SUMMARY:

Ganglionic eminence is the main transitory proliferative structure of the ventral telencephalon in human fetal brain and it contributes for at least 35% to the population of cortical interneurons; however data on the human GE anomalies are scarce. We report 5 fetal MR imaging observations with bilateral symmetric cavitations in their GE regions resembling an inverted open C shape and separating the GE itself form the deeper parenchyma. Imaging, neuropathology, and follow-up features suggested a malformative origin. All cases had in common characteristics of lissencephaly with agenesis or severe hypoplasia of corpus callosum of probable different genetic basis. From our preliminary observation, it seems that GE cavitations are part of conditions which are also accompanied by severe cerebral structure derangement.

The ganglionic eminence is a transitory proliferative structure of the ventral telencephalon localized in human fetal brain along the lateral walls of the frontal (and to a less extent the temporal) horns of the lateral ventricles. During development, the GE persists longer than other proliferative areas and only by term has nearly disappeared. The GE contains precursor neurons of the basal ganglia and amygdala; it also contributes at least 35% to the population of interneurons that tangentially migrate toward to the cerebral cortex1,2 and to a population of the thalamic neurons. In rodents, the medial GE represents the major source of the cortical interneurons; the caudal GE is an additional source of tangentially migrating interneurons to the cortex and hippocampus and the lateral GE is the major source of striatal gamma-aminobutyric acid projection neurons. Although data in humans are scant, the partition of GE has been recently proposed.3,4 The GE also represents an intermediate target for corticofugal and thalamocortical axons.5

Despite the pivotal importance of the GE in human brain development, data on GE anomalies are scarce, for example, the recent report on hemorrhage occurring in this region in premature babies.6

Recently in our institution, in a clinical fetal MR imaging observation, we found bilateral symmetric cavitations in the GE region. To better understand the significance of this unusual finding, we then set out to analyze similar cases possibly present in our prenatal MR imaging data base. We found 4 additional fetal cases, all of which also had bilateral symmetric cavitations in the GE regions (probably of malformative origin). All 5 cases also had in common characteristic features of lissencephaly with agenesis or severe hypoplasia of the corpus callosum of probable different genetic basis.

The main purpose of this report is to present the imaging and, when available, pathology data of this rare finding.

Materials and Methods

From our 10-year prenatal MR imaging data base (containing approximately 2200 cases), we collected 5 fetal cases (22, 29, 23, 22, and 25 weeks of gestational age, respectively; 4 female and 1 male) with reported “cavitations or cysts in the GE-basal ganglia region.” Two of these cases had familial recurrence (cases 2 and 3 in On-line Table 1).

All 5 MR imaging studies had been performed for clinical purposes, after expert sonography study. All mothers had signed the specific consent form for fetal MR imaging in use at our institution, and the study complied with the internal guidelines for clinical retrospective studies used at our institution.

Follow-up data analysis was based on the following methods (On-line Table 1): 2 cases (case 1 and 4) after pregnancy termination underwent pathology examination, 1 case (case 3) after pregnancy termination was studied solely by MR-autopsy, 1 case (case 2) underwent neonatal MR imaging, and 1 pregnancy (case 5) was terminated outside of our institution without available autopsy or MR autopsy data.

MR Imaging Methods

A 1.5T scanner was used for fetal MR imaging, with a phasedarray abdominal or cardiac coil. All the selected 5 cases had been investigated through T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo multiplanar sections: 3–4-mm section thickness, TR/TE 3000/180 ms, 1.1 mm2 in-plane resolution; in some cases BALANCE 2–3-mm thick sections were also acquired (Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, the Nerthlands). In the 2 most recent cases (cases 1 and 4), T1-weighted FSE 5.5-mm-thick sections (TR/TE = 300/14 ms, turbo factor = 3, 1.4 mm2 in-plane resolution) and diffusion-weighted imaging 5.5-mm-thick sections (TR/TE = 1000/90 ms, b factor = 0–600 seconds/mm2, FOV = 320 × 320 mm, matrix = 128 × 128) were also available.

Two senior pediatric neuroradiologists (A.R., C.P.), with 12 years of experience in fetal MR imaging, evaluated the images in consensus.

MR-autopsy and neonatal MR imaging studies were performed with the use of a neonatal dedicated head coil and 1.5T scanner; 2–3-mm-thick T2-weighted FSE sequences (TR/TE 6000/200 ms), with 0.3 mm2 in-plane resolution, were acquired.

Pathology Methods

The autopsy brains from cases 1 and 4 (On-line Table 1) were fixed in 10% formalin, subsequently embedded in paraffin, and cut in 10-μm-thick coronal sections. Sampled sections of the anterior part of the brain, at the level of the GE, were stained with thionin (0.1% in distilled water) and hematoxylin and eosin and examined with the use of an Aperio Image Scope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Additional series of sections were cut and processed for immunolocalization of the neuronal calcium-binding proteins calbindin and calretinin, of the intermediate filament protein vimentin, which is early-expressed in the radial glia. After incubation in 10% (volume-volume percent) normal serum to mask nonspecific adsorption sites, sections were processed with the use of the following primary antibodies: polyclonal anti-Calbindin (1:600; Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland), polyclonal anti-Calretinin (1:300; Swant), and monoclonal anti-Vimentin (1:200, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). Unfortunately, the scanty preservation of tissue caused by the autolytic processes hampered a reliable result of immunohistochemistry. Thus, only routine histologic staining was reliably used for neuropathologic examination.

Genetic Analysis

DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from cases 1 and 4 by use of the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Mutation analysis of the LIS1 (genebank accession: NM_000430.3) and TUBA1A (genebank accession: NM_006009.2) genes, known to be involved in lissencephalies, was performed by direct sequencing. No mutations were identified. Unfortunately, genomic rearrangements involving the LIS1 gene could not be excluded by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis because of poor DNA quality. Sequence analysis of the ARX gene could not be performed either, because of the poor quality of DNA and the high guanine-cytosine content of this gene.

Results

The findings reported in expert sonography examinations (On-line Table 1) were CC agenesis in all 5 cases, as well reduced cranial and cerebellar biometry, mild-moderate ventriculomegaly in 3 cases, and reduced whole-body biometry in 2 cases. None of the sonography reports mentioned basal ganglia region cavitations.

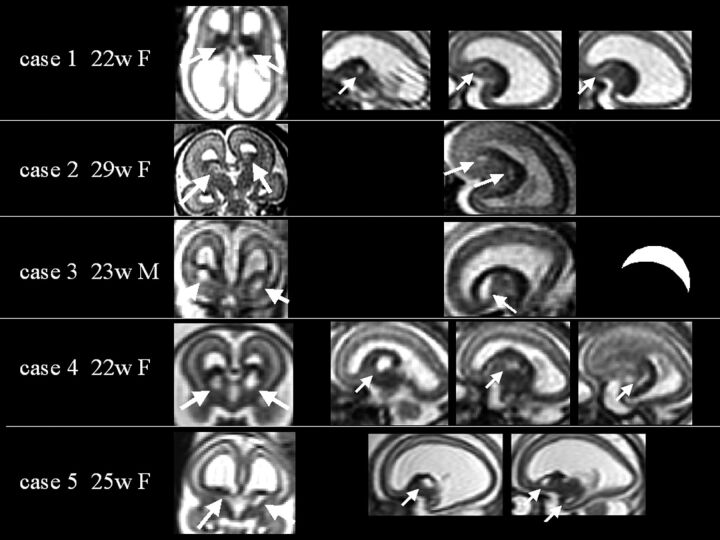

At prenatal MR imaging, all 5 cases displayed bilateral symmetric cavitations in the GE region, separating the GE itself from the deeper parenchyma and resembling an inverted open C shape (Fig 1). In 2 cases (cases 2 and 4), GE appeared to be clearly larger than in healthy controls at the same GA (On-line Fig 1). In T1-weighted and diffusion-weighted imaging (available exclusively in cases 1 and 4), the GE showed a hyperintensity comparable to that of the periventricular-germinal matrix area and slightly higher than that of the cortical plate (On-line Fig 2); however, the associated apparent diffusion coefficient tended to be slightly lower (0.85 SD, 0.09 μm2/s) than in GE of healthy controls (0.95 SD, 0.13 μm2/s, unpublished data).

Fig 1.

Prenatal single-shot FSE T2-weighted MR images of the 5 reported cases, each case displayed horizontally in a row. Case number, GA, and sex are reported. White arrows indicate GE region cavitations. In the case 3 row, an inverted open C shape is drawn, showing how cavitation appears on sagittal sections. The corpus callosum is agenetic or severely hypoplastic in all cases. Frontal opercula are shallow and dysmorphic.

All 5 cases demonstrated reduction of biometric brain parameters (below the 10th percentile with respect to normal data of reference7) (On-line Table 1), agenesis or severe hypoplasia of the CC, and defective gyration such as shallow opercula and absent/reduced parieto-occipital sulcus (normally visible before the 23 weeks of GA). One case (case 2) had bilateral frontal band heterotopias (Fig 3), confirmed by neonatal MR imaging. No case showed a disproportionate reduction of the pontine bulging.

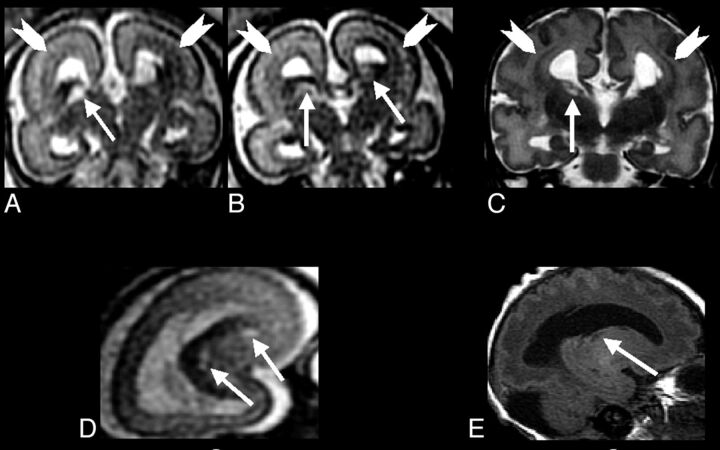

Fig 3.

A–C, Single-shot FSE T2-weighted sections from case 2 (29-week GA) prenatal study shows GE region cavitations (arrows), which tend to be relatively smaller with respect to the brain size in this older fetus. Arrowheads indicate bilateral bands of heterotopias. Gyration appears to be poor. D, Coronal FSE T2-weighted and sagittal (E) spin-echo T1-weighted sections show cavitations now relatively smaller and confirming band heterotopias (arrowheads).

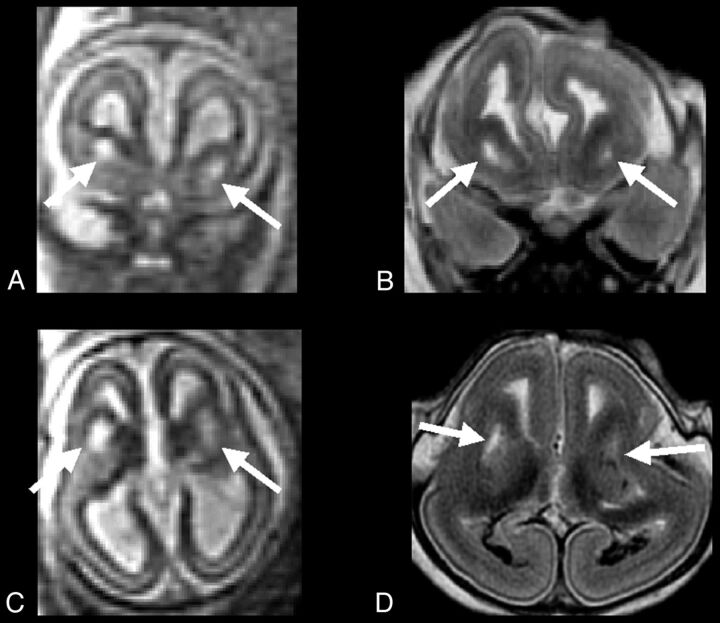

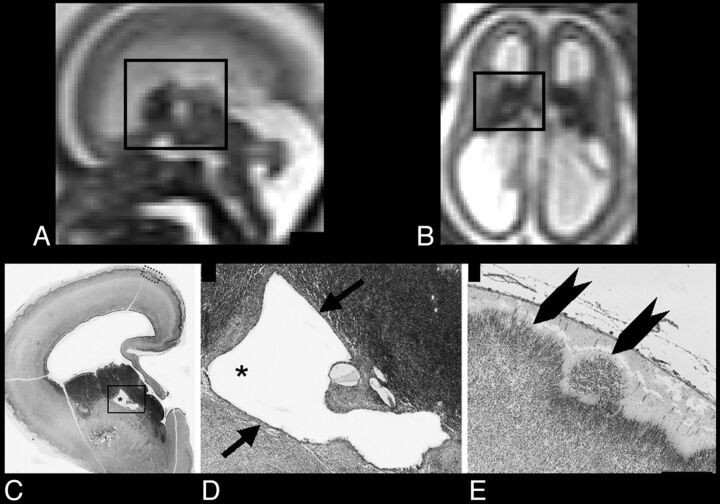

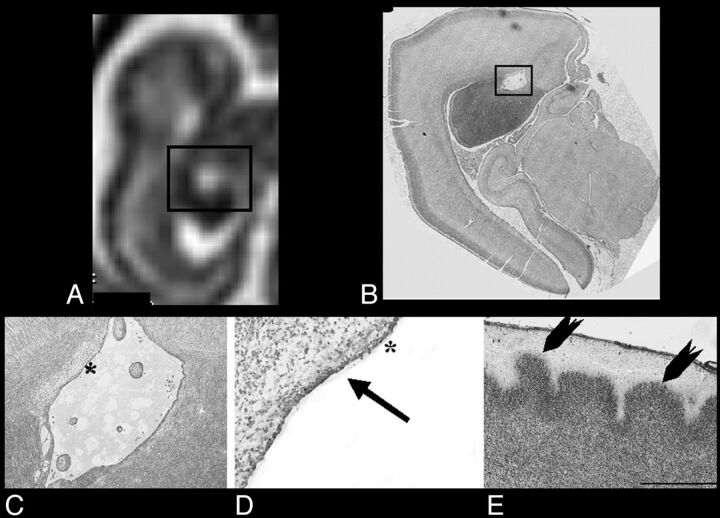

MR autopsy (case 3, Fig 4), pathology (cases 1 and 4, Figs 2 and 5), and neonatal MR imaging (case 2, Fig 3) confirmed the presence of lissencephaly. Furthermore, in all cases, lesions were symmetric; they appeared to be lined by an epithelium-like structure at pathologic examination (cases 1 and 4), and cavitation margins were regular, without apparent signs of previous or ongoing hemorrhage.

Fig 4.

A and C, Single-shot FSE T2-weighted sections from case 3 (23-week GA) prenatal study, show large symmetric GE region cavitations (arrows). B and D, FSE T2-weighted corresponding MR autopsy sections, which confirm the prenatal findings (arrows): cavitations appear to have regular smooth margin, albeit brain was compressed and deformed during delivery.

Fig 2.

A and B, Sagittal and axial single-shot FSE T2-weighted sections of case 1 (22-week GA), respectively: black rectangle encompasses GE and relative cavitation. C, Thionin-stained paraffin coronal section shows a hemisphere at the level of GE cavitation (asterisk). D, Higher magnification of the black rectangle area in C, illustrating the regular border (epithelium-like structure) of cavitation (arrows). E, Higher magnification of the cortex (dotted rectangle in C): heterotopic cortical plate neurons extending in the marginal zone (arrowheads). Scale bar = 300 μm.

Fig 5.

A, Coronal single-shot FSE T2-weighted section from case 4 (22-week GA); brain is shown upside-down to better match the corresponding coronal oblique histologic section in B, Thionin-stained paraffin section with black rectangle encompassing part of GE and related cavitation; C, higher magnification of the black rectangle in B; D, inside part of the cavitation (asterisks in C and D) lined by epithelium-like structure (arrow); E, detail of the developing cortex shows heterotopic cortical plate neurons extending in the marginal zone (arrowheads). Scale bar = 410 μm.

In addition, both cases, in which histology was available (cases 1 and 4) demonstrated a disorganization of the developing cortex. In particular, the cortical plate surface appeared to be irregular, with heterotopic cellular extension into the marginal zone (Figs 2 and 5). None of the cases presented at autopsy (cases 1, 3, and 4) or at clinical examination after birth (case 2) had ambiguous genitalia, which could be related to some type of lissencephaly such as the one X-linked ARX gene.

Discussion

From our preliminary observation, it appears that GE cavitations are an aspect of more complex conditions associated with severe cerebral structural derangement. The awareness of this rare developmental abnormality involving the GE region may have implications in better understanding of the complex malformations caused by defective cellular proliferation and migration, such as lissencephalies. The fact that the lesions were bilateral and symmetric with an inverted “regular” open C shape, an epithelium-like lining, regular margins, and no apparent signs of hemorrhage (including the 2 cases with T1-weighted images) suggests a malformative rather than necrotic-clastic origin. Familial recurrence in 2 cases and the presence of frontal band heterotopias in 1 case further support such a hypothesis. Although the data are not extensive enough to conclude a statistical significance, the available ADC values (cases 1 and 4), albeit showing a slight trend toward mild reduction (0.85 SD, 0.09 m2/s), remained higher than ADC values reported in fetal brain acute ischemia cases (ie, 0.4 m2/s in Righini et al8). Moreover, in the case illustrated in On-line Fig 2, GE histology showed a higher cell body/interstitial space ratio (a possible sign of structural developmental anomaly) but not signs of acute cytotoxic edema (such as neuropil swelling). Nevertheless, because we do not have detailed histologic data for all of our cases, we cannot completely rule out the necrotic nature of the observed GE region cavitations. Moreover, the existence of a recent report,9 which showed basal ganglia vasculopathy in a lissencephaly case, further warns of the possibility that ischemia may play a role in cavitation onset.

According to Barkovich et al,10 lissencephalies are primarily caused by abnormal neuronal migration. In such conditions, abnormal development of the GE, together with deficiency of other fetal transient structures such as the germinal matrix, may play a key role. We may speculate that cavitations associated with GE might derive from abnormal proliferation of neural precursors in the region and subsequently affect migration of inhibitory interneurons from GE toward their final cortical destination. However, detailed cytologic-immunohistochemical assessment could not be performed in our cases because of faulty tissue preservation. However, the cystic anomaly of the GE region might contribute to causing lissencephaly even by simply physically affecting cell migration, even in the absence of proliferation defect, because, in at least 2 of our cases, GE was larger than in healthy controls of the same GA.

The presence in our 5 cases of opercularization defects, agenesis-severe hypoplasia of CC, abnormal cortical plate findings at histology, and heterotopic bands, further supports the hypothesis that GE cavitation anomalies are part of complex malformations, which involve cell migration and possibly a cell differentiation phase.

To the best of our knowledge, GE cavitations have not been described in animal models of lissencephaly; neither have they been reported in the existing extensive postnatal neuroimaging literature regarding human lissencephalies. This could be explained by their size decrease as the whole brain progressively grows. In postnatal MR studies, cavitation remnants might have been occasionally interpreted in the past just as enhanced perivascular spaces in the basal ganglia region; cavitations may relatively decrease in size with respect to the progressive growth of the whole brain.

A major limitation of our report is the lack of substantial molecular genetics characterization of our cases. Banded karyotyping, which turned out to be normal, was available in 3 cases (On-line Table 1); however, karyotyping is usually of limited diagnostic power in lissencephaly. Molecular study of the X-linked gene ARX, which was not possible, might have been indicated in cases 2 and 3, although the severe phenotype observed in the sister and parental consanguinity makes it unlikely to be an X-linked inheritance. Converging experimental, neuropathologic, and imaging evidence suggests that mutations in this gene cause an abnormal developmental process primarily affecting GE development. Impaired proliferation of neuronal elements in the GE and subsequent abnormal proliferation of GABAergic interneurons has been demonstrated in the ARX knock out model.11 Microcystic changes in the basal ganglia are observed in the brains of children with X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia, both at neuropathology12 and by use of MR imaging scan.13 Multiple small areas of abnormal signal intensity, possibly representing microcystic changes, are observed in the basal ganglia of boys with ARX mutations and profound cognitive impairment but no lissencephaly.14

Albeit limited by the rarity of these findings and by the difficulty of histology studies on fetal human brain before the third trimester of GA, additional cases investigated by cytologic labeling of GE-originating neuroblasts and cortical interneurons are needed to further elucidate the meaning of the anomaly we have reported and to definitively rule out the possibility of a lesional etiology.

Supplementary Material

ABBREVIATIONS:

- CC

corpus callosum

- GA

gestational age

- GE

ganglionic eminence

REFERENCES

- 1.Letinic K, Zoncu R, Rakic P. Origin of GABAergic neurons in the human neocortex. Nature 2002;417:645–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zecevic N, Hu F, Jakovcevski I. Interneurons in the developing human neocortex. Dev Neurobiol 2011;71:18–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbin JG, Gaiano N, Juliano SL, et al. Regulation of neuronal progenitor cell development in the nervous system. J Neurochem 2008;106:2272–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Métin C, Baudoin JO, Rakic S, et al. Cell and molecular mechanisms involved in the migration of cortical interneurons. Eur J Neurosci 2006;23:894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulfig N. Ganglionic eminence of the human fetal brain: new vistas. Anat Rec 2002;267:191–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Bigio MR. Cell proliferation in human ganglionic eminence and suppression after prematurity-associated haemorrhage. Brain 2011;134:1344–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parazzini C, Righini A, Rustico M, et al. Prenatal magnetic resonance imaging: brain normal linear biometric values below 24 gestational weeks. Neuroradiology 2008;50:877–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Righini A, Kustermann A, Parazzini C, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of acute hypoxic-ischemic cerebral lesions in the survivor of a monochorionic twin pregnancy: case report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;29:453–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagla M, Kruczek P, Kwinta P. Association between X-linked lissencephaly with ambiguous genitalia syndrome and lenticulostriate vasculopathy in neonate. J Clin Ultrasound 2008;36:387–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkovich AJ, Guerrini R, Kuzniecky RI, et al. A developmental and genetic classification for malformations of cortical development: update 2012. Brain 2012;135:1348–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura K, Yanazawa M, Sugiyama N, et al. Mutation of ARX causes abnormal development of forebrain and testes in mice and X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia in humans. Nat Genet 2002;32:359–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonneau D, Toutain A, Laquerrière A, et al. X-linked lissencephaly with absent corpus callosum and ambiguous genitalia (XLAG): clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and neuropathological findings. Ann Neurol 2002;51:340–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato M, Das S, Petras K, et al. Mutations of ARX are associated with striking pleiotropy and consistent genotype-phenotype correlation. Hum Mutat 2004;23:147–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrini R, Moro F, Kato M, et al. Expansion of the first PolyA tract of ARX causes infantile spasms and status dystonicus. Neurology 2007;69:427–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.