Abstract

Understanding how an adult brain reaches an appropriate size and cell composition from a pool of progenitors that proliferates and differentiates is a key question in Developmental Neurobiology. Not only the control of final size but also, the proper arrangement of cells of different embryonic origins is fundamental in this process. Each neural progenitor has to produce a precise number of sibling cells that establish clones, and all these clones will come together to form the functional adult nervous system. Lineage cell tracing is a complex and challenging process that aims to reconstruct the offspring that arise from a single progenitor cell. This tracing can be achieved through strategies based on genetically modified organisms, using either genetic tracers, transfected viral vectors or DNA constructs, and even single-cell sequencing. Combining different reporter proteins and the use of transgenic mice revolutionized clonal analysis more than a decade ago and now, the availability of novel genome editing tools and single-cell sequencing techniques has vastly improved the capacity of lineage tracing to decipher progenitor potential. This review brings together the strategies used to study cell lineages in the brain and the role they have played in our understanding of the functional clonal relationships among neural cells. In addition, future perspectives regarding the study of cell heterogeneity and the ontogeny of different cell lineages will also be addressed.

Keywords: Clonal analysis, Neural stem cell, Progenitor potential, Cell progeny, Ontogeny, Cell heterogeneity

Introduction

One fundamental issue in Neuroscience is how the different lineages in the brain are established and what contributions sibling cells make to the nervous system and how they influence its behavior. The current belief is that there is large cell heterogeneity in the adult brain, raising the question as to how these different cell types are generated during development. However, a fundamental question is whether this heterogeneity is ontogenically determined and if so, what are the physiological implications of this? Thus, lineage tracing has developed from the need to pursue all the progeny of specific neural progenitor cells (NPCs) to determine how complete neural networks are built and the contribution of specific progenitors to these networks.

Neural stem cells potential and heterogeneity

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are cells that self-renew and that can produce all the lineages present in the adult brain [1]. Thus, the cell diversity in the brain emerges as the progeny of NSCs progress into lineage-restricted NPCs, more committed cell populations with a more limited differentiation and proliferation potential [2]. The transition to a specific lineage and the consequent loss of potential takes place through symmetric or asymmetric cell divisions. Symmetric divisions amplify the pool of progenitors, generating two identical siblings, whereas asymmetric divisions generate two different daughter cells one of which at least will be more committed to a certain lineage (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Lineage specification of stem cells throughout development occurs through symmetric and asymmetric divisions. b Scheme of the different progenitor potentials of the neuroepithelial cells (NECs) that may coexist in the developing brain. Committed progenitor cells can only give rise to one neural cell type, whereas multipotent progenitors can contribute to all lineages. c Graphical representation of the differentiation of NECs to neuroblasts. The gradual maturation of these cells is reflected in the morphological and molecular changes accompanying their lineage transitions. d Scheme of the prospective (pink) and retrospective (blue) reconstruction lineage approaches. Prospective lineage tracing targets specific progenitors to trace their progeny, whereas retrospective analyses reconstruct the lineage tree from the descendants to the progenitor. e Lumping errors are the result of considering non-clonally related cells as part of the same clone, whereas splitting errors take place when sibling cells are considered as independent clones due to methodological shortcomings. NEC neuroepithelial cell, NSC neural stem cell, NPC neural progenitor cell

At early embryonic stages, the principal neural lineages are specified in the neural plate, a defined region of the ectoderm. In parallel, cells of other origins colonize the prospective brain, such as microglia (mesoderm) and blood vessel cells (endoderm). Initially, NSCs known as neuroepithelial cells (NECs) undergo symmetric cell divisions to amplify their pool and prior to generating bipolar radial glial cells (RGCs) [3]. These RGCs produce all the major cell types in the brain and they are often considered the NSCs of the developing brain [4]. RGCs can either proliferate symmetrically to maintain their pool or asymmetrically to generate intermediate progenitor cells (IPCs). RGCs or IPCs will then divide to generate neuroblasts, post-mitotic cells that are committed to generate mature neurons, or glial cells such as oligodendrocytes, astrocytes or NG2 cells [5]. RGCs form a complex cell population that displays region-specific gene expression in the developing nervous system [6]. NSCs are mainly located in the sub-ventricular zone (SVZ), a neurogenic niche that covers different microdomains of the ventricular embryonic walls comprising the pallium, sub-pallium and septum [7]. The neurogenic niche is considered as a heterogeneous pool of cells, with multiple progenitor types displaying either stem cell attributes or more restricted fates [8]. For example, multipotent NSCs that are capable of giving rise to all brain lineages may exist alongside tri- or bi-potent progenitors that have a more restricted potential [9–11]. NPCs that will contribute only one neural cell type could also be present in these neurogenic niches [12, 13] (Fig. 1b). In the brain, cell specification commences with neurogenesis, whereby neuroblasts give rise to the new neurons. Thereafter, astrogenesis occurs and ultimately, oligodendrogenesis commences that continues throughout perinatal stages [14]. This progression is regulated by intrinsic changes in gene expression but also, it is determined by interactions with environmental and developmental cues. Furthermore, the switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis is driven by competition between downstream transcription factors and growth factor signaling [15, 16]. Different patterning genes are responsible for boundary formation, events that can determine the identity and fate of the NPCs in diverse domains along the lining of the ventricular surface [3].

New approaches in single-cell transcriptome technology have provided novel data regarding cell heterogeneity, addressing the varied gene expression in different brain populations. Specifically, a compilation of molecular markers has been described in the neurogenic niche, expressed in either active or quiescent NPCs under physiological conditions and after brain insult [17–19]. In these studies, cells from the SVZ have been identified based on the expression of particular antigenic markers. Thus, the identity and dynamics of NPCs have been assessed by considering the whole population of ventricular progenitors that express a specific combination of different markers. However, cells expressing selected markers but that are isolated from different areas display distinct self-renewal and differentiation capacities, and they have a distinctive gene expression profile [20]. Thus, no single molecular marker can unambiguously define separate populations. Lineage transition between NPCs and their progeny is achieved by gradual cell maturation, and thus, the expression of the same molecular markers in diverse cell types may overlap at distinct moments in their maturation (Fig. 1c). In the adult neurogenic niche of the SVZ, NSCs have classically been defined as GFAP (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein) expressing cells with a particular morphology [21], although this protein is also expressed by the surrounding astrocytes [22]. Furthermore, CD133 (or prominin1) is a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed by the cilia of the adult NSCs in the SVZ [23], and it is also a molecular marker expressed in ependymal cells populating the same surface [24]. Nestin has been considered to be a typical marker to identify NSCs, although it is still expressed in the IPC population [25]. Another molecular marker used to identify embryonic and adult NSC populations is CD24, which is also expressed in some neuroblast populations, albeit at different levels [26]. Thus, cell diversity studies should be based on the potential of single progenitors rather than that of NPCs pools, requiring finer analyses at the individual cell level.

Together, defining NPC populations using specific markers has some limitations, as it is often impossible to precisely define these complex and heterogeneous cell populations solely in this manner. Accordingly, clonal analysis and lineage tracing has become crucial to further understand the biology of NSCs and their lineage progression [27, 28].

The onset of lineage tracing

Due to the large heterogeneity within the neural progenitor pool, clonal analysis is particularly important when studying stem cell biology. This concept arose at the end of the nineteenth century with the studies of Whitman and collaborators on leech embryos [29], and it is still the subject of intense study today. Cell lineage tracing facilitates the definition of ontogeny, fate and cell behavior in specific tissues or organisms. In the brain, lineage tracing allows the cell progeny of a single neural progenitor to be identified and tracked, and the clonal relationships among co-habiting cells to be defined in the adult. Labeling all the progeny of a specific progenitor or cell population may reveal specific patterns of progenitor proliferation, migration and differentiation. Different prospective and retrospective methodologies have been developed to study cell lineages in the brain (Fig. 1d). Prospective lineage tracing strategies require an initial population of interest to be targeted that will be followed over time, whereas retrospective analysis aims to reconstruct lineage trees from the descendants based on a non-bias selection of the progenitors. The principal drawback when designing clonal methods are the potential lumping and splitting errors (Fig. 1e). Lumping errors arise from considering cells generated from different progenitors as part of the same clone. By contrast, cells that are part of the same lineage could be treated as non-sibling cells due to methodological issues, leading to splitting errors.

Some of the first complete lineage tracing studies were achieved by direct microscope observation of lineage progression using either organisms with a small number of cells, or by isolating NPCs and tracking their divisions in vitro [30]. A ground breaking achievement in the field was the tracing of the entire lineage tree of the nematode C. elegans [31] by time-lapse microscopy. However, direct observation in vivo is not usually viable due to the opacity of the tissue or the aim of studying a larger organism. Nevertheless, direct observation of embryonic development in vivo through an intravital window can be combined with different cell labeling approaches, and this has permitted the monitoring, manipulation and live imaging of mouse embryos [32]. The incorporation of non-toxic chromogens into living cells, referred to as vital dyes, was one of the first methods used to visualize cells over time. The principal advantage of fluorescent vital dyes is that they are easily administered in vivo and they do not require post-processing to be visualized. Among the initial fluorescent dyes widely used were the fluorescent retrograde markers like Fast Blue (a cytoplasmic marker) and Diamidino Yellow (a nuclear marker). These dyes not only produced retrograde labeling of groups of cells but they could also be injected simultaneously to detect double labeled cells [33]. In addition, lipophilic carbocyanine fluorescent dyes like DiI and DiO have been used for anterograde and retrograde neuronal tracing in vivo, and in fixed tissue [34, 35], offering a detailed view of the cell’s morphology. The labeling of proliferative cells by incorporating a nucleoside analog like 5-Bromo-2′deoxyuridine (BrdU) can be also used to study cell lineage and fate potential [36, 37] However, a drawback in these approaches is the dilution of the tracer, triggering the consecutive loss of labeling that is most evident in actively proliferating cells [38].

The discovery of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) [39] and of β-galactosidase encoded by the E. coli LacZ gene [40] revolutionized lineage tracing, taking over from the use of vital dyes. Reporter genes encoding these proteins were introduced to target cells by lipofection [41] or electroporation [42], and viral particles carrying these reporters could infect cells, integrating the desired recombinant DNA into the host genome to allow cell tracing [43]. Retroviruses have been used widely to trace cell lineages [44–46]. The reporter genes are introduced via retroviral vectors that integrate into the genome of dividing target cells and they are consequently transferred to all their progeny. The first viral tracing methods focused on targeting a limited number of sparse progenitor cells to ensure that the labeled cells populating the same area would pertain to the same clone. Serial dilution of the viral particles can be used to target fewer isolated progenitors. However, an increment of the number of traceable lineages and a stronger lineage analysis was obtained using retroviral libraries that include DNA barcoding [47]. These barcodes can be read after cell sorting or laser dissection, permitting a reconstruction of the lineages. Nevertheless, the use of retroviral labeling can be compromised by epigenetic silencing and the inability to transfect quiescent or non-mitotic cells [48].

Tracking cells from their progenitors to their final destination and fate has been made possible through the development of some important genetic tools that have made permanent cell labeling feasible. In particular, the Cre-LoxP [49] and Flp-FRT [50] recombination systems represented an important advance to study cell progeny. The incorporation of a tamoxifen-inducible version of this technology in transgenic mouse lines expanded the possibilities of undertaking cellular studies in genetically modified organisms (GMOs) [51]. Transgenic mouse lines that are susceptible to inducible-Cre recombination under the control of specific promoters can drive the expression of a fluorescent reporter (FR) to fate map neural progenitors in vivo [52]. This has been achieved by administering low doses of tamoxifen and depending on the lineage of interest, transgenic mice encoding different FRs under the control of specific promoters have been generated, exhibiting particular advantages and disadvantages [53].

In addition, early lineage tracing studies used chimeric mice generated from tetraparental embryos enabled the origin of many structures in the body to be determined [54]. Moreover, transplanting labeled cells from GMOs into wild type animals has also been used to trace cell lineages [55, 56], although one shortcoming of this approach is that the grafted cells may not behave as they do under physiological conditions [57].

Multicolor lineage tracing

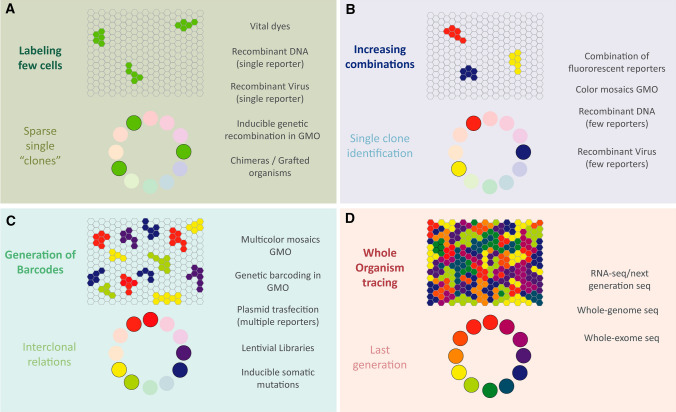

The employment of GMOs and the incremental growth of reporters led to the idea of combining different fluorescent proteins to track sibling cells (Fig. 2). Initially, a few fluorescent variants of GFP were combined to stain neurons individually [58] but undoubtedly, the true revolution in multicolor lineage methods commenced with the appearance of the Brainbow technology [59]. Brainbow transgenic mice undergo stochastic recombination of up to four FRs that are driven by the Cre-LoxP system, giving rise to multicolor mosaics in which single cells can be easily identified. Modified versions of this methodology are still being developed [60, 61] and they produce vivid images, that allow an extremely detailed visualization of the morphologies of individual labeled cells. Hence, this is a very effective method for cell mapping but not for lineage tracing. However, this technology has had a tremendous impact on the field of lineage tracing, leading to a new wave of methods in which the stochastic combination of FRs is used to generate unique barcodes in NSCs that can be inherited by all their progeny. This method was originally designed for mice, although the combinatorial use of fluorescent proteins has been remodeled to fate mapping in Drosophila melanogaster (Flybow, d-Brainbow, Raeppli) [62–64] and Zebrafish (Zebrabow) [65, 66]. The nuclear expression of more than one fluorophore per cell has generated new modifications of the Brainbow-like technique in Drosophila (nBitbow) [67]. Other clonal methods isolate recombination in stochastic cells involving different transgenic lines, such as the mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) [68, 69], and this technology has also been modified to D. melanogaster (twin-spot) [70]. The principal drawback of these techniques, besides the requirement for GMOs, is the small range of combinations to accurately define daughter cells, and the susceptibility to clonal splitting or lumping errors. Moreover, visualizing the fluorescent signal in some of these transgenic mice requires immunostaining [28], an important limitation due to the lack of antibodies to specifically recognize these FRs. Thus, to extend multicolor lineage tracing to different organisms or even to in vitro assays, recombinant viral particles or DNA plasmids have been designed. Recombinant lentiviruses encoding different FRs have been generated to contribute to the multicolor mosaic for lineage tracing (LeGo) [71, 72]. New approaches involve recombinant DNA constructs that encode different FRs, and that can be transfected into the cells of interest, have allowed all the progeny of single cells to be traced (StarTrack, CLONE, MAGIC, iON) [73–76]. To resolve the timing of the birth of each cell within the same clone, lineage progression could be determined post hoc by the expression of a predetermined sequence of fluorophores in sibling cells in Drosophila (CLADES) [77]. These methods are based on transposable elements that are integrated into the genome, allowing the stable inheritance of the same barcode by all cell progeny, and avoiding plasmid loss as a consequence of cell division. The combinatorial use of integrable FRs does not require post-processing to visualize the signals due to the bright and stable expression of these proteins, thereby representing an accessible and convenient technique to use in vivo. Moreover, injection of the reporter proteins in vitro or in vivo facilitates the targeting of progenitor cells at a single-cell level, avoiding the need to produce GMOs. New advances in microscopy have produced progress in multicolor lineage tracing [78], expanding the possibility of performing lineage tracing in any organism and lineage, and enabling studies of cell heterogeneity.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of multicolor lineage methods. Diagram of the most relevant approaches using combinations of fluorescent reporter proteins for fate mapping. The different strategies are represented by a circle for genetically modified organisms like mice, zebrafish or Drosophila. A hexagon shows the strategies based on recombinant viral particles, and the square represents those approaches involving the use of DNA constructs encoding the different fluorescent reporters

Our laboratory has developed a stochastic clonal analysis method called StarTrack, which allows the progeny of single cells to be traced and analyzed thereafter. The StarTrack methodology was an attempt to develop a genetic in vivo lineage-tracing method that could track all the neural progeny of individual GFAP cells [73]. It is based on the transfection of cells (by electroporation) with a combination of recombinant DNAs encoding six different FRs that are expressed in different cell compartments (cytoplasm or cell nucleus). This produces inheritable marks that permit the long-term in vivo tracking of the different neural cells generated during embryonic development to their final fate in the adult brain. Due to the use of an ubiquitous promoter, the UbC-StarTrack methodology enables the progeny of embryonic and postnatal neural progenitors to be tracked in mice, irrespective of their fate [79]. Recently, to specifically track the descendants of NG2 progenitors, the promoter of either the transposase or transposon constructs was adapted accordingly [80, 81]. Novel methods based on vector integration show high efficiency in terms of stable integration and the transmission of unique fingerprints to their descendants, which can be followed through several cell divisions and along different lineages through postnatal or adult stages. Furthermore, these strategies can be extrapolated to perform clonal and functional analyses in different animal models or in vitro assays. The increase in the number of FRs expressed in different compartments augments the number of possible combinations available in these integrable multicolor methods. For example, the use of six different fluorophores in two different cell compartments (e.g., nuclear and cytoplasmic) leads to a total of 4095 possible color codes. In addition, the number of copies of each reporter could be resolved by analyzing the intensity of fluorescence in each cell [79], helping to minimize possible splitting and lumping errors.

In summary, multicolor image-based lineage tracing methods are among the most reliable methods to define lineage trees. By combining them with state-of-the-art approaches like cell type-specific optogenetic manipulations, single-cell transcriptomic analysis, cell ablation, live-cell imaging, patch-clamp recordings, two-photon microscopy, in vivo and brain slice preparations, they may help us to better understand how lineages are derived in the brain. In addition, they provide a more functional readout of the specific characteristics of clonally related cells derived from the same NPC, adding information regarding their spatial relationships.

Single-cell sequencing and CRISPR to address cell lineage tracing

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) provides us with a powerful tool to sequence the whole genome and it opens a window to complete the study of whole organisms, elucidating their genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic and proteomic profiles. NGS contributes to lineage tracing through both whole genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing. It has revealed somatic mutations that accumulate in cells after replication that can be traced to define lineage progression [82]. These analyses focused on individual cells, revealing the intricate cell heterogeneity at the single-cell level. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) is one of the most powerful tools to identify patterns of cell expression and intrinsic molecular profiles. However, single-cell transcriptomic analysis lacks information regarding ontogenic and spatial tracing. Genomic barcoding using viral libraries, followed by the isolation and sequencing of single cells, has facilitated the fate mapping of neural cells, helping to understand their ontogeny and their lineage potential, and complementing classical barcoding methods [83, 84]. Similarly, the combination of classic barcoding techniques and scRNA-seq could help understand the complex biological systems underlying physiological events and pathological conditions.

Several other strategies have been introduced in recent years, including the implementation of CRISPR technology to drive genome editing and DNA targeting (Fig. 3). The CRISPR/Cas9 was used to perform cell lineage tracing, in theory enabling the entire organism to be reconstructed at the single-cell level using RNA or DNA sequencing. MEMOIR (mutagenesis with optical in situ readout) was the first method based on CRISPR technology that produced dynamic cell records and lineage reconstruction, combining barcoded recording elements (scratchpad) altered by CRISPR–Cas9 genome editing and in situ readouts by seq-FISH RNA imaging [85] (Fig. 3a). The limitation of this system is the lower capacity to detect edited mutations relative to those that used scRNA-seq. One of the first studies to implement CRISPR for phylogenetic analyses in mice was MARC1 (mouse for actively recording cells). These mice can accumulate genomic mutations that can be used to reconstruct the lineage tree of cells based on the homing guide RNA (hgRNA) and CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease [86]. In addition, zebrafish has been the animal model used to develop LINNAEUS (Lineage tracing by Nuclease-Activated Editing of Ubiquitous Sequences) [87], in which lineage trees of zebrafish larvae and adult cells were reconstructed by combining multiple genomic mutations and transcriptome profiling (Fig. 3b). However, the first study to infer a large-scale lineage potential was called GESTALT (genome editing of synthetic target array for lineage tracing), revealing lineage relationships during germ layer patterning in zebrafish. GESTALT employed embryos carrying an array of ten different targets that created an inheritable barcode permitting cell lineage trees to be reconstructed [88]. Nevertheless, this system was not able to distinguish the spatial location of different cell types and it was restricted to early developmental studies. Subsequently, scGESTALT was developed to improve this system, combining CRISPR/Cas9 barcode editing for large-scale lineage tracing with cell characterization using transcriptomic analyses [89]. This new approach enabled cell editing to be performed at multiple points and at later developmental stages, and accordingly it has been established as a powerful tool that enables simultaneous lineage tracing and cell sequencing in vivo [90]. These approaches permit the single-cell clonal dynamics and the transcriptomic profile of cells to be studied (Fig. 3c). Importantly, the clonally related cells located in the same area presented similarities in their transcriptomic profile. More recently, a new mouse line has been obtained using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing based on lineage tracing, called CARLIN (CRISPR array repair lineage tracing: [91]). This revolutionary tool can be used to modify and detect DNA sequences in single cells line, and it could even record the history of specific stimuli, including the lineage related effects of exposure to external stimuli, stress or pathogens. One of the advantages of CARLIN is the inducible activity of Cas9 to generate barcodes at embryonic and adult stages. In conclusion, several models of CRISPR/Cas9 barcoding have shown this is a powerful tool to study fate mapping. However, cell loss or weak RNA expression are among the technical problems encountered when using these methods [92]. Nevertheless, the evolution of CRISPR-Cas9 technology along the new sequencing approaches offers very useful approaches to define fate maps in complex organisms.

Fig. 3.

Timeline of the use of CRISPR/Cas9 for lineage tracing. a In situ mutagenesis involved the accumulation of multiple integration target sites (called barcoded scratchpads) visualized by smFISH. This strategy is a good tool to address the lineage dynamics of a cell population. b In vivo lineage mapping using CRISPR/Cas9 is based on multiple integration/deletion at a target site that allows the lineage trees of the different cells to be reconstructed taking into account their genomic tags (yellow cassettes). c Going further, the inducible Cas9 activity (blue circle) and the incorporation of transcriptomic analysis improves these mouse models, enabling cell lineages and fate mapping to be analyzed at the single-cell level

Insights into the lineage tracing of neural cells from clonal methodology

Several methods have been proposed to examine lineage progression in different biological models in vivo or in vitro. However, their use to determine the relationships of lineages usually requires an arduous analysis. Some approaches for lineage tracing in the brain focus on the sparse labeling of cell clones to ensure the lineage connection among cells that are situated intimately in the brain (Fig. 4a). The injection of diluted viral particles to trace a minimal number of progenitors facilitates the study of the integration of neural clones into different cortical systems [93–95]. Moreover, administering low doses of tamoxifen to inducible Cre-LoxP GMOs favors the characterization of NSC potential [96]. Random Cre-LoxP recombination in sparse progenitor cells during development reveals a common origin of pyramidal neurons and astrocytes [97]. However, these methods have some drawbacks, such as the ambiguous labeling of single NPCs, the impossibility of tracing lineages that undergo diverse migratory pathways and the difficulty for inter-clonal studies. Moreover, the independent basal recombinase activity of inducible Cre lines may interfere with such tamoxifen-based lineage tracing methods [98].

Fig. 4.

Diagram of the different techniques and their improvements based on advances in lineage tracing. a The first lineage analyses were done by random targeting of progenitors in a manner that attempted to ensure the distant labeling of clones. b The incorporation of more than one reporter increased the number of combinations and improved the single-cell clone identity. c The assignment of unique fingerprints to targeted progenitors enabled sibling cells to be identified and their relationships due to the generation of a specific and stable barcode in the cells. d However, the new tools generated to decipher genomic information in an entire organism enable a wealth of important information to be drawn that helps to reconstruct the lineage trees of cells and their sibling connections

Other clonal methods rely on the recombination of few fluorophores for lineage tracing (Fig. 4b), such as mosaic analysis with dual markers that have been used to determine important features of NPC potential and lineage progression in vivo [27, 99, 100]. These approaches help characterize sibling cells at a single-cell level, although only a few codes are generated for unequivocal cell identification and sparse labeling is still required.

More recently, the use of fingerprints to accurately target a single NPC and that can be inherited by their entire progeny has revolutionized the field (Fig. 4c). With these methods a larger number of clones can be assessed, allowing inter- and intra-clonal relationships to be studied, as well as identifying clonal relationships within long-distance migratory cell populations, such as adult generated interneurons [11]. Progenitor barcoding can be achieved by expressing multiple FRs, retroviral libraries or with genetic tags, such as those assembled by the CRISPR-Cas9 or Polilox system [101]. The huge improvement in sequencing technologies and genome editing tools over recent years has enriched the lineage tracing field. These techniques enable phylogenetic lineage trees to be created and linked to transcriptomic information at a single-cell level. The developing central nervous system (CNS) contains many spatially segregated germinal zones, with progenitors that generate distinct cell types. The fate of embryonic progenitors lining either the ventricular surface or the ependymal layer of the developing brain can be traced, and post-natal or adult NPCs in the brain can be also included in the lineage tracing analysis. Clonal methods have demonstrated that these progenitors may be committed to a specific cell lineage or that they may give rise to more lineages. RGCs are considered the major progenitor cell type throughout the CNS. However, new sub-types of NPCs occupy the SVZ, such as apical or basal RGCs, or apical and subapical IPCs [102]. Lineage tracing has shown that RGCs produce glial cells through IPCs or astrocytes by direct transformation [103, 104]. In addition, embryonic RGCs give rise to sibling ependymal cells and adult NSCs that remain in the lateral ventricles [105]. Postnatal NPCs have varied multipotentiality, which differs from that of restricted progenitors specified to only generate a determined lineage, or of bi-potent NPCs that generate sibling cells of two different lineages [11].

Single-cell analyses has provided huge advantages when studying cell heterogeneity and cell dynamics in NSC populations. Transcriptomic approaches have recently shed new light on lineage progression and progenitor potential, and single-cell transcriptomic analysis has revealed important information about cell identity and the distinct expression patterns under different conditions that could be crucial to fine-tune lineage tracing approaches. Transcriptomic analyses have helped classify cells in terms of their specific transcriptomic expression. Several studies have shown the diversification of transcriptional profiles within neuronal [106, 107], astroglial [108, 109] and oligodendroglial populations [110, 111]. Recent approaches using in situ transcriptomic analyses reflect the strong specification and regionalized distribution of astrocytes within the pallial cortex, diverging from the classic six neuronal layered patterns [112]. In addition, bulk RNA-seq has provided important information about gene expression and the molecular differences between cells populating neocortical layers [113]. Furthermore, pseudotemporal alignment of the transcriptomic profiles of developing cerebral organoids gave insight into the maturation and differentiation stages associated with cell-type specification [114]. The regional identity of specific neuronal progenitors has also been described for glial lineages, where progenitors in different domains produce glial cells restricted to a specific region [13, 115], with broad variability in terms of their spatial and clonal organization [116]. Thus, it becomes crucial to determine how embryonic development influences cell fate heterogeneity.

In addition, deep genome sequencing has made it possible to trace the lineage of every single cell in a given organism (Fig. 4d). DNA replication that occurs before cell division produces somatic mutations that do not have phenotypic effects. However, these somatic DNA mutations accumulate in daughter cells and they provide important information that could be useful to reconstruct lineage trees [117, 118].

Lineage tracing techniques can also be applied in pathological situations to address the heterogeneity in terms of therapeutic responses or the different implications according to ontogeny. In this regard, clonal responses have been described in the progression of squamous carcinomas [119], sarcomas [120] and breast cancers [121]. In the CNS, glioblastoma cells engage in clonal communication based on cell–cell contact [122]. Alternatively, clonal expansion of the astrocyte lineage was evident following brain disease or insult, as seen for Huntington’s disease [123], brain injury [124] or multiple sclerosis [125]. This clonal response could be explained by preferential connectivity of sibling astrocytes relative to their neighboring cells [126]. Therefore, fate mapping and cell fate potential mapping could provide important information about lineage trees and evolution, yet it could also shed light on important therapeutic issues or even, on the possible reprogramming of cells. One challenging issue will be to compile and compare all the lineage tracing data obtained through different clonal methodologies to obtain an overview of how lineages evolve [127]. All the emerging data, along with the improved molecular techniques and the developments in big data analysis, can overcome the current limitations to understand the tremendous heterogeneity among cell lineages.

In conclusion, DNA barcoding strategies and sequencing resources could help to consolidate cell lineage reconstructions and contribute to our understanding of cell dynamics, clonal expansion, and the behavior of specific cell lineages in normal conditions and disease. Moreover, this type of analysis may produce important advances in understanding the molecular events underlying lineage specification and the sculpting of progenitor potential.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research Grants from MICINN (PID2019-105218RB-I00), MINECO (BFU2016-75207-R) and Fundación Ramón Areces (Ref. CIVP9A5928).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science (80-) 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:112–117. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowitch DH, Kriegstein AR. Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial–cell specification. Nature. 2010;468:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nature09611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo C, Eckler MJ, McKenna WL, et al. Fezf2 expression identifies a multipotent progenitor for neocortical projection neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Neuron. 2013;80:1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Götz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kriegstein AR, Götz M. Radial glia diversity: a matter of cell fate. Glia. 2003;43:37–43. doi: 10.1002/glia.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azim K, Fiorelli R, Zweifel S, et al. 3-Dimensional examination of the adult mouse subventricular zone reveals lineage-specific microdomains. PLoS ONE. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco SJ, Müller U. Shaping our minds: stem and progenitor cell diversity in the mammalian neocortex. Neuron. 2013;77:19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-Álvarez G, Daclin M, Shihavuddin A, et al. Adult neural stem cells and multiciliated ependymal cells share a common lineage regulated by the geminin family members. Neuron. 2019;102:159–172.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmigiani E, Leto K, Rolando C, et al. Heterogeneity and bipotency of astroglial-like cerebellar progenitors along the interneuron and glial lineages. J Neurosci. 2015;35:7388–7402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueres-Oñate M, Sánchez-Villalón M, Sánchez-González R, López-Mascaraque L. Lineage tracing and cell potential of postnatal single progenitor cells in vivo. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;13:700–712. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortega F, Gascón S, Masserdotti G, et al. Oligodendrogliogenic and neurogenic adult subependymal zone neural stem cells constitute distinct lineages and exhibit differential responsiveness to Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:602–613. doi: 10.1038/ncb2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Marqués J, López-Mascaraque L. Clonal mapping of astrocytes in the olfactory bulb and rostral migratory stream. Cereb Cortex. 2016 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauvageot C, Stiles D. Molecular mechanisms controlling cortical gliogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martynoga B, Drechsel D, Guillemot F, et al. Molecular control of neurogenesis: a view from the mammalian cerebral cortex molecular control of neurogenesis: aview from the mammalian cerebral cortex. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:1–14. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Codega P, Silva-Vargas V, Paul A, et al. Prospective identification and purification of quiescent adult neural stem cells from their in vivo niche. Neuron. 2014;82:545–559. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beckervordersandforth R, Tripathi P, Ninkovic J, et al. In vivo fate mapping and expression analysis reveals molecular hallmarks of prospectively isolated adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llorens-Bobadilla E, Zhao S, Baser A, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals a population of dormant neural stem cells that become activated upon brain injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfenninger CV, Steinhoff C, Hertwig F, Nuber UA. Prospectively isolated CD133/CD24-positive ependymal cells from the adult spinal cord and lateral ventricle wall differ in their long-term in vitro self-renewal and in vivo gene expression. Glia. 2011;59:68–81. doi: 10.1002/glia.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imura T, Kornblum HI, Sofroniew MV. The predominant neural stem cell isolated from postnatal and adult forebrain but not early embryonic forebrain expresses GFAP. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2824–2832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02824.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nolte C, Matyash M, Pivneva T, et al. GFAP promoter-controlled EGFP-expressing transgenic mice: a tool to visualize astrocytes and astrogliosis in living brain tissue. Glia. 2001;33:72–86. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(20010101)33:1<72::AID-GLIA1007>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, et al. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coskun V, Wu H, Blanchi B, et al. CD133+ neural stem cells in the ependyma of mammalian postnatal forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1026–1031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gengatharan A, Bammann RR, Saghatelyan A. The role of astrocytes in the generation, migration, and integration of new neurons in the adult olfactory bulb. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruszak J, Ludwig W, Blak A, et al. CD15, CD24, and CD29 define a surface biomarker code for neural lineage differentiation of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2928–2940. doi: 10.1002/stem.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao P, Postiglione MP, Krieger TG, et al. Deterministic progenitor behavior and unitary production of neurons in the neocortex. Cell. 2014;159:775–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calzolari F, Michel J, Baumgart EV, et al. Fast clonal expansion and limited neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult subependymal zone. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:490–492. doi: 10.1038/nn.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitman C. A contribution to the history of germ layers in clepsine. J Morphol. 1887;1:105–182. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1050010107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Temple S. Division and differentiation of isolated CNS blast cells in microculture. Nature. 1989;340:471–473. doi: 10.1038/340471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Q, Cohen MA, Alsina FC, et al. Intravital imaging of mouse embryos. Science (80-) 2020;368:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.aba0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keizer K, Kuypers HGJM, Huisman AM, Dann O. Diamidino yellow dihydrochloride (DY·2HCl); a new fluorescent retrograde neuronal tracer, which migrates only very slowly out of the cell. Exp Brain Res. 1983;51:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00237193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honig MG, Hume RI. Fluorescent carbocyanine dyes allow living neurons of identified origin to be studied in long-term cultures. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:171–187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honig MG, Hume RI. Dil and DiO: versatile fluorescent dyes for neuronal labelling and pathway tracing. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12:333–341. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornack DR, Rakic P. The generation, migration, and differentiation of olfactory neurons in the adult primate brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4752–4757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081074998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould E, Vail N, Wagers M, Gross CG. Adult-generated hippocampal and neocortical neurons in macaques have a transient existence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10910–10917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181354698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Figueres-Oñate M, García-Marqués J, Pedraza M, et al. Spatiotemporal analyses of neural lineages after embryonic and postnatal progenitor targeting combining different reporters. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, et al. Green fluorescent protein as a marker gene expression. Science (80-) 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Son JH, Min N, Joh TH. Early ontogeny of catecholaminergic cell lineage in brain and peripheral neurons monitored by tyrosine hydroxylase-lacZ transgene. Mol Brain Res. 1996;36:300–308. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(95)00255-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holt CE, Garlick N, Cornel E. Lipofection of cDNAs in the embryonic vertebrate central nervous system. Neuron. 1990;4:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90095-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itasaki N, Bel-Vialar S, Krumlauf R. “Shocking” developments in chick embryology: electroporation and in ovo gene expression. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E203–E207. doi: 10.1038/70231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luskin MB, Pearlman AL, Sanes JR. Cell lineage in the cerebral cortex of the mouse studied in vivo and in vitro with a Recombinant Retrovirus. Neuron. 1988;1:635–647. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levison SW, Chuang C, Abramson BJ, Goldman JE. The migrational patterns and developmental fates of glial precursors in the rat subventricular zone are temporally regulated. Development. 1993;119:611–622. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noctor SC, Flint AC, Weissman TA, et al. Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature. 2001;409:714–720. doi: 10.1038/35055553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zerlin M, Milosevic A, Goldman JE. Glial progenitors of the neonatal subventricular zone differentiate asynchronously, leading to spatial dispersion of glial clones and to the persistence of immature glia in the adult mammalian CNS. Dev Biol. 2004;270:200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Golden JA, Fields-Berry SC, Cepko CL. Construction and characterization of a highly complex retroviral library for lineage analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5704–5708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petit A, Legué E, Nicolas J. Methods in clonal analysis and applications. Reprod nutr Dev. 2005;45:321–339. doi: 10.1051/rnd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauer B. Functional expression of the cre-lox site-specific recombination system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2087–2096. doi: 10.1128/MCB.7.6.2087.Updated. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Golic KG, Lindquist S. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the drosophila genome. Cell. 1989;59:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feil R, Wagner J, Metzger D, Chambon P. Regulation of Cre recombinase activity by mutated estrogen receptor ligand-binding domains. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:752–757. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhaliwal J, Lagace DC. Visualization and genetic manipulation of adult neurogenesis using transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1025–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lacar B, Young SZ, Platel J-C, Bordey A. Imaging and recording subventricular zone progenitor cells in live tissue of postnatal mice. Front Neurosci. 2010;4:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le Douarin N. The Nogent Institute–50 years of embryology. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:85–103. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041952nl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watt FM, Jensen KB. Epidermal stem cell diversity and quiescence. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:260–267. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, et al. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cai D, Cohen KB, Luo T, et al. Improved tools for the Brainbow toolbox. Nat Methods. 2013;10:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hadjieconomou D, Rotkopf S, Alexandre C, et al. Flybow: genetic multicolor cell labeling for neural circuit analysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2011;8:260–266. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hampel S, Chung P, McKellar CE, et al. Drosophila Brainbow: a recombinase-based fluorescence labeling technique to subdivide neural expression patterns. Nat Methods. 2011;8:253–259. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanca O, Caussinus E, Denes AS, et al. Raeppli: a whole-tissue labeling tool for live imaging of Drosophila development. Development. 2014;141:472–480. doi: 10.1242/dev.102913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pan YA, Livet J, Sanes JR, et al. Multicolor brainbow imaging in Zebrafish. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;6:1–8. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pan YA, Freundlich T, Weissman TA, et al. Zebrabow: multispectral cell labeling for cell tracing and lineage analysis in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:2835–2846. doi: 10.1242/dev.094631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Veling MW, Li Y, Veling MT, et al. Identification of neuronal lineages in the drosophila peripheral nervous system with a “Digital” multi-spectral lineage tracing system. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3303–3312.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, et al. Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hippenmeyer S, Johnson RL, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals cell-type-specific paternal growth dominance. Cell Rep. 2013;3:960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Griffin R, Sustar A, Bonvin M, et al. The twin spot generator for differential Drosophila lineage analysis. Nat Methods. 2009;6:600–602. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weber K, Bartsch U, Stocking C, Fehse B. A multicolor panel of novel lentiviral “gene ontology” (LeGO) vectors for functional gene analysis. Mol Ther. 2008;16:698–706. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weber K, Thomaschewski M, Warlich M, et al. RGB marking facilitates multicolor clonal cell tracking. Nat Med. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nm.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.García-Marqués J, López-Mascaraque L. Clonal identity determines astrocyte cortical heterogeneity. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1463–1472. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.García-Moreno F, Vasistha NA, Begbie J, Molnár Z. CLoNe is a new method to target single progenitors and study their progeny in mouse and chick. Development. 2014;141:1589–1598. doi: 10.1242/dev.105254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Loulier K, Barry R, Mahou P, et al. Multiplex cell and lineage tracking with combinatorial labels. Neuron. 2014;81:505–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumamoto T, Maurinot F, Barry-Martinet R, et al. Direct readout of neural stem cell transgenesis with an integration-coupled gene expression switch. Neuron. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia-Marques J, Espinosa-medina I, Ku K, et al. A programmable sequence of reporters for lineage analysis. Nat Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abdeladim L, Matho KS, Clavreul S, et al. Multicolor multiscale brain imaging with chromatic multiphoton serial microscopy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09552-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Figueres-Oñate M, García-Marqués J, López-Mascaraque L. UbC-StarTrack, a clonal method to target the entire progeny of individual progenitors. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33896. doi: 10.1038/srep33896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sánchez-González R, Bribián A, López-Mascaraque L. Cell fate potential of NG2 progenitors. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66753-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sánchez-González R, Figueres-Oñate M, Ojalvo-Sanz AC, López-Mascaraque L. Cell progeny in the olfactory bulb after targeting specific progenitors with different UbC-startrack approaches. Genes (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/genes11030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shapiro E, Biezuner T, Linnarsson S. Single-cell sequencing-based technologies will revolutionize whole-organism science. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:618–630. doi: 10.1038/nrg3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fuentealba LC, Rompani SB, Parraguez JI, et al. Embryonic origin of postnatal neural stem cells. Cell. 2015;161:1644–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mayer C, Jaglin XH, Cobbs LV, et al. Clonally Related forebrain interneurons disperse broadly across both functional areas and structural boundaries. Neuron. 2015;87:989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frieda KL, Linton JM, Hormoz S, et al. Synthetic recording and in situ readout of lineage information in single cells. Nature. 2017;541:107–111. doi: 10.1038/nature20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalhor R, Kalhor K, Mejia L, et al. Developmental barcoding of whole mouse via homing CRISPR. Science (80-) 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aat9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spanjaard B, Hu B, Mitic N, et al. Simultaneous lineage tracing and cell-type identification using CrIsPr-Cas9-induced genetic scars. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:469–473. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McKenna A, Findlay GM, Gagnon JA, et al. Whole-organism lineage tracing by combinatorial and cumulative genome editing. Science (80-) 2016 doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Raj B, Wagner DE, McKenna A, et al. Simultaneous single-cell profiling of lineages and cell types in the vertebrate brain. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:442–450. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chan MM, Smith ZD, Grosswendt S, et al. Molecular recording of mammalian embryogenesis. Nature. 2019;570:77–82. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1184-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bowling S, Sritharan D, Osorio FG, et al. An engineered CRISPR-Cas9 mouse line for simultaneous readout of lineage histories and gene expression profiles in single cells. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Espinosa-Medina I, Garcia-Marques J, Cepko C, Lee T. High-throughput dense reconstruction of cell lineages. Open Biol. 2019 doi: 10.1098/rsob.190229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torii M, Hashimoto-Torii K, Levitt P, Rakic P. Integration of neuronal clones in the radial cortical columns by EphA and ephrin-A signalling. Nature. 2009;461:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature08362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown KN, Chen S, Han Z, et al. Clonal production and organization of inhibitory interneurons in the neocortex. Science. 2011;334:480–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1208884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li Y, Lu H, Cheng P, et al. Clonally related visual cortical neurons show similar stimulus feature selectivity. Nature. 2012;486:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonaguidi MA, Wheeler MA, Shapiro JS, et al. In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell. 2011;145:1142–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Magavi S, Friedmann D, Banks G, et al. Coincident generation of pyramidal neurons and protoplasmic astrocytes in neocortical columns. J Neurosci. 2012;32:4762–4772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3560-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Álvarez-Aznar A, Martínez-Corral I, Daubel N, et al. Tamoxifen-independent recombination of reporter genes limits lineage tracing and mosaic analysis using CreERT2 lines. Transgenic Res. 2020;29:53–68. doi: 10.1007/s11248-019-00177-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beattie R, Postiglione MP, Burnett LE, et al. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals distinct sequential functions of Lgl1 in neural stem cells. Neuron. 2017;94:517–533.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mihalas AB, Hevner RF. Clonal analysis reveals laminar fate multipotency and daughter cell apoptosis of mouse cortical intermediate progenitors. Dev. 2018 doi: 10.1242/dev.164335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pei W, Feyerabend TB, Rössler J, et al. Polylox barcoding reveals haematopoietic stem cell fates realized in vivo. Nature. 2017;548:456–460. doi: 10.1038/nature23653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De Juan RC, Borrell V. Coevolution of radial glial cells and the cerebral cortex. Glia. 2015;63:1303–1319. doi: 10.1002/glia.22827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang Y, Liu G, Guo T, et al. Cortical neural stem cell lineage progression is regulated by extrinsic signaling molecule sonic hedgehog. Cell Rep. 2020;30:4490–4504.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Redmond SA, Figueres-Oñate M, Obernier K, et al. Development of ependymal and postnatal neural stem cells and their origin from a common embryonic progenitor. Cell Rep. 2019;27:429–441.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lake BB, Ai R, Kaeser GE, et al. Neuronal subtypes and diversity revealed by single-nucleus RNA sequencing of the human brain. Science (80-) 2016;352:1586–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Loo L, Simon JM, Xing L, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of mouse neocortical development. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morel L, Men Y, Chiang MSR, et al. Intracortical astrocyte subpopulations defined by astrocyte reporter Mice in the adult brain. Glia. 2019;67:171–181. doi: 10.1002/glia.23545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Batiuk MY, Martirosyan A, Wahis J, et al. Identification of region-specific astrocyte subtypes at single cell resolution. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14198-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Marques S, van Bruggen D, Vanichkina DP, et al. Transcriptional convergence of oligodendrocyte lineage progenitors during development. Dev Cell. 2018;46:504–517.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Marques S, Zeisel A, Codeluppi S, et al. Oligodendrocyte heterogeneity in the mouse juvenile and adult central nervous system. Science (80-) 2016;352:1326–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bayraktar OA, Bartels T, Holmqvist S, et al. Astrocyte layers in the mammalian cerebral cortex revealed by a single-cell in situ transcriptomic map. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:500–509. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0602-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Belgard TG, Marques AC, Oliver PL, et al. A transcriptomic atlas of mouse neocortical layers. Neuron. 2011;71:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kanton S, Boyle MJ, He Z, et al. Organoid single-cell genomic atlas uncovers human-specific features of brain development. Nature. 2019;574(7778):418–422. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bayraktar OA, Fuentealba LC, Alvarez-Buylla A, Rowitch DH. Astrocyte development and heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Clavreul S, Abdeladim L, Hernández-Garzón E, et al. Cortical astrocytes develop in a plastic manner at both clonal and cellular levels. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12791-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Salipante SJ, Horwitz MS. Phylogenetic fate mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5448–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601265103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wasserstrom A, Adar R, Shefer G, et al. Reconstruction of cell lineage trees in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Reeves MQ, Kandyba E, Harris S, et al. Multicolour lineage tracing reveals clonal dynamics of squamous carcinoma evolution from initiation to metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:699–709. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tang YJ, Huang J, Tsushima H, et al. Tracing tumor evolution in sarcoma reveals clonal origin of advanced metastasis. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2837–2850.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Martín-Pardillos A, Valls Chiva Á, Bande Vargas G, et al. The role of clonal communication and heterogeneity in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1–26. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5883-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Davis JB, Krishna SS, Abi Jomaa R, et al. A new model isolates glioblastoma clonal interactions and reveals unexpected modes for regulating motility, proliferation, and drug resistance. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53850-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nato G, Caramello A, Trova S, et al. Striatal astrocytes produce neuroblasts in an excitotoxic model of Huntington’s disease. Development. 2015;142:840–845. doi: 10.1242/dev.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Martín-López E, García-Marques J, Núñez-Llaves R, López-Mascaraque L. Clonal astrocytic response to cortical injury. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bribian A, Pérez-Cerdá F, Matute C, López-Mascaraque L. Clonal glial response in a multiple sclerosis mouse model. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gutiérrez Y, García-Marques J, Liu X, et al. Sibling astrocytes share preferential coupling via gap junctions. Glia. 2019;67:1852–1858. doi: 10.1002/glia.23662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Picco N, Hippenmeyer S, Rodarte J, et al. A mathematical insight into cell labelling experiments for clonal analysis. J Anat. 2019;235:687–696. doi: 10.1111/joa.13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]