Abstract

Obesity is the most crucial phenotype in metabolic syndrome (MetS), and waist circumference (WC) and body mass index (BMI) are two common indexes to define obesity. It is an accepted fact that genetic and environmental interaction influence obesity and MetS. Microsatellites are a subcategory of tandem repeats with a length of 1 to 10 nucleotides. Tandem repeats make up repetitive genomic regions. Differences in the number of tandem repeats or their variation (alleles) result in microsatellite polymorphisms. Thus, we attempted to find microsatellite variation associated with WC and BMI in a family-based study. Twelve microsatellite markers were selected to investigate possible genes or chromosomal regions in 91 families with at least one affected MetS. The cut-off values for BMI and WC were considered 25 kg/m2 and 90 cm, respectively. In all members of the families, the strongest association was observed between the marker D11S1304 (allele 1) with both WC and BMI, independently, by the biallelic model in the family-based association test analysis (P < 0.05). Besides, when we compared high- and low-level groups in members with MetS, the markers D8S1743 and D11S1304 (allele 1) showed a strong association with WC (P = 0.0080) and BMI (P = 0.0074), respectively. When the simultaneous detection of the high WC and MetS status was used as a trait, the strongest association was observed with the marker D8S1743 (P = 0.0034). Moreover, when BMI with the high MetS status was used as a trait, the strongest association was observed with the marker D8S1743 (allele 4) (P = 0.0034). The obtained results showed a relationship between obesity and MetS with markers on the selected regions on chromosomes 8 and 11, and to a lesser degree, on chromosome 12.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Genetics

Introduction

As a multiple-component condition, metabolic syndrome (MetS) can be called a multiplex cardiovascular risk factor. Insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity, in particular central obesity, are known as MetS1,2. The prevalence of obesity in Iranian men and women is 21% and 38.6%, respectively4. Thus, obesity is the most critical factor in the high prevalence of MetS in Iran3. It is accepted that this syndrome results from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors. Moreover, genetic variants underlying metabolic traits have been identified at several loci in Iranian populations5–12. Identifying new chromosomal loci through association studies can help discover new genes responsible for obesity.

The genome-wide analysis has recently identified genetic variants in association with waist circumference (WC) and BMI13,14. These studies found some chromosomal regions such as 8(q22.1-q24.3) containing VPS13B gene15–22, 11(q23.3-q25) containing APOA5, ZPR1, and BUD13 genes23–28, 12(q13.12-q15) containing FAIM2 gene18,29–32, and 16(q23.3-q24.3) containing MAF gene31–33 with high LOD scores concerning BMI and WC (Table 1). Even some genetic variations were reported concerning MetS in the Japanese population34. We attempted to evaluate the effect of variation in the selected regions on obesity in MetS.

Table 1.

Essential genes in the selected chromosomal region.

| Region | Closest gene(s) | Phenotype | Proposed molecular or cellular function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8q22.2 | VPS13B | Abnormal fat storage, obesity, Cohen syndrome | Glycosylation flaws and dysfunction of Golgi | 21,22 |

| 11q23.3 | APOA5 | BMI/metabolic traits | The increased risk of MetS and its components, especially elevated TG and low HDL-C levels | 27,28 |

| 11q23.3 | ZPR1(ZNF259), BUD13 | Serum lipid level elevated TG level | Insulin sensitivity and obesity | 27 |

| 12q13.12 | FAIM2 | BMI | Adipocyte apoptosis | 31,32 |

| 16q23.2 | MAF | BMI | Transcription factor involved in adipogenesis and insulin–glucagon regulation | 31,32 |

Since obesity is an essential component in MetS in Iranian patients, this study aimed to replicate the linkage and association of some chromosomal regions previously reported to be involved in obesity-related factors such as WC and BMI in Iranian families with MetS.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

This study included a total of 490 members of 91 families. Of this number, 122 (24.4%) had MetS, 143 (28.1%) had WC ≥ 90 cm, and 138 (27.2%) suffered from BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. The demographic and biochemical characteristics of all the studied subjects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The demographic and biochemical parameters of participants in the study.

| Characteristic | Total |

|---|---|

| N a = 508 | |

| Age (years) | 36.6 ± 19.1 b |

| Male/female (n) | 247/261 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 5.47 |

| Risk factors for the metabolic syndromes | |

| Waist circumference (Cm) | |

| Women | 84.2 ± 15.4 |

| Men | 90.4 ± 15.4 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 95.1 ± 27.3 |

| Elevated blood pressure (mmHg) | |

| Systolic | 114 ± 20.5 |

| Diastolic | 71.1 ± 10.8 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dl) | 143 ± 89.1 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 185 ± 40.8 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | |

| Women | 47.5 ± 11.7 |

| Men | 40.6 ± 9.56 |

aThe number of subjects in each group.

bMean ± standard deviation.

FBAT analysis

The biallelic model results in the family-based association test (FBAT) analysis for high and low WC and BMI levels in all the family members are provided in Table 3. The strongest association was independent with the marker D11S1304 (allele 1) for WC and BMI (Z = 2.124, P = 0.0337, and Z = 2.253, P = 0.0253, respectively). Although, after correcting the p-value for multiple testing (Bonferroni’s correction), this marker did not last as a significant marker (P = 0.069). Moreover, the multiallelic analysis did not reveal the association with this marker (P = 0.086).

Table 3.

The biallelic model results in the FBAT analysis of high waist circumferences and high BMI.

| Biallelic model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | High waist | High BMI | |||||

| Name | Allele a | Frequency | Z b | P | Frequency | Z | P |

| D8S1132 | 3 | 0.187 | 1.82 | 0.0687 | – | – | – |

| D8S1132 | 18 | 0.066 | –1.893 | 0.0583 | – | – | – |

| D8S1743 | 4 | 0.331 | 1.739 | 0.0821 | 0.331 | 1.879 | 0.0602 |

| D8S1743 | 5 | – | – | – | 0.09 | − 2 | 0.0455 |

| D8S1743 | 12 | 0.016 | − 1.667 | 0.0956 | – | – | – |

| D11S934 | 2 | 0.013 | − 2.236 | 0.0253 | 0.013 | − 2.236 | 0.0253 |

| D11S1304 | 1 | 0.363 | 2.124 | 0.0337 | 0.363 | 2.253 | 0.0243 |

| D11S1304 | 2 | 0.231 | − 1.695 | 0.0901 | – | – | – |

| D12S96 | 4 | 0.042 | − 2.714 | 0.0067 | 0.042 | − 1.941 | 0.0522 |

| D12S329 | 2 | 0.078 | − 2.711 | 0.0067 | 0.078 | − 2.064 | 0.0390 |

| D12S329 | 5 | 0.065 | − 2 | 0.0455 | – | – | – |

| D16S2624 | 1 | – | – | – | 0.185 | − 1.729 | 0.0839 |

| D16S2624 | 2 | 0.316 | 1.81 | 0.0704 | – | – | – |

| D16S3096 | 15 | – | – | – | 0.016 | − 1.89 | 0.0588 |

aAllele name according to the number of repeats.

bValue of the Z test of association.

The association results of WC, the BMI level, and the MetS status in the FBAT analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

The association results of waist circumference, BMI level, and MetS status in the FBAT analysis.

| Marker | Allele a | Waist | BMI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Low waist/high waist)/MetS status | MetS status/waist circumference | (Low BMI /high BMI)/MetS status | MetS status/BMI | ||||||||||||

| Frequency | Z b | P c | Frequency | Z | P | Waistd | Frequency | Z | P | Frequency | Z | P | BMI | ||

| D8S1132 | 17 | 0.064 | 2.153 | 0.0313 | 0.064 | 2.251 | 0.0244 | 85.9 ± 15.6 | 0.064 | 2.243 | 0.0249 | 0.064 | 2.351 | 0.0528 | 25.8 ± 5.97 |

| D8S1779 | 3 | 0.289 | 2.047 | 0.0407 | – | – | – | – | 0.289 | 2.174 | 0.0297 | – | – | – | – |

| D8S1743 | 4 | 0.331 | 2.651 | 0.0080 | 0.331 | 2.931 | 0.0034 | 87.2 ± 15.2 | 0.331 | 2.599 | 0.0093 | 0.331 | 2.842 | 0.0024 | 25.9 ± 5.50 |

| D8S1743 | 7 | 0.026 | − 2.097 | 0.0360 | – | – | – | – | 0.026 | − 2.140 | 0.0324 | – | – | – | – |

| D8S1743 | 13 | 0.016 | − 2.130 | 0.0331 | 0.016 | − 2.165 | 0.0304 | 85.5 ± 14.7 | 0.016 | − 2.100 | 0.0357 | 0.016 | − 2.105 | 0.0450 | 26.3 ± 6.12 |

| D11S1998 | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.013 | − 1.970 | 0.0490 | – | – | – | – |

| D11S934 | 1 | 0.254 | 2.092 | 0.0365 | 0.254 | 1.963 | 0.0496 | 86.1 ± 15.8 | – | – | – | 0.254 | 1.998 | 0.0482 | 25.7 ± 5.53 |

| D11S1304 | 1 | 0.363 | 2.583 | 0.0098 | 0.363 | 2.849 | 0.0044 | 87.9 ± 15.2 | 0.363 | 2.679 | 0.0074 | 0.363 | 2.640 | 0.0025 | 26.4 ± 5.53 |

| D11S1304 | 6 | 0.023 | − 2.934 | 0.0034 | 0.023 | − 2.828 | 0.0047 | 87.8 ± 15.8 | 0.023 | − 2.950 | 0.0032 | 0.023 | − 2.750 | 0.0032 | 26.1 ± 5.21 |

| D12S329 | 1 | 0.035 | − 2.238 | 0.0252 | 0.035 | − 1.995 | 0.0461 | 94.8 ± 14.1 | 0.035 | − 2.330 | 0.0200 | 0.035 | − 1.932 | 0.0532 | 28.7 ± 5.64 |

| D16S2624 | 1 | – | – | – | 0.185 | − 2.083 | 0.0372 | 86.9 ± 14.2 | – | – | – | 0.185 | − 2.148 | 0.0408 | 25.7 ± 5.36 |

| D16S2624 | 2 | 0.316 | 2.370 | 0.0178 | 0.316 | 2.395 | 0.0166 | 87.2 ± 15.1 | 0.316 | 2.404 | 0.0162 | 0.316 | 2.652 | 0.0252 | 25.9 ± 5.25 |

aAllele name according to the number of repeats.

bValue of the Z test of association.

cIn bold, significant p-values after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (global p < 0.05).

The strongest association was observed with the marker D8S1743 for high and low WC in individuals with MetS (Z = 2.651, P = 0.0080). When the simultaneous detection of the high WC and MetS status was investigated, the marker D8S1743 (Z = 2.931, P = 0.0034) had the strongest association. Furthermore, after correcting the p-value for multiple testing (Bonferroni’s correction), there were significant associations with the marker D11S1304 (allele 6) in high and low WC with the MetS status group (P = 0.0405) and with the markers D8S1743 (allele 4) (P = 0.0342), D11S1304 (allele 1) (P = 0.0432), and D11S1304 (allele 6) (P = 0.0351) in WC with the MetS status group.

Besides, the highest association was observed to be with the marker D11S1304 (allele 1) for high and low BMI in individuals with MetS (Z = 2.679, P = 0.0074). When the simultaneous occurrence of high BMI with the MetS status was used as a trait, the strongest association was observed with the marker D8S1743 (allele 4) (Z = 2.931, P = 0.0034). After correcting the p-value for multiple testing (Bonferroni’s correction), there were significant associations with the marker D11S1304 (allele 6) in high and low BMI with the MetS status group (P = 0.0351) and with the markers D8S1743 (allele 4) (P = 0.0254), D11S1304 (allele 1) (P = 0.362), and D11S1304 (allele 6) (P = 0.0381) in BMI with the MetS status group. These results suggested an association with regions on chromosomes 8 and 11, and to a lesser degree, on chromosome 12.

Linkage analysis

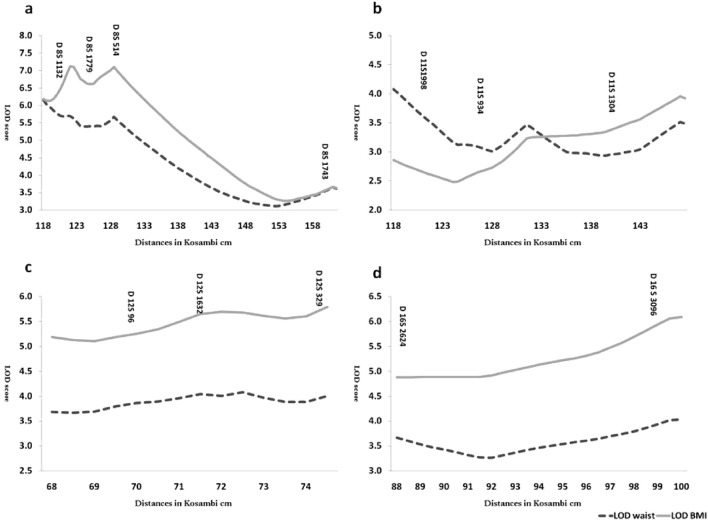

Nonparametric linkage analysis (NPL) performed by Merlin software yielded no significant result for any of the chromosomal regions. The highest NPL score (on the LOD scale) was 1.2 for WC and 1.62 for BMI for the marker D8S514. This result might be explained by the fact that many families are not informative for the studied markers (since the maximal attainable LOD was 1.55). However, if only families with positive nonparametric LOD scores and added LODs were considered, different results would be obtained (Fig. 1). In this figure, 37 families for Chr8, 36 families for Chr11, 31 families for Chr12, and 38 families for Chr16 contributed. LOD scores were above the significance threshold (> 3) for all the markers in all the regions.

Figure 1.

The pooled LOD score for families with the positive score: (A) chromosome 8, (B) chromosome 11, (C) chromosome 12, and (D) chromosome 16.

A parametric analysis was performed under both dominant and recessive analyses (with 80% prevalence and 0.01 disease gene frequency). Although no significant LOD score was found in any of the chromosomal regions, very informative families for the linkage under both modes of inheritance were identified (Table 5). For example, the family 12,422 had the LOD score > 1 for the marker on chromosome 12 (LOD 1.12 for D12S329) based on WC and BMI as a trait. Similar patterns were observed for the family 30,250 with the same marker in groups with WC affection by the 1.01 LOD score. The family 21,030 was identified as being informative and had the linkage under both dominant and recessive models to regions on chromosomes 8 (LOD > 0.7) (Table 5). When the LOD scores of families with positive values were added together, we obtained a global LOD score of about 7.1 for 8q22-24. The pooled LOD score for positive families reached 2.5 for chromosome 11.

Table 5.

The parametric linkage analysis results under both dominant and recessive analyses.

| Region | Model | BMI | Waist | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Position | Microsatellite | LOD score | Family | Position | Microsatellite | LOD score | ||

| 8q22-24 | Dominant | 21,030 | 128.9 | D8S514 | 0.6964 | 10,608 | 128.9 | D8S514 | 0.8597 |

| Recessive | – | – | – | – | 21,030 | 128.9 | D8S514 | 0.6615 | |

| Dominant | 12,622 | 128.9 | D8S514 | 0.7067 | 20,868 | 128.9 | D8S514 | 0.7268 | |

| Dominant | 21,030 | 122.6 | D8S1779 | 0.8527 | 10,608 | 122.6 | D8S1779 | 0.884 | |

| Recessive | – | – | – | – | 21,030 | 122.6 | D8S1779 | 0.7124 | |

| Dominant | 31,563 | 161.5 | D8S1743 | 0.6286 | 20,868 | 117.9 | D8S1132 | 0.7618 | |

| Dominant | 21,030 | 117.9 | D8S1132 | 0.7137 | 30,615 | 117.9 | D8S1132 | 0.6642 | |

| 11q23-25 | Dominant | 20,232 | 131.7 | D11S934 | 0.874 | 20,232 | 131.7 | D11S934 | 0.874 |

| Dominant | 12,422 | 131.7 | D11S934 | 0.8998 | 12,422 | 131.7 | D11S934 | 0.8998 | |

| 12q13-15 | Dominant | 21,464 | 67.16 | D12S96 | 0.7709 | 21,464 | 67.16 | D12S96 | 0.7709 |

| Dominant | 31,682 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 0.6042 | 31,682 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 0.9192 | |

| Dominant | 10,501 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 0.6258 | 11,983 | 67.16 | D12S96 | 0.7424 | |

| Dominant | 12,422 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 1.1242 | 12,422 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 1.1242 | |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 30,250 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 1.0115 | |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 22,305 | 74.58 | D12S329 | 0.7287 | |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 11,983 | 71.61 | D12S1632 | 0.7307 | |

| 16q23-24 | Dominant | 20,232 | 97.3 | D16S3096 | 0.9302 | 20,232 | 97.3 | D16S3096 | 0.9302 |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 31,682 | 97.3 | D16S3096 | 0.9336 | |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 32,189 | 97.3 | D16S3096 | 0.8304 | |

| Dominant | 31,682 | 86 | D16S2624 | 0.6052 | 31,682 | 86 | D16S2624 | 0.9338 | |

| Dominant | 33,372 | 86 | D16S2624 | 0.6716 | 20,868 | 86 | D16S2624 | 0.9906 | |

| Dominant | – | – | – | – | 32,189 | 86 | D16S2624 | 0.7007 | |

Bold families have high LOD scores in both traits.

Discussion

Obesity is the most critical component of MetS in the Iranian population. Thus, four chromosomal regions in 91 families with MetS and high WC and BMI patterns were selected to study the genetic cause of these problems. The genetic transmissions of 12 microsatellite markers were studied, and association analysis was carried out. The FBAT generated nominal support for the allelic association in D8S1743 and D11S1304 in biallelic mode. The linkage analysis yielded no significant results for any of the chromosomal regions. Still, when we considered only families with positive nonparametric LOD scores and added their LODs, LOD scores were above the three thresholds for all the markers in all the regions. These results are in good agreement with the FBAT results since our results are in agreement with previous findings.

The biallelic FBAT analysis results showed that the 12q13-15 chromosomal region with the D12S329 microsatellite marker had a significant association with WC and BMI variation; however, this relation disappeared after Bonferroni correction. This marker has the highest LOD score in Iranian families under the dominant model, whereas the marker D8S1743 was the most significant under the recessive model and in association tests. Norris et al.18 found a high LOD score in this region for the waist to hip ratio. After using WC and BMI as a trait in the FBAT analysis, D11S1304 showed a strong relationship with all situations. It should be noted that these regions harbor the ApoAI gene cluster25. Palmer et al.35 used 59 large pedigrees to identify a locus on chromosome 8q21.3 for the body mass index (BMI) with markers D8S1179 and D8S1128 yielding the highest LOD scores (> 2) under a model-free linkage analysis. One of the studies' limitations is the low number of patients with MetS and without a high WC. These patients are rare per definition, but they exist, and of course, this would have been the best negative control group.

In summary, the obtained results suggest that regions 8q22-24, 11q23-25, and 12q13-15 are very likely to contain genes like VPS13B, APOA5, ZPR1, BUD13, and FAIM2 that control obesity-related factors in Iranian families with MetS21,22,27,28,31,32. A more refined analysis with high-density short tandem repeat (STR) markers in the regions of interest around the marker with the most robust evidence for linkage and association, which possibly focuses on very informative families identified in this study, is needed to pave the way to identify responsible genes.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted within the framework of the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS). The TLGS is a large-scale community-based prospective study performed on a representative sample of residents in district 13 of Tehran36. The subjects were selected from the third examination phase (2006–2008) of the TLGS. All the subjects answered a questionnaire on demographic and biochemical factors and smoking habits at study entry. Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants. The ethics committee approved this study in the Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences. All methods of the study were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Phenotype measurement

The height, weight, WC, and blood pressure of each individual were measured, and BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kilogram) by the square of height (m2). Fasting blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglyceride levels were measured immediately from fresh sera, as described previously37,38. Serum HDL-C levels were measured after the precipitation of ApoB containing lipoproteins with dextran-magnesium sulfate39. LDL-C and VLDL concentrations in samples with serum triglyceride levels < 400 mg/dl were calculated using Friedewald’s equation and one-fifth of triglyceride levels, respectively40. Coefficients of variation (CV) for total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglyceride measurements were below 5%. Waist circumference ≥ 90 cm and a BMI ≥ of 25 kg/m2 were recorded as main phenotypes.

Family selection

Families were selected based on having at least one member affected by MetS. MetS was defined based on the Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III), which was modified locally41. Among them, families with at least two members with WC ≥ 90 cm and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 in a different generation were selected41. Families in this sample were 91 pedigrees, 201 nuclear families, 508 individuals, and three-generation families comprising 295 parents, 273 full siblings, and 11 grandparents.

Marker selection

Regions with high LOD scores (> 3) were selected according to the previous studies, including 8(q22.1-q24.3)15–20, 11(q23.3-q25)23–26, 12(q13.12-q15)18,29,30, and 16(q23.3-q24.3)33. Among them, 12 highly informative STR loci were selected to allow good coverage of the regions: D8S1132, D8S1779, D8S514, D8S1743, D11S1304, D11S1998, D11S934, D12S1632, D12S329, D12S96, D16S3096, and D16S2624.

Genotyping of microsatellite markers

Buffy coats were separated from the non-coagulated blood samples and stored at -70 °C until processing. Genomic DNA was extracted by the Proteinase K, salting out the standard method42. The Gene Amp PCR System 9700 (ABI Co. USA) was used to simultaneously amplify 12 STR loci, including D8S1132, D8S1779, D8S514, D8S1743, D11S1304, D11S1998, D11S934, D12S1632, D12S329, D12S96, D16S3096, and D16S2624. Amplification was performed, as previously described43. The raw data were analyzed using the ABI Data Collection Software and Gene Mapper 3.2 (Applied Biosystems). Laboratory internal control standards were used for quality control.

Statistical analysis

The Cyrillic program drew family pedigrees, and PedCheck44 and Merlin45 checked Mendelian and possible genotyping errors. Markers with incompatible or unlikely genotypes were removed for the concerned individuals. Marker allele frequencies were estimated from the founders of the 91 families38. Marker map positions were based on the sex-average maps from the Marshfield Medical Research Foundation16. The FBAT package was used to test for association in the presence of linkage46. FBAT provided a Chi-square test that examined the composite null hypothesis of no linkage or no linkage disequilibrium, correcting for confounding due to admixture. Merlin software performed multipoint nonparametric linkage analysis45. Merlin outputs were nonparametric NPLall (Z) and LOD scores and their corresponding asymptotic p-values. Corrected p-values based on Bonferroni’s correction (multiplying the uncorrected p-values by the number of alleles) were also reported for association tests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the patients participating in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study.

Author contributions

M.S.D put forward the idea; M.S.D and M.Z. wrote and debug programs; M.S.D, M.Z., and S.M. analyzed the results; and F.A. and M.H. critically reviewed the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.GM, R. J. N. Banting Lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. 1988. 13, 65 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus Alberti, K. G. M. M. & Zimmet, P. Z. J. D. m. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1. Provisional report of a WHO consultation. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daneshpour M, Mehrabi Y, Hedayati M, Houshman M, Azizi F. A multivariate study of metabolic syndrome risk factors, using factor analysis: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. IJEM. 2006;8:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosseinpanah F, Barzin M, Eskandary PS, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Trends of obesity and abdominal obesity in Tehranian adults: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:426. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akrami, S. M. et al. The common-866G/A polymorphism of the UCP2 gene in healthy Iranians compared with world populations. 103–110 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Alavi-Shahri, J. et al. Association between angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene polymorphism and metabolic syndrome in a young female Iranian population. 41, 343–349 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bazzaz J, et al. Apolipoprotein E gene polymorphism and total serum cholesterol level in Iranian population. 2010;56:173. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.68629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meshkani, R. et al. Pro12Ala polymorphism of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ2 (PPARγ-2) gene is associated with greater insulin sensitivity and decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in an Iranian population. 45, 477–482 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Meshkani, R. et al. 1484insG polymorphism of the PTPN1 gene is associated with insulin resistance in an Iranian population. 38, 556–562 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mirzaei, H. et al. Polymorphism of Pro12Ala in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ2 gene in Iranian diabetic and obese subjects. 7, 453–458 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Mohammadzadeh, G., Zarghami, N. J. S. J. o. C. & Investigation, L. Associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the adiponectin gene, serum adiponectin levels and increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Iranian obese individuals. 69, 764–771 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Eshraghi, P., Hedayati, M., Daneshpour, M., Mirmiran, P. & Azizi, F. J. B. j. o. b. s. Association of body mass index and Trp64Arg polymorphism of the β3-adrenoreceptor gene and leptin level in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. 64, 117–120 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Speliotes EK, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locke AE, et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chagnon YC, et al. A genome wide linkage study of obesity as secondary effect of antipsychotics in multigenerational families of eastern Quebec affected by psychoses. Mol. Psychiatry. 2004;9:1067–1074. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chagnon YC, et al. Genomic scan for genes affecting body composition before and after training in Caucasians from HERITAGE. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;90:1777–1787. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Platte P, et al. A study of linkage and association of body mass index in the Old Order Amish. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2003;121C:71–80. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris JM, et al. Quantitative trait loci for abdominal fat and BMI in Hispanic-Americans and African-Americans: The IRAS Family study. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2005;29:67–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong C, Li WD, Li D, Price RA. Interaction between obesity-susceptibility loci in chromosome regions 2p25-p24 and 13q13-q21. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;13:102–108. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong C, et al. Possible genomic imprinting of three human obesity-related genetic loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:427–437. doi: 10.1086/428438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao VRBV, Candasamy M, Bhattamisra SK. Obesity an overview: Genetic conditions and recent developments in therapeutic interventions. Diab. Metab. Syndrome Clin. Res. Rev. 2019;13:2112–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alipour N, et al. Mutations in the VPS13B gene in Iranian patients with different phenotypes of Cohen syndrome. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020;70:21–25. doi: 10.1007/s12031-019-01394-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsay RS, Kobes S, Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hanson RL. Genome-wide linkage analysis assessing parent-of-origin effects in the inheritance of type 2 diabetes and BMI in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 2001;50:2850–2857. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arya R, et al. Evidence of a novel quantitative-trait locus for obesity on chromosome 4p in Mexican Americans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:272–282. doi: 10.1086/381717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone S, et al. A major predisposition locus for severe obesity, at 4p15-p14. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1459–1468. doi: 10.1086/340670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moslehi, R., Goldstein, A. M., Beerman, M., Goldin, L. & Bergen, A. W. A genome-wide linkage scan for body mass index on Framingham Heart Study families. BMC Genet.4(Suppl 1), S97 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Oh S-W, et al. Genome-wide association study of metabolic syndrome in Korean populations. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0227357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohde K, et al. Genetics and epigenetics in obesity. Metabolism. 2019;92:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collaku A, et al. A genome-wide linkage scan for dietary energy and nutrient intakes: the health, risk factors, exercise training, and genetics (HERITAGE) family study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79:881–886. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng HW, et al. A genome-wide linkage scan for quantitative-trait loci for obesity phenotypes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1138–1151. doi: 10.1086/339934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hachim MY, et al. An integrative phenotype-genotype approach using phenotypic characteristics from the UAE National Diabetes study identifies HSD17B12 as a candidate gene for obesity and type 2 diabetes. Genes. 2020;11:461. doi: 10.3390/genes11040461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herrera BM, Keildson S, Lindgren CM. Genetics and epigenetics of obesity. Maturitas. 2011;69:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X, et al. A genome scan among Nigerians linking resting energy expenditure to chromosome 16. Obes. Res. 2004;12:577–581. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada, Y. et al. Identification of rs7350481 at chromosome 11q23.3 as a novel susceptibility locus for metabolic syndrome in Japanese individuals by an exome-wide association study. Oncotarget8, 39296–39308 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Palmer LJ, et al. Whole genome scan for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity in African-American families. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004;169:1314–1321. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-493OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rationale and Design Azizi F, Rahmani M, Emami H & M., M. Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. CVD Prev. 2000;3:242–247. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azizi F, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly: the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. J. Cardiovasc. Risk. 2003;10:65–73. doi: 10.1097/00043798-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daneshpour MS, et al. Allele frequency distribution data for D8S1132, D8S1779, D8S514, and D8S1743 in four ethnic groups in relation to metabolic syndrome: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Biochem. Genet. 2009;47:680–687. doi: 10.1007/s10528-009-9265-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin. Chem. 1982;28:1379–1388. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/28.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972;18:499–502. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azizi F, et al. Appropriate waist circumference cut-off points among Iranian adults: the first report of the Iranian National Committee of Obesity. Arch. Iran Med. 2010;13:243–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truett, G. E. et al. Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT). Biotechniques29, 52–54 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Daneshpour, M. et al. Allele frequency distribution for D11S1304, D11S1998 and D11S934 and metabolic syndrome in TLGS. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol.In press (2010).

- 44.O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin–rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet. Epidemiol. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S36–42. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]