SUMMARY:

Our purpose was to use multiple inflow pulsed ASL to investigate whether hemodynamic AAT information is sensitive to hemispheric asymmetry in acute ischemia. The cohorts included 15 patients with acute minor stroke or TIA and 15 age-matched controls. Patients were scanned by using a stroke MR imaging protocol at a median time of 74 hours. DWI lesion volumes were small and functional impairment was low; however, perfusion abnormalities were evident. Prolonged AAT values were more likely to reside in the affected hemisphere (significant when compared with controls, P < .048). An advantage of this ASL technique is the ability to use AAT information in addition to CBF to characterize ischemia.

ASL is a noninvasive MR imaging technique capable of providing perfusion information without the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents. ASL relies on contrast by magnetically labeling blood water and detecting the signal intensity as a tracer bolus; it has shown promise in clinical studies involving acute stroke1,2 and ICA occlusion.3,4 The shortcomings of the ASL techniques include the following: 1) limited brain coverage, 2) low signal intensity–to-noise ratio, and 3) accounting for delays in AAT (the time duration for blood to move from tagging to imaging locations). The current study attempts to address each of these issues.

An acute cerebrovascular event may increase the AAT by the following mechanisms: Labeled blood must travel via either collateral pathways of the circle of Willis or secondary collateral pathways, such as those that are provided by leptomeningeal vessels. Labeled blood that remains in the large-vessel intravascular space at the time of imaging, due to an insufficient postlabel delay as in continuous ASL or an insufficient TI as in pulsed ASL, will affect the CBF image.2 A recent ICA occlusion study highlighted the relevance of AAT in clinical perfusion ASL.5 The goal in the current study is to demonstrate the clinical utility of a whole-brain 3D-GRASE-PASL implementation with multiple-inflow periods to derive maps of CBF and AAT in patients with minor stroke/TIA. Analogous to hemodynamic timing parameters used in DSC perfusion for acute stroke diagnosis, AAT maps, hypothetically, can be used to characterize the extent of perfusion abnormalities.

Technique

MR imaging data were collected on a 3T scanner (Tim Trio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 12-channel head receive coil in a 2-cohort study: 1) 15 patients with acute minor stroke or TIA, and 2) 15 age-matched controls. Carotid Doppler sonography was performed on patients only. Relevant sequences in the protocol were the following: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, DWI, and pulsed ASL with flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery preparation6 and a 3D GRASE readout.7 3D-GRASE-PASL data were collected at 9 inflow times (TI: start = 500 ms, end = 2500 ms, increments = 250 ms; imaging volume: 200 × 200 × 120 mm3; 64 × 64 × 24 matrix; voxel dimensions: 3.1 × 3.1 × 5.0 mm3; TR/TE = 3156/39.9 ms). ASL parameters for patients were 8 controls/tags, 9 TIs, and 7:30 scan duration. ASL parameters for the age-matched healthy cohort were 11 controls/tags, 11 TIs, and 11:30 scan duration.

ASL images were spatially smoothed (full width at half maximum = 6 mm). Difference images were averaged at each TI, producing an ASL kinetic curve to which a 2-parameter model8 was fit for each voxel by using least squares in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts), and fit confidence intervals were analyzed for CBF and AAT. Units for AAT are output as seconds, while CBF milliliters per 100 grams of tissue per minute quantification requires additional steps, as described elsewhere.9

AAT patterns were characterized in the age-matched cohort to create an expected distribution. It has recently been shown that AAT varies regionally and is correlated with brain volume and sex in young adults.10 AAT patterns are defined by the vascular territories,11 and we surmise that AAT is age-dependent, thus the motivation for the age-matched cohort. AAT maps were analyzed in Talairach coordinate space. Absolute AAT depends on the thickness of the imaging volume, but relative differences between brain regions or hemispheres are independent of imaging parameters. Therefore, an asymmetry metric was devised to compare the distribution of AAT values in the affected and unaffected hemispheres. The AAT asymmetry index was calculated by using the AAT area AUH (AATAUH in the affected hemisphere − AATAUH in the unaffected hemisphere) / (total AATAUH). A positive index indicates prolonged AAT in the affected hemisphere (asymmetry range: −1 to 1). A similar index was devised for controls by using (left AATAUH − right AATAUH) / total AATAUH. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was used to compare AAT hemispheric asymmetry between patients and controls.

Discussion

Tables 1 and 2 show demographic data for the 15 patients. DWI lesion volumes were small (median volume = 0.9 mL; range = 0–49 mL), consistent with the clinically minor strokes in this group.12 Mean NIHSS score was 1 ± 2. There was no significant difference in age between cohorts (patients = 74 ± 11 years, controls = 69 ± 5 years; P = .24).

Table 1:

Patient demographics with diagnoses

| Patient No. | Sex | Age (yr) | Carotid Stenosis (%) |

DWI (mL) | NIHSS Score | Barthel Indexb | Time to Scan (hr)a | Clinical Diagnosis | Report (Outcome) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | |||||||||

| 1 | F | 48 | 96 | 0 | 49.10 | 1 | 100 | 104 | Stroke | Left frontal embolic |

| 2 | M | 66 | 15 | 0 | 6.10 | 3 | 60 | 17 | Stroke | Left embolic MCA |

| 3 | M | 85 | 0 | 100 | 6.25 | 3 | 50 | 103 | Stroke | Right embolic |

| 4 | M | 81 | 70 | 30 | 3.21 | 1 | 90 | 72 | Stroke | Right embolic |

| 5 | M | 92 | 50 | 30 | 1.56 | 0 | 90 | 74 | Stroke | Left subcortical |

| 6 | M | 70 | 30 | 0 | 0.89 | 0 | 100 | 194 | TIA | Left, unknown etiology |

| 7 | M | 71 | 50 | 10 | 0.00 | 0 | 100 | 45 | TIA | DWI negative, no lesion |

| 8 | M | 81 | 60 | 40 | 0.76 | 0 | 55 | 60 | Stroke | Left cortical |

| 9 | F | 70 | 65 | 35 | 0.73 | 0 | 100 | 44 | TIA | Right frontal embolic |

| 10 | M | 69 | 65 | 100 | 5.97 | 1 | 95 | 96 | Stroke | Left frontal embolic |

| 11 | F | 68 | 10 | 70 | 0.00 | 0 | 100 | 112 | TIA | DWI negative, no lesion |

| 12 | M | 79 | 60 | 90 | 0.46 | 0 | 100 | 44 | Stroke | Right embolic MCA |

| 13 | M | 82 | 70 | 30 | 0.48 | 0 | 100 | 68 | Stroke | Left embolic MCA |

| 14 | M | 62 | 40 | 70 | 0.86 | 1 | 100 | 143 | Stroke | Left thalamic |

| 15 | M | 84 | 45 | 50 | 4.21 | 6 | 55 | 131 | Stroke | Right frontal embolic |

Time to scan is the time in hours from symptom onset to MR imaging.

Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living

Table 2:

Patient statisticsa

| Statistics | Age (yr) | DWI (mL) | NIHSS Score | Barthel Indexb | Time to Scan (hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 74 | 5.4 | 1 | 86 | 87 |

| Minimum | 48 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 17 |

| Maximum | 92 | 49 | 6 | 100 | 194 |

| Median | 71 | 0.9 | 0 | 100 | 74 |

| SD | 11 | 12.3 | 2 | 20 | 46 |

Time to scan is the time in hours from symptom onset to MR imaging.

Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living

Figure 1 shows the DWI, CBF (milliliters per 100 grams per minute), and AAT (seconds) maps for 3 patients scanned acutely, ordered with decreasing DWI lesion volumes. Patient 1 had a large DWI infarct despite an NIHSS score of 1. The corresponding CBF and AAT maps show regions of hypoperfusion and delayed AAT in the affected hemisphere. Patients 12 and 9 had small DWI infarcts. While Patient 12 has regions of pronounced AAT delay, findings on CBF and AAT maps for patient 9 are relatively normal.

Fig 1.

Acute images for 3 patients with decreasing infarct volumes. Patient 1 shows a delayed AAT region (hyperintensity) in the affected hemisphere, where CBF is reduced (hypointensity). Patient 12 shows reduced CBF in the affected hemisphere and delayed AAT, while maps for Patient 9 have normal findings. Abnormal CBF and AAT regions are outlined in red.

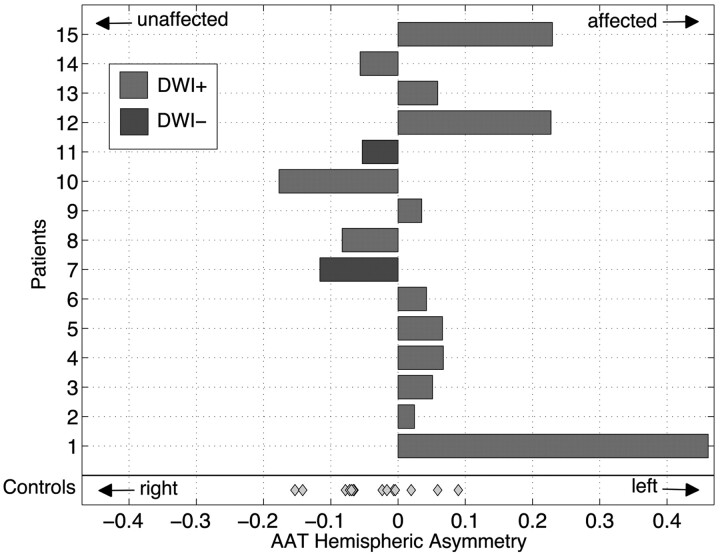

Figure 2 shows AAT asymmetry data for patients and controls. The control cohort demonstrates a symmetric AAT hemispheric index that is centered near zero with low variance. Patient AAT hemispheric metrics favor the affected hemisphere, suggesting prolonged AAT, and are significantly different compared with those in controls (P < .048).

Fig 2.

AAT hemispheric asymmetry index is displayed as a bar plot for each patient. Control cohort data are more symmetric about zero with less variance. Patient data are significantly different from those of controls (P < .048). Light gray indicates DWI-positive; dark gray, DWI-negative; diamond datum, control participant.

A whole-brain noninvasive ASL technique capable of mapping CBF and AAT in patients with minor stroke/TIA is presented. CBF data were consistent with previous ASL studies.2,3 Our PASL acquisition, however, was designed as a bolus-tracking experiment and provided evidence that AAT can be used to characterize perfusion abnormalities.

CBF and AAT maps revealed asymmetric perfusion patterns in some patients, defined by delayed AAT in patients in whom acute symptoms were minor or had resolved. This result is not unexpected because previous studies have shown perfusion deficits in 32% of patients with TIA.13 This technical report demonstrates the feasibility of multi-TI PASL in acute stroke and provides support for future efforts to characterize longitudinal changes.

There are 2 main advantages of this multi-TI 3D-GRASE-PASL: 1) whole-brain coverage allowing visualization of perfusion patterns in patients with only a small embolic infarct in superior regions (eg, patient 9), and 2) calculation of AAT, with a temporal resolution of 250 ms. Others have reported previously that AAT artifacts were found in 7 of 15 patients due to an insufficient postlabeling delay in some patients when using continuous ASL.2 This issue is minimized in the current study because both CBF and AAT are estimated.

There are some important caveats: 1) Stroke may result in an AAT that is beyond the maximum TI in the current study (ie, AATmax = 2500 ms), 2) The presence of large-vessel atherosclerosis likely influenced our AAT estimates. In DSC perfusion MR imaging, timing parameters are often used to delineate perfusion deficits, though they tend to overestimate the ischemic region. It is conceivable that the AAT also shares this same issue of overestimating the perfusion deficit. The degree to which extracranial and intracranial stenoses influence AAT is underinvestigated, and further studies are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. David Feinberg from Advanced MRI Technologies LLC, Claire Sexton for recruiting control participants, and Dr. Saad Jbabdi for useful discussions.

Abbreviations

- AAT

arterial arrival time

- ASL

arterial spin-labeling

- AUH

area under the histogram

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- DSC

dynamic susceptibility contrast

- DWI

diffusion-weighted imaging

- FMRIB

Functional MRI of the Brain

- GRASE

gradient and spin-echo

- ICA

internal carotid artery

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- PASL

pulsed arterial spin-labeling

- TIA

transient ischemic attack

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (B.J.M.), the Medical Research Council (P.J.), the Dunhill Medical Trust (P.J.), the Wellcome Trust (R.P.C.), the German Ministry of Education and Research (M.G.) and the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Programme.

References

- 1. Detre JA, Alsop DC, Vives LR, et al. Noninvasive MRI evaluation of cerebral blood flow in cerebrovascular disease. Neurology 1998;50:633–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chalela JA, Alsop DC, Gonzalez-Atavales JB, et al. Magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in acute ischemic stroke using continuous arterial spin labeling. Stroke 2000;31:680–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hendrikse J, van Osch MJ, Rutgers DR, et al. Internal carotid artery occlusion assessed at pulsed arterial spin-labeling perfusion MR imaging at multiple delay times. Radiology 2004;233:899–904. Epub 2004 Oct 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Laar PJ, Hendrikse J, Klijn CJ, et al. Symptomatic carotid artery occlusion: flow territories of major brain-feeding arteries. Radiology 2007;242:526–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bokkers RP, van Laar PJ, van de Ven KC, et al. Arterial spin-labeling MR imaging measurements of timing parameters in patients with a carotid artery occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1698–703. Epub 2008 Aug 13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim SG. Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional mapping. Magn Reson Med 1995;34:293–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Günther M, Oshio K, Feinberg DA. Single-shot 3D imaging techniques improve arterial spin labeling perfusion measurements. Magn Reson Med 2005;54:491–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buxton RB, Frank LR, Wong EC, et al. A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 1998;40:383–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacIntosh BJ, Pattinson KT, Gallichan D, et al. Measuring the effects of remifentanil on cerebral blood flow and arterial arrival time using 3D GRASE MRI with pulsed arterial spin labelling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008;28:1514–22. Epub 2008 May 28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. MacIntosh BJ, Filippini N, Chappell MA, et al. Assessment of arterial arrival times derived from multiple inversion time pulsed arterial spin labeling MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:641–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hendrikse J, Petersen ET, van Laar PJ, et al. Cerebral border zones between distal end branches of intracranial arteries: MR imaging. Radiology 2008;246:572–80. Epub 2007 Nov 30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiehler J, Foth M, Kucinski T, et al. Severe ADC decreases do not predict irreversible tissue damage in humans. Stroke 2002;33:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Restrepo L, Jacobs MA, Barker PB, et al. Assessment of transient ischemic attack with diffusion- and perfusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1645–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]