SUMMARY:

Stenosis of a DVA may result in chronic venous ischemia. We present 6 patients (3 men, 3 women; age range, 30–79 years; mean age, 53 years) with unilateral calcification of the caudate and putamen on noncontrast CT. This calcification typically spared the anterior limb of the internal capsule. No patient presented with symptoms referable to the basal ganglia or had an underlying metabolic disorder or other process associated with calcium deposition. All patients subsequently underwent gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging and/or CTA or conventional angiography demonstrating the presence of an adjacent DVA. We hypothesize that chronic venous ischemia in the drainage territory of the DVA causes the abnormal mineralization. Greater recognition of this entity will prevent misinterpretation of this finding as acute hemorrhage and will prevent unnecessary and sometimes invasive evaluation in such patients. Furthermore, this entity should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unilateral basal ganglia hyperattenuation.

DVA consists of a radial complex of medullary veins draining normal brain parenchyma and converging toward a common trunk that ultimately drains into the deep venous system (medullary veins, subependymal veins, and deep cerebral veins) or the superficial venous system (cortical veins and/or dural sinuses).1–3 Acute occlusion of a DVA due to thrombosis, surgical ligation, or resection may produce catastrophic venous ischemic and/or hemorrhagic complications.3–5

Initial reports of DVAs depicted by cerebral conventional angiography concluded that a DVA is a rare malformation with a propensity for complications, particularly hemorrhage.1,2,6–9 More recently, DVAs have been recognized as the most common vascular malformation of the brain, occurring in approximately 3% of all patients, and having an almost uniformly benign course. They are frequent incidental findings on contrast-enhanced CT and MR imaging examinations, as well as on postmortem examinations.2,5

The association of DVAs with cavernous malformations is well recognized, and cavernous malformations have been demonstrated to emerge with time in the vicinity of DVAs.3–5 Focal vascular narrowing within the common venous stem of a DVA has also been described, and this feature has been implicated in the development of localized venous hypertension in the brain territory drained by the DVA.3,5,8,10,11 This may lead to gliosis and encephalomalacia,5,9,12–14 as well as dystrophic parenchymal calcification in that territory.3,5,13 Venous stenosis can be difficult to demonstrate in DVAs, because they may be small and are seldom assessed with conventional angiography. Venous hypertension may also occur in the absence of frank stenosis, because venous wall thickening and hyalinization may create increased resistance, diminished compliance, and venous hypertension without frank stenosis.3,5,14 The relationship of venous hypertension to dystrophic parenchymal calcification is not unique to DVAs and is also described in Sturge-Weber syndrome and dural arteriovenous fistulas and, recently, as a manifestation of congenital atresia of venous sinuses.5,15–18

We present a series of 6 cases demonstrating unilateral caudate and putaminal mineralization in association with a DVA. To our knowledge, only a single example of this association on cross-sectional imaging has been presented previously in the literature.5 Consequently, this benign entity may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis of unilateral calcification of the caudate and putamen,19–24 potentially leading to misdiagnosis, unnecessary laboratory evaluations, or more invasive testing.

Materials and Methods

Case Series

Six patients (3 women and 3 men; age range, 30–79 years; mean age, 53 years) identified during routine clinical readout at the authors' institutions during the past decade exhibited unilateral isolated mineralization of the caudate and putamen on CT. All patients were found to have normal electrolyte values on routine analysis, and no patient had an underlying disorder associated with deposition of calcium or other minerals. Gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging and/or conventional angiography was subsequently performed in all cases, demonstrating the presence of an associated DVA in all patients. This group of patients constituted our study population.

These cases were then assessed, with approval from our institutional review board, for the following features on CT: side of involvement, extent of caudate and putaminal mineralization, presence of associated globus pallidus or anterior limb of internal capsule mineralization, and any acute ischemia or hemorrhage in proximity to or remote from the caudate and putaminal mineralization. On MR imaging (5 of 6 patients), we assessed the presence of mass effect or parenchymal T2 hyperintensity, the morphology of the DVA and its drainage pattern (deep versus superficial), the presence of definite stenosis of any branches or the common stem of the DVA, the presence of any additional DVAs, and the presence of any acute ischemia or hemorrhage in proximity to or remote from the involved basal ganglia. Patients undergoing CT angiography (3 patients) or conventional angiography (3 patients) were further evaluated for the presence of findings suggesting venous stenosis or occlusion (eg, focal vascular narrowing or localized persistence of venous contrast beyond other non-DVA associated veins in the region). Clinical characteristics and imaging results for our patients are summarized in the Table.

Clinical and imaging characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | Patient |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| General | ||||||

| Age (yr)/sex | 50/M | 39/M | 79/F | 70/F | 48/F | 30/M |

| Presentation | HA | HA | ICH | ICH | HA, SZ | HA |

| CT | ||||||

| Side | L | R | R | R | R | R |

| Ca2+ distributiona | C + P | C + Pb | C + Pb | C + P | C + P | C + P |

| CTA | NA | DVA, otherwise negative | NA | AVM, DVA; otherwise negative | Large DVA with venous restriction | NA |

| MR imaging | ||||||

| Mass effect | – | – | – | – | –c | – |

| T2 Change | – | – | – | – | NA | – |

| DVA drainage | Deep | Deep | Deep | Deep | Deep | Deep |

| Angiography | ||||||

| Venous restriction | NA | – | NA | – | + | NA |

| Additional features | Ipsilateral prominence of frontal horn | Ipsilateral prominence of frontal horn, | Ipsilateral prominence of frontal horn, | Ipsilateral prominence of frontal horn, | ||

| 2nd DVA, periphery right frontal lobe | Right frontal lobar ICH | Right frontal/parietal lobar ICH | ||||

Note:— –indicates negative.

Preferential calcification of the caudate and anterior putamen was noted in all cases, with at least partial sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule.

Trace high density of the globus pallidus interna was noted, characteristic of senescent mineralization, involving the globus pallidus interna on the left in case 2 and bilaterally in case 3.

MR imaging was not available; cross-sectional assessment was performed by CT and CTA.

The caudate and putaminal mineralization was incidentally discovered during the evaluation of unrelated clinical abnormalities in all patients. Presenting symptoms included headache in all patients; a single patient presented with seizures. Two patients presented in the setting of lobar hemorrhages remote from their DVAs, 1 of which was subsequently discovered by conventional angiography to be secondary to an arteriovenous malformation (Fig 1 ), and the other was presumed to be the consequence of severe thrombocytopenia in the setting of myelodysplastic syndrome.

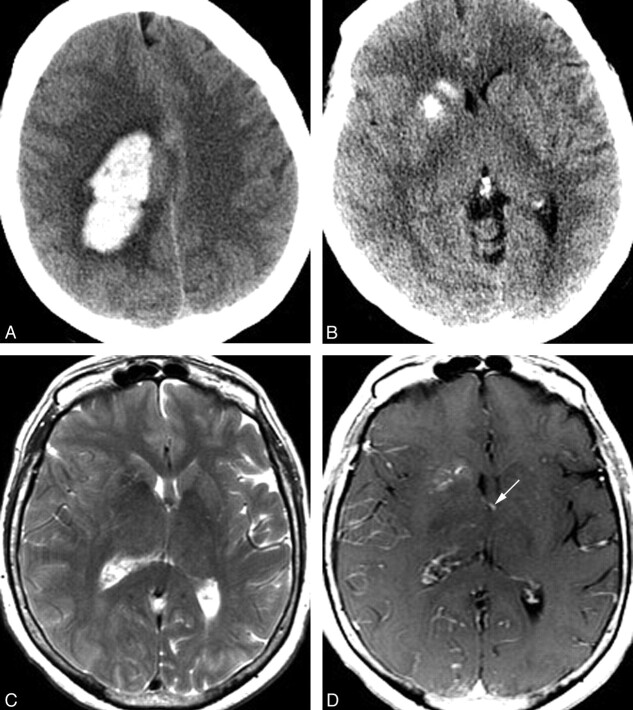

Fig 1.

A 70-year-old woman presenting with acute onset of headache and left-sided weakness. A, Noncontrast head CT scan demonstrates a large right frontoparietal lobar hemorrhage with surrounding vasogenic edema. This hemorrhage was subsequently shown to be due to a right hemispheric arteriovenous malformation with intranidal and flow-related aneurysms. B, CT scan caudal to A demonstrates calcification of the right caudate and anterior putamen, with sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule. C, Axial T2 MR image at a similar level demonstrates normal to slightly decreased signal intensity in the right caudate and putamen. Mild sulcal effacement in the right hemisphere is due to mass effect from the more superior parenchymal hematoma. Despite this, the right frontal horn is mildly dilated compared with the left. D, Axial T1 postgadolinium image demonstrates a DVA involving the right caudate and putamen. This DVA drains into an ependymal vein, likely the right thalamostriate vein, which is partly included on this image (arrow).

Findings were right-sided in 5 of 6 patients and left-sided in 1 patient. On CT, each patient had stippled dystrophic-appearing calcification of the basal ganglia involving the caudate and putamen unilaterally (Fig 2); preferential involvement of the anterior putamen was noted in all cases, with sparing of the posterior putamen. There was also relative sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule. One patient, a 79-year-old woman, demonstrated concomitant calcification of the globus pallidus interna bilaterally, characteristic of unrelated senescent changes. No associated mass effect was present in any case. In fact, there was mild prominence of the ipsilateral frontal horn of the lateral ventricle in 4 of 6 cases, consistent with mild parenchymal volume loss.

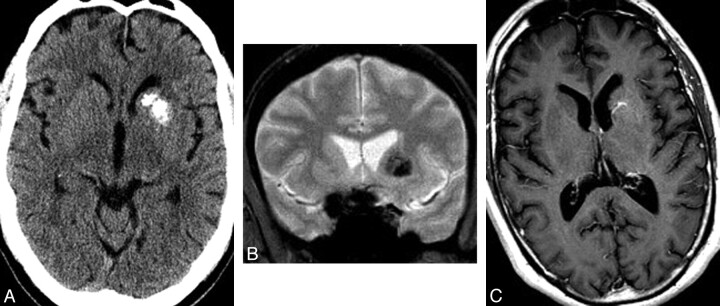

Fig 2.

A 50-year-old man presenting with headache. A, Noncontrast CT scan of the brain demonstrates calcification involving the left caudate and putamen without mass effect and with some encroachment on but relative sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule. Mild asymmetric prominence of the left frontal ventricular horn is consistent with mild volume loss. B, Coronal gradient recalled-echo image demonstrates signal-intensity loss due to susceptibility effects in the distribution of the basal ganglia mineralization. C, Axial T1 postgadolinium MR image demonstrates enhancing venous radicles in the left basal ganglia, converging on a common venous stem that courses toward the adjacent ventricular surface. Findings of T2- and diffusion-weighted images (not shown) were normal.

Gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging was performed in 5 patients, and all MR images demonstrated a typical DVA ipsilateral to the caudate and putaminal mineralization. No patient demonstrated any associated T2 hyperintensity in the corpus striatum or adjacent white matter. No patient demonstrated imaging evidence of a cavernous malformation in the region of the DVA or elsewhere in the brain or evidence of prior hemosiderin deposition. In all cases, the DVA drained to deep subependymal veins and subsequently to the deep venous system. There was no evidence of clear-cut focal venous stenosis in the draining DVA in any case on MR imaging; however, in all these cases, the radicles of the DVA were on the order of 1 mm and stenosis could not be conclusively determined. One patient had a second DVA in the right frontal lobe that was not associated with any parenchymal abnormality on CT or MR imaging. Two patients (patients 2 and 4) underwent CTA and DSA in addition to their MR imaging studies, and in neither case was stenosis of the DVA stem or radicles clearly demonstrated. One patient (patient 5) underwent only CTA and conventional angiography and no contrast-enhanced MR imaging. In this case of a very large DVA (Fig 3), mild venous stenosis was detected at the point where the anomalous draining vein joined the deep venous system.

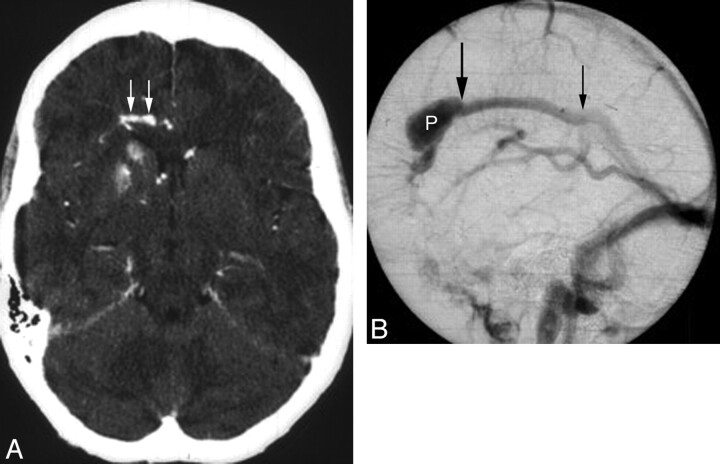

Fig 3.

A 48-year-old woman presenting with headache and seizure. A, An axial source image from CTA demonstrates mineralization of the right caudate and anterior putamen, with sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule. The patient's noncontrast head CT (not shown) also demonstrated this finding. An adjacent developmental venous anomaly (white arrows) is demonstrated in the periventricular white matter, coursing toward the midline. B, Lateral-projection venous phase image from a catheter angiogram demonstrates the venous radicles of the DVA converging toward a common venous pouch (P). A focal stenosis (large black arrow) manifested as a caliber transition zone is present where the pouch meets the inferior sagittal sinus; a second possible stenosis is present at the point where the inferior sagittal sinus drains to the Galenic system.

Discussion

Developmental venous anomalies represent the most common cerebral vascular malformation and generally have a benign course. Because these congenital variants of the medullary venous system drain normal brain parenchyma, they are generally considered “do not touch” lesions because potentially catastrophic consequences may follow their ligation or resection.

DVAs may be associated with other vascular malformations, notably cavernous malformations, capillary telangiectasias, and arteriovenous malformations; in addition, DVAs may be multiple in 2%–16% of cases.5,14,25–27 Cavernous malformations associated with DVAs likely represent the pathologic end point of repeated microhemorrhages secondary to stenosis or occlusion of small branches of the DVA, leading to vascular cavern proliferation and multiple endothelium-lined sinusoidal nonuniform vascular channels devoid of mature vessel wall elements and containing thrombosed blood of varying ages.3,5,14,27,28 The related complication and presumptive inciting pathophysiology of venous hypertension have also been directly angiographically documented in large DVAs, with demonstration of pressure gradients across the venous stenosis of the DVA.3 This pressure gradient may lead to changes within the tissues drained by the DVA as a consequence of chronic venous hypertension and presumably initiates a cascade of histopathologic changes leading to the development of dystrophic calcification and gliosis in such tissues.5,14

Given the frequent presence of DVAs in the vicinity of the frontal ventricular horns, the development of associated tissue changes in the caudate and putamen is not surprising.5,29 Our series suggests that this change is uncommon but not rare, presumably reflecting the fact that most DVAs are not complicated by the development of venous stenosis and hypertension. Corpus striatum calcification has been described in a variety of other disorders, notably metabolic conditions with altered calcium/phosphate balance, postinflammatory and postinfectious states, and following toxic or ischemic injury to the brain; these disorders, however, do not typically lead to unilateral involvement.19–24 The differential diagnosis of unilateral calcification of the corpus striatum is more limited and is generally related to prior unilateral injury such as infection or neoplasm (eg, treated toxoplasmosis, lymphoma, other granulomatous diseases, or human immunodeficiency virus infection itself).23,24 In the context of postinfectious calcification or calcification related to prior neoplasm, we would also expect the calcification to be more irregular and multifocal, rather than fine and stippled. Our series would suggest that DVA is likely not an uncommon etiology of this finding, and recognition of the benign course of this condition is important in differentiating it from other etiologies on clinical grounds.

In contrast to senescent basal ganglia calcification in the aging brain, which characteristically involves the globus pallidus, we observed a pattern of calcification primarily involving the caudate and anterior putamen, with relative sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule (Fig 4). The basis of this capsular sparing remains speculative but may reflect differential vulnerability of the deep gray matter versus white matter to chronic venous hypertension, or it may reflect some degree of variable anatomy of the deep medullary venous zones of convergence, as recently illustrated by Okudera et al.30 We expect that drainage of a DVA more posteriorly rather than toward the frontal horn could result in a pattern of unilateral posterior putaminal and thalamic mineralization, and the appearance of unilateral calcification of these structures on CT should also raise associated DVA as the likely underlying diagnosis. It is possible that this finding, though uncommon, may turn out to be more generalizable to other regions of the brain with poor venous collateral circulation.

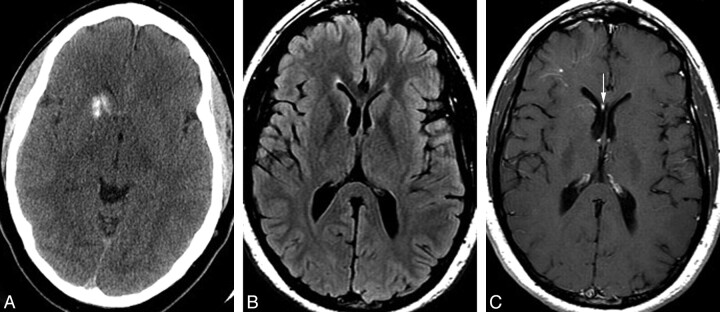

Fig 4.

A 39-year-old man with a history of antithrombin III deficiency, presenting with headache and suspicion for intracranial hemorrhage. Some years earlier, the patient had been told that he had a “right basal ganglia hemorrhage.” A, Noncontrast head CT demonstrates unilateral mineralization of the right caudate and anterior putamen, with relative sparing of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, which can be seen between the caudate and putaminal mineralization. B, Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR image shows no hyperintensity in the right caudate or putamen but rather a subtle hypointensity due to the calcification. The right frontal horn is mildly dilated, consistent with subtle volume loss in the right basal ganglia. C, Axial T1 postgadolinium image demonstrates a deep DVA involving the right basal ganglia and draining toward a right subependymal vein and then to the right septal vein (arrow). A second more superficial DVA is present in the subcortical right frontal region. Mild asymmetric prominence of the right frontal ventricular horn is again consistent with subtle parenchymal volume loss.

We hypothesize that chronic venous ischemia in the territory drained by a DVA causes parenchymal changes that may result in a potentially confusing pattern of unilateral caudate and putaminal calcification. Increased recognition of this entity as a primary diagnostic consideration is necessary to avoid unnecessary and potentially invasive examinations, as well as to alleviate concern among patients and referring physicians in such cases.

Conclusions

DVA is the most common cerebral vascular abnormality and generally follows a benign clinical course. In some cases, venous hypertensive changes in the territory drained by a DVA may lead to secondary venous ischemic changes, manifesting as unilateral calcification of the caudate and anterior putamen in cases of DVA near the frontal ventricular horns. We believe that a DVA with secondary venous ischemia is an under-recognized cause of unilateral calcification of the basal ganglia and that appreciation of this entity will help to avoid unnecessary and potentially invasive evaluation in most of these patients.

Abbreviations

- AVM

arteriovenous malformation

- C

caudate

- Ca2+

calcification

- CTA

CT angiography

- DVA

developmental venous anomaly

- HA

headache

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- L

left

- NA

not applicable

- P

putamen

- R

right

- SZ

seizure

References

- 1. Sarwar M, Mccormick WF. Intracerebral venous angioma. Arch Neurol 1978;35:323–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garner TB, Curling OD, Kelly DL, et al. The natural history of intracranial venous angiomas. J Neurosurg 1991;75:715–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dillon WP. Cryptic vascular malformations: controversies in terminology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997;18:1839–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rigamonti D, Spetzler R. The association of venous and cavernous malformations: report of four cases and discussion of the pathophysiological, diagnostic, and therapeutic implications. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1988; 92:100–05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. San Millan Ruiz D, Delavelle J, Yilmaz H, et al. Parenchymal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. Neuroradiology 2007;49:987–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Margolis G, Odom GL, Woodhall B, et al. The role of small angiomatous malformations in the production of intracerebral hematomas. J Neurosurg 1951;8:564–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crawford J, Russell D. Cryptic arteriovenous and venous hamartomas of the brain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1956;19:1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Truwit CL. Venous angioma of the brain: history, significance, and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:1299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saito Y, Kobayashi N. Cerebral venous angiomas. Radiology 1981;139:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moody DM, Brown WR, Challa VR, et al. Periventricular venous collagenosis: association with leukoaraiosis. Radiology 1995;194:469–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Munoz DG, Hastak SM, Harper B, et al. Pathologic correlates of increased signals of the centrum ovale on magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol 1993;50:492–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uchino A, Sawada A, Takase Y. Cerebral hemiatrophy caused by multiple developmental venous anomalies involving nearly the entire cerebral hemisphere. Clin Imaging 2001;25:82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCormick W. The pathology of vascular “arteriovenous” malformations. J Neurosurg 1966;24:807–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. San Millan Ruiz D, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies: current concepts. Ann Neurol 2009;66:271–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huber G, Henkes H, Hermes M. Regional association of developmental venous anomalies with angiographically occult vascular malformations. Eur Radiol 1996;6:30–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen Z, Fenga H, Zhua G, et al. Anomalous intracranial venous drainage associated with basal ganglia calcification. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:22–24 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang MS, Chen CC, Cheng YY, et al. Unilateral subcortical calcification: a manifestation of dural arteriovenous fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1149–51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu YL, Chiu EK, Woo E. Dystrophic intracranial calcification: CT evidence of “cerebral steal” from arteriovenous malformation. Neuroradiology 1987;29:519–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen CR, Duchesneau PM, Weinstein MA. Calcification of the basal ganglia as visualized by computed tomography. Radiology 1980;134:97–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ilium F. Calcification of the basal ganglia following carbon monoxide poisoning. Neuroradiology 1980;19:213–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gastaut H, Gastaut JL, Régis H, et al. Computerized tomography in the study of West's syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 1978;20:21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vermersch P, Leys D, Pruvo JP, et al. Parkinson's disease and basal ganglia calcifications: prevalence and clinico-radiological correlations. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1992;94:213–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Epstein LG, Berman CZ, Sharer LR, et al. Unilateral calcification and contrast enhancement of the basal ganglia in a child with AIDS encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1987;8:163–65 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salzman KL. Basal ganglia calcification. In: Osborn AG, Ross JS, Crim J, et al., eds. Expert ddx: Brain and Spine. Salt Lake City: Amirsys; 2008:62 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rigamonti D, Johnson PC, Spetzler RF, et al. Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery 1991;28:60–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCormick PW, Spetzler RF, Johnson PC, et al. Cerebellar hemorrhage associated with capillary telangiectasia and venous angioma: a case report. Surg Neurol 1993;39:451–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abe T, Singer RJ, Marks MP, et al. Coexistence of occult vascular malformations and developmental venous anomalies in the central nervous system: MR evaluation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998;19:51–57 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tomlinson FH, Houser OW, Scheithauer BW, et al. Angiographically occult vascular malformations: a correlative study of features on magnetic resonance imaging and histological examination. Neurosurgery 1994;34:792–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee C, Pennington MA, Kenney CM. MR evaluation of developmental venous anomalies: medullary venous anatomy of venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:61–70 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Okudera T, Huang YP, Fukusumi A, et al. Micro-angiographical studies of the medullary venous system of the cerebral hemisphere. Neuropathology 1999;19:93–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]