Abstract

The grand challenge of protein design is a general method for producing a polypeptide with arbitrary functionality, conformation, and biochemical properties. To that end, a wide variety of methods have been developed for the improvement of native proteins, the design of ideal proteins de novo, and the redesign of suboptimal proteins with better-performing substructures. These methods employ informatic comparisons of function-structure-sequence relationships as well as knowledge-based evaluation of protein properties to narrow the immense protein sequence search space down to an enumerable and often manually evaluable set of structures that meet specified criteria. While arbitrary manipulation of protein-protein interfaces and molecular catalysis remains an unsolved problem, and no protein shape or behavior manipulation algorithm is universally applicable, the promising results thus far are a strong indicator that a general approach to the arbitrary manipulation of polypeptides is within reach.

Keywords: Rosetta, protein design, de novo design, Protein Engineering, molecular modeling, simulation, protein structure

Introduction

Computational protein design is a subset of the larger protein engineering field. Rather than rely on human intuition and/or directed evolution as has been done traditionally, computational protein design entails the modification and evaluation of an in silico protein model. The advantage of computational simulation is that it enables rapid testing and iteration of design tasks prior to slow and expensive laboratory experiments. However, simulations are limited by how reliably a model recapitulates the solution state of a protein. In recent years, this scientific discipline has started to undergo a renaissance, where the methodology is rapidly becoming more accurate and capable. This review will focus primarily on structure-based protein design methodology, which can be divided into three broadly overlapping categories based on objective: design of protein shape, function, and solution behavior. These capabilities can also be considered dynamically; control of protein shape and behavior is equivalent to attenuating undesired dynamics, while protein function can be modeled as the promotion of desired dynamics. At the intersection of these three capabilities lies the “holy grail” of protein engineering: complete, rational control over protein structure and function; the ability to create a protein to perform any task.

Design of protein shape

The explicit design of protein shape and tertiary structure given an environment is an important design consideration in order to attain higher-order structure and complex function, and it requires precise control of component oligomerization, orientation, and folding. The development of new computational tools to aid in this task has had a profound impact on our ability to design useful protein topologies and oligomeric architectures.

In order to design new topologies, many methods have been proposed and used to generate novel protein folds or folds around known functional motifs. One of the first such tools was RosettaRemodel [9], which was instrumental in giving designers a means to control protein shape that is sampled through short protein fragment assembly and controlled through a specialized blueprint file for de novo design, domain insertion, circular permutation, and extension/deletion. For de novo design, however, this method requires per-residue level consideration of secondary structure, making it difficult to explicitly control overall topologies a priori. Even with this limitation, designers have been able to overcome this through active scripting, geometrical constraints, and structural filters to design and experimentally characterize a variety of de novo topologies [10-13].

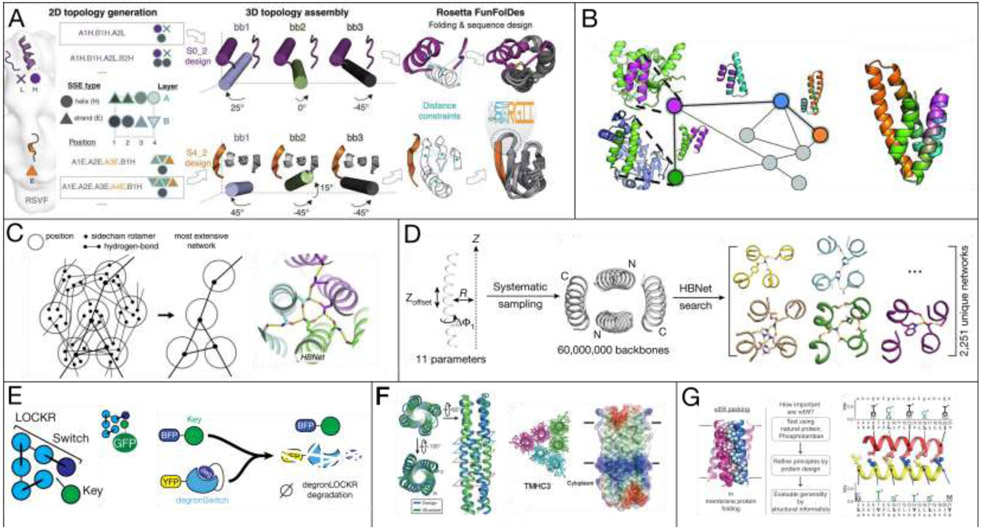

Similarly, TopoBuilder allows a designer full control over protein secondary structure topology and 3-dimensional secondary structure orientation; supporting a unique graphical user interface to define complex protein topologies in 3-D space. This methodology, which is built around the FunFoldDes protocol [14], was successfully used in the design of a cocktail of novel immunogens for RSV. These immunogens adopt unique protein folds and incorporate custom motifs of interest to enable strong binding to RSV-targeting antibodies (Figure 2A) [1]. Fold topology was confirmed to match the design models by x-ray crystallography, strong binding affinity was confirmed through an RSV nAb panel using SPR, and the cocktail was confirmed to elicit a neutralizing antibody response in-vivo to RSV in mice and non-human primates.

Figure 2.

(A) Topobuilder allows a designer full topological control of protein shape, in this case with motif building for RSV immunogens [1]. (B) SEWING builds protein shape by chimerizing larger protein substructures [2]. (C) HBNet searches probable low-energy hydrogen bonding arrangements through sidechain rotamers and graphs [3,4]. (D) Orthogonal Heterdimer design using parametric backbone sampling and HBNet [5,6]. (E) LOCKR switch design where a protein key binds more favorably than the switch oligomer, enabling design of function, such as degradation [5-7]. (F) Transmembrane protein design of different complexities using Parametric design and HBNet [5]. (G) The elucidation of first-principles of membrane protein design through modeling and design of transmembrane proteins [8].

A different approach to protein shape design is to employ large pieces of known protein segments, which are controlled by the designer, and ‘sew’ them together to attain new protein geometries and surfaces not seen in nature, but guided by known structural motifs and global energetics (Figure 2B) [2]. This process is repeated hundreds of thousands of times to generate a multitude of potential protein backbones for which sequences can be designed onto, with optional support for design requirements like motifs or metal binding sites [15]. In this approach, control over protein structure comes from requirements, post-design filtering, and the careful selection of protein segments, rather than precise, rational enumeration of the protein structure by a human designer.

Finally, a more general tool, HBnet, [3,4], allows fine control over local and tertiary interactions through the explicit design of hydrogen bond networks on a provided protein backbone (Figure 2C). This methodology has already had an impact on our ability to carefully design protein shape, having been used in conjunction with parametric helical bundle design [16], in the recent design of transmembrane proteins [5], orthogonal heterodimers (Figure 2D) ([5,6], and protein switch design (Figure 2E) ([5-7].

Design of protein function

There are two overarching strategies which have been used to design proteins to perform novel functions: assembly of domains, and incorporation of function into a single domain. The former approach has been successfully employed in the past without the aid of computational tools [19], but recent advances in computational design are enabling protein domains to be assembled with increasing sophistication and precision. Most domain assemblies are designed with the goal of exerting spatio-temporal control over protein function. In its simplest form, designing a control mechanism involves positioning controllable domains with flexible linkers such that the function of interest can be sterically occluded. This approach has been successfully used to design light-controlled versions of structurally diverse proteins for use in optogenetic studies by constraining light-sensitive protein complexes over the active site of a functional protein (Figure 3A) [20,21].Light-induced oligomerization is another successful strategy for optogenetic control (Figure 3B) [22]. Boolean logic gates can also be constructed, either through the reversible sequestration of bioactive peptides in cages sensitive to the binding of inducible “key” proteins [23] or by establishing high-level control over the interactions of switch domains such that only specific switch conditions allow other switches to function [24]. These approaches are primarily limited by the structural requirements they impose on the functional domain: if the termini are occluded or positioned such that the control domains would clash with the functional domain, no control is possible.

Figure 3.

(A) Control over protein function may be established by sterically hindering the binding of other proteins [19]. (B) Alternatively, the protein of interest may be sequestered to a specific cellular location [21]. (C) The Spytag-Spycatcher system is one option for achieving this sequestration [24]. (D) Allosteric control of protein activity can expand the range of controllable proteins beyond those with free termini [25]. (E) Novel functions can be added through the insertion of functional motifs [26]. (F,G) Extant functional motifs can also be wrapped in new protein structures to stabilize them [15,27].

A protein’s function is dependent on structural conformation. Historically, efforts to confer novel function to proteins found in nature has had limited success. Few protein structures are suitable for a given function, and mutations which confer a novel function will quite frequently destabilize the structure. Armed with the ability to craft protein structures de novo, the field has been undergoing a shift away from using natural proteins as starting points for engineering function.

Motif insertion allows a closer approximation of de novo design of novel function; it is functionally close to grafting, but the protein scaffold is built around the functional region of interest, allowing for the stabilization of a wider range of motifs. This can be used to insert labels into structurally significant regions of the protein(Figure 3C) [25], to enable allosteric control by inserting conformationally variable domains into mobile regions of the protein(Figure 3D)[26], or to sample different loops with which to adjust protein surfaces(Figure 3E) [27]. Conversely, if the desired functionality can be localized to a small region of the protein, as with metal-binding proteins, an entirely new scaffold can be constructed around this region of interest(Figure 3F-G) [1,15,28,29]. These methods all suffer from the same fundamental limitation: insofar as a protein is only as stable as its least stable region and functional motifs have evolved under structural pressures aside from stability, the very functional regions that must be preserved by this method can also be among the most structurally compromising.

The design of wholly novel enzymes remains among the most significant and long-standing challenges in de novo protein design [30], owing in part to the structurally delocalized nature of many enzyme active sites and because we have an incomplete understanding of macromolecular catalysis in general. Advances in molecular computation and language-based modeling [31] have placed de novo enzyme design within closer reach by combining adversarial models of protein distance networks with conditional language models to produce functionally relevant sequences and assign them conformationally favorable structures. The design of protein dynamics has also been placed within closer reach by recent advancements in the determination of the structural underpinnings of conformational exchange, paving the way for the design of enzymatic dynamics into arbitrary proteins [32]. However, a general solution to the design of proteins with novel chemical characteristics will require a general solution to protein interface design, most likely through the use of structurally informed AI modeling of protein interfaces. No such solution presently exists, although recent advances in multi-scale structural classification show promise in generating trainable data sets. [33]

Design of protein behavior

In addition to performing a specific function, a successful protein therapeutic (e.g. an antibody) or tool (e.g. industrial catalyst) must also possess a suite of optimal solution behaviors. As such, substantial efforts have focused on elucidating and computationally designing solution behaviors such as thermostability, solubility, and viscosity. The goal of such efforts is to improve a protein’s solution properties while preserving its functionality. To date, efforts to predict and improve protein properties have focused on residue-level redesign, as adjustments to the protein mainchain involve a larger search space and are more likely to impact function.

While many general trends are known, a precise understanding of the sequence-structure relationship that determines protein thermostability remains elusive. Thus, the most successful methods today for improving protein thermostability leverage multiple sequence alignments to reduce the amino acid search space (Figure 4A) [34]. These methods work by creating a position-specific substitution matrix (PSSM) to screen out amino acids never seen at particular positions, followed by Rosetta-driven selection of energetically optimal mutations from among those amino acids allowed by the PSSM. As a final step, individually stabilizing mutations are examined combinatorially and those combinations ranked by ΔΔGcalc to produce a list of candidate mutation sets. This approach can theoretically solve systemic problems with a given structure, but is limited in scope by the variability of the underlying PSSM, leaving more radical changes and concomitantly dramatic improvements out of scope.

Figure 4.

(A)Protein stability may be improved by mutating away structurally improbable amino acids [32]. (B) Solubility is amenable to either force field-based improvements to the protein surface[36]. (C) Solubility may also be improved through the statistical detection of hydrophobic surface residues [38]. (D) Informatically driven identification of structurally suboptimal regions can compensate for inadequacies in physical models [34]. (E) Metrics of local structural frustration can also detect structural problems that residue-level approaches might miss [4]. (F) Ranking protein regions by the disorder predicted by their sequence can also identify problem regions amenable to stabilizing mutations [33]. (G) When all else fails, functionally interesting regions can be inserted into more stable scaffolds [35].

A fundamental challenge of predicting and designing protein solution behavior may be due to the fact that the majority of protein structures have been determined by X-ray crystallography, and thus are not for a protein in solution; generally, dynamics information, which are critical determinants of solution behavior, must be predicted or inferred. As such, many approaches leverage informatics in an effort to minimize reliance on the atomic coordinates of a protein structure. One such method predicts regions of a protein likely to be disordered and suggests stabilizing mutations (Figure 4F) [35]. This “worst spot” analysis works independently of which disorder-detecting algorithm is employed, and it has been used with several variations of PONDR (Predictor of Natural Disordered Regions) simultaneously in order to compensate for inaccuracies in any one approach. The consensus disorder rating is then used to inform targeted disulfide bond insertion, on the theory that proteins are only as stable as their least stable region. This is a versatile approach to detecting stabilizing mutations that theoretically does not need a structure as input, but it can only detect local disorder; if two subsets of the protein are each individually stable but incompatible with each other, this algorithm will not detect that. Structural metrics of local frustration (Figure 4E) [5] offer a complementary approach by considering mutually exclusive local fold optima explicitly in an attempt to identify regions which cannot concurrently fold, and it may be used to identify distributed structural suboptimality.

A wholly informatically driven approach has also been developed which performs favorably in cases where standard physical models are insufficient (Figure 4D) [36]. This compensates for inaccuracies in physical modeling by detecting geometric commonalities in stable native proteins, and suggesting mutations to residues more commonly found in each position’s local structural context. Here, only one- and two-body terms are considered; higher-order terms may capture more complete information about protein stability but are presently computationally intractable. This method excels at sequence recovery and other benchmarks commonly used for evaluating protein design force fields, but it assumes that the currently available protein structures completely represent protein sequence space; they are of limited utility where there is no structure that is both substantially similar to and more stable than the protein of interest.

In cases where a particular protein is not amenable to residue-level structural improvement, the functional region of interest may be grafted en bloc onto another, more stable protein by inserting those functional residues into a region of the second protein known to tolerate mutation. This approach has been successfully used to display epitopes for antibody development (Figure 4G) [37], but is limited by requiring the functionality of interest to be localized to a known region of the protein.

The methods described above primarily focus on improving thermostability, and while solution behaviors tend to correlate, there are methods which specifically address solubility. The simplest effective approach simply performs an automatic detection of hydrophobic surface residues, and designs minimally-perturbative polar residue substitutions at these positions (Figure 4B) [38]. Statistical methods have also been developed to determine protein solubility [39] and general developability (Figure 4C) [40] through evaluation of the geometric properties of the structure. In the first case, a series of proteins of known structure and solubility were used to train knowledge-based statistical potentials which can predict protein solubility based on interresidue interactions. In this way, solubility-increasing and aggregation-potentiating residue pairs were identified. In the second approach, structural determinants of antibody developability were extracted from comparisons between antibody therapeutics and other antibodies of known sequence. From this, parameters for optimal charge distribution were developed which can predict the developability of antibodies. While powerful, these methods rely on sequence similarity to inform their predictions, and are therefore limited to native-like proteins. The ability to predict and control the thermostability and solubility for any given protein remains an unsolved challenge. With the increasing amounts of data that are available for protein structure and solution behavior, it seems likely that machine learning approaches will factor heavily in future successes in this field, particularly in order to efficiently sample across conformational states in order to control dynamics

Future perspectives

Advancements in computational protein design infrastructure, such as sampling algorithms and energy functions, were not discussed here [41-43]. However, it is clear that future capabilities will be fueled by such advancements. Additionally, the ability to overcome biological challenges such as protein immunogenicity and blood-brain barrier permeability remain a critically important frontier. Solutions will require a deeper understanding of biology, and computational protein design can provide the investigative tools needed to both understand and control such complex behaviors. De novo enzyme design, perhaps the most challenging problem in protein design, will almost certainly require explicit sampling of multiple protein conformational states in order to achieve the high catalytic rates common to natural enzymes. Finally, machine learning techniques have rapidly improved the fidelity of protein structure prediction [44], and it is clear that machine learning will also drive concomitant advances in protein design in the coming years.

Figure 1.

Total control over proteins, including protein dynamics, requires that their shape, function, and general biochemical properties all be individually manipulable.

Footnotes

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- **1.Sesterhenn F, Yang C, Bonet J, Cramer JT, Wen X, Wang Y, Chiang C-I, Abriata LA, Kucharska I, Castoro G, et al. : De novo protein design enables the precise induction of RSV-neutralizing antibodies. Science 2020, 368.This paper describes a new method for designing de novo proteins from user-provided 2D topology, allowing a higher level of control in protein design. Notably, the method was rigorously tested on 3 different RSV motifs and shown to elicit a robust, focused antibody response in mice and non-human primates.

- 2.Jacobs TM, Williams B, Williams T, Xu X, Eletsky A, Federizon JF, Szyperski T, Kuhlman B: Design of structurally distinct proteins using strategies inspired by evolution. Science 2016, 352:687–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **3.Maguire JB, Boyken SE, Baker D, Kuhlman B: Rapid Sampling of Hydrogen Bond Networks for Computational Protein Design. J Chem Theory Comput 2018, 14:2751–2760.This work describes a reimagining of the original HBNet protocol which makes it fast enough to combine with other routine design protocols and tasks. This version of HBNet has had a rather large impact on the field and many papers in this review have employed this method to great effect.

- 4.Boyken SE, Chen Z, Groves B, Langan RA, Oberdorfer G, Ford A, Gilmore JM, Xu C, DiMaio F, Pereira JH, et al. : De novo design of protein homo-oligomers with modular hydrogen-bond network-mediated specificity. Science 2016, 352:680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu P, Min D, DiMaio F, Wei KY, Vahey MD, Boyken SE, Chen Z, Fallas JA, Ueda G, Sheffler W, et al. : Accurate computational design of multipass transmembrane proteins. Science 2018, 359:1042–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Boyken SE, Jia M, Busch F, Flores-Solis D, Bick MJ, Lu P, VanAernum ZL, Sahasrabuddhe A, Langan RA, et al. : Programmable design of orthogonal protein heterodimers. Nature 2018, 565:106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *7.Langan RA, Boyken SE, Ng AH, Samson JA, Dods G, Westbrook AM, Nguyen TH, Lajoie MJ, Chen Z, Berger S, et al. : De novo design of bioactive protein switches. Nature 2019, 572:205–210.This paper employed many protein design methods including HBNet to achieve a robust protein switch system, which has clear therapeutic potential. The utility of the LOCKR system was shown by incorporating three unique functional motifs and successfully testing them in vitro.

- 8.Mravic M, Thomaston JL, Tucker M, Solomon PE, Liu L, DeGrado WF: Packing of apolar side chains enables accurate design of highly stable membrane proteins. Science 2019, 363:1418–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang P-S, Ban Y-EA, Richter F, Andre I, Vernon R, Schief WR, Baker D: RosettaRemodel: a generalized framework for flexible backbone protein design. PLoS One 2011, 6:e24109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhardwaj G, Mulligan VK, Bahl CD, Gilmore JM, Harvey PJ, Cheneval O, Buchko GW, Pulavarti SVSRK, Kaas Q, Eletsky A, et al. : Accurate de novo design of hyperstable constrained peptides. Nature 2016, 538:329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chevalier A, Silva D-A, Rocklin GJ, Hicks DR, Vergara R, Murapa P, Bernard SM, Zhang L, Lam K-H, Yao G, et al. : Massively parallel de novo protein design for targeted therapeutics. Nature 2017, 550:74–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koga N, Tatsumi-Koga R, Liu G, Xiao R, Acton TB, Montelione GT, Baker D: Principles for designing ideal protein structures. Nature 2012, 491:222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchko GW, Pulavarti SVSRK, Ovchinnikov V, Shaw EA, Rettie SA, Myler PJ, Karplus M, Szyperski T, Baker D, Bahl CD: Cytosolic expression, solution structures, and molecular dynamics simulation of genetically encodable disulfide-rich de novo designed peptides. Protein Sci 2018, 27:1611–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonet J, Wehrle S, Schriever K, Yang C, Billet A, Sesterhenn F, Scheck A, Sverrisson F, Veselkova B, Vollers S, et al. : Rosetta FunFolDes – A general framework for the computational design of functional proteins. PLOS Computational Biology 2018, 14:e1006623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15.Guffy SL, Teets FD, Langlois MI, Kuhlman B: Protocols for Requirement-Driven Protein Design in the Rosetta Modeling Program. J Chem Inf Model 2018, 58:895–901.This paper describes a series of improvements to the SEWING algorithm to better incorporate extant binding sites and coordinate ligand binding, forming a robust algorithm for stable protein design.

- 16.Grigoryan G, DeGrado WF: Probing Designability via a Generalized Model of Helical Bundle Geometry. Journal of Molecular Biology 2011, 405:1079–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alford RF, Koehler Leman J, Weitzner BD, Duran AM, Tilley DC, Elazar A, Gray JJ: An Integrated Framework Advancing Membrane Protein Modeling and Design. PLoS Comput Biol 2015, 11:e1004398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alford RF, Fleming PJ, Fleming KG, Gray JJ: Protein Structure Prediction and Design in a Biologically Realistic Implicit Membrane. Biophysical Journal 2020, 118:2042–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arai R, Ueda H, Kitayama A, Kamiya N, Nagamune T: Design of the linkers which effectively separate domains of a bifunctional fusion protein. Protein Eng 2001, 14:529–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teets FD, Watanabe T, Hahn KM, Kuhlman B: A Computational Protocol for Regulating Protein Binding Reactions with a Light-Sensitive Protein Dimer. J Mol Biol 2020, 432:805–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.pubmeddev, Stone OJ et al. : Optogenetic control of cofilin and αTAT in living cells using Z-lock. - PubMed - NCBI. [date unknown], [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benedetti L, Barentine AES, Messa M, Wheeler H, Bewersdorf J, De Camilli P: Light-activated protein interaction with high spatial subcellular confinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115: E2238–E2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng AH, Nguyen TH, Gómez-Schiavon M, Dods G, Langan RA, Boyken SE, Samson JA, Waldburger LM, Dueber JE, Baker D, et al. : Publisher Correction: Modular and tunable biological feedback control using a de novo protein switch. Nature 2020, 579:E8–E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agrawal DK, Dolan EM, Hernandez NE, Blacklock KM, Khare SD, Sontag ED: Mathematical Models of Protease-Based Enzymatic Biosensors. ACS Synth Biol 2020, 9:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Hatlem D, Trunk T, Linke D, Leo JC: Catching a SPY: Using the SpyCatcher-SpyTag and Related Systems for Labeling and Localizing Bacterial Proteins. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20.This paper describes a novel use of the Spytag-Spycatcher system for sensing protein conformation by embedding the Spytag peptide in a flexible part of the protein, which extends this already versatile system to allow for biosensors of protein activity.

- 26.Dagliyan O, Dokholyan NV, Hahn KM: Engineering proteins for allosteric control by light or ligands. Nat Protoc 2019, 14:1863–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero MLR, Yang F, Lin Y-R, Toth-Petroczy A, Berezovsky IN, Goncearenco A, Yang W, Wellner A, Kumar-Deshmukh F, Sharon M, et al. : Simple yet functional phosphate-loop proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:E11943–E11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardi A, Pirro F, Maglio O, Chino M, DeGrado WF: De Novo Design of Four-Helix Bundle Metalloproteins: One Scaffold, Diverse Reactivities. Acc Chem Res 2019, 52:1148–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S-Q, Chino M, Liu L, Tang Y, Hu X, DeGrado WF, Lombardi A: De Novo Design of Tetranuclear Transition Metal Clusters Stabilized by Hydrogen-Bonded Networks in Helical Bundles. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140:1294–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Privett HK, Kiss G, Lee TM, Blomberg R, Chica RA, Thomas LM, Hilvert D, Houk KN, Mayo SL: Iterative approach to computational enzyme design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109:3790–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madani A, McCann B, Naik N, Keskar NS, Anand N, Eguchi RR, Huang P-S, Socher R: ProGen: Language Modeling for Protein Generation. bioRxiv 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.03.07.982272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damry AM, Mayer MM, Broom A, Goto NK, Chica RA: Origin of conformational dynamics in a globular protein. Communications Biology 2019, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo F, Zou Q, Yang G, Wang D, Tang J, Xu J: Identifying protein-protein interface via a novel multi-scale local sequence and structural representation. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldenzweig A, Goldsmith M, Hill SE, Gertman O, Laurino P, Ashani Y, Dym O, Unger T, Albeck S, Prilusky J, et al. : Automated Structure- and Sequence-Based Design of Proteins for High Bacterial Expression and Stability. Mol Cell 2018, 70:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagibina GS, Glukhova KA, Uversky VN, Melnik TN, Melnik BS: Intrinsic Disorder-Based Design of Stable Globular Proteins. Biomolecules 2019, 10:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou J, Panaitiu AE, Grigoryan G: A general-purpose protein design framework based on mining sequence–structure relationships in known protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117:1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peeß C, Scholz C, Casagolda D, Düfel H, Gerg M, Kowalewsky F, Bocola M, von Proff L, Goller S, Klöppel-Swarlik H, et al. : A novel epitope-presenting thermostable scaffold for the development of highly specific insulin-like growth factor-1/2 antibodies. J Biol Chem 2019, 294:13434–13444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Lau Y-TK, Baytshtok V, Howard TA, Fiala BM, Johnson JM, Carter LP, Baker D, Lima CD, Bahl CD: Discovery and engineering of enhanced SUMO protease enzymes. J Biol Chem 2018, 293:13224–13233.This paper not only describes a novel SUMO protease with improved stability over wild type but also includes a general approach to making solubility-enhancing surface mutations while preserving enzymatic activity.

- 39.Hou Q, Bourgeas R, Pucci F, Rooman M: Computational analysis of the amino acid interactions that promote or decrease protein solubility. Sci Rep 2018, 8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raybould MIJ, Marks C, Krawczyk K, Taddese B, Nowak J, Lewis AP, Bujotzek A, Shi J, Deane CM: Five computational developability guidelines for therapeutic antibody profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:4025–4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alford RF, Leaver-Fay A, Jeliazkov JR, O’Meara MJ, DiMaio FP, Park H, Shapovalov MV, Renfrew PD, Mulligan VK, Kappel K, et al. : The Rosetta All-Atom Energy Function for Macromolecular Modeling and Design. J Chem Theory Comput 2017, 13:3031–3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leman JK, Weitzner BD, Lewis SM, Adolf-Bryfogle J, Alam N, Alford RF, Aprahamian M, Baker D, Barlow KA, Barth P, et al. : Macromolecular modeling and design in Rosetta: recent methods and frameworks. Nat Methods 2020, 17:665–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ford AS, Weitzner BD, Bahl CD: Integration of the Rosetta suite with the python software stack via reproducible packaging and core programming interfaces for distributed simulation. Protein Sci 2020, 29:43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senior AW, Evans R, Jumper J, Kirkpatrick J, Sifre L, Green T, Qin C, Žídek A, Nelson AWR, Bridgland A, et al. : Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature 2020, 577:706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]