Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Endochondral ossification of the otic capsule is a process that continues postnatally; hence, incomplete endochondral ossification is seen as pericochlear hypoattenuation on temporal bone CT scans of children. We determined the prevalence and extent of this entity in a large series and assessed its relation to age and underlying sensorineural hearing loss.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Initially, temporal bone CTs of 40 children with sensorineural hearing loss were retrospectively assessed and compared with those of a control group scanned for non-sensorineural hearing loss reasons to assess any difference in the prevalence or extent of incomplete endochondral ossification. Then the CT scans of 510 children (age range, 17 days to 17 years) were retrospectively reviewed, and any observed endochondral ossification areas were classified as mild, moderate, or extensive, according to their extent.

RESULTS:

Neither the presence nor degree of incomplete endochondral ossification had any significant correlation with the presence of sensorineural hearing loss (P = .08 and P = .1, respectively). Incomplete endochondral ossification was more frequently seen (62% of cases) than complete ossification. There was no statistically significant correlation between incomplete endochondral ossification and sex (P = .8), but an inverse correlation was found between the presence of incomplete endochondral ossification and increasing age (P < .001). Overall, mild incomplete endochondral ossification was the most frequent involvement pattern (44.4%).

CONCLUSIONS:

The pericochlear hypoattenuation in the otic capsule representing incomplete endochondral ossification is a normal finding in children and can be seen as a marked curvilinear hypoattenuation at younger ages in the absence of any clinical disorder.

CT of the temporal bone is widely used for the evaluation of the anatomic details and diseases of the ear, in both adults and children.1 The accurate interpretation of this study requires both a precise knowledge of the complex temporal bone anatomy and a familiarity with the imaging appearance of various pathologic processes involving this area. It is especially important to be aware of potential developmental variations mimicking disease, such as “pericochlear CT hypoattenuation.”2–5 This hypoattenuation, especially seen in children and most frequently in the region of the fissula ante fenestram (FAF), has been reported to occur in 32%–41% of imaged children without any accompanying symptoms.2,5 The otic capsule (OC) hypoattenuated foci are presumed to be a normal variant due to an incomplete endochondral ossification (iEO) of the OC during its developmental process. Focal bony hypoattenuations in the OC are also seen in pathologic conditions such as otosclerosis and osteogenesis imperfecta, however. Otosclerosis, though rare in young children, is known to have hypoattenuation at this same FAF area as an early and relatively sensitive CT finding.6–11 It is thus crucial for the radiologist reporting temporal bone cases to recognize this variation of a developmental stage and its extent, to prevent unnecessary medical or surgical treatment, especially in cases with equivocal clinical and audiometric findings.

Although a few studies have investigated the presence of OC hypoattenuated foci in temporal bone CT in children, their extent was not specified in any previous study. Furthermore, the relation of the OC hypoattenuation to underlying sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) or a radiologically evident inner ear anomaly has not been thoroughly evaluated, to our knowledge. We thus aimed to determine the prevalence of this entity and its extent in a large group of children and to assess its relation to age and underlying SNHL.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was performed in 2 phases. In the first part, the temporal bone CTs of patients with and without SNHL were compared to assess any difference in the prevalence of incomplete endochondral ossification in these 2 groups. For this purpose, temporal bone CT scans of 40 patients with SNHL and temporal bone CTs of age-compatible patients scanned for reasons other than SNHL were assessed with respect to the presence and extent of hypoattenuated foci of the OC. The images were retrieved from the PACS data base in a randomized manner. The indication for the scan in the control group included auricular atresia in 5 patients, middle ear infection in 18 patients, and conductive hearing loss in 17 patients. None of these patients had evidence of SNHL on their audiologic tests, and they did not have any inner ear abnormality on CT. The children scanned for conductive hearing loss had no clinical or audiologic findings suggestive of otosclerosis. The mean age for the patient group with SNHL was 4.9 ± 3.3 years (range, 17 days to 17 years), while for the control group the mean age was 8.1 ± 4.5 years (range, 10 months to 17 years).

For the second phase of the study, the CT scans of 1020 temporal bones of 510 children (younger than 18 years of age) archived the hospital and radiology data base system of our institution (hospital information system and radiology information system, respectively) between January 2005 and May 2014 were reviewed. The patient ages ranged from 17 days to 17 years (mean age, 5.2 ± 4.3 years; female/male ratio, 254:256). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board. Patient charts and audiologic tests were assessed by an experienced otolaryngologist in selected relevant cases.

Imaging

All CT studies of the temporal bone were performed with thin sections, on the same 4-channel multidetector CT scanner (Somatom Plus 4/Volume Zoom; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The images were obtained by using the pediatric temporal bone protocol, with 0.5-mm collimation, 0.5-mm thickness, 100 mA, and 120 kV(peak). Subsequently, axial reformatted images parallel to the lateral semicircular canal were obtained. Coronal reformatted images were created perpendicular to the axial reformats. Images with extensive motion or implant artifacts (n = 21 children) were excluded from the study. Images without extensive motion or implant artifacts were included in the patient group. Mild motion and/or implant artifacts were observed in 14 temporal bones (1%, 14/1020) but did not prevent the evaluation of the otic capsule.

Image Evaluation

Two neuroradiologists experienced in head and neck imaging (B.O., S.E.S.) retrospectively and simultaneously evaluated the images. Hypoattenuated foci consistent with iEO areas in the OC were defined and classified as mild, moderate, or extensive according to the extent of focal hypoattenuation. Because there were no studies in the literature that had a specific grading system for OC hypoattenuation, we graded it according to the embryologic ossification order from the latest to the earliest. Mild iEO was defined as a focal hypoattenuated area in the FAF region (Fig 1). Moderate iEO was defined as a focal hypoattenuated area extending from the FAF to the anterior aspect of the cochlea (Fig 2). Finally, extensive iEO was defined as a large curvilinear hypoattenuated area extending to the posteromedial aspect of the cochlea in an arc-like pattern (Fig 3).

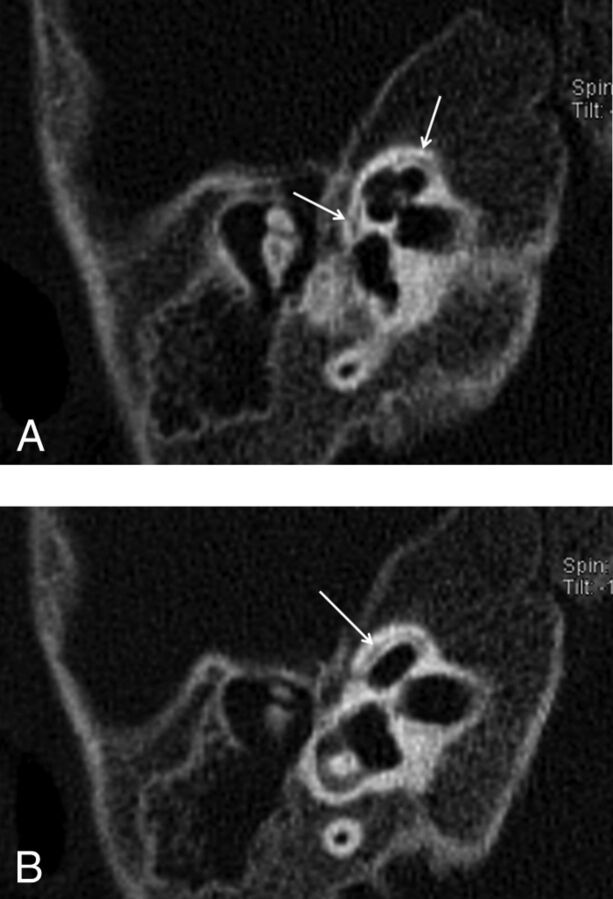

Fig 1.

Reformatted axial CT image of the right (A) and the left (B) temporal bones of a 13-year-old girl with SNHL. Note linear hypoattenuation in the region of the FAF (arrows), consistent with mild incomplete ossification.

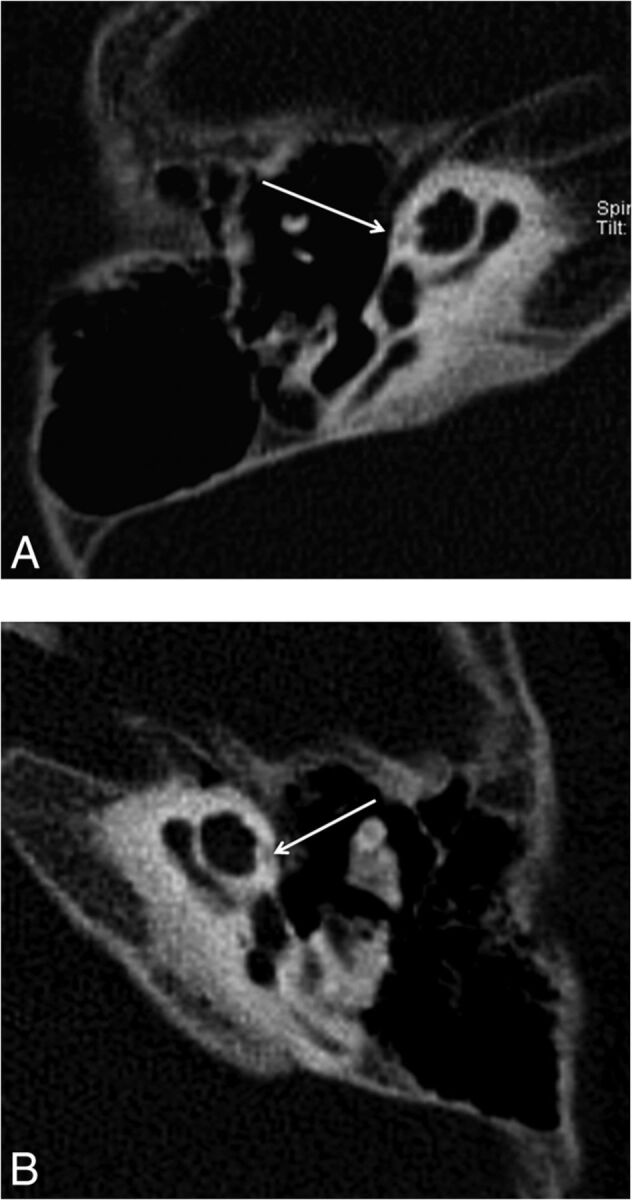

Fig 2.

Reformatted axial CT images of the right (A) and the left (B) temporal bones of a 6-year-old girl with SNHL. Note hypoattenuation in the region of the FAF extending slightly to the anterior aspect of the cochlea (arrows), consistent with moderate incomplete ossification.

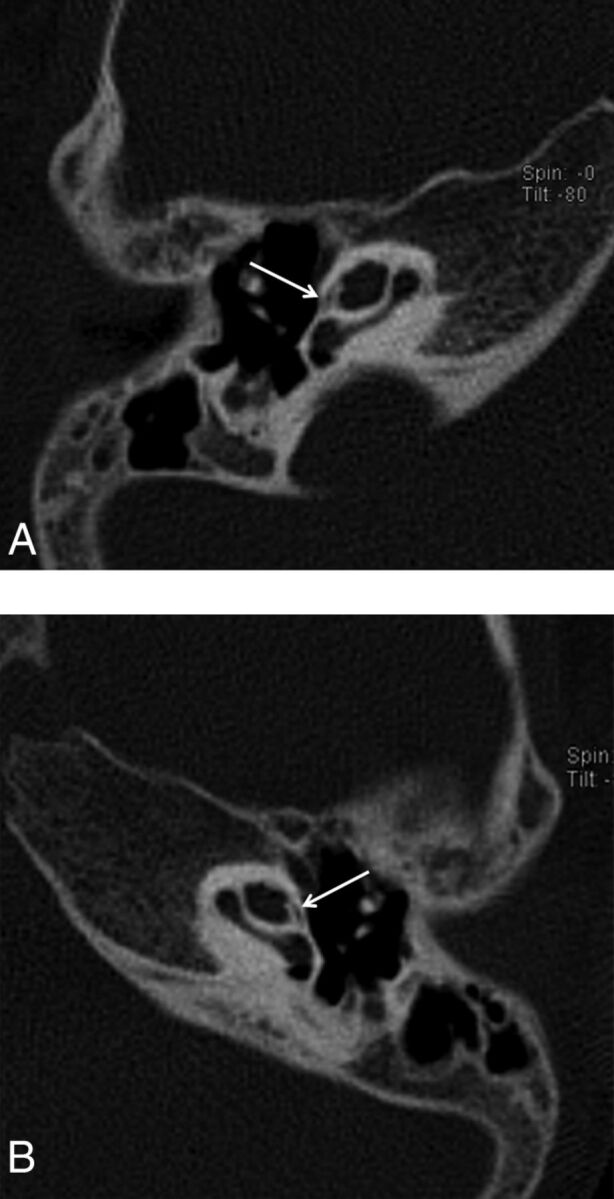

Fig 3.

Axial CT images of the right temporal bone of a 1-year-old boy with SNHL. A hypoattenuated curvilinear line surrounds the cochlea, consistent with extensive incomplete ossification (arrows).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS, Version 15.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, New York). The relationships among EO and sex and SNHL were analyzed by using the χ2 test. Because the ages of patients followed a normal distribution, 1-way analysis of variance was used to determine the relationship between the EO grades and age. Independent t tests were used to analyze the relationships between age and both EO and SNHL. The χ2 test was also used to determine the relationship between the presence and grade of the EO in the patients with SNHL compared with the control group. The level of significance was set at P < .05.

Results

For the cases included in the first phase of the study, iEO was seen in 62% of patients with SNHL and in 57.5% of the control group. Neither the presence nor degree of iEO had any significant correlation with the presence of SNHL by the χ2 test (P = .08 and P = .1, respectively).

For the cases included in the second phase, the temporal bone CT imaging in patients with SNHL revealed normal findings in 846 temporal bones (83%). Various inner ear abnormalities were observed in 174 temporal bones (17%). The most common inner ear abnormality was the enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct (n = 50, 28.7%). In a descending order of frequency, other inner ear abnormalities included incomplete partition abnormality type 2 (31.15%), incomplete partition abnormality type 1 (22.95%), cochlear hypoplasia (19.67%), internal auditory canal stenosis (18.85%), cochlear aperture stenosis (9.8%), isolated vestibular dysplasia (6.56%), common cystic deformity (5.74%), isolated enlarged vestibular aqueduct (4.92%), complete labyrinthine aplasia (3.28%), rudimentary otocyst (1.64%), and cochlear aplasia (0.82%). There was no statistically significant correlation between the presence of iEO and radiologically detected inner ear abnormality (P = .2).

iEO was seen in 62% of all the evaluated cases and thus was more frequent than complete ossification (38% of the cases) in our series. The mean age for the iEO group was 2.8 ± 2.4 years (range, 17 days to 17 years), and for complete ossification, the mean age was 7.9 ± 4.6 years (range, 8 months to 17 years). There was no statistically significant correlation between iEO and sex (P = .8). However, an inverse correlation was found between the presence of iEO and increasing age by an independent t test (P < .001).

In the iEO group (n = 633), mild iEO was the most frequent involvement pattern (n = 453, 71.6%). Moderate iEO was found in 118 temporal bones (18.6%), while extensive iEO was found bilaterally in 62 temporal bones (9.8%). The mean ages for the mild, moderate, and extensive iEO groups were 3.7 ± 3.1 (range, 5 months to 15 years), 2.5 ± 1.9 (range, 4 months to 12 years), and 1.1 ± 0.8 years (range, 17 days to 6 years), respectively (Table). The age range and the mean age of mild and moderate iEO groups were quite similar. However, the mean age showed statistically significant differences between the mild and moderate iEO groups (P = .005). The youngest patient population was seen in the extensive iEO group (mean age, 1.1 ± 0.8 years). Additionally, 80% of patients having extensive iEO were younger than 1 year of age, and 65.5% were younger than 6 months of age. Extensive iEO was thus much more frequent in infants compared with older children. However, a cutoff age limit could not be defined to differentiate the extensive iEO group from mild/moderate iEO groups (P = .2, P = 1, respectively). The charts of cases presenting with extensive iEO were reviewed, but no clinical or audiologic manifestations suggestive of otospongiosis and osteogenesis imperfecta were found (Fig 4).

Frequency and age distribution of the different levels of otic capsule endochondral ossification

| EO of the Otic Capsule | No. of Temporal Bones (%) | Mean Age (yr) (Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Complete | 387 (38%) | 7.9 ± 4.6 (8 months to 17 years) |

| Incomplete | 633 (62%) | 2.8 ± 2.4 (17 days to 15 years) |

| Mild | 453 (71.6%) | 3.7 ± 3.1 (5 months to 15 years) |

| Moderate | 118 (18.6%) | 2.5 ± 1.9 (4 months to 12 years) |

| Extensive | 62 (9.8%) | 1.1 ± 0.8 (17 days to 6 years) |

Note:—EO indicates endochondral ossification.

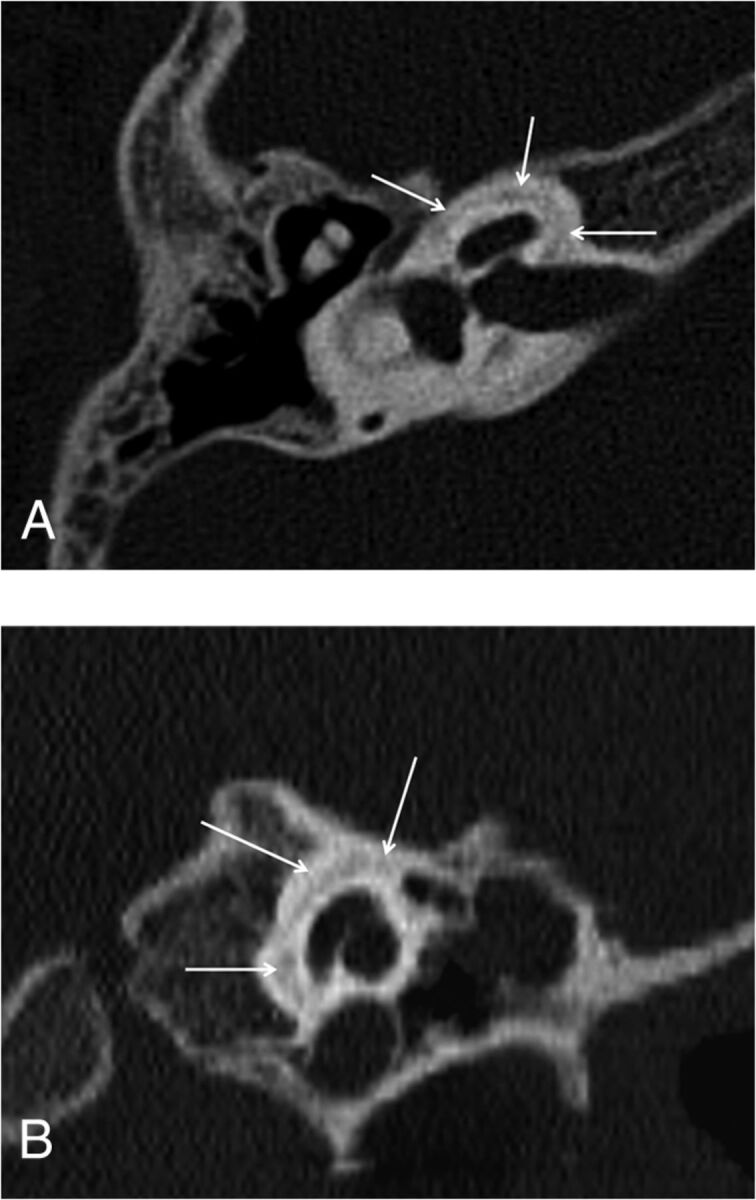

Fig 4.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) CT images of the right temporal bone of a 6-year-old boy with SNHL who had been treated with corticosteroids for 3 years due to congenital adrenogenital syndrome. Hypoattenuation surrounding the cochlea, consistent with extensive incomplete ossification, is again noted (arrows).

The pattern of iEO involvement (defined by the grade) was asymmetric between the 2 ears of the same patient in 37 cases (7.5%). In most patients with asymmetric iEO involvement (23 patients), EO was complete in one ear, while the other ear presented mild iEO. In the remaining 14 patients, the asymmetric ossification pattern was mild iEO in one ear and moderate in the contralateral ear. In 17 of 74 patients presenting with asymmetric EO, various inner ear abnormalities were found. Inner ear structures were radiologically normal in the remaining 57 ears with the asymmetric ossification pattern. The asymmetric pattern did not have a statistically significant correlation with the underlying inner ear abnormality (P = .2). The presence of an asymmetric enchondral ossification pattern showed reverse correlation with age (P = .03).

Discussion

The temporal bone has highly complex anatomy, and its embryonic development is reported to be one of the most complicated examples of cellular morphogenesis in any biologic system. The initial step in the formation of the ear is the differentiation of the otic placode, which will form the membranous labyrinth. Through a complicated embryogenesis influenced by numerous autocrine and paracrine factors, the surrounding mesenchyme undergoes chondrogenesis, which will eventually form the bony capsule that encircles the membranous labyrinth.12–15 The mechanism of ossification of the OC is mainly by EO, with intrachondral bone ossification predominating in some stages.16 Histologically, the ossifying OC has 3 layers: a thin inner (endosteal) layer, a middle layer composed of a combination of endochondral and intrachondral bone, and an outer (periosteal) layer. The endosteal layer of bone surrounding the otic capsule ossifies at midgestation and does not change after birth; the middle layer, however, is partly calcified in the near-term fetus but then is rapidly replaced by bone.4 EO is completed finally in the region of the FAF, which is a cleft between the inner and middle layers just anterior to the oval window.5 Fibrocartilage may persist at the FAF even in adults; this region is also a site of predilection for otosclerosis (probably due to the presence of specific cartilage constituents targeted by autoimmune reactions).17

Because ossification is first completed in the inner and outer layers and the middle layer containing bone marrow is the last portion to ossify, the FAF region, which has mainly a middle layer, might remain as an incompletely ossified area even in adults and can be seen as a focal hypoattenuation on CT images even in adults.5 In our series, CT revealed focal hypoattenuation in the region of the FAF in most children (633 cases, 62%). The incidence in our study is higher than that in previously reported series with incidences in the range of 32%–41%. This difference may be partly due to technical factors because our study acquired very thin sections (the section thickness of the scans in the prior studies were as follows: 0.5–1.5 mm in the study by Pekkola et al,5 0.5–0.75 mm in the study by de Brito et al,3 and this information was not given in the study by Chadwell et al2). The mean age of our study was similar to the one in the series by Pekkola et al5 and thus could not provide an explanation for the difference in incidences (the mean age was not given in the other 2 studies).

In the development of the inner ear, different inner ear structures are known to induce each other. In addition, EO is not completed until the membranous inner ear structures have completed and reached their adult size. One might expect that the EO could be affected by pathologies of the inner ear (radiologically silent or detected). However, we found no correlation between the presence of SNHL and the level of EO. De Brito et al3 compared the incidence of hypoattenuated foci in patients with and without SNHL and similarly found no correlation. We diagnosed radiologic inner ear abnormalities in 174 (17%) of all the imaged temporal bones, but those cases had degrees of EO similar to those in the cases with normal-appearing inner ears. We thus suggest that the presence of hypoattenuated foci in the OC is independent of the membranous and bony labyrinth development.

In this study, the iEO was similar among the 2 sexes but, as expected, had an inverse correlation with age. This finding is in agreement with previously mentioned series reporting that the OC ossification is correlated with the age of the individual rather than the sex but is somewhat controversial due to the established knowledge of delayed bone maturation in males,18 and our results may be because the area of concern is very small and minor differences are difficult to detect. Asymmetric EO among the contralateral ears was found in 74 patients without a sex or age predilection (P = .8 and P = 1, respectively). As suggested in previous studies, inherent variations in the developmental process might play a role in these minor asymmetries.

In a CT study evaluating ossification features of the OC,4 it has been shown that incomplete ossification of the entire middle otic layer in a neonate skull specimen was seen as a hypoattenuated halo surrounding the cochlea (Fig 4 in the article by Moser et al4). This appearance is similar to that in our cases labeled extensive iEO; thus, extensive iEO probably reflects the earliest appearance of a completely nonossified middle layer. In our study, 31 patients had extensive iEO. Patients included in the extensive iEO group were younger in comparison with the 2 other iEO groups, and 65.5% of the patients with extensive iEO were 6 months of age or younger.

The mean age for the mild iEO group was higher (3.7 ± 3.1 years) than that of the moderate and extensive iEO groups. Although the mean ages for different grades of iEO (mild, moderate, and extensive) were numerically close to one another, there was a direct correlation of age with the degree of ossification of the OC. These findings lead us to think that in most cases, extensive iEO subsequently does convert to moderate and mild iEO with increasing age. In a single patient in our series who had subsequent imaging a year later, we found that extensive iEO had upgraded to moderate iEO in the follow-up study the next year. Although it was not the aim of this study, it would be interesting to see, in a separate study, the evolution of the iEO with time for individual patients (eg, with a retrospective data base search of children who had multiple temporal bone studies).

Although the mean age of the patients was significantly different between the mild and moderate iEO groups (P = .005), this significance could not be reached when comparing the mean age values of moderate iEO and extensive iEO groups. Overlapping age ranges between the iEO groups might have influenced these statistical results. However, more important, the small number of patients with extensive iEO and the presence of older children, which has caused an increase in the mean age in the group with extensive iEO, are probably the main reasons for statistical insignificance. The lower number of patients with extensive iEO in our series could be because very small children and infants do not frequently undergo CT imaging and they tend to be imaged preferentially with MR imaging due to radiation concerns.

In the extensive iEO group, only 1 patient (a 6-year-old boy) had a history of corticosteroid administration for 3 years due to congenital adrenogenital syndrome. Except for this 1 case, we did not find any underlying pathologic condition in children with extensive iEO who were older than 1 year of age to explain a delay in ossification, such as vitamin D deficiency or other metabolic abnormalities. Because the patients with extensive iEO in our series did not undergo histopathologic evaluation of their otic capsule, it is still unclear whether the imaging findings are due to an individual variation or are a result of delayed bone maturation. Similarly, an underlying genetic abnormality was not sought but cannot be ruled out.

The small size of the control group is the main limitation of our study. Because SNHL is the prominent type of hearing loss in childhood and for this young age group CT of the temporal bone is mainly undertaken to identify possible inner ear abnormalities, it is difficult to obtain a large control group of patients without SNHL or inner ear abnormalities. Patients with extensive iEO were only evaluated for radiologic mimics such as osteogenesis imperfecta and otosclerosis and were not investigated further for genetic and/or laboratory abnormalities; however, as of today, no significant scientific data suggest a specific underlying cause for delayed/abnormal endochondral ossification besides osteogenesis imperfecta and otosclerosis. Further studies with histopathologic correlation and investigations comparing temporal bone maturation with systemic bone development are necessary to resolve this issue.

Conclusions

The presence of focal hypoattenuation in the OC can be accepted as a normal finding in young children. Mild forms of incomplete endosteal ossification can be seen in children up to 15 years of age and can have asymmetric involvement between the 2 ears of the same individual. At younger ages (especially in the first 6 months of life), excessive hypoattenuation reaching the anterior OC can be seen without any clinical evidence of otosclerosis/osteogenesis imperfecta. This hypoattenuation most likely represents incomplete endochondral ossification, a process that seems to proceed independent of the development of the inner ear.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- FAF

fissula ante fenestram

- iEO

incomplete endochondral ossification

- OC

otic capsule

- SNHL

sensorineural hearing loss

Footnotes

Paper previously presented at: American Society of Neuroradiology Annual Meeting and the Foundation of the ASNR Symposium, April 21–26, 2012; New York, New York.

References

- 1. Krombach GA, Honnef D, Westhofen M, et al. Imaging of congenital anomalies and acquired lesions of the inner ear. Eur Radiol 2008;18:319–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chadwell JB, Halsted MJ, Choo DI, et al. The cochlear cleft. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:21–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Brito P, Metais JP, Lescanne E, et al. Pericochlear hypodensity on CT: normal variant in childhood [in French]. J Radiol 2006;87(6 pt 1):655–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moser T, Veillon F, Sick H, et al. The hypodense focus in the petrous apex: a potential pitfall on multidetector CT imaging of the temporal bone. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:35–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pekkola J, Pitkaranta A, Jappel A, et al. Localized pericochlear hypoattenuating foci at temporal-bone thin-section CT in pediatric patients: nonpathologic differential diagnostic entity? Radiology 2004;230:88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. d'Archambeau O, Parizel PM, Koekelkoren E, et al. CT diagnosis and differential diagnosis of otodystrophic lesions of the temporal bone. Eur J Radiol 1990;11:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lescanne E, Bakhos D, Metais JP, et al. Otosclerosis in children and adolescents: a clinical and CT-scan survey with review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2008;72:147–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mafee MF, Henrikson GC, Deitch RL, et al. Use of CT in stapedial otosclerosis. Radiology 1985;156:709–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mafee MF, Valvassori GE, Deitch RL, et al. Use of CT in the evaluation of cochlear otosclerosis. Radiology 1985;156:703–08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rovsing H. Otosclerosis: fenestral and cochlear. Radiol Clin North Am 1974;12:505–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Swartz JD, Mandell DW, Berman SE, et al. Cochlear otosclerosis (otospongiosis): CT analysis with audiometric correlation. Radiology 1985;155:147–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Groves A. The induction of the otic placode. In: Kelley M, Wu D, Fay RR, eds. Development of the Inner Ear: Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Vol. 26. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:10–42 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kelly M, Wu D. Developmental neurobiology of the ear: current status and future directions. In: Kelly M, Wu D, Fay RR, eds. Development of the Inner Ear: Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Vol. 26. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mansour S, Schoenwolf G. Morphogenesis of the inner ear. In: Kelly M, Wu D, Fay RR, eds. Development of the Inner Ear: Springer Handbook of Auditory Research. Vol. 26. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:43–84 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nemzek WR, Brodie HA, Chong BW, et al. Imaging findings of the developing temporal bone in fetal specimens. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996;17:1467–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sperber GH. Craniofacial Embryology. London: Wright; 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang CC, Yi ZX, Abramson M. Type II collagen-induced otospongiosis-like lesions in rats. Am J Otolaryngol 1986;7:258–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ballabriga A. Morphological and physiological changes during growth: an update. Eur J Clin Nutr 2000;54(suppl 1):S1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]