Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

In asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD, the risk of ischemic events is low in general, but there may be a subgroup of higher risk patients who require aggressive medical management. The purpose of this study was to determine whether chronic hemodynamic compromise is a predictor of ischemic events in asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We prospectively studied 51 asymptomatic, 19 coexistent asymptomatic, and 19 remote (>6 months) symptomatic patients with atherosclerotic intracranial internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery disease by using 15O-PET. MP was defined as decreased CBF, increased OEF, and a decreased CBF/CBV ratio. All patients were followed up for 2 years or until occurrence of stroke or TIA or death.

RESULTS:

Bypass surgery was performed in 4 patients (2 with MP). Three cerebral ischemic events (1 TIA in an asymptomatic patient, 1 stroke, and 1 TIA in a remote symptomatic patient) occurred in the vascular territory ipsilateral to LAICOD. Kaplan-Meier analysis with censoring at the time of bypass surgery revealed that the incidence of ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with MP (2/5) was significantly higher than that in patients without MP (1/84) (log-rank test; P < .0001). The relative risk conferred by MP was 83.1 (95% confidence interval, 6.8–1017.4; P < .001). The incidence of ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with decreased CBF/CBV (2/9) was also significantly higher than that of patients without it (1/80) (P = .0001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Chronic hemodynamic compromise may be a predictor of ischemic events in both asymptomatic and remote symptomatic LAICOD.

LAICOD has emerged as the most common stroke subtype worldwide, and recent symptomatic LAICOD (within 3 months) is associated with a high risk of recurrent stroke.1,2 Aggressive medical management is recommended to prevent recurrent stroke for this subset of high-risk patients.3 On the other hand, in asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD, the risk of ischemic events is relatively low.4,5 If a patient has asymptomatic LAICOD or presents for evaluation after the initial symptoms and does not experience subsequent events, a more conservative approach is recommended. However, there may be a subgroup of higher risk patients who require aggressive medical management.

Hemodynamic factors may be important in LAICOD prognosis.6–9 Patients with LAICOD with hemodynamic symptoms were reported to be at high risk for subsequent ischemic events.10 Previous studies of mixed patient populations with symptomatic large-artery extracranial and intracranial occlusive disease suggest that chronic hemodynamic compromise, as indicated by increased OEF (also known as MP)11 on 15O-PET12 or severely decreased vasodilatory capacity, is a risk factor for subsequent ischemic stroke.13–17 However, the relationship between hemodynamic compromise and asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD prognosis is unknown. The purpose of this observational study was to determine whether chronic hemodynamic compromise on 15O-PET is a predictor of subsequent ischemic events in asymptomatic or remote (>6 months) symptomatic atherosclerotic intracranial disease of the ICA or MCA.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We studied 51 consecutive patients with asymptomatic atherosclerotic LAICOD (asymptomatic group). We included 31 men and 20 women (age range, 44–90 years; mean, 63 ± 9 years; Table 1). Patients were first referred to the PET unit at Shiga Medical Center from the outpatient clinic or other hospitals in the Shiga Prefecture between 1999 and 2008 to undergo hemodynamic parameter evaluation as part of clinical assessment to determine the need for extracranial–intracranial bypass. Although the benefit from bypass surgery in patients with MP remains to be proved, the operation is nevertheless performed in some patients in Japan and elsewhere. The inclusion criteria were the following: 1) occlusion or stenosis (>50% diameter reduction) of the intracranial ICA or MCA as documented by conventional or MR angiography,18 and 2) absence of previous symptoms or signs of ischemia in the diseased intracranial ICA or MCA territory. The exclusion criteria were the following: 1) history of vascular reconstruction surgery, or 2) potential sources of cardiogenic embolism, including recent myocardial infarction (within 3 weeks), known atrial fibrillation, mitral stenosis, mitral valve prosthesis, dilated cardiomyopathy, sick sinus syndrome, or subacute bacterial endocarditis.

Table 1:

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Category |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | Coexistent | Remote | Controls | |

| No. of patients | 51 | 19 | 19 | 7 |

| MP (No.) | 1 | 1 | 3 | – |

| Increased OEF | 7 | 4 | 6 | – |

| Decreased CBF/CBV | 1 | 3 | 5 | – |

| Age (mean) (yr) | 63 ± 9 | 63 ± 9 | 65 ± 8 | 47 ± 7 |

| Men/women (No.) | 31:20 | 13:6 | 13:6 | 4:3 |

| Cerebral infarction (No.). | 20 | 7 | 17 | – |

| Asymptomatic bilateral lacunar infarcts (No.) | 8 | 3 | 3 | – |

| Qualifying artery (No. of occlusions/stenoses) | 9/42 | 5/14 | 7/12 | – |

| Intracranial ICA (occlusions/stenoses) | 26 (3/23) | 9 (1/8) | 4 (1/3) | – |

| MCA (occlusion/stenosis) | 25 (6/19) | 10 (4/6) | 15 (6/9) | – |

| Other asymptomatic stenoses >50% (No.) | 18 | – | 2 | – |

| Other medical illness (No.) | ||||

| Hypertension | 27 | 11 | 15 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 | 10 | 5 | 0 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 9 | 7 | 4 | 0 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 10 | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| Smoking habit (current and former) (No.) | 11 | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 33 | 18 | 17 | 0 |

| Bypass surgery (MP) (No.) | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | – |

Note:—Asymptomatic indicates asymptomatic artery disease; Coexistent, coexistent asymptomatic artery disease; Remote, remote symptomatic artery disease.

During the same study period, we also studied 19 consecutive patients with asymptomatic LAICOD coexistent with symptomatic large-artery disease who met the inclusion criteria above (coexistent group) and 19 consecutive patients with remote (>6 months; median, 45 months; range, 6.4–142 months) symptomatic LAICOD without subsequent events (remote group) (Table 1). These patients were selected from candidates for the observational study of symptomatic large-artery disease reported elsewhere.17 Patients were first referred to the PET unit at Shiga Medical Center from the outpatient clinic or other hospitals in the Shiga Prefecture to undergo hemodynamic parameter evaluation as part of clinical assessment to determine the need for bypass surgery. The inclusion criteria for symptomatic large-artery disease were the following: 1) occlusion of the extracranial ICA or occlusion or stenosis (>50% diameter reduction) of the intracranial ICA or MCA as documented by conventional or MR angiography,18 2) history of TIA or stroke involving the relevant ICA or MCA territory, and 3) ability to independently carry out daily activities (<3 on the modified Rankin Scale). The exclusion criteria were the same as described above.

In asymptomatic (never symptomatic) patients, arterial disease was suspected on the basis of the findings of MR angiography or echo angiography performed during screening for cerebral arterial disease in patients with coronary artery disease or those presenting with dizziness, vertigo, or headache. In 20 of the 51 patients, MR imaging revealed minor abnormalities in the MCA territory of the hemisphere with arterial disease. Eight patient MRIs showed asymptomatic lacunar infarcts in the bilateral basal ganglia (putamen, globus pallidus, and caudate nucleus) that were identified as hyperintense regions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images and hypointense areas on T1-weighted images. Diseased arteries included intracranial ICA occlusion in 3 cases, intracranial ICA stenosis in 23 cases, MCA occlusion in 6 cases, and MCA stenosis in 19 cases. Other asymptomatic arterial stenoses (>50% diameter reduction)18,19 were found in 16 cases (18 arteries), including contralateral ICA disease in 8 cases, contralateral MCA disease in 4 cases, and vertebral artery disease in 6 cases. The findings on MR imaging or angiography in coexistent asymptomatic or remote symptomatic patients are listed in Table 1. Vascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking status were determined from patient history recorded at the time of PET examination. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, and hypercholesterolemia were judged as present on the basis of treatment history. The ethics committee of our center approved the study protocol, and each patient provided written informed consent.

PET Measurements

All patients underwent 15O-PET scans with a whole-body Advance PET scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin), which permits simultaneous acquisition of 35 sections with intersection spacing of 4.25 mm.20 Intrinsic scanner resolution was 4.6–5.7 mm in the transaxial direction and 4.0–5.3 mm in the axial direction. As part of the scanning procedure but before tracer administration, germanium 68/gallium 68 transmission scanning was performed for 10 minutes for attenuation correction. To reconstruct the PET data, we blurred images to 6.0-mm full width at half maximum in the transaxial direction with a Hanning filter. Functional images were reconstructed as 128 × 128 pixels, with each pixel representing an area of 2.0 × 2.0 mm.

A series of oxygen 15 (15O) gas studies was performed. The patients continuously inhaled C15O2, and 15O2 through a face mask.20 The scanning time was 5 minutes, and arterial blood was manually sampled from the brachial artery 3 times during each scan. Radiotracer radioactivity in whole blood and plasma was measured by using a well counter. Bolus inhalation of C15O and 3-minute scanning was used to measure CBV. Arterial samples were manually obtained twice during scanning, and radiotracer radioactivity was measured in whole-blood samples. CBF, CMRO2, and OEF were calculated by using the steady-state method.21 CMRO2 and OEF were corrected by CBV.22 The CBF/CBV ratio was calculated pixel-by-pixel as an indicator of cerebral perfusion pressure.23

Data Analysis

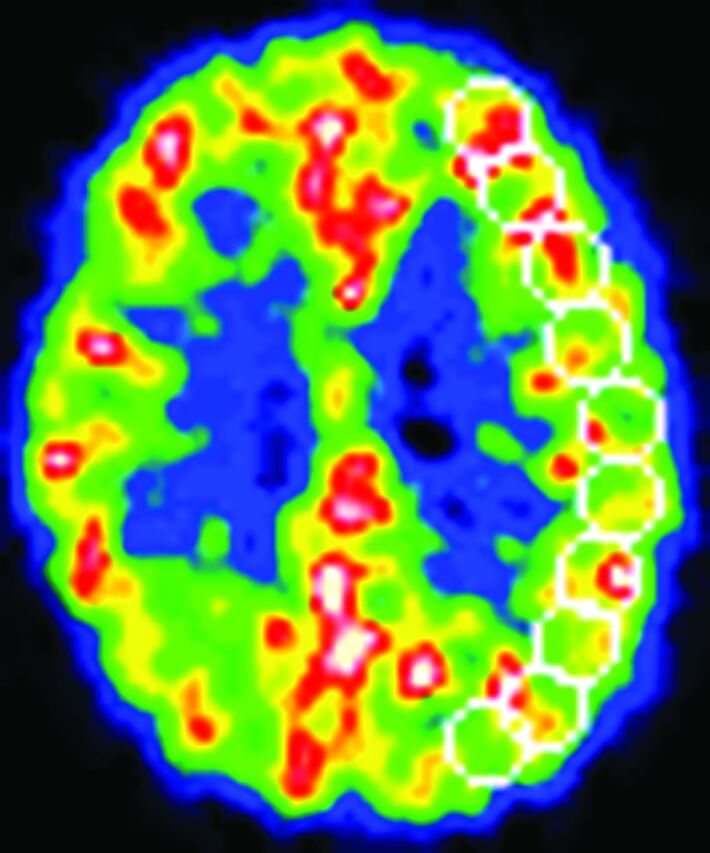

We analyzed 10 tomographic planes from 46.25 to 84.5 mm above and parallel to the orbitomeatal line, which corresponded to the levels of the basal ganglia and thalamus to the centrum semiovale. The ROIs were placed on the CBF images. Each image was examined by placing 10–12 circular ROIs (diameter, 16 mm) over the outer cortical gray matter in each hemisphere (Fig 1). According to the atlas, the ROIs in all 10 images covered the distribution of the MCA and the watershed areas between the MCA and other cerebral arteries.24 The same ROIs were transferred to the other images. The mean value for the hemisphere affected by ICA or MCA disease was calculated as the average of the values for all circular ROIs. In asymptomatic (never symptomatic) patients with bilateral disease, the hemisphere supplied by the more severely diseased ICA or MCA is referred to here as the “affected hemisphere.” In patients with cerebral cortex infarction, the circular ROIs that included hypointense areas on T1-weighted MR images were excluded from analysis by using a method that correlated PET images with MR images.16 We did not use coregistered MR imaging to define the ROIs.

Fig 1.

An example of the ROIs on the CBF image.

Normal control values of the 15O-PET variables were obtained from 7 healthy volunteers (4 men and 3 women; mean age, 47 ± 7 years) who underwent routine neurologic examinations and MR imaging scans. The OEF value obtained from these 14 control hemispheres was 44.5% ± 3.8%. Hemispheric OEF values beyond the upper 95% limit defined in healthy subjects (above 52.9%) represented increased OEF. Comparative values for CBF and CBF/CBV in healthy controls were 44.6 ± 4.5 and 11.4 ± 1.8, respectively. Hemispheric CBF and CBF/CBV values below 35.0 mL/100 g/min and 7.6/min, respectively, were considered abnormal.

Patients with increased OEF, decreased CBF, and decreased CBF/CBV in hemispheres with arterial disease were categorized as having MP. This definition differed from that in our previous study, which only considered increased OEF.15,16 It was adopted because increased OEF without decreased perfusion pressure may not indicate MP.17,23 Patients with increased OEF in our previous study also had decreased CBF and CBF/CBV,15 which is consistent with MP in the present study. Patients were categorized as having or not having MP by an investigator who was unaware of their clinical status.

Follow-Up and Outcome

Attending physicians were informed of 15O-PET findings, but risk factor treatment and pharmacologic or surgical interventions were left to individual clinical judgment. Asymptomatic patients who received medical treatment and all symptomatic patients were examined at 1- or 2-month intervals after 15O-PET in the outpatient clinic of our center or at other hospitals in the Shiga Prefecture. An interim history was obtained, and a neurologic examination was performed at each visit. We contacted 2 asymptomatic patients without medical treatment or their next of kin by telephone every 6 months. In patients who experienced subsequent ischemic events (stroke or TIA), MR images or CT images were obtained and compared with the initial images to confirm stroke, and MR angiography was performed to study changes in arterial disease. The end point was an ipsilateral ischemic event (stroke or TIA). “Stroke” was defined as the acute onset of a new focal neurologic deficit of cerebral origin persisting for more than 24 hours without primary intracranial hemorrhage on CT or MR imaging. “TIA” was defined as the development of focal symptoms of presumed cerebrovascular ischemic origin lasting <24 hours.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline values of 5 PET variables were compared among 3 LAICOD types and healthy controls by using 1-way analysis of variance and post hoc Scheffe analysis; significance was established at P < .01 (.05/5) by performing a Bonferroni correction. The incidence of subsequent cerebral ischemic events was compared between groups by using the Fisher exact test or Mantel-Cox log-rank statistics and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Survival analysis began on the day of the 15O-PET examination, which was considered the date of entry into the study. Analysis was performed with censoring at the time of bypass surgery. Multivariate analysis by using the Cox proportional hazards model was used to test the effect of multiple variables on the occurrence of ischemic events. Age, sex, subgroup (asymptomatic, coexistent asymptomatic, or remote symptomatic LAICOD), antiplatelet agent, arterial occlusion, MCA disease, other asymptomatic major cerebral arterial stenoses, cerebral infarction, bilateral asymptomatic lacunar infarcts, complications (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prior ischemic heart disease, or hypercholesterolemia), smoking habits, and MP were considered covariates. Forward stepwise selection was performed, and variables demonstrating a significant relationship (P < .05) with an outcome event were included in the final model.

Results

On the basis of OEF, CBF, and CBF/CBV values in the hemisphere supplied by the asymptomatic or remote symptomatic artery, 5 patients (5.6%) had MP and 84 did not (Table 1). Seventeen patients had increased OEF, while 9 patients had decreased CBF/CBV. Baseline values of PET variables in the 3 groups are shown in Table 2. No significant difference was found for any variable among the 3 patient groups, while CBF in remote symptomatic patients was only significantly decreased compared with healthy controls.

Table 2:

Baseline values of PET variables in the hemispheres ipsilateral to intracranial artery disease and in healthy controlsa

| Variable | Category |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | Coexistent | Remote | Controls | |

| CBF (mL/100 g/min) | 39.5 ± 7.3 | 36.3 ± 7.8 | 34.0 ± 6.6b | 44.6 ± 4.5 |

| CMRO2 (mL/100 g/min) | 3.29 ± 0.50 | 2.96 ± 0.44 | 2.89 ± 0.42 | 3.43 ± 0.33 |

| OEF (%) | 48.0 ± 5.9 | 50.7 ± 6.8 | 50.3 ± 5.8 | 44.5 ± 3.8 |

| CBV (mL/100 g) | 3.53 ± 0.54 | 3.85 ± 0.83 | 3.84 ± 0.75 | 3.98 ± 0.48 |

| CBF/CBV (per min) | 11.3 ± 2.1 | 9.8 ± 2.7 | 9.2 ± 2.6 | 11.4 ± 1.8 |

Note:—Asymptomatic indicates asymptomatic artery disease; Coexistent, coexistent asymptomatic artery disease; Remote, remote symptomatic artery disease.

Values are means.

P < .001 vs corresponding value in healthy controls (1-way ANOVA and post hoc Scheffe analysis).

All patients were followed up for 2 years or until a cerebral ischemic event or death. Four patients (4.5%), including 2 with MP (1 intracranial ICA stenosis and 1 intracranial ICA occlusion) and 2 without (2 MCA occlusions), underwent bypass surgery an average of 2.4 months after PET examinations (range, 0.5–4.0 months). Three cerebral ischemic events occurred in the vascular territory ipsilateral to LAICOD. All 3 events occurred in medically treated patients. One stroke and 1 TIA occurred in remote symptomatic patients with remote artery disease and MP; 1 patient with left intracranial ICA stenosis developed infarction in the posterior limb of the left internal capsule, resulting in right hemiparesis; and 1 patient with left MCA stenosis developed a transient episode of sensory aphasia (Fig 2). One TIA occurred in an asymptomatic patient without MP, and a patient with right MCA occlusion developed a transient weakness of the left upper limb. Four surgically treated patients had no ischemic events after surgery. All of the asymptomatic or remote symptomatic patients survived the 2-year follow-up period, and 1 patient with coexistent asymptomatic artery disease and MP died of myocardial infarction after 12 months.

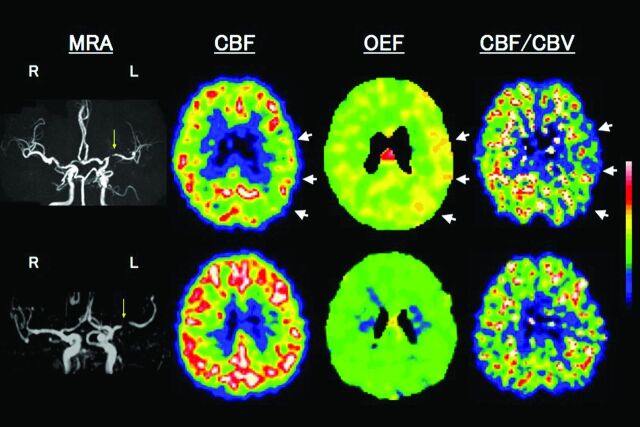

Fig 2.

Upper row shows examples of PET images for a patient with left (L) remote (41 months) symptomatic MCA stenosis with MP. MRA shows severe stenosis of the L MCA. PET study shows reduced CBF, increased OEF, and decreased CBF/CBV in the L hemisphere with MCA stenosis (arrows). A subsequent transient ischemic attack (a transient episode of sensory aphasia) occurred 14 days after the PET study. Lower row shows a patient with L asymptomatic MCA stenosis with normal cerebral hemodynamics.

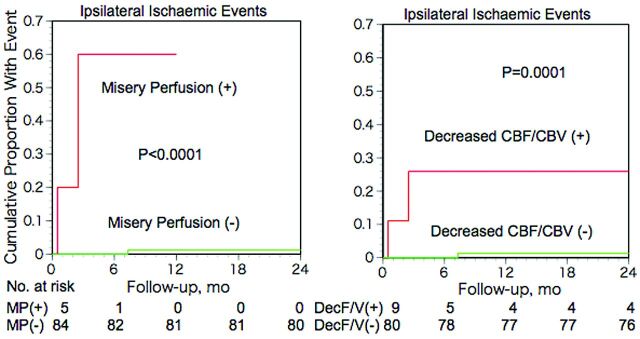

In patients with and without MP, the 2-year incidences of ipsilateral stroke and TIA were 2/5 (40%) and 1/84 (1.2%), respectively (Fisher exact test; P = .0075). Kaplan-Meier analysis with censoring at the time of bypass surgery revealed that the incidence of ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with MP was significantly higher than that of patients without MP (P < .0001; Fig 3, left). Multivariate analysis with the Cox proportional hazards model demonstrated that only MP was a significant independent predictor for ipsilateral ischemic events. The relative risk conferred by MP was 83.1 (95% confidence interval, 6.8–1017.4; P < .001).

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative failure curves for ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with and without misery perfusion (left) or decreased CBF/CBV (right). The number of patients who remained event-free and available for follow-up evaluation during each 6-month interval is shown at the bottom of the graph.

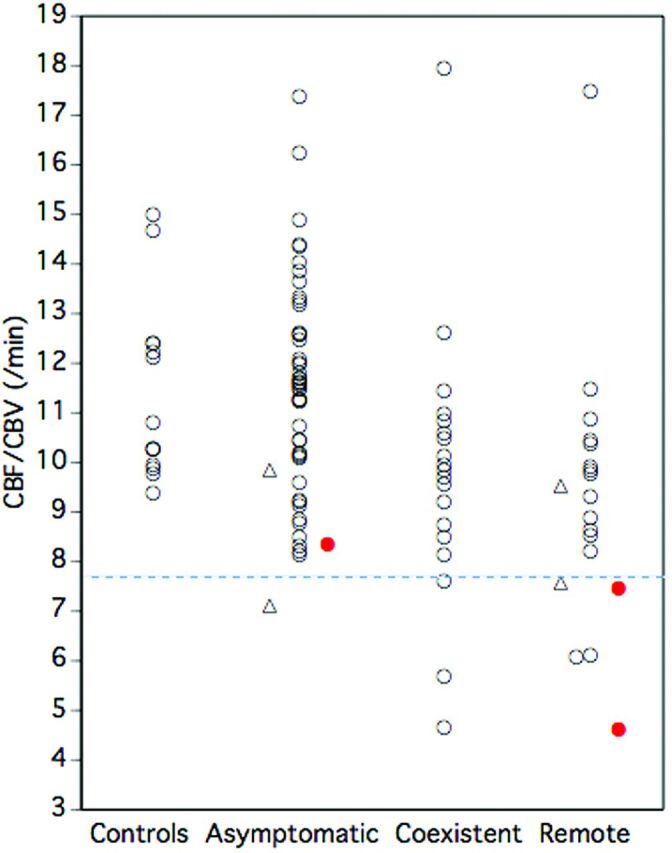

The ipsilateral ischemic event incidence in patients with decreased CBF/CBV (2/9) was significantly higher than that of patients without decreased CBF/CBV (1/80) (Fisher exact test; P = .026) (Fig 4), while no significant difference was found between that of patients with increased OEF (2/17) and patients without increased OEF (1/72) (Fisher exact test; P = .092). Kaplan-Meier analysis with censoring at the time of bypass surgery revealed that the incidence of ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with increased OEF or decreased CBF/CBV was significantly higher than that of patients without it (log-rank test; P < .05 and P = .0001, respectively) (Fig 3, right). When increased OEF or decreased CBF/CBV was used as a covariate instead of MP, multivariate analysis with the Cox proportional hazards model demonstrated that only decreased CBF/CBV was a significant independent predictor for ipsilateral ischemic events; increased OEF was not. The relative risk values conferred by decreased CBF/CBV and increased OEF were 24.8 (95% CI, 2.2–277.3; P < .01) and 9.8 (95% CI, 0.8–108.4; P = .063), respectively.

Fig 4.

Relationship between decreased CBF/CBV and ischemic events. Closed circles (red) indicate patients with ischemic events. A dashed line (blue) denotes the lower 95% limit defined in healthy controls. Triangles indicate patients who underwent bypass surgery.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that chronic hemodynamic compromise on 15O-PET is a predictor of subsequent ischemic events in the hemispheres with asymptomatic or remote (>6 months) symptomatic atherosclerotic intracranial disease of the ICA or MCA. The 2-year incidence of ipsilateral ischemic events in patients with MP (2/5) or decreased CBF/CBV (2/9) was significantly higher than that of patients without MP (1/84) or decreased CBF/CBV (1/80), respectively. Evaluation of chronic hemodynamic compromise may identify a subgroup of higher risk patients in asymptomatic or remote (>6 months) symptomatic LAICOD that has a low risk of ischemic events in general.4

No studies have investigated the relationship between chronic hemodynamic compromise on 15O-PET and asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD prognosis. Previous studies of symptomatic atherosclerotic large-artery disease, including LAICOD, suggested that patients with chronic hemodynamic compromise are at high risk for subsequent stroke.13–17 Thus, chronic hemodynamic compromise may also confer a higher risk of ischemic events in patients with asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD. The results of this study support this hypothesis, though only a few patients in this small sample experienced subsequent ischemic events. However, our findings are consistent with the benign prognosis of asymptomatic LAICOD reported by several studies.4,25–28 Correct evaluations of hemodynamic status by using 15O-PET could identify a small subgroup of higher risk patients among low-risk patients with LAICOD. MP was the best predictor of ischemic events, and decreased CBF/CBV also predicted ischemic events, though the predictive value of decreased CBF/CBV was lower than that of MP. The CBF/CBV is the reciprocal of the expression for vascular MTT, which can be evaluated by perfusion imaging with MR imaging or CT in routine clinical practice.29,30 The ability of perfusion MR imaging or CT methods to predict the risk of future ischemic events should be studied in a larger patient sample.6 In the future, the combination of perfusion imaging with oxygen imaging by using MR imaging, which may detect MP, would allow greater accuracy in identifying higher risk patients.31,32

In asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD, cerebral hemodynamics and metabolism have not been studied specifically. In this study, the degree of hemodynamic compromise at baseline was mild. However, cerebral atherosclerosis is a dynamic disease that can progress or regress.33 Thus, to improve long-term prognosis in patients with asymptomatic or remote (>6 months) symptomatic atherosclerotic LAICOD, preventing hemodynamic deterioration due to the progression of artery disease may be important. This could be achieved by appropriately managing atherogenic risk factors. In patients with carotid occlusion, asymptomatic hemodynamic deterioration has been demonstrated to cause subsequent hemodynamic stroke during long-term (>2 years) follow-up.34 Hemodynamic assessment at baseline may be useful to identify patients who require aggressive medical management. Furthermore, follow-up evaluation of hemodynamic status and cerebral atherosclerosis might identify patients whose stroke risk is increased in asymptomatic or remote symptomatic atherosclerotic LAICOD.

The major limitation of this study was that only a few ischemic events occurred in the small patient sample. Because our cohort comprised patients who were examined on a PET unit, our results are subject to referral or selection bias. Patients perceived to be at high risk for ischemic events might have been more readily referred for 15O-PET investigation. Despite the possibility of overestimation of ischemic-event risk, asymptomatic or remote symptomatic LAICOD had a low risk of ischemic events and a low incidence of MP, suggesting that benign prognosis may be associated with less hemodynamic impairment in these patients. Because only a few patients experienced subsequent ischemic events, we were unable to establish a conclusive relationship between hemodynamic compromise and ischemic event risk. Future MR imaging or CT studies by using MTT measurements should be performed in a large number of patients.

This study has other limitations. It is debatable whether TIAs without infarction are clinically important. However, the 90-day risk of ischemic stroke was reported to be 6.9% after TIA in patients with intracranial artery stenosis.35 Thus, detection of patients at high risk for TIA is meaningful for preventing subsequent stroke. Thirty-six percent of patients were diagnosed by MR angiography, which could have overestimated stenosis. The selection of bypass surgery was left to the individual clinical judgment of attending physicians, which may have caused selection bias. The lack of coregistered MR imaging to define the ROIs might have limited correct stratification of the patient groups. However, calculation of the mean hemispheric value by using ROIs placed compactly on multiple image sections could help to diminish this error. In some patients, hemodynamic compromise severity might not have been reflected by the 15O-PET variables in the whole hemisphere; they may have been more regional. The healthy control subjects were younger than the patients. With 15O-PET, in the cerebral cortical ROIs of the MCA distribution, CBF, CMRO2, and CBV were reported to decrease with age, while OEF and CBF/CBV did not change with age.36 Thus, the degree of hemodynamic compromise evaluated with OEF and CBF/CBV may not be affected by the inadequate matching for age.

Conclusions

In the hemispheres with asymptomatic or remote (>6 months) symptomatic atherosclerotic LAICOD, those with chronic hemodynamic compromise, specifically MP or decreased CBF/CBV, appear to be at high risk for cerebral ischemic events under standard medical therapy. This small subgroup of patients with higher risk LAICOD may need aggressive medical management and can be identified by detecting increased MTT by using perfusion MR imaging or CT imaging in routine clinical practice.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- CI

confidence interval

- CMRO2

cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen

- LAICOD

large-artery intracranial occlusive disease

- MP

misery perfusion

- OEF

oxygen extraction fraction

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (22613001, H.Y.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Gorelick PB, Wong KS, Bae HJ, et al. Large artery intracranial occlusive disease: a large worldwide burden but a relatively neglected frontier. Stroke 2008;39:2396–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1305–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chimowitz M, Lynn M, Derdeyn C, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:993–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RA, Kasner SE. Natural history of asymptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. J Neuroimaging 2009;19(suppl 1):17S–19S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasner SE, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation 2006;113:555–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fargen KM, Velat GJ, Lawson MF, et al. Flow failure from intracranial atherosclerotic disease: a rationale for endovascular intervention in a population with recurrent symptoms despite maximal medical therapy. J Neurointerv Surg 2013;5:e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebeskind DS, Cotsonis GA, Saver JL, et al. Collaterals dramatically alter stroke risk in intracranial atherosclerosis. Ann Neurol 2011;69:963–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powers WJ. Cerebral hemodynamics in ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Ann Neurol 1991;29:231–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Fujimoto N, et al. Significance of low perfusion with increased oxygen extraction fraction in a case of internal carotid artery stenosis. Stroke 1992;23:431–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazighi M, Tanasescu R, Ducrocq X, et al. Prospective study of symptomatic atherothrombotic intracranial stenoses: the GESICA study. Neurology 2006;66:1187–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron JC, Bousser MG, Rey A, et al. Reversal of focal “misery-perfusion syndrome” by extra-intracranial arterial bypass in hemodynamic cerebral ischemia: a case study with 15O positron emission tomography. Stroke 1981;12:454–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baron JC, Jones T. Oxygen metabolism, oxygen extraction and positron emission tomography: historical perspective and impact on basic and clinical neuroscience. Neuroimage 2012;61:492–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuroda S, Houkin K, Kamiyama H, et al. Long-term prognosis of medically treated patients with internal carotid or middle cerebral artery occlusion: can acetazolamide test predict it? Stroke 2001;32:2110–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogasawara K, Ogawa A, Yoshimoto T. Cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide and outcome in patients with symptomatic internal carotid or middle cerebral artery occlusion: a xenon-133 single-photon emission computed tomography study. Stroke 2002;33:1857–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, et al. Evidence of misery perfusion and risk for recurrent stroke in major cerebral arterial occlusive diseases from PET. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, et al. Significance of increased oxygen extraction fraction in 5-year prognosis of major cerebral arterial occlusive diseases. J Nucl Med 1999;40:1992–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamauchi H, Higashi T, Kagawa S, et al. Is misery perfusion still a predictor of stroke in symptomatic major cerebral artery disease? Brain 2012;135:2515–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, et al. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:643–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis: North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N Engl J Med 1991;325:445–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okazawa H, Yamauchi H, Sugimoto K, et al. Quantitative comparison of the bolus and steady-state methods for measurement of cerebral perfusion and oxygen metabolism: positron emission tomography study using 15O gas and water. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2001;21:793–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frackowiak RS, Lenzi GL, Jones T, et al. Quantitative measurement of regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism in man using 15O and positron emission tomography: theory, procedure, and normal values. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1980;4:727–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lammertsma AA, Jones T. Correction for the presence of intravascular oxygen-15 in the steady-state technique for measuring regional oxygen extraction ratio in the brain. 1. Description of the method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1983;3:416–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumann P, Touzani O, Young AR, et al. Evaluation of the ratio of cerebral blood flow to cerebral blood volume as an index of local cerebral perfusion pressure. Brain 1998;121(pt 7):1369–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Kimura J, et al. Hemodynamics in internal carotid artery occlusion examined by positron emission tomography. Stroke 1990;21:1400–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kern R, Steinke W, Daffertshofer M, et al. Stroke recurrences in patients with symptomatic vs asymptomatic middle cerebral artery disease. Neurology 2005;65:859–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kremer C, Schaettin T, Georgiadis D, et al. Prognosis of asymptomatic stenosis of the middle cerebral artery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1300–03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nahab F, Cotsonis G, Lynn M, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of coexistent asymptomatic intracranial stenosis. Stroke 2008;39:1039–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ni J, Yao M, Gao S, et al. Stroke risk and prognostic factors of asymptomatic middle cerebral artery atherosclerotic stenosis. J Neurol Sci 2011;301:63–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajimoto K, Moriwaki H, Yamada N, et al. Cerebral hemodynamic evaluation using perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with positron emission tomography values in chronic occlusive carotid disease. Stroke 2003;34:1662–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dani KA, Thomas RG, Chappell FM, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance perfusion imaging in ischemic stroke: definitions and thresholds. Ann Neurol 2011;70:384–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seiler A, Jurcoane A, Magerkurth J, et al. T2′ imaging within perfusion-restricted tissue in high-grade occlusive carotid disease. Stroke 2012;43:1831–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen-Kondering U, Baron JC. Oxygen imaging by MRI: can blood oxygen level-dependent imaging depict the ischemic penumbra? Stroke 2012;43:2264–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mok VC, Lam WW, Chen XY, et al. Statins for asymptomatic middle cerebral artery stenosis: the regression of cerebral artery stenosis study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamauchi H, Fukuyama H, Nagahama Y, et al. Long-term changes of hemodynamics and metabolism after carotid artery occlusion. Neurology 2000;54:2095–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ovbiagele B, Cruz-Flores S, Lynn MJ, et al. Early stroke risk after transient ischemic attack among individuals with symptomatic intracranial artery stenosis. Arch Neurol 2008;65:733–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain 1990;113:27–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]