were followed by a centripetal myofibroblast infiltration, robust collagen deposition, and a thick neointima, which completely sealed the neck.48 When all specimens showed permanent occlusions and favorable healing characteristics at some delayed time points, as seen in swine aneurysms, then some earlier timeframe was chosen, in hopes of detecting accelerated healing with some new material.56

In the long term, treated canine lateral wall aneurysms are completely occluded in most cases.7,41,51–53,57 Canine bifurcation aneurysms have a propensity for recurrences, however; therefore, they can reproduce the problem found in human aneurysms.41,54 Nevertheless, organization of thrombus was found at 4 weeks,57 whether aneurysms were occluded or showed early recurrences. At 3 months,28,29 recurrences were found, despite the presence of a neointimal layer that was continuous with the endothelialized clefts, which are thought to be involved in the recanalization process.

Rabbits seem to have a lesser propensity for healing. There was no endothelialization across the aneurysm orifice and no evidence of organized thrombus, but a thickened wall was associated with chronic31 or no major inflammatory reaction8 in bifurcation aneurysms.

Platinum coil embolization of rabbit elastase–induced aneurysms was followed by relatively poor healing, through thrombus formation, granulated tissue organization, and, finally, loose connective-tissue formation with no contractile cell infiltration. Deposition of collagen was absent, and tissue coverage at the neck was relatively poor.10,44,57

Discussion

The general ability of animal studies to predict future clinical success remains controversial. The debate has resurfaced recently with the repeated disappointments encountered in the development of drug therapies for stroke.58 It remains difficult to choose which promising device should be prioritized and which should be subjected to long and expensive clinical trials, without good quality preclinical studies. We have focused our study on models designed to assess endovascular devices, a modest objective compared with more fundamental research on the growth and rupture of aneurysms, for which most recent models would be deficient or inappropriate.

We believe that animal models remain grossly underused. Many endovascular devices in current clinical use have never been studied in published preclinical studies, and in the absence of randomized trials, many remain of unknown benefit. Animal studies have been more frequent in recent years, but there is no standardized testing required of an aneurysm device to be considered ready for a clinical application. Preclinical testing schemes typically include single-laboratory studies with various poorly validated outcomes and measures and small sample sizes. The main purpose of this review was to identify the best potential models that could serve such a standardizing role.

Some ideal features of a good aneurysm model include the following: minimal surgical and endovascular morbidity; similarity to human aneurysm shear stresses, hemodynamic forces, physical dimensions, perianeurysmal environment, and tissue responses; and stability without spontaneous thrombosis when untreated.59 None of the available models offer all these features.

Different animal models target different purposes. For example, swine models, widely used in cardiology circles, have been thoroughly validated to assess the risk of in-stent stenosis. The propensity of this species for thrombosis and neointima formation, particularly useful to assess arterial stenoses after device implantation,27 makes this model ill-fitted for discriminating the capacity of aneurysm-treatment devices to prevent recanalization or induce permanent occlusions. Reproducing the clinical problem that innovations are designed to address is a fundamental requirement of a model. Hence, lateral wall models in general, and swine models in particular, cannot predict the ability of new coils to improve long-term angiographic results.28,35

Two models have repeatedly proved valuable in the assessment of aneurysmal devices: the canine bifurcation model and the rabbit elastase model. These models have not been thoroughly evaluated for repeatability of results between centers however. Future collaborative work should concentrate on this issue.

Any meaningful research must involve comparison between 2 treatments by using some end point criteria. Angiographic outcomes at 3 or 6 months can be compared in the canine bifurcation aneurysm models, and with such end points, the value of 1 embolic device over another was shown in the past.19,43,60 We must remember that even if better angiographic results in animals could be shown to predict better angiographic results in humans, these end points are surrogates for long-term efficacy in the prevention of ruptures.

The investigation of histologic phenomena that follow embolization has often been purely descriptive, but the meaning of these observations and their clinical relevance remain obscure when findings are not correlated, if not causally related, to a comparison between aneurysms that recur and those that do not.61 In the absence of an explanatory correlation between angiographic evolutions and pathologic findings, researchers have relied on a priori principles inspired from analogies with other vascular research fields. For example, incorporation into the vessel wall and neointima formation on stents, grafts, and stent-grafts62 have played a dominant role in the concept of healing after device implantation. Another potential justification for using pathologic findings as surrogate end points is human autopsy findings. Data on humans are quite limited.63–67 However, enduring occlusions after platinum coiling have been associated with neointimal closure of the neck and organization of the clot within the aneurysmal sac,67 while incomplete occlusions and recanalized aneurysms have been associated with unorganized thrombus and poor cellularity at the implant/parent artery interface.68 Many investigators have published scales that offer a rational, if not a validated basis, for assessing the performance of an implant, by giving points for features considered favorable for healing, including neck coverage with neointima, thickness of neointimal layer, or clot organization at the dome.11,19,43–47,56,69 These semiquantitative scales have largely been confined to single-center experiences; they have not been reproduced or validated. No one, to our knowledge, has been able to show that these criteria predict better in vivo clinical performances, however. Finally, the absence of a proved link between the biologic responses of these models with those found in human aneurysms must be emphasized.

Conclusions

Currently, available animal models present multiple weaknesses, but preclinical testing of new devices remains a necessity. Candidate models most appropriate for this preclinical evaluation include the rabbit elastase and the canine bifurcation aneurysm models.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- Angio

angiography

- ICA

intracranial aneurysms

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- SEM

scanning electron microscope

- w

width

Footnotes

Indicates article with supplemental on-line table.

References

- 1. Hashimoto N, Handa H, Nagata I, et al. Animal model of cerebral aneurysms: pathology and pathogenesis of induced cerebral aneurysms in rats. Neurol Res 1984;6:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morimoto M, Miyamoto S, Mizoguchi A, et al. Mouse model of cerebral aneurysm: experimental induction by renal hypertension and local hemodynamic changes. Stroke 2002;33:1911–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frosen J, Marjamaa J, Myllarniemi M, et al. Contribution of mural and bone marrow-derived neointimal cells to thrombus organization and wall remodeling in a microsurgical murine saccular aneurysm model. Neurosurgery 2006;58:936–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raymond J, Lebel V, Ogoudikpe C, et al. Recanalization of arterial thrombus, and inhibition with beta-radiation in a new murine carotid occlusion model: MRNA expression of angiopoietins, metalloproteinases, and their inhibitors. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:1190–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abrahams JM, Forman MS, Grady MS, et al. Biodegradable polyglycolide endovascular coils promote wall thickening and drug delivery in a rat aneurysm model. Neurosurgery 2001;49:1187–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yasuda H, Kuroda S, Nanba R, et al. A novel coating biomaterial for intracranial aneurysms: effects and safety in extra- and intracranial carotid artery. Neuropathology 2005;25:66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mawad ME, Mawad JK, Cartwright J, et al. Long-term histopathologic changes in canine aneurysms embolized with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:7–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reul J, Weis J, Spetzger U, et al. Long-term angiographic and histopathologic findings in experimental aneurysms of the carotid bifurcation embolized with platinum and tungsten coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:35–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murayama Y, Vinuela F, Suzuki Y, et al. Development of the biologically active Guglielmi detachable coil for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Part II. An experimental study in a swine aneurysm model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:1992–99 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kallmes DF, Fujiwara NH, Yuen D, et al. A collagen-based coil for embolization of saccular aneurysms in a New Zealand white rabbit model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:591–96 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raymond J, Guilbert F, Metcalfe A, et al. Role of the endothelial lining in recurrences after coil embolization: prevention of recanalization by endothelial denudation. Stroke 2004;35:1471–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. German W, Black S. Experimental production of carotid aneurysms. N Engl J Med 1954;250:104–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guglielmi G, Ji C, Massoud TF, et al. Experimental saccular aneurysms. II. A new model in swine. Neuroradiology 1994;36:547–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bavinzski G, al-Schameri A, Killer M, et al. Experimental bifurcation aneurysm: a model for in vivo evaluation of endovascular techniques. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 1998;41:129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bavinzski G, Richling B, Binder BR, et al. Histopathological findings in experimental aneurysms embolized with conventional and thrombogenic/antithrombolytic Guglielmi coils. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 1999;42:167–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Forrest MD, O'Reilly GV. Production of experimental aneurysms at a surgically created arterial bifurcation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1989;10:400–02 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strother CM, Graves VB, Rappe A. Aneurysm hemodynamics: an experimental study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1992;13:1089–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spetzger UJ, Reul J, Weis J. Endovascular coil embolization of microsurgically produced experimental bifurcation aneurysms in rabbits. Surg Neurol 1998;49:491–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Raymond J, Salazkin I, Georganos S, et al. Endovascular treatment of experimental wide neck aneurysms: comparison of results using coils or cyanoacrylate with the assistance of an aneurysm neck bridge device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:1710–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Massoud TF, Guglielmi G, Ji C, et al. Experimental saccular aneurysms. I. Review of surgically-constructed models and their laboratory applications. Neuroradiology 1994;36:537–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cloft HJ, Altes TA, Marx WF, et al. Endovascular creation of an in vivo bifurcation aneurysm model in rabbits. Radiology 1999;213:223–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Altes TA, Cloft HJ, Short JG, et al. 1999 ARRS Executive Council Award: creation of saccular aneurysms in the rabbit—a model suitable for testing endovascular devices. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krings T, Moller-Hartmann W, Hans FJ, et al. A refined method for creating saccular aneurysms in the rabbit. Neuroradiology 2003;45:423–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoh BL, Rabinov JD, Pryor JC, et al. A modified technique for using elastase to create saccular aneurysms in animals that histologically and hemodynamically resemble aneurysms in humans. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146:705–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Macleod MR, O'Collins T, Howels DW, et al. Pooling of animal experimental data reveals influence of study design and publication bias. Stroke 2004;35:1203–08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shin YS, Niimi Y, Yoshino Y, et al. Creation of four experimental aneurysms with different hemodynamics in one dog. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1764–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kantor B, Ashai K, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. The experimental animal models for assessing treatment of restenosis. Cardiovasc Radiat Med 1999;1:48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raymond J, Berthelet F, Desfaits AC, et al. Cyanoacrylate embolization of experimental aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:129–38 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raymond J, Darsaut T, Salazkin Y, et al. Mechanisms of occlusion and recanalization in canine carotid bifurcation aneurysms embolized with platinum coils: an alternative concept. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:745–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spetzger U, Reul J, Weis J, et al. Microsurgically produced bifurcation aneurysms in a rabbit model for endovascular coil embolization. J Neurosurg 1996;85:488–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Böcher-Schwarz HG, Ringel K, Bohl J, et al. Histological findings in coil-packed experimental aneurysms 3 months after embolization. Neurosurgery 2002;50:379–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lewis DA, Ding YH, Dai D, et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with creation of elastase-induced saccular aneurysms in a rabbit model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009;30:91–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ding YH, Dai D, Danielson MA, et al. Control of aneurysm volume by adjusting the position of ligation during creation of elastase-induced aneurysms: a prospective study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:857–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ding YH, Danielson MA, Kadirvel R, et al. Modified technique to create morphologically reproducible elastase-induced aneurysms in rabbits. Neuroradiology 2006;48:528–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Byrne JV, Hope JK, Hubbard N, et al. The nature of thrombosis induced by platinum and tungsten coils in saccular aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:29–33 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kallmes DF, Altes TA, Vincent DA, et al. Experimental side-wall aneurysms: a natural history study. Neuroradiology 1999;41:338–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turk AS, Aagaard-Kienitz B, Niemann D, et al. Natural history of the canine vein pouch aneurysm model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:531–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsumoto T, Song JK, Niimi Y, et al. Interval change in size of venous pouch canine bifurcation aneurysms over a 10-month period. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1067–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yoshino Y, Niimi Y, Song JK, et al. Preventing spontaneous thrombosis of experimental sidewall aneurysms: the oblique cut. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1363–65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ding YH, Dai D, Lewis DA, et al. Long-term patency of elastase-induced aneurysm model in rabbits. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:139–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raymond J, Desfaits AC, Roy D. Fibrinogen and vascular smooth muscle cell grafts promote healing of experimental aneurysms treated by embolization. Stroke 1999;30:1657–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Song JK, Niimi Y, Yoshino Y, et al. Assessment of Matrix coils in a canine model of a large bifurcation aneurysm. Neuroradiology 2007;49:231–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Turk AS, Luty CM, Carr-Brendel V, et al. Angiographic and histological comparison of canine bifurcation aneurysms treated with first generation Matrix and standard GDC coils. Neuroradiology 2008;50:57–65. Epub 2007 Sep 27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dai D, Ding YH, Lewis DA, et al. A longitudinal immunohistochemical study of the healing of experimental aneurysms after embolization with platinum coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:736–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krings T, Busch C, Sellhaus B, et al. Long-term histological and scanning electron microscopy results of endovascular and operative treatments of experimentally induced aneurysms in the rabbit. Neurosurgery 2006;59:911–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dai D, Ding YH, Danielson MA, et al. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical comparison of human, rabbit, and swine aneurysms embolized with platinum coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:2560–68 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dai D, Ding YH, Danielson MA, et al. Modified histologic technique for processing metallic coil-bearing tissue. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1932–36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kadirvel R, Dai D, Ding YH, et al. Endovascular treatment of aneurysms: healing mechanisms in a swine model are associated with increased expression of Matrix metalloproteinases, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor, and decreased expression of tissue inhibitors of Matrix metalloproteinases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:849–56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hans FJ, Moller-Hartmann W, Brunn A, et al. Treatment of wide-necked aneurysms with balloon-expandable polyurethane-covered stentgrafts: experience in an animal model. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:871–76. Epub 2005 Mar 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dai D, Ding YH, Lewis DA, et al. A proposed ordinal scale for grading histology in elastase-induced, saccular aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:132–38 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tenjin H, Fushiki S, Nakahara Y, et al. Effect of Guglielmi detachable coils on experimental carotid artery aneurysms in primates. Stroke 1995;26:2075–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Macdonald RL, Mojtahedi S, Johns L, et al. Randomized comparison of Guglielmi detachable coils and cellulose acetate polymer for treatment of aneurysms in dogs. Stroke 1998;29:478–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Sepetka I, et al. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach. Part 1. Electrochemical basis, technique, and experimental results. J Neurosurg 1991;75:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Raymond J, Venne D, Allas S, et al. Healing mechanisms in experimental aneurysms. I. Vascular smooth muscle cells and neointima formation. J Neuroradiol 1999;26:7–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee D, Yuki I, Murayama Y, et al. Thrombus organization and healing in the swine experimental aneurysm model. Part I. A histological and molecular analysis. J Neurosurg 2007;107:94–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Murayama Y, Tateshima S, Gonzalez NR, et al. Matrix and bioabsorbable polymeric coils accelerate healing of intracranial aneurysms: long-term experimental study. Stroke 2003;34:2031–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cruise GM, Shum JC, Plenck H. Hydrogel-coated and platinum coils for intracranial aneurysm embolization compared in three experimental models using computerized angiographic and histologic morphometry. J Mater Chem 2007;17:3965–73 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Donnan GA, Davis SM. Stroke drug development: usually, but not always, animal models. Stroke 2005;36:23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Massoud TF, Ji C, Guglielmi G, et al. Experimental models of bifurcation and terminal aneurysms: construction techniques in swine. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:938–44 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yoshino Y, Niimi Y, Song J, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms: comparative evaluation in a terminal bifurcation aneurysm model in dogs. J Neurosurg 2004;101:996–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Raymond J, Salazkin I, Gevry G, et al. Interventional neuroradiology: the role of experimental models in scientific progress. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:401–05 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lerouge S, Raymond J, Salazkin I, et al. Endovascular aortic aneurysm repair with stent-grafts: experimental models can reproduce endoleaks. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004;15:971–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Molyneux A, Ellison D, Morris J, et al. Histological findings in giant aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils: report of two cases with autopsy correlation. J Neurosurg 1995;83:129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Castro E, Fortea F, Villoria F. Long-term histopathologic findings in two cerebral aneurysms embolized with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999;20:549–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ishihara S, Mawad M, Ogata K. Histopathologic findings in human cerebral aneurysms embolized with platinum coils: report of two cases and review of the literature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:970–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Groden C, Hagel C, Delling G, et al. Histological findings in ruptured aneurysms treated with GDCs: six examples at varying times after treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:579–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bavinzski GT, Killer M, Talazoglu V, et al. Gross and microscopic histopathological findings in aneurysms of the human brain treated with Guglielmi detachable coils. J Neurosurg 1999;91:284–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Molyneux A, Stratton I, Sandercock P, et al. , for the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Collaborative Group. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hino K, Konishi Y, Shimada A, et al. Morphologic changes in neo-intimal proliferation in an experimental aneurysm after coil embolization: effect of factor XIII administration. Neuroradiology 2004;46:996–1005. Epub 2004 Nov 5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moller-Hartmann W, Krings T, Stein KP, et al. Aberrant origin of the superior thyroid artery and the tracheoesophageal branch from the common carotid artery: a source of failure in elastase-induced aneurysms in rabbits. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:739–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Thiex R, Hans FJ, Krings T, et al. Haemorrhagic tracheal necrosis as a lethal complication of an aneurysm model in rabbits via endoluminal incubation with elastase. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146:285–89. Epub 2004 Jan 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Roth C, Struffert T, Grunwald I, et al. Long-term results with Matrix coils vs. GDC: an angiographic and histopathological comparison. Neuroradiology 2008;50:693–99. Epub 2008 May 29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.