Using CT or DWI, the authors categorized percentages of insular ribbon infarctions as less or more than 50% and correlated these with clinical outcomes. Only insular ribbon involvement greater than 50% and low NIHSS score at admission correlated with poor outcomes. They concluded that DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% independently predicted poor clinical outcome and can help identify patients with stroke likely to have poor outcome despite small admission DWI lesion volumes.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Large admission DWI infarct volume (>70 mL) is an established marker for poor clinical outcome in acute stroke. Outcome is more variable in patients with small infarcts (<70 mL). Percentage insula ribbon infarct correlates with infarct growth. We hypothesized that percentage insula ribbon infarct can help identify patients with stroke likely to have poor clinical outcome, despite small admission DWI lesion volumes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We analyzed the admission NCCT, CTP, and DWI scans of 55 patients with proximal anterior circulation occlusions on CTA. Percentage insula ribbon infarct (>50%, ≤50%) on DWI, NCCT, CT-CBF, and CT-MTT were recorded. DWI infarct volume, percentage DWI motor strip infarct, NCCT-ASPECTS, and CTA collateral score were also recorded. Statistical analyses were performed to determine accuracy in predicting poor outcome (mRS >2 at 90 days).

RESULTS:

Admission DWI of >70 mL and DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% were among significant univariate imaging markers of poor outcome (P < .001). In the multivariate analysis, DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% (P = .045) and NIHSS score (P < .001) were the only independent predictors of poor outcome. In the subgroup with admission DWI infarct of <70 mL (n = 40), 90-day mRS was significantly worse in those with DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% (n = 9, median mRS = 5, interquartile range = 2–5) compared with those with DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of ≤50% (n = 31, median mRS = 2, interquartile range = 0.25–4, P = .036). In patients with admission DWI infarct of >70 mL, DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct did not have added predictive value for poor outcome (P = .931).

CONCLUSIONS:

DWI–percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% independently predicts poor clinical outcome and can help identify patients with stroke likely to have poor outcome despite small admission DWI lesion volumes.

Multimodality imaging is gaining importance as a prognostic tool in the setting of acute stroke; however, finding a reliable and practical imaging marker that can provide additional prognostic information over the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale alone has been challenging. Current imaging markers that have been shown to be predictive of clinical outcome in acute stroke with proximal anterior circulation occlusions include DWI infarct volume, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score, and “malignant” CTA collateral profile.1

Large admission DWI infarct volume (>70 mL) is one of the more established imaging markers for poor clinical outcome in acute stroke.2,3 DWI lesion volume has been shown to influence response to both intravenous and intra-arterial treatment; specifically, a large pretreatment DWI lesion is recognized as a clinically useful marker for poor treatment response.3,4 Clinical outcome is more variable in patients with small infarcts (<70 mL).3 An imaging marker that can more reliably predict clinical outcome in patients with small DWI infarcts has not been established, to our knowledge. Such a marker could be a useful tool for risk-benefit stratification and patient selection for reperfusion therapy.

One potential imaging marker that could help improve prediction of clinical outcome in small infarcts is percentage insular ribbon infarction (PIRI). Prior studies have suggested that proximal MCA infarcts that involve the insula are associated with infarct growth and unfavorable clinical outcome.5–7 This association is understandable from knowledge of the vascular supply of the insula, which comprises almost exclusively superior and inferior division M2 branches. An infarct from a proximal MCA occlusion that spares the insula may be indicative of good MCA collateral flow, whereas an infarct from a proximal MCA occlusion with insula involvement may be a sign of insufficient MCA collateral flow. Furthermore, the insula is recognized as a functional integration center for autonomic responses, and alterations in blood glucose, blood pressure, myocardial contractility, and body temperature may also contribute to adverse outcome in cerebral ischemia.5,8

The purpose of our study was to determine whether percentage insular ribbon infarct can help identify patients with stroke with proximal vessel occlusions likely to have poor clinical outcome, despite small admission DWI lesion volumes.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We retrospectively identified 200 consecutive patients with acute ischemic stroke admitted during a 2-year period. This study was Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and was approved by our institutional review board. All patients underwent the standard acute stroke imaging algorithm at our institution. We reviewed the clinical and imaging data of this study cohort. Fifty-five patients met the following inclusion criteria: 1) imaging within 9 hours of symptom onset including NCCT, head and neck CTA, CTP with 8-cm shuttle mode anterior circulation coverage, and MR imaging–DWI within 3 hours of CTP; 2) large-vessel occlusion (ICA terminus and/or proximal MCA [M1 or M2], as per the Boston Acute Stroke Imaging Scale9); and 3) modified Rankin Scale score recorded at admission and 3 months after admission. Of the patients excluded, 52 had no proximal occlusion, 41 did not have admission DWI, 21 had a CTP-DWI interval of >3 hours, 13 had posterior circulation strokes, 10 had uninterpretable images, 6 did not have recorded admission and/or 3-month mRS, and 2 had inappropriate location of the CTP acquisition.

Image Acquisition

All imaging was performed in accordance with the standard institutional acute stroke imaging algorithm. CT was performed by using a helical scanner (LightSpeed 64; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin). Noncontrast head CT was acquired in a helical mode (1.25-mm thickness, 120 kV, 250 mAs) and was reformatted at 5-mm intervals. CTA was performed after administration of 80–90 mL of nonionic contrast (iopamidol, Isovue Multipack-370; Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, New Jersey) followed by 40 mL of saline, both at 4 mL/s (1.25-mm thickness, 120 kV, auto mA, 0.5–0.7 s/rotation). CTP used 35 mL of nonionic contrast (Isovue Multipack-370; Bracco Diagnostics) at 7 mL/s followed by 40 mL of saline at 4 mL/s (acquisition time, 90 seconds; 80 kV; 500 mAs maximum), providing sixteen 5-mm thick sections (8-cm coverage) through the anterior circulation. All CTP images were postprocessed with CTP 4D automated software (GE Healthcare). The average total estimated effective radiation dose from the entire CT/CTA/CTP acquisition was approximately 11 mSv.

MR imaging was performed by using a 1.5T Signa scanner (GE Healthcare). Our stroke protocol included a single-shot echo-planar spin-echo DWI sequence with two 180-degree radiofrequency pulses to minimize eddy current warping. Three images per section were acquired at b=0 s/mm2, followed by 25 at b=1000 s/mm2, for 28 images per section. Twenty-three to 27 sections covered the entire brain. Imaging parameters were TR/TE, 5000/80–110 ms; FOV, 22 cm; matrix, 128 × 128 zero-filled to 256 × 256; 5-mm section thickness with a 1-mm gap.

Image Analysis

We analyzed, by visual inspection, the following imaging markers on the admission scans of the 55 study patients: 1) percentage insula ribbon infarct (>50%, ≤50%) on NCCT, DWI, CT-CBF, and CT-MTT; 2) percentage DWI motor strip infarct (less than one-third, one-third to two-thirds, more than two-thirds); and 3) CTA collateral score (0 = absent collaterals in >50% of an M2 territory, 1 = diminished collaterals in >50% of an M2 territory, 2 = diminished collaterals in <50% of an M2 territory, 3 = collaterals equal to those of the contralateral side, 4 = increased collaterals).1 Percentage insula ribbon infarct for each case was determined by visually inspecting the insula on each contiguous imaging section and deciding whether the abnormality as a whole involved more or less than 50% of the total insula. A 50% PIRI binary threshold for total insula was selected because approximately 50% of the insula is supplied by branches from the superior division and 50% is supplied by the inferior division of the MCA. In addition, this was an overall more reproducible and accurate imaging marker in predicting clinical outcome on preliminary analysis, performing better than the 25% PIRI total insula, the 50% PIRI anterior insula, and the two-thirds on 1 section/50% on 2 section techniques used in prior publications.6,7 These imaging markers were independently determined by 2 board-certified radiologists with 1 year and 20 years of dedicated neuroradiology experience. Interpreting radiologists were blinded to all clinical and imaging information except for acute neurologic symptoms. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

In addition, DWI infarct volumes were manually segmented by a board-certified radiologist with 5 years of general and 2 years of dedicated neuroradiology experience and were corrected by an experienced Certificate of Added Qualification–certified neuroradiologist with 20 years' experience, using semiautomated software (Analyze 8.1; AnalyzeDirect, Overland Park, Kansas). NCCT-ASPECTSs were recorded by the same Certificate of Added Qualification–certified neuroradiologist according to standard methodology, rating 10 distinct brain regions for ischemic hypoattenuation or loss of gray-white matter differentiation. Similarly, the interpreting radiologists were blinded to all clinical and imaging information except for acute neurologic symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

Cases were dichotomized into good (mRS 0–2) versus poor (mRS 3–6) clinical outcome. Univariate binary logistic regression was performed on all imaging markers to determine significance in predicting poor outcome. Adjusting for time-to-imaging and treatment assignment, we performed multivariate binary logistic regression with stepwise selection on significant univariate predictors of poor clinical outcome (baseline NIHSS score, DWI-PIRI, DWI infarct volume, CTA collateral score, NCCT-PIRI, and NCCT-ASPECTS). Two multivariate models with and without DWI imaging predictors were analyzed. We compared continuous, ordinal, and discrete variables using the unpaired t test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Fisher exact test, respectively. Interrater agreement for imaging markers was determined by using the κ statistic. MedCalc for Windows software, Version 11.5.1.0 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used to perform statistical analysis. Statistical significance was P < .05.

Results

Patient demographics, treatments, and univariate predictors of poor clinical outcome are listed in the Table. Mean time from symptom onset to CT was 3 hours 48 ± 1 minute 43 seconds. Fourteen patients were imaged at 0–3 hours, 36 at 3–6 hours, and 5 at 6–9 hours. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) time between CT and MR imaging studies was 51 minutes (range, 41–65 minutes).

Admission clinical and imaging variables, stratified by good-versus-poor outcome (3-month mRS 0–2 versus 3–6, respectively)

| Variablea | All Patients | Good Outcome (mRS 0–2) | Poor Outcome (mRS 3–6) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (No.) (%) | 55 | 23 (42) | 32 (58) | – |

| Female sex (No.) (%) | 26 (4) | 12 (52) | 14 (43) | .731 |

| Age (yr) (mean) | 67 ± 15 | 63 ± 17 | 70 ± 13 | .064 |

| Right hemisphere (No.) (%) | 23 (42) | 8 (35) | 15 (47) | .535 |

| Baseline NIHSS (median) (IQR) | 14 (6–18) | 6 (4–11) | 17 (14–20) | <.001 |

| IV treatment (No.) (%) | 18 (33) | 9 (39) | 9 (28) | .392 |

| IA treatment (No.) (%) | 4 (7) | 1 (4) | 3 (9) | .466 |

| Any treatment (IV or IA) (No.) (%) | 10 (18) | 3 (13) | 7 (22) | .395 |

| No IV or IA treatment (No.) (%) | 23 (42) | 10 (43) | 13 (41) | .628 |

| Ictus to DWI (min) (mean) | 286 ± 108 | 277 ± 134 | 291 ± 87 | .68 |

| Ictus to CT perfusion (min) (mean) | 229 ± 107 | 224 ± 140 | 232 ± 79 | .79 |

| DWI volume >70 mL (No.) (%) | 15 (27) | 0 (0) | 15 (27) | <.001 |

| DWI-PIRI >50% (No.) (%) | 22 (40) | 3 (5) | 19 (35) | <.001 |

| NCCT ASPECTS (median) (IQR) | 8 (6–10) | 9 (8–10) | 7 (5–8) | <.001 |

| Collateral score (median) (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 1 (1–2) | .002 |

| Malignant collateral pattern (No.) (%) | 4 (7) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | .131 |

| NCCT-PIRI >50% (No.) (%) | 17 (31) | 2 (4) | 15 (27) | .003 |

| DWI motor strip score, (median) (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1.5) | .010 |

| CT-CBF-PIRI >50% (No.) (%) | 39 (71) | 14 (25) | 25 (45) | .133 |

| CT-MTT-PIRI >50% (No.) (%) | 44 (80) | 17 (31) | 27 (49) | .294 |

Note:—IA indicates intra-arterial.

Results expressed as absolute numbers (%), mean (±SD), or median (IQR).

Continuous, ordinal, and discrete variables compared with the unpaired t test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Fisher exact test, respectively.

Admission NIHSS score was the only significant clinical predictor of poor outcome (P < .001). Admission DWI of >70 mL (P < .001), DWI-PIRI of >50% (P < .001), NCCT-ASPECTS (P < .001), NCCT-PIRI of >50% (P = .003), CTA collateral score (P = .002), and DWI motor strip (P = .01) were significant imaging univariate predictors of poor outcome. PIRI of >50% on CT-CBF and CT-MTT were not significant univariate predictors of poor outcome.

In multivariate analyses, the first binary logistic regression model, with DWI-PIRI of >50%, NIHSS score, DWI of >70-mL threshold, NCCT-ASPECTS, and CTA collateral score as covariates revealed DWI-PIRI of >50% (P = .045) and NIHSS score (P < .001) to be the only independent predictors of poor outcome. Considering that some centers may have limited access to MR imaging in the emergency department, we performed a second binary logistic model with NCCT-PIRI of >50%, NIHSS score, NCCT-ASPECTS, and CTA collateral score as covariates, which revealed the NIHSS score (P < .001) to be the only independent predictor of poor outcome.

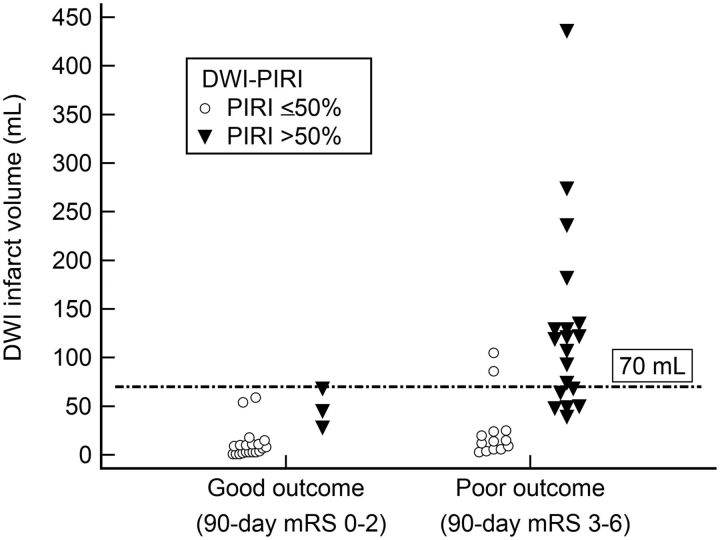

The DWI volume threshold of 70 mL was 100% specific and 47% sensitive for poor outcome (Fig 1). Fourteen of 14 patients with DWI lesion volume of >70 mL had mRS 3–6. When DWI volume was <70 mL, clinical outcome was highly variable; 24/41 patients with DWI lesion volume of <70 mL had good outcome with mRS 0–2 and 17/41 patients had poor outcome with mRS 3–6.

Fig 1.

Scatterplot showing clinical outcome for patients stratified by infarct volume and DWI-PIRI. There was a 100% specific admission 70-mL DWI volume cutoff value for poor outcome.

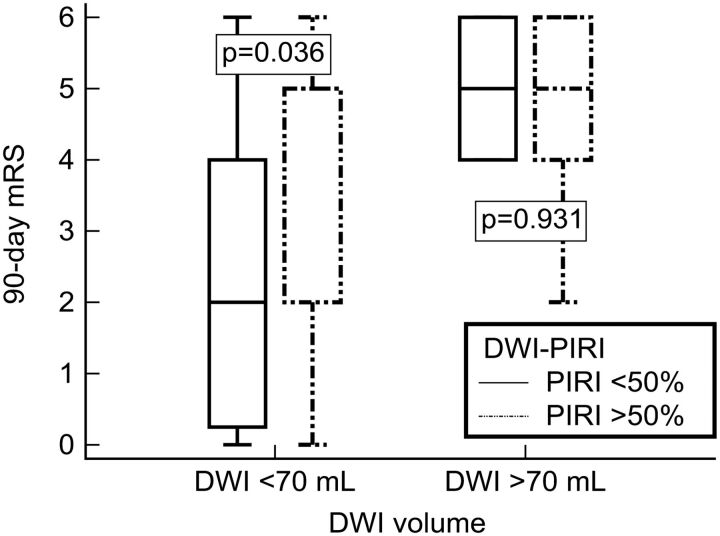

In patients with admission DWI infarct of <70 mL (n = 40), the 90-day mRS score was significantly worse in those with DWI-PIRI of >50% (n = 9, median mRS = 5, IQR = 2–5) compared with those with DWI-PIRI of ≤50% (n = 31, median mRS = 2, IQR = 0.25–4, P = .036) (Figs 2 and 3). Furthermore, 67% of patients with DWI lesion volume of <70 and DWI-PIRI of >50% had poor outcome. In patients with admission DWI infarct of >70 mL, DWI-PIRI did not have added predictive value for poor outcome (P = .931).

Fig 2.

In patients with DWI infarct volumes of <70 mL, 90-day mRS was significantly worse when the DWI-PIRI was >50% compared with a DWI-PIRI of ≤50% (P = .036). In patients with DWI infarct volumes of >70 mL, DWI-PIRI did not have added predictive value for poor outcome (P = .931).

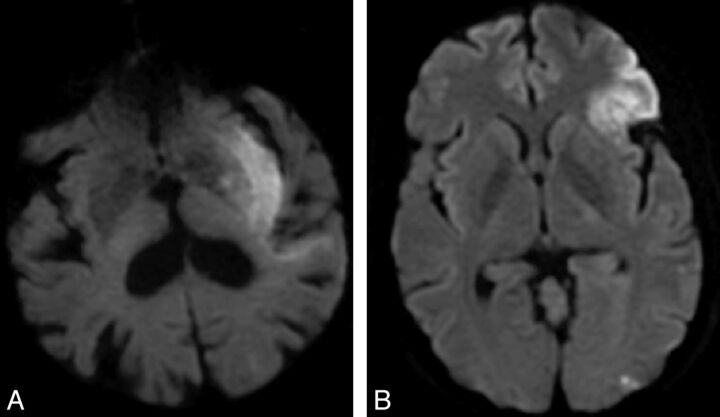

Fig 3.

Sample imaging from 2 patients with ICA terminus occlusions. Patients A and B had similar baseline NIHSS scores (11 and 8), similar small volume infarcts on DWI (50 and 59 mL), the same collateral score (2), the same treatment (IV tPA), but differing degrees of insula involvement. The patient with >50% DWI-PIRI (patient A) had a poor clinical outcome (mRS 5 at 90 days), whereas the patient with ≤50% DWI-PIRI (patient B) had a good clinical outcome (mRS 1 at 90 days).

Interobserver agreement analyses revealed κ values of 0.81 for DWI-PIRI, 0.82 for NCCT-PIRI, 0.74 for DWI motor strip score, 0.69 for CBF-PIRI, 0.77 for MTT-PIRI, and 0.44 for CTA collateral score.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that DWI-PIRI of >50% independently predicts poor clinical outcome and can help identify patients with stroke likely to have poor outcome despite small admission DWI lesion volumes. Consequently, the DWI-PIRI score may help to more accurately weigh the potential risks versus benefits of advanced stroke treatments than assessment by the NIHSS score and DWI lesion volume alone.

These results are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that insula infarcts are predictive of penumbral loss and poor clinical outcome compared with infarcts sparing the insula.5–7,10,11 Of note, diffusion and perfusion MR imaging have been used to demonstrate that infarctions of the insula are associated with an increased percentage of mismatch loss (conversion of potentially viable neighboring penumbra into infarction).5,7 Fink et al6 dichotomized patients with insula infarcts into “major” (equal to or more than two-thirds on 1 section or >50% on ≥2 sections) versus smaller “minor” insula lesions and found major insula infarct involvement to be associated with larger MCA territory infarcts and higher NIHSS scores, indicating more severe clinical deficits. In another study, Christensen et al10 showed significantly worse mRS scores at 3 months in patients with right-sided insula infarcts compared with those with left-sided infarcts or no insula involvement.

Our study further expands on these findings by the following means: 1) demonstrating the added prognostic value of DWI-PIRI of >50% in predicting clinical outcome in patients with small DWI lesion volumes, 2) developing a practical and easily reproducible DWI-PIRI scoring system, 3) applying this PIRI scoring method in a patient population with ICA terminus and/or proximal MCA occlusions, and 4) providing direct comparison of our PIRI scoring method with other important imaging and clinical markers of stroke outcome.

Specifically our results show DWI-PIRI of >50%, DWI infarct volume of >70 mL, NCCT ASPECTS, NIHSS score, CTA collateral score, and DWI motor strip score to be univariate predictors of poor clinical outcome, with DWI-PIRI of >50% and NIHSS score being the only independent predictors of poor outcome. The added predictive value of DWI-PIRI to the NIHSS score makes sense if one considers that the NIHSS is a clinical assessment measuring deficits from the infarct and ischemic penumbra. The NIHSS cannot distinguish whether clinical deficits originate from infarcted tissue or tissue at risk for infarction. The DWI-PIRI score provides a unique visual marker that adds value to the NIHSS by partly delineating the amount of clinical deficit due to infarct and by predicting infarct progression. Thus, the addition of DWI-PIRI may be a useful adjunct to the NIHSS and DWI infarct volume in helping to predict clinical outcome, particularly in patients with small DWI infarct volumes who may have a higher potential for infarct growth.

Our threshold of >50% DWI insula infarct involvement for predicting poor clinical outcome adds to the recent work of Kamalian et al,7 who demonstrated that >25% DWI insula infarct involvement was the strongest predictor of large mismatch loss (infarct growth) in a cohort of patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusions. Our observed larger threshold of >50% insula infarct involvement is likely because we assessed a different outcome measure. While Kamalian et al measured changes in lesion volumes based on follow-up scans, we indirectly assessed loss of insula and other MCA region functions as measured by the 90-day modified Rankin Scale.

The insula has long been an established marker of early MCA stroke12,13 and has been shown to be among the brain regions most vulnerable to ischemia.14 The association between insula infarct involvement and worsened tissue and clinical outcome may be 2-fold: 1) Insula infarcts may serve as a marker for poor collateral flow throughout the greater MCA territory, and 2) infarcts of the insula may lead to autonomic system alterations that may contribute to adverse tissue outcome.

The insula is supplied almost exclusively by M2 segment MCA branches, with a small contribution from M1 insular branches in some individuals.15 The superior MCA division gives rise to branches that supply the anterior insula, whereas the inferior MCA division supplies the posterior insula. The insula is vulnerable to ischemia from proximal occlusion of the M1 MCA segment and the superior and inferior division MCA branches because there is limited possibility of recruiting pial collateral supply from the anterior or posterior cerebral arteries. An infarct due to proximal MCA occlusion that spares the insula but involves the more downstream MCA territory might be indicative of good pial collateral circulation, whereas an MCA occlusion with infarct including the insula can be a sign of insufficient collateral circulation and thus infarct growth.5

Another link between insula infarct and worsened outcome may be related to the role of the insula in modulation of the autonomic nervous system. Clinical and experimental investigations indicate that there is increased sympathetic nervous system activity, including increased plasma catecholamine levels, in insula infarcts.5,16 Some of the effects of sympathetic system activation have been associated with adverse clinical or tissue outcome in cerebral ischemia. For example, an elevated norepinephrine concentration after stroke is a predictor of insula involvement and poor neurologic outcome,16 and likewise poststroke hyperglycemia occurs more often with insular infarcts and is associated with larger infarct size and poor neurologic outcome.5,17 A recent study by Kemmling et al18 found a significant association between the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the setting of right hemispheric peri-insular strokes, an association that is thought to be related to autonomic modulation of the immune system.

The insula is a highly recognizable anatomic structure on cross-sectional imaging due to its distinctive location adjacent to the frontal and temporal operculum, just medial to the Sylvian fissure. Our high interobserver agreement in determining the DWI-PIRI score is in keeping with prior structural MR imaging studies that show high reproducibility for anatomic localization.19

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size, retrospective design, and heterogeneity of treatment. It is noteworthy that the unenhanced CT insula score was not an independent predictor of outcome in the multivariate model, when DWI was excluded and the admission NIHSS score was included. This may be secondary to both shorter time to imaging and lesser sensitivity for infarct detection, compared with DWI. Recanalization status, an established predictor of stroke outcome, was not available for a large number of our patients, thus precluding its entrance into our analysis. Our findings should be validated in a larger prospective study that adjusts for recanalization status.

Conclusions

DWI percentage insula ribbon infarct of >50% predicts poor clinical outcome in acute ischemic stroke and can help identify patients who are likely to have a poor clinical outcome despite small admission DWI lesion volumes. Because it facilitates direct visual estimation of the likelihood of poor outcome, the DWI-PIRI score may help more accurately weigh the potential risks versus benefits of advanced stroke treatments than clinical assessment by the NIHSS and estimation of DWI lesion volume alone. Consideration of DWI insula infarct involvement may be an additional tool for risk-benefit stratification and patient selection for reperfusion therapy.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- IQR

interquartile range

- PIRI

percentage insula ribbon infarct

Footnotes

Disclosures: Michael H. Lev—RELATED: Grant: for Specialized Programs of Translational Research in Acute Stroke, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke,* for Screening Technology and Outcomes Project in Stroke, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke*; UNRELATED: Consultancy: GE Healthcare, Grants/Grants Pending: GE Healthcare. Shervin Kamalian—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: GE Healthcare. *Money paid to the institution.

Abstract previously presented at: Annual Meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, December 1–6, 2013; Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1. Souza LC, Yoo AJ, Chaudhry ZA, et al. Malignant CTA collateral profile is highly specific for large admission DWI infarct core and poor outcome in acute stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:1331–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yoo AJ, Barak ER, Copen WA, et al. Combining acute diffusion-weighted imaging and mean transmit time lesion volumes with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score improves the prediction of acute stroke outcome. Stroke 2010;41:1728–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yoo AJ, Verduzco LA, Schaefer PW, et al. MRI-based selection for intra-arterial stroke therapy: value of pretreatment diffusion-weighted imaging lesion volume in selecting patients with acute stroke who will benefit from early recanalization. Stroke 2009;40:2046–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsons MW, Christensen S, McElduff P, et al. Pretreatment diffusion- and perfusion-MR lesion volumes have a crucial influence on clinical response to stroke thrombolysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30:1214–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ay H, Arsava EM, Koroshetz WJ, et al. Middle cerebral artery infarcts encompassing the insula are more prone to growth. Stroke 2008;39:373–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fink JN, Selim MH, Kumar S, et al. Insular cortex infarction in acute middle cerebral artery territory stroke: predictor of stroke severity and vascular lesion. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1081–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamalian S, Kemmling A, Borgie RC, et al. Admission insular infarction >25% is the strongest predictor of large mismatch loss in proximal middle cerebral artery stroke. Stroke 2013;44:3084–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Augustine JR. Circuitry and functional aspects of the insular lobe in primates including humans. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1996;22:229–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Torres-Mozqueda F, He J, Yeh IB, et al. An acute ischemic stroke classification instrument that includes CT or MR angiography: the Boston Acute Stroke Imaging Scale. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1111–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Christensen H, Boysen G, Christensen AF, et al. Insular lesions, ECG abnormalities, and outcome in acute stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:269–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laowattana S, Zeger SL, Lima JA, et al. Left insular stroke is associated with adverse cardiac outcome. Neurology 2006;66:477–83, discussion 483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Truwit CL, Barkovich AJ, Gean-Marton A, et al. Loss of the insular ribbon: another early CT sign of acute middle cerebral artery infarction. Radiology 1990;176:801–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moulin T, Cattin F, Crepin-Leblond T, et al. Early CT signs in acute middle cerebral artery infarction: predictive value for subsequent infarct locations and outcome. Neurology 1996;47:366–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Payabvash S, Souza LC, Wang Y, et al. Regional ischemic vulnerability of the brain to hypoperfusion: the need for location specific computed tomography perfusion thresholds in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2011;42:1255–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Türe U, Yasargil MG, Al-Mefty O, et al. Arteries of the insula. J Neurosurg 2000;92:676–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sander D, Winbeck K, Klingelhofer J, et al. Prognostic relevance of pathological sympathetic activation after acute thromboembolic stroke. Neurology 2001;57:833–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bruno A, Biller J, Adams HP Jr, et al. Acute blood glucose level and outcome from ischemic stroke: Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Investigators. Neurology 1999;52:280–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kemmling A, Lev MH, Payabvash S, et al. Hospital acquired pneumonia is linked to right hemispheric peri-insular stroke. PLoS One 2013;8:e71141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naidich TP, Kang E, Fatterpekar GM, et al. The insula: anatomic study and MR imaging display at 1.5 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:222–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]