Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a clinical deterioration that occurs despite increasing CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and decreasing plasma human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) viral loads. It results from an inflammatory response or “dysregulation” of the immune system to both intact subclinical pathogens and residual antigens. Resulting clinical manifestations of this syndrome are diverse and depend on the infectious or noninfectious agent involved.1 Neurologic symptoms and signs of IRIS have been reported in association with clinical and subclinical infections, such as cryptococcosis, tuberculosis, mycobacteriosis, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,2 as well as noninfectious phenomena. There are very rare reports of neurologic IRIS associated with cerebral toxoplasmosis.3,4

A 26-year-old woman with HIV-1 infection for 8 years presented with a 1-month history of ataxia, left-sided weakness, and hyperreflexia. She was not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regularly and was referred to treatment for cerebral toxoplasmosis 4 years before with clinical and radiologic improvement. Currently, a CT scan showed scattered calcified lesions in the brain parenchyma with no perilesional edema or contrast enhancement. On clinical examination, her mental status was normal, and no papilledema was present. Relevant laboratory tests were a positive HIV-1 test result, a CD4 cell count of 276 × 109 cells/L, and a plasma HIV-1 ribonucleic acid (RNA) load of 105.452 copies/mL. CSF evaluation revealed the following values: 3 cells/mL; protein, 32 mg/dL; glucose, 44 mg/dL; sterile cultures; and negative polymerase chain reaction for JC virus (JCV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), Toxoplasma gondii, and Epstein-Barr virus. Brain MR imaging showed multiple areas of high signal intensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, some presenting nodular or ring enhancement, located mainly in the subcortical white matter and deep gray matter (Fig 1A, -B). The larger lesion, seen in the left frontal lobe, had marked low signal intensity on the T2*-weighted images, suggesting calcification, corroborating the CT findings. Treatment was initiated with sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and folinic acid. HAART was restored with tenofovir, lamivudine, lopinavir, and ritonavir. She was treated for 3 weeks without clinical or radiologic improvement.

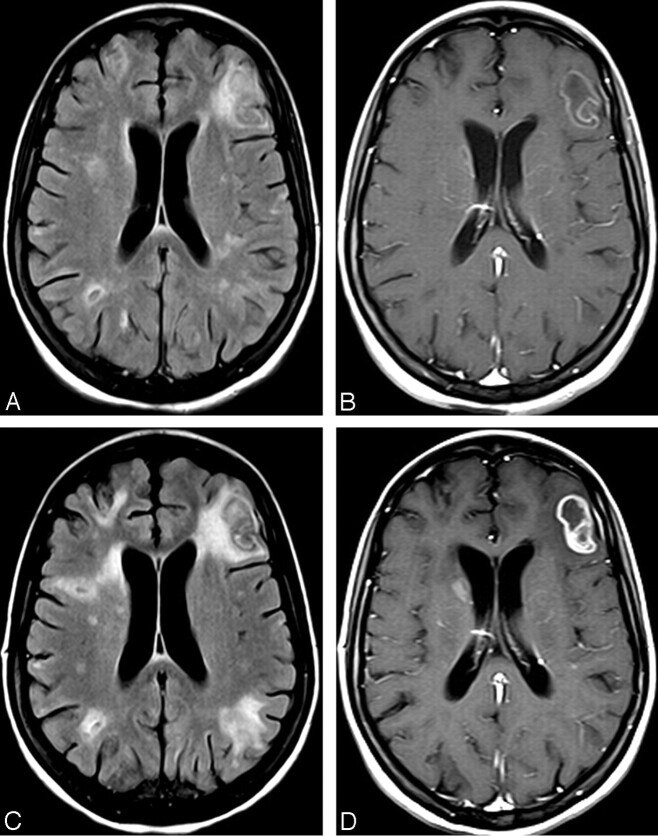

Fig 1.

A, FLAIR image at admission shows multiple areas of high signal intensity, some with a central area of low signal intensity, located in the subcortical and periventricular white matter. B, T1-weighted image after gadolinium administration demonstrates mild ring enhancement in the left frontal lesion, as well as in the lesion in the head of the right caudate nucleus. C, FLAIR image 1 month later shows significant increase in the size of the areas of high signal intensity in the white matter. D, T1-weighted image after gadolinium administration demonstrates stronger enhancement in the lesions at the left frontal lobe and right caudate nucleus, as well as new nodular areas of enhancement bilaterally.

One month after the beginning of treatment for cerebral toxoplasmosis, she presented with worsening of clinical signs and symptoms. A new brain MR imaging revealed enlargement of most of the lesions, mainly with perilesional high signal intensity on FLAIR images, as well as stronger contrast enhancement (Fig 1 C, -D). At this time, the CD4 cell count increased to 495 cells/mL, and the HIV-1 RNA load decreased to 768 copies/mL. A stereotactic brain biopsy of the left frontal lobe lesion revealed reactive gliosis, collections of histiocytic giant multinucleated cells, and marked perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates with a predominance of CD8 lymphocytes. No fungal elements were identified on periodic-acid-Schiff or Grocott stains; no toxoplasma pseudocysts, tachyzoites, or cytopathic changes were seen in neuronal or glial cells suggestive of infection by CMV, HSV, or JCV. A culture for mycobacterial organisms or fungi was also negative. About a month after the biopsy, even without using steroids, the patient showed significant improvement in clinical status, fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for cerebral toxoplasmosis associated with IRIS.

IRIS is a paradoxic worsening or onset of systemic inflammatory clinical signs and symptoms among patients with HIV/AIDS. It occurs after the initiation of HAART, particularly in those patients with profound immune suppression, and can occur with or without a concurrent opportunistic infection. Whether elicited by an infectious or noninfectious agent, the presence of an antigenic stimulus for development of the syndrome appears necessary. This antigenic stimulus can be intact “clinically silent” organisms or dead organisms and their residual antigens.1–4 Conventional and advanced MR imaging techniques are useful in evaluating these phenomena. Typical MR imaging patterns of some infections can be modified during IRIS. The most frequent findings are a paradoxic increase in the size and number of lesions, perilesional edema, and greater enhancement in T1-weighted images post–gadolinium administration. A combination of clinical, laboratory, and MR imaging findings with follow-up studies is recommended in these patients. The use of MR imaging in association with clinical and laboratory data can reduce the number of unnecessary cerebral biopsies in these clinical scenarios.

Contributor Information

E.L. Gasparetto,

L. Chimelli,

References

- 1. Murdoch DM, Venter WD, Van Rie A, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS): review of common infectious manifestations and treatment options. AIDS Res Ther 2007;4:9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thurnher MM, Post MJ, Rieger A, et al. Initial and follow-up MR imaging findings in AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2001;22:977–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pfeffer G, Prout A, Hooge J, et al. Biopsy-proven immune reconstitution syndrome in a patient with AIDS and cerebral toxoplasmosis. Neurology 2009;73:321–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tremont-Lukats IW, Garciarena P, Juarbe R, et al. The immune inflammatory reconstitution syndrome and central nervous system toxoplasmosis. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:656–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]