Abstract

Outcomes of patients with primary refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are dismal. The role of autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (autoHCT) in this population is not well defined in the modern era. Most datasets combine these patients with those with relapsed disease. We report the outcomes of autoHCT in patients with primary refractory DLBCL that subsequently demonstrated chemosensitive disease with salvage therapies, using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) registry. Between 2003 and 2018, 169 patients met the inclusion criteria. The median age of the cohort was 54 years, 64% were male. The patients had advanced stage disease (73%) at diagnosis, 27% patients had stable disease and 73% had progressive disease after frontline chemoimmunotherapy. Following salvage therapy, 36% patients were in complete remission (CR) and 64% in partial remission (PR). Non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression/relapse, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of this cohort at 4-years was 10.8% (95%CI 6–13), 47.8% (95%CI 41–52), 41.4% (95%CI 38–50) and 49.6% (95 CI 44–56), respectively. On univariate analysis, patients with progressive disease after frontline chemoimmunotherapy did just as well as those with stable disease. Patients achieving CR with salvage therapy had a lower cumulative incidence of progression/relapse at one year (30% vs 46.9%; p=0.02) and experienced superior one-year PFS compared to patients in PR (63.2% vs 46.7%; p=0.03). AutoHCT provides durable disease control and should remain the standard-of-care in primary refractory DLBCL patients who respond to salvage therapies.

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, autologous transplantation, primary refractory

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histologic subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Anthracycline and rituximab-based combination frontline chemoimmunotherapy is highly active and will cure 50–60% of patients.1,2 Relapsed/refractory disease is treated with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) in patients with chemosensitive disease, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) modified T-cells in patients with refractory disease.3,4

Similar to other hematologic malignancies, response to therapy is prognostic in DLBCL. Patients achieving a complete response (CR) to frontline chemoimmunotherapy by clinical and radiologic criteria experience improved long-term survival.5 Patients with less than a CR, evidence of frank disease progression after completion of frontline therapy, or those who experience early disease relapse with short period of CR have been defined as early treatment/rituximab failure and have poor outcomes.6

Several studies to date have attempted to describe the outcomes of this group. In the pre-rituximab era, using data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), Vose et al. showed that autoHCT can salvage patients with primary refractory disease.7 A subsequent CIBMTR analysis showed that autoHCT can salvage patients with early chemoimmuotherapy failure.8 However, there are no studies specifically evaluating the outcomes of patients with DLBCL who experience stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) (called primary refractory disease for the purpose of this study) in response to rituximab containing frontline chemoimmunotherapy. The long-term survival of this subset of patients is particularly dismal.9,10 While many investigators also consider partial response (PR) to frontline therapy as primary refractory disease,11,12 we aimed to focus on the most refractory cases to critically appraise the value of autoHCT in this challenging population. Additionally, the limited efficacy of available post relapse salvage therapies renders a large proportion of patients with primary refractory disease ineligible for autoHCT.

The objective of our study is to report the outcomes of patients with primary refractory DLBCL herein defined as patients experiencing SD or PD in response to frontline chemoimmunotherapy, who subsequently respond to salvage therapy and undergo an autoHCT.

Methods

Data source

The CIBMTR is a collaborative research program managed by Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) and The National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) that collects data from more than 500-transplant centers worldwide. Participating sites are required to report detailed data on both autologous and allogeneic HCT with frequent updates gathered during the longitudinal follow-up of transplant patients and the compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. The MCW and NMDP institutional review boards approved this study.

Patients

Primary refractory DLBCL patients (aged ≥18 years), who received an auto-HCT between 2003 and 2018 and reported to CIBMTR were included in this analysis. Primary refractory disease was defined as either SD or PD as best response to rituximab and anthracycline-containing frontline chemoimmunotherapy. All patients in our study showed evidence of subsequent response to salvage chemotherapy (CR or PR) prior to auto-HCT. Patients who received a bone marrow graft, those with chemorefractory disease after salvage therapy, and those patients with active central nervous system involvement prior to auto-HCT were excluded.

Definitions and Endpoints:

Chemosensitive disease is defined as achieving either a CR or PR to salvage treatment prior to transplant. Response to frontline chemoimmunotherapy and disease status prior to auto-HCT were determined using the International Working Group criteria13,14.

Primary endpoint is overall survival (OS). The OS is defined as the interval from the date of transplantation to the date of death or last follow-up. Death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) is defined as death without evidence of lymphoma progression/relapse; relapse is considered a competing risk. Progression/relapse is defined as progressive lymphoma after autoHCT or lymphoma recurrence after a CR; NRM is considered a competing risk. For progression-free survival (PFS), a patient is considered a treatment failure at the time of progression/relapse or death from any cause. For relapse, NRM, and PFS patients alive without evidence of disease relapse or progression are censored at last follow-up. Neutrophil recovery is defined as the first of 3 successive days with absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 500/μL after post-transplantation nadir. Platelet recovery is considered to have occurred on the first of three consecutive days with platelet count 20,000/μL or higher, in the absence of platelet transfusion for 7 consecutive days. For neutrophil and platelet recovery, death without the event is considered a competing risk. All outcomes are calculated relative to the transplant date.

Statistical Analysis:

The distribution of OS and PFS are estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cumulative incidence method is used to estimate hematopoietic recovery, NRM, relapse/progression while accounting for competing events. Results are reported as 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value, with p value <0.05 considered statistically significant. Due to the small sample size of the study, only univariate analysis was conducted and regression modeling (e.g. proportional hazards model) was not performed. All statistical analyses are performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results:

One hundred and sixty nine adult patients with primary refractory DLBCL met the inclusion criteria for the study (baseline characteristics, Table 1). The median age of the cohort is 54 years (20–77 years) with 64% (n=109) males. Most patients were White (77%; n=130) and African Americans constituted 12% (n=21) of the cohort. Over half of the patients had excellent performance status (Karnofsky Performance Score, KPS ≥90, 51%). 123 (73%) patients had advanced stage (stage III-IV) disease at diagnosis. Among patients with baseline lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) available, one-thirds (33%) had elevated LDH. The median lines of therapy prior to autoHCT was 2 (range 1–5). The median time from diagnosis to autoHCT was 10.9 months (2.7–138.2 months). The majority of the patients had PD (n=124, 73%) and the remaining (n=45, 27%) had SD after frontline chemoimmunotherapy. Following salvage therapy, 35% (n=60) patients achieved CR and 65% (n=109) PR at the time of autoHCT. Conditioning regimens included BEAM (BCNU, etoposide, melphalan, and cytarabine, 85%; BEAM 77%, rituximab-BEAM 23%), busulfan/cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy) (10%), and CBV (cyclophosphamide, BCNU, and etoposide, 5%). Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) scan prior to conditioning was positive in 53% (n=90), negative in 23% (n=39), and not performed/not reported 24% (n=40) patients. In our present series, 41% autoHCT procedures were recorded after 2012.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with primary refractory DLBCL patients undergoing autologous HCT between 2003 and 2018.

| Patient age, years, median (range) | 54 (20–77) |

| ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 40 (24) |

| Male Gender, n (%) | 109 (64) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 130 (77) |

| African American | 21 (12) |

| Others | 9 (5) |

| Missing | 9 (5) |

| Karnofsky performance score ≥ 90, n (%) | 87 (51) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

| Stage III‐IV at diagnosis, n (%) | 123 (73) |

| Missing | 10 (6) |

| LDH elevated at diagnosis, n (%) | 22 (13) |

| Missing | 104 (62) |

| No. of lines of therapy prior to HCT, median (range) | 2 (1‐5) |

| No bone marrow involvement at diagnosis, n (%) | 131 (78) |

| Missing | 11 (7) |

| Extranodal involvement at diagnosis, n (%) | 90 (53) |

| Missing | 11 (7) |

| Time from diagnosis to HCT, mo, median (range) | 10.9 (2.7–138.2) |

| <3 months | 1 (1) |

| 3 to <6 months | 14 (8) |

| 6 to <12 months | 77 (45) |

| 12 to <24 months | 54 (32) |

| ≥24 months | 23 (14) |

| Remission status at autoHCT, n (%) | |

| Complete remission | 60 (36) |

| Partial remission | 109 (64) |

| Conditioning Regimen – No (%) | 143 (85) |

| BEAM | 17 (10) |

| Bu/Cy | 9 (5) |

| CBV | |

| PET CT scan result at last evaluation – No. (%) | |

| Positive | 90 (53) |

| Negative | 39 (23) |

| Not done/Not Reported | 40 (24) |

| Year of HCT – no. (%) | |

| 2004–2011 | 99 (59) |

| 2012–2018 | 70 (41) |

Abbreviations: BEAM indicates BCNU, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; CNS, central nervous system; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; autoHCT, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

Transplantation outcomes

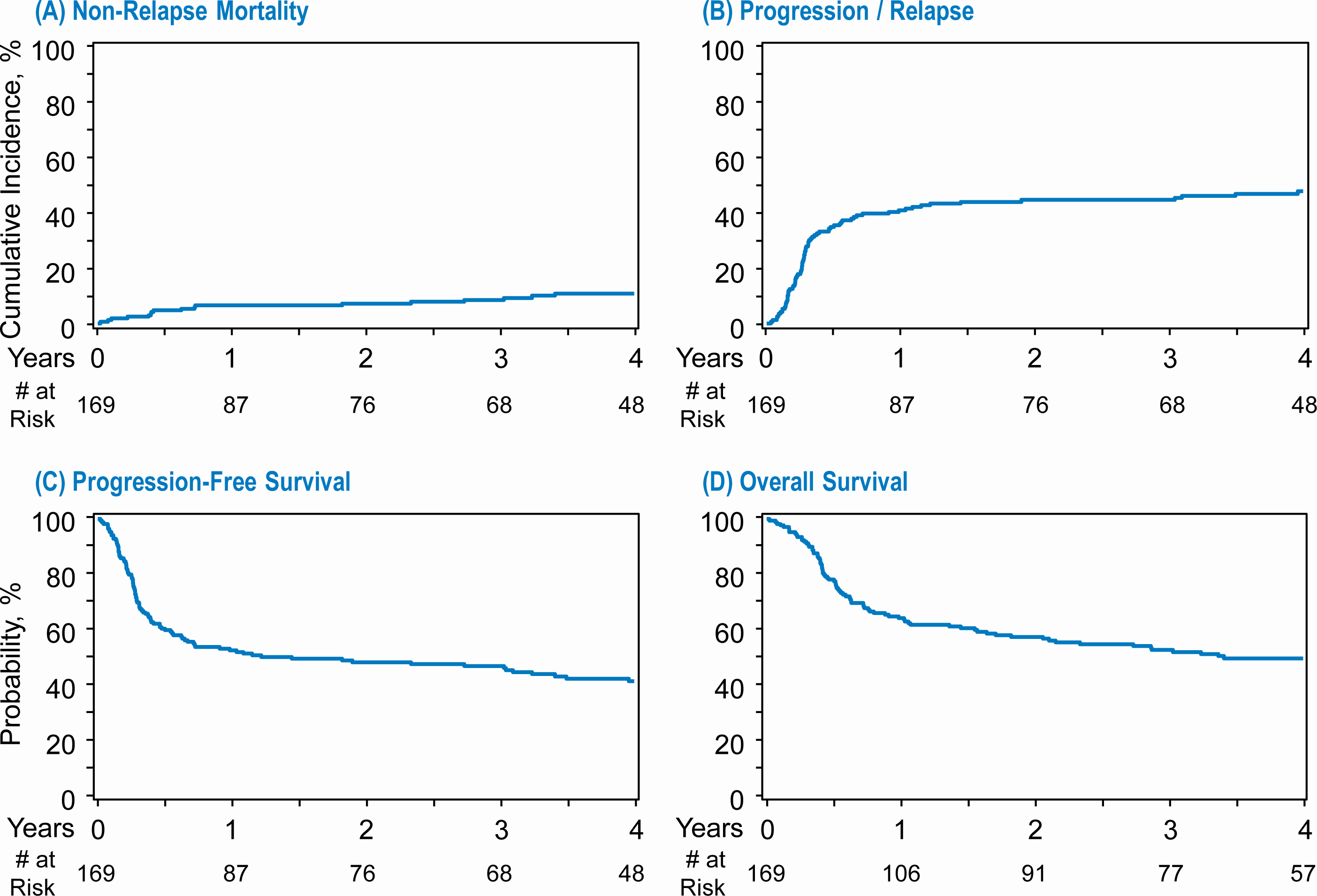

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at day 30 was 98.2% (95%CI=95.3–99.7%) and platelet recovery at day 100 was 97% (95%CI=93.5–99.1%) (Table 2). The 1-year cumulative incidence of NRM was 6.5% (95%CI=3.3–10.8%) (Table 2, Figure 1A). The 4-year cumulative incidence of relapse/progression was 47.8% (95%CI= 40.1–55.5%) (Table 2). The 4-year PFS was 41.4% (95%CI=33.8–49.2%) (Table 2). The 4-year OS was 49.6% (95%CI=41.9–57.4%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate outcomes for primary refractory DLBCL patients undergoing autologous HCT.

| (N = 169) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N | Prob (95% CI) |

| Neutrophil engraftment | 165 | |

| 28-day | 98.2 (95.3–99.7)% | |

| Platelet recovery | 164 | |

| 100-day | 97 (93.5–99.1)% | |

| NRM | 169 | |

| 1-year | 6.5 (3.3–10.8)% | |

| 2-year | 7.1 (3.7–11.5)% | |

| 3-year | 8.5 (4.7–13.3)% | |

| 4-year | 10.8 (6.4–16.2)% | |

| Progression/relapse | 169 | |

| 1-year | 40.9 (33.6–48.4)% | |

| 2-year | 44.6 (37.2–52.2)% | |

| 3-year | 44.6 (37.2–52.2)% | |

| 4-year | 47.8 (40.1–55.5)% | |

| Progression-free survival | 169 | |

| 1-year | 52.6 (45–60)% | |

| 2-year | 48.2 (40.7–55.8)% | |

| 3-year | 46.8 (39.3–54.5)% | |

| 4-year | 41.4 (33.8–49.2)% | |

| Overall survival | 169 | |

| 1-year | 64.2 (56.8–71.3)% | |

| 2-year | 57.4 (49.8–64.8)% | |

| 3-year | 52.7 (45–60.3)% | |

| 4-year | 49.6 (41.9–57.4)% | |

Figure 1:

Transplant outcomes for primary refractory DLBCL. (A) Non relapse mortality (B) Progression/relapse (C) Progression free survival (D) Overall survival

Impact of response to frontline chemoimmunotherapy

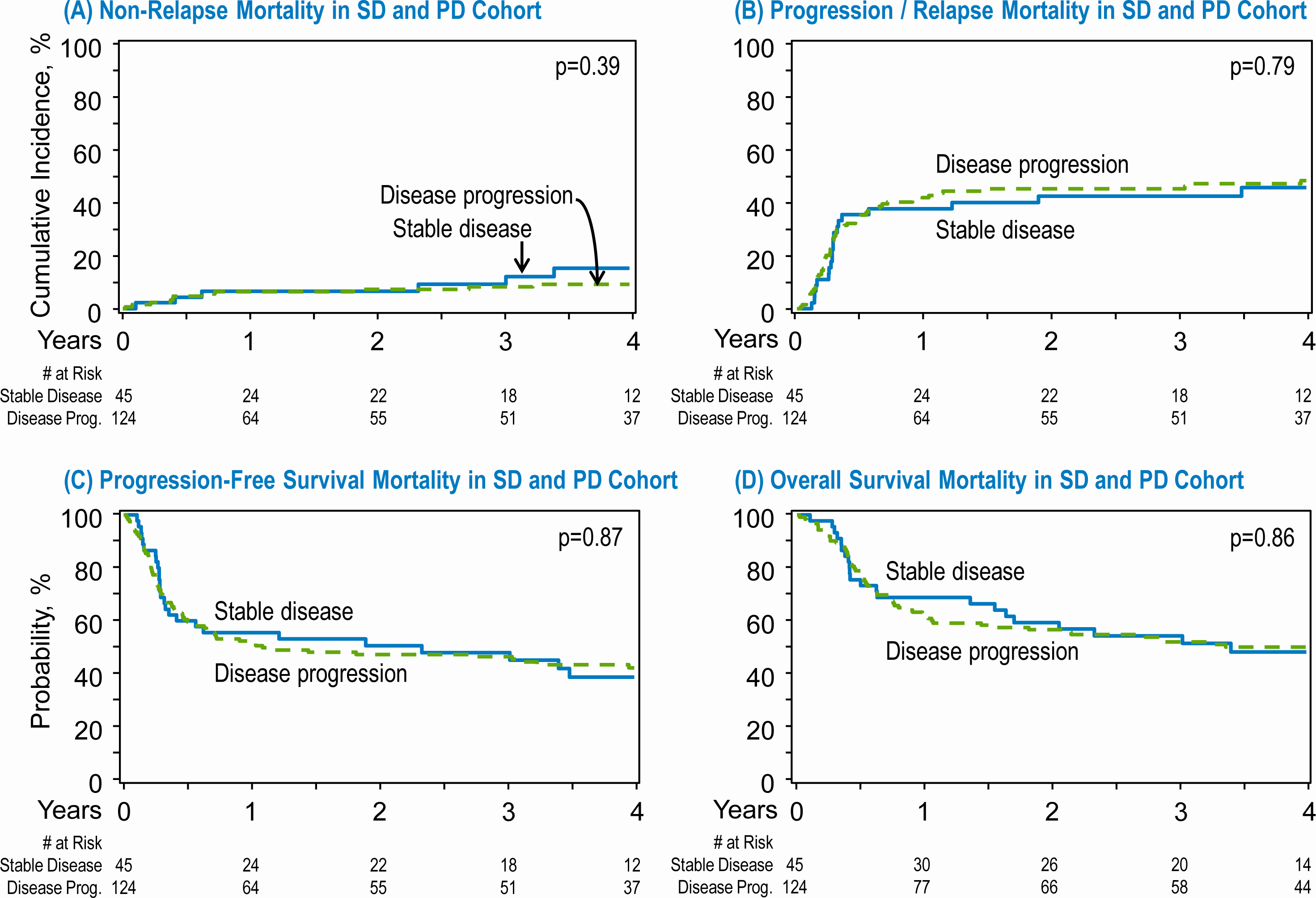

Among the 169 patients included in our study, the majority had PD (N=124; 73%) and the remaining had SD (N=45; 27%) after completion of frontline chemoimmunotherapy. A subgroup univariate analysis of patients by response status did not show any differences in the NRM (1-year NRM, SD 6.7% vs PD 6.5%, p=0.96), progression/relapse (1-year SD 37.8% vs. PD 42%, p=0.6; 4-year SD 45.8% vs. PD 48.5%, p=0.7), PFS or OS did not differ significantly at any time points between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate outcomes for primary refractory DLBCL patients undergoing autologous HCT, comparing stable disease vs. progressive disease in response to first line of therapy

| Stable disease (N = 45) | Progressive disease (N = 124) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N | Prob (95% CI) | N | Prob (95% CI) | P Value |

| NRM | 45 | 124 | 0.387 | ||

| 1-year | 6.7 (1.3–15.9)% | 6.5 (2.8–11.5)% | 0.965 | ||

| 2-year | 6.7 (1.3–15.9)% | 7.3 (3.4–12.6)% | 0.886 | ||

| 3-year | 9.3 (2.4–20.0)% | 8.2 (4.0–13.8)% | 0.832 | ||

| 4-year | 15.4 (5.7–28.8)% | 9.3 (4.7–15.2)% | 0.352 | ||

| Progression/relapse | 45 | 124 | 0.789 | ||

| 1-year | 37.8 (24.1–52.5)% | 42.0 (33.4–50.9)% | 0.621 | ||

| 2-year | 42.6 (28.4–57.5)% | 45.3 (36.6–54.2)% | 0.756 | ||

| 3-year | 42.6 (28.4–57.5)% | 45.3 (36.6–54.2)% | 0.756 | ||

| 4-year | 45.8 (30.9–61.2)% | 48.5 (39.5–57.5)% | 0.774 | ||

| Progression-free survival | 45 | 124 | 0.875 | ||

| 1-year | 55.6 (41.0–69.6)% | 51.5 (42.7–60.2)% | 0.640 | ||

| 2-year | 50.7 (36.2–65.2)% | 47.3 (38.6–56.2)% | 0.700 | ||

| 3-year | 48.1 (33.5–62.8)% | 46.4 (37.7–55.3)% | 0.853 | ||

| 4-year | 38.8 (24.3–54.3)% | 42.3 (33.5–51.3)% | 0.697 | ||

| Overall survival | 45 | 124 | 0.857 | ||

| 1-year | 68.9 (54.8–81.4)% | 62.5 (53.8–70.8)% | 0.433 | ||

| 2-year | 59.4 (44.7–73.3)% | 56.7 (47.8–65.3)% | 0.752 | ||

| 3-year | 54.3 (39.5–68.8)% | 52.1 (43.2–61.0)% | 0.803 | ||

| 4-year | 48.2 (33.1–63.5)% | 50.0 (41.1–59.0)% | 0.844 | ||

Impact of Remission Status prior to autoHCT

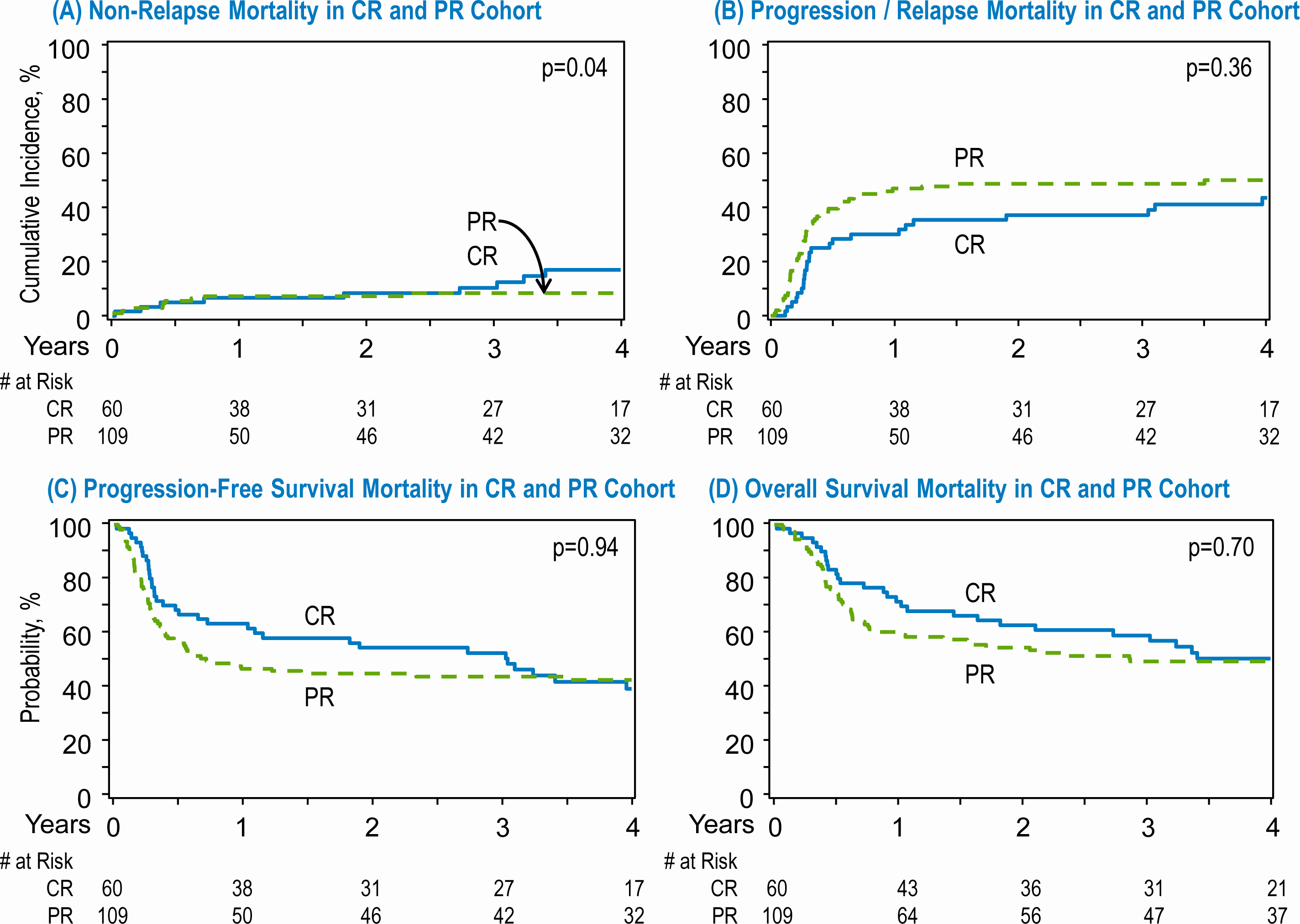

A higher proportion of patients were noted to be in a PR at the time of auto-HCT compared to CR (PR N=109, 65% vs CR N=60, 35%, Table 4). A subgroup univariate analysis of patients by response status did not show any differences in the 1-year cumulative incidence of NRM in the CR 6.7% versus PR groups 6.4% groups (p=0.94; Table 4). At 1-year, there was a lower incidence of relapse/progression in the CR group (30%) compared to the PR group (47%) (p=0.029) which translated into a higher PFS at 1-year in the CR group 63% compared to 47% in PR group (p=0.03). However, this difference was not noted beyond the first year. The 4-year PFS was 39% for the CR group versus 43% in the PR group (p=0.69)

Table 4.

Univariate outcomes for primary refractory DLBCL patients undergoing autologous HCT based on complete response (CR) or partial response (CR) to salvage therapy.

| CR (N = 60) | PR (N = 109) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | N | Prob (95% CI) | N | Prob (95% CI) | P Value |

| Neutrophil engraftment | 59 | 106 | 0.690 | ||

| 28-day | 98.3 (90.5–100)% | 98.1 (94.1–99.9)% | 0.946 | ||

| Platelet recovery | 58 | 106 | 0.371 | ||

| 100-day | 98.3 (90.4–100)% | 96.2 (91.4–99.1)% | 0.516 | ||

| NRM | 60 | 109 | 0.038 | ||

| 1-year | 6.7 (1.8–14.5)% | 6.4 (2.6–11.8)% | 0.943 | ||

| 2-year | 8.5 (2.7–17.0)% | 6.4 (2.6–11.8)% | 0.639 | ||

| 3-year | 10.5 (3.9–19.8)% | 7.5 (3.2–13.2)% | 0.534 | ||

| 4-year | 17.1 (8.0–28.8)% | 7.5 (3.2–13.2)% | 0.103 | ||

| Progression/relapse | 60 | 109 | 0.357 | ||

| 1-year | 30.0 (19.1–42.3)% | 46.9 (37.5–56.3)% | 0.029 | ||

| 2-year | 37.1 (25.2–49.8)% | 48.8 (39.4–58.2)% | 0.143 | ||

| 3-year | 37.1 (25.2–49.8)% | 48.8 (39.4–58.2)% | 0.143 | ||

| 4-year | 43.6 (30.7–56.9)% | 50.0 (40.5–59.5)% | 0.439 | ||

| Progression-free survival | 60 | 109 | 0.942 | ||

| 1-year | 63.2 (50.7–74.9)% | 46.7 (37.5–56.1)% | 0.035 | ||

| 2-year | 54.5 (41.7–66.9)% | 44.8 (35.6–54.2)% | 0.231 | ||

| 3-year | 52.4 (39.7–65.1)% | 43.8 (34.6–53.2)% | 0.285 | ||

| 4-year | 39.3 (26.5–52.8)% | 42.5 (33.3–52.0)% | 0.699 | ||

| Overall survival | 60 | 109 | 0.697 | ||

| 1-year | 71.5 (59.4–82.1)% | 60.3 (50.9–69.2)% | 0.136 | ||

| 2-year | 62.7 (50.1–74.6)% | 54.5 (45.1–63.8)% | 0.299 | ||

| 3-year | 58.9 (46.1–71.2)% | 49.3 (39.8–58.8)% | 0.235 | ||

| 4-year | 50.4 (37.2–63.6)% | 49.3 (39.8–58.8)% | 0.896 | ||

The OS was numerically higher in the CR group at one year 72% vs 60% in the PR group, although it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1). At 4 years, OS is comparable at 50% in the CR vs 49% in the PR groups respectively (P=0.8, Table 4). The small number of patients again precludes multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Optimal management of patients with primary refractory DLBCL patients in the rituximab era is unclear. To date, published prospective randomized studies exclusively evaluating the outcomes of this population are lacking. Most retrospective reports have significant inconsistencies in the definition of refractory disease, and often include patients with relapsed disease introducing heterogeneity. Our study suggests that patients with both SD and PD after frontline chemoimmunotherapy can experience durable disease control with autoHCT if they are eligible and respond to salvage therapy. While the depth of response prior to autoHCT remains predictive of relapse in the first year after transplant, a sizeable proportion of patients achieving at least a PR can experience durable remission with high dose therapy. At the onset, it also important to acknowledge the limitation that our analysis is applicable to only a very select cohort of primary refractory DLBCL patients, who were able to achieve chemosensitivity following salvage therapies.

Response to frontline chemoimmunotherapy is an established prognostic marker for both PFS and OS in DLBCL. Vardhana et al. reported outcomes of primary refractory DLBCL from a single institution.9 Fifty four patients with primary progressive disease (PP, minimal or no response to initial therapy) were included in the analysis. Twenty-seven (50%) patients showed sensitivity to salvage therapy [CR=8 (15%); PR=19 (35%)]. Sixteen (30%) patients with PP disease underwent autoHCT [CR=3 (19); PR=11 (69%)]. Unfortunately, the outcomes of the PP cohort undergoing transplant was not reported separately likely due to small numbers and remains a data-free zone. In the multicenter retrospective REFINE study, Costa et al. examined the primary progressive cohort (PP, N=144)10. Forty nine of the 144 patients proceeded with autoHCT. Two-year PFS and OS for auto-HCT patients were 38.4% (95% C.I. 29.6%−47.2%) and 54.9% (95% C.I. 44.9%−64.9%), respectively. Presence of two out of three factors (primary progressive disease, MYC status and intermediate-high/high risk national comprehensive cancer network/international prognostic index NCCN/IPI score) as ultra-high risk features predictive of inferior survival following autoHCT. In their study, disease response at time of transplant did not reach statistical significance as a predictor of OS. Our cohort of 169 patients examines the outcomes of this specific subset of patients and will serve a benchmark for reference for future studies.

Current salvage therapy options in patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL leave a lot to be desired. Responses rates are generally low (ORR<50%) among patients who experience early rituximab failure.4,15 Conversely, several studies have identified response to salvage therapy as the single most important prognostic factor for long-term survival among relapsed/refractory DLBCL.16,17 However, among studies limited to PP/refractory disease have conflicting results.9,10 In our present analysis, patients achieving CR with salvage therapy had a lower incidence of progression/relapse at one year (CR 30% vs. PR 46.9%; p=0.02) and improved one year PFS compared to patients in PR (CR 63.2% vs. PR 46.7%; p=0.03). Consistent with a previous report from CIBMTR, there were few progression events beyond the first year post autoHCT.8 Moving forward, the subset of patients in PR following salvage therapy could be considered for potential peri-autoHCT interventions to lower their risk of relapse.

We recognize several limitations of our registry-based study including its retrospective nature, lack of several pertinent variables including IPI score, c-myc gene status, cell of origin, exact number for frontline therapy cycles administered (before declaring a patient refractory), and a relatively smaller number of patients, all of which preclude multivariate analysis. Additionally, while the median time from diagnosis to transplant is 10.9 months, a proportion of patients underwent transplant >12 months from diagnosis. This captures patients with inherently good disease biology who are not only fit, but also survive long enough to receive multiple lines of therapy prior to autoHCT and proceed with autoHCT without interim disease progression.

Most importantly, as already acknowledged, this study does not evaluate outcomes of all primary refractory patients. The objective response rate to salvage therapy in the SCHOLAR-1 study for patients with primary refractory disease was 20% (CR 3%) and outcomes of patients who either do not respond or are not candidates for autoHCT remain dismal.18 Our study findings are generalizable to only a small subset of patients with primary refractory disease who subsequently demonstrate chemosensivity to salvage therapy and are candidates for consolidation with autoHCT.

In recent years, chimeric antigen receptor T (CART) cells have emerged as a potentially curative option for relapsed/refractory DLBCL.19,20 Two products (axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel) are currently FDA approved for use in patients refractory to two or more lines of therapy or progression after prior autoHCT. Several ongoing randomized studies (ZUMA-7, NCT03391466; TRANSCEND, NCT02631044; BELINDA, NCT03570892) are comparing CART cells to autoHCT in patients with relapsed disease prior to establishment of chemosensitivity to evaluate the best consolidative approach in this setting and may have important implications in the management of refractory patients in the near future.

In this CIBMTR study in patients with primary refractory DLBCL after modern frontline chemoimmunotherapy, autoHCT results in durable response and disease control in a proportion of patients who demonstrate subsequent chemosensitivity to salvage therapy. Based on our results, autoHCT should remain the standard-of-care in this population.

Figure 2:

Transplant outcomes in patients with stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) after frontline chemoimmunotherapy. (A) Non relapse mortality in SD and PD cohort. (B) Progression/relapse in the SD and PD cohort. (C) Progression free survival in the SD and PD cohort. (D) Overall survival in the in the SD and PD cohort.

Figure 3:

Transplant outcomes in patients with complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) after salvage therapy. (A) Non relapse mortality in CR and PR cohort. (B) Progression/relapse in the CR and PR cohort. (C) Progression free survival in the CR and PR cohort. (D) Overall survival in the in the CR and PR cohort.

Highlights.

Patients with primary refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who subsequently respond to salvage therapy can experience durable disease control with autologous stem cell transplantation (AutoHCT).

Benefit of autoHCT is seen in both patients who experience stable disease and progressive disease after frontline chemoimmunotherapy.

CIBMTR Support List

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service grant/cooperative agreement U24CA076518 with the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); grant/cooperative agreement U24HL138660 with NHLBI and NCI; grant U24CA233032 from the NCI; grants OT3HL147741, R21HL140314 and U01HL128568 from the NHLBI; contract HHSH250201700006C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); grants N00014-18-1-2888 and N00014-17-1-2850 from the Office of Naval Research; subaward from prime contract award SC1MC31881-01-00 with HRSA; subawards from prime grant awards R01HL131731 and R01HL126589 from NHLBI; subawards from prime grant awards 5P01CA111412, 5R01HL129472, R01CA152108, 1R01HL131731, 1U01AI126612 and 1R01CA231141 from the NIH; and commercial funds from Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Anthem, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; BARDA; Be the Match Foundation; bluebird bio, Inc.; Boston Children’s Hospital; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; Celgene Corp.; Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles; Chimerix, Inc.; City of Hope Medical Center; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; Dana Farber Cancer Institute; Enterprise Science and Computing, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); HistoGenetics, Inc.; Immucor; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; Japan Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Data Center; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karius, Inc.; Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc.; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin; Magenta Therapeutics; Mayo Clinic and Foundation Rochester; Medac GmbH; Mediware; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; Merck & Company, Inc.; Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Mundipharma EDO; National Marrow Donor Program; Novartis Oncology; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Oncoimmune, Inc.; OptumHealth; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; PCORI; Pfizer, Inc.; Phamacyclics, LLC; PIRCHE AG; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; REGiMMUNE Corp.; Sanofi Genzyme; Seattle Genetics; Shire; Sobi, Inc.; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; The Medical College of Wisconsin; University of Minnesota; University of Pittsburgh; University of Texas-MD Anderson; University of Wisconsin - Madison; Viracor Eurofins and Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Luciano Costa reports Research Support/Funding:Amgen; Celgene; Janssen. Consultancy: Amgen; GSK; Celgene; Karyopharm; Sanofi; Abbvie. Honoraria: Amgen; GSK; Celgene; Sanofi. Speaker’s Bureau: Amgen; Sanofi; Janssen. Advisor: Fujimoto Pharmaceutical Corporation Japan

Craig Sauter reports Research Support/Funding: Juno Therapeutics/Celgene/BMS, Precision Biosciences and Sanofi-Genzyme. Consultancy/Advisory board: Juno Therapeutics/Celgene/BMS, Sanofi-Genzyme, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Precision Biosciences, Kite—a Gilead Company and GSK. Research funds for investigator-initiated trials from: Juno Therapeutics and Sanofi-Genzyme.

Mehdi Hamadani reports Research Support/Funding: Spectrum Pharmaceuticals; Astellas Pharma. Consultancy: MedImmune LLC; Janssen R &D; Incyte Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Celgene Corporation; Pharmacyclics, Verastem. Speaker’s Bureau: Sanofi Genzyme, AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

All others do not/have not reported any conflicts.

References

- 1.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP Chemotherapy plus Rituximab Compared with CHOP Alone in Elderly Patients with Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Österborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. The Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(5):379–391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous Bone Marrow Transplantation as Compared with Salvage Chemotherapy in Relapses of Chemotherapy-Sensitive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage Regimens With Autologous Transplantation for Relapsed Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Rituximab Era. JCO. 2010;28(27):4184–4190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12(11):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70235-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisselbrecht C Is there any role for transplantation in the rituximab era for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma? Hematology. 2012;2012(1):410–416. doi: 10.1182/asheducation.V2012.1.410.3798518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vose JM, Zhang M-J, Rowlings PA, et al. Autologous Transplantation for Diffuse Aggressive Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in Patients Never Achieving Remission: A Report from the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry. JCO. 2001;19(2):406–413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamadani M, Hari PN, Zhang Y, et al. Early Failure of Frontline Rituximab-Containing Chemo-immunotherapy in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Does Not Predict Futility of Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014;20(11):1729–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardhana SA, Sauter CS, Matasar MJ, et al. Outcomes of primary refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) treated with salvage chemotherapy and intention to transplant in the rituximab era. Br J Haematol. 2017;176(4):591–599. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LJ, Maddocks K, Epperla N, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with primary treatment failure: Ultra-high risk features and benchmarking for experimental therapies. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(2):e24615. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills W, Chopra R, McMillan A, Pearce R, Linch DC, Goldstone AH. BEAM chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation for patients with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(3):588–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villela L, López-Guillermo A, Montoto S, et al. Prognostic features and outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who do not achieve a complete response to first-line regimens. Cancer. 2001;91(8):1557–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised Response Criteria for Malignant Lymphoma. JCO. 2007;25(5):579–586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification. JCO. 2014;32(27):3059–3067. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crump M, Kuruvilla J, Couban S, et al. Randomized Comparison of Gemcitabine, Dexamethasone, and Cisplatin Versus Dexamethasone, Cytarabine, and Cisplatin Chemotherapy Before Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed and Refractory Aggressive Lymphomas: NCIC-CTG LY.12. JCO. 2014;32(31):3490–3496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.9593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armand P, Welch S, Kim HT, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation in the positron emission tomography era. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(5):608–617. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauter CS, Matasar MJ, Meikle J, et al. Prognostic value of FDG-PET prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(16):2579–2581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-606939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130(16):1800–1808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Adult Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):45–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]