Abstract

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that do not code for proteins. LncRNAs play crucial regulatory roles in several biological processes via diverse mechanisms and their aberrant expression is associated with various diseases. LncRNA genes are further subcategorized based on their relative organization in the genome. MicroRNA (miRNA)-host-gene-derived lncRNAs (lnc-MIRHGs) refer to lncRNAs whose genes also harbor miRNAs. There exists crosstalk between the processing of lnc-MIRHGs and the biogenesis of the encoded miRNAs. Although the functions of the encoded miRNAs are usually well understood, whether those lnc-MIRHGs play independent functions are not fully elucidated. Here, we review our current understanding of lnc-MIRHGs, including their biogenesis, function, and mechanism of action, with a focus on discussing the miRNA-independent functions of lnc-MIRHGs, including their involvement in cancer. Our current understanding of lnc-MIRHGs strongly indicates that this class of lncRNAs could play important roles in basic cellular events as well as in diseases.

Keywords: cancer, long noncoding RNA, microprocessor, microRNA, splice site-overlapping miRNA

1 |. INTRODUCTION

1.1 |. Introduction of long noncoding RNA

The fraction of noncoding (nc) regions in the genome increases over the course of evolution. In humans, ~98% of the genome produces nc transcripts, which include small ncRNAs (20–50 nt), mid-size ncRNAs (50–200 nt) (Boivin, Faucher-Giguere, Scott, & Abou-Elela, 2019), and long nc RNAs (lncRNAs) (>200 nt). Most lncRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II and contain normal 5′-caps and 3′ poly-A tails (Marchese, Raimondi, & Huarte, 2017). The expression of lncRNAs is less conserved compared to mRNA genes. In addition, lncRNAs display cell line-, tissue-, or development-specific expression (Cabili et al., 2011; Ulitsky, 2016).

The annotation of lncRNAs is increasing at a rapid rate due to the advances in sequencing and computational technologies. Different databases use independent analyses or curation methods to annotate novel lncRNAs and make huge contributions to our understanding of the lncRNA repertoire. For instance, the GENCODE database uses RNA Capture Long Seq method to accurately annotate lncRNAs (Lagarde et al., 2017). Both LNCipedia and NONCODE databases integrate data from different individual resources. The number of lncRNA genes/transcripts reported in several major databases with the latest releases are summarized in Table 1. It is important to note that genes that are categorized as other types in these databases could also be lncRNAs. For example, GENCODE release 33 has reported 14,768 pseudogenes from which lncRNAs could be derived (Milligan & Lipovich, 2014).

TABLE 1.

Number of human long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in the latest releases of different databases

| Database | IncRNA gene | lncRNA transcript | Version |

|---|---|---|---|

| GENCODE (Frankish et al., 2019) | 17,952 genes | 48,438 | Release 33 (GRCh38.p13) |

| NCBI Refseq (O’Leary et al., 2016) | – | 27,381 | Release 109. 20200228 |

| LNCipedia (Volders et al., 2019) | 56,946 | 127,802 | Version 5 |

| NONCODE (S. Fang et al., 2018) | 96,308 | 172,216 | v5.0 |

Based on mechanistic studies of a small group of lncRNAs, we have learned that human lncRNAs play crucial roles in multiple biological events, including cell cycle, development, immune response, apoptosis, and disease development (Y. G. Chen, Satpathy, & Chang, 2017; Y. Fang & Fullwood, 2016; Flynn & Chang, 2014; Huarte, 2015; Kitagawa, Kitagawa, Kotake, Niida, & Ohhata, 2013; J. Li, Tian, Yang, & Gong, 2016; Schmitt & Chang, 2016). LncRNAs regulate molecular processes in nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments via various types of molecular mechanisms. In general, nuclear lncRNAs play either cis-acting or trans-acting functions to modulate chromatin, regulate gene transcription or processing, and/or organize nuclear structures (Q. Sun, Hao, & Prasanth, 2018). Cytoplasmic lncRNAs are known to regulate RNA stability, protein translation, and signal transduction (Noh, Kim, McClusky, Abdelmohsen, & Gorospe, 2018). Mechanistically, lncRNAs can behave as scaffolds for proteins, serve as microRNA (miRNA) sponges, interact with other RNA molecules, or bind to DNA elements such as enhancer elements (Y. Li, Syed, & Sugiyama, 2016; Marchese et al., 2017; Noh et al., 2018; Q. Sun, Hao, et al., 2018; K. C. Wang & Chang, 2011).

1.2 |. Introduction to miRNA

miRNAs (or miRs) were initially discovered back in 1993, by Lee and colleagues, in Caenorhabditis elegans (Lee, Feinbaum, & Ambros, 1993; Wightman, Ha, & Ruvkun, 1993) and later found to exist in many species, including mammals, plants, and even viruses. They are short nc RNAs that are ~22 nt long and regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. As reported by miRbase database release 22, the human genome contains 1917 miRNA genes (1917 annotated hairpin precursors and 2654 mature miRNA sequences) (Kozomara, Birgaoanu, & Griffiths-Jones, 2019). Mean-while, GENCODE database (release 33) reported 1881 miRNA genes (Frankish et al., 2019). Most miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA Polymerase II (Pol II). Similar to other mRNA genes, the expression of miRNAs is specifically regulated based on cell type, development stage, or disease situation (Ha & Kim, 2014). The aberrant expression levels/copy numbers of miRNAs and mutations in miRNAs are commonly associated with genetic diseases, including cancer (Baumann & Winkler, 2014; Czubak et al., 2015). Hence, miRNAs are used as diagnosis or prognosis markers for various diseases. Several miRNA-based treatment strategies have already been used in clinical applications (Baumann & Winkler, 2014; Farazi, Spitzer, Morozov, & Tuschl, 2011; Reddy, 2015).

miRNA–mRNA interaction results in post-transcriptional regulation of the target mRNAs, most commonly by inhibiting mRNA translation or regulating mRNA stability (Bartel, 2009; Gebert & MacRae, 2019; Treiber, Treiber, & Meister, 2019). The inhibition of translation is mediated by the release of eukaryotic initiation factor proteins from the target mRNA. miRNAs can also cause mRNA degradation by triggering poly-A shortening, followed by decapping of the target mRNAs (Gebert & MacRae, 2019). miRNAs play a huge role in regulating biological processes, including cell cycle, differentiation, development, immune response, and diseases (Bushati & Cohen, 2007; N. Li, Long, Han, Yuan, & Wang, 2017; Mehta & Baltimore, 2016; Saliminejad, Khorram Khorshid, Soleymani Fard, & Ghaffari, 2019). More than 60% of protein-coding genes in humans contain one or more miRNA target sites (Friedman, Farh, Burge, & Bartel, 2009). In addition, a single miRNA may target several mRNAs, and one mRNA can be targeted by different miRNAs.

2 |. LNC-MIRHGS FORM AN IMPORTANT BUT UNDER-STUDIED CLASS OF LncRNAs

miRNAs are initially transcribed from the genome as primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), which have a unique structure. A pri-miRNA contains a terminal loop, stem (including upper stem and lower stem), and single-stranded overhangs on both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the stem (Ha & Kim, 2014; Treiber et al., 2019). To exert the gene silencing function, miRNA need to be processed from pri-miRNA by several discrete steps, following the canonical or non-canonical miRNA biogenesis pathways.

2.1 |. Canonical miRNA biogenesis

Canonical miRNA biogenesis includes three major steps. The first step to generate precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) from pri-miRNA occurs in the nucleus, executed by the microprocessor complex: Drosha/DGCR8 (Gregory et al., 2004). The pri-miRNA is recognized by the microprocessor complex, consisting of DGCR8 dimer and Drosha (Nguyen et al., 2015). DGCR8 (DiGeorge critical region 8) is a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding protein that binds to pri-miRNA as a dimer. Drosha is an RNase III enzyme that cleaves the dsRNA between the upper stem and lower stem, which releases the hairpin-structured pre-miRNA. On the pri-mRNA, the basal junction refers to the junction between the lower stem and the flanking single-stranded RNA segments. The apical junction refers to the junction between the terminal loop and the upper stem. The distance from the Drosha cleavage site to the basal junction is ~11 nt, whereas the distance from the Drosha cleavage site to the apical junction is ~22 nt (Nguyen et al., 2015). The cleavage site of the microprocessor complex is precisely controlled by the structure of the microprocessor protein complex and the sequence elements of pri-miRNA. In particular, several motifs including the CNNC motif and UG motif in the basal junction and the UGUG motif in the terminal loop are important for pri-miRNA processing (Auyeung, Ulitsky, McGeary, & Bartel, 2013). In addition, both the basal junction and the apical junction play essential roles in the determination of the cleavage sites (Auyeung et al., 2013; Han et al., 2006; Kwon et al., 2019; Ma, Wu, Choi, & Wu, 2013; Zeng, Yi, & Cullen, 2005). Pre-miRNAs are transported to the cytoplasm by Exportin 5 (Exp5) and further cleaved by the RNase III enzyme Dicer (Song & Rossi, 2017). Dicer cuts on the dsRNA region near the terminal loop of pre-miRNAs to liberate a double stranded miRNA with a length of ~21 nt (Ha & Kim, 2014; MacRae, Zhou, & Doudna, 2007; Park et al., 2011).

Finally, the double-stranded miRNA, along with Argonaute (AGO) and associated factors, forms the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Filipowicz, Jaskiewicz, Kolb, & Pillai, 2005). The double-stranded miRNA is loaded on the AGO to form the pre-RISC, followed by the unwinding of the duplex. Only one strand from the miRNA duplex, called “guide strand”, stays with AGO in the mature RISC while the other strand is degraded. The 2nd nt to the ~7th or 8th nt of the guide strand is referred to as the seed sequence. The seed sequence will lead the RISC to form complementarity with their target mRNAs, usually at their 3′-UTR regions (Bartel, 2009; Gebert & MacRae, 2019). Although the miRNA duplex is able to generate guide miRNAs from both strands, one particular strand serves as the guide miRNA in most cases. Such selection preference is caused by the thermodynamic stability of the two ends: the strand with a less stable 5′ is favored as the guide miRNA (Schwarz et al., 2003).

2.2 |. Noncanonical miRNA biogenesis

Instead of the canonical pathway using microprocessors and Dicer, alternative pathways have been reported to synthesize miRNAs, including two major types: microprocessor-independent and Dicer-independent pathways.

A well-studied group of miRNAs that is generated without the use of microprocessors is the “mirtron”, which reside in the intronic regions of other genes (Westholm & Lai, 2011). Mirtrons were first identified in Drosophila and C. elegans and later also found in several mammalian species (Berezikov, Chung, Willis, Cuppen, & Lai, 2007; Okamura, Hagen, Duan, Tyler, & Lai, 2007; Ruby, Jan, & Bartel, 2007). Some mirtrons are conserved across several mammalian species, including miR-877, miR-1,224, and miR-1,225 (Berezikov et al., 2007). In the case of mirtrons, splicing machinery, instead of microprocessors, is responsible for the cleavage of pri-miRNAs to produce pre-miRNAs. In this case, the pri-miRNAs no longer have the “molecular rulers” (microprocessors) to safeguard the production of the typical 5′ and 3′ ends of pre-miRNAs. Alternative mechanisms are used to remove the extra nucleotides on the pre-miRNAs, including nuclease trimming by exosome exonuclease (Flynt, Greimann, Chung, Lima, & Lai, 2010; Westholm & Lai, 2011). Another microprocessor-independent pathway involves cleavage by transcription termination. A study identified “microprocessor-independent 7-methylguanosine (m7G)-capped pre-miRNAs”, exemplified by pre-miR-320, which are located near the 5’ end of the host transcripts and naturally form hairpin structures (Xie et al., 2013). Transcription termination generates the 3′ end of the pre-miRNA and the intact 5′ cap present in the pre-miRNA facilitates the nuclear export event.

Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis is relatively less studied. One example is miR-451. The pri-miR-451 undergoes microprocessor-mediated cleavage resulting in a short hairpin, which is further “sliced” by Ago2 and trimmed by the Poly(A) specific ribonuclease, PARN, to form the functional miRNA (Cheloufi, Dos Santos, Chong, & Hannon, 2010; Cifuentes et al., 2010).

2.3 |. miRNAs and miRNA host genes (MIRHGs)

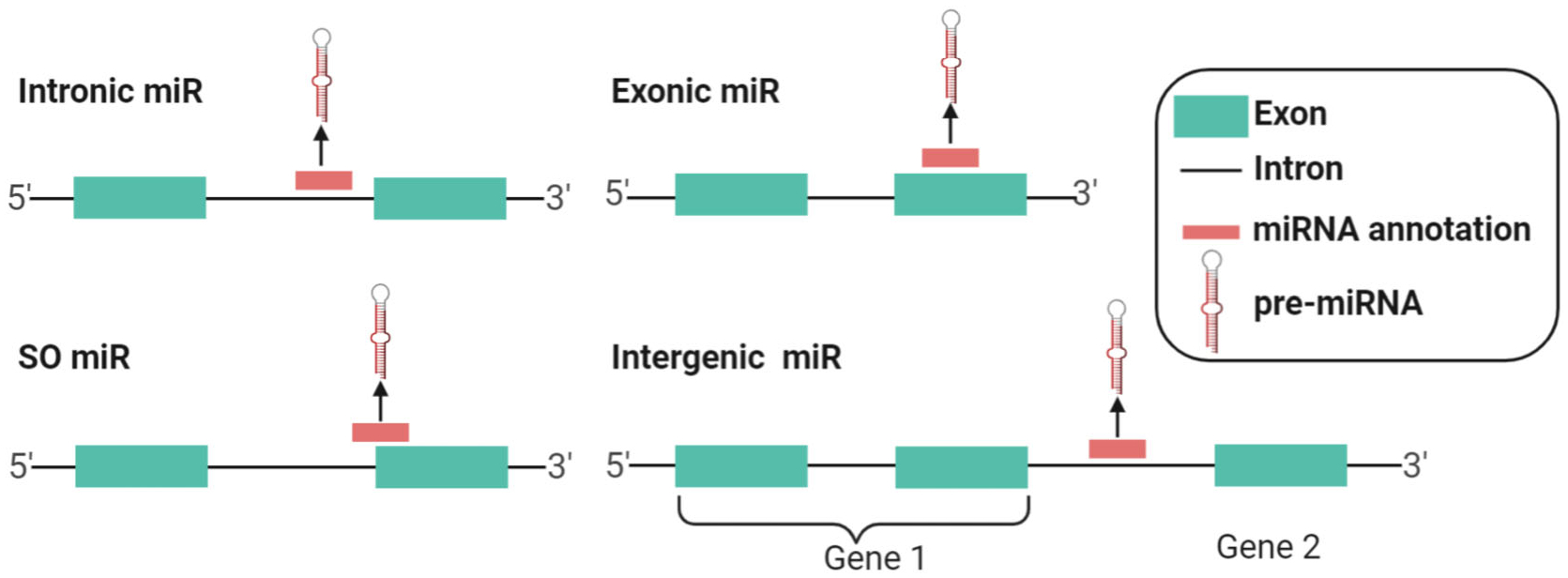

Only a small fraction (~28%) of miRNAs are transcribed from independent genomic loci (intergenic miRNAs) (Kahl, 2009). Rather, most miRNAs are hosted by the so-called miRNA-host-genes (MIRHGs), which include both protein-coding and lncRNA genes. These miRNAs are called “intragenic miRNAs”, including intronic, exonic, and splice site overlapping miRNAs (SO-miRNAs) (Mattioli, Pianigiani, & Pagani, 2014) (Figure 1). Intronic miRNAs constitute the largest portion of intragenic miRNAs (55%) (Kahl, 2009).

FIGURE 1.

Categorization of miRNAs with respect to their relationship with miRNA-host-genes (MIRHGs)

Several studies have reported correlated expression between miRNAs and their respective MIRHGs (Baskerville & Bartel, 2005; B. Liu, Shyr, Cai, & Liu, 2018; Lutter, Marr, Krumsiek, Lang, & Theis, 2010). An evolutionary study suggested that MIRHGs may provide increased expression constraints to their intragenic miRNAs during the course of evolution; “older” MIRHGs tend to display more correlated expression with the hosted miRNAs (Franca, Vibranovski, & Galante, 2016). Cancer cells epigenetically regulate the expression of MIRHGs to alter the levels of miRNAs. Several studies have identified that the promoters of MIRHGs showed altered methylation levels in certain cancers. As a result, the miRNAs encoded within these MIRHGs show differential expression, and can thus serve as cancer biomarkers. Some of these miRNAs have even been demonstrated to play crucial roles in cancer progression (Augoff, McCue, Plow, & Sossey-Alaoui, 2012; Daniunaite et al., 2017; Grady et al., 2008; Yeung, Tsang, Yau, & Kwok, 2017). Such studies also indicated that the methylation status of MIRHG promoters could be used as cancer biomarkers.

However, such co-regulated expression is not observed for all miRNA-MIRHG pairs. A significant number of studies have reported a lack of correlation and have shown that most miRNAs use independent promoters (Budach, Heinig, & Marsico, 2016; B. Liu et al., 2018; Steiman-Shimony, Shtrikman, & Margalit, 2018). For example, lncRNA DLEU2 is down-regulated in some pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients due to promoter methylation. However, the tumor suppressive miR-15a/16-a, which are embedded within DLEU2 gene, do not show decreased expression in these patients (Morenos et al., 2014). We will detail several more examples in a later part of this review.

Intragenic miRNAs also exert functional impacts on their host MIRHGs. One study predicted that ~1/5 of intragenic miRNAs could target their host mRNA transcripts, suggesting that these miRNAs are part of negative feedback loops to regulate the expression of their host genes (Hinske, Galante, Kuo, & Ohno-Machado, 2010). Additionally, miRNAs also target certain genes, which could in turn regulate the expression of their MIRHGs, hence facilitating/antagonizing the function of their MIRHG indirectly (Lutter et al., 2010; Steiman-Shimony et al., 2018). Lastly, the miRNAs that regulate the expression of their host MIRHGs are more conserved than the ones that impart no functional association with their host MIRHGs. This implies that organisms gain evolutionary advantage by utilizing miRNAs to coordinate the regulatory functions of their host genes (Steiman-Shimony et al., 2018).

2.4 |. Crosstalk between intragenic miRNA biogenesis and MIRHG splicing

The biogenesis and further processing of intragenic miRNAs and their corresponding MIRHGs are highly regulated events. Several studies have reported the interaction between members of the splicing machinery and microprocessors to modulate the syntheses of the miRNA and the mature MIRHG (Agranat-Tamir, Shomron, Sperling, & Sperling, 2014; Kataoka, Fujita, & Ohno, 2009). Based on our current knowledge, two major models recognized as the “synergic/cooperative model” and the “competitive model” are in place to explain the crosstalk between splicing and miRNA processing factors.

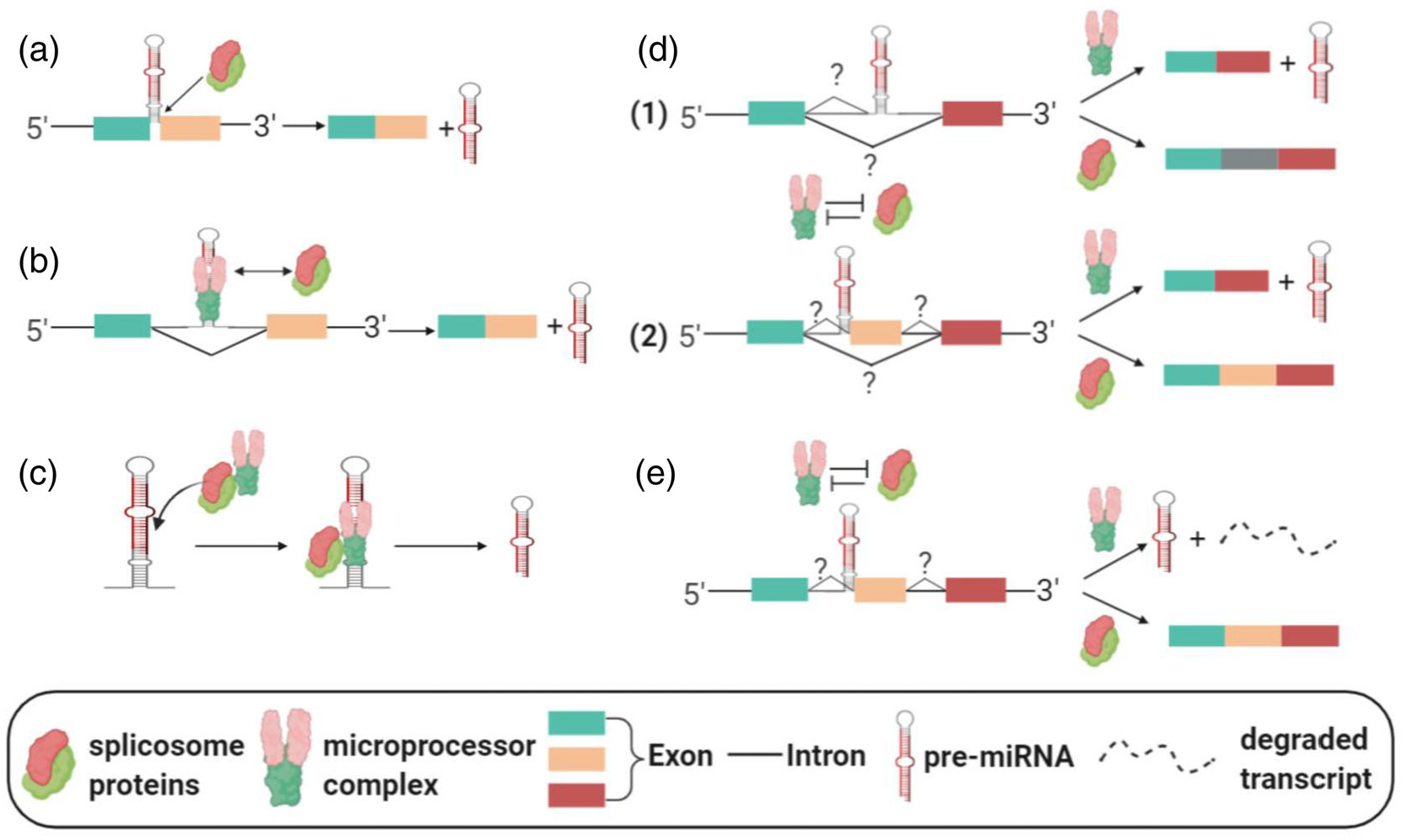

It has been reported that the cleavage of MIRHG transcripts by Drosha, a necessary event in canonical miRNA production, occurs co-transcriptionally and sometimes even before the splicing of introns (Y. K. Kim & Kim, 2007; Morlando et al., 2008). In the synergic/cooperative model, the splicing of MIRHGs facilitates the biogenesis of the miRNAs, and/or vice versa (Figure 2a–c). All mirtrons fall into this category, due to their dependence on MIRHG splicing as the means to generate pre-miRNAs (Figure 2a) (Berezikov et al., 2007; Westholm & Lai, 2011). Many splicing factors are shown to exert a positive influence on miRNA production (Figure 2b) (Ratnadiwakara, Mohenska, & Anko, 2018). An earlier study reported “mutually cooperative splicing and microprocessor activities” to achieve coordinated splicing and miRNA processing of intronic miRNAs (Janas et al., 2011). U1 snRNP, which recognizes the 5′ splice site of introns, facilitates the recruitment of Drosha to process intronic miR-211. Drosha in turn promotes splicing activity (Janas et al., 2011). In addition, SRSF3 was found to modulate the levels of many miRNAs by regulating splicing (Ajiro, Jia, Yang, Zhu, & Zheng, 2016). Another study reported that SRSF3 facilitates pri- to pre-miRNA processing by recruiting Drosha (K. Kim, Nguyen, Li, & Nguyen, 2018). Interestingly, studies have also identified “splicing-independent” functions of splicing factors in miRNA processing (Figure 2c). In this scenario, the splicing factors do not play their canonical roles to regulate gene splicing. Rather, they directly modulate the binding or activity of the microprocessor complex to regulate miRNA processing. Two proteins that are known to regulate gene splicing, hnRNPA1 and KSRP, have been found to bind to the stem-loop structure of the pri-miRNA to facilitate the microprocessor-mediated miRNA processing (Guil & Caceres, 2007; Trabucchi et al., 2009). SRSF1 (previously known as SF2/ASF) was also reported to promote the maturation of intronic miR-7, not by executing its splicing activity, but by directly regulating the cleavage by Drosha (Wu et al., 2010). Spliceosome-associated ISY1 was found to be required for the processing of the miR17 ~ miR-92 cluster during embryonic stem cell differentiation (P. Du, Wang, Sliz, & Gregory, 2015). Finally, several splicing-related proteins were shown to co-regulate miRNA biogenesis. HnRNPA1, which was introduced above, was found to negatively impact the processing of let-7a by antagonizing the binding of KSRP on pri-let-7a-1 (Michlewski & Caceres, 2010). Such cases, describing the “splicing-independent” function of splicing factors, cannot be identified as examples of the “synergetic model,” because of the lack of MIRHG splicing events. However, these studies still provide us with key insights into the molecular interplay between splicing factors and microprocessors in controlling miRNA biogenesis.

FIGURE 2.

Different models of MIRHG splicing and intragenic miRNA biogenesis. (a–c) Synergetic model. (a) Mirtron. (b) Splicing machinery and microprocessors facilitate each other. (c) Splicing factors facilitate miRNA production in a splicing-independent manner. (d,e) Competition model. (d) Alternative-splicing-mediated miRNA production. Two scenarios of alternative splicing are depicted. (e) Nonalternative-splicing-mediated miRNA production

On the other hand, several studies have reported data supporting the “competition model” (Figure 2d,e), in which the splicing factors compete with the miRNA-processing complex, especially when the miRNAs are located at the exon–intron junctions of MIRHGs (SO-miRNAs). MCM7 hosts miR-106b-25 in its intron. However, under certain conditions, by using alternative splicing to “transform” the miR-106b-25-containing intronic sequence to an exonic sequence, MCM7 no longer produces miRNAs from its nascent transcripts (Agranat-Tamir et al., 2014) (Figure 2d, Scenario 1). Other miRNAs that utilize similar mechanisms of biogenesis include mouse miR-412, human miR-202, human miR-34b, human miR-205, and human miR-612 (Mattioli, Pianigiani, & Pagani, 2013; Melamed et al., 2013; Profumo et al., 2019; X. Yang et al., 2018). In the case of mmu-miR-412, the alternative splicing event includes a cassette exon inclusion/exclusion and the miRNA is located at the splice junction (Melamed et al., 2013) (Figure 2d, Scenario 2). Lastly, miR-612 is hosted in the well-studied lncRNA nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1). A study showed that hepatocellular carcinoma cells can fine-tune the alternative splicing of NEAT1 to balance the relative concentrations of full-length NEAT1 and the miR-612, in order to regulate cell proliferation and metastasis (X. Yang et al., 2018).

In addition, the “competition model” also includes an “alternative splicing-independent” scenario (Figure 2e). A recent study from our laboratory has shown that MIR222HG nascent transcripts generate a multi-exonic lncRNA by enhancing the nascent RNA splicing during early serum response post-cellular quiescence (Q. Sun et al., 2020). During serum stimulation, the splicing factors compete with the microprocessor complex in order to facilitate the synthesis of the spliced lncRNA over pre-miRNA from the nascent MIR222HG transcripts. Our study found that the inhibition of splicing can increase the miR-222 production. Another study found that the pri- to pre-miRNA processing of several SO-miRNAs is not coupled with alternative splicing (Pianigiani et al., 2018). Both studies observed that the microprocessor cleavage causes the degradation of MIRHG transcripts. These findings imply that, in a particular scenario, nascent MIRHG transcripts “choose” a fate between gene splicing and SO-miRNA production (Figure 2e).

2.5 |. LncRNAs as miRNA host genes

LncRNAs have been sub-categorized based on their function/genomic location/expression patterns/subcellular distribution (St Laurent, Wahlestedt, & Kapranov, 2015). The biogenesis and function of several lncRNAs subtypes, such as antisense lncRNAs, cis-lncRNAs, and enhancer lncRNAs, are well explored, (Jadaliha et al., 2018; T. K. Kim, Hemberg, & Gray, 2015; Kopp & Mendell, 2018; Latge, Poulet, Bours, Josse, & Jerusalem, 2018). However, the miRNA-independent roles of the miRNA-host-gene-derived lncRNAs, which generate 17.5% of miRNAs in humans (Dhir, Dhir, Proudfoot, & Jopling, 2015), still remain to be elucidated. In the rest of this review, we use the term “lnc-MIRHG” to refer to these mature lncRNAs produced from the miRNA-host-gene loci.

The major question that needs to be addressed is whether lnc-MIRHG gene loci are merely serving as primary miRNA units for producing miRNAs, or if they might also generate mature lnc-MIRHGs that have independent roles. One study observed that upon depletion of microprocessors, several lnc-MIRHGs fail to terminate their transcription, resulting in the synthesis of nonfunctional and unstable readthrough transcripts. This study suggested that the microprocessor cleavage of lnc-MIRHGs causes transcription termination, whereas protein-coding MIRHGs use cleavage and polyadenylation-mediated termination (Dhir et al., 2015). Based on this study, the authors argued that lnc-MIRHGs merely serve as primary miRNAs and are not functional otherwise.

However, many recent studies from our laboratory as well as other groups have discovered that the mature transcripts produced from lnc-MIRHGs, which are fully spliced and polyadenylated, perform miRNA-independent functions. In the next part of this review, we will discuss the recent literature describing the miRNA-independent roles of several lnc-MIRHGs. We will also summarize the studies indicating the involvement of lnc-MIRHGs in cancer.

3 |. miRNA-INDEPENDENT ROLES OF lnc-MIRHG

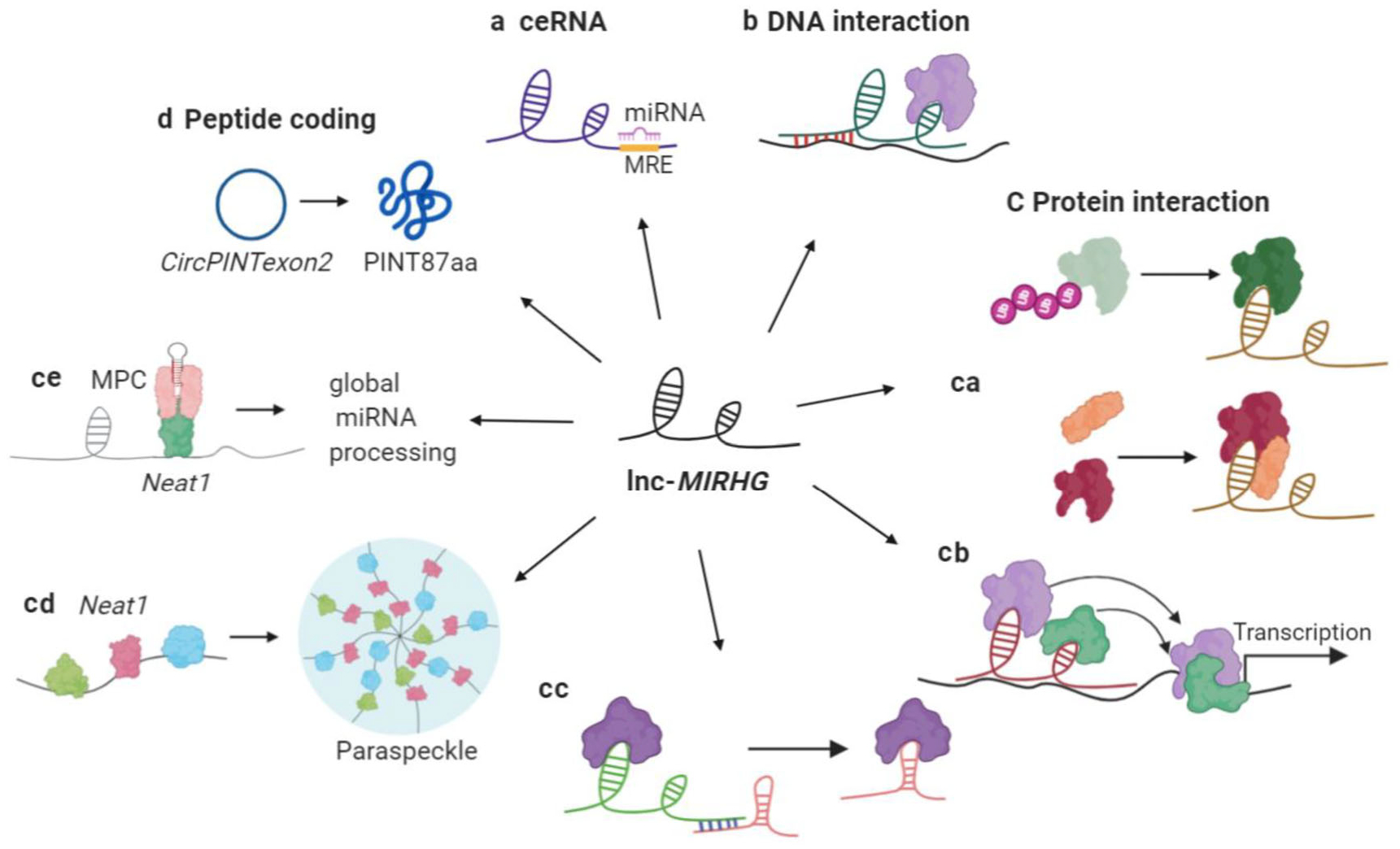

Studies from multiple groups have shown that lnc-MIRHGs perform functions that are independent of their role as miRNA precursors. Like other types of lncRNAs, lnc-MIRHGs also exert their functions via various mechanisms. Based on the current knowledge, we have summarized their molecular mechanisms into three major categories: “competing endogenous RNA (ceRNAs)”, “DNA interactors”, and “protein interactors” (Table 2, Figure 3). Of note, an individual lnc-MIRHG may perform multiple functions through non-overlapping mechanisms.

TABLE 2.

Molecular mechanisms of lnc-MIRHGs

| Class 1: Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | sponged_miRNA |

| DANCR | miR-4449 | miR-33a-5p (N. Jiang, Wang, et al., 2017) |

| H19 | miR-675 | miR-106a (Imig et al., 2015), let-7 (Kallen et al., 2013), review (Raveh, Matouk, Gilon, & Hochberg, 2015; L. Zhang et al., 2017) |

| LINC00472 | miR-30c2, -30a | miR-196a (Ye et al., 2018) |

| MEG3 | miR-2392, -770 | miR-181a (Peng et al., 2015) |

| MIR17HG | miR-17, -18a, -19a, -20a, -19b1, -92a1 | miR-375 (Xu et al., 2019) |

| MIR205HG | miR-205 | miR-590-3p (Di Agostino et al., 2018), miR-122-5p (Y. Li, Wang, & Huang, 2019) |

| MIR210HG | miR-210 | miR-503 (J. Li, Wu, Wang, & Zhang, 2017; A. H. Wang et al., 2020), miR-1226-3p (X. Y. Li, Zhou, et al., 2019) |

| MIR22HG | miR-22 | miR-141-3p (Cui, An, Li, Liu, & Liu, 2018) |

| MIR31HG | miR-31 | miR-193b (H. Yang et al., 2016) |

| MIR503HG | miR-503 | miR-103 (Fu et al., 2019) |

| NEAT1 | miR-612 | ceRNA (several, see review) (Dong et al., 2018; Ghafouri-Fard & Taheri, 2019) |

| PVT1 | miR-1204, -1205, -1206, -1207 | miR-143 (J. Chen et al., 2019), review (W. Wang, Zhou, et al., 2019) |

| Class 2: DNA binding | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Interacting DNA elements |

| MIR100HG | miR-125b1, -let7a2, -100 | DNA interaction (p27 promoter) (S. Wang, Ke, et al., 2018) |

| MIR205HG | miR-205 | Alu with nearby IRF binding site (Profumo et al., 2019) |

| Class 3: Protein-interaction | ||

| Subclass 3.1: Directly modulating the activity of interacting protein(s) | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Interacting protein and the corresponding impact |

| CYTOR/Linc00152 | miR-4435-1 | NCL and Sam68 (facilitate their association) (X. Wang, Yu, et al., 2018), β-catenin (blocks phosphorylation and change localization) (Yue et al., 2018) |

| LINC01138 | miR-5087 | PRMT5 (enhance stability) (Z. Li et al., 2018) |

| MIR22HG | miR-22 | YBX1 (enhance stability) (Su et al., 2018), HuR (regulate localization) (D. Y. Zhang, Zou, et al., 2018) |

| MIR4435-2HG | miR-4435-2 | β-Catenin (enhance stability) (Qian et al., 2018) |

| MIR503HG | miR-503 | hnRNPA2/B1 (promote degradation) (X. Wang, Yu, et al., 2018) |

| NEAT1 | miR-612 | inflammasomes proteins (facilitate assembly) (P. Zhang, Cao, Zhou, Yang, & Wu, 2019) |

| PVT1 | miR-1204, -1205, -1206, -1207 | NPO2 (enhance stability) (F. Wang et al., 2014) |

| Subclass 3.2: Transcriptional regulatory effect via interacting proteins | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Interacting protein and the effect on transcription |

| H19 | miR-675 | Several, including EZH, MBD1 (Monnier et al., 2013), hnRNPU (Raveh et al., 2015; L. Zhang et al., 2017) |

| LINC-PINT | miR-29b1 | PRC2 (Marin-Bejar et al., 2013; Marin-Bejar et al., 2017) |

| MEG3 | miR-2392, -770 | JARID2 and EZH2 (Terashima, Tange, Ishimura, & Suzuki, 2017) |

| MEG8 | miR-370, -379, -411, -299, -380, -1,197, -323a, -758, -329-–1, -329-2, -494, -1193, -543, -495 | EZH2 (Terashima, Ishimura, Wanna-Udom, & Suzuki, 2018) |

| MIR2052HG | miR-2052 | EGR1 (Cairns et al., 2019) |

| MIR205HG | miR-205 | Pit1, Zbtb20 (Q. Du et al., 2019), IRF (Profumo et al., 2019) |

| MIR210HG | miR-210 | DNMT1 (Kang et al., 2019) |

| MIR31HG | miR-31 | HIF-1α (Shih et al., 2017) |

| NEAT1 | miR-612 | EZH2 (Q. Chen, Cai, et al., 2018; S. Wang, Zuo, et al., 2019), SFPQ (Hirose et al., 2014) |

| PVT1 | miR-1204, -1205, -1206, -1207 | EZH2 (Kong et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2016; S. Zhang, Zhang, & Liu, 2016) |

| RMST | miR-1251, -135a2 | SOX2 (Ng, Bogu, Soh, & Stanton, 2013) |

| Subclass 3.3: Post-transcriptional regulatory effect via interacting proteins | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Interacting protein and the corresponding impact |

| H19 | miR-675 | KSRP (increase KSRP-RNA interaction) (Giovarelli et al., 2014) |

| MIR100HG | miR-125b1, -let7a2, -100 | HuR (increase HuR-target RNA interaction) (Q. Sun, Hao, et al., 2018) |

| MIR22HG | miR-22 | SMAD2 (decrease SMAD2-SMAD4 interaction) (Xu et al., 2020), HuR (decrease HuR-target RNA interaction) (D. Y. Zhang, Zou, et al., 2018) |

| MIR222HG | miR-221, miR-222 | ILF3/ILF2 (maintains DNM3OS stability) (Q. Sun et al., 2020) |

| Subclass 3.4: Other roles via interacting proteins | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Interacting protein and corresponding impact |

| NEAT1 | miR-612 | NONO-SFPQ (global regulation of pri-miRNA processing (L. Jiang, Shao, et al., 2017) 1, NONO and other proteins (initiates paraspeckle assembly (Yamazaki et al., 2018) |

| Class 4: Lnc-MIRHGs exerts function by producing small peptides | ||

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Peptide information |

| LINC-PINT | miR-29b1 | PINT87aa encoded by CircPINTexon2 (M. Zhang et al., 2018) |

FIGURE 3.

Molecular mechanisms of lnc-MIRHGs. (a) ceRNA. (b) Interacting with DNA elements. (c) Interacting with proteins. (ca) Regulating the interacting protein(s). Top: stabilizing the interacting protein. Bottom: mediating protein–protein interaction. (cb) Recruiting/titrating protein factors to regulate transcription. (cc) Recruiting/titrating protein factors to regulate post-transcriptional regulation. (cd) Global regulation of primary RNA processing (NEAT1). (ce) Maintaining nuclear structure (NEAT1).(d) Peptide encoding. Example is the circular LINC-PINT

Some lncRNAs have been reported to serve as ceRNAs by “sponging” certain miRNAs, thereby inhibiting the miRNA function. To be defined as a “ceRNA”, a lncRNA needs to contain one or more miRNA recognition elements to sponge the miRNAs. The luciferase reporter assay is a classic method that is used to confirm the predicted miRNA binding sites on a lncRNA (Jin, Chen, Liu, & Zhou, 2013). In the case of the ceRNA model, the loss of a potential ce-lncRNA will release the “sponged” miRNAs such that these miRNAs will be available to inhibit the expression of their target mRNAs, hence a concomitant decrease in the levels of those target mRNAs would be expected. We summarize the lnc-MIRGHs that mechanistically behave as ceRNAs (Table 2, Class 1, Figure 3a). The function of these “ce-lnc-MIRHGs” is exerted via a “lnc-MIRHG-sponged miRNA-target mRNA” axis.

LncRNAs can also directly interact with DNA elements, such as promoters, to form RNA-dsDNA triplex structures and further recruit protein factors to regulate the DNA activity, such as transcription (Bacolla, Wang, & Vasquez, 2015). Two lnc-MIRHGs, MIR100HG and MIR205HG, fall in this category (Table 2, Class 2, Figure 3b).

LncRNAs can also regulate cellular functions via modulating protein activity (Marchese et al., 2017). In this review, we further categorize the “protein interactors” into several subclasses (Table 2, Class 3, Figure 3c). Subclass 3.1 includes the group of lnc-MIRHGs that influence the interacting protein(s) by regulating their modification, stability, or complex assembly (Figure 3ca). Lnc-MIRHGs in Subclasses 3.2 and 3.3 function by acting as a scaffold or by recruiting or titrating the interacting proteins to/from their destinations, in order to regulate transcriptional (Figure 3cb) or post-transcriptional (Figure 3cc) events. Two additional nonoverlapping mechanisms utilized by NEAT1 are categorized into Subclass 3.4 (NEAT1) (Figure 3cd,ce).

Finally, lncRNAs have also been reported to generate short functional peptides (Table 2, Class 4, Figure 3d). LINC-PINT is a lnc-MIRHG under this category, and will be discussed in detail later.

3.1 |. MIR22HG

MIR22HG shows tumor-suppressive roles in multiple cancers (Table 3). In endometrial cancer, it acts as an anti-proliferative ceRNA and sponges miR-141–3p to increase the RNA and protein levels of DAPK1 (Cui et al., 2018). In colorectal cancer, MIR22HG, by competitively interacting with SMAD2, disrupts the SMAD2-SMAD4 interaction and thereby perturbs TGFβ signaling pathway (Xu et al., 2020). MIR22HG was also shown to interact with HuR to maintain the nuclear localization of HuR. In addition, by competitively interacting with HuR, MIR22HG reduced the binding of HuR to several of its oncogenic mRNA targets, including β-catenin, resulting in reduced expression of these oncogenes (D. Y. Zhang, Zhao, et al., 2018). Finally, in lung cancer, MIR22HG was found to interact with YBX1 to stabilize YBX1 levels. MIR22HG-YBX1 in turn modulates the expression of cancer-associated genes such as MET and p21 (Su et al., 2018).

TABLE 3.

Function of lnc-MIRHGs in different types of cancer

| Lnc-MIRHG | Encoded miRNA | Cancer | Oncogenic (Onc) or tumor suppressor (Ts) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCDC26 | miR-3686 | Childhood acute myeloid leukemia (Hirano et al., 2015), pancreatic cancer (Peng & Jiang, 2016) | Onc (Hirano et al., 2015; Peng & Jiang, 2016), Ts (Hirano et al., 2015) |

| CYTOR/Linc00152 | miR-4435-1 | colorectal cancer (X. Wang, Yu, et al., 2018), Colon Cancer (Yue et al., 2018) | Onc |

| DANCR | miR-4449 | Osteosarcoma (N. Jiang, Wang, et al., 2017), Colorectal Cancer (Y. Liu, Zhang, Liang, Li, & Chen, 2015) | Onc |

| FTX | miR-421, -374a, -374b, -545 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (Z. Liu et al., 2016; Q. Zhao, Li, Qi, Liu, & Qin, 2014) | Onc |

| H19 | miR-675 | Multiple cancer (Raveh et al., 2015; Yoshimura, Matsuda, Yamamoto, Kamiya, & Ishiwata, 2018; L. Zhang et al., 2017) | Onc |

| LINC00472 | miR-30c2, -30a | Breast cancer (Shen et al., 2015), colorectal cancer (Ye et al., 2018) | Ts |

| LINC01138 | miR-5087 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (Z. Li et al., 2018) | Onc |

| LINC-PINT | miR-29b1 | Colorectal cancer, lung adenocarcinoma (Marin-Bejar et al., 2017), glioblastoma (circular form, peptide encoding) (M. Zhang, Zhao, et al., 2018) | Ts |

| MEG3 | miR-2392, -770 | Non-small cell lung cancer (K. H. Lu et al., 2013), gastric cancer (Peng et al., 2015) | Ts |

| MEG8 | miR-370, -379, -411, -299, -380, -1197, -323a, -758, -329-1, -329-2, -494, -1193, -543, -495 | Pancreatic cancer, lung cancer (Terashima et al., 2018) | Onc |

| MIR100HG | miR-125b1, -let7a2, -100 | Colorectal cancer (Y. Lu et al., 2017), breast cancer (S. Wang, Ke, et al., 2018), acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (Emmrich et al., 2014), osteosarcoma (Q. Sun, Hao, et al., 2018) | Onc |

| MIR17HG | miR-17, -18a, -19a, -20a, -19b1, -92a1 | Colorectal cancer (Xu et al., 2019) | Onc |

| MIR2052HG | miR-2052 | Breast cancer (Cairns et al., 2019; Ingle et al., 2016) | Onc |

| MIR205HG | miR-205 | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (Di Agostino et al., 2018), cervical cancer (Y. Li, Wang, & Huang, 2019) | Onc |

| MIR210HG | miR-210 | Osteosarcoma (J. Li, Wu, et al., 2017), cervical cancer (A. H. Wang et al., 2020), breast cancer (X. Y. Li, Zhou, et al., 2019), lung cancer (Kang et al., 2019) | Onc |

| MIR222HG | miR-221, 222 | prostate cancer (T. Sun, Du, et al., 2018) | Onc |

| MIR22HG | miR-22 | Lung cancer (Su et al., 2018), hepatocellular carcinoma (D. Y. Zhang, Zou, et al., 2018), endometrial cancer (Cui et al., 2018), colorectal cancer (Xu et al., 2020), | Ts |

| MIR31HG | miR-31 | Oral squamous cell carcinoma (Shih et al., 2017), lung adenocarcinoma (Qin et al., 2018), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (H. Yang et al., 2016), gastric cancer (Nie et al., 2016) | Onc (Qin et al., 2018; Shih et al., 2017; H. Yang et al., 2016) Ts (Nie et al., 2016) |

| MIR4435-2HG | miR-4435-2 | Lung cancer (Qian et al., 2018), gastric cancer (H. Wang, Wu, et al., 2019) | Onc |

| MIR503HG | miR-503 | Hepatocellular carcinoma (H. Wang, Liang, et al., 2018), breast cancer (Fu et al., 2019), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (Huang et al., 2018) | Onc (Huang et al., 2018), Ts (Fu et al., 2019; H. Wang, Liang, et al., 2018) |

| MIR99AHG/MONC | miR-99A, -let7c, -125b2 | Leukemia (Emmrich et al., 2014) | Onc |

| PVT1 | miR-1204, -1205, -1206, -1207 | Multiple cancers (J. Chen et al., 2019; Colombo, Farina, Macino, & Paci, 2015; Derderian, Orunmuyi, Olapade-Olaopa, & Ogunwobi, 2019; Kong et al., 2015; Olivero et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2016; F. Wang et al., 2014; W. Wang, Zhou, et al., 2019; S. Zhang et al., 2016) | Onc and Ts |

| RMST | miR-1251, -135a2 | Triple-negative breast cancer (L. Wang, Liu, et al., 2018) | Ts |

| SNHG20 | miR-6516 | Multiple cancers (W. Zhao et al., 2019) | Onc |

| NEAT1 | miR-612 | Multiple cancers (Dong et al., 2018; Ghafouri-Fard & Taheri, 2019) | Onc and Ts |

3.2 |. MIR100HG

Our laboratory previously reported that the MIR100HG gene locus produces a multi-exonic nuclear lncRNA, which is highly expressed in the G1 phase of the cell cycle in osteosarcoma cells (U2OS). The encoded miRNAs, however, do not display the cell cycle-dependent dynamic expression pattern. MIR100HG is required for cell cycle progression in a miRNA-independent manner. Mechanistically, MIR100HG contains U-rich sequences that facilitate its interaction with both HuR and several HuR target RNAs. MIR100HG serves as a “scaffold” to facilitate HuR-target RNA association, which is required to stabilize the cellular levels of these target RNAs and their corresponding proteins (T. Sun, Du, et al., 2018). Another study showed that MIR100HG plays an oncogenic role in breast cancer by directly interacting with the promoter of CDKN1B (p27) to form a triplex structure, which attenuates the transcription of CDKN1B (S. Wang, Ke, et al., 2018).

3.3 |. MIR31HG

MIR31HG is a hypoxia-induced lncRNA that plays crucial roles in the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma (Shih et al., 2017). MIR31HG uses its 5′ terminal region to interact with the PAS-B domain of HIF-1α. This interaction facilitates the assembly of the HIF-1 complex and enhances the chromatin recruitment of HIF-1α and p300 cofactor to their target gene promoters, thereby promoting the HIF-1 transcriptional network. MIR31HG, hence, is annotated as “LncHIFCAR” (long nc HIF-1a co-activating RNA) in this study. Another study identified MIR31HG as a ceRNA of miR-193b in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In this study, MIR31HG was shown to negatively regulate the miR-193b-mediated destabilization of CCND1 and KRAS (H. Yang et al., 2016).

3.4 |. MIR205HG/LEADeR

MIR205HG is an intriguing lnc-MIRHG that is involved in several diverse functions and molecular mechanisms. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and cervical cancer, MIR205HG was shown to act as an oncogenic ceRNA. By quenching the cellular pool of miR-590–3p and miR-122–5p, MIR205HG enhances the levels of pro-proliferative or oncogenic genes (Di Agostino et al., 2018; Y. Li, Zhou, et al., 2019). MIR205HG also negatively regulates the differentiation of prostate cancer cells by suppressing the expression of several genes whose promoters contain Alu elements and inter-feron regulatory factor (IRF) binding sites (Profumo et al., 2019). MIR205HG directly binds to the promoters of genes, which contain Alu and IRF binding sites, via Alu-mediated intermolecular interactions. Mechanistically, MIR205HG inhibits the binding of IRF to the IRF elements of several target genes, which are required for basal-luminal differentiation, resulting in their transcription repression (Profumo et al., 2019). Finally, another study demonstrated that MIR205HG is expressed in regions that specify the anterior pituitary during mouse embryogenesis (Q. Du et al., 2019). During development, MIR205HG regulates growth hormone and prolactin production by forming complexes with Pit1 and Zbtb20 transcription factors in order to enhance the transcription of Prolactin, Gh (growth hormone) and Pit1 (Q. Du et al., 2019). These studies clearly demonstrate the lncRNA-specific function of the MIR205HG locus in cancer differentiation and mouse neuronal development.

3.5 |. RMST

RMST is a multi-exonic and conserved lncRNA that harbors miR-1251 and miR-135a2 in its intron. During neuronal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells, the RMST level is induced to facilitate the differentiation process via its interaction with SOX2, which is an important transcription factor for neuronal fate determination. Mechanistically, RMST promotes the global binding of SOX2 to its target genes, thereby facilitating neuronal differentiation (Ng et al., 2013).

3.6 |. CYTOR

CYTOR is a lnc-MIRHG that hosts miR-4435–1 and plays oncogenic roles in colorectal cancer. In colorectal cancer, it forms a heterotrimeric complex with Nucleolin and Sam68 via its first exon, and thus facilitates Nucleolin and Sam68 complex assembly. The CYTOR-NCL-Sam68 complex promotes the progression of colorectal cancer by activating the downstream NF-κB pathway (X. Wang, Yu, et al., 2018). Another study showed that CYTOR promotes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis in colon cancer. Mechanistically, CYTOR interacts with β-catenin to prevent the phosphorylation of cytoplasmic β-catenin by casein kinase 1 (CK1), thereby facilitating its nuclear translocation and transcription promoting activity (Yue et al., 2018).

3.7 |. LINC01138

LINC01138, which hosts miR-5087, is transcribed from a frequent DNA-gain region in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Z. Li et al., 2018). Elevated expression of LINC01138 promoted cell growth and metastasis of HCC cells and was identified as a prognostic marker of HCC patients. Mechanistically, LINC01138 interacts with the protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) to increase the stability of PRMT5 by blocking its ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent degradation. Hence, LINC01138 is recognized as an oncogenic driver through its role in stabilizing the PRMT5 levels in HCC. It would be important to test if LINC01138 plays such an oncogenic role in other types of cancer that are sensitive to PRMT5 levels.

3.8 |. LINC-PINT

LINC-PINT or Pint was initially identified in a mouse study. This lnc-MIRHG is induced by p53, hence named “p53-induced non-coding transcript” (Marin-Bejar et al., 2013). It plays a tumor suppressive role by inhibiting the migration and invasion of colorectal cells in vitro and in vivo (Marin-Bejar et al., 2017). Mechanistically, LINC-PINT has been shown, in both mouse and humans, to interact with PRC2 and mediate PRC2 targeting to different genes for their transcriptional silencing (Marin-Bejar et al., 2013; Marin-Bejar et al., 2017). For example, in colorectal cancer, LINC-PINT promotes the PRC2-mediated repression of genes with invasion signature, such as EGR1 and FOS (Marin-Bejar et al., 2017). Another recent study reported that a circular RNA, CircPINTexon2, is processed from the second exon of LINC-PINT by back-splicing (M. Zhang, Zou, et al., 2018). The cytoplasmic CircPINTexon2 encodes an 87-amino-acid peptide, PINT87aa, which inhibits the proliferation of glioblastoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistic studies revealed that PINT87aa peptide interacts with PAF1 (RNA pol II-associated factor 1) to inhibit the transcriptional elongation of multiple oncogenes, including CPEB1, SOX2, and c-Myc. This is a classic example where a lncRNA and a peptide are synthesized from the same lncRNA locus to play independent activities as tumor suppressors.

3.9 |. MIR503HG

MIR503HG was identified as another tumor suppressor lnc-MIRHG. A study using the HCC model demonstrated that MIR503HG inhibits HCC cell invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo (H. Wang, Liang, et al., 2018). MIR503HG interacts with the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (hnRNPA2B1) and facilitates the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of hnRNPA2B1. The MIR503HG-mediated degradation of hnRNPA2B1 further results in reduced mRNA stability of p52 and p65 as well as protein levels of multiple NF-κB downstream effectors, thereby inhibiting cancer cell metastasis. In triple-negative breast cancer, MIR503HG was reported to function as a ceRNA of miR-103 to protect the levels of the miR-103 target tumor suppressor gene, olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) (Fu et al., 2019). In the case of MIR503HG, it modulates the protein stability in one instance, but then performs a completely different function, as a ceRNA in another scenario, indicating that lnc-MIRHGs could participate in versatile functions in a tissue or cell-line specific fashion.

3.10 |. NEAT1

NEAT1 (Nuclear-enriched abundant transcript 1) is a well-known “structural determinant lncRNA”, which maintains the structural integrity of paraspeckles (Clemson et al., 2009). It is also a lnc-MIRHG that harbors miR-612. A recent study revealed that paraspeckle structure exhibits phase-separated properties and NEAT1 is necessary and sufficient for paraspeckle assembly. NEAT1 contains several domains, within which each domain executes important functions, including RNA stability, isoform switching, and paraspeckle assembly (Yamazaki et al., 2018). For example, the middle domain of NEAT1, which is located within the inner core of the paraspeckle, controls paraspeckle assembly. Hirose and colleagues observed that the middle domain of NEAT1 recruits NONO protein dimers to initiate assembly of the paraspeckle structure (Yamazaki et al., 2018). The 5′ and 3′ termini are located on the outer shell of the paraspeckle (Souquere, Beauclair, Harper, Fox, & Pierron, 2010). The 3′ terminus of NEAT1 contains a triple helix structure, which modulates RNA stability, and the 5′ terminal domain functions in regulating the stability and transcription of NEAT1. NEAT1 has also been reported to repress the transcription of several genes, including ADARB2. Mechanistically, NEAT1 sequesters the splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich (SFPQ) away from ADARB2 promoters to paraspeckles (Hirose et al., 2014).

NEAT1 was also identified as an oncogene or a tumor suppressor gene in a context-dependent manner. Several mechanisms were proposed to address the oncogenic or tumor suppressor activity of NEAT1 (see reviews Dong et al., 2018; Ghafouri-Fard & Taheri, 2019). For example, NEAT1 promotes glioblastoma progression by promoting the β-catenin nuclear transport (Q. Chen, Cai, et al., 2018). Recently, the Chen lab reported a novel role for NEAT1 in modulating the intracellular dynamics of mRNAs coding for mitochondrial proteins (Y. Wang, Hu, et al., 2018). These studies and many others identified NEAT1 as a lncRNA with versatile functions. NEAT1 is a widely studied lncRNA implicated in a variety of biological functions and diseases, which are beyond the scope of this review, but numerous excellent reviews on NEAT1 have already been published covering different aspects of its functions/roles (An, Williams, & Shelkovnikova, 2018; Y. Chen, Qiu,, et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2018; Fox & Lamond, 2010; Ghafouri-Fard & Taheri, 2019; Naganuma & Hirose, 2013; Riva, Ratti, & Venturin, 2016; C. Yang et al., 2017; Yu, Li, Zheng, Chan, & Wu, 2017).

A recent study also recognized NEAT1 as a pseudo-MIRHG (L. Jiang, Shao, et al., 2017). The authors revealed that the cellular level of miR-612, which is harbored within NEAT1, is below the detectable level, indicating the inefficient production of miR-612 from the abundant NEAT1 lnc-MIRHG transcripts. This study showed that miR-612 serves as a “pseudo-miRNA” to recruit the microprocessor to NEAT1, thereby facilitating the interactions between the microprocessor and the NEAT1-bound NONO-PSF (SFPQ) complex. The NEAT1-NONO/PSF-microprocessor complex enhances global pri-miRNA processing. This study has brought novel insights into the role of a nuclear domain architectural lnc-MIRHG in nuclear miRNA processing.

3.11 |. PVT1

PVT1 is a famous oncogenic lncRNA, which is processed from the lnc-MIRHG locus that harbors several miRNAs, including miR-1204, -1205, -1206, -1207 (3p and 5p), and -1208. The PVT1 gene is located in genomic proximity to the c-Myc oncogene, and has been shown to positively regulate c-Myc expression and activity (Tseng et al., 2014) (Table 3). In addition, PVT1 was shown to sponge many tumor suppressive miRNAs (see review W. Wang, Zhou, et al., 2019). Finally, PVT1 inhibits the expression of several tumor suppressor genes, including LATS2, CDKN2B (p15), CDKN2A (p16), and miR-200 genes (Kong et al., 2015; Wan et al., 2016; S. Zhang et al., 2016) by recruiting EZH2 to their promoters to establish a repressive chromatin mark. All of these studies clearly established PVT1 as an oncogene (Colombo et al., 2015). However, a recent study from the Dimitrova laboratory identified a DNA damage-induced isoform of PVT1 (Pvt1b) as an inhibitor of c-myc transcription (Olivero et al., 2020). The authors observed that p53 induces the expression of the Pvt1b isoform during DNA damage or during oncogenic signaling. By utilizing various approaches, the authors demonstrated the tumor suppressor activity of Pvt1b, primarily by its role in inhibiting c-myc transcription. This study highlights an important idea that different isoforms of a particular lncRNA could perform entirely opposite functions in response to various cellular signals.

3.12 |. H19

H19 is the first identified mammalian lncRNA (Brannan, Dees, Ingram, & Tilghman, 1990). It is transcribed from the genomically imprinted H19/IGF2 cluster and displays maternal monoallelic expression. The H19 gene locus harbors miR-675. A previous study reported that H19 inhibits the growth of the placenta before birth via modulating the processing of miR-675, whose targets include growth-promoting insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) (Keniry et al., 2012). H19 is also widely known as an oncogenic lncRNA (Raveh et al., 2015). H19 adopts a wide spectrum of mechanisms to control gene expression. First, the H19-miR-675 axis functions via suppressing different miR-675 mRNA targets, including SMAD and TGFβ1 (Raveh et al., 2015; L. Zhang et al., 2017). H19 also serve as a ceRNA to sponge miRNAs including let-7a and miR-106a (Imig et al., 2015; Kallen et al., 2013). Lastly, H19, as reported in different studies, interacts with protein partners, including EZH, MBD1, hnRNPU, and KSRP and influences their activity. The various molecular mechanisms allow H19 to control multiple biological processes, including those relevant to cancer, such as cell proliferation and EMT. H19 has been extensively well studied. We recommend two excellent reviews on H19 lncRNA to learn more about this enigmatic lncRNA (Raveh et al., 2015; L. Zhang et al., 2017).

3.13 |. MIR222HG

A previous study has reported that lncRNA MIR222HG is upregulated in castration-resistant prostate cancer cells to increase androgen-independent cell growth (T. Sun, Du, et al., 2018). Recently, our laboratory discovered MIR222HG’s role in facilitating cell cycle re-entry post-cellular quiescence (Q. Sun et al., 2020). Interestingly, we found that upon early serum-stimulation, diploid fibroblasts enhance the splicing of the host nascent pri-MIR222HG transcript dramatically and show increased levels of spliced MIR222HG. The pre-mRNA splicing factor SRSF1 associates with the nascent MIR222HG transcripts and negatively regulates the miRNA processing of miR-221/222. Mechanistically, the spliced MIR222HG lncRNA facilitates cell cycle re-entry by interacting with the ILF3/2 complex and several other RNAs to form an RNP complex. Our study demonstrates that the competition between the splicing and microprocessor machinery fine-tunes the cellular levels of lncRNA MIR222HG that dictates cell cycle re-entry.

4 |. EMERGING ROLES OF LNC-MIRHGS IN CANCER

The last few years have seen a rapid increase in the number of publications demonstrating the involvement of lncRNAs in cancer. The decreased cost of next-generation sequencing, advances in computational and statistical pipelines, and the increased resources of cancer databases have provided us with a great opportunity to identify cancer-related lncRNAs. Many studies have reported aberrant lncRNA expression in tumor or cancer cells. In the clinical setting, lncRNAs have been identified as diagnosis or prognosis markers in patients. LncRNAs also regulate crucial molecular events during cancer cell proliferation or tumor metastasis (Huarte, 2015; Schmitt & Chang, 2016). The discovery of lncRNA function in cancer is important for drug discovery and cancer treatment.

miRNAs are also found to play key roles in cancer. The expression relationship or functional association between miRNA and their host genes in cancer have been studied and summarized by a previous review (B. Liu et al., 2018). In the current review, we only focus on the function of lnc-MIRHGs in cancer. Many groups have performed meta-analysis of tumor samples and reported several lnc-MIRHGs as biomarkers or prognosis markers of certain cancer types. These studies provide us with great resources to carry on further investigations on the molecular functions of lnc-MIRHGs. In this review, we only summarize studies that have included experimentally proven functions of lnc-MIRHGs (Table 3).

We have categorized the lnc-MIRHGs into oncogenic (Onc) or tumor suppressor (Ts) groups. A typical oncogenic lnc-MIRHG shows upregulation in certain tumor/cancer cell lines. Its high expression is typically associated with poor prognosis in patients. Functional assessment in cell lines or animal models further proves the oncogenic activity of the lnc-MIRHG, which usually includes one or more of the following: promoting cell proliferation, causing larger tumor size in animal models, and enhancing migration or invasion of cancer cells. A tumor suppressor lnc-MIRHG usually displays the opposite features.

Based on the summary in Table 3, one could observe that a particular lnc-MIRHG may participate in tumor progression in various cancer types. In addition, several lnc-MIRHGs function as an oncogene in one cancer model but demonstrate tumor suppressor activity in another cancer model (including CCDC26, MIR31HG, MIR503HG, PVT1, NEAT1), implying that they perform cancer-specific functions.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The human genome contains a large number of genomic loci that could produce multiple transcripts. For example, bifunctional RNAs, or bifRNAs, are RNAs that are functional in the form of both mRNA and nc RNA (lncRNA/snoRNA/miRNA) (Hube & Francastel, 2018). BifRNAs have been identified from bacteria to mammals (Aspden et al., 2014; Gimpel, Heidrich, Mader, Krugel, & Brantl, 2010; Ji, Song, Regev, & Struhl, 2015; Lauressergues et al., 2015). Cells can precisely modulate the functions of the coding and nc portions of the bifRNAs to meet corresponding regulatory needs. However, it has not been thoroughly tested whether the same gene locus can produce two types of functional nc transcripts, for instance, lncRNAs and miRNAs. These “bifunctional nc RNAs” are the focus of this review.

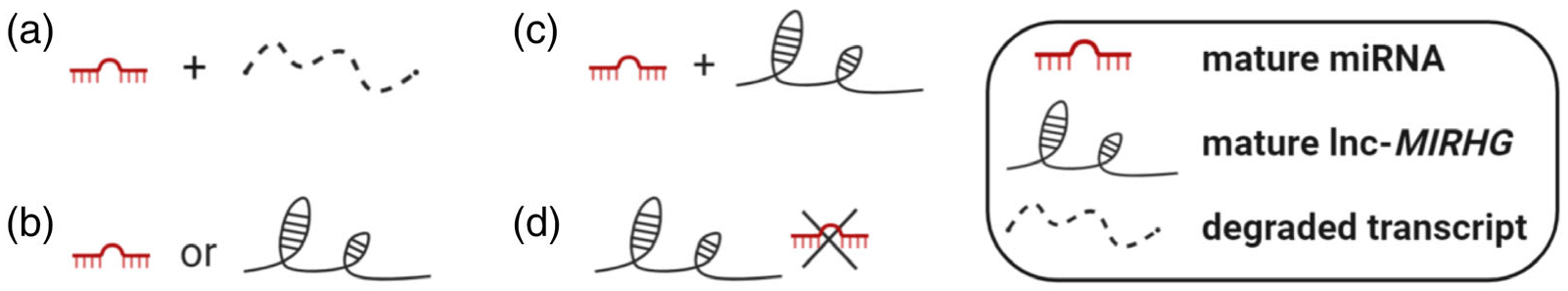

In this review, we have summarized the current knowledge of lnc-MIRHGs. These functional and mechanistic studies have proven that not all lnc-MIRHGs are “junk transcripts” (Figure 4a). Rather, the lnc-MIRHG loci can produce both functional miRNAs and lncRNAs, which might function synergistically or independently (Figure 4b,c). The studies of NEAT1 also suggest that the miRNA can be the “pseudo-RNA” while the lncRNA produced from lnc-MIRHG gene locus plays the dominant role (Figure 4d). Collectively, the beauty of those lnc-MIRHG loci, dictated by their potential dual functions from both the lncRNA and miRNA, strongly suggests that we should pay more attention to this class of lncRNAs. Lnc-MIRHGs display a whole spectrum of functions, especially in diseases such as cancer. Having a good understanding of the mechanisms of this lncRNA repertoire will be beneficial for drug design and development.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of lnc-MIRHG loci outcome. (a) Only generates miRNA; the lnc-MIRHG nascent transcript degrades quickly. (b) The loci only produces one type of ncRNA: either miRNA or lnc-MIRHG can be generated. (c) The loci can produce both miRNA and lnc-MIRHG. (d) The loci exerts low miRNA production efficiency and only produces lnc-MIRHG (NEAT1 example)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Q. Hao and Ms. M. Kovour for proofreading the manuscript. All figures were created using BioRender. com. Work in the Prasanth KV Lab is funded by grants from National Institute of Health (R21AG065748), Cancer Center at Illinois seed grant, and Prairie Dragon Paddlers and NSF (EAGER; MCB1723008).

Funding information

Cancer center at Illinois seed grant and Prairie Dragon Paddlers; National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: R21AG065748; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: MCB1723008

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

REFERENCES

- Agranat-Tamir L, Shomron N, Sperling J, & Sperling R (2014). Interplay between pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA biogenesis within the supraspliceosome. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(7), 4640–4651. 10.1093/nar/gkt1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajiro M, Jia R, Yang Y, Zhu J, & Zheng ZM (2016). A genome landscape of SRSF3-regulated splicing events and gene expression in human osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(4), 1854–1870. 10.1093/nar/gkv1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Williams NG, & Shelkovnikova TA (2018). NEAT1 and paraspeckles in neurodegenerative diseases: A missing lnc found? Non-coding RNA Research, 3(4), 243–252. 10.1016/j.ncrna.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspden JL, Eyre-Walker YC, Phillips RJ, Amin U, Mumtaz MA, Brocard M, & Couso JP (2014). Extensive translation of small open Reading frames revealed by poly-Ribo-Seq. eLife, 3, e03528. 10.7554/eLife.03528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augoff K, McCue B, Plow EF, & Sossey-Alaoui K (2012). miR-31 and its host gene lncRNA LOC554202 are regulated by promoter hypermethylation in triple-negative breast cancer. Molecular Cancer, 11, 5. 10.1186/1476-4598-11-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auyeung VC, Ulitsky I, McGeary SE, & Bartel DP (2013). Beyond secondary structure: Primary-sequence determinants license pri-miRNA hairpins for processing. Cell, 152(4), 844–858. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacolla A, Wang G, & Vasquez KM (2015). New perspectives on DNA and RNA triplexes as effectors of biological activity. PLoS Genetics, 11(12), e1005696. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP (2009). MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell, 136(2), 215–233. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskerville S, & Bartel DP (2005). Microarray profiling of microRNAs reveals frequent coexpression with neighboring miRNAs and host genes. RNA—A Publication of the RNA Society, 11(3), 241–247. 10.1261/rna.7240905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann V, & Winkler J (2014). miRNA-based therapies: Strategies and delivery platforms for oligonucleotide and non-oligonucleotide agents. Future Medicinal Chemistry, 6(17), 1967–1984. 10.4155/fmc.14.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Chung WJ, Willis J, Cuppen E, & Lai EC (2007). Mammalian mirtron genes. Molecular Cell, 28(2), 328–336. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin V, Faucher-Giguere L, Scott M, & Abou-Elela S (2019). The cellular landscape of mid-size noncoding RNA. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA, 10(4), e1530. 10.1002/wrna.1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan CI, Dees EC, Ingram RS, & Tilghman SM (1990). The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 10(1), 28–36. 10.1128/mcb.10.1.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budach S, Heinig M, & Marsico A (2016). Principles of microRNA regulation revealed through modeling microRNA expression quantitative trait loci. Genetics, 203(4), 1629–1640. 10.1534/genetics.116.187153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushati N, & Cohen SM (2007). MicroRNA functions. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 23, 175–205. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, & Rinn JL (2011). Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes & Development, 25(18), 1915–1927. 10.1101/gad.17446611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns J, Ingle JN, Kalari KR, Shepherd LE, Kubo M, Goetz MP, … Wang L (2019). The lncRNA MIR2052HG regulates ERalpha levels and aromatase inhibitor resistance through LMTK3 by recruiting EGR1. Breast Cancer Research, 21(1), 47. 10.1186/s13058-019-1130-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, & Hannon GJ (2010). A dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature, 465(7298), 584–589. 10.1038/nature09092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Yu Y, Li H, Hu Q, Chen X, He Y, … Sun R (2019). Long non-coding RNA PVT1 promotes tumor progression by regulating the miR-143/HK2 axis in gallbladder cancer. Molecular Cancer, 18(1), 33. 10.1186/s12943-019-0947-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Cai J, Wang Q, Wang Y, Liu M, Yang J, … Jiang C (2018). Long noncoding RNA NEAT1, regulated by the EGFR pathway, contributes to Glioblastoma progression through the WNT/beta-catenin pathway by scaffolding EZH2. Clinical Cancer Research, 24(3), 684–695. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Qiu J, Chen B, Lin Y, Chen Y, Xie G, … Jiang D (2018). Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 plays an important role in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by targeting miR-204 and modulating the NF-kappaB pathway. International Immunopharmacology, 59, 252–260. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YG, Satpathy AT, & Chang HY (2017). Gene regulation in the immune system by long noncoding RNAs. Nature Immunology, 18(9), 962–972. 10.1038/ni.3771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes D, Xue H, Taylor DW, Patnode H, Mishima Y, Cheloufi S, … Giraldez AJ (2010). A novel miRNA processing pathway independent of Dicer requires Argonaute2 catalytic activity. Science, 328(5986), 1694–1698. 10.1126/science.1190809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemson CM, Hutchinson JN, Sara SA, Ensminger AW, Fox AH, Chess A, & Lawrence JB (2009). An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Molecular Cell, 33(6), 717–726. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo T, Farina L, Macino G, & Paci P (2015). PVT1: A rising star among oncogenic long noncoding RNAs. BioMed Research International, 2015, 304208–304210. 10.1155/2015/304208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, An X, Li J, Liu Q, & Liu W (2018). LncRNA MIR22HG negatively regulates miR-141–3p to enhance DAPK1 expression and inhibits endometrial carcinoma cells proliferation. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 104, 223–228. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czubak K, Lewandowska MA, Klonowska K, Roszkowski K, Kowalewski J, Figlerowicz M, & Kozlowski P (2015). High copy number variation of cancer-related microRNA genes and frequent amplification of DICER1 and DROSHA in lung cancer. Oncotarget, 6(27), 23399–23416. 10.18632/oncotarget.4351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniunaite K, Dubikaityte M, Gibas P, Bakavicius A, Rimantas Lazutka J, Ulys A, … Jarmalaite S (2017). Clinical significance of miRNA host gene promoter methylation in prostate cancer. Human Molecular Genetics, 26(13), 2451–2461. 10.1093/hmg/ddx138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derderian C, Orunmuyi AT, Olapade-Olaopa EO, & Ogunwobi OO (2019). PVT1 signaling is a mediator of Cancer progression. Frontiers in Oncology, 9, 502. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhir A, Dhir S, Proudfoot NJ, & Jopling CL (2015). Microprocessor mediates transcriptional termination of long noncoding RNA transcripts hosting microRNAs. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 22(4), 319–327. 10.1038/nsmb.2982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Agostino S, Valenti F, Sacconi A, Fontemaggi G, Pallocca M, Pulito C, … Blandino G (2018). Long non-coding MIR205HG depletes Hsa-miR-590–3p leading to unrestrained proliferation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Theranostics, 8(7), 1850–1868. 10.7150/thno.22167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong P, Xiong Y, Yue J, Hanley SJB, Kobayashi N, Todo Y, & Watari H (2018). Long non-coding RNA NEAT1: A novel target for diagnosis and therapy in human tumors. Frontiers in Genetics, 9, 471. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P, Wang L, Sliz P, & Gregory RI (2015). A biogenesis step upstream of microprocessor controls miR-17 approximately 92 expression. Cell, 162(4), 885–899. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q, Hoover AR, Dozmorov I, Raj P, Khan S, Molina E, … van Oers NSC (2019). MIR205HG is a long noncoding RNA that regulates growth hormone and prolactin production in the anterior pituitary. Developmental Cell, 49(4), 618–631 e615. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmrich S, Streltsov A, Schmidt F, Thangapandi VR, Reinhardt D, & Klusmann JH (2014). LincRNAs MONC and MIR100HG act as oncogenes in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Molecular Cancer, 13, 171. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Zhang L, Guo J, Niu Y, Wu Y, Li H, … Zhao Y (2018). NONCODEV5: A comprehensive annotation database for long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research, 46(D1), D308–D314. 10.1093/nar/gkx1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, & Fullwood MJ (2016). Roles, functions, and mechanisms of Long non-coding RNAs in cancer. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 14(1), 42–54. 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farazi TA, Spitzer JI, Morozov P, & Tuschl T (2011). miRNAs in human cancer. The Journal of Pathology, 223(2), 102–115. 10.1002/path.2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Jaskiewicz L, Kolb FA, & Pillai RS (2005). Post-transcriptional gene silencing by siRNAs and miRNAs. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 15(3), 331–341. 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn RA, & Chang HY (2014). Long noncoding RNAs in cell-fate programming and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell, 14(6), 752–761. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynt AS, Greimann JC, Chung WJ, Lima CD, & Lai EC (2010). MicroRNA biogenesis via splicing and exosome-mediated trimming in Drosophila. Molecular Cell, 38(6), 900–907. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AH, & Lamond AI (2010). Paraspeckles. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2(7), a000687. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca GS, Vibranovski MD, & Galante PA (2016). Host gene constraints and genomic context impact the expression and evolution of human microRNAs. Nature Communications, 7, 11438. 10.1038/ncomms11438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira AM, Johnson R, Jungreis I, Loveland J, … Flicek P (2019). GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(D1), D766–D773. 10.1093/nar/gky955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, & Bartel DP (2009). Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Research, 19(1), 92–105. 10.1101/gr.082701.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Dong G, Shi H, Zhang J, Ning Z, Bao X, … Xiong B (2019). LncRNA MIR503HG inhibits cell migration and invasion via miR-103/OLFM4 axis in triple negative breast cancer. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 23(7), 4738–4745. 10.1111/jcmm.14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebert LFR, & MacRae IJ (2019). Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 20(1), 21–37. 10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri-Fard S, & Taheri M (2019). Nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1): A long non-coding RNA with diverse functions in tumorigenesis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 111, 51–59. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel M, Heidrich N, Mader U, Krugel H, & Brantl S (2010). A dual-function sRNA from B. subtilis: SR1 acts as a peptide encoding mRNA on the gapA operon. Molecular Microbiology, 76(4), 990–1009. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovarelli M, Bucci G, Ramos A, Bordo D, Wilusz CJ, Chen CY, … Gherzi R (2014). H19 long noncoding RNA controls the mRNA decay promoting function of KSRP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(47), E5023–E5028. 10.1073/pnas.1415098111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady WM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS, Lee JH, Kim YH, Tsuchiya KD, … Tewari M (2008). Epigenetic silencing of the intronic microRNA hsa-miR-342 and its host gene EVL in colorectal cancer. Oncogene, 27(27), 3880–3888. 10.1038/onc.2008.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, & Shiekhattar R (2004). The microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature, 432(7014), 235–240. 10.1038/nature03120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guil S, & Caceres JF (2007). The multifunctional RNA-binding protein hnRNP A1 is required for processing of miR-18a. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 14(7), 591–596. 10.1038/nsmb1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha M, & Kim VN (2014). Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 15(8), 509–524. 10.1038/nrm3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Nam JW, Heo I, Rhee JK, … Kim VN (2006). Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell, 125(5), 887–901. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinske LC, Galante PA, Kuo WP, & Ohno-Machado L (2010). A potential role for intragenic miRNAs on their hosts’ interactome. BMC Genomics, 11, 533. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T, Yoshikawa R, Harada H, Harada Y, Ishida A, & Yamazaki T (2015). Long noncoding RNA, CCDC26, controls myeloid leukemia cell growth through regulation of KIT expression. Molecular Cancer, 14, 90. 10.1186/s12943-015-0364-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Virnicchi G, Tanigawa A, Naganuma T, Li R, Kimura H, … Pierron G (2014). NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 25(1), 169–183. 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PS, Chung IH, Lin YH, Lin TK, Chen WJ, & Lin KH (2018). The Long non-coding RNA MIR503HG enhances proliferation of human ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(5). 10.3390/ijms19051463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte M (2015). The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nature Medicine, 21(11), 1253–1261. 10.1038/nm.3981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hube F, & Francastel C (2018). Coding and non-coding RNAs, the frontier has never been so blurred. Frontiers in Genetics, 9, 140. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig J, Brunschweiger A, Brummer A, Guennewig B, Mittal N, Kishore S, … Hall J (2015). miR-CLIP capture of a miRNA targetome uncovers a lincRNA H19-miR-106a interaction. Nature Chemical Biology, 11(2), 107–114. 10.1038/nchembio.1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingle JN, Xie F, Ellis MJ, Goss PE, Shepherd LE, Chapman JW, … Wang L (2016). Genetic polymorphisms in the long noncoding RNA MIR2052HG offer a pharmacogenomic basis for the response of breast cancer patients to aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer Research, 76(23), 7012–7023. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadaliha M, Gholamalamdari O, Tang W, Zhang Y, Petracovici A, Hao Q, … Prasanth KV (2018). A natural antisense lncRNA controls breast cancer progression by promoting tumor suppressor gene mRNA stability. PLoS Genetics, 14(11), e1007802. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janas MM, Khaled M, Schubert S, Bernstein JG, Golan D, Veguilla RA, … Novina CD (2011). Feed-forward microprocessing and splicing activities at a microRNA-containing intron. PLoS Genetics, 7(10), e1002330. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z, Song R, Regev A, & Struhl K (2015). Many lncRNAs, 5’UTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. eLife, 4, e08890. 10.7554/eLife.08890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Shao C, Wu QJ, Chen G, Zhou J, Yang B, … Fu XD (2017). NEAT1 scaffolds RNA-binding proteins and the microprocessor to globally enhance pri-miRNA processing. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 24(10), 816–824. 10.1038/nsmb.3455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Wang X, Xie X, Liao Y, Liu N, Liu J, … Peng T (2017). lncRNA DANCR promotes tumor progression and cancer stemness features in osteosarcoma by upregulating AXL via miR-33a-5p inhibition. Cancer Letters, 405, 46–55. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Chen Z, Liu X, & Zhou X (2013). Evaluating the microRNA targeting sites by luciferase reporter gene assay. Methods in Molecular Biology, 936, 117–127. 10.1007/978-1-62703-083-0_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahl G (2009). The dictionary of genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kallen AN, Zhou XB, Xu J, Qiao C, Ma J, Yan L, … Huang Y (2013). The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Molecular Cell, 52(1), 101–112. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X, Kong F, Huang K, Li L, Li Z, Wang X, … Wu X (2019). LncRNA MIR210HG promotes proliferation and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer by upregulating methylation of CACNA2D2 promoter via binding to DNMT1. Oncotargets and Therapy, 12, 3779–3790. 10.2147/OTT.S189468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka N, Fujita M, & Ohno M (2009). Functional association of the microprocessor complex with the spliceosome. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 29(12), 3243–3254. 10.1128/MCB.00360-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keniry A, Oxley D, Monnier P, Kyba M, Dandolo L, Smits G, & Reik W (2012). The H19 lincRNA is a developmental reservoir of miR-675 that suppresses growth and Igf1r. Nature Cell Biology, 14(7), 659–665. 10.1038/ncb2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Nguyen TD, Li S, & Nguyen TA (2018). SRSF3 recruits DROSHA to the basal junction of primary microRNAs. RNA, 24(7), 892–898. 10.1261/rna.065862.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TK, Hemberg M, & Gray JM (2015). Enhancer RNAs: A class of long noncoding RNAs synthesized at enhancers. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(1), a018622. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, & Kim VN (2007). Processing of intronic microRNAs. The EMBO Journal, 26(3), 775–783. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Kitagawa K, Kotake Y, Niida H, & Ohhata T (2013). Cell cycle regulation by long non-coding RNAs. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 70(24), 4785–4794. 10.1007/s00018-013-1423-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong R, Zhang EB, Yin DD, You LH, Xu TP, Chen WM, … Zhang ZH (2015). Long noncoding RNA PVT1 indicates a poor prognosis of gastric cancer and promotes cell proliferation through epigenetically regulating p15 and p16. Molecular Cancer, 14, 82. 10.1186/s12943-015-0355-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp F, & Mendell JT (2018). Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell, 172(3), 393–407. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Birgaoanu M, & Griffiths-Jones S (2019). miRBase: From microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(D1), D155–D162. 10.1093/nar/gky1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SC, Baek SC, Choi YG, Yang J, Lee YS, Woo JS, & Kim VN (2019). Molecular basis for the single-nucleotide precision of primary microRNA processing. Molecular Cell, 73(3), 505, e505–518. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde J, Uszczynska-Ratajczak B, Carbonell S, Perez-Lluch S, Abad A, Davis C, … Johnson R (2017). High-throughput annotation of full-length long noncoding RNAs with capture long-read sequencing. Nature Genetics, 49(12), 1731–1740. 10.1038/ng.3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]